REPORT OF THE COMMISSION TO LOCATE THE SITE OF THE FRONTIER FORTS OF PENNSYLVANIA.

Volume Two.

Clarence M. Busch. State Printer of Pennsylvania, 1896.

FRONTIER FORTS OF WESTERN PENNSYLVANIA.

by George Dallas Albert.

Introductory and Notes.

Pages 3-23.

The contention between Great Britain and France for the possession of the territory which is now Western Pennsylvania, began about the middle of the last century. The treaty of Aix la Chapelle, signed October 1st, 1748, while it nominally closed the war between those two countries, failed to establish the boundaries between their respective colonies in America; and this failure, together with the hostile and conflicting attitude of the colonists in America, were the causes of another long and bloody war.

The Ohio Company was an association formed in Virginia about the year 1748, under a royal grant. The nominal object of the charter association was to trade with the Indians, to divert it southward along the Potomac route, and to settle the region about the Ohio with English colonists from Virginia and Maryland. That it was intended to be a great barrier against the encroachments of the French, is manifest. Its privileges and concessions were large and ample. (1.)

All the vast extent of this country from the Mississippi to the Allegheny mountains, bordered by the great lakes on the north, had been explored, and to a certain degree occupied by the French. They had their forts, trading post & and missions at various points, and they tried by every possible means to conciliate the Indians. It was apparent that they would shortly extend their occupancy to the most extreme tributaries of the Ohio, which they claimed by virtue of prior discovery. (2.) And while the English by their fur-traders and agents and now by the active cooperation of their Virginia colonists under the auspices of this company, sought to gain a permanent occupancy of the Ohio Valley, the French began actively to assert their claims to the same region. Thus the formation of the Ohio Company, the intrusion of Indian traders, and the occupancy of some colonial families at the favorite trading posts on the Ohio and its tributaries, hastened the action of the French in taking possession of this region under their persistently asserted claims.

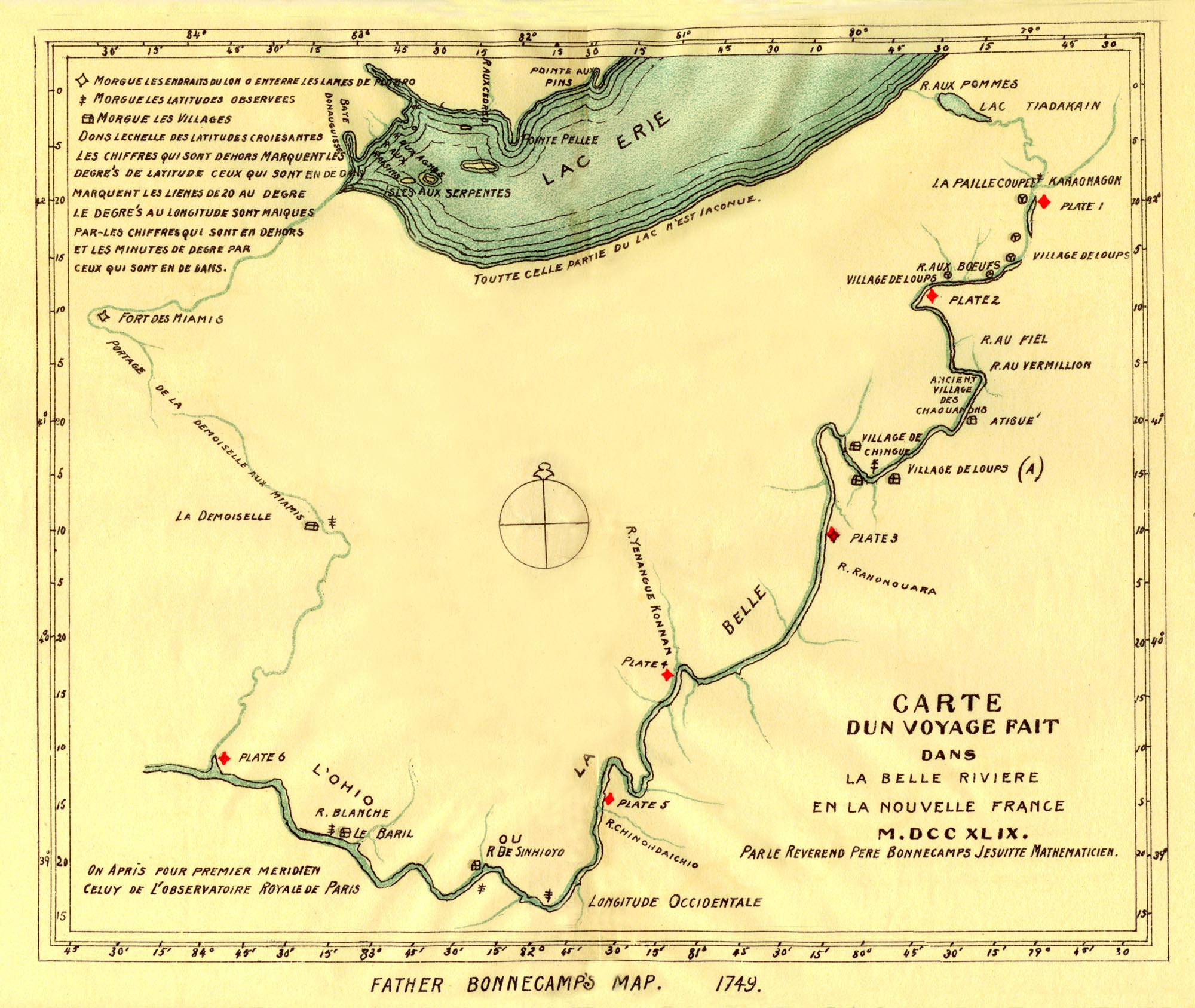

Thereupon to counteract the designs of the English, the Governor-General of Canada, the Marquis de la Galissoniere, (3) sent Celoron (4) in 1749 down the Allegheny and Ohio rivers, to take possession of the country in the name of the King of France. His command consisted of 215 French and Canadian soldiers and 55 Indians of various tribes. The principal officers under him were Contrecoeur, (5) who afterwards built Fort Duquesne, Coulon de Villiers, (6) and Joncaire-Chabert. (7.)

Provided with a number of leaden plates, they left La Chine, above Montreal, on the 15th of June, 1749, and ascending the St. Lawrence to Lake Ontario, they coasted along its shore till they reached Fort Niagara on the 6th of July. Pursuing their course they arrived at a point on the southern shore of Lake Erie, where they disembarked. (8.) By means of Chautauqua creek, a portage, Chautauqua Lake and Conewango creek, they came, on the 29th, to the Allegheny river, near the point now occupied by the town of Warren, in Warren county, Pa. The first of the leaden plates was buried at this point. (9.) By these persisting inscriptions and proclamations made with much ceremony, they asserted their nominal possession of the Ohio, regarding the Allegheny as but a continuation of that river. Notwithstanding their endeavors to strengthen the attachment of the Indians to their cause, they found that all along the Allegheny there was a strong bias in their feelings in favor of the English. Continuing their descent of the Allegheny and the Ohio, and entering some of the tributaries of the latter, they deposited at various points these plates, each differing in some minor particulars from the others. When they came to the mouth of the Miami river, they ascended that stream, and thence crossed by a portage to the head waters of the Maumee, descending which they reached Lake Erie and returned to Montreal, arriving there on the 10th of November, 1749.

The way thus opened, the French visited the Allegheny river region, but did not establish permanent posts there. They, however, made constant effort to conciliate the Indians and to arouse them in an antagonism against the English. Their affairs were committed to Joncaire-Chabert, who was vigilant in his labors with the natives. He occupied mostly the house at the mouth of French creek, or Venango, which had been built by John Frazer, a Pennsylvania trader, whom Celoron found there, and whom he drove off. (10.)

The Governor-General of Canada, (Marquis de la Jonquiere) having died in 1752, he was succeeded by the Marquis du Quesne. This energetic official was hindered by difficulties in his anxious desire to occupy this region by force, but at length the movements of the English hastened his action. Early in January, 1753, an expedition consisting of three hundred men under command of Mons. Babeer (Babier) set out from Quebec and journeying by land and ice, arrived at Fort Niagara in April. After resting there fifteen days, they continued their course by water to the southeastern shore of Lake Erie. Disembarking at Chadakoin [Chautauqua], at the mouth of Chattauqua creek, where Celoron had disembarked four years before, they prepared to build a fort. The command of the expedition was here assumed by Monsieur Morin, who about the end of May, arrived with an additional force of five hundred whites and twenty Indians. (11.) The Chautauqua creek had been adopted as the route by Celoron, but now finding it too shallow to float canoes or batteaux, he passed further to the west and came to a place which, from the peculiar formation of the lake shore, they named Presqu' Isle, or the Peninsula. This is now the site of the City of Erie. Here the first fort, which was named Fort la Presqu' Isle, was built. (12.) It was constructed of square logs, was about one hundred ana twenty feet square, and fifteen feet high, but had no port-holes, and was probably finished in June, 1753.

When the fort was finished it was garrisoned by about one hundred men, under command of Captain Depontency. The remainder of the forces commenced cutting a road southward to the headquarters of Le Boeuf river, or French creek. This was a distance of about fifteen miles, and is the site of the present village of Waterford, Erie county, Pa. Here they built a second fort, similar to the first, but smaller. (13.)

The season was too late to build the third fort, which they had been ordered to do; and thereupon, after leaving a large force of their men to garrison these two forts, the rest returned for the winter to Canada. (14.)

The tidings of these things startled the middle colonies, and especially alarmed the Governor of Virginia, who late in the year 1753, despatched a messenger to demand of the French an explanation of their designs. George Washington, then a youth who had but shortly attained his majority, was the person selected for the mission by Governor Dinwiddie. He performed his duty with the greatest tact and to the satisfaction of his government. With seven of a party besides himself, among whom was Christopher Gist (15) a person admirably adapted for such a service, he started out on the 15th of November from Wills creek - the site of Fort Cumberland, in Maryland - which was the limit of the road that had been opened by the Ohio Company. Traversing the country by way of Logstown on the Ohio, below the forks of the river, he with some friendly Indians whom he had engaged to accompany him, pursued the Indian path to Venango. This place, an old Indian town, was the advance post of the French. Here he saw the French flag flying over the log house which had been built by Frazer, but from which he had been ejected. It was now occupied by Joncaire. He was hospitably entertained, and was referred to the Commanding officer whose headquarters were at Le Boeuf, the fort lately built, a short distance above on French creek. Thither Washington went, and was received with courtesy by the officer, Legardeur de Saint-Pierre. To the message of Dinwiddie, Saint-Pierre replied that he would forward it to the Governor-General of Canada; but that, in the meantime, his orders were to hold possession of the country, and this he should do to the best of his ability. With this answer, Washington retraced his steps with Gist, enduring many hardships and passing through many perils, until he presented his report to the Governor at Williamsburg, the 16th of January, 1754.

Washington on his way back, early in January, 1754, at Gist's settlement, (16) met seventeen horses, loaded with materials and stores for a fort at the Forks of the Ohio, and the day after, some families going out to settle. These parties were under the auspices of the Ohio Company, which having imported from London large quantities of goods for the Indian trade, and engaged settlers, had established trading posts at Wills creek, (the New Store), the mouth of Turtle creek, (Frazer's), and elsewhere; had planned their fort at the Forks 0f the Ohio, and were proceeding energetically to the consummation of their designs.

A company of militia was authorized by Virginia early in January, 1754, to co-operate with the Ohio Company in their occupancy. William Trent was commissioned, by Governor Dinwiddie, Captain; John Frazer, who had his trading house at Turtle creek on the Monongahela, after being driven from Venango, was appointed Lieutenant, and Edward Ward was appointed Ensign. (17.)

Trent was then engaged in building a strong log store-house, loop-holed, at Redstone. He was ordered to raise one hundred men. Returning he left Virginia with about forty men intending to have his force recruited by the way. His objective point was the Forks; and he was instructed to aid in finishing the fort, already supposed to have been begun by the Ohio Company. He proceeded to Gist's and thence by the Redstone trail to the mouth of Redstone creek; where after having built the store-house called the Hangard, (18) he proceeded to the Forks of the Ohio, where he arrived on the 17th of February. Here he, with Gist, George Croghan, and others, proceeded shortly to layout the ground and to have some logs squared and laid. Their tenure, however, was of short duration. The Captain having been obliged to go back to Wills creek, across the mountains for provisions, Lieutenant Frazer being absent at Turtle creek at the time, and Ensign Edward Ward in command, the French, under Contrecoeur, April 16th, 1754, suddenly appearing in great force demanded the surrender of the post. (19.) Resistance was out of the question; and on the day following, having surrendered the post, Ward, with his party ascended the Monongahela to Redstone, now Brownsville, where the store-house had been previously erected.

The French, as soon as the season allowed them to begin operations, had come down from Canada in force, and early in the spring had erected a fort at where French creek unites with the Allegheny. This was the third in their series beginning at Lake Erie - Presqu' Isle and Le Boeuf being the other two. This fort was called by the French, Fort Machault, (20) but the English usually referred to it as the French fort at Venango. It was completed in April, 1754, under the immediate superintendence of Captain Joncaire. It was not so large a work as either of the other two, but was suited to the circumstances and for the practical purposes for which it was erected. The object of these forts was not so much to form centres of defensive or aggressive warfare, as to be depots for the stores landed from the lake for transportation to Fort Duquesne which, it was early seen, was to be the real centre of operations. They were not remarkable either for strength or engineering skill; they had no earth-works of importance, and were all of the same plan. The occupants, with the exception of a small garrison, were generally workmen; and this was specially true of Le Boeuf, where canoes and batteaux were prepared for the transportation of troops, munitions and provisions to Fort Duquesne.

This part of the operations of the French was, properly speaking, only the preparation for what they had in view; the real work was to be done at the confluence of the Allegheny and Monongahela rivers. (21.)

The French having duly obtained possession of the Forks of the Ohio, immediately began the erection of a fortification which was strengthened from time to time as danger of an attack increased. It was called Fort Duquesne, in honor of the Governor-General of Canada. (22.)

Orders were despatched from the British cabinet, about this time to the Governors of the Provinces, directing them to resort to force in defense of their rights, and to drive the French from their station on the Ohio.

The King in council, decided that the valley of the Ohio was in the western part of the Colony of Virginia ; and that the march of certain Europeans to erect a fort in parts of his dominions was to be resisted; but the cabinet took no effective measures to support the decree. It only instructed Virginia, by the whole or a part of its militia, at the cost of the Colony itself, to build forts on the Ohio; to keep the Indians in subjection; and to repel and drive out the French by force. A general but less explicit circular was also sent to each one of the colonies, vaguely requiring them to aid each other in repelling all encroachments of France on"the undoubted" territory of England. (23.)

The active operations against the French were thus carried on by the Virginians. The Province of Pennsylvania did not cooperate or in any way assist the Colony of Virginia, although the representatives of the Proprietors always asserted that this region was within the limits of their charter grant.

After Washington returned from his embassy to the French, and had made his report, the utmost activity prevailed in Virginia, and the House of Burgesses, relying on the King to protect the boundary of his dominions, voted means to assist their Governor in carrying on an aggressive campaign.

Washington received from Dinwiddie a commission, first as Major, and shortly after as Lieutenant-Colonel, and was ordered with one hundred and fifty men to take command at the Forks of the Ohio, to finish the fort already begun there by the Ohio Company, and to make prisoners, all or destroy all who interrupted the English settlements. (24.)

While his specific orders were such as we have stated, they had been given prior to the surrender of the post by Ward, and were not applicable to the changed condition of affairs caused by that event.

To more effectively prosecute their campaign, the Virginia Assembly voted an additional sum of money from the public treasury, and the Governor was induced to increase the military force to three hundred men, divided into six companies. Colonel Joshua Fry was appointed to command the whole. With this appointment Washington's commission had been raised to a lieutenant-colonelcy, as stated.

Washington, with his raw recruits raised for this purrose, as soon as the relaxing winter allowed him to move, started from Alexandria, Virginia, April2d, 1754, with two companies of troops, and arrived at Wills creek, (Cumberland), 17th of April, having been joined on his route by a detachment under Captain Stephen. While remaining here for additions to his forces, he learned of the surrender of the fort under Ward to the French. Agreeing at a council of war that it would be unadvisable for them to advance with the prospect of taking the fort without reinforcements, it was resolved to advance to the mouth of Redstone creek on the Monongahela, make a road passable thus far, and there raise a fortification. This point was only 37 miles from the Forks of the Ohio; but the undertaking, with the forces at his command, was one of peril, and its results uncertain and not possible to be foreseen. However, on the 25th of April, 1754, he sent a detachment of 60 men to open a road. The main body of his forces joined this detachment on the lst of May. The road had to be cut as they proceeded, trees felled, rocks removed. Fording deep streams, cutting an opening through the mountains, dragging the few cannon, and while the season was cold and wet, without tents, without a supply of clothes, often in want of Provisions, their progress was thus very slow and toilsome. On the 9th of May, he reached a place called the Little Meadows, (25) which was about one-third the distance to the mouth of Redstone creek, and about half the distance to the place called the Great Meadows. His intention was to reach Redstone, there to take up a strong position, await the arrival of Colonel Fry with reenforcements, and from thence descend the Monongahela to the Forks. Here more than two days were spent in bridging the Little Yough. Having effected a passage through the mountains, he reached, May 18th, the Youghiogheny. This place is called the Great Crossings. They remained here several days, while Washington, with five men in a canoe, descended the river to see if it was navigable. (26.)

His hopes and his voyage ended at the Ohio-Pyle Falls. They crossed this river without bridging, and on May 24th, they arrived at the Great Meadows. (27.) On the morning of that day Washington had received word from Tanacharison, (Half King), the Seneca, his friend, to be on his guard, as the French intended to strike the first English whom they should see. He thereupon hastened to this position. (28.)

That same evening the Half-King's warning was confirmed by a trader, who told him the French were at the crossings of the Youghiogheny. (29.) Washington immediately began to fortify.

On the 27th, Christopher Gist came in from his place, and reported that a detachment of 50 men had been seen at noon the day before, and that he afterwards saw their tracks within five miles of the camp.

Seventy-five men were immediately despatched in pursuit of this party, but they returned without having discovered it, but between 8 and 9 o'clock that night, a messenger came in from Half-King, (Tanacharison), who was then camped with his followers, six miles off, with the report that he had followed the tracks of some Frenchmen to an obscure retreat; and he believed all the party were concealed within a short distance. Fearing a stratagem, Washington put his ammunition in a place of safety; and leaving it under the protection of a strong guard, he set out in the darkness and rain with 40 men, and reached the camp of his friendly Indians late in the night. A council was held. It was agreed that they should march together and attack the enemy in concert; and that to do this they should proceed in single file after the manner of the Indians. Early in the morning they discovered the position of the enemy. A plan of attack was agreed upon: the English occupied what might be called the right wing; the Indians left. He thus advancing came so near the French without being discovered, that the surprise was a success. The French flew to their arms. The firing continued on both sides fifteen minutes. The French were defeated, with the loss of their whole party. Ten men were killed, including Jumonville, their commander, one was wounded; La Force, Drouillon, two cadets, and seventeen others were made prisoners. The Indians scalped the dead. Washington's loss was one killed and two or three wounded. The wing where Washington fought received all the enemy's fire, and it was that part of the line where the one was killed and the others wounded. He was not harmed. This engagement, fought in the darkness of the morning of May 28th, 1754, was the first engagement of war in which Washington took a part. (30.)

The prisoners were marched to the Great Meadows, and from thence conducted over the mountains. Two days after this affair Colonel Fry died at Wills creek. The chief command then devolved on Washington. As soon as the news of the capture of the party under Jumonville reached Fort Duquesne, a strong party was organized to advance against the English. Washington lost no time in enlarging the intrenchment and erecting palisades. This fortification he called Fort Necessity. (31.) With the arrival of Major Muse with the residue of the Virginia regiment, and of Captain Mackay of the Royal army, with his company of 100 men from South Carolina, the force then numbered about 400 men. Leaving Captain Mackay with one company to guard the fort, Washington with the rest pushed over Laurel Hill, cutting the road with extreme labor through the wilderness, to Gist's plantation. (32.) This was about 13 miles distant, and two weeks were consumed in the work. (33.) On June 27th, 70 men under Captain Lewis were detached, and sent forward, to clear the road from Gist's. Ahead of these was another party under Captain Polson, who were to reconnoitre.

During this time there was the greatest activity at Fort Duquesne. On the 28th a force of about 600 French, and some Indians whose numbers were later increased, left that post to confront the English. Washington had knowledge of these things, and on this day a council of war was held at Gist's. It was resolved to have all the forces concentrate at this point, where already some, labor had been expended in throwing up intrenchments. But later news confirming the superiority in number of the enemy, made it apparent that a stand here was inexpedient. The forces all fell back to Fort Necessity. Their private, baggage was left behind, and the horses of the officers were laden with ammunition and public stores - the soldiers of the Virginia regiment dragging their nine swivels by hand over, the rough stony road. The men belonging to the Independent Company looked on, offering no aid, as it was not incumbent on them as King's soldiers to perform such service.

It was not Washington's intention at first to halt but to withdraw to a stronger point and await a re-enforcement. But the men were so exhausted by their labor and from lack of sustaining nourishment, that they could not draw the swivels or carry the baggage on their backs further. They had been eight days without bread. Nor were the supplies of food at Fort Necessity adequate to sustain the march. It was thought best, therefore, to await both supplies and reenforcements. (34.) Hearing of the arrival at Alexandria of two Independent Companies from New York, some days before, it was supposed that they might by this time have reached Wills creek, and an express was despatched to urge them up.

Washington with his party reached the Great Meadows on the 1st of July. The royal troops had done nothing in his absence to make the stockade tenable. He immediately set his men to work to strengthen the fortification. The little intrenchment was a glade between two eminences covered with trees, except within sixty yards of it. On the 3d of July, about noon, seven hundred French, (35) with probably more than one hundred Indians came in sight, and took possession of one of the eminences. The rising ground was covered with large trees. These offered shelter to the assailants, and from behind them they could fire in security on the troops beneath. A heavy rain set in. The engagement continued till nightwhen De Villiers, fearing his ammunition would give out, proposed a parley. The terms of capitulation that were offered were interpreted to Washington, who did not understand French; and as interpreted were accepted. The next day being the fourth of July, a date which afterward became the most famous in the annals of American history, the English surrendered. By the articles agreed to, they were allowed to retire without insult or outrage from the French or Indians; and to take with them their baggage or stores, except artillery.

At day-break the garrison filed out of the fort, with colors flying, and drums beating, and one swivel gun. The English flag on the fort was struck, and the French flag took its place; and when the little army of Washington had passed over the mountains homeward, the lilies of France floated over every fort, military post and mission from the Alleghenies westward to the Mississippi.

______

Notes to Introduction.

(1.) In the year 1748, Thomas Lee, one of his Majesty's Council in Virginia, formed the design of effecting settlements on the wild lands west of the Allegheny mountains, through the agency of an association of gentlemen. Before this date there were no English residents in those regions. A few traders wandered from tribe to tribe, and dwelt among the Indians, but they neither cultivated nor occupied the lands. With the view of carrying his plan into operation, Mr. Lee associated himself with twelve other persons in Virginia and Maryland, and with Mr. Hanbury, a merchant in London, who formed what they called "The Ohio Company." Lawrence Washington, and his brother Augustine Washington, (two brothers of George Washington), were among the first who engaged in this scheme. A petition was presented to the King in behalf of the Company, which was approved, and five hundred thousand acres of land were granted almost on the terms requested by the Company.

The object of the Company was to settle the lands and to carry on the Indian trade on a large scale. Hitherto the trade with the Western Indians had been mostly in the hands of the Pennsylvanians. The Company conceived that they might derive an important advantage over their competitors in this trade from the water communications of the Potomac and the eastern branches of the Ohio, whose head-waters approximated each other. The lands were to be chiefly taken on the south side of the Ohio, between the Monongahela and Kenawha and west of the Alleghenies. The privilege was reserved, however, by the Company of embracing a portion of the lands on the north side of the river, if it should be deemed expedient. Two hundred thousand acres were to be selected immediately, and to be held for ten years free from quit-rent or any tax to the King, on condition that the Company should at their own expense seat one hundred families on the lands within seven years, and build a fort and maintain a garrison sufficient to protect the settlement. [Spark's Washington. - Appendix.]

The interests of this Company were subsequently merged in other companies. All persons concerned were losers to a considerable amount.

(2.) "As early as the winter of 1669-70 or in the spring of the latter year, Robert Chevalier de la Salle, penetrated to the upper waters of the Allegheny, and descending that stream and the Ohio as far as the falls, where the City of Louisville, Kentucky, now stands, returned. But he has left only the merest reference to this expedition in his writings, so that for a time many denied it altogether, though later investigations have placed it beyond reasonable doubt. But an impassable barrier yet existed to the safe travel and explorations of these parts, in the fierce and treacherous Iroquois or "Five Nations," who were the terror of both the French and Indians from the mouth of the St. Lawrence to the banks of the Mississippi."

So well known an explorer as La Salle needs but a short notice. Robert Chevalier de la Salle was born in Rouen, France, in November, 1643. He was a short time with the Jesuits, but withdrew, and came to Canada in 1666, from which time his life was given to exploring the Great Lakes and the Mississippi with its tributaries, till he was killed in Texas, March 19, 1687. For an estimate of his character and qualities see Parkman's La Salle pp. 406, 407; also Charlevoix Vol. iv, pp. 94-95. [Register of Fort Duquesne; translated from the French, with an Introductory Essay and Notes by Rev. A. A. Lambing, A. M.

Throughout this Introduction wherever it has been necessary to make reference to authorities or quote relevant matter, use has been made of the Register. Rev. Lambing in his Introductory Essay and Notes quotes numerous authorities, and as he has greatly abridged the biographical notices therein, they have been of much use to us here.

(3.) Poland Michael Barrin, Marquis de la Galissoniere, was born at Rochfort, France, Nov. 11,1693; rose through different grades to that of admiral; was appointed Governor-General of Canada in 1747 - that province being under the management of the Marine Department, - was energetic in maintaining the interests of France; returned to his native land late in 1749; and died at Nemour, Oct. 26th, 1756.

(4.) Celoron de Bienville. - This officer must not be confounded, as is sometimes done, with another officer, Captain Celoron de Blainville. From 1739 to 1741 he had charge of various expeditions and missions in the extreme northwest about Michilimackinac (Mackinack.) Soon after, he was in command at Detroit; he was sent in October, 1744, to command at

Fort Niagara. In June, 1747, he is spoken of as commander at Fort St. Frederic on Lake Champlain, but was relieved in November, and was despatched to Detroit with a convoy, in May, 1748, from which he returned in September. He was then trusted with the expedition down the Ohio. In the summer of 1750 he was commander at Detroit, and five years later was again at Fort St. Frederic. His chaplain, Father Bounecamp, speaks of him as fearless, energetic and full of resources; but the Governor calls him haughty and insubordinate.(5.) "In the present Register, the officer here mentioned is called 'Monsieur Pierre Claude de Contrecoeur, Esquire, Sieur de Vaudry, Captain of Infantry, Commander-in-Chief of the Forts of Duquesne, Presqu' Isle and the Reviere Au Boeufs.' He was in command of Fort Niagara at the time of which we are now speaking; but he afterward succeeded to the command of the detachment which had before belonged to M. Saint Pierre. Whether he was in command of the fort at the time of the battle of the Monongahela (Braddock's Defeat), July 9th, 1755, is disputed. See also registry of the interment of Sieur de Beaujeur further on. The last day on which the name of Contracoeur is found in the Register is March 2, 1755; and the first appearance of that of M. Dumas is, Sept. 18th, of the same year. The number of entries in the Register is so few, indeed, that they cannot be taken as an authority in fixing dates with precision; but where a name is mentioned it is always a high authority. What became of M. Contrecoeur after his retiring from Fort Duquesne, I have not been able to learn." [Register, p. 15 n.]

Note by Rev. A. A. Lambing, to the Register. - "I have retained the title 'Sieur,' not finding its exact equivalent in our language, It is sometimes translated 'Sire,' but whatever may have been the derivation or the original meaning of that term, its present signification forbids such a use of it."

(6.) There were seven brothers of his family, six of whom lost their lives in the American wars. This one commanded an expedition against Fort Necessity in June, 1754. He was afterwards taken prisoner by the English at the capture of Fort Niagara.

(7.) Of the elder Joncaire, the father of the one referred to in this place, see interesting particulars in Mr. Parkman's Frontenac. He died in 1740, leaving two sons, Chabert Joncaire, and Philip Clauzonne Joncaire, both of whom were in the French service and were in Celoron's expedition. The one who took the most prominent part was Chabert de Joncaire, or Joncaire-Chabert. He was on the Allegheny for the next two years at least, and was at Logstown on May 18th, 1751. Both were taken prisoners at the capture of Fort Niagara. The name is variously spelled by early writers as John Coeur, Jean Coeur, Joncoeur, Joncaire, etc.

He acted officially as interpreter between the French and Indians. He was adopted by the Senecas, and had great influence and power over them.

(8.) Near the village of Barcelona, New York.

(9.) These plates were about eleven inches long, seven and one-half inches wide, and one-eighth of an inch thick. For the inscription of the one which was buried at the Forks of the Ohio, see notes to Fort Duquesne.

Both Celoron and his Chaplain; Father Bonnecamp, a Jesuit, kept journals of the expedition, and the latter also drew a map, which is remarkably accurate considering the circumstances. He also took the latitudes and longitudes of the principal points. This map is frequently referred to, as it marks the location of the various tribes and as it gives the Indian names of the streams and of their villages, Father Bonnecamp's map is here reproduced.

(10.) Joncaire in May, 1751, held a council with the Indians at Logstown, but could not induce them to let the French have possession of their lands.

In August, 1749, Governor Hamilton, who had arrived at Philadelphia in November, 1748, sent George Croghan to the Ohio with a message to the Indians, to notify them of the cessation of hostilities between Great Britain and France and to inquire of them the reason of the march of Celoron through their country. In the report of his transactions (Second Arch. vi, 516) it is related that the Indian tribes on the Ohio and its branches, on this side of Lake Erie, were in strict friendship with the English and with the several provinces, and took the greatest care to preserve the friendship then subsisting between them and the English. At that time, he says "We carried on a considerable branch of trade with those Indians for skins and furs, no less advantageous to them than to us."

In April, 1751, the Governor again sent Croghan to the Ohio with a present of goods. In one of the speeches made on the part of the Indians the wish was warmly expressed that the Governor of Pennsylvania would build a fort on the Ohio, to protect the Indians as well as the English traders, from the insults of the French. On the 12th of June, 1752, the Virginia Commissioners who met the Indians at Logstown were requested, even insisted upon, to have their government build a fort at the forks at the same place where they had requested the Pennsylvanians to build one.

(11.) History of Erie County, by Laura G. Sanford * * * Many of these details are given in the Introduction to the Register, by Rev. Father Lambing.

(12.) See Fort Presqu' Isle.

(13.) See Fort LeBoeuf.

(14.) Deposition of Stephen Coffen. (Second Arch., vi, 184.)

(15.) Gist was the Ohio Company's agent to select the lands and conciliate the Indians. In 1750, Gist, as the Company's surveyor, carried chain and compass down the Ohio as far as the falls at Louisville.

(16.) Washington calls this "at Mr. Gist's, at Monongahela." To this Mr. Veech remarks: "The reader must understand, that at this early day, Monongahela was a locality which covered an ample scope of territory. Gist's Plantation, was about sixteen miles from the river, which, when Washington wrote this he had never seen." - The Monongahela of Old,

p. 340. n.(17.) This Company was one of two authorized by Virginia. Washington was Major of the two, and remained behind organizing his force. Trent was Captain of one of these companies.

(18.) Hangard, literally, "storehouse."

(19.) "With the opening of spring, they were in the field, and, having completed Fort Machault, they descended the Allegheny in a fleet of canoes and batteaux, to the number, variously estimated, but perhaps little less than one thousand French, Canadians and Indians, with eighteen cannon in command of Contrecoeur."-Rev. A. A. Lambing, in Register, p.24.

"The French flotilla of 300 canoes and 60 batteaux, with 1,400 soldiers and Indians, and 18 cannon." - Wm. M. Darlington; Esq., in Centenary Memorial.

Washington's account agrees with this, only he says "upwards of 1,000 men." Col. Washington to the Governors of Virginia and Penna., 25th April, 1754. Authorities vary as to the number of men in Ward's command. It is mostly put at forty. Bancroft's Hist. U. S., iii. 75, says the force was "only 33 in number." Will. M. Darlington, in Centenary Memorial, p. 240, says, "Ward having but 41 men, of whom only 33 were soldiers, Ward surrendered the fort." Sparks' Washington, Vol. ii, p. 4, says, The whole number of his men was forty-one."

On the 25th of August, 1753, Trent had viewed the ground in the forks on which to build a fort, it being considered preferable to the location at the mouth of Chartiers creek, as originally intended by the Ohio Company.

Ward hearing of the French descending the river on the 13th of April, (1754), he hastened to complete the stockading of the building, and had the last gate finished when the French were seen approaching on the river. - Wm. M. Darlington, Centenary Memorial, 259. See Fort Duquesne.(20.) See Fort Machault.

(21.) Register of Fort Duquesne, p. 23, and citations there.

(22.) See Fort Duquesne.

(23.) Bancroft Hist. U. S., iii, 73. (Cent. Edition.)

(24.) These are the words of his commission. Officers and men were encouraged by the promise of a royal grant of two hundred thousand acres on the Ohio to be divided amongst them * * * Of the two companies to be raised by Virginia, Capt. Trent was to raise one and Washington the other. Washington was Major and ranking officer. The force was to consist of two hundred men.

(25.) Mention of the Little Meadows is frequently made in connection with the affairs in this region down to the defeat of Braddock. Its location with respect to the other posts on the line of the route was such as to make it an objective and noticeable point. It was about twenty miles west of Fort Cumberland. When Braddock came out on this route, he dispatched Sir John Sinclair and Major Ohapman (on the 27th of May, 1755), ahead of the main body of the army to build a fort here. The army was seven days in reaching this place from Cumberland.

At the Little Meadows a division of the army was made; the General and Col. Halket, with select portions of the two regiments, and the other forces, lightly encumbered; going on in advance, being in all about 1,400. Col. Dunbar, with the residue, about 850, and the heavy baggage, artillery and stores, were left to move up by slow and easy marches. Here Washington, stricken down by a fever, was left by Braddock, under the care of his friend Dr. Craik and a guard, two days in advance of Dunbar, to come on with him if able; the gallant aid requiring from the General a solemn pledge not to arrive at the French fort until he should join him. Washington did not report himself until the day before the battle. [The Monongahela of Old, p. 58, et. seq.]

(26.) "On the 18th they arrived at the Great Crossings, and remained there several days, while Washington, with five men in a canoe, descended the river to ascertain if it was navigable. His hopes and his voyage ended at the Ohio-Pyle Falls. They crossed the river without bridging." [The Mon. of Old, p. 43.]

(27.) The location subsequently of Fort Necessity.

(28.) The French had it reported that this force was sent out to hunt deserters. During this march, Washington had reports almost daily from scouts, traders, Indians and deserters as to the movements of the enemy.

(29.) The Crossings of the Youghiogheny were afterward known as Stewart's Crossings from the circumstance of one William Stewart's living near the place in the year 1753 and part of 1754, he having been obliged finally to leave the country on account of the French taking possession of it. It was the place where Braddock's army crossed.

(30.) See Jumonville's Camp.

(31.) See Fort Necessity.

(32.) Near the town of Connellsville, Fayette county, Pa, Christopher Gist's house was thirteen miles from the Great Meadows, not far from Stewart's Crossings on the Youghiogheny river; five or six miles from Dunbar's camp.

(33.) As Capt. Mackay bore a king's commission, he would not receive orders from the provincial colonel. He encamped apart from the Virginia troops. Neither would his men do work on the road. To prevent mutiny and a conflict of authority, Washington concluded to leave the royal captain and his company to guard the fort and stores, while he, on the

16th, set out with his Virginia troops, the swivels, some wagons, etc., for Redstone, making the road as he went. [The Monongahela of Old, 848.](34.) They had milch cows for beef, but no salt to season it. Besides the "chopped flour" which they found at the fort, there were some provisions from the "settlements," but only enough for four or five days. When the French came up they killed all the horses and cattle.

In the sketch of Wendel Brown and his sons, given by Mr. Veech, he says that they were the first white settlers within the limits of Fayette county, having come there as early as 1750 and '51, when the country was an unbroken wilderness. They came from Virginia. "When Washington's little army was at the Great Meadows, or Fort Necessity, the Browns packed provisions to him - corn and beef. And when he surrendered on the 4th of July, 1754, they retired, with the retreating colonial troops across the mountains. [Mon. of Old, p.209.]

The Indians friendly to Washington, such as Half-King, (Tanacharison), and Queen Alliquippa and her son, and their people who took part with the English, crowded into the fort bringing with them their squaws and children. These became consumers of the scanty supplies without being of any relative advantage, thus adding to the complexities of the occasion. They were afraid to return to their homes after the success of the French. Some went back later, but others never returned to their lodges about the Ohio.

(35.) The number here, as in all like engagements, varies in different authorities. Bancroft: Hist. U. S., iii, p. 78, says 600 French with 100 Indians * * * * Sparks's Washington : "the whole body of the enemy by report amounted to 900 men." * * * * The number given above is from the French account.

Washington's loss in this action out of the Virginia regiment, was twelve killled and forty-three wounded. Capt. Mackay's losses were never reported.

The following extracts are taken from the "Papers relating to the French Occupation," and the events are reported from their point of view. "The English having, in 1754, built Fort Necessity, twenty-five leagues [?] from Fort Duquesne, M. de Jumonville was detached with 40 men to go and summon the garrison to retire. He was killed with seven Canadians, and the remainder of his detachment made prisoners of war. On this intelligence, Captain de Villiers, of the troops of the Marine, was ordered to conduct 700 men and avenge his brother's death; he reduced said fort on the 3d of July by capitulation, and made the garrison prisoners of war." [Second Arch., vi, 439.]

M. Varin to M. Bigot, from Montreal, the 24th of July, 1754, "M. de Villiers had 700 men with him, 600 of whom are French, and 100 Indians, who attacked Fort Necessity in broad day." [Second Arch., vi, 168.]

Extract from M. de Villiers' Journal annexed to M. Varin's letter. "The enemy's fire increased toward six o'clock in the evening with more vigor than ever, and lasted until eight. * * * The English had seventy to eighty [?] men killed or mortally wounded, and many others slightly. The Canadians have had two men killed, Desprez, Junior and the Panis, belonging to M. Pean, and seventy wounded, two whereof are Indians." - This report, as is usual with the French reports from this quarter, is greatly exaggerated in their own behalf.

JUMONVILLE'S CAMP .Pages 23-26

Washington reached Wills creek with three companies, on the 20th of April, 1754, and two days after Ensign Ward arrived with the intelligence of the surrender of the works at the Forks of the Ohio. Washington immediately sent expresses to the Governors of Pennsylvania, Maryland and Virginia, asking for reenforcements, and then after a consultation with his brother officers, resolved to advance, and, if possible, to reach the Monongahela, near where Brownsville now stands, and there erect a fortification. On the 9th of May, he was at Little Meadows, and there received information that Contrecoeur had been reenforced with eight hundred men. On the 18th, he was encamped on the Youghiogheny, near where Smithfield, in Fayette county, now stands. From that point, he,with Lieutenant West, three soldiers, and an Indian, descended the river about thirty miles, hoping to find it navigable, so that he could transport his cannon in canoes, but was disappointed. He had scarcely returned to his troops, when a messenger from his old friend Tanacharison arrived, with information that the French were marching toward him, with a determination to attack him. The same day he received further information that the enemy were at the crossings of the Youghiogheny, near where Connellsville now stands, about eighteen miles from his own encampment. He then hurried to the Great Meadows, where he made an intrenchment, and by clearing away the bushes prepared a fine field for an encounter. Next day Gist, his old pilot, who resided near the crossings, arrived with the news that a French detachment of fifty men had been at his place the day before.

That same night (May 27th), about nine o'clock, an express arrived from Tanacharison, who was then encamped with some of his warriors about six miles off, with information that the French were near his encampment. Col. Washington, says Sparks, immediately started with forty men to join the Half-King. The night was dark, the rain fell in torrents, the woodswere intricate, the soldiers often lost their way groping in the bushes and clambering over rocks and logs, but at length they arrived at the Indian camp just before sunrise (May 28th). A council with Tanacharison was immediately held, and joint operations against the French were determined on. Two Indian spies discovered the enemy's position in an obscure place, surrounded by rocks, and a half mile from the road. Washington was to advance on the right, Tanacharison on the left. Thus they approached in single file, until they were discovered by the French who immediately seized their arms and prepared for action, which was commenced by a brisk firing 0n both sides, and which was kept up for a quarter of an hour, when the French ceased to resist. Monsieur Jumonville, the commandant, and ten of his men were killed, and twenty-two were taken prisoners, one of whom was wounded. A Canadian escaped during the action. Washington had one man killed and two wounded. No harm happened the Indians. The prisoners were sent to Governor Dinwiddie.

The affair was misrepresented greatly to the injury of Washington. War had not yet been declared, and it was the policy of each nation to exaggerate the proceedings of the other. Hence it was officially stated by the French Government that Jumonville was waylaid and assassinated, while bearing a peaceful message to Washington."Jumonville's camp," says Mr. Veech in Monongahela of Old, "is a place well known in our Mountains. It is near half a mile southward of Dunbar's Camp, and about five hundred yards eastward of Braddock's Road - the same which Washington was then making. The Half-King's Camp was about two miles further south near a fine spring, since called Washington's Spring, about fifty rods northward of the Great Rock.

"The Half-King discovered Jumonville's, or La Force's Camp by the smoke which rose from it, and by the tracks of two of the party who were out on a scouting excursion. Crawling stealthily through the laurel thicket which surmounts the wall of rock twenty feet high, he looked down upon their bark huts or "lean-tos ;" and, retreating with like Indian quietness, he immediately gave Washington the alarm. There is not above ground, in Fayette county, a place so well calculated for concealment, and for secretly watching and counting Washington's little army as it would pass along the road, as this same Jumonville's Camp,"

"It may not be possible to ascertain at this time the precise object for which the party under Jumonville was sent out. The tenor of his instructions, and the manner in which he approached Colonel Washington's camp, make it evident that he deviated widely from the mode usually adopted in conveying a summons; and his conduct was unquestionably such as to create just suspicions, if not to afford a demonstration of his hostile designs. His appearance on the route at the head of an armed force, his subsequent concealment at a distance from the road, his remaining there for nearly three days, his sending off messengers to M. de Contrecoeur, were all circumstances unfavorable to pacific purposes. If he came really as a peaceful messenger, and if any fault was committed by the attack upon him, it must be ascribed to his own imprudence and injudicious mode of conducting his enterprise, and not to any deviation from strict military rules on the part of Colonel Washington, who did no more than execute the duty of a vigilant officer, for which he received the unqualified approbation of his superiors and of the public."

The following from Evert's History of Fayette County describes the location about 1881 :

"Jumonville's Camp is nearly half a mile south of Dunbar's Camp, and 500 yards east of the old Braddock Road. One quarter of a mile south of Dunbar's Camp is Dunbar's Spring, and nearly one-quarter of a mile down the run from the spring, about ten feet from the right bank, is the spot supposed to be Jumonville's grave; then west about 20 yards in a straight line is the camp, half-way along and directly under a ledge of rocks 20 feet high and covered with laurel, extending in the shape of a half-moon half a mile in length in the hill and sinking as it approaches, and dipping into the earth just before it reaches Dunbar's Spring. Thus situated in the head of a deep hollow, the camp was almost entirely concealed from observation. * * * The location is in Wharton township, Fayette county." [History of Fayette County, p. 829.]

FORT NECESSITY.

Pages 26-39.

The discomfiture of La Force's party, and the death of Jumonville, were immediately heralded to Contrecoeur at Fort Duquesne by a frightened, barefooted fugitive Canadian. Vengeance was vowed at once, but it was not yet quite ready, to be executed. Washington, however, knowing the impressions which this, his first encounter, would make upon the enemy, at once set about strengthening his defences. He sent back for reenforcements, and had his fort at the Meadows palisaded and otherwise improved. And, to increase his anxieties, the friendly Indians, with their families, and several deserters from the French, flocked round his camp, to hasten the reduction of his little store of provisions. Further embarrassments awaited him.

On the 9th of June, Major Muse came up with the residue of the Virginia regiment, the swivels and some ammunition; but it was now ascertained that the two Independent Companies from New York, and the one from North Carolina, that were promised, would fail to arrive until too late. The latter only reached Cumberland after the surrender; while the fixed antipathies to war and the proprietary prerogative, of the Pennsylvania Assembly, had rendered all Governor Hamilton's entreaties for aid from that Province ineffectual. In his extremity, Colonel Washington displayed the same energy and prudence that carried him so successfully through the dangers and disappointments of the Revolution. He hired horses to go back to Wills creek for more balls and provisions, and induced Mr. Gist to endeavor to have the artillery, &c., hauled out by Pennsylvania teams - the reliance upon Southern promises of transport having failed, as it did with Braddock. But no artillery came in time; ten only, of the thirty-four pound cannon and carriages, which had been sent from England, having been forwarded to Wills creek, but too late. Washington also took active measures to have a rendezvous at Redstone, of friendly Indians from Logstown and elsewhere below Duquesne; but in this he failed.

On the next day (the 10th), Captain Mackay came up with the South Carolina company; but as he bore a king's commission, he would not receive orders from the provincial colonel, and encamped separate from the Virginia troops; neither would his men do work on the road. To prevent mutiny, and a conflict of authority, Colonel Washington concluded to leave the royal captain and his company to guard the fort, and stores, while he, on the 16th, set out with his Virginia troops, the swivels, some wagons, &c., for Redstone, making the road as he went. So difficult was this labor over Laurel Hill, that two weeks were spent in reaching Gist's, a distance of thirteen miles.

On the 27th of June, Washington detached a party of some seventy men under Captain Lewis, to endeavor to clear a road from Gist's to the mouth of Redstone; and another party under Captain Polson, was sent ahead to reconnoitre. Meanwhile Washington completed his movements to Gist's.

The French, in the meantime, were active, and on the 28th a strong force left Fort Duquesne to attack Washington. It consisted of five hundred French, and some Indians, afterwards augmented to about four hundred. The commander was M. Coulon de Villiers, half brother of Jumonville, who sought the command from Contrecoeur as a special favor, to enable him to avenge his kinsman's "assassination." They went up the Monongahela in periaguas (big canoes), and on the 30th came to the Hangard at the mouth of Redstone, and encamped on rising ground "about two musket shot from it." This Hangard (built the last winter, as our readers will recollect, by Captain Trent, as a store house for the Ohio Company), is described by M. de Villiers as a "sort of fort built with logs, one upon another, well notched in, about thirty feet long and twenty feet wide." Veech says (1858), "It stood near where Baily's mill now is."

Hearing that the object of his pursuit were intrenching themselves at Gist's, M. de Villiers disencumbered himself of all his heavy stores at the Hangard; and, leaving a sergeant and a few men to guard them and the periaguas, rushed on in the night, cheered by the hope that he was about to achieve a brilliant coup de main upon the young "buckskin Colonel." Coming to the "plantation" on the morning of July 2d, the gray dawn revealed the rude half-finished fort, which Washington had there begun to erect. This, the French at once invested, and gave a general fire. There was no response; the prey had escaped. Foiled and chagrined, Villiers was about to retrace his steps, when a half-starved deserter from the Great Meadows came in, and disclosed to him the whereabouts and destitute condition of Washington's forces. Having made a prisoner of the messenger, with a promise to reward, or to hang him, according as his tale should prove true or false, the French commander resolved to continue the pursuit. Upon this we leave him, while we post up Colonel Washington's movements.

Hearing the French approach, Washington, being at Gist's on the 29th, began throwing up intrenchments, with a view to make a stand there. He called in the detachments under Captains Lewis and Polson, and sent back for Captain Mackay and his company. These all came, and upon council held it was determined to retreat. The imperfect intrenchment was abandoned, and sundry tools and other articles concealed, or left as useless. The lines of this old fortification have been long obliterated, but its position is known by the numerous relics which have been ploughed up. It was, according to Veech, near Gist's Indian hut and spring, about thirty rods east of Jacob Murphy's barn, and within fifty rods of the centre of Fayette county.

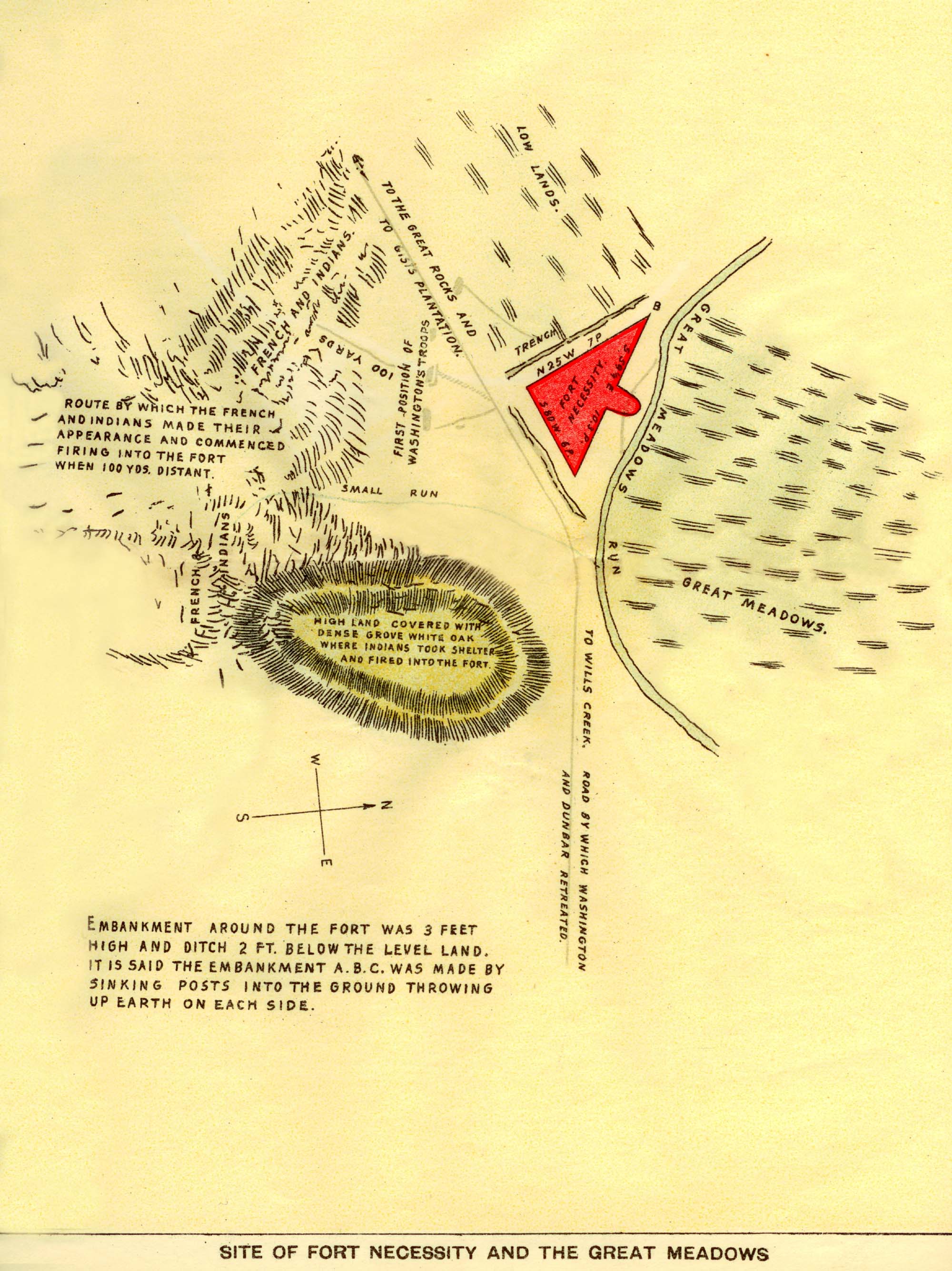

The retreat was begun with a purpose to continue it to Wills creek, but it ended at the Meadows. Thither the swivels were brought back, and under the additional advice and supervision of Capt. Stobo, a ditch and additional dimensions and strength were given to the fort, now named "Fort Necessity." So toilsome was this hasty retreat, there being but two poor teams, and a few equally poor pack horses - that Washington and other officers had to lend their horses to bear burdens, and to hire the men to carry and drag the heavy guns. Captain Mackay's company was too royal to labor in this service, and the Virginians had to do it all. When they reached the Meadows on the 1st of July, their fatigue was excessive. The had had no bread for eight days; they had milch cows for beef, but no salt to season it. Arrived at the fort, they found some relief in a few bags of chopped flour and other provisions from the "settlements," but only enough for four or five days. Thus fortified and provisioned, they hoped to hold out until reenforcements arrived, but they came not.

After a rainy night, early on the morning of July 3d, the enemy approached, strong in numbers and confidence, but fortunately without artillery. A wounded scout announced their approach. The French delivered the first fire of musketry from the woods, at a distance of some four or five hundred yards, doing no harm. Washington formed his men in the Meadow outside the fort, wishing to draw the enemy into an open encounter. Failing in this, he retired behind his lines, and, after irregular ineffective firing during the day, and until after dark, the French commander asked a parley, which Washington at first declined, but when asked again, granted. In this he behaved with singular caution and coolness; anxious lest his almost total destitution of ammunition and provisions should be discovered, yet betraying no fear or precipitation. The French and Indians had killed or stolen all his horses and cattle, and thus his means of retreat were rendered as meagre as his means of defence. Yet with all these disadvantages, in numbers and resources, he obtained terms of surrender, highly honorable and liberal. Indeed, the French commander seems to have been a very fair sort of man. The articles of capitulation were drawn and presented by him in the French language; and after sundry modifications in Washington's favor, were signed in duplicate, amid torrents of rain, by the dim light of a candle, by Captain Mackay, Colonel Washington, and M. de Villiers.

The French commander professed to have no other purpose than to avenge Jumonville's "assassination" and to prevent any "establishment" by the English upon the French dominions. Hence, the articles of capitulation agreed on allowed the English forces to retire without insult or outrage from the French or Indians, to take with them all their baggage and stores, except artillery , the English colors to be struck at once; and at day-break next morning (July4th), the garrison was to file out of the fort and march with colors flying, drums beating, and one swivel gun. They were also allowed to conceal such of their effects, as by reason of the loss of their oxen and horses they could not take with them, and to return for them thereafter, upon condition that they should not again attempt any establishment there, or elsewhere west of the mountains. The English were to return to Fort Duquesne the officers and cadets taken at the "assassination" of Jumonville, as hostages, for which stipulation Captains Van Braam and Stobo were given up to the French, as we have before related.

Such were, in substance, the terms of the surrender of "Fort Necessity." But so powerless in all the physicale of military movements had Washington become, that nothing could be carried off but the arms of the men, and what little of other articles was indispensable for their march to Wills creek. Even the wounded and sick had to be carried by their fellows. All the swivels were left. These were the "artillery," which the French required to be given up. It is said that Washington got the French commander to agree to destroy them. This was not done as to some of them - perhaps they were only spiked; for in long after years, emigrants found and used several of them there. Eventually they were carried off to Kentucky to aid in protecting the settlers of the "bloody ground."

The French took possession of the fort, and demolished it on the morning of the 4th of July, a day afterwards to become as gloriously memorable in the recollection of Washington, as now it was gloomy.

Washington's loss in the action, out of the Virginia regiment, was twelve killed and forty-three wounded. Capt. Mackay's losses were never reported. The French say they lost three killed and seventeen wounded.

The French, apprehensive that the long expected reenforcements to Washington might come upon them hastily, retired from the scene on the same day, marching "two leagues," or about six miles. On the 5th they passed Washington's abandoned intrenchment at Gist's, after demolishing it and burning all the contiguous houses. At 10 a. m. next day, they reached the mouth of Redstone, and after burning the Hangard, re-embarked on the placid Monongahela. On the 7th they accomplished their triumphant return to Fort Duquesne, "having burnt down," says M. de Villiers, in his Journal, "all the settlements they found."

Washington returned, sadly and slowly, to Wills creek, and thence to Alexandria.

The site of Fort Necessity was the Great Meadows. James Veech, in The Monongahela of Old, gives in detail, as the result of his personal investigation, the following:

"The engraving and description of 'Fort Necessity' given in Sparks' Washington are inaccurate. It may have presented that diamond shape, in 1830. But in 1816, the senior author of these sketches made a regular survey of it, with compass and chain. The accompanying sketch exhibits its form and proportions, (1.) As thereby shown, it was in the form of an obtuse angled triangle of 105 degrees, having its base or hypothenuse upon the run. The line of the base was, about midway, sected or broken, and about two perches of it thrown across the run, connecting with the base by lines of the triangle. One line of the angle was six, the other seven perches; the base line eleven perches long, including the section thrown across the run. The lines embraced in all about fifty square perches of land, on nearly one-third of an acre. The embankment then (1816), was nearly three feet above the level of the Meadow. The outside "trenches," in which Captain Mackay's men were stationed when the fight began, (but from which they were flooded out), were filled up. But inside the lines were ditches or excavations, about two feet deep, formed by throwing the earth up against the palisades. There were no traces of "bastions," at the angles or entrances. The junctions of the Meadow, or glade, with the wooded upland, were distant from the fort on the southeast about eighty yards, on the north about two hundred yards, and on the south about two hundred and fifty. Northwestward in the direction of the Turnpike road, the slope was a very regular and gradual rise to the high ground, which is about four hundred yards distant. From this eminence the enemy began the attack, but afterward took position on the east and southeast nearer the fort. One or two field pieces skillfully aimed and fired would have made short work of it.

" A more inexplicable, and much more inexcusable error than that in Mr. Sparks' great work, is the statement of Colonel Burd, in the Journal of his expedition to Redstone, in 1759. He says the fort was round, with a house in it. That Washington may have bad some sort of a log, bark-covered cabin erected within his lines, is not improbable; but how the good Lancaster Colonel could metamorphose the lines into a circular form is a mystery which we cannot solve.

"The site of this renowned fort is well known. Its ruins are yet, (1858), visible. It stands on Great Meadow run, which empties into the Youghiogheny. The "Great Meadows," with which its name associates in history, was a large natural meadow or glade, now highly cultivated and improved. The place is now better known by the name of "Mount Washington,"on the National Road, ten miles east of Uniontown, Fayette county, the old fort being about three hundred years southward of the brick mansion or tavern house. In by-gone days thousands of travelers have stopped here, or rushed by, without a thought of its being or history; while a few have thrown a reverential glance upon the classic spot. Washington in all his after life, seems to have loved the place. As early as 1769 he acquired from Virginia a pre-emption right to the tract of land (234) acres, which includes the fort; the title to which was afterwards confirmed to him by Pennsylvania. It is referred to in his last will, and he owned it at his death. His executors sold it to Andrew Parks of Baltimore, whose wife, Harriet, was a relative and legatee "of the General. She sold it to the late General Thomas Mason, who sold it to Joseph Huston, as whose property it was bought at sheriff's sale by Judge Ewing, who sold it to the late James Sampey, Esq., whose heirs have recently sold it to a Mr. Facenbaker. An ineffectual effort was made some years ago to erect a monument upon the site. The first battle ground of Washington surely deserves a worthier mark of commemoration than mouldering embankments surmounted by a few decaying bushes."

In reference to the project of erecting a monument spoken of by Mr. Veech above, there is this further information: "On July the 3d, 1854, the corner-stone for a monument was laid with appropriate ceremonies and speeches, by citizens from different places. A handsome view of the surrounding neighborhood, painted by Paul Weber, taken in July, 1854, ornaments the wall of the Historical Society of Pennsylvania, at Philadelphia. The following extract of a letter from Townsend Ward, who with others, was a visitor at the same time with Weber, and printed in the North American of July 3rd, 1854, furnishes a description of the present (then) condition of the fort and country around :

"Fort Necessity is four miles east of Laurel Hill, and about three hundred yards south of the National Road. As we approached the spot, the star-spangled banner floated from its staff, as if in honor of our pilgrimage. The meadow or glade is entirely level - the rising ground approaching the site of the fort one hundred yards on one side, and about one hundred and fifty on the other. Braddock's Road skirts the rising ground to the south. A faint out-line of the breast-work, and a trace of the ditch are yet visible, and now will remain so, for the rude hand which held the plow that aided during many years to level them, was stayed at the intercession of a lover of the memories of these old places. The creek was dry, and this is all that remains. The artillery which Washington was unable to remove, remained a number of years, and it is said to have been the custom of emigrants who encamped at fort to use it in firing salutes. At length the pieces, one by one, were carried to Kentucky by some of the emigrants who crossed the mountains."

Sparks' description of the place follows:

"The space of the ground called the Great Meadows, is a level bottom, through which passes a small creek, and is surrounded by hills of a moderate and gradual ascent. This bottom, or glade is entirely level, covered with long grass and small bushes, and varies in width. At a point where the fort stood, it is about two hundred and fifty yards wide, from the base of the one hill to that of the opposite. The position of the fort was well chosen, being about one hundred yards from the upland, or wooded ground, on the one side, and one hundred and fifty on the other, and so situated on the margin of the creek, as to afford easy access to water. At one point, the high ground comes within sixty yards of the fort, and this was the nearest distance to which an enemy could approach under the shelter of trees. The outlines of the fort were still visible, when the spot was visited by the writer in 1830, occupying an irregular square, the dimensions of which were about one hundred feet on each side. One of these was prolonged further than the other, for the purpose of reaching the water m the creek. On the west side, next to the nearest wood, were three entrances, protected by short breast-works or bastions. The remains of a ditch, stretched round the south and west sides, were also distinctly seen. The site of this fort is three or four hundred yards south of what is called National Road, four miles from the foot of Laurel Hill and fifty miles from Cumberland or Wills Creek."

Notes to Fort Necessity.

(1.) The exhibits referred to have never been printed. Mr. Veech compiled his Monongahela of Old prior to 1858. A part of it had been published by him in newspapers, but the work itself was printed in sheets which were not bound or put in book form until 1892 - then after Mr. Veech's death, and without any alteration. A part of the work - pages 241 and 259 - was included in a pamphlet issued in 1857, entitled "Mason and Dixon's line." The edition of 1892 was "for private distribution only." As Mr. Veech was a skilled surveyor and draughtsman, it is much to be regretted that the exhibits are not available.(2.) "When Washington first camped at the Great Meadows, he had about one hundred and fifty men, soon after increased to three hundred, in six different companies, commanded by Captain Stephen, (to whom Washington there gave a Major's commission), Stobo, Van Braam, Hogg, Lewis, George Mercer and Polson; and by Major Muse who joined Washington with reenforcements of men and with nine swivels, powder and ball, on the ninth of June. He had been Washington's military instructor, three years before, and now acted as quartermaster. Captain Mackay, with the Independent Royal Company, from South Carolina, of about one hundred men, came up on the tenth of June, bringing with him sixty beeves, five days' allowance of flour, and some ammunition, but no cannon, as expected. Among the subordinate officers, were Ensign Peyronie, and Lieutenants Waggoner and John Mercer.

"Besides the illustrious commander, who became a hero, not for one age, but for all time, several of these officers became afterwards, earlier or later, men of note. Stephen was a captain in the Virginia regiment, at Braddock's defeat, and there wounded. He rose to be a colonel in the Virginia troops, and to be a general in the War of the Revolution. Stobo was the engineer of Fort Necessity, and he with Van Braam, were at the surrender, given up as hostages to the French, until the return of the French officers taken in the fight with Jumonville; but the Governor of Virginia refusing to return them, the hostages, were sent to Canada. Stobo, after many hair-breadth escapes finally returned to Virginia in 1759, whence he went to England. Van Braam was a Dutchman, who knew a little French, and having served Washington as French interpreter the year previous, was called upon to interpret the articles of capitulation, at the surrender of Fort Necessity, and has been generally, but unjustly, blamed with having wilfully entrapped Washington to admit that the killing of Jumonville was an assassination. He had been Washington's instructor in sword exercise. He returned to Virginia in 1760, having been released after the conquest of Canada by the English; but the capitulation blunder sunk him. Captain Lewis was the General Andrew Lewis, of Botetourt, in the great battle with the Indians at Point Pleasant, in Dunmore's War of 1774, and was a distinguished general officer in the Revolution, whom Washington is said to have recommended for Commander-in-Chief. He was a Captain in Braddock's campaign, but had no command in the fatal action; and was with Major Grant at his defeat, at Grant's Hill, (Pittsburg), in September,1758. Polson was a Captain at Braddock's defeat, and was killed. Of Captain Hogg we know but little. Captain Mackay was a royal officer, and behaved in this campaign with discretion, yet with some hateur. He afterwards aided Colonel Innes, of North Carolina, in building Fort Cumberland, (Wills creek). Peyronie was a French Chevalier, settled in Virginia; was badly wounded at Fort Necessity; was a Virginia Captain in Braddock's campaign, and killed. Waggoner was wounded in the Jumonville skirmish, became a Captain in Braddock's campaign, and behaved in the fatal action with signal good sense and gallantry. Besides these there were Christopher Gist, already named, and D. Thomas Craik, the friend and family physician of Washington, until his death.

Of the Indians whose names are familiar from their connection with our history, there were Tanacharison, the Half-King of the Seneca tribe of the Iroquois, a fast friend of Washington and the English; Monacatootha, alias Scarayoody, also a Six Nation chief; Queen Alliquippa and her son, and Shingass, a Delaware chief." [The Monongahela of Old. By James Veech.]

The Captain Mackay above mentioned was Æneas Mackay who after the services referred to became in 1773, one of His Majesty's justices for Westmoreland County, Penna. At the breaking out of the Revolutionary War he was appointed Colonel of the Eighth Penn'a Regiment in the Continental Line, but died early in the war in New Jersey.

"It was a subject of mortification to Colonel Washington that Governor Dinwiddie refused to ratify the capitulation, in regard to the French prisoners. The Governor thus explained his conduct in a letter to the board of trade: 'The French, after the capitulation entered into with Colonel Washington, took eight of our people and exposed them to sale, and, missing thereof, sent them prisoners to Canada. On hearing of this, I detained the seventeen prisoners, the officer, and two cadets, as I am of opinion, as they were in my custody, Washington could not engage for their being returned. I have ordered a flag of truce to be sent to the French, offering the return of their officer and two cadets for the two hostages they have of ours.' This course of proceeding was not suitable to the principles of honor and sense of equity entertained by Colonel Washington, but he had no further control of the affair.

"The hostages were not returned, as was requested by the Governor's flag of truce, and the French prisoners were detained in Virginia, and supported and clothed at the public charge, having a weekly allowance for that purpose. The private men were kept in confinement, but Drouillon and the two cadets were allowed to go at large, first in Williamsburg, then in Winchester, and last at Alexandria, where they resided when General Braddock arrived. It was then deemed improper for them to go at large, observing the motions of the general's army, and the governor applied to Commodore Keppel to take them on board his ships; but he declined, on the ground that he had no instructions about prisoners. By the advice of General Braddock, the privates were put on board the transports and sent to England. Mr. Drouillon and the cadets were passengers in another ship at the charge of the colony. La Force having been only a volunteer in the skirmish, and not in a military capacity, and having previously committed acts of depredation on the frontiers, was kept in prison in Williamsburg. Being a person of ready resources and an enterprising spirit, he broke from prison and made his way several miles into the country, when his foreign language betrayed him, and he was taken up and remanded to close confinement.

"Van Braam and Stobo were conveyed to Quebec, and retained there as prisoners till they were sent to England by the Governor of Canada."

The following is from Evert's History of Fayette county and refers to the locality as it was about 1881 :

"Mr. Facenbaker, the present occupant, came to the property in 1856, and cut a ditch, straightening the windings of the run, and consequently destroying the outline. The ditch is outside the base-line, through the out-thrown two perches. A lane runs through the southeast angle. The ruins of the fort or embanked stockade, which it really was, is three hundred yards south of Facenbaker's residence, or the Mount Washington stand, in a meadow, on waters of Great Meadow Run, a tributary of the Youghiogheny. On the north, two hundred yards distant from the works, was wooded upland; on the northwest a regular slope to high ground about four hundred yards away, now cleared, then woods; on the south about two hundred and fifty yards to the top of a hill, now cleared, then woods, divided by a small spring run breaking from a hill on the southeast, eighty yards away, then heavily, and still partially, wooded. A cherry tree stands on one line and two crab-apples on the other. The base is scarcely visible, with all trace gone of line across the run. Mr. Geoffrey Facenbaker says he cleared up a locust thicket there and left a few trees standing, and that it was the richest spot on the farm. About four hundred yards below, in a thicket close to his lower barn, several ridges of stone were thrown up, and here he thinks the Indians buried their dead. He found in the lane in ditching, logs five feet under ground in good preservation."

"The site of the fort has not been desecrated by the plow since it came into the possession of the Facenbaker family. Mr. Lewis Facenbaker is the present owner."

The location is in Wharton township, Fayette county.

______