Introduction: I first learned about the twenty-one female Army Arsenal employees who tragically lost their lives on 17 June 1864 in Washington D.C., while researching what became a History of the Washington Navy Yard Civilian Workforce 1799 -1962.1 As part of my research I walked the Congressional Cemetery and read the monument which recorded their names. However, it was not until I read the late Brian Bergin’s, excellent account (2012) The Washington Arsenal Explosion: Civil War Disaster in the Capital that I realized what these brave women endured.2

1. Sharp, John G., History of the Washington Navy Yard Civilian Workforce 1799 -1962 (Naval History and Heritage Command: Washington DC 2005),p.56., accessed 23 October 2024, https://www.history.navy.mil/content/dam/nhhc/browse-by-topic/heritage/washington-navy-yard/pdfs/WNY_History.pdf

2. Bergin, Brian, The Washington Arsenal Explosion: Civil War Disaster in the Capital (History Press, Charleston, S.C., 2012)

Female workers on the porch of Cartridge Manufactory, Laboratory, Washington Arsenal, 1863&4,

possibly Superintendent, Thomas B. Brown, center, with two boy sweepers. LOCThe profound impact of civilian deaths in wartime as explained by Drew Gilpin Faust in her magnificent This Republic of Suffering Death and the American Civil War greatly helped my understanding of the profound loss felt by family members and survivors.3

3. Faust, Drew Gilpin, This Republic of Suffering Death and the American Civil War (Vintage Books, New York, 2023)

John G.M. Sharp, 23 October 2023

Background: The American Civil War left the federal government with numerous vacancies as men either volunteered or were drafted into military service. Faced with an accrued labor shortage in 1862, some jobs at the United States Army Arsenal in Washington, DC, became open to women. Here on June 17, 1864, female workers, many of whom were young, working class Irish immigrants, were busy assembling ammunition cartridges at the Washington Arsenal manufactory, also known as laboratory, a U.S. Army installation (now Fort McNair) at the convergence of the Potomac and Anacostia Rivers. The women and girls employed there assembled bullets and were known as "chokers" and their work area the "choking room". On that tragic Friday, the manufactory was staffed with 108 women within the complex.

In 1864 these federal workers had little recourse or bargaining power. Women and girls seeking employment at the arsenal were offered ten hour days, scanty pay and dangerous work. There despite a history of tragic accidents, no safety regulations, no minimum wage and no child labor laws, they labored and endured. Among arsenal workers who died was the youngest worker Sallie McElfresh who was twelve years of age, and Lizze Brahler who shared their communal workbench was thirteen at the time of the explosion.4 Bridget Dunn a native of Wexford Ireland was 45.

4. Bergin, pp. 38-39, 44.

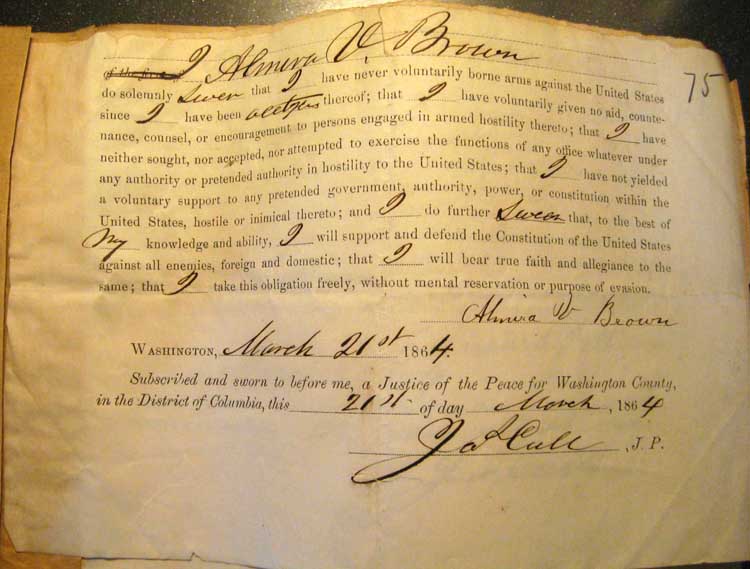

By an odd coincidence earlier that morning, the women had received a message thanking them for donating $170 towards a memorial for the 78 Allegheny Arsenal workers who were killed and over 150 injured in the explosion that occurred 0n 17 September 1862.5 Arsenal accidents tragically were a commonplace.6, 7 On 27 July 1861, at the nearby Washington Navy Yard Laboratory "an explosion took place in the Rocket House by which 3 men were killed and 2 injured".8, 9 With the start of the Civil War the federal government required all Washington Navy Yard employees including women such as seamstress Almira V. Brown working in the laboratory to sign a loyalty oath. 10

5. Mahr, Michael, Disaster at the Allegheny Arsenal , National Museum of Civil War Medicine, 26 September, 2022 https://www.civilwarmed.org/allegheny-arsenal/

6. Grady, John "An Explosion in Washington" New York Times, 15 June 2014 (Washington, District of Columbia), https://archive.nytimes.com/opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com/2014/06/15/an-explosion-in-washington/

7. Evening Star (Washington, District of Columbia, 18 June 1864,3rd edition),2

8. Sharp, John G. Washington Navy Yard Station Log Entries November 1822-December 1889 Naval History and Heritage Command, https://www.history.navy.mil/research/library/online-reading-room/title-list-alphabetically/w/washington-navy-yard-station-log-november-1822-march-1830-extracts.html9. Sharp, John G. History of the Washington Navy Yard Civilian Workforce 1799 -1962 (Naval History and Heritage Command: Washington DC 2005),4., accessed 12 September 2024 2024, https://www.history.navy.mil/content/dam/nhhc/browse-by-topic/heritage/washington-navy-yard/pdfs/WNY_History.pdf

10. Loyalty Oath, Alamira V. Brown, dated 21 March 1864

Almira V. Brown, seamstress, Washington Navy Yard, 21 March 1864, Loyalty OathThe female workers of the choking room certainly read and heard about these explosions as reported in the daily papers.11 Young Sally McElfresh’s certainly would have known about them from her father, John McElfresh, a painter who worked at the Washington Navy Yard since 1852.12 The women knew about the ever present risk involved, yet it did not deter them from their work for it was often their meager wage which helped pay for food and shelter. As a contemporary noted, these women "would rather earn a living salary at the risk of their lives then endure the indignities and hardships incident to many forms of female occupation".13

11. "Terrible Explosion at the Navy Yard" Daily National Intelligencer (Washington, District of Columbia, 29 July 1861, p. 3)

12. Bergin, p.38.

13. Dying for a Living Wage: Women’s Work during the Civil War A Philly History Podcast, 17 July 2023 https://foundinphiladelphia.com/dying-for-a-living-wage-womens-work-during-the-civil-war/

Following a deadly explosion on 27 June 1842 at the Washington Navy Yard laboratory, Michael Shiner, a free black painter who kept a diary, memorialized three fellow workers thus:

The death of Thomas Barry a gunner in the united states navy and David Davis they were killed in Washington navy yard by the explosion of a shell on the 27 day of June 1842 on Monday they were three Men within ten Months killed in Washington navy yard may the almighty grant that their souls are at rest for we are all neglectful of the things that are most [needful] for our souls welfare for when we part from each other for our daily occupation we don’t know whether we will ever Return in life again .14

14. Diary of Michael Shiner, Relating to the History of the Washington Navy Yard 1813-1869,Transcribed With Introduction and Notes by John G. Sharp, 2007 and 2015 Naval History and Heritage Command, June 1842, p. 81. https://www.history.navy.mil/content/history/nhhc/research/library/online-reading-room/title-list-alphabetically/d/diary-of-michael-shiner.html

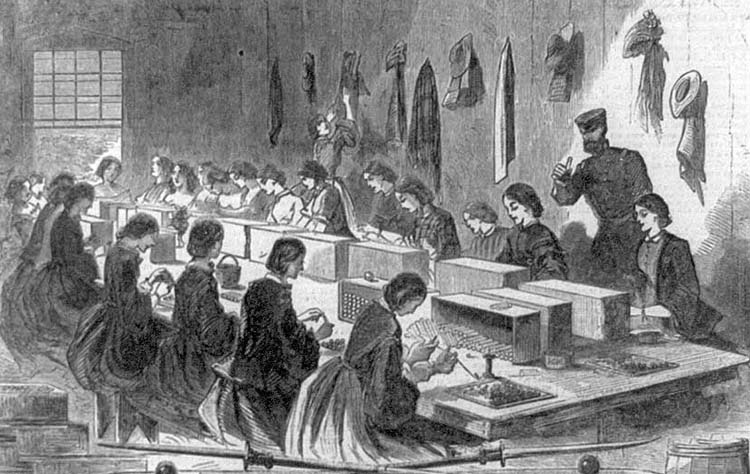

Young women and teenage girls were often selected for this dangerous task, as it was believed their smaller fingers better enabled them to pack the ammunition once it was assembled. At first young boys too were at given jobs in the laboratory, but they were thought to be inattentive and careless.15

15. Bergin, p. 42.

For those selected for employment in the laboratory choking room, the delicate work involved inserting a lead bullet into the powder filled cylinder, tying off the bullet end of the cartridge with a couple of rounds of thread and placing the closed cartridge into a wooden box that sat in front of each choker.16 A couple of boys were also employed to replace the cartridge boxes as they filled and to sweep sawdust and gun powder off the carpet. The carpet that covered the Arsenal’s floor was silent testimony to the danger the women and girls worked under. It was not there for ornament. It was there to prevent the possibility of minute sparks from the heels of shoes setting off a chain of explosions. Gunpowder inevitably spilled off the tables the workers were sitting at, and any spark on the ground posed the danger of destroying the Arsenal.17

16. Bergin, p. 42.

17. Bergin, p. 34.

Harpers Weekly July 1861 illustration shows women at the

Watertown, Massachusetts, arsenal filling cartridges. LOCThe weather that Friday was typical of Washington in summer: hot, oppressive and humid with temperatures approaching 100 degrees.18 Just before noon, red and white star pellets also produced used in fireworks that were drying on metal trays outside the women’s workspace ignited in the heat. The pyrotechnics flew into the air and one pellet entered a window left open for ventilation. It skidded across the worktable, igniting the cartridges being assembled and landed in a barrel of gunpowder. The ensuing explosion blew the roof off the building and fire engulfed the women all wearing (see image above) high collars and flammable cotton hoop skirts with long sleeves. Despite these dangers among all classes, the hoop skirt was popular fashion. The Washington Hoop Skirt Factory at the corner of 9th and D Streets ran regular advertisements in the Washington Evening Star proclaiming "Wanted Immediately 100 Ladies to manufacture Hoop Skirts" and a wage of four to five dollars per week.19

18. "Since the start of June midday temperatures in the nineties had been common and three-digit reports were discomfortingly frequent." Bergin, 114.

19. Evening Star (Washington, District of Columbia, 22 March 1862), 2

Many of the women died in the 17 June explosion. The press in lurid prose described how these female bodies were torn apart and covered with horrific burns.20 As heated cartridges on their assembly table subsequently exploded, they tore into the sitting workers. As John Grady has noted "their hoop skirts, worn at the insistence of government officials to preserve the women’s modesty and not distract the male workers, not only restricted their movement to escape, but held in place the fabric that so easily ignited."21 A local reporter for the Evening Star who covered the explosion and its aftermath recorded how the violation of an Arsenal regulation saved a life.

20. Zipardo, Jessica, This Grand Experiment When Women Entered the Federal Workforce in Civil War Washington, D.C. (University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill, 2017), pp. 164-165.

21. Grady, John, "An Explosion in Washington" New York Times, 15 June 2014 (Washington, District of Columbia), https://archive.nytimes.com/opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com/2014/06/15/an-explosion-in-washington/

A young girl employed in the laboratory was yesterday morning dismissed for laughing and talking in the room, contrary to rules. She bewailed the fact of her dismissal to an elderly friend who tried to comfort her by saying that it would perhaps all turn out for the best, but with no thought that the events of the day would so soon make her words true.22

22. Evening Star (Washington, District of Columbia, 18 June 1864, 3rd edition), 2

Arsenal Pay-Master and military storekeeper, Edward M. Stebbins, testified to the jury, he "did not think that any girls on the south side of the bench could have got up from their seats."23

23. Evening Star (Washington, District of Columbia, 18 June 1864, 3rd edition), 2

Those lucky enough to have survived the initial blast ran for the doors and windows, many with the bottoms of their hoopskirts ablaze.24As they rushed past terrified co-workers, their skirts would touch, resulting in a domino effect of flaming hoopskirts. The building was consumed in minutes and twenty-one women died.25 The District of Columbia coroner’s jury found, the Arsenal laboratory Superintendent, Thomas B. Brown, "guilty of the most culpable carelessness and negligence in placing highly combustible substances so near a building filled with human beings, indicating a most reckless disregard of life which should be severely rebuked by the Government." 26, 27

24. Evening Star (Washington, District of Columbia, 17 June 1864), 2

25. Bellamy, Jay "Fireworks, Hoopskirts—and Death" National Archives, Prologue Magazine, 2012, Volume 44, number 1, https://www.archives.gov/publications/prologue/2012/spring/arsenal

26. Weekly National Intelligencer (Washington, District of Columbia), 23 June 1864, p. 4.

27. "Terrible Explosion" The New York Times (New York, New York, 18 June 1864), p. 4.

By his own admission, Brown had considerable experience with munitions and had been employed at the Arsenal since 1841. At the inquiry Brown claimed he frequently dried them in the sun.28 The jury though specifically found Brown had laid out some red and white star flares to dry for the upcoming 4th of July celebrations, thirty feet from the laboratory building where the women worked. In addition to their proximity, they were set closely together which made the ignition of a single star likely to set off the rest. Given Brown’s long work experience with munitions and flares as a pyro technician, this was simply inexcusable. Around noon something set them off, most probably the intense heat of the sun sparked them. They then started to explode near the gunpowder.29

28. Evening Star, (Washington, District of Columbia 19 July 1914), p. 51.

29. Loomis, Erik, "This Day in Labor History: June 17, 1864", Lawyers Guns and Money blog, https://www.lawyersgunsmoneyblog.com/2017/06/day-labor-history-june-17-1864

The commandant of the arsenal, Major James G. Benton, arrived on the scene shortly after the explosion. Benton later notified his superior, General George D. Ramsey, by telegraph and followed up the next day 18 June 1864 with a letter describing what had occurred. This is partially transcribed below.

Gen G.D. Ramsay

Chief of Ordnance

Washington D.C

Sir,

In addition to my telegraph of the 17th instant informing you of the loss by fires of the main Arsenal building, I have to summit the following particulars with few exceptions. I am pained to say all of these young women were burned to death. The remainder, some eighty, in the building, escaped through the windows & doors without serious injury…

As soon as the alarm was given, the officers, soldiers and some of the unknown Arsenal [workers] promptly repaired to the spot and succeed in preventing the spread of the flames to the adjoining buildings. After this, firemen from the outside arrived and further assisted in putting out the flame, not however until the building was destroyed.

Major Stebbins, the Military Storekeeper, was in the choking room when the accident occurred and fortunately escaped. By his coolness & presence of mind, he assisted in helping many young to escape through the windows.

I have afforded every assistance in my power to the committee of workmen who were charged with the funeral and have endeavored to express the deep sympathy which your own and the War Dept. feel for the sorrowing friends. 3030. Benton to Ramsey, dated 18 June 1864, RG 153, Records of the Office of the Judge Advocate General, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington D.C.

Major Benton then suggested a cause for the explosion: "The accidental ignition of some stars which Mr. Brown the Master Laboratorian had prepared and laid out to dry in the sun, about 35 feet from the South end of the laboratory." (Benton estimated that there were approximately 160 pounds of white stars and 15 pounds of red.) The temperature outside the building had become severe enough as to cause the explosion of those stars containing Sulphur sending streaming pellets through the open window of the "choking" room, leading to the deaths of the women working there. Some 80 others in the building were able to escape through the open windows and doors of the adjoining rooms. He estimated that there were anywhere from 50,000 to 75,000 finished and unfinished carbine cartridges in the building at the time.

After praising Major Stebbins for his efforts in evacuating those who had survived the explosion, as well as the firemen who "from the outside arrived and further assisted in putting out the flames, not, however, until the building was destroyed," Benton then sought to exonerate himself.

"It may not be improper to state that while I am, as the commanding officer of the post, held responsible for its operations," he wrote, "I am compelled by the variety and extent of these operations to rely much on the care and judgment of the master workmen [Thomas Brown] to prevent accidents."

Thomas Brown had been in the laboratory business for 37 years, and it was in him that Major Benton had placed his trust. Although Benton offered no serious condemnation of Brown, he also failed to provide him with even the mediocre defense he had given during the coroner’s inquest the previous day.Federal law offered no compensation for those injured or killed on the job.31

31. Brown, Almira V., Claim of Almira V. Brown filed January 3, 1879, National Archives and Records Administration, pension applications. The pension application for Almira V. Brown was filed under the War Department’s provisions for widows and orphans claims for losses suffered during the War of the Rebellion (Civil War). Brown had claimed her husband Francis C. Brown, a laboratory worker, was killed on 27 July 1861 by accidental explosion in the navy yard rocket house. Her claim for pension was rejected on the basis her spouse was not military and no law covered civilian casualties even if the death occurred on the job.

The article below from the Weekly National Intelligencer, dated 23 June 1864, provided a harrowing account of both the explosion, the fire and coroner’s jury report findings that Arsenal Superintendent Thomas Brown was "guilty of the most culpable carelessness and negligence in placing highly combustible substances so near a building filled with human beings, indicating a most reckless, disregard of life which should be severely rebuked by the Government. Thomas Brown was in fact replaced as Superintendent by his assistant Andrew Cox, but neither the humiliation of the preventable disaster nor his demotion would be enough to drive Brown from the laboratory.32

32. Bellamy, Jay, Fireworks, Hoopskirts—and Death Explosion at a Union Ammunition Plant Proved Fatal for 21 Women Prologue Magazine, Spring 2012, Vol. 44, No. 1 https://www.archives.gov/publications/prologue/2012/spring/arsenal

Instead Thomas Brown stayed on as the arsenal pyro technician, through yet another explosion in 1865 that killed nine men, and a fire in 1866 that destroyed several building in the laboratory complex.33, 34

33. Bergin, pp. 92-93.

34. Washington Chronicle, (District of Columbia, Washington, 20 December, 1865 ) p. 4.

* * * * * *

TERRIBLE CALAMITY

EXPLOSION AT THE WASHINGTON ARSENAL

Weekly National Intelligencer (Washington, District of Columbia), 23 June 1864, p. 4.The Community were shocked yesterday (Friday) by one of those calamities that appall the mind by their suddenness and terrible consequences.

At ten minutes past twelve o’clock, the quarter of city adjacent to the United States Arsenal near the Four-and –a half street, was startled by an explosion, followed by a column of smoke rising from the Arsenal grounds. Persons hurrying to the scene found that the long building or shed called the laboratory, where shells are charged; was blown up, and was on fire. The alarm was given and the Hibernia steam engine and other machines were quickly rallied and set to work to quench the flames which were roasting the bodies of the unfortunate victims of the disaster. At twenty minutes past one the fire was extinguished, and some bodies and fragments of the bodies were taken out of the ruins.

The scene was horrible beyond description. Under the metal roof of the building were seething bodies and limbs, mangled, scorched, and charred beyond the possibility of identification. Most of those who skated – about two hundred and fifty persons, mostly female were employed in that building – had fled shrieking away. Some fainted and were with difficulty restored, and some after the first shock, returned to shriek over the fate of their companions;; while an agonized crowd of relatives rushed to the spot to learn the tidings of their daughters or sisters who were known to have been in the fated building.

Up to three o’clock eighteen or nineteen bodies had been taken from the ruins. They were so charred as to defy identification. The number could not be definitely ascertained, as the reader may know, when told that half a dozen of the bodies were put into a box about five feet square. Three women were taken out alive and placed in hospital. Their names are Sally Mc Elfresh, Annie Bache, (or Bates,) and Rebecca Huil. Miss Bates is so seriously burned that her recovery is doubtful

Sarah Gunnel escaped from the building, and, being terribly frightened, ran towards her home which is on Four-and a half street., Island, between Fifth and Sixth , but swooning away and died instantly it is supposed of fright.

Washington Arsenal 1864 explosion with remains of the laboratory building, LOCEXPLOSION AT THE WASHINGTON ARSENAL

Weekly National Intelligencer (Washington, District of Columbia), 23 June 1864, p. 4.We learned that four of the sufferers who were rescued alive from the burning ruins of the laboratory at the Arsenal on Friday died on Saturday, increasing the total number of deaths by that calamity to twenty-one, whose names are thus reported:

Susan Harris, a young girl, member of the Wesley Chapel: Eliza Lacy, Betty Breschnahan, whose husband is a soldier in Grant’s army; Miss Collins; Miss Yonson; Eliza Adams, daughter of a dealer in Centre Market; Miss Mc Elfresh, who was removed to her mother’s residence and died during Friday night; Ellen Roach; Anna Bache, died in hospital on Friday night; Joanna Connor; Kate Horan; Miss Dunn, Julia McElwen; Mrs. Tippett; Miss Murphy; Mary Burroughs; Rebecca Hull; Miss Brailor; Emma Baird; Mary Boroughs; and Ada or Willie Webster; which of the two is not certain, but that one of the sisters is dead appears beyond doubt.

The verdict of the inquest held by Coroner Woodward, in view of the bodies of the victims of this calamity:

Weekly National Intelligencer (Washington, District of Columbia), 23 June 1864, p.4Washington Arsenal, Washington D.C.: That on the 17th day of June the said Joanna Connor, or the body of the individual supposed to be a femal, came to her death by the explosion of the laboratory in which she was engaged in choking cartridges.. That the said explosion took place about ten minutes before 12 o’clock AM, and it was caused by the superintendent of the laboratory placing three metallic pans some thirty feet from the laboratory containing chemical preparations for the manufacture of white and red stars. That the sun’s rays operating on the metallic mass caused spontaneous combustion scattering the fire in every direction a portion flying into the choking room of the laboratory through the open windows, igniting the cartridges and causing the death of Joanna Connor. The jury is of the opinion that the superintendent, Mr. Brown [Thomas B. Brown] was guilty of the most culpable carelessness and negligence in placing highly combustible substances so near a building filled with human beings, indicating a most reckless disregard of life which should be severely rebuked by the Government.

* * * * * *

Monument for the victims of the 17 June 1864 explosion at the Washington, D.C. ArsenalThe monument is located in Congressional Cemetery, Washington, DC. The Arsenal laboratory was staffed with 108 women and girls (The youngest worker, Sallie McElfresh, was twelve years of age, and Annie Bache was but thirteen at the time of the explosion). In all twenty- one female laboratory workers, mostly Irish immigrants, died and many more were seriously injured in the explosion. The names of the dead, as inscribed are listed below:

Ellen Roche • Julia McEwen • Bridget Dunn • W. E. Tippett • Margaret Horan • Johanna Connors • Susan Harris

Lizzie Brahler • Margaret Yonson • Bettie Branagan • Eliza Lacey • Emma Baird • Kate Brosnahan • Louisa Lloyd

Mellisa Adams • Emily Collins • Mary Burroughs • Annie Bache • Rebecca Hull • Sallie McElfresh • Pinkey Scott

NEW BUILDING, NEW EMPLOYEES

Despite the appalling danger of arsenal work and the recent tragic deaths of twenty-one laboratory workers and many traumatized survivors, the manufacture of bullets and artillery shells was determined by the U.S. Army Ordnance Department to be of vital importance to national war effort.

On November 1864 the Evening Star carried news of the Arsenal Improvements and Major Benton stated, "The new laboratory of the Washington Arsenal is now in operation, some 60 female employees having been taken in on Monday." Benton made his selections amongst the large number of applicants for employment in the laboratory and "gave preference, very properly to the widows of Union soldiers, or the wives of soldiers in prison at Richmond and elsewhere." The Star reporter related, "Every care has been taken in the new building to provide against accident and the building instead being in an open hall is divided into compartment’s with heavily timbered division walls."3535. Evening Star, (Washington, District of Columbia ) 4 November 1864), p. 3.

* * * * * *

Copyright All rights reserved © USGenWeb Archives Project

http://www.usgwarchives.net/copyright.htm

http://www.usgwarchives.net/va/vafiles.htm