REPORT OF THE COMMISSION TO LOCATE THE SITE OF THE FRONTIER FORTS OF PENNSYLVANIA.

VOLUME TWO.

CLARENCE M. BUSCH.

STATE PRINTER OF PENNSYLVANIA.

1896.

THE FRONTIER FORTS OF WESTERN PENNSYLVANIA.

Pages 537-566.

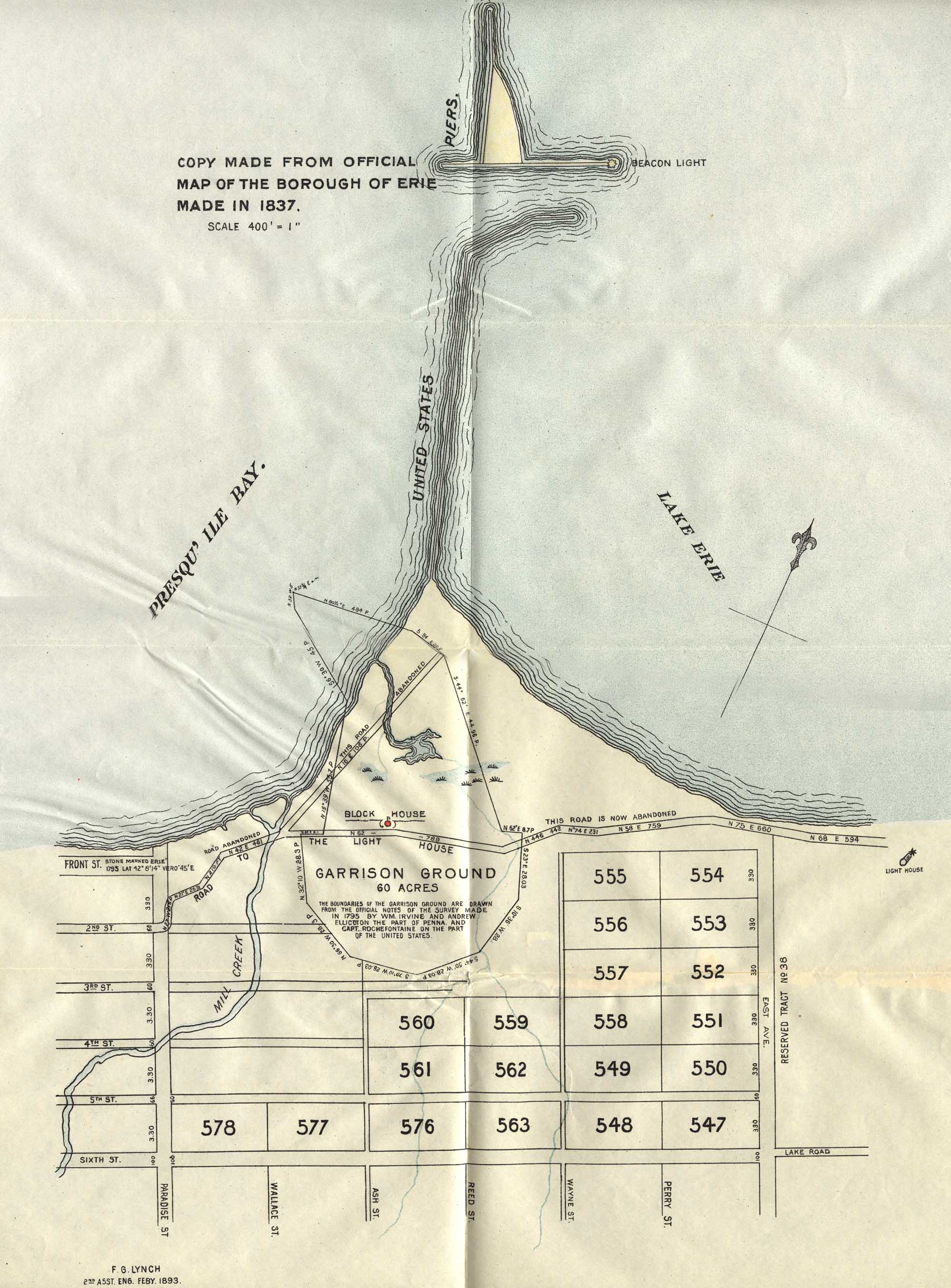

Map of the Borough of Erie, 1837.

PRESQU'ISLE.

In the preparation of that part of this report relating to Presqu'Isle and Le Boeuf, the writer had collected a large quantity of material from the sources available, and had partly arranged it, when he was offered the benefit of the History of Erie County, by Miss Laura G. Sanford. He found in the history the subject so carefully and completely treated that he gladly availed himself of the privilege of extracting from it much of the matter there collated, which he has done, following the version of the original literally wherever necessary. The excellence and historic worth of Miss Sanford's History have been much and deservedly commended. In addition to the history of these two posts, as set out in the History, the writer is indebted to Miss Sanford for additional original matter kindly furnished by her in manuscript, which has been incorporated into this report. Other authorities are referred to as they are drawn from.

In 1752 Marquis Duquesne was made Governor of Canada, and he immediately thereupon began active measures to secure possession of the territory upon which the English were encroaching. He determined to take possession of the Ohio Valley. With this design, early in 1753 a force of three hundred men, under command of Monsieur Babier, was sent out to establish military posts in this region.

It was the intention at first to build a fortification at the mouth of Chautauqua creek. Before this was done, however, Monsieur Morin arrived with a large force, and took command. That officer determined to abandon the position selected here, and, having done so, proceeded along the lake coast southwestward to the peninsula where the city of Erie, Pa., now stands. This was called by them Presqu'Isle, meaning, literally in English, "the peninsula." Here they built a fort, which was known subsequently as Fort Presqu'Isle.

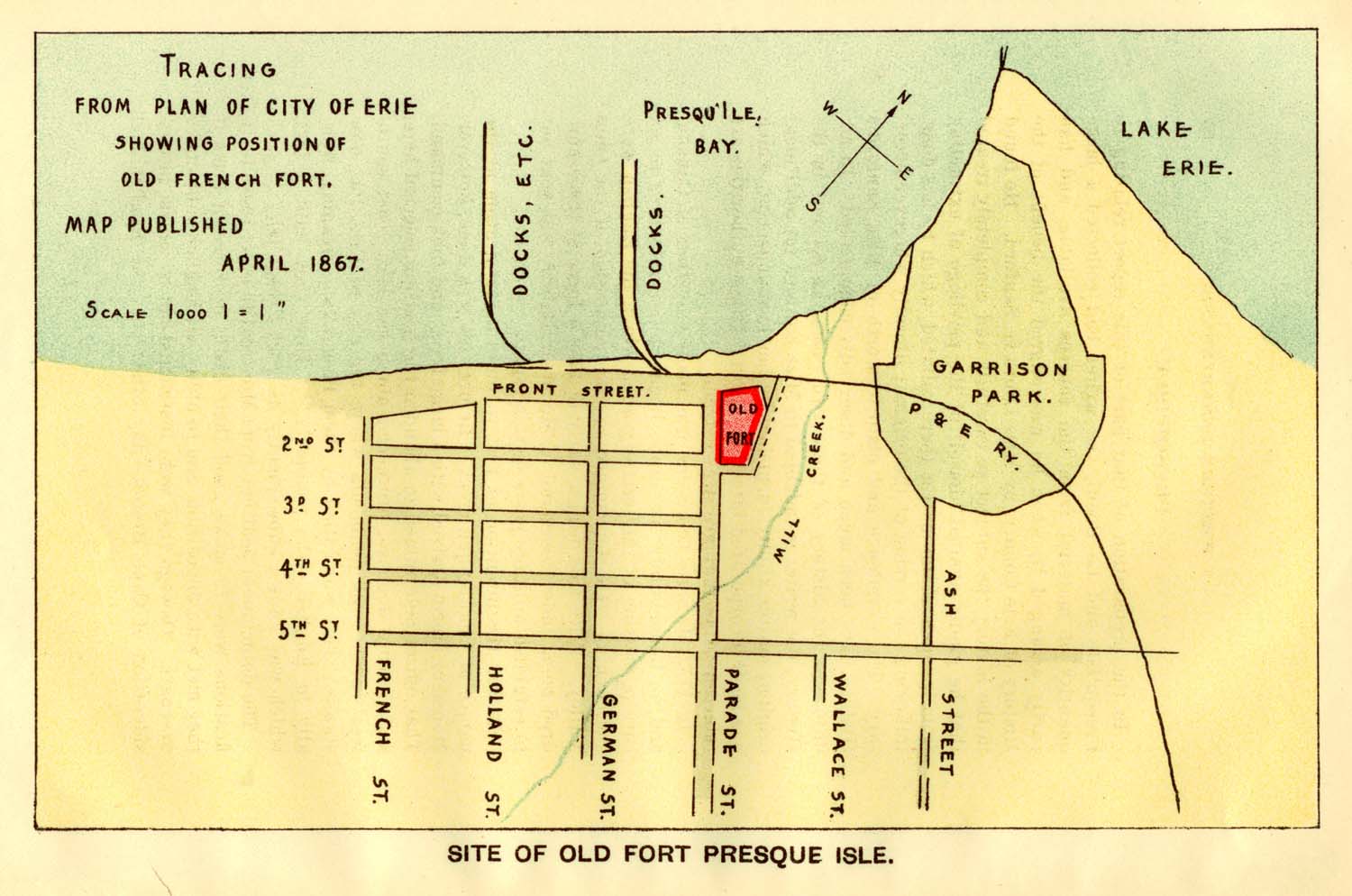

Tracing From Plan of City of Erie.

The detachment sent out from Montreal to erect these fortifications were to make good their claim by force of arms if they met with opposition, and to oblige all English subjects to evacuate. Oswego they were instructed not to molest in consideration of Cape Breton—any other post the English had settled near or claimed was to be reduced if not quitted immediately. A narrative of this expedition from Montreal, and the building of Forts Presqu'Isle and Le Boeuf, is to be found in the following deposition of Stephen Coffen, which was made to Col. Johnson, of New York, January 10th, 1754. (1.) Coffen was a New Englander who had been taken prisoner by the French and Indians of Canada, at Menis, in 1747. He had served them in different capacities until 1752, when, being detected in efforts to escape to his own country, he was confined in jail in Quebec; on his release he applied to Governor Duquesne to be sent with the forces to Ohio. In his own words, "The deponent then applied to Major Ramsey for liberty to go with the army to Ohio, who told him he would ask the Lieut. de Ruoy, who agreed to it; upon which he was equipped as a soldier and sent with a detachment of three hundred men to Montreal under the command of Mons. Babeer, who set off immediately with said command by land and ice for Lake Erie. They in their way stopped to refresh themselves a couple of days at Cadaraqui Fort, also at Taranto on the north side of Lake Ontario, then at Niagara Fort fifteen days from thence.

"They set off by water, being April, and arrived at Chadakoin (Chautauqua) on Lake Erie, where they were ordered to fell timber and prepare it for building a fort there, according to the Governor's instructions; but Mr. Morang [Morin] coming up with five hundred men and twenty Indians, put a stop to the erecting a fort at that place, by reason of his not liking the situation, and the River Chadakoin being too shallow to carry out any craft with provisions, etc., to Belle Riviere. The deponent says there arose a warm debate between Messiers Babeer and Morang [Mann] thereon, the first insisting on building a fort there, agreeable to instructions, otherwise, on Morang giving him an instrument in writing to satisfy the Governor on that point, which Morang did, and then ordered Mons. Mercie, who was both commissary and engineer, to go along said lake and look for a situation, which he found, and returned in three days, it being fifteen leagues southwest of Chadokoin. They were then ordered to repair thither; when they arrived, there were about twenty Indians fishing in the lake, who immediately quit on seeing the French. They fell to work and built a square fort of chestnut logs, squared and lapped over each other to the height of fifteen feet. It is about one hundred and twenty feet square, a log house in each square, a gate to the southward, another to the northward, not one port-hole cut in any part of it. When finished, they called it Fort Presqu'Isle. (2.) The Indians who came back from Canada with them returned very much out of temper, owing, it was said among the army, to Morang's dogged behavior and ill usage of them; but they (the Indians) said at Oswego it was owing to the French misleading them, by telling them falsehoods, which they said they now found out, and left them. As soon as the fort was finished, they marched southward, cutting a wagon road through a fine, level country twenty-one miles to the river (leaving Captain Derpontency with one hundred men to garrison the Fort Presqu'Isle). They fell to work cutting timber, boards, etc., for another fort, while Mr. Morang ordered Mons. Bite with fifty men to a place called by the Indians Ganagarahare, on the banks of Belle Riviere, where the River Aux Boeufs [French creek] empties into it. In the meantime, Morang had ninety large boats made to carry down the baggage, provisions, etc., to said place. Mons. Bite, on coming to said Indian place, was asked what he wanted or intended. He, upon answering, said ‘it was their father, the Governor of Canada's intention to build a trading house for them and all their brethren's convenience; he was told by the Indians that the lands were theirs, and that they would not have them build upon it. They said Bite reported to Morang the situation was good, but the water in the River Aux Boeufs too low at that time to carry any craft with provisions, etc.

"A few days after, the deponent says, that about one hundred Indians, called by the French the Loos, came to the Fort La Riviere Aux Boeufs to see what the French were doing; that Morang treated them very kindly, and then asked them to carry down some stone, etc., to the Belle Riviere, on horse-back, for payment, which he immediately advanced them on their undertaking to do it. They set off with full loads, but never delivered them to the French, which incensed them very much, being not only a loss, but a great disappointment. Morang, a man of very peevish, choleric disposition, meeting with those and other crosses, and finding the season of the year too far advanced to build the third fort, called all his officers together, and told them that, as he had engaged and firmly promised the Governor to finish these forts that season, and not being able to fulfill the same, he was both afraid and ashamed to return to Canada, being sensible he had now forfeited the Governor's favor forever. Wherefore, rather than live in disgrace, he begged they would take him (as he then sat in a carriage made for him, being very sick sometimes) and seat him in the middle of the fort, and then set fire to it and let him perish in the flames, which was rejected by the officers, who had not the least regard for him, as he had behaved very ill to them all in general. The deponent further saith, that about eight days before he left the Fort Presqu'Isle Chevalier Le Crake arrived express from Canada in a birch canoe worked by ten men, with orders (as the deponent afterward heard) from the Governor Le Cain (Duquesne) to Morang to make all the preparation possible against the spring of the year to build them two forts at Chadakoin, one of them by Lake Erie, the other at the end of the carrying place at Lake Chadakoin, which carrying place is fifteen miles from one place to the other. The said Chevalier brought for M. Morang a cross of St. Louis, which the rest of the officers would not allow him to take until the Governor was acquainted with his conduct and behavior. The Chevalier returned immediately to Canada.

"After which, the deponent saith, when the Fort La Riviere Aux Boeufs was finished (which is built of wood stockaded triangularwise, and has two log-houses on the inside), M. Morang ordered all the party to return to Canada in the winter season, except three hundred men, which he kept to garrison both forts and prepare materials against the spring for the building of other forts. He also sent Jean Coeur, an officer and interpreter, to stay the winter among the Indians on the Ohio, in order to prevail with them not only to allow the building of forts over there, but also to persuade them, if possible, to join the French interests against the English. The deponent further says that on the 28th of October last, he set off for Canada under the command of Capt. Deman, who had the command of twenty-two batteaux with twenty men in each batteau, the remainder being seven hundred; and sixty men followed in a few days. The thirtieth arrived at Chadakoin, where they stayed four days, during which time M. Peon, with two hundred men, cut a wagon road (portage) over the carrying place from Lake Erie to Lake Chadakoin, being fifteen miles, viewed the situation, which proved to their liking, and so set off November the third for Niagara, where we arrived the sixth. Is is a very poor, rotten, old wooden fort with twenty-five men in it. They talk of rebuilding it next summer. We left fifty men there to build batteaux against the spring, also a store-house for provisions, stores, etc. Stayed here two days, then set off for Canada. All hands, being fatigued with rowing all night, ordered to put ashore to breakfast within a mile of Oswego garrison; at which the deponent saith that he, with a Frenchman, slipped off and got to the fort, where they were concealed until the enemy passed. From thence he came here. The deponent further saith, that beside the three hundred men with which he went up first under the command of M. Babeer, and the five hundred Morang brought up afterward, there came at different times, with stores, etc., one hundred men, which made in all fifteen hundred men, three hundred of which remained to garrison the two forts, fifty at Niagara; the rest all returned to Canada, and talked of going up again this winter, so as to be there the beginning of April. They had two six-pounders, which they intended to have planted in the fort at Ganagarahare (Franklin), which was to have been called the Governor's Fort; but as that was not built, they left the guns in the fort La Riviere Aux Boeufs, where Morang commands. Further the deponent saith not." (3.)

Duquesne reporting to M. De Rauille, August 20, 1753. says, "Sieur Marin writes me on the third instant (August) that the fort at Presqu'Isle is entirely finished, that the portage road, which is six leagues in length, is also ready for carriages; that the store which was necessary to be built half way across the portage is in condition to receive the supplies, and that the second fort, which is located at the mouth of the River au Boeuf, will be soon completed."

Among the dispatches to the Marquis de Vaudreuil about this time are the following: "Presqu'Isle is on Lake Erie and serves as a depot for all the others on the Ohio; the effects are next rode to the fort on the River au Boeuf, where they are put on board pirogues to run down. * * * The Marquis de Vaudreuil must be informed that during the first campaigns on the Ohio, a horrible waste and disorder prevailed at the Presqu'Isle and Niagara carrying places, which cost the King immense sums. We have remedied all the abuses that have come to our knowledge by submitting those portages to competition. The first is at forty sous the piece, and the other, which is six leagues in extent, at fifty. * * * Hay is very abundant and good at Presqu'Isle. * * * ‘Tis to be observed that the quantity of pirogues constructed at the River au Boeuf has exhausted all the large trees in the neighborhood of that post; it is very important to send carpenters there soon to build some plank batteaux like those of the English."

From a journal kept by Thomas Forbes, a private, soldier "lately in the King of France's service," we have a description of this fort made in 1754. The journal is printed in "Christopher Gist's Journals," page 148, as edited by the late William M. Darlington, Esq., from manuscript. (4.)

"This Fort is situated on a little rising Ground at a very small Distance from the water of Lake Erie, it is rather larger than that at Niagara but has likewise no Bastions or Out Works of any sort. It is a square Area inclosed with Logs about twelve feet high, the Logs being square and laid on each other and not more than sixteen or eighteen inches thick. Captain Darpontine Commandant in this Fort and his Garrison was thirty private Men. We were eight days employed in unloading our Canoes here, and carrying the Provisions to Fort Boeuff which is built about six Leagues from Fort Presqu'Isle at the head of Buffaloe River. This Fort was composed of four Houses built by way of Bastions and the intermediate Space stockaded. Lieut. St. Blein was posted, here with twenty Men. Here we found three large Batteaus and between two or three hundred Canoes which we freighted with Provisions and proceeded down the Buffaloe River which flows into the Ohio at about twenty Leagues (as I conceived) distance from Fort au Boeuff, this river was small and at some places very shallow so that we towed the Canoes wading and sometimes taking ropes to the sore a great part of the way. When we came into the Ohio we had a fine deep water and a stream in our favor so that we rowed down that river from the mouth of the Buffaloe to Du Quesne Fort on Monongahela which I take to be seventy Leagues distant in four days and a half."

M. Pouchot, Chief Engineer of the French army in America, in his celebrated work, "Memoires sur la derniere guerre L'Amerique Septentrionale," published in 1763, makes mention of Presqu'Isle as follows, the description answering to the period of its early occupancy: "The entrance of the Lake, as far as Buffalo River (which now forms Buffalo Harbor) forms a great bay, lined with flat rocks, where no anchorage can be found. If they could keep open the mouth of the river, they would find anchorage for vessels. The coast from thence to Presqu'Isle has no shelter that is known. At Presqu'Isle there is a good bay but only seven or eight feet of water. This fort is sufficiently large; it is built piece upon piece with three outbuildings for the storage of goods in transitu. It is one hundred and twenty feet square and fifteen feet high and built on Vauban's principle, with two doors, one to the north and on the south. It is situated upon a plateau that forms a peninsula which has given its name. The country around is good and pleasant. They keep wagons for portage to Fort Le Boeuf which is six leagues. Although it is in a level country the road is not very good. The fort at Riviere au Boeuf is square, smaller than the one at Presqu'Isle, but built piece upon piece."

"In 1755 it is said three hundred and fifty-six families resided near the fort, and in 1757 there were four hundred and eighty. There were soldiers, carriers, traders, missionaries, mechanics, Indians, &c.

"Being a central point, and Fort Duquesne, Fort Niagara and Detroit on the borders, it was at times filled with stores, and one thousand men (are said) have been at one time between Presqu'Isle and Le Boeuf."

On the information of William Johnston, who had been a prisoner among the Indians for some time and who having made his escape in 1756, it is reported:

"Presqu'Isle Fort, situated on Lake Erie, about thirty miles above Buffalo Fort, is built of squared logs filled in with earth. The barracks within the fort and garrisoned with about one hundred and fifty men, supported chiefly from a French settlement begun near to it. The settlement consists, as the prisoner was informed, of about a hundred and fifty families. The Indian families about the settlement are pretty numerous; they have a priest and a schoolmaster. They have some grist mills and stills in this settlement."

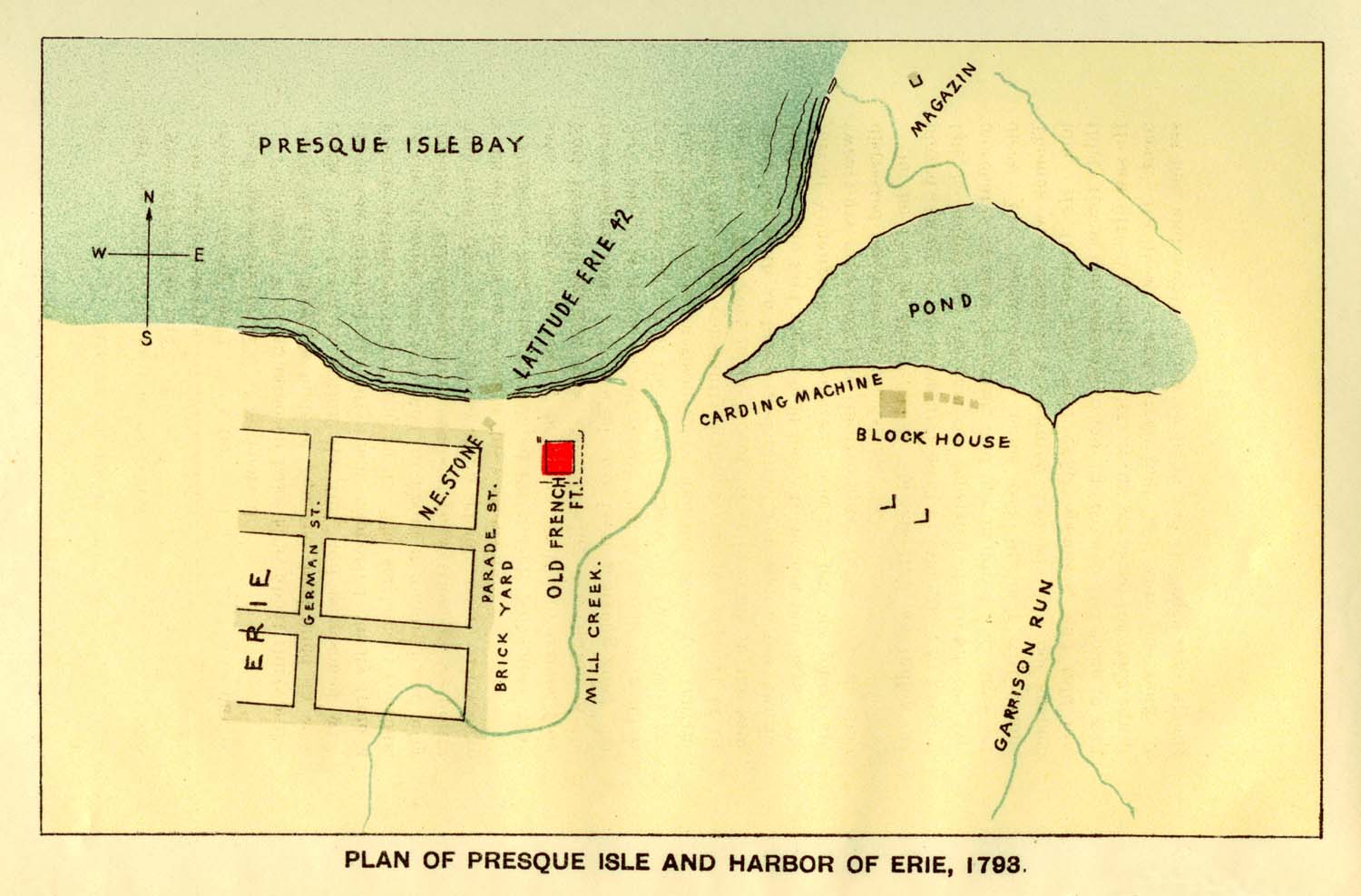

Plan of Presque Isle and Harlor of Erie, 1793.

Frederick Post's journal, dated Pittsburgh, November, 1758, says: "Just as the council broke up, an Indian arrived from Fort Presqu'Isle, and gave the following description of the three upper forts. Presqu'Isle has been a strong stockaded fort, but it is much out of repair that a strong man might pull up any log out of the earth. There are two officers and thirty-five men in garrison there, and not above ten Indians, which they keep constantly hunting, for the support of the garrison. The Fort in Le Boeuf River is much in the same condition, with an officer and thirty men, and a few hunting Indians, who said they would leave them in a few days. The fort at Venango is the smallest, and has but one officer and twenty-five men, and, like the two upper forts, they are much distressed for want of provisions." (5.)

On the 17th of March, 1750, Thomas Bull, an Indian employed as a spy at the lakes, arrived at Pittsburgh. At Presqu'Isle, he stated that the garrison consisted of two officers, two merchants, a clerk, a priest, and one hundred and three soldiers. The commandant's name was Burinol, with whom Thomas was formerly acquainted, and who did not suspect him. He treated him with great openness, and told him thirty towns had engaged to join the French and come to war. He saw fifteen hundred billets ready prepared for their equipment. He likewise understood that they were just ready to set out, and were stopped by belts and speeches sent among them by the English, but would decide when a body of over-lake Indians would arrive at Kaskaskie. Burinol described a conversation he had had with the Mingoes; that he had told them he was sorry one-half of them had broken away to the English. They replied that they had buried the tomahawk with the French; that they would do the same with the English; and wished that both would fight as they had done over the great waters, without disturbing their country; that they wished to live in peace with both, and that the English would return home. Burinol replied, that he would go home as soon as the English would move off. Thomas Bull described Fort Presqu'Isle "as square, with four bastions. They have no platforms raised yet; so they are useless, excepting in each bastion there is a place for a sentinel. There are no guns upon the walks, but four four-pounders in one of the bastions, not mounted on carriages. The wall is only of single logs, with no bank within, a ditch without. There are two gates, of equal size, being about ten feet wide; one fronts the lake, about three hundred yards distant, the other the road to Le Boeuf. The magazine is a stone house covered with shingles, and not sunk in the ground, standing in the right bastion, next the lake, going from Presqu'Isle to Le Boeuf. The other houses are of square logs. They have in store a considerable quantity of Indian goods, and but little flour. Twelve batteaux they were daily expecting from Niagara with provisions. No French were expected from Niagara, but about five hundred from a fort on the north side of the lake, in the Waweailunes country, which is built of cedar stockades. The French were to come with the Indians before mentioned. There were four batteaux at Presqu'Isle, and no works carrying on, but one small house in the fort. Some of the works are on the decay, but some appear to have been lately built. The officers made Thomas a present of a pair of stockings, and he went on to Le Boeuf, telling them that he was going to Wyoming to see his father."

"A few months after this time (March, 1759), twelve hundred regular troops were collected from Presqu'Isle, Detroit and Venango, for the defense of Fort Niagara, which had been besieged by the English under Gen. Prideaux. Four days before the conquest, the General was killed by the bursting of a cannon, and the command devolved on Sir William Johnson,. who carried out the plan with judgment and vigor, and the enemy were completely routed. The utmost confusion prevailed at Forts Venango, Presqu'Isle, and Le Boeuf after the victory, particularly as Sir William sent letters by some of the Indians to the commander at Presqu'Isle, notifying him that the other posts must be given up in a few days.

"August 13 (1759), we find that the French at Presqu'Isle had sent away all their stores, and were waiting for the French at Venango and Le Boeuf to join them, when they all would set out in batteaux for Detroit; that in an Indian path leading to Presqu'Isle from a Delaware town, a Frenchman and some Indians had been met, with the word that the French had left Venango six days before.

"About the same time, three Indians arrived at Fort du Quesne from Venango, who reported that the Indians over the lake were much displeased with the Six Nations, as they had been the means of a number of their people being killed at Niagara; that the French had burned their forts at Venango, Le Boeuf, and Presqu'Isle, and gone over the lakes. At Venango, before leaving, they had made large presents to the Indians of laced coats, hats, etc., and had told them, with true French bravado, that they were obliged to run away at this time, but would certainly be in possession of the river before the next spring. They were obliged to burn everything and destroy their batteaux, as the water was so low they could not get up the creek with them. The report was probably unfounded, of the burning of the forts, unless they were very soon rebuilt, of which we have no account." (6.)

A tradition has prevailed in Erie, that at this time treasures were buried, either in the site of the fort or on the line of the old French road. From the foregoing account, we learn that their hasty departure was made by water, and the probability is that the company returned before winter. Spanish silver coins were found twenty years ago, to the value of sixty dollars, while plowing the old site for the purpose of making brick; but, from appearances, they had been secreted there within the present century. The wells have been re-excavated time and again, but with no extraordinary results. Pottery of a singular kind has been found, and knives, bullets and human bones confirm the statements of history.

In 1760, Major Rogers was sent out by government to take formal possession for the English of the forts upon the lake, though it was not until 1763 that a definite treaty of peace was signed and ratified at Paris."

When Pontiac rose against the English, the post at Presqu'Isle was in command of Ensign Christie. The terrible ordeal which the garrison went through in that time is a marked episode of that great conspiracy, inseparably connected with its history. The account given by Mr. Parkman in his history of the conspiracy is so correct in its historical verities that it may be quoted from here, and referred to for details. (7.) The garrison, it will be remembered, was of the Royal American Regiment.

Fort Presqu'Isle stood on the southern shore of Lake Erie, at the site of the present town of Erie. It was an important post to be commanded by an Ensign, for it controlled the communication between the lake and Fort Pitt; but the blockhouse to which Christie alludes, was supposed to make it impregnable against the Indians. This blockhouse, a very large and strong one, stood at an angle of the fort, and was built of massive logs, with the projecting upper story usual in such structures, by means of which a vertical fire could be had upon the heads of assailants, through openings in the projecting part of the floor, like the machicoulis of a mediaeval castle. It had also a kind of bastion, from which one or more of its walls could be covered by a flank fire. The roof was of shingles, and might easily be set on fire; but at the top was a sentry-box or look-out, from which water could be thrown. On one side was the lake, and on the other a small stream which entered it. Unfortunately, the bank of this stream rose in a high steep ridge within forty yards of the blockhouse, thus affording a cover to assailants, while the bank of the lake offered them similar advantages on another side.

"After his visit from Cuyler, Christie, whose garrison now consisted of twenty-seven men, prepared for a stubborn defense. The doors of the blockhouse, and the sentry-box at the top, were lined to make them bullet-proof; the angles of the roof were covered with green turf as a protection against fire-arrows, and gutters of bark were laid in such a manner that streams of water could be sent to every part. His expectation of a visit from the hell-hounds proved to be perfectly well-founded. About two hundred of them had left Detroit expressly for this object. At early dawn on the fifteenth of June, they were first discovered stealthily crossing the mouth of the little stream, where the batteaux were drawn up, and crawling under cover of the banks of the lake and of the adjacent sawpits. When the sun rose, they showed themselves, and began their customary yelling. Christie, with a very unnecessary reluctance to begin the fray, ordered his men not to fire till the Indians had set the example. The consequence was, that they were close to the blockhouse before they received the fire of the garrison; and many of them sprang into the ditch, whence, being well sheltered, they fired at the loop-holes, and amused themselves by throwing stones and handfuls of gravel, or, what was more to the purpose, fire-balls of pitch. Some got into the fort, and sheltered themselves behind the bakery and other buildings, whence they kept up a brisk fire; while others pulled down a small out-house of plank, of which they made a movable breastwork, and approached under cover of it by pushing it before them. At the same time, great numbers of them lay close behind the ridges by the stream, keeping up a rattling fire into every loop-hole, and shooting burning arrows against the roof and sides of the blockhouse. Some were extinguished with water, while many dropped out harmless after burning a small hole. The Indians now rolled logs to the top of the ridges, where they made three strong breast-works, from behind which they could discharge their shot and throw their fire works with greater effect. Sometimes they would try to dart across the intervening space and shelter themselves with the companions in the ditch, but all who attempted it were killed or wounded. And now the hard-beset little garrison could see them throwing up earth and stones behind the nearest breastwork. Their implacable foes were undermining the block-house. There was little time to reflect on this new danger; for another, more imminent, soon threatened them. The barrels of water, always kept in the building, were nearly emptied in extinguishing the frequent fires; and though there was a well close at hand, in the parade ground, it was death to approach it. The only resource was to dig a subterranean passage to it. The floor was torn up; and while some of the men fired their heated muskets from the loopholes, the rest labored stoutly at this cheerless task. Before it was half finished, the roof was on fire again, and all the water that remained was poured down to extinguish it. In a few moments, the cry of fire was again raised, when a soldier, at imminent risk of his life, tore off the burning shingles and averted the danger.

"By this time it was evening. The garrison had had not a moment's rest since the sun rose. Darkness brought little relief, for guns flashed all night from the Indian intrenchments. In the morning, however, there was a respite. The Indians were ominously quiet, being employed, it seems, in pushing their subterranean approaches, and preparing fresh means for firing the blockhouse. In the afternoon the attack began again. They set fire to the house of the commanding officer, which stood close at hand, and which they had reached by means of their trenches. The pine logs blazed fiercely, and the wind blew the flame against the bastion of the blockhouse, which scorched, blackened, and at last took fire; but the garrison had by this time dug a passage to the well, and, half stifled as they were, they plied their water-buckets with such good will that the fire was subdued, while the blazing house soon sank to a glowing pile of embers. The men, who had behaved throughout with great spirit, were now, in the words of their officer, "exhausted to the greatest extremity;" yet they still kept up their forlorn defense, toiling and fighting without pause within the wooden walls of their dim prison, where the close and heated air was thick with the smoke of gunpowder. The firing on both sides lasted through the rest of the day, and did not cease till midnight, at which hour a voice was heard to call out, in French, from the enemy's intrenchments, warning the garrison that farther resistance would be useless, since preparations were made for setting the blockhouse on fire, above and below at once. Christie demanded if there were any among them who spoke English; upon which, a man in the Indian dress came out from behind the breastwork. He was a soldier, who, having been made prisoner early in the French war, had since lived among the savages, and now espoused their cause, fighting with them against his own countrymen. He said that if they yielded, their lives should be spared; but if they fought longer, they must all be burned alive. Christie told them to wait till morning for his answer. They assented, and suspended their fire. Christie now asked his men, if we may believe the testimony of two of them, ‘whether they chose to give up the blockhouse, or remain in it and be burnt alive?' They replied that they would stay as long as they could bear the heat, and then fight their way through. A third witness, Edward Smyth, apparently a corporal, testifies that all but two of them were for holding out. He says that when his opinion was asked, he replied that, having but one life to lose, he would be governed by the rest; but at the same time he reminded them of the treachery at Detroit, and of the butchery at Fort William Henry, adding that, in his belief, they themselves could expect no better usage.

When morning came, Christie sent out two soldiers as if to treat with the enemy, but, in reality, as he says, to learn the truth of what they had told him respecting their preparations to burn the blockhouse. On reaching the breastwork, the soldiers made a signal, by which their officer saw that his worst fears were well founded. In pursuance of their orders, they then demanded that two of the principal chiefs should meet with Christie midway between the breastwork and the blockhouse. The chiefs appeared accordingly; and Christie, going out, yielded up the blockhouse; having first stipulated that the lives of all the garrison should be spared, and that they might retire unmolested to the nearest post. The soldiers, pale and haggard, like men who had passed through a fiery ordeal, now issued from their scorched and bullet-pierced stronghold. A scene of plunder instantly began. Benjamin Gray, a Scotch soldier, who had just been employed, on Christie's order, in carrying presents to the Indians, seeing the confusion, and hearing a scream from a sergeant's wife, the only woman in the garrison, sprang off into the woods and succeeded in making his way to Fort Pitt with news of the disaster. It is needless to say that no faith was kept with the rest, and they had good cause to be thankful that they were not butchered on the spot. After being detained for some time in the neighborhood, they were carried prisoners to Detroit, where Christie soon after made his escape, and gained the fort in safety.

"After Presqu'Isle was taken, the neighboring posts of Le Boeuf and Venango, shared its fate; while farther southward, at the forks of the Ohio, a host of Delaware and Shawanoe warriors were gathering around Fort Pitt, and blood and havoc reigned along the whole frontier."

On the 12th of August, 1764, Col. Bradstreet and his army landed at Presqu'Isle, and there met a band of Shawanese and Delawares, who feigned to have come to treat for peace. Col. Bradstreet was deceived by them (although his officers were not), and marched to Detroit to relieve that garrison. He found Pontiac gone, but made peace with the Northwestern Indians, in which they pledged themselves to give up their prisoners; to relinquish their title to the English posts and the territory around for the distance of a cannon shot; to give up all the murderers of white men, to be tried by English law; and to acknowledge the sovereignty of the British government. Soon he discovered, as the war still raged, that he had been duped. He received orders to attack their towns; but, mortified and exasperated, his troops destitute of provisions and every way dissatisfied, he broke up his camp and returned to Niagara. Col. Bouquet afterward met the same deceptive Shawnese, Delawares, and Senecas, and succeeded in bringing them to terms; so that in twelve days they brought in two hundred and six prisoners, and promised all that could be found—leaving six hostages as security. The next year one hundred more prisoners were brought in, between whom and the Indians, in many cases, a strong attachment had sprung up, they accompanying the captives, with presents, even to the villages.

The region west of the Ohio and Allegheny rivers, prior to the year 1795, was only known as the Indian country. On the Canada side of Lake Erie there were a few white settlements. On the American side Cherry Valley, New York, was the most western settlement, and Pittsburgh the nearest settlement on the south.In the year 1782, a detachment, consisting of three hundred British soldiers and five hundred Indians, was sent from Canada to Fort Pitt. They had embarked in canoes at Chautauqua Lake, when information, through their spies, caused their project to be abandoned. Parties of Indians harrassed the settlements on the borders, and under Guyasutha, a Seneca chief, attacked and burned the seat of justice for Westmoreland county, Hannastown, and murdered several of the inhabitants.

In 1785, Mr. Adams, Minister at London, writes to Lord Carmarthan, English Secretary of State: "Although a period of three years had elapsed since the signature of the preliminary treaty, and more than two years since the definitive treaty, the posts of Oswegatchy, Oswego, Niagara, Presqu'Isle, Sandusky, Detroit, Mackinaw, with others not necessary particularly to enumerate, and a considerable territory around each of them, all within the incontestable limits of the United States, are still held by British garrisons to the loss and injury of the United States," etc. As we do not hear from any other source of the rebuilding of the fort at Presqu'Isle or of a garrison there, the probability is that Mr. Adams only had reference to Presqu'Isle as an important strategic point. (8.)

The Indians being recognized as owners of the soil, the whole was purchased from them by different treaties; one at Fort Stanwix, now Rome, extinguished their title to the lands of Western Pennsylvania and New York, excepting the Triangle or Presqu'Isle lands, which were accidentally left out of Pennsylvania, New York, Massachusetts, Connecticut, and Virginia, and were supposed at different times to belong to each. Gen. Irvine discovered, while surveying the donation lands, that Pennsylvania had but a few miles of lake coast, and not any harbor, and in consequence of his representations, the State of Pennsylvania made propositions for its purchase to the United States government, which sent out Surveyor-General Andrew Ellicott, for the purpose of running and establishing lines.

As the line was to commence at the west end of Lake Ontario, there was some hesitation whether the western extremity of Burlington Bay or the peninsula separating the bay from the lake was intended. It was finally fixed at the peninsula, and by first running south, and then offsetting around the east end of Lake Erie, the line was found to pass twenty miles east of Presqu'Isle. This line, as it was found to comply with the New York charter, being twenty miles west of the most westerly bend of the Niagara river, became the western boundary of the State of New York between Lake Erie and the old north line of Pennsylvania, and the east line of the tract known as the Presqu'Isle Triangle, which was afterward purchased by Pennsylvania of The United States. Massachusetts charter, in 1785, comprehended the same release that New York had given, and that of Connecticut which retained a reservation of one hundred and twenty miles lying west of Pennsylvania's western boundary. On the 6th of June, 1788, the board of treasury was induced to make a contract for the sale of this tract described as bounded on the east by New York, on the south by Pennsylvania, and on the north and west by Lake Erie. On the 4th of September, it was resolved by Congress that The United States do relinquish and transfer to Pennsylvania all their right, title and claim to the government and jurisdiction of said land forever, and it is declared and made known that the laws and public acts of Pennsylvania shall extend over every part of said tract, as if the said tract had originally been within the charter bounds of said State. By an act of the 2d of October, 1788, the sum of twelve hundred pounds was appropriated to purchase the Indian title to the tract, in fulfillment of the contract to sell it to Pennsylvania. At the treaty of Fort Harmar, on the 9th of January, 1789, Cornplanter and other chiefs of the Six Nations signed a deed, in consideration of the sum of twelve hundred pounds, ceding the Presqu'Isle lands of the United States to be vested in the State of Pennsylvania, and on the 13th of April, 1791, the Governor was authorized to complete the purchase from the United States, which, according to a communication from him to the Legislature, was accomplished in March, 1792; and the consideration—amounting to $151,640.25—paid in continental certificates of various descriptions. A draft annexed to the deed of the Triangle shows it to contain two hundred and two thousand one hundred and eighty-seven acres.

An amusing anecdote, relating to the period of these surveys, is mentioned in Pennsylvania Historical Collections: "When Mr. William Miles set off with a corps of surveyors for laying out the donation lands, the baggage, instruments, etc., were placed in two canoes. Fifteen miles above Pittsburgh, at the last white man's cabin on the river, the party stopped to refresh themselves, leaving the canoes in the care of the Indians. On returning to the river, all was gone—canoes and Indians had all disappeared. Mr. Miles asked if any one had a map of the river. One was fortunately found, and by it they discovered the river had a great bend just where they were. Their compass was gone, but, by means of Indian signs, mosses on trees, etc., they found their way out above the bend, secreted themselves in the bushes, and waited for the canoes to come up, which happened very soon. When the old chief found he had been detected, he cooly feigned ignorance and innocence, and, stepping out of the canoe with a smile, greeted the surveyors with ‘How do? ‘How do? "

The treaty of peace with Great Britain, in 1783, was followed by a treaty with the Six Nations, at Fort Stanwix, in October, 1784. At the latter, the Commissioners of Pennsylvania secured from the Six Nations the relinquishment of all the territory within the State northwest of the boundary of 1768. This purchase was confirmed by the Delawares and Wyandots, in January, 1785, at Fort McIntosh. The boundary between Pennsylvania and New York was run out in 1785, ‘86 and ‘87, partly by David Rittenhouse, and afterwards by Andrew Ellicott and other commissioners on the part of New York.

On the 3d of March, 1792, Pennsylvania purchased the tract from The United States, and a deed of that date confirmed it to the State. (10.)

On the 8th of March, 1793, the Pennsylvania Population Company was formed for the purpose of encouraging settlements on the lands which they had purchased, lying in this part of the State.

A month after (April, 1793) the formation of this company, an act passed the Legislature for laying out a town at Presqu'Isle, "in order to facilitate and promote the progress of settlement within the Commonwealth, and to afford additional security to the frontiers thereof."

Gov. Mifflin transmitted to the President of the United States a copy of this act, apprehending the difficulties which soon manifested themselves. Prior to this he had sent to Capt. Denny a commission, appointing him captain of the Allegheny company, and instructing him to engage four sergeants, four corporals, one drummer and fifer, two buglers, and sixty-five rank and file, or privates, and to stipulate with the men to remain longer than the appointed eight months, should the state of the war require it. Early in the month of May, Messrs. Irvine, Ellicott and Gallatin were to engage in laying out the town, with Capt. Denny's company to protect and defend them. For the same object, a post had been established at Le Boeuf, two miles below the site of the old fort, and all persons employed by government were particularly cautioned against giving offense to the English or British garrisons in that quarter. A letter from Gen. Wilkins, at Fort Franklin, to Clement Biddle, quartermaster-general of Pennsylvania, informs us of his arrival, with forty of Capt. Denny's men and thirty volunteers from the county of Allegheny, and that the news was not favorable toward an establishment at Presqu'Isle. Those most conversant with the Indians were of opinion that they were irritated by the British, and meditated an opposition to the government, and that the question of peace or war depended upon a council then convened at Buffalo creek. To this council Cornplanter and other Indians on the Allegheny river had been invited; and as the English had summoned it, the prospect was not favorable for peace.

The disturbed conditions of the country owing to the frontier war then going on, were not favorable to this project. In the meantime Presqu'Isle was put on a war footing, and a garrison stationed there. The papers relating to the Presqu'Isle establishment are found in the Sixth Volume of the Second Series of Penna. Archives.

All difficulties being removed, April 18th, 1795, an act passed the Legislature to lay out a town at Presqu'Isle, at the mouth of French creek, at the mouth of Conewango creek, and at Le Boeuf—being the towns of Erie, Franklin, Warren and Waterford.

Two commissioners were appointed by the Governor to survey at Presqu'Isle sixteen hundred acres for town lots, and thirty-four hundred adjoining for out lots (the three sections of about a mile each, only one-half of which is now occupied), to be laid out into town lots and out lots; the streets not less than sixty feet in width, nor more than one hundred; no town lots to contain more than one-third of an acre; no out lots more than five acres; and the reservation for public uses not to exceed in the whole twenty acres. After the commissioners had returned the surveys into the office of the secretary, the Governor was to offer at auction one-third of the town lots and one-third of the out lots, upon the following conditions; that within two years one house be built at least sixteen feet square, with at least one stone or brick chimney. Patents were not to be issued till the same was performed, and all payments to be forfeited to the Commonwealth in case of failure. (This condition was afterward repealed.) Exclusive of the survey of lots and out lots, sixty acres were reserved on the southern side of the harbor of Presqu'Isle for the accommodation of the United States, in the erection of necessary forts, magazines, dock-yards, etc.; thirty acres to be on the bank, and the remainder below, comprehending the point at the entrance of the harbor; and upon the peninsula thirty acres at the entrance of the harbor, and one other lot of one hundred acres. The situation and forms of these lots were to be fixed by the commissioners and an engineer employed by the United States. Andrew Ellicott had previously surveyed and laid out Waterford, and an act was now passed to survey these five hundred acres, and to give actual settlers the right of pre-emption.

Deacon Hinds Chamberlain, of LeRoy, New York, in company with Jesse Beach and Reuben Heath, journeyed to Presqu'Isle in 1795. Deacon Chamberlain describes the tour as follows: "We saw one white man, named Poudery, at Tonawanda village. At the mouth of Buffalo creek there was but one white man named Winne, an Indian trader. His building stood just beyond as you descend from the high ground (near where the Mansion House now stands, corner of Main and Exchange streets). He had rum, whisky, Indian knives, trinkets, etc. His house was full of Indians, and they looked at us with a good deal of curiosity. We had but a poor night's rest—the Indians were in and out all night getting liquor. The next day we went up to the beach of the lake to the mouth of Cattaraugus creek, where we encamped; a wolf came down near our camp, and deer were quite abundant. In the morning went up to the Indian village; found ‘Black Joe's house, but he was absent. He had, however, seen our tracks upon the beach of the lake, and hurried home to see what white people were traversing the wilderness. The Indians stared at us; Joe gave us a room where we should not be annoyed by Indian curiosity, and we stayed with him over night. All he had to spare us in the way of food was some dried venison; he had liquor, Indian goods, and bought furs. Joe treated us with so much civility that we remained until near noon. There were at least one hundred Indians and squaws gathered to see us. Among the rest were some sitting in Joe's house, an old squaw and a young, delicate-looking white girl dressed like a squaw. I endeavored to find out something about her history, but could not. She seemed inclined not to be noticed, and had apparently lost the use of our language. With an Indian guide provided by Joe we started upon the Indian trail for Presqu'Isle.

"Wayne was then fighting the Indians, and our guide often pointed to the West, saying, ‘bad Indians there.' Between Cattaraugus and Erie I shot a black snake, a racer, with a white ring around his neck. He was in a tree twelve feet from the ground, his body wound around it, and measured seven feet and three inches.

"At Presqu'Isle (Erie) we found neither whites nor Indians —all was solitary. There were some old French brick buildings, (why did they make bricks, surrounded as they were by stone and timber?) wells, blockhouses, etc., going to decay, and eight or ten acres of cleared land. On the peninsula there was an old brick house forty or fifty feet square. The peninsula was covered with cranberries.

"After staying there one night we went over to Le Boeuf, about sixteen miles distant, pursuing an old French road. Trees had grown up in it, but the track was distinct. Near Le Boeuf we came upon a company of men who were cutting out the road to Presqu'Isle—a part of them were soldiers and a part Pennsylvanians. At Le Boeuf there was a garrison 0f soldiers—about one hundred. There were several white families there, and a store of goods. Myself and companions were in pursuit of land. By a law of Pennsylvania, such as built a log-house and cleared a few acres acquired a presumptive right—the right to purchase at five dollars per hundred acres. We each of us made a location near Presqu'Isle. On our return to Presqu'Isle from Le Boeuf, we found there Col. Seth Reed and his family. They had just arrived. We stopped and helped him to build some huts; set up crotches, laid poles across, and covered them with the bark of the cucumber tree. At first the Col. had no floors; afterward he indulged in the luxury of floors by laying down strips of bark. James Baggs and Giles Sisson came on with Col. Reed. I remained for a considerable time in his employ. It was not long before eight or ten other families came in.

"On our return we again stayed at Buffalo over night with Winne. There was at the time a great gathering of hunting parties of Indians there. Winne took from them all their knives and tomahawks, and then selling them liquor, they had a great carousal."

Capt. Martin Strong, in a letter to William Nicholson, Esq., dated Waterford, January 8th, 1855, says: "I came to Presqu'Isle the last of July, 1795. A few days previous to this a company of United States troops had commenced felling the timber on Garrison Hill, for the purpose of erecting a stockade garrison; also a corps of engineers had arrived, headed by Gen. Ellicott, escorted by a company of Pennsylvania militia, commanded by Capt. John Grubb, to lay out the town of Erie.

"We all were in some degree under martial law, the two Rutledges having been shot a few days before (as was reported by the Indians) near the site of the present Lake Shore railroad depot. Thomas Rees, Esq., and Col. Seth Reed and family (the only family in the Triangle) were living in tents and booths of bark, with plenty of good refreshments for all itinerants that chose to call, many of whom were drawn here from motives of curiosity and speculation. Most of the land along the lake was sold this summer at one dollar per acre, subject to actual settlement. We were then in Allegheny county. * * * Le Boeuf had a small stockade garrison of forty men, located on the site of the old French fort; a few remains of the old entrenchment were then visible. In 1795 there were but four families residing in what is now Erie county. These were of the names of Reed, Talmage, Miles and Baird. The first mill built in the Triangle was at the mouth of Walnut creek; there were two others built about the same time in what is now Erie county; one by William Miles, on the north branch of French creek, now Union; the other by William Culbertson, at the inlet of Conneautee Lake, near Edinboro."

"The next year (1796) Gen. Wayne received an appointment from the Government to conclude a treaty with the Northwestern Indians, and having accomplished this arduous task, embarked at Detroit, in the sloop Detroit, for the purpose of returning to his home in Chester county. Soon after leaving port he was violently attacked by his old malady, the gout, and the usual remedy, brandy, through an oversight of the steward, not being at hand, he became very much prostrated, and in this condition was landed at Erie. As there was no resident physician of any repute, Dr. J. C. Wallace, a skillful surgeon of the army, then at Pittsburgh, was sent for with the greatest despatch, but on arriving at Franklin, met a messenger with the news of his death.

"When Gen. Wayne was brought into the garrison, he expressed a wish to be placed in the northwest blockhouse, the attics of the blockhouses being comfortably fitted up and occupied by the families connected with the garrison. Capt. Russel Bissell probably had command at the time, and it is said the illustrious sufferer met with every possible kindness.

"A fit death-bed and silent resting-place for a brave officer and patriot was the old military post of Presqu'Isle and its picturesque bay. He named the spot for his grave at the foot of the flagstaff. ‘A. W.' on a single stone was placed at the head, and a neat railing inclosed it." The remains were removed in 1809 by a son, Col. Isaac Wayne, of Chester county, and deposited in Radnor church yard (St. David's Episcopal church), which is fourteen miles west of Philadelphia. Dr. J. C. Wallace superintended the disinterment of the body, which was found in a remarkable state of preservation.

On a monument erected by the Pennsylvania Society of the Cincinnati is found the following:

"Major-General Anthony Wayne was born at Waynesboro, in Chester county, Pennsylvania, in 1745. After a life of honor and usefulness, he died in December, 1796, at Erie, Pennsylvania, then a military post on Lake Erie, Commander-in-Chief of the Army of the United States. His military-achievements are consecrated in the history of his countrymen. His remains are here deposited."

For the better defense of Erie, in the winter of 1813 and 1814, a blockhouse was built on Garrison Hill, and another on the point of the peninsula. (The one on the shore was burned in 1853, an occurrence much regretted by the inhabitants.)

See Plan of Presque Isle and Harbor of Erie, 1793.

"Fort Presqu'Isle was on the table land where now stands the city of Erie. It was at the intersection of the south shore of the harbor with the west bank of Mill creek, about fifty-five feet above the level of the lake, and commanded the mouth of Mill creek, which is supposed to have been the point of debarkation from arriving vessels. The site has been effectually scraped and carted away in the course of improvements, and could be best described as bounded north by Erie harbor, east by Mill creek, south by Second street, and west by Parade street." Thus far we have the words of Col. John H. Bliss, one of Erie's citizens, the grandson of Major Andrew Ellicott.

"It may be remarked that Mill creek at an early day was a much larger stream than at present, and in 1819, when our map was drawn, a brick yard and a carding machine were occupying much the same ground. At this time [1895] Messrs. Paradine and McCarty own and occupy the site as a brick yard, having lowered the ground about thirty feet, and their intention is to lower still further. The precise site of the fort in excavating was marked by remnants of knives, muskets, &c., much decomposed."

"The Northeast corner-stone of the city stood a little northwest of it—say, half a block distant." (11.)

"After the site was found in 1876 the State erected a blockhouse on the exact site to mark the grave of General Wayne. That blockhouse is still there, and is comprehended in the grounds of the Pennsylvania Sailors and Soldiers Home. It is a short distance north of the Soldiers Home buildings, across the tracks of the Pennsylvania and Erie railway, which are spanned by a bridge. The Soldiers Home occupies the grounds marked on the map as ‘Garrison Ground' or ‘Park. '" (12.)

Notes to Presqu'Isle.(1.) The deposition of Stephen Coffen is in the Pennsylvania Archives, Vol. vi, Second series.

(2.) From "The Examination of J. B. Pidon, a French Deserter," Arch., ii, 125, taken March 7th, 1754, it would seem that the original name of this fort was Duquesne. He states that in the spring of 1753, "They went in batteaux through the Lake Ontario and the straights of Niagara, and sailed six or seven days in Lake Erie, after which they landed and began to build a fort on an eminence, about one hundred yards from the bank of the lake, which they called Duquisne, the name of their general, the Marquis Duquisne."

(3.) These papers are collected in the Sixth volume of Penna. Archives, Second series.

(4.) Printed at Pittsburgh, 1893.(5.) These authorities are given in Third Archives, and quoted in the History of Erie County.

(6.) The forts were set on fire, and from all accounts were burnt, but it is probable that when the sites were taken by the English subsequently, they utilized some of the material, such as the stone, for instance, in the construction of their forts or blockhouses.

(7.) Conspiracy of Pontiac, Vol. i, p. 280.

Of this event a version which seems to be looked upon favorably by local historians, and which is frequently quoted, is here given. There appears to be some substantial details preserved, which might furnish a clew for further inquiries; but where the article conflicts with the version of Mr. Parkman, it must be remembered that the version of Mr. Parkman was founded upon the statements of those who participated in the affair, or from contemporaneous historical papers; among other sources, for instance, were the Report of Ensign Christie, The Testimony of Edward Smyth, MS., taken by order of Col. Bouquet, and the statements of the soldiers, Gray and Smart, who escaped.

With this explanation, the account of Mr. Harvey is here inserted. It is taken from Miss Sanford's History of Erie County:

"Mr. H. L. Harvey, formerly editor of the Erie Observer, a gentleman of research and integrity, in a lecture delivered in Erie, introduced the following account of the same event, differing, as will be seen, from the above-named accredited historian as also from Bancroft. He says: ‘The troops retired to their quarters to procure their morning repast; some had already finished, and were sauntering about the fortress or upon the shore of the lake. All were joyous in holiday attire, and dreaming of naught but the pleasure of the occasion. A knock was heard at the gate, and three Indians were announced in hunting garb, desiring an interview with the commander. Their tale was soon told. They said they belonged to a hunting party, who had started for Niagara with a lot of furs; that their canoes were bad, and they would prefer disposing of them here, if they could do so to advantage, and return, rather than go farther; that their party were encamped by a small stream west of the fort about a mile, where they had landed the previous night, and where they wished the commander to go and examine their peltries, as it was difficult to bring them, and they wished to embark where they were, if they did not trade. The commander, accompanied by a clerk, left the fort with the Indians, charging his Lieutenant that none should leave the fort, and none be admitted, until his return. Well would it probably have been had his order been obeyed. After the lapse of sufficient time for the captain to visit the encampment of the Indians and return, a party of the latter, variously estimated—probably one hundred and fifty—advanced toward the fort, bearing upon their backs what appeared to be large packs of furs, which they informed the lieutenant the captain had purchased and ordered deposited in the fort. The stratagem succeeded; when the party were all within the fort, it was the work of an instant to throw off their packs and the short cloaks which covered their weapons, the whole being fastened by one loop and button at the neck. Resistance at this time was useless, and the work of death was as rapid as savage strength and weapons could make it. The shortened rifles, which had been sawed off for the purpose of concealing them under their cloaks and in the packs of furs, were at once discharged, and the tomahawk and knife completed their work. The history of savage warfare presents not a scene of more heartless and bloodthirsty vengeance than was exhibited on this occasion. The few who were taken prisoners in the fort were doomed to the various tortures devised by savage ingenuity, and all but two who awoke to celebrate that day, had passed to the eternal world. Of these, one was a soldier who had gone into the woods near the fort, and on his return observing a party of Indians dragging away some prisoners, escaped, and immediately proceeded to Niagara; the other was a soldier's wife, who had taken shelter in a small stone house, at the mouth of the creek, used as a wash-house. Here she remained unobserved until near night of the fatal day, when she was made their prisoner, but was ultimately ransomed and restored to civilized life. She was afterward married, and settled in Canada, where she was living at the commencement of the present century. Capt. D. Dobbins, of the revenue service, has frequently talked with the woman, who was redeemed by a Mr. Douglass, living opposite Black Rock, in Canada. From what she witnessed, and heard from the Indians during her captivity, as well as from information derived from other sources, this statement is made. "

(8.) History of Erie Co., supra, p. 54.

(9.) History of Erie Co., p. 60.

(10.) Day's Historical Collections of Penna., p. 315.

The extracts cited here following are from the History of Erie Co., supra.

(11.) Miss Laura G. Sanford, MS.

(12.) George Platt, Esq., City Engineer, Erie, MS.

To Mr. Platt we are indebted for the map above referred to. For the official reports and papers relating to the establishment of Presqu'Isle, see the Sixth volume of Penna. Archives, sec. ser.

"East of this early settlement in New France, excavations show that brick made there was of French measure. The old inhabitants of this region speak of a ‘French stone chimney,' as it was called, opposite Big Bend on the Peninsula— that it was made of brick and used as a watch house. Fishermen have made a thorough distribution of these bricks long ago. The ‘Sixteen Chimneys,' one of the forts was said to have, also refers to their manufacture of brick." [Miss Laura G. Sanford, MS.]

The chain of title to the site of the blockhouse property is as follows:

Chain of title to all that certain piece of land situate in the city of Erie, County of Erie, and State of Pennsylvania, bounded and described as follows, to wit: Beginning on the northeast corner of Parade street and Second street; thence northwardly along said Parade street 330 feet to Front street; thence by the south line of the said Front street produced eastwardly six hundred and thirty (630) feet to a point where the west line of Wallace street produced would intersect; thence along the channel of Mill creek south one degree and thirty minutes (1° 30'), west three hundred and eighty (380) feet to second street; thence westwardly along said Second street four hundred and fifty (450) feet to Parade street, at the place of beginning, containing about four and one-tenth (4-1/10) acres.

The records of Erie county were destroyed by fire on March 23d, 1823.

William G. Snyder to James O'Hara. Deed dated June 10th, 1803, and recorded June 10th, 1824, in deed book J B, page 85.

For a valuable consideration, assign and set over all my right, title, interest and claim in and to a tract of land adjoining the city of Erie, containing fifty acres.

Robert McKnight and Wm. M. Paxton, executors of Elizabeth F. Denny, dec'd, and heirs of decedent, to Mary O'Hara Spring. Partition deed dated December 18th, 1879, and recorded December 30th, 1879, in deed book No. 65, page 283.

* * * * To Mary O'Hara Spring is allotted the premises described in the caption hereto (with other property) acknowledged December 18th, 1879.

Mary O'Hara Spring to Thomas J. Paradine and James McCarty. Warranty deed dated May 5th, 1888, and recorded November 3d, 1888, in deed book No. 92, page 199; consideration, $5,000.

Grants bargains, sells, etc., the premises described in the caption hereto, acknowledged May 5th, 1888.

Thomas J. Paradine and Mary, his wife, to James McCarty. Warranty deed dated January 3d, 1893, and recorded November 3d, 1893, in deed book No. 109, page 364; consideration, $8,000.

Grants, bargains, sells, etc., the undivided one-half of the premises described in the caption hereto, acknowledged January 3d, 1893.

______