1855 Yellow Fever Epidemic in Norfolk & Portsmouth, VA

Additional Files:Letters

Miscellaneous Records

Archives: Hospital Documents Transcribed Edition)

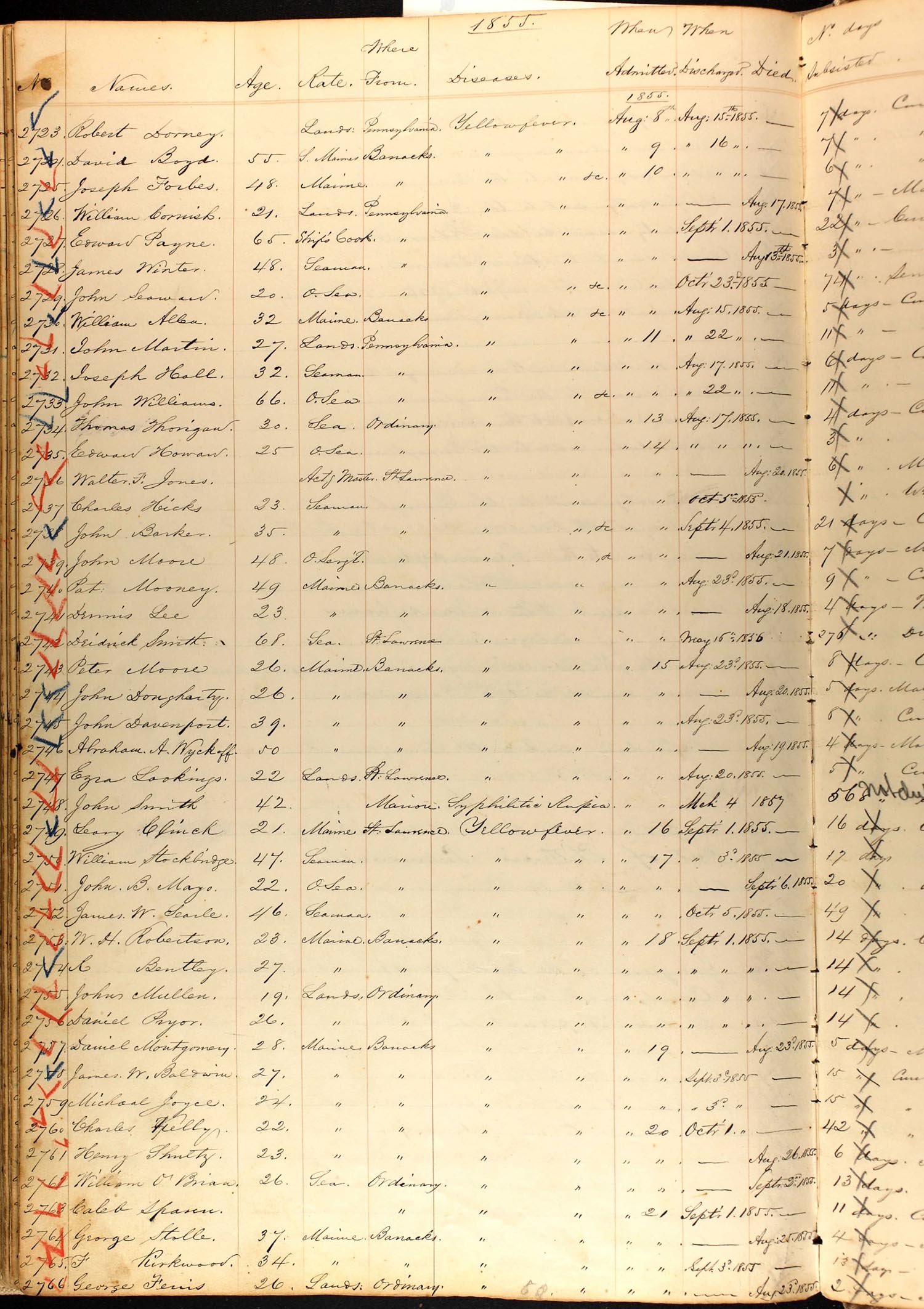

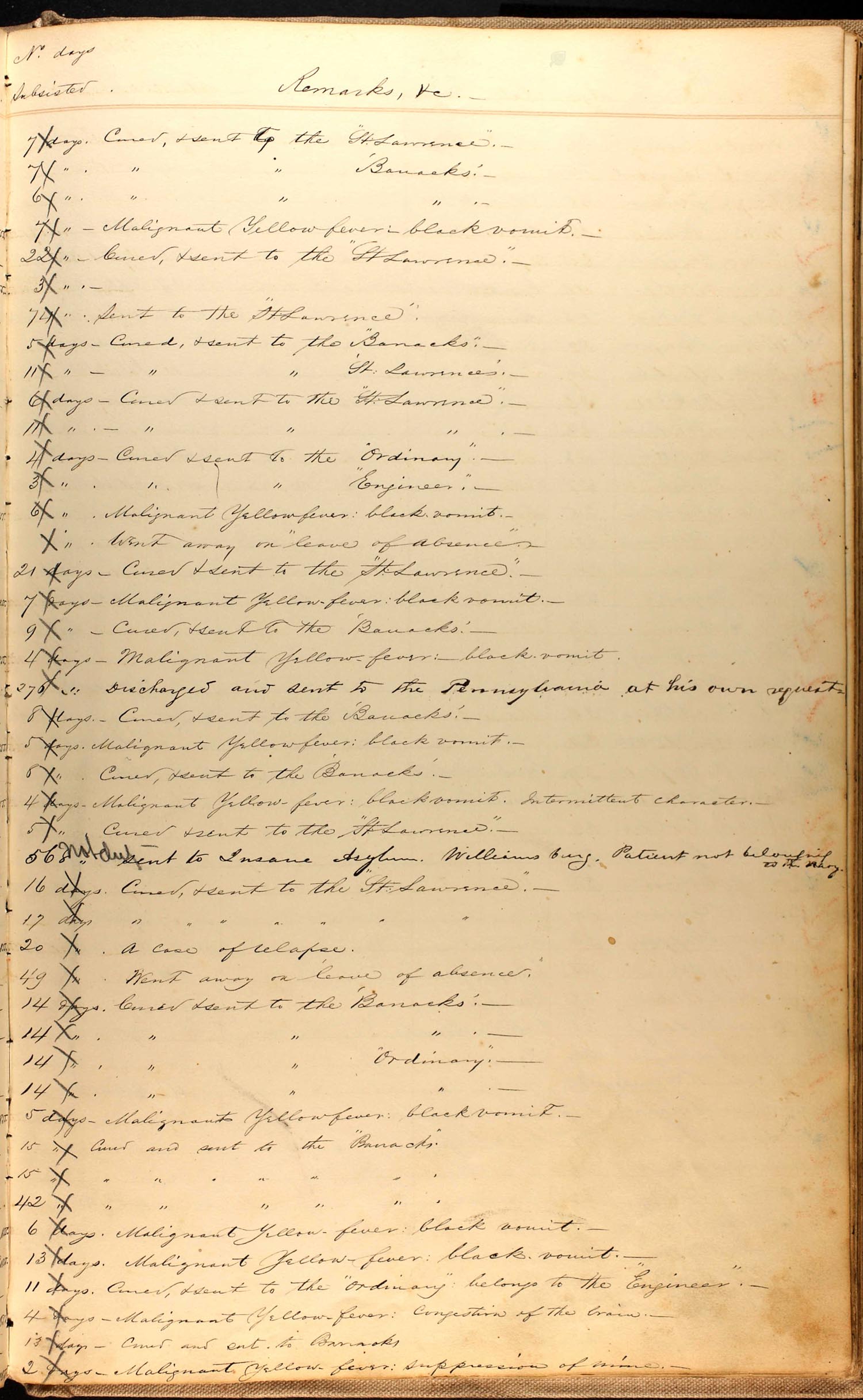

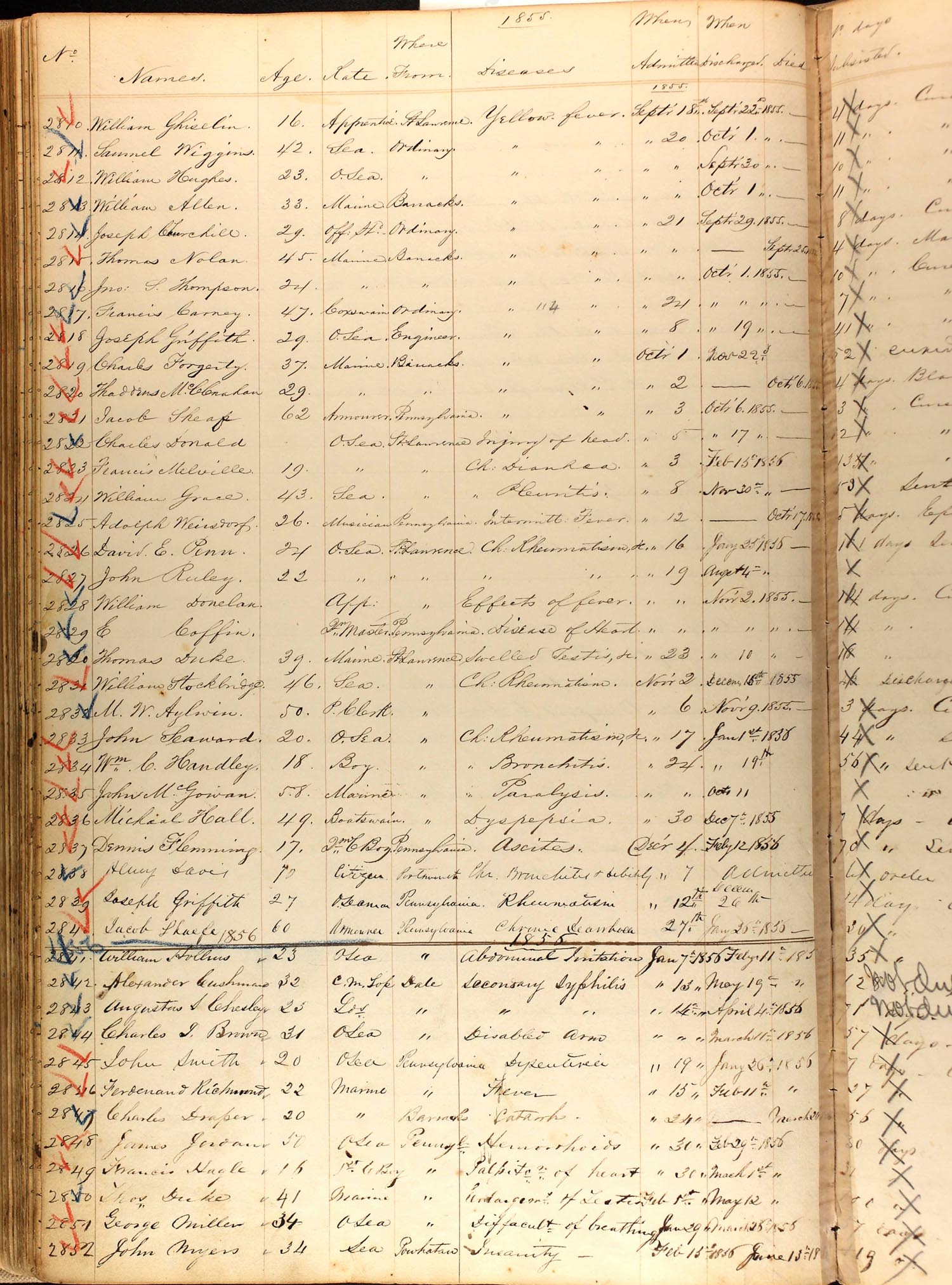

Gosport Naval Hospital Ledger

Yellow Fever Cases #2723 - 2766

Summer & Fall 1855

(enlarge further in browser)

Walter F. Jones, USN

Portsmouth Naval Hospital Cemetery

Section 2, Row 3, Plot 2

A mother's holy prayer

A mother's hand and gentle tear

have led the wanderer there.

In memory of

Walter F. Jones, U.S.N.

Born Dec 21, 1827

Died Aug. 20, 1855

This lamented & beloved young officer

died of Yellow Fever during the terrible Epidemic.

He fell in the path of duty, whilst attached as "Acting Master"

to the U. S. Ships "Pennsylvania" & "St. Lawrence."

It is a source of infinite consolation to his sisters,

to know that he died the death of a christian.

"Thy brother shall rise again."

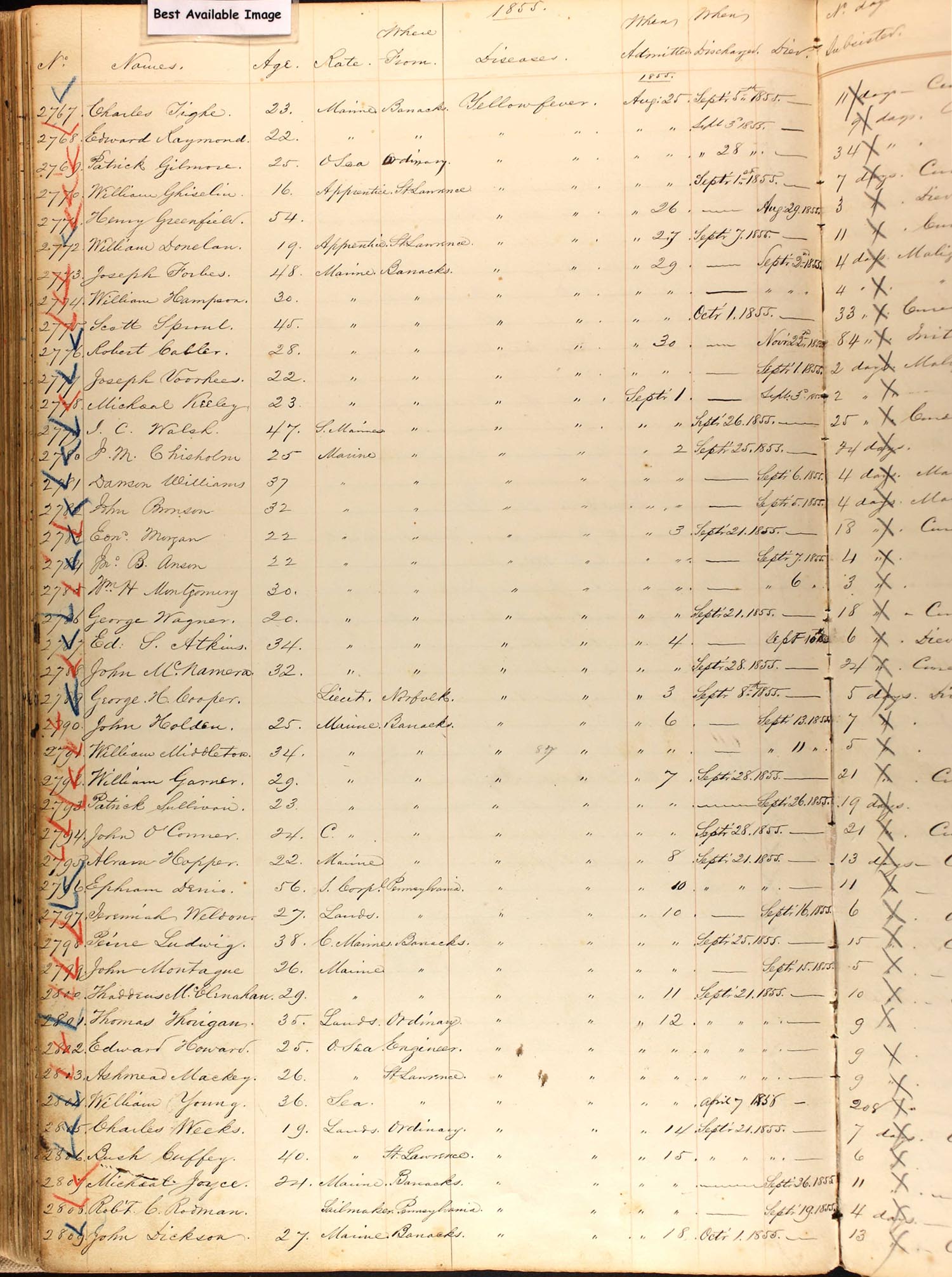

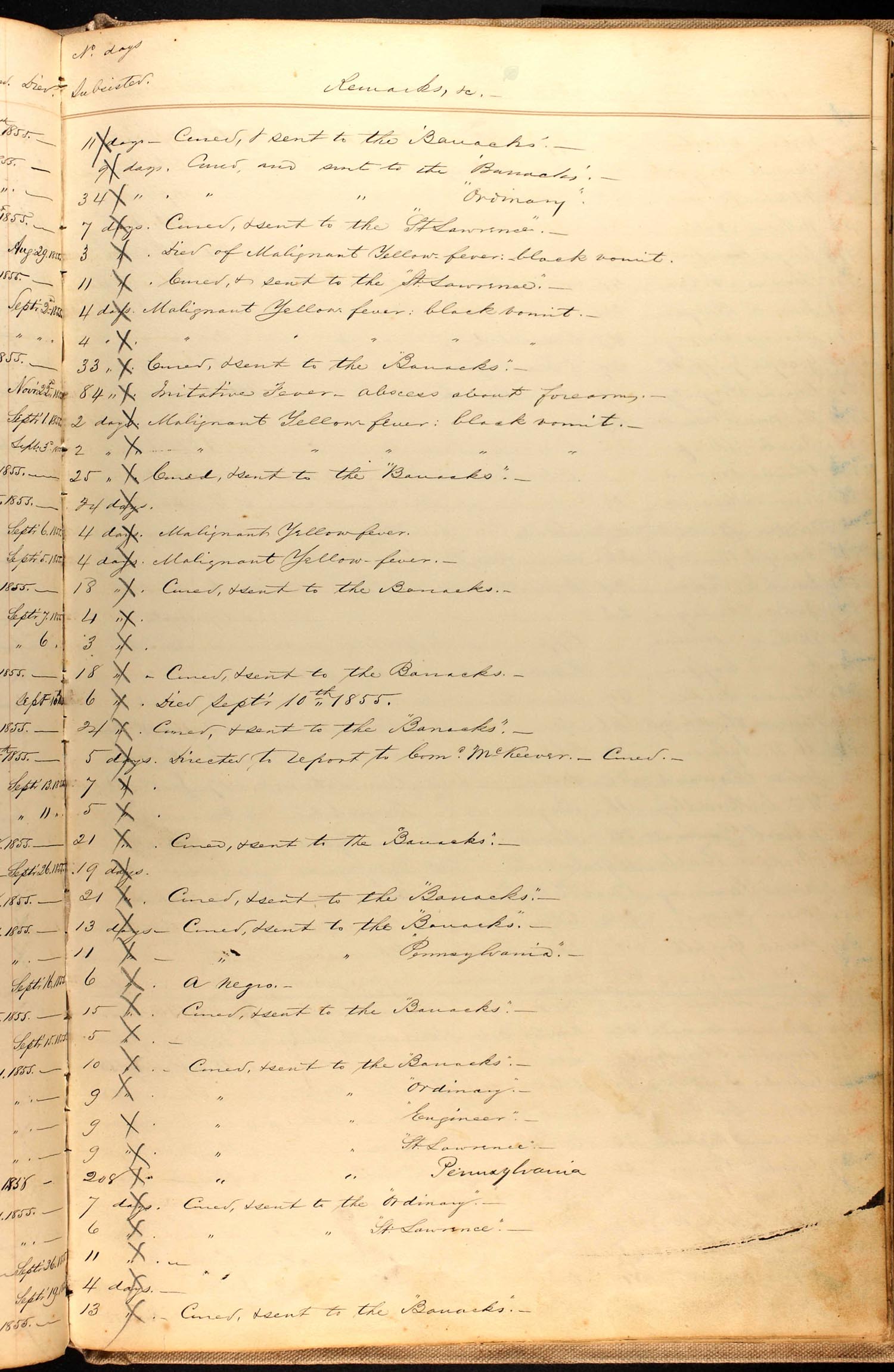

Gosport Naval Hospital Ledger

Yellow Fever Cases #2767 - 2809

Summer & Fall 1855

(enlarge further in browser)

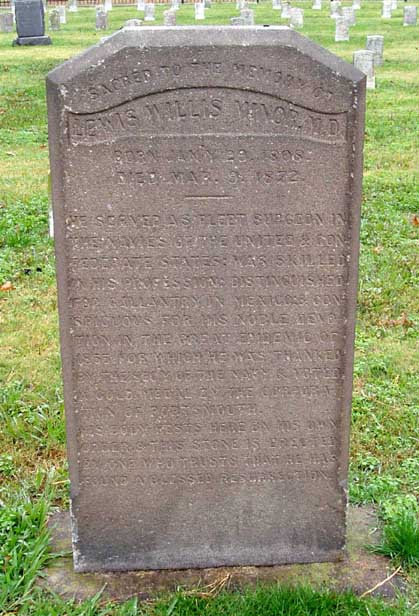

Sacred to the memory of

Lewis Willis Minor

Born Jan'y 29, 1808

Died Mar. 9, 1872

He served as fleet surgeon in the names of the United and

Confederate States, was skilled in his profession, distinguished for

gallantry in Mexico and conspicuous for his noble devotion in the great

epidemic of 1855 for which he was thanked by the Sec'y of the Navy

and voted a gold medal by the Corporation of Portsmouth.

His body rests here by his own order and this stone is erected

by one who trusts that he has found a blessed resurrection.

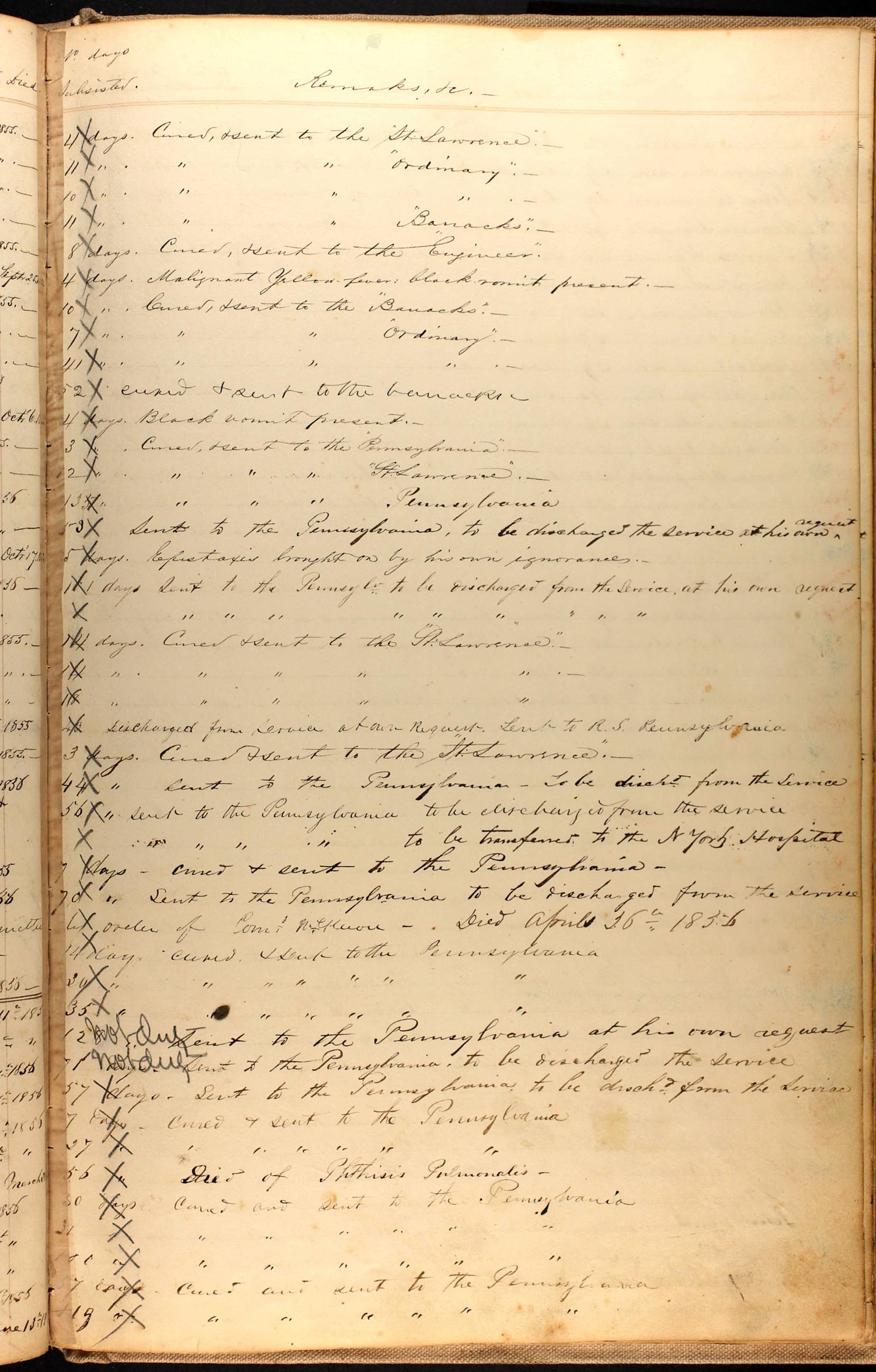

Gosport Naval Hospital Ledger

Yellow Fever Cases #2810 - 2821 (end)

Summer & Fall 1855

(enlarge further in browser)

Rev. Vernon Eskridge

Lot 277, Avenue 4, Old O, Cedar Grove Cemetery, Portsmouth

CHAPLIN VERNON ESKRIDGE

Methodist Episcopal, Chaplain Navy Yard, Gosport

Eskridge served as Navy Chaplain aboard the frigate U. S. S. Cumberland during its Mediterranean service cruise in 1852-1855.

Upon his return to the United States, he chose to come back to Portsmouth when he learned of the outbreak of yellow fever.

Worn from serving a grueling routine of comforting families, he too died as a result of the fever on September 11, 1855.

* * * * * *

George Marshall

Lot 281, Avenue 4, Old 201, Cedar Grove Cemetery, Portsmouth

Sacred to the memory of GEORGE MARSHALL

46 years a Gunner in the Navy of the United States of America

who departed this life in the 74th year of his age on the 2nd day of August 1855.

He was kind and generous, willing and ready to embark in whatever he

believed to be for the public good. He gloried in the service he had espoused, and labored

nobly to make known the principles and commend its design to others.

He was practically useful in his day and generation.

Biographical Information: John Marshall was born in Rhodes, Greece, while the Greek population was under Turkish occupation. His full name was originally Greek, of which we are not sure exactly of, but his first name was most likely Ionnis,= John. He wrote one of the first books on naval gunnery, Marshall's Practical Gunnery, published 1822. He signed on with the US Navy to better himself and escape oppression. The 1826 muster list of USS North Carolina shows George Marshall as "gunner." The 1846 Gosport Navy Yard employee list also shows Marshall as "master gunner" with pay $ 1,000 per annum.

George Marshall, age 73

Practical Gunnery, title page

Hospital Ledger No. 7 & No. 8

* * * * * * * * * *

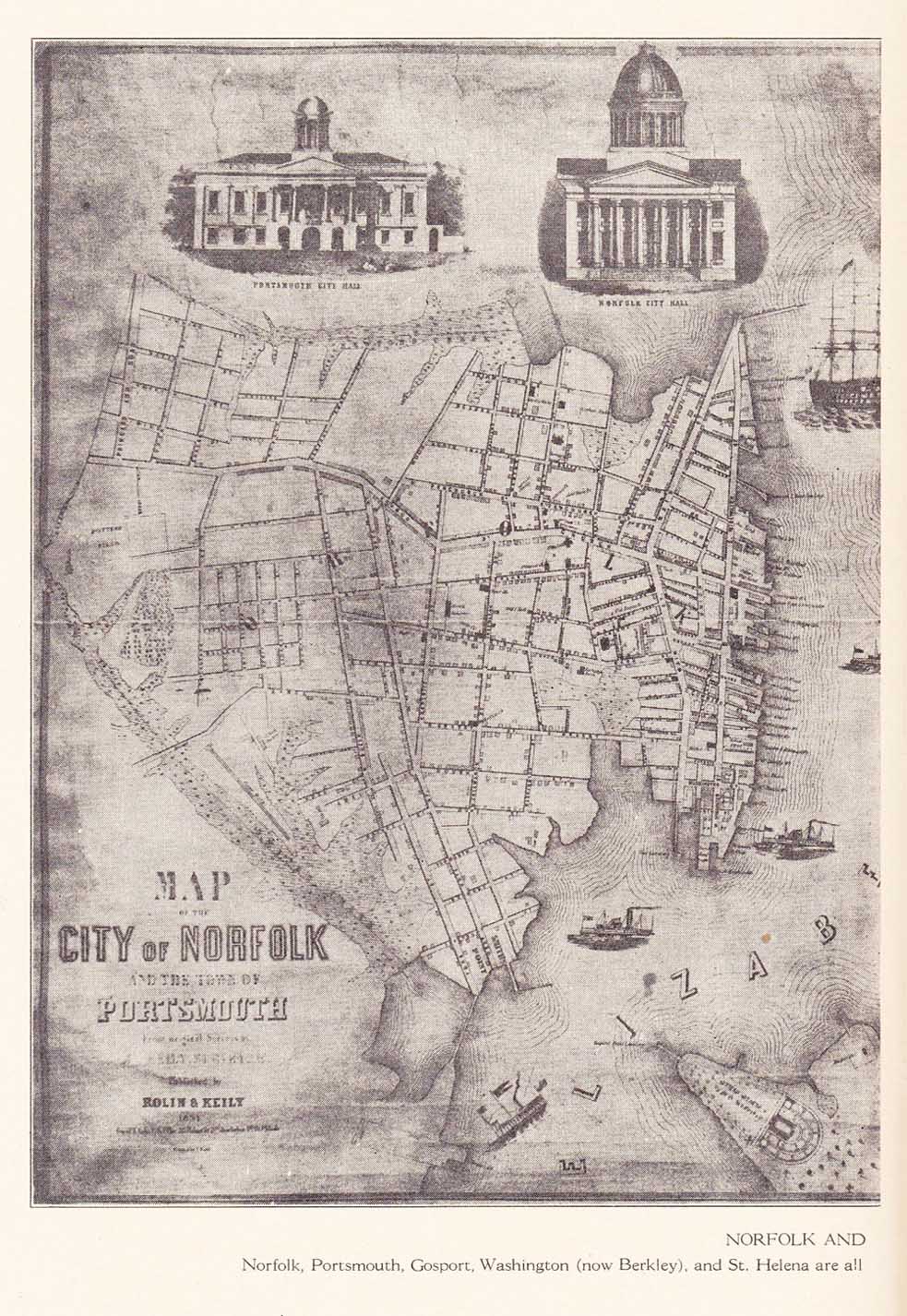

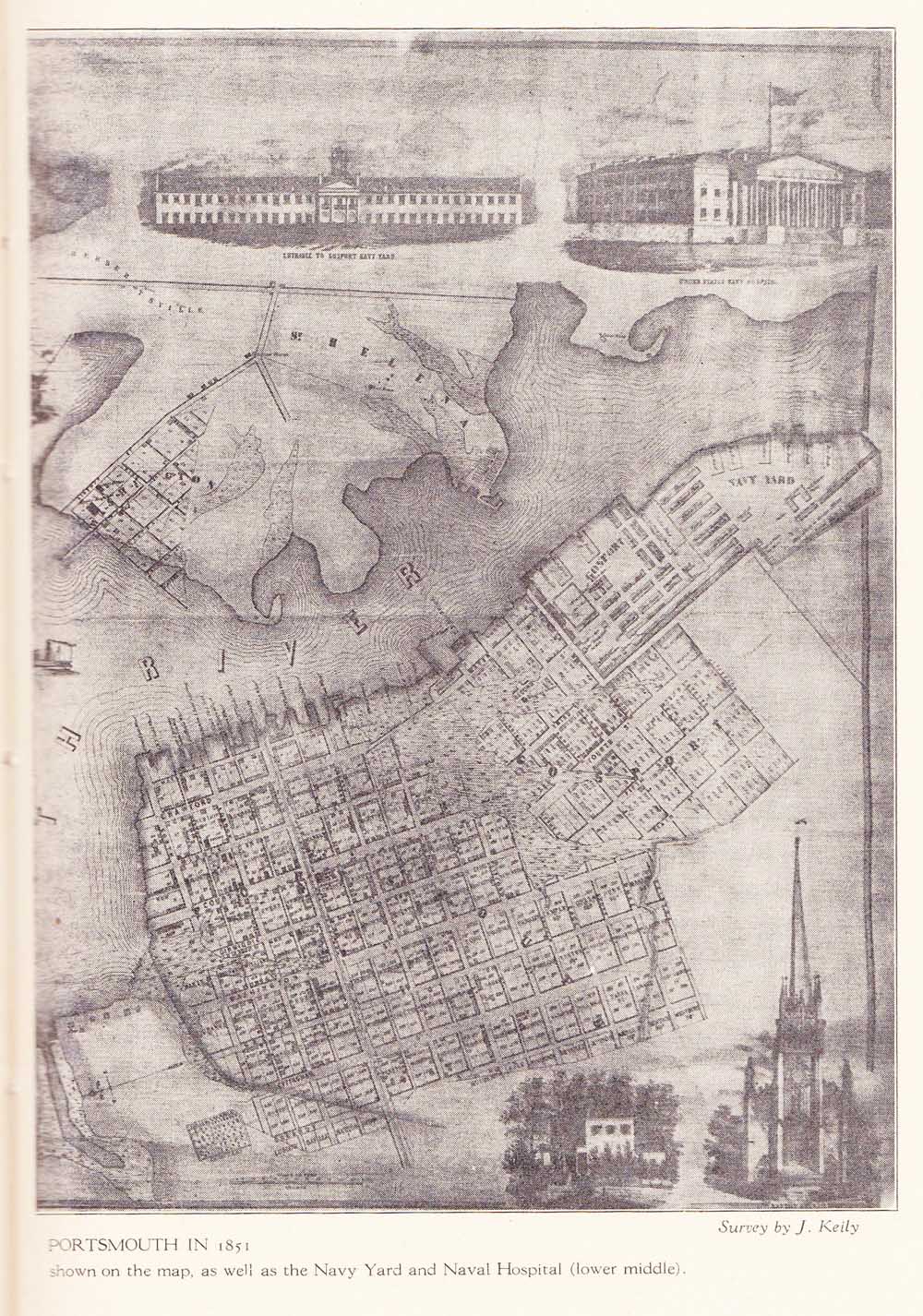

A Century with Norfolk Naval Hospital: 1830-1930

by Richard C. Holcomb

Printcraft Pub. Co, Portsmouth, Va., 1930

Chapter IX

The Yellow Fever Epidemic

In the year of our Lord 1855 a frightful crime took place at Portsmouth, Virginia. It is termed a crime because it was the evil work of the "favorite murderer" who dealt out death to man for generations. The town was living a contented life early that year, with a population of about five thousand people, yet within a period of three months about one thousand of these inhabitants were to be ruthlessly destroyed, and about the same number were to be seriously injured, though their live were to be spared.

The murders of "Jack the Ripper" in the White Chapel district of London were no more mysterious than were these murders. Not only was the frightful carnival of death carried on in Portsmouth, but in Norfolk as well. It was in Portsmouth that the mysterious riot of death was begun.

For many years the guilty one who was the dispenser of death, was unknown. He did not have a good character and for about forty-five years after these murders continued to carry on his terrible career, sometimes appearing in one place, sometimes in another, until one day a group of investigators, with the highly developed sense of the detective, working under the direction of a native Virginian, brought the guilt home to his door and exposed his wicked propensities. The story of the crime in Portsmouth may be told briefly.

The latter part of June, 1855, a steamer arrived from St. Thomas, in the Danish West Indies, where yellow fever prevailed. She bore the name of an American whose life of benevolence was entirely at variance with the misfortune of which she was to be suspected, for Ben Franklin was her name.

On the voyage up, there had been two deaths on board and when she reached Old Point Comfort, Virginia, all of her passengers, consumed by panic, left her. There was a mystery about her which foreboded great evil.

The health officer at Norfolk conceived it as his duty to place her in quarantine when she reached port. Thus she was placed under arrest like a suspicious and undesirable person. But health officers are weakly supported when they are not in position to produce the indisputable evidence of great and certain danger, which situation pertained then, but does not pertain now.

However, while the Ben Franklin was undergoing quarantine she was not above suspicion; for one of her crew sickened and died on board and his body was taken ashore and clandestinely buried in the woods opposite to her anchorage. And now the greater part of her crew deserted her, and this, with the fact that she was in need of some repairs, produced a problem.

The captain made light of the character of the deaths that had occurred on board during the passage and after arrival and assured the health officer that there had been no case of yellow fever on board. No, indeed, a suspicious health officer might be too harsh upon an innocent ship entering harbor in trouble and asking only a tiny bit of assistance which it would be so easy to give.

Health officers always have lots of trouble, but somehow most of their troubles never seem to happen. And as to the men who died on the passage, why that is very easily explained--one of the men "had expired suddenly of heart failure." Anyone is apt to do that for who ever heard of any person dying whose heart did not fail? That is a common occurrence, as common as death itself and ought to immediately remove any suspicion that the man died of yellow fever.

As for the other man who died, well it all looked like a very stupid, put up job that had been practiced on a trusting skipper. It had the appearance of being wilful on the man's part. They need more help in the fireroom and this man,

"Consenting to take the place of the fireman, to the arduous and exhausting labors of which vocation he was entirely unaccustomed, was overcome by heat, and in that condition he died." (The italics are the author's.)

He died at his labor, of a disease from the character of the symptoms one might call "work!" And everyone, even suspicious health officers, ought to realize that none of these symptoms of which he died are the symptoms of yellow fever. Try to figure it out for yourself. It is all very plain. He tried to be a fireman, which he was not, "and in that condition he died."

And now there was one other man and he was the man who died and "was buried in the woods off the anchorage." He showed less symptoms than either of the other two, for he just died. A writer of the day says:"

"From the secrecy maintained in regard to the matter, it is fair to presume that he died of some infectious disease."

The ship was in quarantine, and so the outstanding condition surrounding his death was "secrecy." And a very dangerous symptom is this secrecy.

The Ben Franklin was lying in quarantine in sight of the house of a Mr. Fox, residing at Scott's Creek, and she remained here until June 21, 1855, when with the consent of the Norfolk Board of Health, the health officer granted permission for the steamer to proceed to Page and Allen's ship yard near the Navy Yard, then more commonly called Gosport.

"This permission was given upon the express condition that her hold should not be broken out, and that only outside repairs should be done to her."

Days passed - nothing seemed to happen. Her bilge water was pumped out of her (here the little wiggle tails of the mosquito can develop into mature insects).

"A part of her stores was brought on deck, and a portion of her ballast discharged upon the wharf. A large number of men was working about the vicinity where this occurred. Now it was that her repairs commenced. Hands were sent down into the hold to work on her engines and boilers, and continued thus employed as long as she remained at the yard. Carpenters were busy about her decks and in repairing her masts and spars. No apprehensions at her presence were entertained until Sunday, July 8th, a day that will long be remembered by every citizen of Portsmouth."

And now something happened and we will use the words of a physician, who himself had the disease and was treated for it at the Naval Hospital, and was one of the 587 patients who were treated in that institution. He recovered, however, and lived to tell the story of the mysteriously guilty one's work. And from the book of Doctor J. N. Schoolfield quotations are freely made:

"A young man-Carter-a machinist by trade, coming from the city of Richmond, in search of employment, was engaged to assist in repairing the machinery. He went to work on the 3rd of July, and was thus employed all that day. The 4th being a holiday, he kept it as such and spent the day at Old Point, where he indulged freely."

He must have had the time of his life. He had gone to the fort to hear the guns roar, and to celebrate the day in true pre-prohibition fashion!

"On the next day he was taken sick having the ordinary symptoms of fever. Nothing calculated to attract the attention of his physician to his case as being at all extraordinary until the morning of the 8th when it assumed an alarming aspect. Then it was that unmistakable symptoms of yellow fever were developed. The attendance of several medical gentlemen in consultation was requested, and among them were Dr. Thomas Williamson, and Dr. Green, both belonging to the Navy. These men had seen much of that disease during their connection with the naval service. The case was thoroughly examined and a minute inspection of the matter ejected from the stomach was had. There was no difference of opinion among them. It was pronounced to be genuine yellow fever, and the matter true black vomit. The poor fellow survived but a few hours, and died in the afternoon of the same day."

The narrator stresses the fact that the man was a "newcomer," a stranger to the community and had been there but a few days. In fact there seems to be a grudge against him because he was a newcomer, and it soon will be seen what unjust suspicion was the fate of these newcomers. But to continue from Dr. Schoolfield's narrative:

The fact becoming public that a man had died of yellow fever, accompanied by black vomit, spread rapidly through out the community, and created the most intense excitement. The matter formed the subject of discussion among groups at the corners of the streets, and instantly fear and consternation seized hold on the public mind. Imagination could little divine what terrible results would ensue from this small beginning. Sunday though it was, the town council were convened in extraordinary session and the case officially reported to them. The concurrent testimony of the physicians who had seen the patient was of such a character as to leave no doubt as to the nature of the disease which had terminated Carter's life. A resolution directing the town Sergeant to cause the immediate removal of the Ben Franklin to the quarantine ground, was offered and unanimously adopted; for all came to the conclusion at once that she was the source of the disease. (The italics are the author's)

The Ben Franklin is now again under suspicion, and we will see how the suspicion again fades away and the strong statement is made that yellow fever would have been epidemic at Norfolk and Portsmouth, even if the steamer Ben Franklin had never visited their shores.

And on that same Sunday the Ben Franklin went back to quarantine, though not without strenuous protests by her Captain, who, after obtaining legal advice, finally acquiesced in the action of the authorities. And there is every reason to believe that Captain Harrison felt that his ship had been the object of unreasonable suspicion, and it will be shown how anxious he was to have his vessel visited and thoroughly examined, that the innocence of the ship might be fully established.

Again and again will be observed from Schoolfield's narrative the accumulation of evidence against the "newcomer" in the early cases. There were certain facts about the trail of the Ben Franklin which clearly showed she was not above suspicion both before and after she arrived at Page and Allen's ship yard.

A few days after she left her quarantine anchorage for the ship yard, namely on June 24th, a Mrs. Fox living at the bifurcation at Scott's Creek, in sight of the ship's anchorage, came down sick and died five days later. This was before the death of Carter. She was a native of New Jersey, 65 years of age, had only been in Norfolk County six weeks, and had never been into the town of Portsmouth after her arrival at the house. She, too, was a "newcomer," like Carter.

After the ship had gone back to quarantine a lighter loaded with wood came along, on the way to Norfolk market. It was in charge of two innocent "newcomers, " Elvy Trotter, a negro, and Noah Wickins, a mulatto. The lighter, hailed by the steamer, was induced to come alongside.

The wood was purchased for the use of the ship and the two men remained to deliver it, intending to get away the same day, but a storm arose and they were compelled to remain aboard all night. They slept on the deck of the steamer and next day started for home, eight miles distant, and arrived there the following day. They were both taken ill the day of their arrival home and both died on the seventh day of their illness. Neither of the men had been to Norfolk or Portsmouth. They, too, were "newcomers."

About four days after the ship had returned to quarantine her Captain appealed to have a thorough examination made of her, which was made July 12th, and Dr. Schoolfield tells the results of examination:

"So far as it was possible to judge by such examination, she appeared to be in a healthy condition. She certainly was clean, and there were no disagreeable odors, either about her decks or in her holds or engine rooms. There was very little water standing in the bilge, and such as was there, we ascertained to be clean and sweet, whether made so for the occasion of our visit, we will not pretend to say; but she certainly was in as good condition as sea going vessels usually are, and we gave him a paper to that effect, in order to aid him in obtaining a clearance from the port, as he expected to be able to sail the next day. The captain informed us that the repairs were still going on, and that mechanics had been at work in her engine rooms every day since return of the steamer to quarantine, and that among them there was no sickness of any kind, of which he was aware."

On Friday, the 13th of July, the Ben Franklin was ready to depart, and with her going the disease broke forth with a vengeance. Deaths began to appear with alarming rapidity, several each day. Business came to a standstill, people began to flee, and those who remained, including the physicians, were stricken down.

On Wednesday, July 25th, it appeared in Norfolk. A clerk employed at Page and Allen's ship yard, residing in Norfolk, sickened that date and died the Saturday night following. By the second of August there had been seven deaths from the fever in Norfolk. On August 7th, another case appeared and now that city became greatly concerned. A relief committee had been formed in Portsmouth, and an association later to become known as the Howard Association, was formed in Norfolk.

On July 28th the Common Council of Portsmouth, looking to the Naval Hospital for relief, appointed a committee composed of Colonel W. Watts, Dr. G. W. Peete and Mr. C. W. Murdaugh, who proceeded to Washington, called upon the Secretary of the Navy and requested his assistance. Dr. Whelan, the then Chief of the Bureau of Medicine and Surgery, at once gave consent for use of the Naval Hospital, and during the following three months nearly six hundred cases of the fever were admitted for treatment. The mortality rate among these cases was more than thirty-five per cent.

The earliest cases of yellow fever to enter the Hospital came from the Marine Barracks which suffered severely from the disease, nearly one-half of the personnel falling victims to the epidemic. The first case which originated at the Hospital developed about the end of August in the son of the commanding officer, a young boy ten years of age who had only recently arrived from Fredericksburg, Virginia. There was also a young lady in the family of one of the medical officers who died of the same disease.

The disease disappeared as quickly as it came, and by the last of October the last of the citizen patients left the Hospital.

Through the month of August the disease was in full sway in Norfolk. Mr. William Forrest, who lived through the epidemic, wrote of the harrowing tumult of death:

"On the 24th of August there were at least 500 cases in Norfolk, and six apothecary establishments were driving a large business, working day and night, with all the force the proprietors could command; and on the 25th there were about forty burials.

"The Howard Association, of Norfolk, and the Relief Committee, of Portsmouth, had been fully organized, and had commenced their career of immense usefulness. The great utility of these timely organizations, was strikingly apparent. The citizens of Norfolk were soon falling at the fearful rate of 60, 70 and even 80 per day, and of from 20 to 30 in Portsmouth. It was then that some were appalled and chilled with fright, while other were apparently callous, careless, and reckless, and went about the work of boxing up and removing the dead, with but little appearance of fear or agitation."

On the 29th of August, the Portsmouth Transcript contained the following statement:

"We do not know what would have been the extent of the mortality and misery, had not the Council succeeded in obtaining the use of the United States Naval Hospital in the present emergency. To the President of the United States, as well as to the able and humane report of Surgeon Whelan, Chief of the Medical Bureau, we are mainly indebted. The Commodore of the Yard here, too, has afforded every facility in supplying the demand for coffins, which Mr. Stoakes could not wholly meet."

Another observer who wrote during the midst of this month, a Rev. Dr. Doggett, told in vivid words, the extremely desperate situation that confronted on all sides.

"The highest medical ability has been baffled at every turn, exhausted in every effort, and has been compelled to acknowledge itself as weak as the baldest empiricism. Prosperous congregations have been despoiled of their membership, and pastors have been severed from their flocks. Happy households have been agonized with the spectacle of their loved ones dead and dying, at the same moment. Survivors have been doomed to the melancholy task of nursing, closing the eyes, shrouding and burying their own relatives. Insufficient help has left others to suffer in solitude, and to expire unattended. Orphans have clamored to parental hearts motionless in death, and have increased in numbers that will tax, for years, the charities of the good. Markets have been deserted; food has become scarce; friends powerless; and coffins have been in such demand, that undertakers, at home, have been unequal to the supply; bodies have putrefied in the open air, been put into rough and unsightly boxes, or buried, by heaps, in pits; and the impurity of the infected air has emitted a corpse-like stench. Entire families have been dismembered or extinguished. No one has been left to call or answer to the hereditary roll, and houses, once filled with cheerfulness and mirth, are as tenantless as the desert, and as voiceless as the tomb. Thoroughfares, once gay with business or with fashion, are horribly vacant. The hum of human concourse has yielded to the rattle of the physician's carriage, or the hollow rumble of the sluggish death-cart. The ominous plague-fly has made its disgusting appearance, and the howl of the watch-dog separated from his master, has added its doleful note to the solemnities of a decimated population. Multitudes, seized with apprehension, have fled from their homes in affright, are now scattered over the adjacent country, awaiting, with mingled solicitude and hope, the consummation of this startling havoc of their friends and fellow-citizens. Still the tragedy goes on, and who is able to calculate its catastrophe or its termination! During this period, in our judgment, few, if any, less than three thousand human beings have left the walks of the living, to inherit the abodes of the dead, and with magic, but revolting rapidity and numbers, have created a populous city of graves conterminous with that so recently occupied and animated with their presence."

Tired, worn, weak, with backs-to-the-wall, and dazed, the twin cities faced the month of September. It seemed as if the knife of vengeance had slashed deeply. In this anemic condition even a few less cases seemed encouraging. A special correspondent at Norfolk, writing to the Richmond Dispatch, told of the rays of hope that filtered through during those pitiless mid-September days:

"Norfolk, Sept. 11, 1855--There appears to be some abatement of the violence of the scourge; but it still rages fearfully. The work of death goes on, and there are many new cases. With a large population the number of deaths would be correspondingly large. Norfolk, but two months ago, so busy, bustling, healthful and prosperous, now bears, on every deserted street, avenue, and square, sad evidences of the desolating reign of the pestilence. Widows and orphans have been made by the hundred. A thousand homes, but recently happy, are now desolate, sad, and comfortless; and in some cases, the unsparing arm of the angel of death has claimed all, and they are quiet and stirless tenants of the grave-yard. How terrible and extraordinary has been this visitation of Providence! But I give you some particulars: The numbers of burials on the 1st inst. was about 76; on the 2nd, 45; 3rd, 52; 4th, 58; 6th, 66; 7th, 48; 8th, 52; 9th, 56; 10th, 65. This is an awful mortality for so small a remaining population.

"Wednesday, 12th.--Many of our citizens are still falling victims to the scourge. There are lamentation and mourning in many parts of town and in Portsmouth. We are yet in the midst of one of the most terrific calamities that ever visited any place. The people are still falling beneath the leveling arm of the destroying angel, at the rate of fifty a day or more! Men, unaccustomed to weeping, are shedding tears now, and hearts are made to feel deeply and almost to break with grief. All nature looks beautiful and charming; but here, in our ill-fated city, the silence of death and the look of desolation chill the heart, and depress the spirits.

"We hear scarce a sound but that of the hammers, and saws, and wagons of the undertaker, and the rattle of the physicians' vehicles. Business has ceased, and the voice of mirth and revelry is not heard."

Help came in from all sides, for money was subscribed generously, the Howard Association receiving nearly $180,000. Doctors, Sisters of Charity, brave-hearted men and women sprang to answer the call of distress.

One hundred and seven doctors came from distant cities and states, of whom twenty-four died in the discharge of their duties. The newspapers had suspended. Early in October things began to mend a little. The Daily Southern Argus went to press after thirty-nine days' suspension. Therein wrote Mr. A. F. Leonard, the editor, whose labors were turned from the sick and dying:

"We have seen our lately flourishing mart reduced to the scanty number of 4,000 surviving souls. In the short space of less than ninety days, out of an average population of about 6,000, every man, woman, and child (almost without exception) has been stricken with the fell fever, and about 2,000 have been cured--being not less than two out of three of the whites, and one out of three of the whole abiding community of Norfolk, white and black. One-half of our physicians who continued here are in the grave, and not less than thirty-six physicians, resident and visitant, have fallen in Norfolk and Portsmouth."

The Naval Hospital had labored at full capacity, for a total of 587 fever cases were admitted between the date of July 25th and November 10th, when the last was discharged, which were distributed as follows:

on AdmissionWhite men White women White boys White girls Black men Black women Black boys Black girls Total admissions 587

Total discharges 379

Total deaths 208By the middle of October things began to look as if the epidemic had run its course. The Secretary of the Navy, who had watched the progress of the epidemic with keen interest, wrote a letter on this date to Surgeon Lewis Willis Minor, then in charge of the Hospital:

"Navy Department. Oct. 15, 1855.

"Sir: Now that the terrible pestilence with which the cities of Portsmouth and Norfolk have been visited has greatly subsides, and is I trust wholly subdued, it is due to you and those associated professionally with you, not only to impart the praise which the Commandant of the Norfolk Naval Station deems to be due to you and them, but to express the appreciation in which the Department holds the self-sacrificing and unflinching spirit, in acts of humanity, which have been devoted to the suffering sick by the Medical Officers of the Navy attached to the Naval Hospital near Norfolk.

"The Commandant of the Station has very properly remarked that 'it is proper to bestow a tribute of praise upon the Medical Officers of that institution. They have performed their duties assiduously and faithfully during those laborious and trying times," in which sentiments the Department fully concurs.

The unremitting attention and the untiring zeal and devotion which have marked the course of yourself and assistants are worthy of all praise, and receive the gratitude and admiration of all.

"The Department tenders to you and to them its thanks for the magnanimous efforts bestowed upon the afflicted.

"Be please to make known to your assistants how highly their good conduct during the ravages of the destroyer is appreciated.

"I am, very sincerely,

"Your obedient servant,"J. C. DOBBIN

"Surgeon Lewis W. Minor

"U. S. Naval Hospital, near Norfolk, Va."To which testimonial Surgeon Minor replied promptly:

"U. S. Naval Hospital,

"Portsmouth, VA.

"October 20, 1855."Sir: I have the pleasure to acknowledge the receipt of your letter of the 15th instant, expressive of your appreciation of the services rendered by my professional associates and myself 'to the suffering sick,' during the prevalence of the pestilence which has recently so afflicted the people of our vicinity.

"I am fully sensible of and highly appreciate the honor done us, by the very flattering notice taken by the Department of the manner in which our duty has been performed by my professional associates in this Hospital and myself. The praise also bestowed by the Commander of the Station is highly gratifying.

"It is impossible, sir, to express fully the high estimation in which I hold the conduct of the gentlemen who have served with me during the continuance (as an epidemic) of the really fearful disease which has so depopulated this region.

"So admirable has been the conduct of each that I can distinguish none individually. Suffice it, then, to say, that, in my opinion, Drs. T. B. Steele, James F. Harrision, Randolph Harrison, John C. Coleman, and Frank A. Walke, are entitled to any and every commendation the Department may think proper to bestow upon officers who, in the FULLEST sense of the expression, HAVE DONE THEIR DUTY.

"In accordance with your request to that effect, I shall have great pleasure in making known to my official associates how highly the Department appreciates their good conduct during the ravages of the destroyer.

"I am, very respectfully, sir,

"Your obedient servant,

"LEWIS W. MINOR, Surgeon."Hon. J. C. Dobbin,

"Secretary, U. S. Navy."The records also show that three Sisters of Charity, Sisters Bruno, Isabella and Urbana, worked untiringly in the wards under the immediate charge of Dr. Steele.

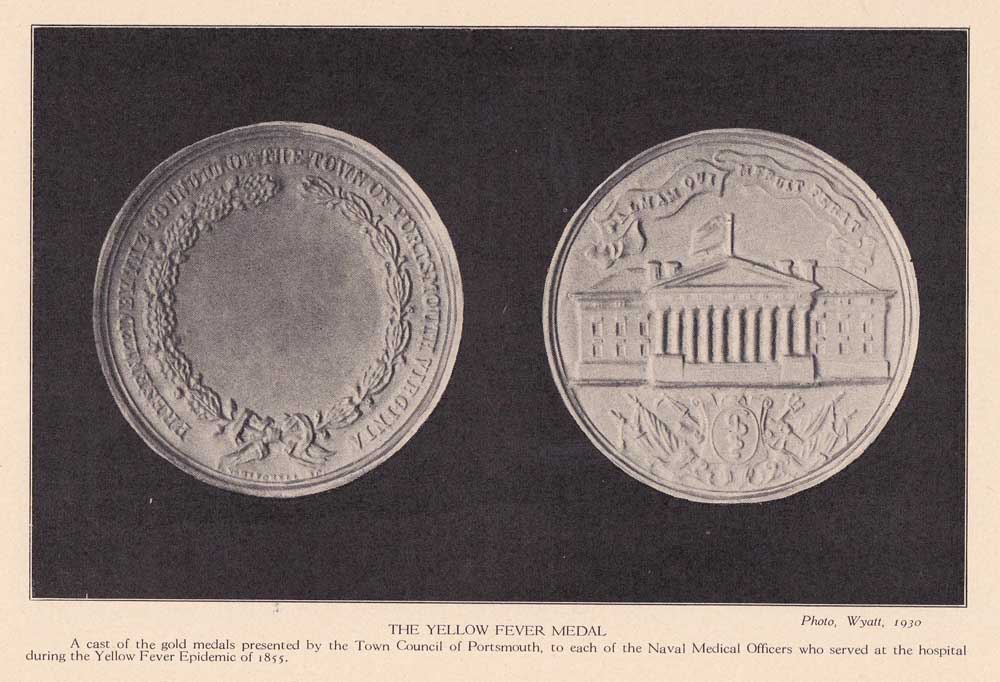

As a token of appreciation the Common Council of the town of Portsmouth, meeting in February, 1856, adopted resolutions and directed that gold medals with suitable devices and inscription be presented to the Surgeon of the Hospital and his assistants, and at a subsequent meeting $1,500 was appropriated for this purpose.

The medals as case, show a relief of the old Hospital on one side and the opposite side was inscribed: "Presented by the Council of the Town of Portsmouth, Virginia."

The resolutions read:

"Resolved: That our grateful acknowledgements are tendered to Lewis W. Minor, Surgeon of the U. S. Naval Hospital, and to his able and humane assistants, Thos. B. Steele, James F. Harrison, Randolph Harrison, John C. Coleman and F. A. Walke. These excellent men and skillful physicians were in season and out of season, at the beds of our sick and dying people, ministering to their necessities, and smoothing their pillows in the solemn and trying times when their labors were so accumulated, ennobled their positions and dignified their honorable profession.

"Resolved: That as a memorial of them and a testimonial of the public appreciation of their valued services, a committee be appointed, with instructions to have executed six gold medals with suitable inscriptions and devices and that one be presented to each of these physicians, together with a copy of this and the foregoing resolution."With the pestilence over, people turned their attention to speculations as to what had caused it. Mr. William S. Forrest, in his book "The Great Pestilence in Virginia," treated of this phase extensively and quoted the following "simple explanation" from the Westminster Review:

"It is at night that the stream of air nearest the ground must always be the most charged with the particles of animalized matter given out from the skin, and deleterious gases, such as carbonic acid gas, the product of respiration, and sulphuretted hydrogen, the product of sewers. In the day, gases and vaporous substances of all kinds rise in the air by the rarefaction of heat; at night, when the rarefaction releases them, they fall by an increase of gravity, being imperfectly mixed with the atmosphere--while the gases evolved during the night, instead of ascending, remain at nearly the same level. It is known that carbonic acid gas, at a low temperature, partakes so nearly of the nature of a fluid, that it may be poured out of one vessel into another; it rises at the temperature at which it is exhaled from the lungs, but its tendency is towards the floor, or the bed of the sleeper, in cold and unventilated rooms.

"In the epidemics of the middle ages, fires were lighted in the streets for the purification of the air; and more recently, trains of gun-powder have been fired and cannon discharged for the same object; but these agents, operating against an illimitable extent of atmospheric air, have been on too small a scale to produce any sensible effect. It is however, pronounced by the best authority quite possible to heat a room to produce a rarefaction and consequent dilution of any malignant gases it may contain; and it is, of course, the air of the room, and that alone, at night, which comes into immediate contact with the lungs of a person sleeping."

In both Portsmouth and Norfolk there was at first an inclination to connect up the disease in some way with the Ben Franklin, but afterward and little by little, the conviction grew that there was some other cause.

Was it not apparent that the disease did not break out with fury until after that Friday, July 13th, when she sailed away. Certainly until the last of July the disease seemed to be confined to Gosport, near the Page and Allen ship yard and the Navy Yard. It was early in August before the disease appeared in force in Norfolk. Dr. Schoolfield reasoned:

"The question of the non-contagiousness of yellow fever has been so fully settled by the course of the late epidemic, that we shall only advert to it very briefly in this memoir. In olden times the faculty were very much divided in the opinion in relation to it, but the evidence going to show that no one ever contracts the disease from contact with an individual laboring under it, is so overwhelming, that very few, at the present day, believe in its contagiousness. Dr. Rush, the very best authority on this disease, did at one time entertain this belief, and in his earlier writings, ably argues in its support; but a more intimate acquaintance with the disease convinced him that he was in error, and in a most lucid and able letter to Dr. Miller, dated October 8, 1802, he repudiated the views which he had labored so hard to propagate. He concludes in these words: 'The yellow fever is not derived from specific contagion; it is always generated by putrefaction; it is not contagious in its simple state, and never was; it is not, and, while the laws of nature retain their present order, never can be imported, so as to become an epidemic in any country.' This is very strong language, but no stronger than the circumstances attending the progress of the late epidemic would warrant the use of at this time. In no instance coming under our observation did a case occur, when a suspicion of its being contracted by contagion, could, for a single moment, be entertained. If the knowledge of this (the true) doctrine of yellow fever had been accepted the deep disgrace produced by the heartless brutality which characterized the proceedings of the authorities of Suffolk, Weldon, Isle of Wight County, and other places, with regard to their quarantine regulations; the cities of Norfolk and Portsmouth would have been spared much of the suffering and death which befell their unfortunate inhabitants. We should have had no threats of the imposition of heavy fines on the fugitives from those plague-stricken cities; nor would practicing physicians have refused to attend upon these same fugitives, when overtaken by the plague-fiend at their very doors, as did actually occur in at least one instance.

"Had the quarantine regulations of the above-named places been adopted generally, and rigidly enforced, as they were attempted to be by them, Norfolk and Portsmouth would have presented an aspect of horror only to be compared with the sufferings of the poor wretches who were confined in the black hole at Calcutta. We do not advert to this subject for the purpose of producing irritation and unkind feeling, but solely with the view of inculcating the fact, that the universal testimony of all well informed physicians at the present day goes to prove that YELLOW FEVER CANNOT BE PROPAGATED BY CONTAGION, and that, to take the disease, a person must be exposed to the atmosphere of the locality where the fever prevails."

Note there was no suspicion of the guilty insect anywhere in this! There is no doubt of the truth of the deductions as to the non-contagious character of the disease, for that has since been definitely proven. This argument is cited because the quarantine regulations of neighboring communities extended no welcome to refugees from that mysterious "plague-fiend."

The narrative contained four conditions which refer to that mysterious "miasma" that seemed to arise from hot swamps and give rise to malarial and yellow fevers:

"Before proceeding to the narrative of the first cases of the fever which appeared in Portsmouth and vicinity during the last summer, we shall very briefly give our views as to the exciting causes to which it owes its origin. These may be readily surmised by an attentive perusal of what has been said in the preceding pages. We think the facts presented by the history of the same disease in other localities, in past years, warrant us in drawing the following conclusions:

"1. That the condition of Page & Allen's wharf, particularly that of the dock, to which we have before called attention, filled up as it was with an immense mass of vegetable matter, acted upon by water from the river, and by rains, in conjunction with the extreme heat which prevailed at the time, and also of the shores of the creeks, and the marshes in the same vicinity, exposed as they were to the burning rays of the sun, had much to do with fomenting and bringing into action the malaria which gave birth to the pestilence.

"2. That the filthy condition of the premises known as Fish Row (Irish Row), the want of ventilation therein, and the overcrowding of its inmates, rendered them peculiarly susceptible to the influence of malaria.

"3. That the heavy rains of April and May, followed by a long continued drought, with the prevalence, for many successive days, of calms, or light southerly winds, thus causing the tides to be continuously low for an unexampled period of time, furnished another element necessary for the formation of malaria; and

"4. That the extreme degree of heat, for which June and July were so remarkable, supplied the last essential ingredient in the production of that noxious agent.

"All authorities are concurrent in the opinion, that yellow fever only prevails in very hot weather; that a high degree of heat, of itself, is not equal to its origination; but that, in combination with it, there must be vegetable matter, undergoing the putrefactive process by aid of the presence of moisture. The generation of malaria by the combined action of these three elements, heat, vegetable matter, and moisture, is retarded by too free a supply of water. Low marshy grounds, even with intense heat, will not give rise to it if they are covered with water, because the emanations from the marsh are drowned by the stratum of water lying over it; but if the muddy bottom is just moistened and exposed directly to the sun's rays, a species of fermentation is noted. This probably would not be so efficacious in the production of fever with a brisk circulation of the air, as from high winds, as it would be during the prevalence of calms, or light winds.

"The presence of these elements, so necessary to the formation of malaria, was particularly to be noticed in Gosport, where the fever took its rise, in the midst of a population ripe for the development of disease, by reason of so large a proportion of them being unacclimated and living huddled together in close, badly lighted and worse ventilated rooms. A close scrutiny into the history of this formidable disease, will establish the fact, that it never yet has made its advent in situation remote from wharves, docks, or low marshy and new made grounds. Except on ship board, and there are to ge found the same elements which exist in so great profusion in the localities just referred to. Whether or not the Ben Franklin had yellow fever on board when she arrived at Norfolk, we will not take it upon ourselves to declare; but with a full consideration of all the circumstances connected with the beginning of the epidemic, we do not hesitate to affirm it as our belief that the yellow fever would have visited Norfolk and Portsmouth even if that steamer had never reached their shores. The facts associated with the history of the first cases which came to the knowledge of the profession, well, we think, substantiate us in this position."

But the Ben Franklin had all to do with it, as the "plague-fiend" was a passenger aboard that vessel. Of course science today knows who was the guilty one, for it was a mosquito who was breeding in the bilge of the Ben Franklin. Today, in light of scientific research, the "simple explanation" of the Westminster Review will not suffice. Today it is clear that the two men who died on the voyage from St. Thomas probably died of yellow fever, that there were probably other cases on board who did not die, and there are good grounds to believe that the man who was "buried in the woods" died also of yellow fever.

And now it can be understood how the woman residing on Scott's Creek was probably bitten by an infected mosquito blown ashore. And it can be understood how Carter was infected on July 3rd, the day he worked in the hold, and also how the two wood venders contracted the disease, because they, too, died of yellow fever.

It is all quite clear now, because, after forty-five years, the mosquito has stood so truly condemned of the guilt of spreading this disease that this knowledge has lessened the fear of the disease, and now it is known how to battle against it with so much of its hidden mystery revealed.

In memory of the thousands who died at Norfolk and Portsmouth, and conscious of the security of a sure knowledge of how to prevent the disease, there are hosts who feel grateful for the devoted labors of that medical officer of the United States Army, Walter Reed, and his co-workers, who bestowed upon posterity a priceless knowledge of how this disease may be combated.

Enlarge page photos in browser

* * * * * * * * * *

Archival material for this file is provided by:

John G. “Jack” Sharp resides in Concord, California. He worked for the United States Navy for thirty years as a civilian personnel officer. Among his many assignments were positions in Berlin, Germany, where in 1989 he was in East Berlin, the day the infamous wall was opened. He later served as Human Resources Officer, South West Asia (Bahrain). He returned to the United States in 2001 and was on duty at the Naval District of Washington on 9/11. He has a lifelong interest in history and has written extensively on the Washington, Norfolk, and Pensacola Navy Yards, labor history and the history of African Americans. His previous books include African Americans in Slavery and Freedom on the Washington Navy Yard 1799 -1865, Morgan Hannah Press 2011. History of the Washington Navy Yard Civilian Workforce 1799-1962, 2004.

https://www.history.navy.mil/content/dam/nhhc/browse-by-topic/heritage/washington-navy-yard/pdfs/WNY_History.pdf

and the first complete transcription of the Diary of Michael Shiner Relating to the History of the Washington Navy Yard 1813-1869, 2007/2015 online:

https://www.history.navy.mil/research/library/online-reading-room/title-list-alphabetically/d/diary-of-michael-shiner.html

His most recent work includes Register of Patients at Naval Hospital Washington DC 1814 With The Names of American Wounded From The Battle of Bladensburg 2018,

https://www.history.navy.mil/research/library/online-reading-room/title-list-alphabetically/r/register-patients-naval-hospital-washington-dc-1814.html

The last three works were all published by the Naval History and Heritage Command. John served on active duty in the United States Navy, including Viet Nam service. He received his BA and MA in History from San Francisco State University. He can be reached at sharpjg@yahoo.com