REPORT OF THE COMMISSION TO LOCATE THE SITE OF THE FRONTIER FORTS OF PENNSYLVANIA.

VOLUME TWO.

CLARENCE M. BUSCH.

STATE PRINTER OF PENNSYLVANIA.

1896.

THE FRONTIER FORTS OF WESTERN PENNSYLVANIA.

Pages 509-536.

BATTLE OF BUSHY RUN.

The battle of Bushy run which ended Pontiac's War, relieved the posts of Fort Pitt and Ligonier, saved the western frontier of the Province, and brought the savages to submission, was peculiarly, one of the most remarkable engagements ever fought between the two races. Its importance in explaining the history of these frontiers is such that an account of it could not well be omitted, where mention is made of the forts and posts of the western part of the Province.

The account here presented has been largely taken from Mr. Francis Parkman's version of that campaign. Mr. Parkman himself followed, often literally, but usually with amplification, the Historical Account of Col. Bouquet's Expedition by Thomas Hutchins, Geographer to The United States, with an introduction by Dr. Wm. Smith, provost of the College of Philadelphia, as well as the letters of Col. Bouquet to Gen. Amherst, which are attached hereto. To this source of authority Mr. Parkman had access to much new material, supplied especially from the correspondence of the officers who served in Pontiac's war and from the Bouquet and Haldimand Papers, belonging to the manuscript collections of the British Museum. In addition to these, the Historical Collections of Pennsylvania, The Olden Time and the Pennsylvania State Archives and Records were by him consulted and drawn upon.

From these sources, following Mr. Parkman and wherever necessary, the introduction to the Historical Account, almost literally, avoiding, as far as it is consistent, irrelevant matter, and occasionally adding references for purposes of explanation from authoritative records, has this account been made up. Feeling justified in its insertion here as a part of the Report which treats of such posts as Fort Pitt and Fort Ligonier and other important posts, it is here submitted as a part of the same.

It is proper to add that the editor and compiler has diligently verified all the references available as to the statements of fact. The topography and the observations on the condition of the expedition as it progressed westward, as they are expressed in the language of Mr. Parkman, are so true to nature in the first instance and so consonant with probability, inference and reason in the other, that they could not well lie altered with advantage.

The whole text, in the opinion of the editor, is, therefore, as near a correct account as can probably be made up from the documents available.

There are added also the letters of Col. Bouquet to Gen. Amherst, which indeed are his official report of the battle. Of these Mr. Parkman says: "The dispatches written by Col. Bouquet, immediately after the two battles near Bushy run, contain so full and clear an account of those engagements, that the collateral authorities consulted have served rather to decorate and enliven the narrative than to add to it any important facts. The first of these letters was written by Bouquet under the apprehension that he should not survive the expected conflict of the next day. Both were forwarded to the commander-in-chief by the same express, within a few days after the victory."

Mr. Parkman's account, referred to above, is contained in the Conspiracy of Pontiac; the Historical Account of the Expedition against the Ohio Indians in 1764, etc., is in the Olden Time, Vol. i, 203, but there has been a reprint and it is contained in the Bibliotheca Americana, 1893, (Robert Clark & Co., Cin., O.).

The general peace, concluded between Great Britain, France and Spain, 1762, was universally considered a most happy event in America. A danger, however, arose unexpectedly from a quarter in which our people imagined themselves in the most perfect security; and just at the time when it was thought the Indians were entirely awed and almost subjected to our power, they suddenly fell upon the frontiers of our most valuable settlements, and upon all our outlying forts, with such unanimity in the design, and with such savage fury in the attack, as had not been experienced in any former war.

The Shawanese, Delawares and other Ohio tribes took the lead in this war, and seemed to have begun it rather precipitately before the other tribes in confederacy with them were ready for action.

Their scheme appears to have been projected with much deliberate mischief in the intention, and more than unusual skill in the system of execution. They were to make one general and sudden attack upon our frontier settlements in the time of harvest, to destroy our men, corn, cattle, and soforth, as far as they could penetrate, and to starve our outposts by cutting off their supplies, and all communication with the inhabitants of the provinces.

In pursuance of this bold and bloody project, they fell suddenly upon our traders whom they had invited into their country, murdered many of them, and made one general plunder of their effects, to an immense value.

The frontiers of Pennsylvania, Maryland and Virginia were immediately overrun with scalping parties, making their way with blood and devastation wherever they came, and those examples of savage cruelty, which never fail to accompany an Indian war.

All our out-forts, even at the remotest distances, were attacked about the same time, and the following ones soon fell into the enemy's hands, viz: LeBoeuf, Venango, Presqu' isle, on and near Lake Erie; La Bay, upon Lake Michigan; St. Joseph's, upon the river of that name; Miamas, upon the Miamas river; Ouachtanon upon the Ouabache, (Wabash); Sandusky, upon Lake Junundat; Michilimachinac, (Mackinaw.)

Being but weakly garrisoned, trusting to the security of a general peace so lately established, unable to obtain the least intelligence from the colonies, or from each other, and being separately persuaded by their treacherous and savage assailants that they had carried every other place before them, it could not be expected that these small posts could hold out long; and the fate of their garrisons is terrible to relate.

The news of the surrender, and the continued ravages of the enemy struck all America with consternation, and depopulated a great part of our frontiers. We now saw most of those posts suddenly wrested from us which had been the great object of the late war, and one of the principal advantages acquired by the peace. Only the forts of Niagara, Detroit, and Fort Pitt, remained in our hands, of all that had been purchased with so much blood and treasure. But these were places of consequence, and it is remarkable that they alone continued to awe the whole power of the Indians, and balance the fate of the war between them and us.

These forts, being larger, were better garrisoned and supplied to stand a siege of some length, than the places that fell, Niagara was not attacked, the enemy judging it too strong.

The officers who commanded the other two deserved the highest honor for the firmness with which they defended them, and the hardships they sustained rather than deliver up places of such importance. Major Gladwin in particular, who commanded at Detroit, had to withstand the united and vigorous attacks of all the nations living upon the lakes. The design of this article, however, leads us more immediately to speak of the defense and relief of Fort Pitt by that remarkable campaign.

The Indians had early surrounded that place, and cut off all communication from it, even by message. Though they had no cannon, nor understood the methods of a regular siege yet, with incredible boldness, they posted themselves under the banks of both rivers by the walls of the fort, and continued as it were buried there from day to day, with astonishing patience; pouring in an incessant storm of musketry and fire arrows; hoping at length, by famine, by fire, by harassing out the garrison, to carry their point.

Captain Ecuyer, who commanded there, though he wanted several necessaries for sustaining a siege, and though the fortifications had been greatly damaged by the floods, took all the precautions which art and judgment could suggest for the repair of the place, and repulsing the enemy. His garrison, joined by the inhabitants, and surviving traders who had taken refuge there, seconded his efforts with resolution. Their situation was alarming, being remote from immediate assistance, and having to deal with an enemy from whom they had no mercy to expect.

Gen. Amherst, the Commander-in-Chief, not being able to provide in time for the safety of the remote posts, bent his chief attention to the relief of Detroit, Niagara and Fort Pitt. The communication with the two former was chiefly by water, from the colony of New York, and it was on that account the more easy to throw succors into them.

When this war burst upon the country it was at a time when the colonies were greatly exhausted, and when the Commander-in-Chief of the English forces on the American establishment, was almost bereft of resources. The armies which conquered Canada had been disbanded or sent home; nothing remained but a few fragments or skeletons of regiments lately arrived from the West Indies, enfeebled by disease and by hard service. In one particular, however, he had reason to congratulate himself-the character of the officer who commanded under his orders in Pennsylvania, Virginia, and Maryland. Colonel Henry Bouquet was a Swiss, of the Canton of Berne, who had followed the trade of war from boyhood. He had served first the king of Sardinia, and afterward the republic of Holland; and when the French war began in 1755, he accepted the commission of lieutenant-colonel, in a regiment newly organized, under the direction of the Duke of Cumberland, expressly for American service. The commissions were to be given to foreigners as well as to Englishmen and provincials; and the rank were to be filled chiefly from the German emigrants in Pennsylvania and other provinces. The men and officers of this regiment, known as the "Royal Americans" had now, for more than six years, been engaged in the rough ad lonely service of the frontiers and forests; and when the Indian war broke out, it was chiefly they, who, like military hermits, held the detached outposts of the West.

Bouquet, however, who was at this time Colonel of the first battalion, had his headquarters at Philadelphia, where he was held in great esteem. His person was fine, and his bearing composed and dignified; perhaps somewhat austere, for he is said to have been more respected than loved by his officers. Nevertheless, their letters are very far from indicating any want of cordial relations. He was fond of the society of men of science, and wrote English better than most British officers of the time. Here and there, however, a passage in his letters suggest the inference, that the character of the gallant mercenary was toned by his profession, and to the unideal epoch in which he lived. Yet he was not the less an excellent soldier; indefatigable, faithful, full of resource, and without those arrogant prejudices which impaired the efficiency of many good British officers, in the recent war, and of which Sir Jeffrey Amherst was a conspicuous example. He had acquired a practical knowledge of Indian warfare, and it is said that, in the course of the hazardous partisan service in which he was often engaged when it was necessary to penetrate dark defiles and narrow passes, he was sometimes known to advance before his men, armed with a rifle, and acting the part of a scout.

Sir Jeffrey Amherst, from whom all orders came had flattered himself that the Indian uprising was of little moment, and that the alarm would end in nothing but a rash attempt of what the Senecas had been threatening for some time past. He declared that while defenceless families, or small posts, might be cut off, yet "the post of Fort Pitt, or any of the others commanded by officers, could certainly never be in danger from such a wretched enemy." He, however, in the same letter to Colonel Bouquet in which he so expresses his opinion, says that he only wanted to hear what further steps the savages had taken, when he would put into execution the measures which he had taken for operations against them.

But the news which came to Colonel Bouquet from Ecuyer at Fort Pitt grew worse and worse. The letters which contained these reports were forwarded to Amherst who wrote to Bouquet on receiving the latest that although it was extremely inconvenient at the time, yet that he would not defer sending a reinforcement to keep up the communication between Philadelphia and the out-posts. Accordingly he ordered two companies of the Forty-second and Seventy-seventh regiments to join Bouquet at Philadelphia, and directed him, if he thought it necessary, to himself proceed to Fort Pitt, so that he might be better enabled to put in execution the requisite orders for receiving the communication and reducing the Indians to reason.

The tidings from the outposts becoming worse and worse, Amherst rearranged such troops as he had for active service. His plan was to push forward as many troops as possible to Niagara by way of Oswego, and to Presqu' Isle by way of Fort Pitt, and thence to send them up the lakes to take vengeance on the offending tribes.

But Bouquet, with superior discernment, recognizing the peril of the small outlying posts like Venango and Le Boeuf, proposed to abandon them, and concentrate at Fort Pitt and Presqu' Isle; a movement which, could it have been executed in time, would have saved both blood and trouble. But Amherst would not consent to give these posts up.

Bouquet then began to take active steps for the relief of the western posts, with the two companies of troops which he had at his command. It being apparent, however, that these were insufficient, Amherst ordered the remains of the Forty-second and the Seventy-seventh--the first consisting of two hundred and fourteen men including officers, and the latter of one hundred and thirty-three, officers included-to march (June 23d, 1763) under the command of Major Campbell of the Forty-second, to Bouquet. Two days after that, Amherst writes to Bouquet: "All the troops from hence that could be collected are sent you; so that should the whole race of Indians take arms against us I can do no more."

Bouquet was now busy on the frontier in preparations for pushing forward to Fort Pitt with the troops sent him. After reaching the fort, with his wagon-trains of ammunition and supplies, he was to proceed to Venango and Le Boeuf, reinforce and provision them; and then advance to Presqu' Isle to await Amherst's orders. He was encamped near Carlisle when, on the 3d of July, he heard, by express-rider sent out by Captain Ourry from Bedford, of the loss of Presqu' Isle, Le-Boeuf, and Venango. He at once sent the news to Amherst.

Early orders had been given to prepare a convoy of provisions on the frontiers of Pennsylvania, but such were the universal terror and consternation of the inhabitants, that when Colonel Bouquet arrived at Carlisle, nothing had yet been done. A great number of the plantations had been plundered and burnt by the savages; many of the mills destroyed, and the fall-ripe crops stood waving in the field, ready for the sickle, but the reapers were not to be found. The greatest part of the county of Cumberland, through which the army had to pass, was deserted, and the roads were covered with distressed families flying from their settlement, and destitute of all the necessaries of life.

When he arrived at Carlisle, at the end of June, he found every building in the fort, every house, barn, and hovel, in the little town, crowded with the families of settlers, driven from their homes by the terror of the tomahawk. He heard one ceaseless wail of moaning and lamentation, from widowed wives and orphaned children.

Bouquet was full of anxieties for the safety of Fort Bedford and Fort Ligonier. Captain Lewis Ourry commanded at Bedford and Lieutenant Archibald Blane, at Ligonier. These kept up a precarious correspondence with him and each other, and with Captain Ecuyer at Fort Pitt, by means of express-riders, a service dangerous to the last degree, and which soon became impracticable.

It was of the utmost importance to hold these posts, which contained stores and munitions, the capture of which by the Indians would have led to the worst consequences. Ourry had no garrison worth the name; but at every Indian alarm the scared inhabitants would desert their farms, and gather for shelter around his fort, to disperse again when the alarm was over.

On the 3d of June, he writes to Bouquet: "No less than ninety-three families are now in here for refuge, and more hourly arriving. I expect ten more before night." He adds that he had formed the men into two militia companies: "My returns," he pursues, "amount already to one hundred and fifty-five men. My regulars are increased by expresses, etc., to three corporals and nine privates; no despicable garrison!"

On the 7th, he sent another letter. * * * * "As to myself, I find I can bear a good deal. Since the alarm I never lie down till about 12, and am walking about the fort between 2 and 3 in the morning, turning out the guards and sending out patrols, before I suffer the gates to remain open. * * * * My greatest difficulty is to keep my militia from straggling by two and threes to their dear plantations, thereby exposing themselves to be scalped and weakening my garrison by such numbers absenting themselves. They are still in good spirits, but they don't know all the bad news. I shall use all means to prevail on them to stay till some troops come up. I long to see my Indian scouts come in with intelligence; but I long more to hear the Grenadier's March, and see some more redcoats."

Ten days later, he writes. * * * * "I am now, as I foresaw, entirely deserted by the country people. No accident having happened here, they have gradually left me to return to their plantations; so that my whole force is reduced to twelve Royal Americans to guard the fort, and seven Indian prisoners. I should be very glad to see some troops come to my assistance. A fort with 5 bastions cannot be guarded, much less defended, by a dozen men; but I hope God will protect us."

On the next day, he writes again: "This moment I return from the parade. Some scalps taken up Dunning's creek yesterday, and to-day some families murdered and houses burnt, have destroyed me of my militia. * * * * Two or three other families are missing, and the houses are seen in flames. The people are all flocking in again."

Two days afterwards, he says that, while the countrymen were at drill on the parade, 3 Indians attempted to seize two little girls close to the fort, but were driven off by a volley. "This," he pursues, "Has added greatly to the panic of the people, with difficulty I can restrain them from murdering the Indian prisoners." And he concludes: "I can't help think that the enemy will collect, after cutting off the little posts one after another, leaving Fort Pitt as too tough a morsel, and bend their whole force upon the frontiers."

On the 2d of July, he describes an attack of about 20 Indians on a party of mowers, several of whom were killed. "This accident," he says, "has thrown the people into a great consternation, but such is their stupidity that they will do nothing right for their own preservation."

Such was the condition of affairs at Fort Bedford. On the I next day, the 3d of July, Captain Ourry from there sent a mounted soldier to Bouquet with the news of the loss of Presqu' Isle and its sister posts, which Lieutenant Archibald Blane, who, having received the news from Fort Pitt contrived to send him; though he himself in his feeble little fort of Ligonier, buried in a sea of forests hardly dared hope to maintain himself.

Some account is given of what Lieutenant Blane and his little garrison had to endure, and of their fortitude and undaunted courage during this time, where we speak of Fort Ligonier.

Bouquet, encamped at Carlisle, was still urging on his preparations, but was met by obstacles at every step. The Province did little, and the people, partly from the apathy and confusion of terror, could not be brought to operate with the regulars. In such despondency of mind it is not surprising, that though their whole was at stake, and depended entirely upon the fate of this little army, none of them offered to assist in the defense of the country, by joining the expedition in which they would have been of infinite service, being in general well acquainted with the woods, and excellent marksmen.

While vexed and exasperated, Bouquet labored at his thankless task, remonstrated with provincial officials, or appealed to refractory farmers, the terror of the country people increased every day When on Sunday, the 3d of July, (1763), Ourry's express rode into Carlisle with the disastrous news from Presqu' Isle and the other outposts, he stopped for a moment on the village street to water his horse. A crowd of countrymen were instantly about him, besieging him with questions. He told his ill-omened story; and added as, remounting, he rode towards Bouquet's tent, "The Indians will be here soon." All was now excitement and consternation. Messengers hastened out to spread the tidings; and every road and pathway leading into Carlisle was beset with the flying settlers, flocking thither for refuge. Some rumors were heard that the Indians were come. Fugitives had seen the smoke of burning cabins in the valleys. A party of the inhabitants armed themselves and went out to warn the living, and bury the dead. Their worst fears were realized. They saw everywhere the frightful evidence of the presence of the savages, who were all around them.

The surrounding country was by this time completely abandoned by the settlers. Many sought refuge at Carlisle; some continued their flight to Lancaster, and some did not stop till they reached Philadelphia. Every place about Carlisle was full, and a multitude of the refugees, unable to find shelter in the town, had encamped in the woods and on the adjacent fields, erecting huts of branches and bark, and living on such charity as the slender means of the towns-people could supply. Passing among them one would have witnessed every form of human misery. In these wretched encampments were men, women and children, bereft at one stroke of friends, of home, and the means of supporting life. Some stood aghast and bewildered at the sudden and fatal blow; others were sunk in the apathy of despair; others were weeping and moaning with irrepressible anguish. With not a few, the craven passion of fear drowned all other emotion, and day and night they were haunted with visions of the bloody knife and the reeking scalp, while in others, every faculty was absorbed by the burning thirst for vengeance, and mortal hatred against the whole Indian race.

The commander found that, instead of expecting such supplies from a miserable people, he himself was called by the voice of humanity to bestow on them some share of his own provisions. In the midst of the general confusion, the supplies necessary for the expedition became very precarious, nor was it less difficult to procure horses and carriages for the use of the troops. However, in eighteen days after his arrival at Carlisle, by the prudent and active measures which he pursued, joined to his knowledge of the country, and the diligence of the persons he employed, the convoy and carriages were procured with the assistance of the interior parts of the country, and the army proceeded.

At length the army, such as it was, being gathered around him, and the convoy ready, Bouquet broke up his camp and began his march. The force under his command did not exceed 500 men, of whom the most effective were the Highlanders of the Forty-second regiment. The remnant of the Seventy-seventh, which was also with him, was so enfeebled by the West Indian exposures, that Amherst had at first pronounced it fit only for garrison duty, and nothing but necessity had induced him to employ it on this arduous service. As the heavy wagons of the convoy lumbered along the streets of Carlisle, guarded by the bare-legged Highlanders, in kilts and plaids, the crowd gazed in anxious silence, for they knew that their all was at stake on the issue of this dubious enterprise. There was little to reassure them in the thin frames and haggard looks of the worn-out veterans still less in the sight of sixty invalid soldiers, who, unable to walk, were carried in wagons, to furnish a feeble reinforcement to the small garrisons along the route. The desponding rustics watched the last gleam of the bayonets, the last flutter of the tartans, as the rear files vanished in the woods; then returned to their hovels, prepared for tidings of defeat, and ready, when they heard them, to abandon the country, and fly beyond the Susquehanna.

The undertaking was enough to appall the stoutest of hearts. Before him a distance of 200 miles over mountains and through the gloomy wilderness, lay the point of his destination. The tidings and reports which he had heard, the places cut off, the uncertainty whether these places could hold out, the condition of those around him, and the lack of assistance rendered him–these things were enough to intimidate the stoutest of men. In that dark wilderness lay the bones of Braddock and the hundreds that perished with him. The number of the slain on that bloody day exceeded Bouquet's whole force; while the strength of the assailants was inferior to that of the swarms who now infested the forests. Bouquet's troops were, for the most part, as little accustomed to the back-woods as those of Braddock; but their commander had served seven years in America, and perfectly understood his work. He had attempted to get frontiersmen to act as scouts, but they would not leave their families whom they remained to defend. He had therefore to employ his Highlanders as flankers, in order to protect his line of march and prevent surprise; but these proved to be unfit for that service, as they invariably lost themselves in the woods.

His immediate concern was for Fort Ligonier. He knew that the loss of the post would be most disastrous to his army and to the entire Province, and that nothing could possibly save Fort Pitt. It had already been attacked, but had held out. He determined to risk sending a small detachment to its relief. Thirty Highlanders were chosen, who, furnished with guides, were ordered to push forward with the utmost speed, avoiding the road, traveling by night, on unfrequented paths, and lying close by day. They reached Bedford in due time. Captain Ourry from here, prior to this had sent a party of 20 backwoodsmen to reinforce Lieutenant Blane, knowing the straits into which he had fallen. The Highlanders on coming to Bedford, rested there several days–Ourry expecting an attack during that time–and then again set out. Coming near to Ligonier, they found the place beset by the Indians; but they made themselves known and under a running fire entered into the fort.

At Shippensburg, on the eastern base of the Alleghenies, something more than twenty miles from Carlisle, was gathered a starving, frightened and stricken multitude. According to report there were there on the 25th of July, 1763, of the distressed back inhabitants, namely, men 301; women 345; and children, 738; many of whom were obliged to lie in barns, stables, cellars, and under old leaky sheds, the dwelling-houses being all crowded.

Two companies of light infantry had been sent forward from the main body to succor Bedford. Captain Ourry had taken all necessary precautions to prevent a surprise, and repel open force, as also to render ineffectual the enemy's fire arrows. He armed all the fighting men, who formed two companies of volunteers, and did duty with the garrison till the arrival of the two companies which had been detached from the little army.

The army advancing reached Fort Loudoun, on he declivity of Cove mountain, and climbed the wood-encumbered defiles beyond. On their right stretched far off the green ridges of the Tuscarora; in front, mountains beyond mountains were piled up against the sky. Over rocky heights and through deep valleys, they reached at length Fort Littleton, a provincial post, in which, with incredible perversity the government of Pennsylvania had refused to place a garrison. Not far distant was the feeble post of the Juniata, empty like the other; for the two or three men who held it had been withdrawn by Ourry. On the 25th of July, they reached Bedford, hemmed in by encircling mountains. It was the frontier village and the center of a scattered border population, the whole of which was now clustered in terror in and around the fort; for the neighboring woods were full of prowling savages. Ourry reported that for several weeks nothing had been heard from the westward, every messenger having been killed and the communication completely cut off.

At Bedford, Bouquet, fortunately secured thirty backwoodsmen to accompany him. He remained three days in his camp here to rest his men and animals. Then, leaving his invalids, to garrison the fort, he struck out into the wilderness of woods. They followed the narrow road which had been made by Forbes–a rugged track up and down steep hillsides, across swamps, through thickets, under the gloomy boughs of the over-arched trees where the heavy foliage shut out the sun. He was vigilant in guarding against surprise. Riflemen from the frontier scoured the woods in front and on the flanks. A party of backwoodsmen led the way; these were followed closely by the pioneers, the pack-horses, the wagons drawn by oxen, and the cattle were in the center, guarded by the regulars. A rear guard of backwoodsmen closed the line of march. Slowly and with great toil, man and beast suffering much from the stifling heat of the pent-up forest, the train wound its zigzag way up the Alleghenies. From these mountains the country was less rugged, but their way was beset with dangers constantly increasing. On the 2d of August they reached Fort Ligonier, about 150 miles from Carlisle, and nearly midway between Fort Bedford and Fort Pitt. The Indians who were about the place vanished at their approach. Their absence and the secrecy of their movements was an ominous thing. The garrison having been completely blockaded for several weeks, could give no information as to the savages. They had heard nothing from the outside world during the trying weeks they were hemmed in. To Bouquet in this uncertainty, it was a trying time. This want of intelligence, he has stated "is often a very embarrassing circumstance in the conduct of a campaign in America." He well knew, moreover, that the Indians were watching every movement his army made although they themselves were not detected. He therefore determined to leave his oxen and wagons at Fort Ligonier, and to proceed only with his packhorses and some cattle.

It is a circumstance not to be forgotten, that Bouquet had opened this road from Bedford to Fort Pitt, as the leader of the advance of Forbes' army; and that under him were constructed the first works at Ligonier. His personal knowledge was doubtless a great factor in his campaign.

On the 4th of August, the army thus relieved, resumed its march, taking with it 350 packhorses upon which were loaded the flour and supplies, and a few cattle. The heavy artillery, the wagons and oxen, the knapsacks and all needless war material were left at Fort Ligonier. The men reserved only their blankets and light arms. The first night they encamped at no great distance from Ligonier, for he had so timed his march as to reach by the next day a desirable place on the route called Bushy run, or as it was known then, Byerly's Station. He proposed to reach this place early the next day.

On the morning of the fifth, the tents were struck at an early hour, and the troops began their march through a country broken with hills and deep hollows, covered with the tall, dense forest, which spread for countless leagues around. By one o'clock they had advanced seventeen miles; and the guides assured them that they were within half a mile of Bushy run, their proposed resting place. The tired soldiers were pressing forward with renewed alacrity, when suddenly the report of rifles from the front sent a thrill along the ranks; and, as they listened, the firing thickened into a fierce, sharp rattle; while shouts and whoops, deadened by the intervening forest, showed that the advance guard was hotly engaged. The two foremost companies were at once ordered forward to support it; but, far from abating, the fire grew so rapid and furious as to argue the presence of an enemy at once numerous and resolute. At this the convoy was halted, the troops formed into a line and a general charge ordered. Bearing down through the forest with fixed bayonets, they drove the yelping assailants before them, and swept the ground clear. But at the very moment of success, a fresh burst of whoops and firing was heard from either flank; while a confused noise from the rear showed that the convoy was attacked. It was necessary instantly to fall back for its support. Driving off the assailants, the troops formed in a circle around the crowded and terrified horses. Though they were new to the work, and though the numbers and movements of the enemy, whose yelling on every side, were concealed by the thick forest, yet no man lost his composure; and all displayed a steadiness which nothing but implicit confidence in their commander could have inspired. And now ensued a combat of a nature most harassing and discouraging. Again and again, now on this side and now on that, a crowd of Indians rushed up, pouring in a heavy fire, and striving, with furious outcries, to break into the circle. A well-directed volley met them, followed by a steady charge of the bayonet. They never waited an instant to receive the attack, but, leaping backwards from tree to tree, soon vanished from sight, only to renew their attack with unabated ferocity in another quarter. Such was their activity, that very few of them were hurt; while the British, less expert in bush-fighting suffered severely. Thus the fight went on, without intermission, for seven hours, until the forest grew dark with approaching night. Upon this the Indians gradually slackened their fire, and the exhausted soldiers found time to rest.

It was impossible to change their ground in the enemy's presence, and the troops were obliged to encamp upon the hill where the combat had taken place, though not a drop of water was to be found there. Fearing a night attack, Bouquet stationed numerous sentinels and outposts to guard against it; while the men lay down upon their arms, preserving the order they had maintained during the fight. Having completed the necessary arrangements, Bouquet, doubtful of surviving the battle of the morrow, wrote to Sir Jeffrey Amherst, in a few clear, concise words, an account of the day's events. His letter concludes as follows: "Whatever our fate may be, I thought it necessary to give your Excellency this early information, that you may at all events, take such measures as you will think proper with the provinces, for their own safety, and the effectual relief of Fort Pitt; as, in case of another engagement, I fear insurmountable difficulties in protecting and transporting our provisions, being already so much weakened by the losses of this day, in men and horses, besides the additional necessity of carrying the wounded, whose situation is truly deplorable."

The condition of these unhappy men might well awaken sympathy. About sixty soldiers, besides several officers, had been killed or disabled. A space in the centre of the camp was prepared for the reception of the wounded, and surrounded by a wall of flourbags from the convoy, affording some protection against the bullets which flew from all sides during the fight. Here they lay upon the ground, enduring agonies of thirst, and waiting, passive and helpless, the issue of the battle. Deprived of the animating thought that their lives and safety depended on their own exertions; surrounded by a wilderness, and by scenes to the horror of which no degree of familiarity could render the imagination callous, they must have endured mental sufferings, compared to which the pain of their wounds was slight. In the probable event of defeat, a fate inexpressibly horrible awaited them; while even victory would not ensure their safety, since any great increase in their numbers would render it impossible for their comrades to transport them. Nor was the condition of those who had hitherto escaped an enviable one. Though they were about equal in number to their assailants, yet the dexterity and alertness of the Indians, joined to the nature of the country, gave all the advantages of a great superior force. The enemy were, moreover, exulting in the fullest confidence of success; for it was in these very forests that, eight years before, they had nearly destroyed twice their number of the best British troops. Throughout the earlier part of the night, they kept up a dropping fire upon the camp; while, at short intervals, a wild whoop from the thick surrounding gloom told with what eagerness they waited to glut their vengeance on the morrow. The camp remained in darkness, for it would have been dangerous to build fires within its precincts, to direct the aim of the lurking marksmen. Surrounded by such terror, the men snatched a disturbed and broken sleep, recruiting their exhausted strength for the renewed struggle of the morrow.

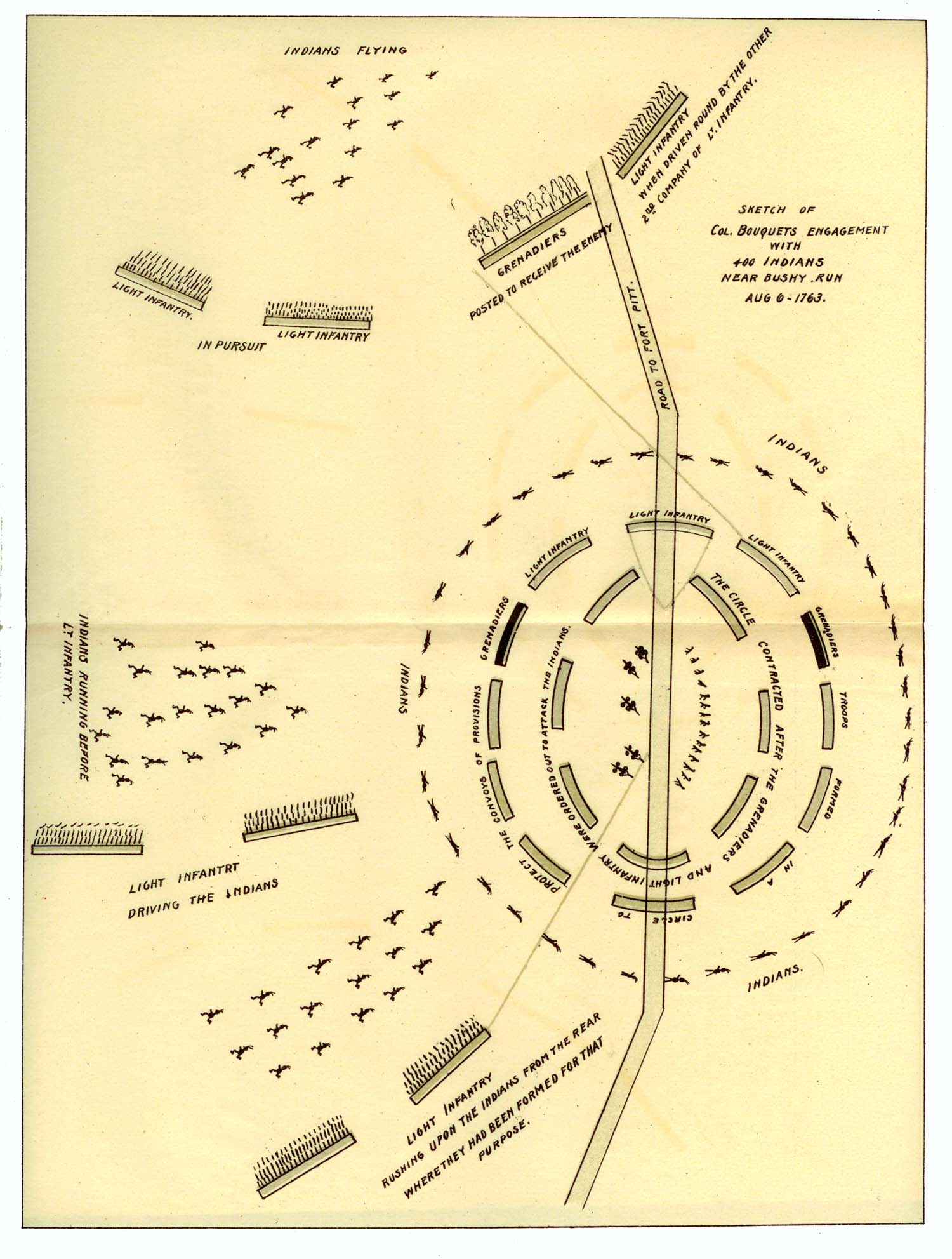

Sketch of Col. Bouquet's Engagement with 400 Indians Near Bushy Run, Aug. 6, 1763.

With the earliest dawn of day, and while the damp, cool forest was still involved in twilight, there arose around the camp a general burst of those horrible cries, which form the ordinary prelude of an Indian battle. Instantly, from every side at once, the enemy opened their fire, approaching under cover of the trees and bushes, and levelling with a close and deadly aim. Often, as on the previous day, they would rush up with furious impetuosity, striving to break into the ring of troops. They were repulsed at every point; but the British, though constantly victorious, were beset with undiminished perils, while the violence of the enemy seemed at every moment on the increase. True to their favorite tactics they would never stand their ground when attacked, but vanish at the first gleam of a levelled bayonet, only to appear again the moment the danger was past. The troops, fatigued by the long march and equally long battle of the previous day, were maddened by the torments of thirst, "more intolerable," says their commander, "than the enemy's fire." They were fully conscious of the peril in which they stood, of wasting away by slow degrees beneath the shot of assailants at once so daring: so cautious, and so active, and upon whom it was impossible to inflict any decisive injury. The Indians saw their distress and pressed them closer and closer, redoubling their yells and howlings; while some of them, sheltered behind trees, assailed the troops in bad English, with abuse and derision.

Meanwhile the interior of the camp was a scene of confusion. The horses, secured in a crowd near the wall of flour-bags which covered the wounded, were often struck by the bullets, and wrought to the height of terror by the mingled din of whoops, shrieks, and firing. They would break away by half scores at a time, burst through the ring of troops and the outer circle of assailants, and scour madly up and down the hillsides; while many of the drivers overcome by the terrors of a scene in which they could bear no active part, hid themselves among the bushes and could neither hear nor obey orders.

It was now about ten o'clock. Oppressed with heat, fatigue, and thirst, the distressed troops still maintained a weary and wavering defence, encircling the convoy in a yet unbroken ring. They were fast falling in their ranks, and the strength and spirits of the survivors had begun to flag. If the fortunes of the day were to be retrieved, the effort must be made at once; and happily the mind of the commander was equal to the emergency. In the midst of confusion he conceived a masterly stratagem. Could the Indians be brought together in a body, and made to stand their ground when attacked, there could be little doubt of the result; and, to effect this object, Bouquet determined to increase their confidence, which had already mounted to an audacious pitch. The companies of infantry, forming a part of the ring which had been exposed to the hottest fire, were ordered to fall back into the interior of the camp; while the troops on either hand joined their files across the vacant space, as if to cover the retreat of their comrades. These orders, given at a favorable moment, were executed with great promptness. The thin line of troops who took possession of the deserted part of the circle were, from their small numbers, brought closer in towards the centre. The Indians mistook these movements for a retreat. Confident that their time was come, they leaped up on all sides, from behind the trees and bushes, and with infernal screeches, rushed headlong towards the spot, pouring in a heavy and galling fire. The shock was too violent to be long endured. The men struggled to maintain their posts; but the Indians seemed on the point of breaking into the heart of the camp, when the aspect of affairs was suddenly reversed. The two companies, who had apparently abandoned their position, were in fact destined to begin the attack; and now they sallied out from the circle at a point where a depression in the ground, joined to the thick growth of trees, concealed them from the eyes of the Indians. Making a short detour through the woods, they came round upon the flank of the furious assailants, and, fired a close volley into the midst of the crowd. Numbers were seen to fall; yet though completely surprised, and utterly at a loss to understand the nature of the attack, the Indians faced about with the greatest intrepidity, and returned the fire. But the Highlanders, with yells as wild as their own, fell on them with the bayonet. The shock was irresistible, and they fled before the charging ranks in a tumultuous throng. Orders had been given to two other companies, occupying a contiguous part of the circle, to support the attack whenever a favorable moment should occur; and they had therefore advanced a little from their position, and lay close crouched in ambush. The fugitives, pressed by the Highland bayonets, passed directly across their front; upon which they rose and poured among them a second volley, no less destructive than the first. This completed the rout. The four companies, uniting, drove the flying savages through the woods, giving them no time to rally or reload their empty rifles, killing many, and scattering the rest in hopeless confusion.

While this took place at one part of the circle, the troops and the savages had still maintained their respective positions at the other; but when the latter perceived the total rout of their comrades, and saw the troops advancing to assail them, they also lost heart, and fled. This discordant outcries which had so long deafened the ears of the English soon ceased altogether, and not a living Indian remained near the spot. About sixty corpses lay scattered over the ground. Among them, were found several prominent chiefs, while the blood which stained the leaves and bushes showed that numbers had fled wounded from the field. The soldiers took but one prisoner, whom they shot to death like a captive wolf. The loss of the British in the two battles surpassed that of the enemy, amounting to eight officers and one hundred and fifteen men.

Having been for some time detained by the necessity of making litters for the wounded, and destroying the stores which the flight of most of the horses made it impossible to transport, the army moved on, in the afternoon, to Bushy run. Here they had scarcely formed their camp, when they were again fired upon by a body of Indians, who, however, were soon repulsed. On the next day they resumed their progress towards Fort Pitt, distant about twenty-five miles; and, though frequently annoyed on the march by petty attacks; they reached their destination, on the tenth, without serious loss. It was a joyful moment both to the troops and to the garrison. The latter, it will be remembered, were left surrounded and hotly pressed by the Indians, who had beleaguered the place from the twenty-eighth of July to the first of August, when, hearing of Bouquet's approach, they had abandoned the siege, and marched to attack him. From this time the garrison had seen nothing of them until the morning of the tenth, when, shortly before the army appeared, they had passed the fort in a body, raising the scalp-yell, and displaying their disgusting trophies to the view of the English.

The battle of Bushy run was one of the best contested actions ever fought between white men and Indians. If there was any disparity of numbers, the advantage was on the side of the troops; and the Indians had displayed throughout a fierceness and intrepidity matched only by the steady valor with which they met. In the Province, the victory excited equal joy and admiration, especially among those who knew the incalculable difficulties of an Indian campaign. The Assembly of Pennsylvania passed a vote expressing their sense of the merits of Bouquet, and of the service he had rendered to the Province. He soon after received the additional honor of the formal thanks of the King.

In many an Indian village the women cut away their hair, gashed their limbs with knives, and uttered their dismal howlings of lamentation for the fallen. Yet, though surprised and dispirited, the rage of the Indians was too deep to be quenched, even by so signal a reverse; and their outrages upon the frontier were resumed with unabated ferocity. Fort Pitt, however, was effectually relieved; while the moral effect of the victory enabled the frontier settlers to encounter the enemy with a spirit which would have been wanting, had Bouquet sustained a defeat.

The two letters of Col. Bouquet following are his official report of the engagement, and they are justly regarded as very remarkable and lucid documents. They are to the Commander-in-Chief:

Camp at Edge Hill,

"26 Miles From Fort Pitt, 5th Aug., 1763.

"Sir: The second instant the troops and convoy arrived at Ligonier, where I could obtain no intelligence of the enemy. The expresses sent since the beginning of July, having been either killed or obliged to return, all the passes being occupied by the enemy. In this uncertainty, I determined to leave all the wagons, with the powder, and a quantity of stores and provisions, at Ligonier, and on the 4th proceeded with the troops and about 340 horses loaded with flour."I intended to have halted to-day at Bushy run, (a mile beyond this camp), and after having refreshed the men and horses, to have marched in the night over Turtle creek, a very dangerous defile of several miles, commanded by high and rugged hills; but at one o'clock this afternoon, after a march of seventeen miles, the savages suddenly attacked our advance guard, which was immediately supported by the two Light Infantry companies of the 42d regiment, who drove the enemy from their ambuscade and pursued them a good way. The savages returned to the attack, and the fire being obstinate on our front and extending along our flanks, we made a general charge, with the whole line to dislodge the savages from the heights, in which attempt we succeeded, without by it obtaining any decisive advantage, for as soon as they were driven from one post, they appeared on another, till, by continued reinforcements, they were at last able to surround us and attacked the convoy left in our rear; this obliged us to march back to protect it. The action then became general, and though we were attacked on every side, and the savages exerted themselves with uncommon resolution, they were constantly repulsed with loss, we also suffered considerably. Capt. Lieut. Graham and Lieut. James McIntosh of the 42d, are killed, and Capt. Graham wounded. Of the Royal American Regt., Lieut. Dow, who acted as A. D. Q. M. G., is shot through the body. Of the 77th, Lieut. Donald Campbell and Mr. Peebles, a volunteer, are wounded. Our loss in men, including rangers and drivers, exceeds sixty killed and wounded.

"The action has lasted from one o'clock till night, and we expect to begin at daybreak.

"Whatever our fate may be, I thought it necessary to give your Excellency this early information, that you may at all events take such measures as you think proper with the Provinces, for their own safety, and the effectual relief of Fort Pitt, as in case of another engagement, I fear insurmountable difficulties in protecting and transporting our provisions, being already so much weakened by the losses of this day in men and horses, besides the additional necessity of carrying the wounded, whose situation is truly deplorable.

"I cannot sufficiently acknowledge the assistance I have received from Major Campbell during this long action, nor express my admiration of the cool and steady behavior of the troops, who did not fire a shot without orders, and drove the enemy from their posts with fixed bayonets. The conduct of the officers is much above my praises.

"I have the honor to be, with great respect,

Sir, &c.,

HENRY BOUQUET.

"To His Excellency, Sir Jeffrey Amherst.""Camp at Bushy Run, 6th Aug., 1763.

"Sir: I had the honor to inform your Excellency in my letter of yesterday of our first engagement with the savages."We took the post last night on the hill where our convoy halted, where the front was attacked, (a commodious piece of ground and just spacious enough for our purpose). There we encircled the whole and covered our wounded with flour bags.

"In the morning the savages surrounded our camp, at the distance of 500 yards, and by shouting and yelping, quite round that extensive circumference, thought to have terrified us with their numbers. They attacked us early, and under favor of incessant fire, made several bold efforts to penetrate our camp, and though they failed in the attempt, our situation was not the less perplexing, having experienced that brisk attacks had little effect upon an enemy, who always gave way when pressed, and appeared again immediately. Our troops were, besides, extremely fatigued with the long march and as long action of the preceeding day, and distressed to the last degree, by a total want of water, much more intolerable than the enemy's fire.

"Tied to our convoy, we could not lose sight of it without exposing it and our wounded to fall a prey to the savages, who pressed upon us, on every side, and to move it was impracticable, having lost many horses, and most of the drivers, stupefied by fear, hid themselves in the bushes, or were incapable of hearing or obeying orders. The savages growling every moment more audacious, it was thought proper still to increase their confidence by that means, if possible, to entice them to come close upon us, or to stand their ground when attacked. With this view, two companies of Light Infantry were ordered within the circle, and the troops on their right and left opened their files and filled up the space, that it might seem they were intended to cover the retreat. The Third Light Infantry company and the Grenadiers of the 42d, were ordered to support the two first companies. This manoeuvre succeeded to our wish, for the few troops who took possession of the ground lately occupied by the two Light Infantry companies being brought in nearer to the centre of the circle, the barbarians mistaking these motions for a retreat, hurried headlong on, and advancing upon us, with the most daring intrepidity, galled us excessively with their heavy fire; but at the very moment that they felt certain of success, and thought themselves masters of the camp, Major Campbell, at the head of the first companies, sallied out from a part of the hill they could not observe, and fell upon their right flank. They resolutely returned the fire, but could not stand the irresistible shock of our men, who, rushing in among them, killed many of them and put the rest to flight. The orders sent to the other two companies were delivered so timely by Captain Bassett, and executed with such celerity and spirit, that the routed savages who happened that moment to run before their front, received the full fire when uncovered by the trees. The four companies did not give them time to load a second time, or even to look behind, but pursued them until they totally dispersed. The left of the savages, which had not been attacked, were kept in awe by the remains of our troops, posted on the brow of the hill for that purpose; nor durst they attempt to support or assist their right, but being witness to their defeat, followed their example and fled. Our brave men disdained so much as to touch the dead body of a vanquished enemy that scarce a scalp was taken except by the rangers and pack-horse drivers.

"The woods being now cleared and the pursuit over, the four companies took possession of a hill in our front, and as soon as litters could be made for the wounded, and the flour and everything destroyed, which, for want of horses, could not be carried, we marched without molestation to this camp. After the severe correction we had given the savages a few hours before, it was natural to suppose we should enjoy some rest, but we had hardly fixed our camp, when they fired upon us again. This was very provoking; however, the Light Infantry dispersed them before they could receive orders for that purpose. I hope we shall be no more disturbed, for, if we have another action, we shall hardly be able to carry our wounded.

"The behavior of the troops on this occasion speaks for itself so strongly, that for me to attempt their eulogium would but detract from their merit."

I have the honor to be, most respectfully,

Sir, &c.,

HENRY BOUQUET.

"To His Excellency, Sir Jeffrey Amherst."Return of Killed and Wounded in the Two Actions.

Forty-second, or Royal Highlanders–One captain, one lieutenant, one sergeant, one corporal, twenty-five privates killed; one captain, one lieutenant, two sergeants, three corporals, one drummer, twenty-seven privates, wounded.

Sixtieth, or Royal Americans–One corporal, six privates, killed; one lieutenant, four privates, wounded.

Seventy-seventh, or Montgomery's Highlanders–One drummer, five privates, killed; one lieutenant, one volunteer, three sergeants, seven privates, wounded.

Volunteers, rangers and pack-horse–One lieutenant, seven privates, killed; eight privates, wounded; five privates, missing.

Names of Officers.

Forty-second regiment–Captain-lieutenant John Graham, Lieutenant McIntosh, and Lieutenant Joseph Randal, of the rangers, killed.

Forty-second regiment–Captain John Graham and Lieutenant Duncan Campbell,

wounded.Sixtieth regiment–Lieutenant James Dow, wounded.

Seventy-seventh regiment—Lieutenant Donald Campbell and Volunteer Mr. Peebles, wounded.

Total–Fifty killed, sixty wounded, five missing.

Sketch of Col. Henry Bouquet.

Henry Bouquet was born at Rolle, in the Canton of Berne, Switzerland, about 1719. At the age of seventeen he was received as a cadet in the regiment of Constance, and thence passed into the service of the King of Sardinia, in whose wars he distinguished himself as a lieutenant, and afterwards as adjutant. In 1748 he entered the Swiss Guards as lieutenant-colonel. When the war broke out in 1754 between England and France he was solicited by the English to serve in America. His ability soon got him great confidence in Virginia and Pennsylvania, and he was employed in various services. He first distinguished himself under Forbes, and was one of his chief advisers. He readily fell into the provincial mode of fighting the Indians, which says more for his military genius than his former services would express. At the time of Pontiac's war, as we have seen at length, he was ordered by Gen. Amherst to relieve the western garrisons, which he did so successfully with such inefficient means. No soldier of foreign birth was so distinguished or so successful in Indian warfare as he was. The next year after this battle, that was in 1764, he was placed at the head of a force of Pennsylvania and Virginia volunteers, which he had organized at Fort Loudoun, Pa., with which he penetrated in a “line of battle” from Fort Pitt into the Indian country along the Muskingum. The savages, baffled and unsuccessful in all their attempts at surprise and ambush, sued for peace, and the "Treaty of Bouquet," made then and there, is as notorious in Ohio, as the "Battle of Bouquet" is in Pennsylvania. The Assembly of Pennsylvania and the Burgesses of Virginia adopted addresses of gratitude, tendered him their thanks, and recommended him for promotion in His Majesty's service. Immediately after the peace with the Indians was concluded, the king made him brigadier-general and commandant in the Southern colonies of British America. He lived not long to enjoy his honors, for he died at Pensacola, 1767, "lamented by his friends, and regretted universally."

______

Location of the Battle-field of Bushy Run.

Great interest, laudable in them, has always been felt and expressed by the people of Westmoreland and contiguous parts, in the personages and incidents connected with the historic battle of Bushy Run. In the May number for 1846 of the Olden Time the editor, in a note, in speaking of Bouquet's battle of Bushy Run, says: "The editor and some of his friends have frequently conversed about a visit to the battlefield, and throwing up some little work to perpetuate the memory of the precise spot. It is now, however, settled for the 5th and 6th of August next." In the August number of the same publication he says: "We have just received the 'Greensburgh Intelligencer,' containing an account of the proceedings of a preliminary meeting held at Bushy Run to make arrangements for a military encampment there on the 9th, 10th and 11th of September, in commemoration of battles fought there in August, 1763."

The battle of Bushy Run-or, as it was called by Bouquet, Edge Hill-was fought on what, afterward, was one of the manorial reservations of the Penns, called "The Manor of Denmark." The station of Manor on the Pennsylvania railroad is within its bounds. The manor contained 4,861 acres. Bushy Run is a tributary of Brush Creek, which is a branch of Turtle Creek, which flows into the Monongahela near Braddock.

The one hundred and twentieth anniversary of the battle of Bushy Run was celebrated on the grounds in a patriotic and appropriate manner, in August, 1883, on which occasion some interesting and valuable documents were first produced, and much information made popular as the result of an awakened interest in the event.

Preparatory to this anniversary commemoration the battlefield had been gone over and marked by a competent committee of gentlemen selected for that purpose. According to their report, the first day's fight, where the Forty-second Regiment, Highlanders, suffered so severely, took place on the Lewis Gongaware farm on that part of it which they designate as "The Hills." The fight around the convoy, where the savages were finally deceived into an attack and routed, took place on the Lewis Wanamaker farm, a short distance southeast of Mr. Wanamaker's present residence. The old Forbes road ran through the Wanamaker and Gongaware farms, but not on the same line as the present road, sometimes designated as the "Old Road." The engagement, speaking in general terms, took place upon the crest of a hill on a tract of land now included partly in the Wanamaker and partly in the Gongaware farm, and covers an area of perhaps one-half a mile or more in length by probably from two to three hundred yards in width. At the point where the battle culminated, the savages of course had surrounded the whites on all sides. The spring from which the water was carried in the hats of some of the more daring under cover of the night, to quench the thirst of the wounded was still pointed out. The site of the battlefield is about one and one-fourth miles east of Harrison City village, and about two miles north of Penn station, on the Pennsylvania railroad, in Penn township, Westmoreland county.

[The 160th anniversary of the battle or Bushy Run was celebrated in August. 1913, under the direction of the Westmoreland Historical Society.]