Dartmoor Prison 1815

HM Dartmoor Prison and the War of 1812

by John G M Sharp

Introduction

Today most people remember HM Dartmoor Prison, if at all, either from having read or likely seen film versions of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Hound of the Baskervilles and Charles Dickens' Great Expectations with desperately fleeing murderer Abel Magwitch. For much of its long history, this prison became a byword for despair.

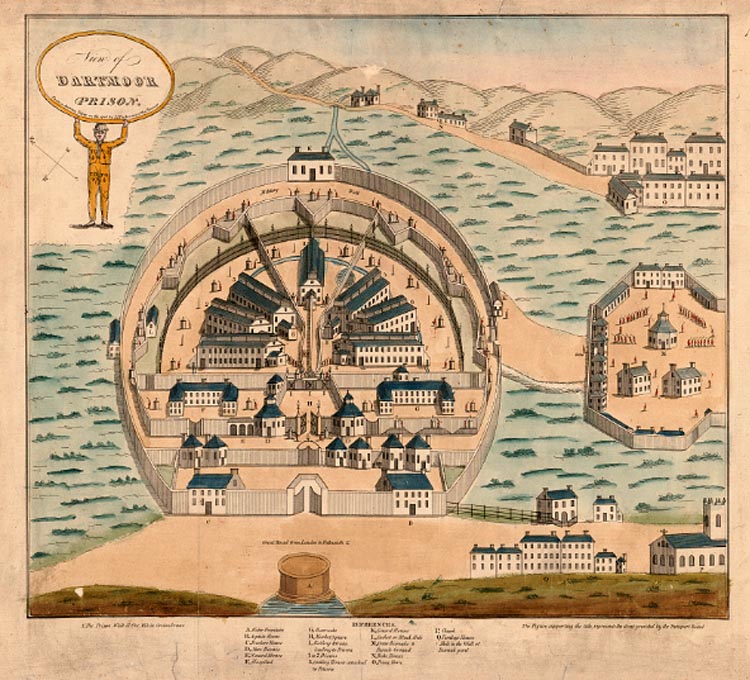

From the spring of 1813 until March 1815, the newly constructed (1809) HM Dartmoor Prison dominated the vast Devon landscape and held American seafarers in poor conditions. The prison complex was located 1,430 feet above sea level and surrounded by two high granite walls which govern a large area of the treeless ancient moorland, cloaked in fog or swept by winds and driving rain.1 During the course of the War of 1812, the prison held 6,553 American prisoners of war.1. Guyatt, Nicholas, The Hated Cage: An American Tragedy in Britain's Most Terrifying Prison (Basic Books, New York, 2022), p. 9; Hickey, Donald R. The War of 1812: A Forgotten Conflict (University of Illinois, Chicago, 2012), p. 312.

The majority of those held in Dartmoor Prison were the crews of American privateering vessels. These seafarers manned privately owned merchant ships that, in wartime, that were armed by their owners and licensed by the government to attack the maritime trade of the enemy. Privateers profited by the sale of ships and cargoes they captured. The privateering business involved ownership consortiums to split investment costs and profits or losses, and a group contract to incentivize the crew, who were paid only if their ship made profits. A sophisticated set of laws ensured that the capture was “good prize,” and not fraud or robbery.*

* Leiner, Frederick C., Yes, Privateers Mattered, March 2014, Naval History Magazine, Volume 28, Number 2.

American privateering vessels hunted British ships leaving United Kingdom ports and drove-up insurance rates for merchant ships sailing from the ports of Liverpool to Halifax by 30%. Throughout the war American privateers captured and harassed British commerce in the Irish Sea where insurance rates for vessels trading between England and Ireland rose and unprecedented 13%. As a result by 1814 the British Navy was forced to convoy merchant ships. American privateers in search of prey operated around the globe particularly in the Caribbean. Such vessels usually fled from the larger better armed British war ships, and when unable to escape often surrendered. On occasion however they could be formidable opponents.

The second category of prisoners were impressed (forcibly conscripted) American merchant seaman. Among these were sailors discharged from British vessels that refused to swear allegiance to the King and or continue in his service.2, 32. Guyatt, p. 12. Taylor, Alan, The Civil War of 1812 American Citizens, British Subjects, Irish Rebels and Indian Allies (Vintage Books, New York, 2010), pp. 364-365.

3. For an estimate of American seamen pressed into the Royal Navy during period 1793-1812, see "The Misfortune to Get Pressed 1793-1812." Joshua J. Wolf. Wolf estimates a total of 15,835.

https://scholarshare.temple.edu/bitstream/handle/20.500.12613/4048/TETDEDXWolf-temple-0225E-12189.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=yLastly but in many ways most importantly the 250 U.S. Navy sailors in Dartmoor Prison. The first of these arrived with the crew of the Brig USS Argus in September and October 1813.

This article comprises a brief overview of Dartmoor Prison during years 1812-1815, with a discussion of the differing reception and treatment afforded each category of Americans imprisoned therein during the course of the war.

John G. M. Sharp 24 November 2022

Acknowledgements

This history would not be possible without the many scholars who have begun to reexamine the history of the War of 1812, and to the libraries and librarians on both sides of the Atlantic who have carefully catalogued and preserved the naval and maritime records and documents this article is based on. Much of this present article is based on my research in from the British National Archives, General Entry Books of American Prisoners of War at Dartmoor. Today this splendid collection is one of our best and most unique sources starting pointfor information about the lives of ordinary American sailors imprisoned during the War of 1812. I have supplemented this with additional information found in Seaman’s Protection Certificates, United States Navy payroll and muster documents and contemporary newspaper accounts, all found in the National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, DC.

All historians depend on and benefit from the work of others who have gone before. First, I owe grateful thanks to Professor Nicholas Guyatt whose recent (2022) The Hated Cage: an American Tragedy in Britain's Most Terrifying Prison, brilliantly narrated and synthesized voluminous maritime and prison records into a coherent and fascinating history and yet still found time to answer my many questions.

A special thanks to my friend Donna Bluemink for her editorial help, insightful assistance and kind advice.

In the course of my research, I have utilized the late Ira Dye’s wonderful Prisoner of War Data Base numerous times. Captain Dye compiled a database of more than 17,000 prisoners of war taken during the War of 1812, now hosted by the USS Constitution Museum online https://ussconstitutionmuseum.org/ira-dye-prisoner-of-war-database. His extensive data base, research and insights contributed greatly to my understanding of American seafarers at Dartmoor Prison.

I also found Simon P. Newman’s (2003) splendid Embodied History: the Lives of the Poor in Early Philadelphia insightful. Like the great E.P. Thompson, Newman has chosen to write with care, respect and empathy about the lives of the working class. Newman was my model for the use of the Seaman's Protection Certificates (issued to American seamen from 1796-1818) to examine the lives of American seamen. Like Newman, I found these documents reveal these mariner’s lives were often harsh, dangerous and at risk of injury or death loomed ever large.

My gratitude and appreciation has grown for the website War of 1812 Privateers https://www.1812privateers.org/index.html. This site hosts a wide body of information about both American and British privateers with listings and explanations of American prisoners of war held in the United Kingdom plus British subjects held in the United States.Impressed Seafarers in HM Dartmoor

Impressment, colloquially "the press" or the "press gang", is the taking of men into a military or naval force by compulsion with or without notice.4 Many of the impressed sailors were Americans citizens taken off merchant vessels in Britain and foreign ports. For example, in Liverpool harbor on 3 November 1813, the Royal Navy forcibly detained seven American seamen. As they refused to serve in the British Navy, they were held in Dartmoor Prison until 26 April 1815.5

4. Hickey, Donald R. The War of 1812: A Forgotten Conflict. ( Urbana; Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1989), p. 44.

5. Dartmoor General Entry Books for American Prisoners of War, ADM 103/87, 88, 89, 90 and 91 British National Archives, see Dartmoor prisoners numbers 757-763.

British officers inspect a group of American sailors for impressment

into the British navy, ca. 1810, drawing by Howard Pyle.While the Royal Navy impressed American merchant sailors, the majority of those forcibly conscripted were actually citizens of Great Britain and other countries. Those liable to impressment were "eligible men of seafaring habits between the ages of 18 and 55 years.

Message in a bottle, William Banks, an impressed American seaman, pleas for help

In July 1813 a stroller forwarded a message he had found in a bottle by the Thames River addressed to James Banks at Hampton, Virginia, regarding his brother William Banks, a seaman on the HMS Ramillies. The HMS Ramillies was a 74-gun third rate ship of the line of the Royal Navy, launched on 12 July 1785. In August 1812, Sir Thomas Masterman Hardy had taken command of Ramillies. Commodore Hardy (later Vice Admiral) had fought with Admiral Nelson at the Battle of Trafalgar.

On receiving the letter James Banks about his brother William, sent a letter requesting the assistance to Congressman Thomas Newton and another to American Representative in London, James Mason requesting their assistance to secure William Banks a new seaman’s protection and his release.6

6. United States War of 1812 Papers 1789-1815 of the Department of State, 1789-1815; General Records of the Department of State, Record Group 59; National Archives, Washington, DC, see p. 91.

James Banks in his 5 July 1813 letter expressed his surprise to Congressman Thomas Newton about the letter "which came …in such a miraculous way".7

7. Thomas Newton Jr. (1768 -1847) was a United States Congressman from 1801-1833 representing the Hampton, Virginia, area.

Congressman Newton in his 10 July 1813 reply assured James Banks he was gathering the requisite information and concluded, "I am persuaded your exertions will be made to liberate an unfortunate American citizen from the fangs of British Myrmidons."

William Banks was born in Hampton, Virginia, about 1784 and was 29 years of age, standing 5’7½" and had been a seaman for nearly a decade. William’s message related he had been forcibly impressed into the Royal Navy, possibly while part of the crew of a merchant vessel in London. William Banks had been issued two earlier protection certificates. The first issued in London on 19 March 1806 at the American consulate and the other on 23 July 1806 in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, liting identifying marks of a foul anchor tattoo and a scar on his right hand. Banks was in the crew of HMS Ramillies then at Chatham, England. Banks desperately needed a copy of his protection certificate to prove his citizenship. William made his X on his certificate issued in Philadelphia in 1806, so another sailor probably helped write the message secured in the bottle. It is not known if any official efforts resulted in William Banks release.

John Howell Dartmoor Prisoner number 2721. Seaman John Howell was in the crew of a merchant vessel Eclipse when he was impressed into the British Navy in 1810. On 1 July 1813 Howell wrote to the State Department from the prison ship HMS Samson, begging for their assistance. In his letter he explained his "Protection" or "Seamen Protection Certificate", also "Sailor's Protection Paper", were taken. Protection papers provided a description of the sailor and showed American citizenship. Such papers were issued to American sailors to prevent them from being impressed on British men-of-war, during the period leading to and after the War of 1812.8 He claimed his papers identifying him as an American citizen had been taken and he needed a replacement to secure his release.

8. Sharp, John G. M. American Seamen’s Protection Certificates & Impressment 1796-1822. http://www.usgwarchives.net/va/portsmouth/shipyard/sharptoc/aspc&i.html

My last Protection was granted to my mother Mrs. Margaret Flinn, Philadelphi, in 1810 and was destroyed by the British the same year when I was placed on board the Polaris sloop of war at Smyrna out of the [merchant ship] Eclipse, captain Robinson. My marks: scar on my right hand, scar on my left foot, dark complexion, brown hair, pitted, smallpox, five feet eleven ½ inches high. Born in the City of Philadelphia.

John Howell, prisoner, on board HMS Prison Ship SamsonDespite his plea, John Howell spent the rest of the war as a prisoner, first at Chatham and later in Dartmoor. What he needed and desperately sought was his seaman's protection certificate; (see above) issued 16 May 1810. Howell was, as he stressed, an American citizen born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Like the majority of seafarers, Howell, by his X was probably not literate and had a fellow POW write his appeal to James Monroe. Sadly, neither the State Department nor Ruben Beasley, the American representative in London, were much help to POW’s. Beasley, in fact, was despised and burned in effigy by the prisoners.9

9. Guyatt, pp. 262-3.

Descriptions HM Dartmoor Prison 1812-1815

The majority of American seamen "were literate and able to express their thoughts and write about their experiences with a high degree of accuracy and articulation."10 In fact, the literacy rate may have been as high as 75 percent by the late eighteenth century and increased thereafter.11 Among the seaman confined to Dartmoor were some like Privateer Benjamin Franklin Palmer, who read books and novels and kept a diary.12 The bulk of the large prison population, though, read occasional newspapers and broadside for updates on the home front and the status of the war.13

10. James, Trevor, Prisoners of War At Dartmoor, American and French Soldiers and Sailors in an English Prison During the Napoleonic Wars and the War of 1812, (McParland & Company, London, 2013), p. 158.

11. Gilje, Paul A., To Swear Like a Sailor: Martime Culture in America, 1750 -1850 (Cambridge University Press, New York, 2016), p. 183.

12. Palmer, Benjamin Franklin, pp. 53, 106, 109, 135 and 142.

13. Guyatt, p. 198.

"Few Groups in our history are seen through such a romantic haze as are American seafarers of the early 1800’s"14

14. Dye, Ira, "Early American Merchant Seafarers." Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, vol. 120, no. 5, 1976, pp. 331-60.

George Little, Dartmoor Prisoner number 1367 was on the privateer Paul Jones when on 23 May 1813 she was captured by HMS Leonidas. Seaman George Little, was 25 years of age, born in Massachusetts and stood 5’6½‘’ in height, an experienced seafarer and was described in the Dartmoor entry book as "stout" (strong).

American Privateer Paul Jones Captured by HMS Leonidas 1813

Naval History and Heritage CommandGeorge Little’s narrative of his life both as sailor and prisoner during the War of 1812 is one of the best, especially his account of first viewing Dartmoor after a nine day march from the depot at Stapleton.

"A more miserable and wretched spot…"

This most fatiguing and harassing march was continued for nine days, during which many of the prisoners broke down, and were so entirely disabled that it became necessary to transport them in wagons. So unremitting was the vigilance kept over us (during the remainder of the march—after my project of escape had failed—that every effort to get away on the part of the prisoners proved ineffectual. At length, however, we arrived at Dartmoor; and I think I shall not overstep the bounds of truth, when I say, that a more miserable and wretched spot could not have been selected in the island of Great Britain, to erect a depot for prisoners of war, than this same barren heath presented. In vain may the eye exert its powers of vision to seek for shrub or verdure, and in vain may the mind contemplate a scene more melancholy than to see six thousand intelligent beings, confined in a circumference of about one half of a mile, strongly fortified, and encircled by walls, ditches and palisades, with cannon so planted as to command every part of the enclosure. It was nevertheless a relief to enter even this place, bad as it was, where we, might find rest for our wearied limbs and debilitated bodies. But if the location of Dartmoor inspires the mind with gloom at first sight, much more sensibly did I feel the horrors of confinement, when thrust into the interior. There were about six thousand American prisoners, who had been gathered from all the prisons and prison-ships in England.

Benjamin F. Palmer, Dartmoor Prisoner number 3944 was a seaman of the privateer Rolla who was captured on 10 December 1813 remembered the intake process thus:

October 5th 1814,

New entries to Dartmoor were mustered from a list of names and they give each one a hammock and bedding and we entered into the old prison kept for reception of prisoners. Our baggage soon arrived and everyone gets his things and away to bunk. We have some bread served out which is very acceptable, we sleep but very little being almost froze the prison being all open and our bone aching.

October 6th 1814

This morning the Clerk and Turnkeys came and measured us and one by one took down our completion, scars, place of birth, etc.15

15. Palmer, Benjamin Franklin, The Diary of Benjamin F. Palmer, Privateersman: While a Prisoner on Board English War ships at Sea, in the Prison at Melville Island and at Dartmoor (The Acorn Club, Connecticut,1914), pp. 102-103.

Charles Andrews, Dartmoor Prisoner number 381, also number 678, was a seaman on the privateer Virginia Planter which was captured off Nantes, France, on 18 March 1813, recollected his entry in Dartmoor Prison thus:

Thus we marched surrounded by a strong guard through heavy rain over a bad road, with only our usual scanty allowance of bread and fish. We were allowed only once to stop during the march of seventeen miles. We arrived at Dartmmor later on the after part of the day and found the ground covered with snow. Nothing could form a drearier prospect than that which now presented itself to our hopeless vision. Death itself seemed less terrible than this gloomy prison.16

16. Andrews, Charles, A Prisoners Memoirs of Dartmoor Prison (Printed for the author, New York, 1815), p. 10.

Benjamin Brown, Dartmoor Prisoner number 3598, a 21 year old clerk on the privateer Frolic arrived in Dartmoor on 30 September 1814. The Frolic was captured in the West Indies on 25 January 1814 so Brown and his shipmates had to endure a long Atlantic crossing to Portsmouth, England, where they were placed on board the HMS Sybille and transported to Plymouth. At Plymouth the captives were placed in an unnamed hulk, where the next morning they were mustered by name and placed under armed guard for the 19 mile march to Dartmoor Prison. Toward evening, after a cold and arduous march, Brown and his fellow seafarers entered into Dartmoor Prison. For their first night, the entrants were confined to a cold damp and dirty room. Brown was a keen observer, taking an anthropologist's interest in his surrounding and environment. Here, he describes the weather. Like many prisoners, Benjamin Brown found Dartmoor had some the worst weather on the Devon coast in terms of wind, rain and cold. As a consequence, prisoners confined to stone cells with open windows for long periods, suffered and died at high rates from respiratory diseases such as tuberculosis and influenza.

The situation of the prisons was a very unhealthy one, and great mortality generally prevailed among the prisoners. Situated as it was on a mountain said to be seventeen hundred feet above the level of the sea, in a climate proverbial as is the west of England for moisture of atmosphere, poorly paid and scarcely clad, immured in gloomy stone prisons, which a ray of sun scarcely ever penetrated, without glass in the windows to guard us against the cold and dampness, and no fires allowed in the prisons, we could not otherwise be unhealthy. The weather when except by mere chance it was fair was continually drizzling.16a

16a. 16a Brown, Benjamin Frederick, editor, Nathaniel Hawthorne, The Yarn of a Yankee Privateer, (Funk and Wagnalls Company, New York, 1926), pp. 422. First published as Papers of Old Dartmoor, U.S. Democratic Review, New York, in seven parts, January to September 1846

Perez Drinkwater, Dartmoor Prisoner number 937 was a lieutenant aboard the privateer Lucy, which was captured by the HMS Billerkin on 13 January 1813. The entry record for Drinkwater stated he was 25 years of age, 5’ 9" tall and described as "long haired". Letters from American prisoners in Dartmoor are rare, for as Drinkwater wrote, "I am compelled to smuggle this out of prison for they will not allow us to write to our friends, if they can help it". We are indeed fortunate to have the few Drinkwater was able to get past the guards.17

17. Felknor, Bruce, "A Privateersman's Letters Home from Prison" http://www.usmm.org/felknor.html

Dear Sally –

Royal Prison Dartmoor, Oct 12, 1814

It is with regret that I have to inform you of my unhappy situation,, that is, confined here in a loathsome prison where I have worn out almost 9 months of my Days; and god knows how long it will be before I shall get my Liberty again. . . . I cheer my drooping spirits by thinking of the happy Day when we shall have the pleasure of seeing you and my friends. . .

This same place is one of the most retched in this habited world . . . neither wind nor water tight, it is situated on the top of a high hill and is so high that it either rains, hails or snows almost the year round for further particulars of my present unhappy situation, of my strong house, and my creeping friends which are without number. . . .

. . . my best wishes are that when these few lines come to you they will find you, the little Girl [his daughter] my parents Brothers sisters all in good health I have wrote you a number of letters since my imprisonment here and I shall still trouble you with them every opportunity that affords me till I have the pleasure of receiving one from you which I hope will be soon. . . .

I am compelled to smuggle this out of prison for they will not allow us to write to our friends if they can help it. . . . So I must conclude with telling you that I am not alone for there are almost 5,000 of us here, and creepers a 1000 to one. . .

Give my Brothers my advice that is to beware of coming to this wretched place for no tongue can tell what the sufferings is here till they have a trial of it. So I must conclude with wishing you all well, so God bless you all. This is from your even [ever] dear and beloved Husband.

Josiah Cobb, Dartmoor Prisoner number 6632, a 19 year old seaman was captured in the privateer Prince de Neufchatel on 28 December 1814and was entered into Dartmoor Prison on 30 January 1815. Cobb was released on 5 July 1815

The next morning they were turned out into the yard, where we found a number of prison officials waiting for us. Each man was measured, and his height recorded in a book, he was critically examined and his face peered into to discover any marks by which he could be distinguished; this and complexion were likewise recorded. He was interrogated as to his age, place of nativity, the vessel he was captured in, and the station he filled on board. His answers were set down against his name. After we had been measured and interrogated each man received a hammock, bed, blanket, pillow, a bunch of rope yarn, a tin pot with a wooden spoon and to every sixth man a three gallon bucket.18

18. Brown, Benjamin Frederick, editor Nathaniel Hawthorne, The Yarn of a Yankee Privateer, Funk and Wagnalls Company, New York, 1926), pp. 161-167. First published as Papers of Old Dartmoor, U.S. Democratic Review, New York, in seven parts, January to September 1846.

As soon as dismounted from the wagon, the five of us were ushered into the clerk’s office, to have our names recorded and numbered according to seniority of entrance and ages, heights, and birth places noted down opposite our names. My number was 6632 which shows how many prisoners had preceded me to this dismal abode I was about entering, after having gone through with registering, a hammock and blanket were given to each "to be returned when released"…

The turnkey opened the portal in which we entered, and the ponderous door of bars and rivets was slammed in our rear… I stood, collected my sight and senses from the glare of the light and hum of many voices which burst upon me, the only conclusion I came to was that I had suddenly awakened from a disturbed dream which left me where I was, in reality in Pandemonium.19

19. Cobb, Josiah, A Green Hands First Cruise roughed out from the log book of memory of twenty five years standing Together with a residence of five months at Dartmoor Prison. By a Yonker (Baltimore, Cushing and Brother, 1841), pp. 1-6.

The General Entry Books of American Prisoners of War at Dartmoor Prison & What They Reveal

"The detailed personal information on these men recorded in the General Entry Books is the richest single source of data relating to early American seafarers"20 These prison records provide each prisoner’s number, name, ship, date and place of capture, rank, birthplace, age, physical description and details of discharge, death, or escape. Each of these follow a standard form which contained details of which ship captured the named prisoners, from which vessel, and when.

20. Dye, Ira.

General Entry Book of American Prisoners of War

at Dartmoor Prison, entry 1090 William BriggsTypes of Personal Information Collected

The personal information collected in the General Entry Book of American Prisoners of War at Dartmoor Prison is a treasure trove of data for historians and demographers. Prior to the invention of photography, this collection process insured every inmate had a "word picture" entered on record, see above.21 On entrance to Dartmoor Prison, all prisoners were assigned a prison number, then examined by the clerk who carefully recorded information regarding their background, physical characteristics, etc. For example: in the column nativity or place of birth, a review of these records reveal most of the American seafarers imprisoned in Dartmoor were native to either Boston, New York or Philadelphia. In the column "Stature", we get our best evidence regarding the average height of American seafarers. Based on the data collected by Ira Dye, the average height of crew of the U.S.S Argus was 5’5" in height.22 Dye found the mean height of 5,317 men 21 years or older in the Dartmoor prison sample was 66.85 inches or 5.57 feet.23 Scholar Simon P. Newman found a similar distribution of height in his study of Philadelphia seafarers 1798-1816, with a mean height of 66.4 inches. He also noted these "white mariners were, on average, a striking 1.7 inches shorter than white male recruits in the Continental army"24 Newman concludes such data demonstrated compelling evidence of the ubiquity of multigenerational poverty and poor nutrition.25

21. James, Trevor, p. 114.

22. Dye, Ira, The Fatal Crew of the Argus Two Captains in the War of 1812 (Naval Institute Press, Annapolis Maryland, 1994), p. 136.

23. Dye Ira, "The Height of Early American Seafarers 1812-1815," The Biological Standard of Living on Three Continents: Further Explorations in Anthropometric History, John Komlos editor ( Routledge, New York, 1995), p. 97.

24. Newman, Simon P. "Reading the Bodies of Early American Seafarers." The William and Mary Quarterly, vol. 55, no. 1, 1998, pp. 59-82, see page 65.

25. Newman p. 110.

For Those in Peril on the Sea

Even in peacetime, seafaring was and is one of the most dangerous occupations in the world. In the entry book column labeled "Marks", we find descriptions of prisoner’s scars and amputations, with the most common injuries to the extremities broken or missing fingers and injuries to legs feet and toes were commonplace.26 In this column we also find descriptions of birthmarks, knife and gunshot wounds, genetic defects such as moles and freckles. To this list the examiners entered marks left by diseas, such as small pox. Small pox (variola virus) was definitely the most common notation in this category.

26. Newman, p. 111.

President James Madison on 27 February 1813 signed the first major piece of vaccine legislation to combat smallpox, entitled "An Act to Encourage Vaccination", but the implementation was at best haphazard. During the War of 1812, the U.S. War Department ordered vaccination to prevent smallpox; the US Navy did the same. At Dartmoor growing concern about a possible outbreak of small pox led Royal Navy Surgeon Dr. George Magrath to begin a smallpox vaccination program in January 1815, but this was also too late as the virus had killed numerous prisoners.27

27. Guyatt, p. 246.

In column "Visage & Complexion", white sailors were described by facial characteristics "long" "oval" and "round face". Black sailors were listed as "Black", "Negro", and occasionally as Seaman John Berryman of Maryland, was a "Man of Colour". In all the General Entry Book of American Prisoners of War, Dartmoor U.K., 1813-1815, recorded names of 6,550 seamen, 955 of those prisoners were described as Black, 14 of which gave their place of birth as Africa.28

28. Dartmoor General Entry Books for American Prisoners of War, ADM 103/87, 88, 89, 90, and 91, British National Archives.

Privateers

During the War of 1812, both the British and the American governments used privateers. Prize money served as an important incentive encouraging men to serve at sea. This was true for the regular navy, and was even more significant for the men who signed aboard the more than 500 authorized privateers, sponsoring privately owned ships and commissioned by the government to capture enemy commerce in a form of legalized piracy.29

29. Gilje, Paul A., "Cruising for dollars: Privateers in the world of 1812" NPS Series: "The Luxuriant Shoots of Our Tree of Liberty:" American Maritime Experience in the War of 1812, National Park Service, https://www.nps.gov/articles/cruising-for-dollars.htm

The U.S. Congress declared that war be and the same is hereby declared to exist between the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and the dependencies thereof, and the United States of America and their Territories; and that the President of the United States is hereby authorized to use the whole land and naval force of the United States to carry the same into effect, and to issue to private armed vessels of the United States commissions of marque and general reprisal, in such forms as he shall think proper, and under the seal of the United States, against the vessels, goods and effects of the Government of the said United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, and the subjects thereof.

During the war, over 200 American privateering vessels were captured by the Royal Navy, and their officers and crews incarcerated at Dartmoor and other royal prisons. Despite these losses, privateers were essential to the American war effort, for they collectively captured and sunk as many as 2,500 British ships and which has been estimated as approximately $40 million worth of damage to the British economy.30

30. Tabarrok, Alexander (Winter 2007). "The Rise, Fall and Rise Again of Privateers" (PDF) The Independent Review. Vol. XI, no. 3., pp. 565-577, https://www.independent.org/pdf/tir/tir_11_04_06_tabarrok.pdf

Confinement and Escape

Dartmoor Prison, unlike many early nineteenth century English detention facilities, was purposely built in a remote isolated location, ringed by high stone walls and manned by hundreds of armed militia sentries. In addition, a rope ran around the entire circumference of the prison which was linked to a series of bells that quickly spread an alarm. Even if a determined prisoner made it beyond the prison walls, he would still have to traverse ten miles on foot over wild moorland and bogs, an area frequently beset with fog and chilling winds to reach the nearest town.31 Local residents turning in an escapee could expect a reward of a guinea.32 The typical punishment after a failed breakout was solitary confinement in a cachot (black hole) and reduced rations.33Yet, despite these daunting odds, scholar Nicholas Guyatt has tallied a total of twenty-four American prisoners of war successfully made their way to freedom.34

31. Guyatt, Nicholas The Hated Cage: An American Tragedy in Britain's Most Terrifying Prison (Basic Books, New York, 2022), p. 204.

32. James, Trevor, p. 75.

33. Guyatt, p. 205, and see James, pp. 53-53.

34. Guyatt, p. 208.

Dartmoor quickly acquired a formidable reputation as a terrifying prison. In June 1814, a group American prisoners of war confined in the prison ship HMS Nassau, after learning of their scheduled transfer to Dartmoor, drew their knives on sentries, then seized the jolly boat and pulled for the nearest shore. The group was quickly overtaken by Royal Marines from the HMS Nassau and other ship boats. During the capture three prisoners were wounded but all four returned to the ship.35

35. The Observer (London, Greater London, England), 26 June 1814, p. 3.

Dartmoor prisoner number 22, John Newell, a cook, on the privateer Tiger, was born in Africa. In the Dartmoor entry book he was listed as "Negro", and 37 years old, 5'4'' in height, "stout" (strong). Newell and the crew of the Tiger were captured on 8 Aug 1813. Newell was finally released 16 Mar 1815. He was the first black seaman captured in 1812 but by war's end there would be over 900 black men in Dartmoor.

HM Gibraltar prisoner number 48, John Newell. During the War of 1812, Great Britain used prisons throughout its vast empire in locations scattered around the world to temporarily incarcerate Americans. These prisons were located in the Bahamas, in Canada at Halifax, Nova Scotia and Quebec. Britain also maintained prison facilities on the island of Malta and another at Gibraltar, Spain. The attached entry confirmed that on 5 August 1813 John Newell and the crew of the Privateer Tiger were capturedby HMS Andromeda and subsequently delivered to HM Prison at Gibraltar. There Newell and his shipmates were kept locked up until they could be safely transported to England. Privateer John Newell is prisoner number 48, in the attached General Entry Book of American Prisoners of War at Gibraltar.

Richard Crafus, Dartmoor prisoner number 6303. Richard Crafus, aka "Richard Seavers", was a black seaman, who was born in Vienna, Maryland, about 1791. In 1814 he was working as a sailor aboard the privateer Requin when that vessel was captured by the HMS Venus off Bordeaux, France, in the river Garonne, on 6 March 1814.36 Credit for the capture of the Requin officially was assigned to the army of General Lord Arthur Wellesley, later Duke of Wellington.

36. "Capture of the Ship Requin in the Garonne by Mr. Ogilvie" Hansard House of Common’s Debates, 02 July 1823 , volume 9, cc1405-12.

Richard CrafusRichard Crafus had refused enlistment in the Royal Navy and first was imprisoned in the hulks at Chatham before being sent on to Dartmoor.37 His Dartmoor entry #6303 described him as 6’3¼", stout (strong) with a round face, black complexion, black hair and black eyes.38, 39 Standing well over six feet tall and a trained boxer, he literally towered above his contemporaries. In the writing of former prisoners, it is apparent Crafus was an object of both awe and fear. He quickly became the leader of Dartmoor’s black inmates after the white American prisoners successfully petitioned the British prison administration for segregation.40 A recent examination the General Entry Books of American Prisoners of War at Dartmoor by scholar Nicholas Guyatt, found "Eight Hundred and Twenty - Nine Sailors of Color had been entered into the register by the end of October 1814."41

37. Fisher, David Hackett, American Founders: How Enslaved People Expanded American Ideals (Simon & Schuster, New York, 2022), p. 671.

38. Lipke, Alan Thomas, "The Strange Life And Stranger Afterlife Of King Dick including His Adventures in Haiti and Hollywood With Observations On The Construction Of Race, Class, Nationality, Gender, Slang Etymology And Religion" (2013,. Graduate Theses and Dissertations http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/453

39. Jones-Minsinger, Elizabeth, “Our Rights Are Getting More & More Infringed Upon”: American Nationalism, Identity, and Sailors’ Justice in British Prisons during the War of 1812.” Journal of the Early Republic, vol. 37, no. 3, 2017, pp. 471–505, see p. 490.

40. Guyatt, pp. 180-184.

41. Guyatt, p. 219.

After the prison division, Crafus became known as “King Dick”, the leader of Prison Number Four. According to memoirs written by white inmates, he ruled strictly and fairly. This meant that life in Prison Number Four was perceived as more desirable than elsewhere in Dartmoor Prison. Because King Dick allowed whites to transfer to Number Four, many whites did so. In 1815, the British released the American prisoners of war.

Following the peace, Richard Crafus went to Boston where he taught boxing from 1826 through 1835. He also served as an auxiliary in the police department. "He led an annual procession around Boston Common on Election Day, after which he gave a patriotic speech." He died on 12 February 1831 in Boston “of a severe cold induced by exposure” possibly influenza.4242. The Liberator, (Boston, Massachusetts), 12 February 1831, p. 27.

Escape from Dartmoor Prison

General Entry Book of American Prisoners of War at Dartmoor, Admiralty Records (ADM) no 929,

James McFaddenJames McFadden, Dartmoor prisoner number 929 became the first American to escape Dartmoor Prison. McFadden was born in New York, was recorded as age 26 and 5’11½". At the beginning of the war, McFadden was 2nd mate aboard the privateer Brig General Armstrong. The vessel was armed with seven guns including a 42-pounder Long Tom cannon and had a crew of 90 men. The General Armstrong turned into a highly successful privateer and captured multiple ships. One of these was the British ship Fanny from Pernambuco bound to Liverpool, with a valuable cargo of cotton, coffee and tallow, etc. The General Armstrong engaged the Fanny forty minutes before she struck her colors; the Fanny had six men severely wounded and one killed, her hull rigging and sails were considerably cut up, but the Armstrong received no damage.

Privateer General Armstrong4343. “The Privateer Brig General Armstrong, Captain S. C. Reid Commander, which fought a thrilling battle in the Harbor of Fayal" The artist unknown, date unknown, image from George Coggeshall, History of the American Privateers, and Letters-of-marque, During Our War with England in the Years 1812, 1813 and 1814, (G P Putnam, New York, 1861), p. 273.

McFadden was named prize master (acting captain) with instructions to take her to a safe port or harbor. Unfortunately, HMS Sceptre recaptured Fanny on 12 May and returned, arriving off Skelling Rock on the west coast of Ireland on 8 June. A Russian man-of-war ran afoul of Fanny in the Downs on 18 June, causing the Fanny to lose a mast and suffer other damage. She arrived in Gravesend on 24 June. She finally arrived in Liverpool on 26 September. McFadden and the crew were transferred to HM Dartmoor.

In September of 1814, British boarding parties from nearby royal ships attacked the General Armstrong while she lay in a neutral port in the Azores. Ultimately, the privateer was abandoned by her crew, but the British had suffered close to 200 casualties compared to only nine for the United States. "The Americans," said an English observer, "fought with great firmness, but more like bloodthirsty savages than anything else, British officials were so embarrassed by their losses in this engagement that they refused to allow any mail on the vessels that carried their wounded back to England, see Hickey, p. 219.

Escape of American Prisoners of War on the road to Dartmoor

London, June 30, 1814American prisoners of war under escort to Dartmoor were on occasion lightly guarded and, as in this case, were able to break free of their confinement while lightly guarded. Taunton is about sixty miles from HM Dartmoor Prison. The prisoners were housed in the Old Angel Inn (probably in a barn) which was located in the middle of the town of Taunton, on main road to the West of England and Dartmoor.

Saturday a detachment of American prisoners arrived at Taunton on their route to the depot at Dartmoor. In the middle of the night they contrived, by taking up the flooring of the room in which they were confined at the Old Angel Inn, and digging down to admit their escape. Twenty-seven succeeded in getting out, of whom eleven only have been retaken.44

44. New England Palladium, 9 September 1814 (Boston, Massachusetts), p. 3.

John Wilson, Dartmoor Prisoner number 1729. Wilson escaped while on the arduous 17 miles uphill march from HM Plymouth Prison to HM Dartmoor Prison. He and the other American prisoner were just off ship and had not marched for a while.45 Many of the men were shoeless and poorly clothed as they tread the stony path. Wilson had been captured on the privateer Governor Garry while serving as a seaman on 31 May 1813. He is described as 20 years of age and born in Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania.

45. Bolster, W. Jeffrey, Black Jacks: African American Seamen in the Age of Sail (Harvard University Press, Cambridge Massachusetts, 1997), p. 104.

General Entry Book of American Prisoners of War at Dartmoor, Admiralty Records (ADM) no 6523

Caleb RichmondCaleb Richmond, Dartmoor Prisoner number 6523. Caleb Richmond a 34-year old black seafarer was born in Pennsylvania. He was in the Royal Navy at the outbreak of the War of 1812 but voluntarily gave himself up as not willing to fight his own country. Richmond was first placed in the Chatham hulk HMS Ganges and subsequently transferred to Dartmoor Prison. On 1 June 1815 Richmond became the first black prisoner to escape Dartmoor Prison.

John Langford, Dartmoor Prisoner number 774, the Great Escapist.

On 26 October 1813, John Langford, an experienced sailor, age 25, standing 5’5’’ and born in Somerset New Jersey, had taken a position aboard the privateer Betsy which was captured by HMS Eurotas off the island of Ushant near the Southwestern end of the English Channel.46 The Eurotas, launched in 1813, was a 35-gun British frigate. After capture, Langford and the rest of the crew were first takent HM Prison Plymouth and then on to HM Dartmoor as prisoner #774.46. General Entry Book of American Prisoners of War at Dartmoor, Admiralty Records (ADM) no. 774, British National Library.

Langford made his first try at fleeing Dartmoor Prison on the morning of 16 October 1814 and his second attempt two months later on 8 December 1814. Following each attempt Langford was placed in the prison cachot (a dungeon or black hole) for a number of days as punishment. Here in a cold, dark, confined space and on reduced rations, he plotted his next attempt.47His final and successful escape was on 3 February 1815.

47. Palmer, p. 176.

Reward Notice, for Swaine and Grasshon, Morning Chronicle (London, Greater London, England),

8 November 1814Thomas Swaine, Dartmoor Prisoner number 2971. Swaine was a 29-year old officer of the privateer Wily-Reynard, a schooner from Boston. Early in the war, the Wily-Reynard was highly successful taking three ships, two brigs and four schooners as prizes.48 The Wily Reynard had a crew of 6o men and carried 14 guns and was captured on October 11, 1812, by HMS Shannon.49Thomas Swaine escaped on 3 November 1814 with fellow prisoner Lieutenant Richard Grasshon.

48. Kert, Fae M. “Privateering Prizes and Profits: The Private War of 1812” The Routledge Handbook of the War of 1812, editors Donald R. Hickey and Connie D. Clark (Routledge, New York, 2015), p. 65.

49. McClay, Egar Stanton, A History of American Privateers (D. Appleton and Company, New York, 1899), p. 234.

Lt. Swaine has been described by one historian as "a murderous thug".50 A reward notice for him and another prisoner was quickly issued, headlined “Escape of American Prisoners of War”, with the Navy offering a Five Guinea reward.51 A memorandum copied onto Swaine’s Dartmoor Prison entry stated “this man reported by order of Sir R. Brieden on being account of murdering [August 1812] an old man [Francis Clements] in a most wanton and cruel manner on a small island a little to the Westward of Halifax N.S. called Sheep Island.”52

50. Emmons, George Foster, The Navy of the United States 1775-1853 (Gideon & Co, Washington, DC, 1853), pp. 196, 200-201.

51. Kert, Faye M. Privateering Patriots and Profits in the War of 1812 (Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, 2015), p. 104.

52. Morning Chronicle (London, Greater London, England), 8 November 1814, p. 1.

As a lieutenant of the Wiley-Reynard, Thomas Swain had overseen this shocking raid which the laws of war and his own commission strictly forbade him.53, 54 British anger was such that Lt. Swaine was the subject of a letter from Lieutenant Governor Sherbrook to Lord Bathurst excoriating his conduct and flagrant violation of law and urging his punishment. The Wiley Reynard was later captured by the 38 gun frigate HMS Shannon. Following his capture Lt Swaine was first incarcerated in the HM Melville Island Prison and subsequently moved to HM Dartmoor Prison.55

53. General Entry Book of American Prisoners of War at Dartmoor, Admiralty Records (ADM ) no. 2971.

54. Guyatt, p. 208.

55. Kert, pp. 104-105.

Two of the Youngest Prisoners

General Entry Book of American Prisoners of War at Dartmoor, Admiralty Records (ADM) Nathaniel Lee, prisoner, # 2657,

Nathaniel Lee, Dartmoor Prison number 2607. Nathaniel Lee was rated a "Boy” or young seaman in training. He was born in Marblehead, Massachusetts, and served on a privateer, the schooner Growler. The Dartmoor Entry Book recorded Lee as 12 years of age, and his height 4'2'', making him the youngest and shortest sailor.The Growler, under Captain N. Lindsey, had had a relatively successful cruise, having taken the ship Arabella, a brig, the schooner Prince of Wales, and the brig Ann. On 7 July 1813, the Growler's luck ran out when she was captured by the HMS Electra. The Electra with 18 guns overtook the Growler after a six-hour chase. In a quick short fight, the privateer Growler was no match for a Royal Navy schooner as she had only one long 24-pounder gun and four 18-pounder guns. After capture, the crew of the Growler was delivered to Chatham, England, where they were placed in (prison ship) the HMS Freya. Prison hulks like the Freya were decommissioned naval vessels that authorities used as floating prisons in the 18th and 19th centuries. Due to the large number of prisoners of war and few purpose-built prisons, converted ships or hulks, were extensively used in England to house prisoners of war. During the War of 1812, boys like Nathaniel Lee ranging in ages 12-16, often served in U.S. Navy vessels and privateers.

John Seapatch, Dartmoor Prison number 5889, was twelve years old and was rated as Boy. He was in the crew of the privateer Harlequin when she was captured by the British. Harlequin was a schooner of 232 tons, and her captain Elishu D. Brown, she had 10 guns and about 117 men. She sailed from Portsmouth, cruising, and was out only four days when she was captured October 23, 1814, by HMS Bulwark, a 50-gun ship of the line. John Seapatch was born in Massachusetts and according to Dartmoor prison records was 4 feet, 8 inches tall with grey eyes and a fair complexion. Seapatch was supplied with bedding at the prison in December 1814 and barely two months later died on 7 February 1815 of Tabes Mesenterica a form of tuberculosis.

An Old Salt and a Black Patriot

John Kelley, Dartmoor Prison number 3756, a seaman of Marblehead, Massachusetts, was 62 years of age and part of the crew of the privateer Alfred when she was captured by the sloop HMS Epervier, Commander Richard Walter Wales, on 23 February 1814 off the coast of Newfoundland. The brig Alfred, mounted 16 long 9-pounder cannon but surrendered without a fight. John Kelley and his shipmates were later transferred to Halifax, Nova Scotia, and subsequently taken to HM Dartmoor Prison. Kelly died of anascara condition in which kidneys no longer function and the body retains too much fluid.

Engraving of Henry Van Meter,

Harper’s Magazine October 1864Henry Van Meter, Dartmoor Prison number 5859. Henry Van Meter was born into slavery approximately 1766. His enslaver was General Thomas Nelson, governor of Virginia. Henry Van Meter fought at the Battle of Fallen Timbers in 1794 with General Anthony Wayne. He escaped his enslavers and in his forties, with the help of some Philadelphia Quakers, taught himself to read and write. “At some point between 1805 and 1814, when he was anywhere between forty and fifty years of age, Henry Van Meter decided the next chapter of his extraordinary life would take place on the ocean.56 During the War of 1812, he sailed aboard the Baltimore privateer Lawrence. When his ship was captured by the British, he spent time as a prisoner at the infamous Dartmoor Prison where he saw the infamous Dartmoor Massacre. Henry Van Meter died on February 14 1871 and is buried in Mt Hope Cemetery, Bangor Maine.

56. Guyatt, pp. 22-23.

Tattoos

General Entry Book of American Prisoners of War at Portsmouth

In the early Navy and merchant marine, tattoos were inked on ship. There is also evidence for American prisoners receiving tattoos at Dartmoor.57 On a man-of-war it is called tattooing or pricking. Novelist Herman Melville who served aboard whaling vessels and the frigate USS United States recounts the practice of “pricking” or tattooing aboard that vessel in 1844.

57. Gilje, Paul A., p. 261.

Some tattooists, or prickers, were celebrated in their way as consummate masters of the art. Each had a small boxful of tools and coloring matter; and they charged so high for their services that at the end of the cruise they were supposed to have cleared upward of four hundred dollars. They would prick you to order: a palm-tree, or an anchor, a crucifix, a lady, a lion, an eagle, or anything else you might want.”58

58. Melville, Herman "White Jacket or the World in a Man-of-War G", editor Thomas Tansselle (Library of America: New York 1983), p. 525.

Scholar Ira Dye summarized his findings: that the majority in the HM Dartmoor Prison Entry Books and Seaman Protection Certificate's descriptions of tattoos were of the sailor’s initials or his loved ones. Next in popularity were nautical symbols, e.g. anchors, ships and the seven stars. Ira Dye found about 6% of U.S. seamen were tattooed during the War of 1812. The first page of General Entry Book of American Prisoners of War Portsmouth (see above) entry numbers 1-10 has three sailors as “marked”, aka tattooed. They are:

No.1 Joshua Paine, “mark of a coconut tree, right arm”

No. 6 Peter Evan, “B. R. marked on left arm”

No. 9 Celeb Daymen, “marked with 7 Stars, left arm”

Caleb Daymen’s tattoo represented the seven stars composed of Rigel, Betelguese, Bellatrix, Mintaka, Alnilam, Alnitak and Sapih. The seven stars were in use before the advent of the Global Navigation Satellite System (GNSS) when seafarers looked to find Orion as a navigation aid. These are some of the brightest stars in the night sky, and were and are used to assist a sailor locating Orion to fix a positon and return home safely.

Samuel Wessel, Dartmoor Prisoner number 340. Seaman Samuel Wessel’s, entry notes include he was seaman, age 20. In the column “Marks” the Dartmoor clerk wrote "His Mothers Mark, Left Arm". In 1813 the word “tattoo” was not commonly used.59

59. Dye, Ira " Seafarers: A Profile, 1812, Prologue" Journal of National Archives and Records Administration, 5 (Spring 1973): 10. 4.

A Black Hero of the War of 1812

Jesse Williams, Dartmoor Prisoner number 3319. Jesse Williams was born in Pennsylvania in 1772 and enlisted on the USS Constitution in August 1812. Williams saw action aboard the USS Constitution during her historic victories against HMS Guerriere and HMS Java. Eventually, in 1813 he was transferred to the Great Lakes to serve under Commodore Oliver Hazard Perry. At the Battle of Lake Erie, Williams served on the USS Brig Lawrence and later the schooner USS Scorpion and was wounded during the battle. Williams was captured and taken to HM Dartmoor Prison and was finally released 3 July 1815. For his heroic service against the British squadron at Put-In-Bay, he was awarded $214.89 in prize money and eventually in 1820 a silver medal from the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania.

Seaman Jesse Williams, War of 1812 pension and detail of the payroll USS Constitution

April 1813 listing Williams* * * * **

John "Jack" G. M. Sharp resides in Concord, California. He worked for the United States Navy for thirty years as a civilian personnel officer. Among his many assignments were positions in Berlin, Germany, where in 1989 he was in East Berlin the day the infamous wall was opened. He later served as Human Resources Officer in South West Asia (Bahrain). On return to the United States in 2001, he was serving on duty at the Naval District of Washington on 9/11. He has a lifelong interest in history and has written extensively on the Washington, Norfolk and Pensacola Navy Yards, labor history and the history of African Americans. His previous books include African Americans in Slavery and Freedom on the Washington Navy Yard 1799 -1865, Morgan Hannah Press 2011 and History of the Washington Navy Yard Civilian Workforce 1799-1962, 2004.

https://www.history.navy.mil/content/dam/nhhc/browse-by-topic/heritage/washington-navy-yard/pdfs/WNY_History.pdf

and the first complete transcription of the Diary of Michael Shiner Relating to the History of the Washington Navy Yard, 1813-1869, 2007/2015 online:

https://www.history.navy.mil/research/library/online-reading-room/title-list-alphabetically/d/diary-of-michael-hiner.html

His most recent work includes “Register of Patients at Naval Hospital Washington DC 1814 With The Names of American Wounded From The Battle of Bladensburg” 2018,

https://www.history.navy.mil/research/library/online-reading-room/title-list-alphabetically/r/register-patients-naval-hospital-washington-dc-1814.htmlHe is currently working as a writer/adviser with Salt Marsh Productions, Animating History American Stories Brought to Life, in a production of “The Diary of Michael Shiner” set for release late 2022.

John served on active duty in the United States Navy, including Vietnam service. He received his BA and MA in History, with honors, from San Francisco State University. He can be reached at sharpjg@yahoo.com