African

Americans, Enslaved & Free, at Washington Navy Yard

and Daniel and Mary Bell and the Struggle for Freedom

by John G. M. Sharp

Discipline and Resistance

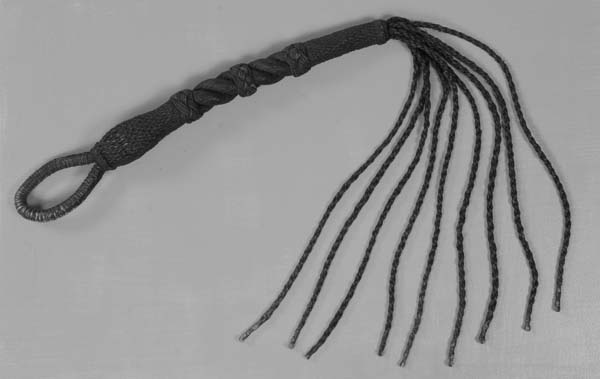

Slaveholder and master blacksmith, John Davis of Abel, like his compatriot Benjamin King, benefited directly from slaveholding and bluntly made the case for the employment of slave labor: "We found by long experience that Blacks have made the best Strikers in the execution of heavy work & are easily subjected to the Discipline of the Shop - & less able to leave us on any change of wages."112 Punishment for slaves ran the gamut from verbal reprimands, threats to inform the slaveholder of an infraction, hits with a boatswain's starter (a piece of rope, dipped in tar), whippings administered with a cat of nine tails, a multi-tailed whip. The "Cat" was made up of nine knotted thongs of cotton cord, about 2½ feet or 76 cm long, designed to lacerate the skin and cause intense pain. The final punishment was removal from the Yard rolls. All slaves were legal property, thus slaveholders normally administered discipline themselves. In 1810 Benjamin Henry Latrobe, engineer and architect, wrote to James Smallman, inventor and installer of the yard’s new steam engine:

Ben. King is forging the Crank. He has thought proper to alter his opinion and is making it the most tremendous lump of Iron, the Necks 4 inches in diameter, the squares 5 inches. He now thinks it too weak. He has been swearing and whipping his black Strikers at a terrible rate these two days past . . . 113

112 John Davis of Abel to Tingey, 15 March 1817, RG 45/M125, NARA.

113 Latrobe to James Smallman, October 5, 1810, Benjamin H. Latrobe Papers of Benjamin Henry Latrobe. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1984-1988, Volume II, p. 911.

Latrobe had come to hold King in low regard but there is no reason to think he is speaking metaphorically, for Michael Shiner writing a few years later recounted how infractions were handled. Speaking back to an officer, overstaying leave, fighting or getting drunk could result in "a starting," that being hit with the boatswain's starter. For more serious offenses, blacks were whipped with the cat of nine tails. Shiner recollected that Tingey‘s footman was taken to the Rigging Loft for punishment.

At the same time they wher a lad comerder tinsay foot man had been cuting some of his shines at the house on the 4 and they taking him down to the rigin loft that it give him a starting and they wher going to give me starting two.114

114 Shiner Diary p. 27.

We all hands of the ordernary men Wher cauled up in to the rigin loft to giv an acount of our selves captin Booth Wher present in the loft first lieutenant thomas crab and Sailing master edwar Barry who had prefered the charge against thomas pen captin Booth sais now thomas pen you are brought befor me for usin abusive and insultin language to an officer of this yard what have you got to say for your selve captin thee had kein a ben drinkin and if the said anything to Mr Barry out of the Way they are sorry for it and if thou pleases and if Mr Barry pleases to excuse the will never do so no more sire dont you no the danger of givin insolence to an officer Well tell the captin if thou please excuse me this time never do so no more sire Mr Barry reply i will excuse him this time captin now Thomas pen i will let you oft as Mr Barry has excuse you Now captin and Mr Barry the[y] is ten thousand times oblige to thou for letin [him] off captin Booth and first lieutenant crab sail Master edward Barry Boatswain David eaton turned their backs and laught and told Tom to go on now and behave your selves and never struck him a crack When pen got up to the ordernary house among the men are sais Tom pen by the powers of Mol kely didnt the(y) tell thou if ever thou let the[e] get into quaker sistom that thou would never Wip the[e] so Tom pen got clear of the cats [cat of nine tails] that day by talkin quaker to captin Booth and the rest of the officers.115

115 Shiner Diary, p. 20.

"Talkin Quaker" Michael Shiner, Diary, 1827, p.20, Michael Shiner relates how enslaved seaman, Thomas Pen, "talkin Quaker" artfully evaded, a severe flogging in the Rigging Loft, with "Cat of Nine Tails." Tom Pen was enslaved to Washington Thomas Navy Yard, Commodore Tingey's nephew, Lt. John Kelly USN. The cat o' nine tails, commonly shortened to “the cat”, is a type of multi-tailed flail that originated as an implement for severe physical punishment.

Floggings in the Navy were usually executed by the boatswain’s mate and witnessed by the entire crew. The offender was tied to a rail and whipped with the cat’s nine knotted cords. The cat is composed of nine lengths of tarred, braided hemp with ends lashed. The rope forming the stiff, thick handle is twisted, knotted, braided, and tarred, with a wrist loop at the top. The instrument measures 38 1/4 inches long overall, with the nine individual “tails” measuring approximately 18 inches each. In 1827, at Washington Navy Yard, such punishments were carried out by Boatswains Mate David Eaton in the shipyard large rigging loft. Flogging was both a form of punishment and a spectacle of intimidation. All enslaved seamen of the shipyard ordinary were forced to witness this dreadful penalty as it cutup a man’s back. The U.S. Navy did not allow flogging of enlisted men on shore station, however there were no such prohibitions protecting enslaved seamen. The U.S. Congress abolished flogging on all U.S. Navy ships in 1850.

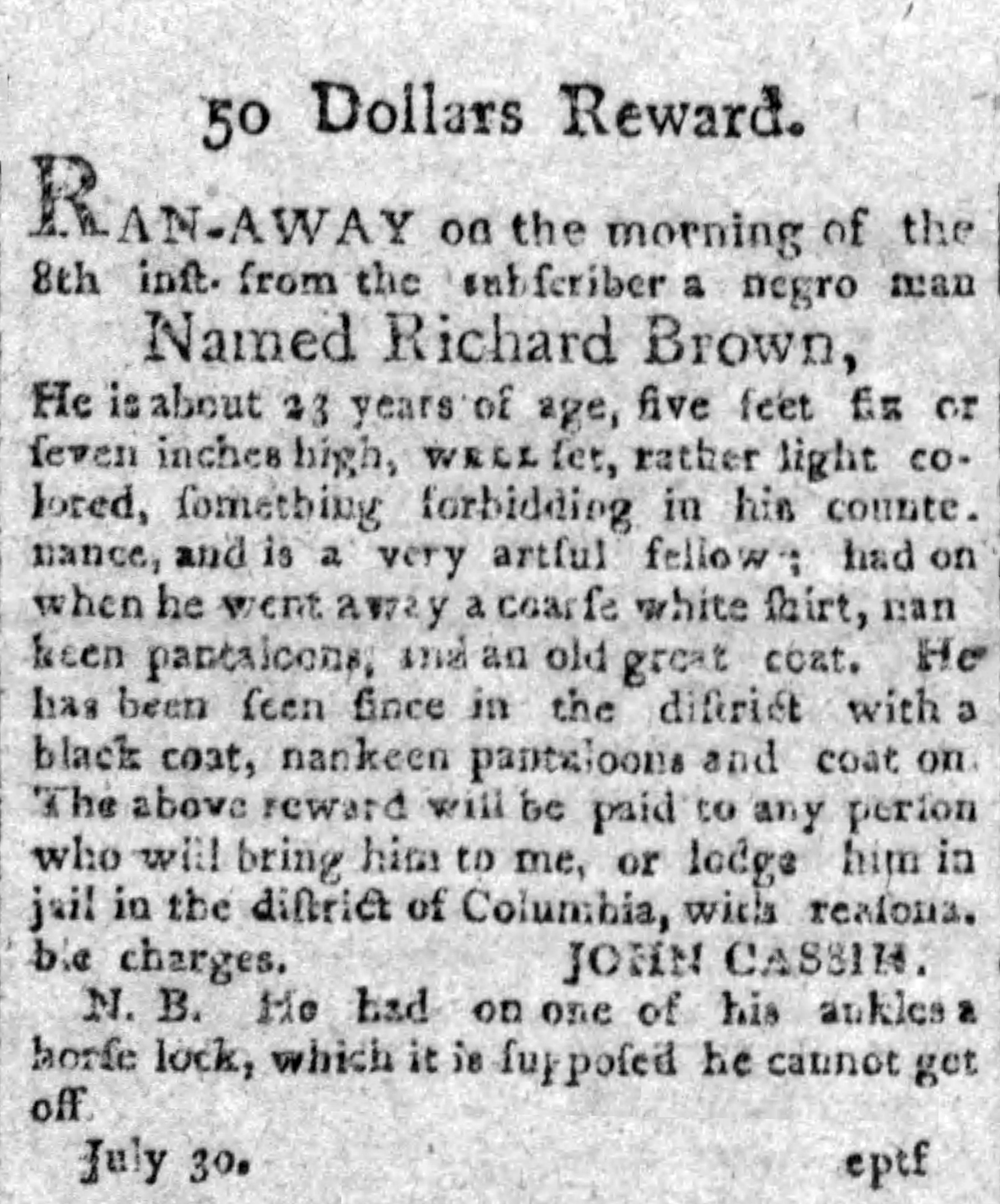

For enslaved workers such punishment was irregular and whippings infrequent, but such punishment need not be frequent to be effective and to inspire fear. Shiner also relates how seaman John Thompson, anticipating a whipping, managed to mollify the anger of the Sailing Master Barry, by "talkin quaker", that is, being publically humble and deferential to his accuser.116 Shiner himself was punished for returning late and being drunk by being placed in double irons, hand and foot, and then placed in the guard house for twenty-four hours.117 In July 1807 the indomitable Richard Brown, an enslaved Navy Yard laborer, made a daring and successful bid for freedom. While the exact circumstances are unclear, Captain John Cassin had both hobbled and chained Brown’s feet for a previous attempt, yet the ever resourceful and determined laborer escaped his confinement. Cassin, offering fifty dollar reward for the “very artful” freedom seeker’s return, complained, “He had on one of his ankles a horse lock… which it is supposed he cannot get off.

116 McKee, p. 265, quoting Richard Sutch, The Treatment Received by American Slaves: A Critical Review of the Evidence Presented in "Time on the Cross". Explorations in Economic History 12 (1975), p. 342. And Thomas Weiss review http://eh.net/node/2749 accessed by the author 2 January 2010 of Robert William Fogel and Stanley L. Engerman, Time on the Cross: The Economics of American Negro Slavery. Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1974.

117 Shiner Diary, p. 31.

For all blacks the greatest threat a slaveholder could utter was to "sell them South," which meant the breakup of their families, their friendships and their hopes and to be sent to a life of brutal plantation labor.118

118 Rockman, p. 61.

Over time the Navy became increasingly concerned with security and keeping track of enslaved "servants" became a regular function of the Yard guard force. The following extract from navy yard regulations provide some idea of this surveillance:

Officers' Servants are to be passed in and out by the Watchman at the Flagstaff; and each Servant is to be furnished (and none passed out without it) with a permit by his Master, or a pass, which in going out he is to leave with the Watchmen Aforesaid, to be returned by him next morning, or by his relief to the Officer whose name is on it. -- The Servant is not to take it with him out of the yard-- neither is it to be given back to him when he returns-- it is to be kept by the Watchman. The passes to be written on a piece of paper, & that pasted to a small board, which the Watchman can hang up in his box.119

119 Regulations of the Navy Yard Washington." Regulation number 34, http://www.history.navy.mil/library/online/wny1850rules.htm

NARA RG 45, entry 594, 1 vol., DON, Naval History and Heritage Command, retrieved 7 September 2010.The continuing use of blacks, free and enslaved, as drivers of private carriages and as servants in officers’ quarters remained a subject of concern into the 1850’s.120

120 "Regulations of the Navy Yard Washington." Regulation Number 62.

The daily station logs reveal watch officers were on occasion directed to keep an eye out for a particular slave's movements. From entry on 18 May 1828, "This day fresh breezes from the N.W. and fair weather Teppit has not made his appearance" This entry is most likely for Thomas Teppit, an enslaved man placed on the muster rolls as seaman from September 19, 1827. From the mention it is probable Teppit over stayed his pass or ran for freedom. There are two comparable entries for diarist Michael Shiner. For Saturday, 27 December 1828, the officer of the watch recorded, "Michl Shiner who had liberty out from Wednesday in till Friday morning has not came in yet" On Sunday, 28 December 1828: Shiner returned, "This day pleasant airs from the SW and fair weather. Michael Shiner got home this evening."121

121 Station Log entries 18 May, December 27 and 28, 1828, RG 181. 3.14 NARA. Thomas Teppit previously was entered on the muster rolls as an ordinary seamen, September 19, 1827 and discharged 17 May 1828, see Muster Book of the U.S. Navy in Ordinary at the Navy Yard, Washington City, from 1 January to 31. December 1828, NARA RG 45, Entry, T829, Miscellaneous Records of the Office of the Navy Records and Library, Microfilm Roll 163: Washington Navy Yard p. 51-52.

How pervasive this type of day-to-day scrutiny was is difficult to ascertain; Shiner and Teppit are the only other names mentioned in surviving logs but the regulations quoted suggest that the actual monitoring of the activities of "servants" became a fixture of gate guard duty.

The Board of Navy Commissioners (BNC) was established on February 7, 1815, and quickly became concerned with the problems of employing and managing slave labor; on 11 May 1815 the BNC wrote Tingey a strongly worded letter expressing their concern and dismay:

It is the intention of the Board of the Navy Commissioners to reestablish the Navy Yard at this place as a building Yard only, & while stating to you this intention, it may not be improper for them to make you acquainted with their views generally with respect to the establishment. They have witnessed in many of our Navy Yards & this particular pressure in the employment of characters unsuited for the public service – maimed & unmanageable slaves for the accommodation of distressed widows & orphans & indigent families - apprentices for the accommodation of their masters – & old men & children for the benefit of their families & parents. These practices must cease – none must be employed but for the advantage of the public, & this Yard, instead of rendering the navy odious to the nation from the scenes of want & extravagance which it has too long exhibited, must serve as a model on which to perfect a general system of economy. In making to you, Sir, these remarks, the Navy Commissioners are aware that you have with themselves long witnessed the evils of which they complain, & which every countenance will be given to assist you in remedying them, they calculate with confidence on a disposition on your part to forward the public interests.122

122 BNC to Tingey 11 May 1815 NARA RG E307 v. 1.

Individuals, desperate to flee a lifetime of servitude, were willing to chance everything and try for freedom despite the many dangers and obstacles. Each year hundreds of slaves within the District ran away.

Resistance to slavery took many forms and daily newspapers carried multiple advertisements placed by slaveholders for runaways. These announcements make clear the vast majority of runaways were young single men, for married men and young women running was much more difficult because of family ties and children. Some daring souls headed north but many were disappointed, for while slavery had been abolished or restricted in many northern states, simply reaching New York or Boston did not guarantee blacks safety from slaveholders or their agents, as this 1819 account of the capture and return of one of Commodore Tingey’s slave workers makes plain:

The Affray, accounts of which have been variously given in different papers in town – originated we have learned in the following manner: A slave belonging to Com. Tingey has been secured by his agent under the United States Laws, applicable to runaways: but an opportunity occurring, the black was arrested for some debt, real or nominal, and imprisoned. The debt, however, being soon discharged the slave ought in the common course of the proceeding to have been released; but we hear, the agent of Com. T. had applied to one of the Judges of the Superior Court for a writ of Habeas Corpus – the question upon which had not been determined. On Monday evening, six or eight negroes and colored persons armed with clubs and bludgeons - were observed lurking in the vicinity of the jail. And on some further indications of evil intention being exhibited, two of them were secured in prison by the watch. They had probably assembled for the purpose of taking the slave under their protection when he should be discharged to prevent his falling into the hands of his master’s agent.

On Tuesday night about half past ten o’clock, a larger body of negroes consisting of 20 or 30 armed in the same manner were observed to be collected in Court Street. Information being conveyed to the watch – one of whom asking their business, was surrounded at a signal of a whistle by 20 or more colored people. He was answered in a very imprudent manner, and presently afterwards one of the watchmen was knocked down with a club by a black fellow who approached him for that purpose. Immediately an alarm was given, and after great tumult and noise, about 15 blacks were secured, who next morning were examined before Mr. Justice Gorham on the charge of an assault; and four of them were bound over to take their trial at Municipal Court on the Monday next.123123 Commercial Advertiser 4 January 1820.

For most slaveholders, the flight of their bondsmen to the North was greatly to be feared, for retrieval was difficult and slave catchers expensive; Tingey, however, was not dissuaded.

The majority of escapees tried to settle in and pass as manumitted or free among the large black populations of the District and Baltimore. The exact number of runaways is difficult to ascertain and the documentary record often absent. Many runaways simply wanted time away from their master, to visit a spouse, family, or friends, and returned voluntarily while many other runaways were quickly recaptured and returned. Occasionally we can gather glimpses of such runaways. One such was Davy Gardner. In separate depositions, Thomas Talburt and George Barnes, both white navy yard employees, recounted how they recaptured young Davy and returned him to master mechanic, Peter Gardner.124 Gardner died 3 June 1811 and the inventory of his estate, enumerated Davy Gardner as sold for $190.125

124 Peter Gardner to Tingey 29 June 1808 and attached affidavits of Talburt and Barnes both 28 June 1808 NARA RG45/M125. Thomas Talbert, shipwright apprentice, gave evidence at the inquiry into the conduct of master mast maker, Peter Gardner. Talburt described how he with fellow worker George Barnes had retaken slave apprentice mast maker David "Davey" Gardner back to his master Peter Gardner, " I Thomas Talbert make Oath on the Evangels & Almighty God that at night about the latter part of last summer I took up a negro man Slave belonging to Peter Gardner & I carried him home - he were supposed to Runaway ….."

125 NARA RG 21 Records of the District Courts of the United States, Entry 115, O.S. Case File 448 Peter Gardner 28 June 1811.

As historian Peter H. Wood stressed, "No single act of self-assertion was more significant among slaves or more disconcerting among [southern] whites than that of running away."126 Slaves were valuable property and slaveholders frequently went to great lengths to recover fugitives, including offering rewards for capture and return. Master painter Patrick Kain offered 12½ cents for his young apprentice Jesse Cross, whereas in contrast, slaves had large bounties placed on them.

126 Harrold, Stanley, Border War: Fighting Over Slavery Before the Civil War, Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2010, p. 39, quoting Peter Wood, Black Majority: Negroes in South Carolina from 1670 through the Stono Rebellion, New York: Knopf, 1974, p. 158-159.

Runaways with marketable talents such as blacksmiths and ship caulkers were valuable, hence slaveholders were often desperate to reclaim their lucrative possessions.127 One such runaway was David "Davy" Davis, born in Upper Marlboro, Prince Georges County, Maryland, circa 1785, on the Mount Airy estate of wealthy planter Edward Henry Calvert (1766-1846). Calvert, a slaveholder with over fifty bondsmen, including Davis, began life with a vast amount of real estate, but after years of financial distress, he eventually owed his brother, George Calvert $20,000 dollars by 1810.128 His sister-in-law Rosalie Stier Calvert wrote Edward was an "honest man", a poor manager and "in despair." To pay, Edward sold large portions of his inheritance and holdings. Included in this sale were numerous enslaved individuals among them David Davis. Nothing in the surviving documents provides even a glimpse of Davis' early life, although David probably learned the blacksmith trade at Mount Airy. About 1808 Calvert sold Davis to James Cassin (1778-1828). Cassin, an immigrant from Ireland, worked as an auditor clerk at the Navy Department.129 As a naval auditor Cassin had extensive day to day connections with naval officers and used them to rent Davis, per diem, as a blacksmith to the Navy Yard. Cassin had five other enslaved individuals in his Georgetown household.130

127 Franklin, John Hope and Schweninger, Loren, p.,209 -33.

128 Mistress of Riversdale: The Plantation Letters of Rosalie Stier Calvert (1795-1821),edited by Margaret Law Callcott, The Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, 1991, p. 229.

129 James L. Cassin memorial

http://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=gr&GRid=59647401130 1820 US Census for the District of Columbia Georgetown.

As a blacksmith striker at the Navy Yard, Davis worked six days a week, twelve hours as day. He worked in a large shop composed of 47 journeymen, apprentices, laborers and slaves. His overall supervisor was Master Blacksmith Benjamin King. The blacksmith shop where he worked made extensive use of enslaved labor. King owned five slaves and with other senior officers and civilians such as Commodore Tingey, Master Plumber John Davis of Abel, Master Mast Maker Peter Gardner and Clerk of the Yard Thomas Howard made handsome profits leasing their slaves to the Navy Yard.

Slavery was profitable both for the slave owners who pocketed the enslaved workers wage and for the Navy Yard since white blacksmiths were paid $1.81 per diem versus 80 cents per day for each enslaved worker.131 Most of these enslaved men, like Davis, were used for heavy work as strikers, wielding large hammers to beat molten metal into anchors.132 The payroll for 1811 reflects as many as 19 slaves, including the 5 owned by King himself.

131 Warden, 64.

132 PAY ROLL for Blacksmiths, employed in the Navy-Yard, Washington in the month of July 1811, accessed at: http://www.genealogytrails.com/washdc/wny1811.html.

Davis with Jim, another of Cassin’s slaves, sought freedom and escaped on 14 June 1809. A reward notice ran on 16 June 1809 proclaiming a $100.00 reward for Davis and Jim.133 In addition to the reward notice in newspapers, Cassin had reward posters printed up and circulated within the District and in Prince George County. This 1809 poster is a rare surviving example of what once was a common sight in the District of Columbia.

133 National Intelligencer 16 June 1809.

ONE HUNDRED DOLLARS REWARD

FOR apprehending the following NEGRO MEN, the property of the subscriber, residing at Washington City and who ran away on the night of the 14th inst.

DAVID is of dark color, about 25 years of age, and has lost a joint of one finger of his right hand.

The other by the name of JIM, about 35 years of age, also a stout male, has been sickly and is jet black. David was bought of Major Calvert, Mount Airy, and is expected will be about there. Jim was bought of Mr. Samuel G. Griffin, of Baltimore, and will no doubt make for that city. They are both old runaways, and will try to pass for freeman. The above reward will be given for both or half the sum for either, with reasonable charges.June 16 - JAMES CASSIN

Cassin labeled the two men "old runaways" implying they had made previous attempts to find freedom. He also stated they "will try to pass for freeman" perhaps presenting forged freedom papers with the implication that one or both may have been literate.

By 17 June 1809 Davis was captured and held in the District of Columbia Jail. Somehow Davis was able get an attorney to file a petition on his behalf in the District of Columbia Circuit Court stating that he was illegally held in bondage and that James Cassin sought to remove him from the District and take him to the lucrative slave market of New Orleans for sale.

The humble Petition of Davy Davis, humbly sheweth, that your Petitioner is detained in slavery by James Cassin — and as he is born free he prays that process may be awarded to compel the appearance of the said James Cassin to answer his complaint.

Your petitioner begs leave to state that the said James Cassin is about to remove him from the District of Columbia & to take him to New Orleans, for the purpose of there selling of him, that he has already confined your petitioner in irons for that purpose, your petitioner therefore prays that process immediately be issued to bring the said James Cassin before the court for the purpose of compelling him not to remove your petitioner out of the district & to permit him to appear & assert in court his right to his freedom as in Duty bound he will ever pray—The District Marshall directed

You are hereby commanded to Summon James Cassin if he shall be found within the County of Washington that all excuses and delays set aside, he be and appear before the Court here immediately, to answer the Petition of Davy Davis in this Court filed against him for his freedom. Hereof fail not at your peril and have you then & there this Writ. Witnessed by the Hon. Wm. Cranch, Chief Judge of our said Court, the 17th day of June 1809.134

134 Davy Davis vs. James Cassin Petition for Freedom

http://spacely.unl.edu/cocoon/dccourts_test/doc/cases.davis.davy.pet.htmlDavis suit was of no avail. Cassin reclaimed him and again rented him to the Navy Yard. The July 1811 payroll reflects David Davis employed that month for 18¼ days @ 85 cents per day. James Cassin, slaveholder, signed for and collected Davis' monthly pay of $15.54.135

135 July 1811 Payroll Washington Navy Yard http://genealogytrails.com/washdc/WNY/1811payroll.html

"Black Men in preference to white & of them Slaves before Freemen"

In 1803 the average wage for the District was reported as $0.75 cents.136 In 1816, a visitor to the shipyard wrote, that master blacksmith Benjamin King estimated the daily expense for a slave at twenty seven cents and noted how lucrative the business was. The Navy was paying eighty cents per day for black workers while white blacksmiths were paid $1.81 per diem. King stressed: "The masters or proprietors of stout black laborers hire them at the rate of sixty dollars a year. Their food and clothing are estimated at thirty-five dollars."137 Not surprisingly, King strongly rationalized and endorsed the continuance of slave labor. Writing in 1809 to Commodore Thomas Tingey, King made the case for enslaved labor explicitly: "Experience has pointed out the utility of employing Strikers Black Men in preference to white & of them Slaves before Freemen – The Strict distinction necessary to be kept up in the shop is more easily enforced – The liberty the men take of going & coming is avoided, the Master of slaves for their own interests keep them to work. The Habits of Labor they are Inured to & their ability to stay at it are strikingly Obvious – It also takes some time to learn their Business & the time a White Man learns, he quits & the trouble is to be renewed – "King to Cassin, January 14,1809, RG45/M125, NARA.

136 Brown, p. 130.

137 Warden,,D. B. A Chorographical and Statistical Description of the District of Columbia, the Seat of the Government of the United States. Paris: Smith and Co., 1816, p. 46 and 64.

Davis was determined to escape enslavement and make a life for himself and in 1812 he made another flight to freedom that was apparently successful.

30 Dollars Reward

Spirit of 76 Georgetown DC 11 August 1812RANAWAY from the subscriber on the evening of the 19th, a NEGRO MAN by the name of DAVID DAVIS – He has worked for four years past in the Navy Yard, in the Blacksmith Shop- is well known about there- He is about 25 years of age, 5 feet 10, or 5 Feet 11 inches high – He has some time since his left arm broken, and has lost part of his forefinger. He formerly belonged to Edward H. Calvert in Prince Georges County, where he has friends – He has a wife at the Navy Yard – and has been in Baltimore Jail twice. I will give the above reward if lodged in any Jail so that I get him again, and reasonable expenses if brought to

THOMAS QUANTRILLThe Editors of the Baltimore Whig and Philadelphia Aurora will insert the above three times and forward their accounts to the subscriber.

The determined Davis made two attempts, the second apparently successful:

Daily National Intelligencer 2 June 1812, "Thirty Dollars Reward, Ran away from the Navy Yard on Monday the 28th of May, a Negro man the property of the subscriber, known by the name of DAVID DAVIS; he has been working for the last three years as a helper in the blacksmith’s shop; he is about 25 years of age, and 5 feet 10 to 5 feet 11 inches height; some time ago he had his left arm broken, and lost his fore finger. I will give $20 for the apprehending him if taken in the district, or 30 if out of it and lodging him in jail. He was bought of Ed. H. Calvert in Prince George’s county, where he has some friends, and it is probable he will stay about there; he has been in Baltimore jail where I bought him out. All persons are forbid harboring him under a penalty.

J. Cassin

P. S. Should he voluntarily return to his master, he promises to forgive him."138138 Daily National Intelligencer, 2 June 1812.

Cassin’s appeal "Should he voluntarily return to his master he promises to forgive him" is a common plea in District reward notices of desperate masters hoping to cajole a runaway slave into voluntarily return.

District slaveholders were often uncertain regarding their chattel's appearance. The notice below for Nathan Brown, AKA "Terry" or "Jerry", demonstrates such confusion even over the basic facts. Confused as to the runaway’s name, John Davis of Abel published two separate notices to catch his young blacksmith bound for the new Republic of Haiti. For all fugitives having a pass signed by slaveholder or certificate of freedom was essential, indeed Brown may have been literate. Slaveholders like Davis often catalogued the fugitives' alibis with a sense of outrage and grievance that their bondsmen had chosen a name and could write.139

139 Waldstreicher, David Runaway America Benjamin Franklin Slavery and the American Revolution Hill and Wang: New York, 2004, p.11.

Daily National Intelligencer 2 March 1825 "Thirty Dollars Reward Ran Away from the subscriber, on the night of the 19th of February, a Negro Man named Terry (but who calls himself Nathan Brown) about 21 or 22 years of age, about 5 feet, 5 or 6 inches high, of rather a red cast of complexion, with a wide mouth and thick lips; a scar over one eye by a burn, tolerable bushy head. He is a tolerable smith and has worked much at the Anchor Smith business in the Navy Yard. He is artful and plausible in his discourse. I have little doubt that he procured forged papers, as a man answering his description took passage for Baltimore, and having papers signed by two persons, one Trueman Tyler Clerk of Prince Georges County, he will make for Haiti by first chance. He professes to belong to the African Bethel Methodists. He has a variety of clothes so that his dress cannot be well described; they are however generally good and he is fond of being well dressed. Ten dollars reward will be given if taken in the District, and thirty if taken elsewhere, and all reasonable charges paid. JOHN DAVIS of Abel.

Slaveholders were frequently loath to admit their "servants" aspirations and often used what one scholar has referred to as "a rhetoric of pretense" disparaging the fugitive while conveying information.140 The notice below posted on 30 April 1817 is an example. Anna, a young woman, was making toward the District with Nat Cummins who had worked at the Yard:

RANAWAY from the subscriber, on Sunday afternoon, the 13th inst a negro woman named ANNA, about 22 or 23 years old, 5 feet 6 or 7 inches high, light complexion, speaks quick and confusedly when questioned closely - stout made, fat, appears to be advanced in pregnancy, and is remarkably lazy. Had on when she went away a cross-barred home-spun frock, cross-barred handkerchief on her head and a white one on her neck- besides which she conveyed some weeks ago a variety of clothing, among them a black silk and one or two white cambric frocks. Her wool, which is very long and plaited, she generally wears nicely combed. She was purchased about nineteen months ago, from Joseph N. Stonestreet near Piacataqua, Md., a few miles below which she has a grandmother who is free. It is supposed that she is accompanied by a yellow man who calls himself Nat. Cummins, who formerly lived with Captain Haraden, in the Navy Yard and a few weeks with Capt. James Cassin in Georgetown. He is about 5 feet 10 or 11 inches high, slender male; had on when seen last the habit of a sailor. Whoever will take up and secure said women so that I get her again, shall receive a reward of ten dollars if in the District, or if taken out of the District, the above reward of twenty dollars will be given, and all reasonable expenses, if brought home.

April 15 - JOHN D. BARCLAY141140 Waldstreicher, p.9.

141 Daily National Intelligencer, 30 April 1817.

The shipyard was a logical place for fugitives to meet fellow blacks and sympathetic whites to look for assistance and help to secure passage north.

Slaveholders often expressed concern in their notices that "servants" were endeavoring to reach the Navy Yard where they might find help and assistance from family members, friends or a sympathetic ship captain or crew member to help them gain freedom.

John G. Reese, a Georgetown slaveholder, wrote that his "Negro man named Gusty Hall had brothers living at the Navy Yard."142 Henry Hawkins likewise was said to have had a mother living at the Navy Yard. Isaac Beall too posted notice that his man Charles, a rough carpenter, might be bound for the Navy Yard where he had an uncle named Adam, and John Bast warned readers his man Tom Cooper had already been seen at the Washington Navy Yard. 143142 Daily National Intelligencer, 1 July 1842.

143 Daily National Intelligencer, 20 April 1813 and 12 January 1831.

Thomas Smallwood (1801-1883) one of the most remarkable opponents of slavery was born in Prince George County, Maryland. Slaveholder John B. Ferguson taught Smallwood to read and write and agreed to free him at age 30 for $500, which he paid in installments. Smallwood developed a fondness for British literature and particularly the works of Charles Dickens. Smallwood often used the nom de guerre "Samivel Weller, Jr.," after one of Dickens memorable characters.144 Known as "Smallwood of the Yard" he first worked as a shoemaker and opened a shop near the Navy Yard gate. In the late 1830’s he became interested in African colonization. After the collapse of the colonization movement, he became an ardent abolitionist working for the Underground Railroad. Beginning in the 1840’s Smallwood operated a station together with his wife Elizabeth, the white Reverend Charles T. Torrey and a white landlady, Mrs. Francis Padgett. Their brave group assisted over one hundred people in the District to flee slavery.145 One of their more daring schemes was to help the slaves of Secretary of the Navy George Edmund Badger in their bid for freedom.146

144 Smallwood, p. 63.

145 New York Tribune, August 26, [1850] and Pennsylvania Freeman, 5 September 1850 email Stanley Harrold to author 2 September 2010.

146 Smallwood, p. 18-20. George E. Badger, Secretary of the Navy, 6 March 1841 - 11 September 1841.

Smallwood would later explain his commitment to such radical activism thus:

But they should also remember that justice has two sides, or in other words, a black side as well as a white side. And if it is just for slaveholders to compel men and women to work for them without pay, because they are black, and they have the power to do so; then it is equally just for them, or their friends to deprive their masters of such labor without pay.146a

146a, Scott, pp. 62 - 63.

Smallwood and Torrey’s tactics were bold: they taunted, goaded and belittled slaveholders by writing letters both to the editor of local papers and to individual slaveholders. In a letter to the Albany Patriot, Smallwood took credit for aiding some "of the NATION’S SLAVES in escaping from the NATIONAL PRISON, to wit this city of Slave Pens and Slave Traders."147 Taking increasingly audacious risks and waging what scholar Stanley Harrold has referred to "as a form of psychological war," Smallwood and Torrey threatened slaveholders, police informers and constables with death.148 Torrey was arrested in 1844 and died in prison. Smallwood’s activities gained him unwanted notoriety and he came to the notice of the District’s Auxiliary Guard leader, Captain John H. Goddard.

147 Albany Weekly Patriot 8 December 1842.

148 Harrold, Border War, p. 123-124.

For African Americans, encounters with the District police force and the Auxiliary Guard were rarely pleasant. Each evening the District’s ten o’clock bell was the signal for all blacks, free or slave, to be off the streets unless they had a special pass. The punishment for any infraction of this curfew was arrest, fine and/or flogging with "ten lashes well laid on." The District of Columbia whipping post was located in the Guard House and sometime whippings were administered in the jail near the North East corner of Judiciary Square. Those blacks resisting the Guard were subjected up to 39 lashes.149 Everywhere in America laws protecting slaveholder’s property and their right to reclaim their bondsman prevailed. As in many cities, a duty and responsibility of law enforcement was to help recapture runaway slaves. Consequently, the Auxiliary Guard spent considerable time assisting slaveholders track and recapture their escaped slaves. They were moreover responsible for the apprehension of any person, black or white, assisting flight. Smallwood described the Guard’s surveillance of his network:

My house was surrounded early on the night proceeding the morning I was to start with my family, by the watch and Goddard, their Captain, at their head. I was seated in the front door when a policeman with whom I was acquainted came to me and said, "Thomas I have been instructed in consequence of information that you intend starting for Canada with some slaves and have come to search your house. I invited him to do so, afterwhich he left the inside of the house but did not leave the premises until searching the house a second and third time, the last of which the blackguard Goddard came in and said, "Smallwood, I understand you are going off to Canada and intend to take slaves with you." He then proceeded to examine those in the house as to whether they were chattels or free negroes. There were ten or twelve persons present in the house at the time, preparing to leave for Canada the next morning and take a final leave of such beautiful scenes of republican freedom. It is true that I had another slave woman concealed in my house and for whom I had been trying to make a way of escape, but I had no intention of taking this woman or any other slaves with me for I had made arrangements with confidential friends to take and keep her until a way of escape could be made. But to get her out of the house unperceived was a matter of great importance. However, that was speedily accomplished by some females who took her through a back door into the garden, and concealed her in some corn.150

149 Baltimore Sun 7 November 1842, for an account of the whipping of "Sam" for resisting an Auxiliary Guard "in the performance of their duty."

150 Smallwood, p.33.

Free people of color like Smallwood had no protection from the Guard. Smallwood finally gave up his perilous activities after his attempt to aid fourteen persons to flee was discovered, causing him to abandon his charges with the police in hot pursuit. After this disastrous attempt, Smallwood went to Toronto, Canada, where he lived the remainder of his life as a free man.151

151 My description of Thomas Smallwood and his activities at the Yard and in Washington D.C., is drawn largely from Stantley Harrold’s Subversives Antislavery Community in Washington, D.C., 1828-1865, Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University, 2003 p. 64-93.

The example set by Smallwood of acting boldly and taking the initiative continued on at the Yard. Blacksmith strikers Daniel Bell and Anthony Blow, after years of hard work to gain their freedom, were determined to gain liberty for themselves, their families and friends. Bell’s wife and children were the property of another slaveholder, Robert Armistead, master ship caulker. On 14 September 1835, shortly before Armistead’s death, Daniel Bell persuaded Armistead to manumit his wife Mary and six of his children.152 Bell’s wife Mary was to be freed at Armistead’s death, while each of the Bell children were to be set free only after serving various stipulations of limited term servitude, e.g., Andrew Bell, sixteen in 1835, was to be set free at age forty. Following Armistead’s death, his widow, Susannah, began to take legal action to set aside the manumissions.153 Susannah complained to the District Court that her late husband was ill and lacked sufficient mental competency to make such important financial decisions. Daniel and Mary Bell, with the help of a few sympathetic whites, brought actions to challenge Susannah Armistead. Mrs. Armistead, however, ultimately prevailed and the District Court awarded her full title to the Bell children as "slaves for life." Susannah Armistead, in need of money for her own large family, began to make plans to sell the Bell children to slave dealers. Daniel Bell’s wages of slightly over $30.00 per month were simply insufficient to ever purchase freedom for his wife and children.

152 NARA RG 21, Manumission and Emancipation Records, volume 2, p.404 -405.

153 NARA RG 21, Entry 115, O.S. Case file, 1832, Robert Armistead. "Inventory of slaves and other property belonging to the estate of Robert Armistead Susannah Armistead, Administrator, 1838."

The Bells, desperate to save their family from being broken up and their children sold South, became primary organizers of the largest attempted mass slave escape.154 Daniel Bell joined enslaved blacksmith striker Anthony Blow and freemen Paul Edmonson and Paul Jennings in purchasing the aid of Captain Daniel Drayton of the Schooner Pearl to help their families and other acquaintances flee north. In all seventy-six men, women and children attempted this perilous journey north. Tragically, their daring plot was quickly foiled and all those aboard the Pearl were apprehended, including Daniel’s wife Mary, eight of the Bell’s children, and two grandchildren. The Bells and the others were jailed. The family was later returned to Susannah Armistead as "slaves for life." Daniel Bell was able to keep his job at the navy yard, although his wage was reduced from $1.20 per day to $1.12 per day. Daniel Bell through arduous effort over time purchased the freedom of various family members, but his son Daniel Bell junior, he never saw again, for Daniel had been sold south.155

154 Harrold, Subversives p.119. Harrold speculates that Daniel Bell may have known Thomas Smallwood. While there is no specific documentation, they almost certainly worked together in the 1840’s, and both were inhabitants of a small world where the number of black employees on the Yard was substantially reduced by the 1840’s.

155 ForDaniel Bell’s position as a laborer in the Blacksmith Shop and pay, see NARA, RG71, Records of the Bureau of Yards and Docks 1784-1962, Shore establishment payrolls, 1844–1899, Payroll January 1848 shows Daniel Bell, Occupation Smith, Days Worked 22 ½, Wages in total for Month $31, 20.

Slavery and Free Labor

Not surprisingly white workers' attitudes mirrored that of the general population and their surviving letters reflect a growing resentment of black employment.156 Whites and blacks toiled together, yet lived apart and rarely had other social interaction. One of the first critics was Commodore John Rodgers. In 1804 Rodgers sent Benjamin King a stinging letter complaining of the quality of work performed by the blacksmith shop with its largely enslaved workforce and referring to them as "creatures."157 Periodically public resentment against officers and civilians renting their bondsmen to the Navy came to the fore. One critic specifically complained, "Another officer hires a negro for 60 dollars per annum and lets him to a superior officer for one dollar per diem. A fine speculation, but public losses are private benefits."158 One District resident stated that the employ of slaves at the shipyard and other public installations prevents white men from accepting work amongst them as the "whites feel it to be a degradation"159 White foremen and workers expected all blacks to be deferential, but over time black workers began to speak out and to question the equity and fairness of their pay.160 In 1812 a petition to the Secretary of the Navy from a group of white blacksmiths stated their resentment of blacks they perceived as "insolent."

Your petitions further complain that they [ar]e now subjected to the insolence of negroes employed in the Navy Yard, altho’ no redress is [suffic]iently provided for your petitioners against the misconduct of blacks. That one of their body was lately threatened with being discharged for having struck a negro who had grossly misbehaved & they conceived that some provision ought to be made for the purpose of restraining the misconduct of blacks & of only employing such as are orderly & absolutely necessary.161

156 Anonymous to Levi Woodberry, 27 August 1831, RG 45/M149, NARA, re complaint blacks are employed "when very well-qualified" whites may be available.

157 John Rodgers to Benjamin King 15 June 1804 RG45/M125 NARA.

158 Spirit of Seventy Six 6 October 1810.

158 Daily National Intelligencer 26 April 1816.

160 Tingey to Hamilton, 1 August 1809, RG 45/M125, NARA.

161 Blacksmiths petition to Hamilton, circa October 1812, RG 45, NARA. Tingey in response stated his displeasure but his "understanding however that the negro who was struck had been extremely careless in his duty & gave provocation thereby ..." For the response, see Tingey to Hamilton, 7 October 1812, RG 45/M125, NARA.

Free blacks were excluded from supervisory positions and, except in a few instances, from all apprenticeships in skilled crafts such as shipwright or carpenter. White mechanics frequently expressed fear of economic competition from slave labor. One writer condemned the BNC as "Unfeeling men! You have reduced the wages of this yard. What an abominable act of tyranny!"162 A local annalist writing in 1825 expressed the same concern, "There is a general disposition to reduce the pay of laborers to a small pittance, and to introduction and employment of non-resident slaves a policy which is injurious to the interest of the city."163

162 Washington City Weekly Gazette 7 June 1817.

163 The Sessford Annals, District of Columbia Historical Society, Records, 1908, XI, 282.

After examining federal shipyard wages, Linda Maloney concurred. She noted workers' fears, while certainly misdirected, had some rational economic basis, that is, the so-called "cooling" effects of enslaved labor on free wages had a harsh reality. Maloney found laborers at the mostly all white, Massachusetts, Charlestown, Naval Yard, received wages of $1.00 a day and sometimes more while those at navy yard, both white and black, earned but $0.72 cents.164

164 For the "useful check" of slave labor on white employees, see,Thomas Johnson, David Stuart and Daniel Carroll, Commissioners to Thomas Jefferson, 5 January 1793, Commissioners Letter book Vol. I, 1791-1793, NARA RG45. For the wage difference between Charlestown and Washington DC, see Maloney p,421.

Seth Rockman in his careful study of wage labor in Baltimore found wages remained flat between 1790-1820. Rockman reveals the price of labor in Baltimore was essentially fixed at $1.00 per day, and the value of a day’s work hinged on the prices of everything else, especially food, housing and fuel. Rockman concludes by noting that real wages dropped during the first decade of the century so that workers paid $1.00 per day in 1795 found their wage worth $0.85 cents in 1809.165

165 Rockman, p. 72.

We are fortunate to possess some specific wage data.166 Responding to a BNC request in 1821, Tingey supplied data on the scale of wages for various occupations from 1801-1820 (see Appendix E). While most of the data covers the decade 1810-1820, there is sufficient evidence to reveal a significant drop in worker's income. For example, in 1801 a painter’s per diem wage was set at $1.56, in 1820 a painter's daily wage was but $1.52-1.32. Far worse were the wage rates for ship caulkers. Tingey reported they were paid $1.81 in 1810, but, their wages declined to $1.44 by 1820. Shipyard laborers, who occupied the lowest rung in the hierarchy, were paid $0.85-0.75 cents in 1810 and a decade later saw their wages declining to $0.80-0.68 cents in 1820. Ship caulkers and laborers, two occupations with large numbers of blacks, saw considerable decline. Competition from slaves was not the determinative factor in the flatness of wages in Washington. Wages were low because there was a surplus of low-end white workers and those workers had little political leverage in the District or elsewhere because craft workers saw them as competitors rather than allies and thus excluded them from their organizations.

166 Tingey to BNC 9 January 1821, see Appendix C.

One master mechanic saw yet another benefit in employing slave labor when he noted that the navy yard could count on local slave owners to supply the necessary labor and help enforce discipline: "The Strict distinction necessary to be kept up in the shop is more easily enforced – The Liberty white men take of going & coming is avoided, the Master of Slaves for their own interest keep them at work."167 The Secretary of the Navy and BNC were certainly aware white workers feared black competition. One letter to the Daily National Intelligencer following the War of 1812 stated the workers' fears. The writer complained that white workers came into the District in answer to advertisements for skilled labor, but left once they found wages low and blacks in such number that they returned "disgusted as they would not associate with the negro slaves who are poorly fed and clothed and who are unfit companions for free whites." The writer warned: "Can the God of justice behold this metropolis of a republican nation filled with poor slaves and not condemn such a deviation from the principles of the constitution and equity?" The correspondent’s proposed solution was that the "government should pass a law against the employ of slaves on public works."168 The main concern appears to have been the number of officers and master mechanics who rented their slaves to the Navy. The Board occasionally took drastic steps to limit the number of blacks, and on 17 March 1817 they issued a circular to all naval shipyards banning employment of all blacks and, apparently, questioning the activities of some whites:

Abuses having existed in some of the Navy yards by the introduction of improper Characters for improper purposes, the Board of Navy Commissioners have deemed it necessary to direct that no Slaves or Negroes, except under extraordinary Circumstances, shall be employed in any navy yard in the United States, & in no case without the authority from the Board of Navy Commissioners.

167 King to Stephen Cassin, 14 January 1809, RG 45/M125, NARA.

168 Daily National Intelligencer 26 April 1816.

The same day BNC President Commodore John Rodgers sent a letter to Tingey reminding him only white employees were to be employed to replace the now banished black employees.

All Slaves & Blacks are to be discharged from the Navy Yard & none are to be employed in future, except under extraordinary Circumstances - & even then, they are not to be so employed except by the authority of the Navy Commissioners. Efficient white mechanics & Laborers are to employed to supply the places of those discharged under this order.

Characteristically such orders restricting black employment were followed quickly by a period of waivers and exceptions as officers, senior civilian employees and slaveholders lobbied and pressed the Secretary and the Board to make accommodation for slave labor.169 Tingey in fact quickly replied:

I have discharged all slaves and blacks agreeable to your order of the 17th Inst, fourteen of which were employed in the anchor shop. Mr. Davis, Master Blacksmith, has made a report to me that the shop cannot be carried on without such men as have been discharged which cannot be obtained …

169 BNC Circular to Commandants of Naval Shipyards, 17 March 1817, RG 45, NARA, "Abuses having existed in some of the navy yards by the introduction of improper Characters for improper purposes, the Board of Navy Commissioners have deemed it necessary to direct That no Slaves or Negroes, except under extraordinary Circumstances, shall be employed in any navy yard in the United States, & in no case without the authority from the Board of Navy Commissioners."

One District resident complained of "the capricious despotism of discharging the black laborers from the navy yard of this city to make room for whites who have been found wholly inadequate to the performance of their duty, and to assist where it has been necessary to employ blacks without whose aid the work could not be accomplished."170 Perhaps, in response to such criticism, Commodore Tingey took out advertisements to attract white blacksmiths, offering them "constant employment and liberal wages." Likewise the Board increased white wages:171

The Board of Navy Commissioners, understanding that a difficulty exists in getting good white strikers for the yard at the present wages, have agreed that for strikers of that description there may be allowed $1.37 per day & you are accordingly authorized to allow that sum.

170 Essex Patriot , 7 June 1817, quoting the City of Washington Gazette.

171 City of Washington Gazette, 15 May 1818.

The Commodore and the Board’s efforts were to no avail. The number of blacks on the rolls declined with all the periodic banns and dismissals, yet few whites wanted to work as blacksmiths. Writing to the Board on 16 August 1821, Tingey stressed his belief, "no doubt that the number of blacks in Mr. King’s shop has been somewhat augmented" and expressed his frustrations:

The number of blacks working under Mr. King [Master Blacksmith] at the present is seven – I propose discharging the whole of them on Saturday evening next – which will afford opportunity to learn whether white men can be obtained to supply their places – if not, the inconvenience will be but temporary as the blacks, I predict, can be readily procured again if necessary.172

172 Tingey to BNC 16 August 1821.

The Navy discovered white men did not come forward to fill vacancies, even for higher wages for jobs in the Blacksmith Shop, and consequently they approved three free and two slaves as blacksmith strikers, albeit temporarily. Still complaints from white employees continued to plague Tingey and the BNC. On 15 July 1823 Tingey again assured the Board that he was trying to reduce reliance on black labor and emphasized that his Clerk of the Yard, Thomas Howard, "has not owned a male slave for several years. Those black men are all again discharged."173 Despite the avowed intention to reduce slave labor, many in the leadership cadre continued to encourage and justify slave and free black labor as absolutely essential to production in the Anchor shop and wherever work was difficult, dangerous or dirty.174 The following rationalization from 1830 is typical:

The competent mechanics have long known them [slaves] and I have no cause to complain. On the contrary I consider them the hardest working men in the yard, and as they understand their work they can do much more work in a day than new hands could, and I should suppose it would require many weeks if not months to get a gang of hands for the Anchor Shop to do the work that is now done.

173 Tingey to BNC 15 July 1823.

174 Cassin to Smith 10 May 1808, RG45/M125 NARA, "Understanding it is the intention of the Secretary of the Navy to discharge all Slaves employed in this Yard, I Beg leave to observe there are but very few white men in this neighborhood that can be found to fill their places even for one fourth higher wages."

The African American Workforce 1830.

On 8 April 1830 Commandant Isaac Hull forwarded to the BNC a list of 214 civilian employees showing the number of black employees was greatly reduced from its 1808 high point. In 1830 this number included 13 enslaved and three free workers, approximately 7 % of the workforce. Two of the free blacks, John Thompson and Nat Summerville, and six enslaved were assigned to the Blacksmith Shop where all worked as blacksmith strikers. George Carnes, a black freeman, worked on the latest technological marvel, a steam engine, used to power much of the machinery and mills. The remaining seven workers, including Michael Shiner, were employed in the ordinary. The BNC had requested the name, occupation, wage or salary of each employee. On 8 April 1830 (see Appendix C), Commandant Hull sent a follow-up letter to the Commodore John Rodger, President of the BNC, providing him a list of all blacks, free and slave workers:

I have understood from Captain Shubrick that when you were last in the Navy Yard you enquired of him whether Slaves belonging to Officers were employed at the Yard and at the same time informed him there was a positive order against employing Slaves belonging to Officers. I have caused a search to be made but cannot find any such order either by circular or by letter receipted for this yard and I have found all the Slaves now in the yard and many others that I discharged since I took the Command here, I took it for granted they were employed by Special Permission and that permission given because while men could not be found to work in the Anchor Shop. I now have the honor to forward a list of all the Slaves now employed in the Yard. Those belonging to the ordinary might be discharged and White Men or free Blacks taken to fill their places but I fear we could not find a set of men White or Black or men even Slaves belonging to poor people outside the yard to do the work the men now do in the Anchor Shops. The competent mechanics have long known them and I have no cause to complain, on the contrary, I consider them the hardest working men in the yard and as they understand their work they can do much more work in a day than new hands could and I should suppose it would require many weeks if not months to get a gang of hands for the Anchor Shop to do the work that is now done.175

175 Hull, to BNC 5 April 1830.

Rodgers' request was prompted by letters of complaint received in January 1830 from a large group of white stonemasons at the Gosport Navy Yard. The Gosport workers protested the hiring of slave labor especially as skilled workers. Rodgers took their complaint seriously and pressed Hull for detailed information.176 Hull found, to his apparent surprise, four of his senior civilians, master mechanics John Davis of Abel and James Tucker and Clerk of the Yard, Thomas Howard, and Inspector of Timber, James Carberry, plus three of his own officers, Lieutenant George D Ramsay, Naval Storekeeper, Cary Selden and Naval Purser George Beal were collecting the wages of their slaves rented to the navy yard.

176 Tomlins, p. 498.

The one significant group of African Americans employed on the Yard that we know little about is the "domestic servants." These men, women and children do not appear on any of the civilian musters or payrolls. These individuals, both enslaved and free, worked as domestics for the Commandant and other naval officers. The domestic workers lived in and near what is today Quarters A, originally Commodore Tingey's house, and Quarters B, Lieutenant Nathaniel Haraden's house. The two residences were both built about 1801-1802 and have been continuously used for quarters for over two centuries. In addition to the Commandant and second officer, there were lodgings on the navy yard for the purser and storekeeper.

In the District the wide availability of enslaved labor and low wages paid to free whites and blacks made servants readily available. The wage for a female domestic house worker in September 1810 was $1.00 per week.177 U.S census data reflects nearly all the navy yard officers employed domestic servants. Female domestic workers served officers families as cooks, washers, ironers, nurses, chambermaids and those who collected chamber pots. Some females were employed to provide child care and others as wet nurses. Male domestic workers typically were employed as coachmen, gardeners and butlers. All domestic workers worked in close proximity to the master or mistress of the house and were under constant scrutiny.178 While most domestic workers were enslaved, especially in the first three decades, by the 1840’s free black women appear more frequently in the census enumerations of the District for 1850 and 1860.

177 Records of the District Courts of the United States, Peter Gardner file 0448 June 22 1811 16W3 R9/21/4BX9 NARA RG 21. September 1810 "hire for Negro Milly Hwork -1.00."

178 Rockman, p.138.

There is no complete muster or employee list for navy yard domestic laborers. The documentation we have for such workers is mostly from census enumerations, reward notices, estate inventories and letters. From slaveholders' records, we can infer some of their slaves lived in the attics and outbuildings of the Commandants house and officers’ quarters, while others resided outside in rented small rooms.

The 1820 census enumerates Commodore Thomas Tingey as a slaveholder with his residence as the navy yard. Tingey was counted with six slaves, 2 males less than 14 years, 2 males 26-44 years, 1 female 14-26 years and 1 female 26-44 years. The federal slave census enumerators did not collect any data beyond the number of slaves, their gender and approximate age. The slave schedule forms list slaves as property, and not by name, they remain anonymous with only the surnames of slaveholders. An 1821 reward notice provides some basic information about the identity of one such person:179

Whereas my servant Surrey calling herself Sukey Dean is strolling about the city, or in the vicinity sometimes attempting to hire herself out as a free women asserting she has my assent to do so; neither are true. She is short thick women of a yellow complexion now advancing to forty years of age, is a very good family cook, washes and irons well and understands the management of same - in short if her tongue were safely extracted she would be a most excellent servant. She has been a short time at the residence of Samuel H. Smith Esq. but finding that I assented to her remaining there immediately left. But whosoever will secure her in jail or otherwise of the three days advertisement in the city newspapers sells her at public venue for cash shall have one fourth of what she sells for in full cash less any charges. Thos. Tingey

179 Daily National Intelligencer 16 August 1821.

Sukey Dean, born circa 1780, worked for the Tingey family for at least twenty years as a cook. She is briefly mentioned by Margaret Tingey in a letter of 25 January 1808. Margaret wrote the Commodore that she offered to sell Sukey and her child. She recounted that Sukey stated, "I won’t' go anywhere but where I choose a Master and you cannot oblige me." The Tingey’s did not sell Sukey and eight years afterwards the Commodore makes a casual reference to her in a letter to daughter, Margaret Gay Tingey. Tingey’s 1821 reward notice shows yet another side of their relationship. What happen to Sukey Dean is not recorded.180

180 Margaret Tingey to Thomas Tingey, 25 January 1800, and Margaret Gay Tingey to Thomas Tingey, 15 December 1808. Lewis D. Cook collection of Tingey family letters, Historical Society of Washington. My thanks to Gordon S. Brown for his thoughtful discussion of these two letters.

To date only one woman, Betsey Howard, has been identified on a muster or payroll prior to 1863.181 Howard’s race cannot be conclusively determined, though she is most likely white and possibly a relative of Thomas Howard, Senior, Overseer of the Laborers, and later Clerk of the Yard. District census records reflect black women worked and lived in the Commandant’s House and officers’ quarters as cooks and domestic servants.

181 http://www.history.navy.mil/library/online/wny_payroll1819-1820.htm

A slaveholder’s death was frequently followed by the sale of their property including slaves. Such was the case after the death of Lieutenant Nathaniel Haraden in 1818. Haraden and his family lived on the navy yard in Quarters B, known as "Lieutenant Haraden’s House."182 After the burial service, Haraden’s slaves were auctioned to the highest bidders. Slave auctions such as these resulted in the frequent breakup of whole families, and reverberated throughout the black community. Tragically the fate of the young child listed below was commonplace during this period, as one third of all slave children were forcibly separated from at least one parent:183

Furniture &c

By the order of the Orphan’s Court of Washington county in the District of Columbia, on Wednesday the 22nd inst, at 12 o’clock, will be sold at publick auction, at the present residence of Mrs. Harraden, near the navy yard gate, all personal estate of the late captain Nathaniel Harraden, deceased, consisting of beds, bedsteads, bedding, carpeting, tables, chairs, sideboard, bureaus, looking glass, kitchen ware, silver plate, bed curtains, one fresh milch cow, one gold watch, one sword, and étagère set of china and a mahogany curtain bed set.

Also, a male slave aged about 24 years, and a female slave, age about 19 with her child. The terms will be made known at the time of sale.

SUSAN HARRADEN Adm’n

July 8 - D. BATES auctr.184182 Quarters B Naval History and Heritage Command http://www.history.navy.mil/faqs/faq52-8.htm.

183 Franklin, John Hope Schweninger, Loren, p. 51.

184 Daily National Intelligencer 18 July 1818.

Harraden’s estate inventory names Francis, listed as “Frank,” a 24 year old male and states his value at $450.00. Nancy, possibly Frank’s wife, is the 19 year old female. Nancy and her unnamed six month-old male child are valued at $370.00.185

185 Records of the District Courts of the United States, RG 21, Nathaniel Harraden, file 0684, April 21 1818, 16W3 R9/221, Box 14.

Likewise, following Tingey’s death on 23 February 1829 and his official and elaborate funeral, the family rented thirteen carriages for the funeral procession, the heirs promptly sold much of the estate including his household slaves. The auctioneers provided a short description of these domestic slaves:

They consist of a man who is an excellent coachmen and gardener, a women who is an excellent cook and unencumbered with children and another women, an excellent washer and accustomed to chamber work with a child of five years old, a likely young chamber maid, two boys brought up in the house and accustomed to house work, one about 14 and the other about 11. P. Mauro & Son Auctioneers.186

186 Daily National Intelligencer 31 March 1829.

Tingey’s estate, valued at nearly $12,000.00, contained a lengthy inventory, with notations for all cash received. Among the notations itemized is the sale of the Commodore’s piano for $190.00, and three slaves, Sam, to S. Humphreys for $400.00, Robert to Clements for $275.00 and John to Chris Andrews for $160.00.187 The District census data for the next three decades reflects the continuance of enslaved labor at the navy yard as the major source of domestic workers:

The 1830 census enumerates Commandant Commodore Isaac Hull as having two black freemen in his employ. However, a separate manumission document signed by Hull reflects he purchased John Ambler from Storekeeper, Cary Selden, sometime after assuming command in 1829;

The 1840 census, enumerates Commandant Commodore Thomas H. Stephens as having a total of 54 persons in his household. This number included eight free blacks and two male slaves, ages 24-35;

The 1850 census enumerated Commodore Henry E. Ballard as having six slaves, 1 female age 41, 1 male age 40, 1 male age 28, 1 female age 22, 1 female age 17, 1 female age 7 and 1 female age 6, and

On the 1860 census Commandant Commodore Franklin Buchanan, "a vocal defender of the peculiar institution" and the last Commandant prior to the Civil War, is enumerated. Buchanan resigned his commission in 1861 and later served as Confederate Admiral.188 On the 1860 slave census, Buchanan is enumerated as a slaveholder with five slaves at the navy yard including three females ages 6, 24 and 37. The 37 year old female is noted as "manumitted." Buchanan employed two free black women, Charlotte Cornish, age 23, and Ann Nichols, age 19, both women are listed as domestic servants.189 This 1860 census reflects the demographic trend that two thirds of all District slaves were women.190

187 Records of the District Courts of the United States, RG 21, Thomas Tingey, file 1428, March 10 18298, 16W3 R9/22/4, Box 41 entry 115.

188 Symonds, Craig L. Confederate Admiral, the Life and Wars of Franklin Buchanan, Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 1999, p. 50.

189 See endnote 2, for Thomas Tingey as a slaveholder, for Franklin Buchanan, Eighth U.S. Census for Washington D.C. Ward 6, M 653 _104; page 693: image 129. Eighth 1860 U.S. Census - Slave Schedules Washington D.C., Buchanan is enumerated in addition as having 1 male slave age 30 and 1 male age 10.

190 Pacheco p. 25.

Tables 1 and 2 contain the names of navy yard employees like John Ambler, Daniel Bell, Moses Liverpool and Michael Shiner. These workers gained their freedom only after a long struggle. Their change in status from enslaved to free is reflected in both of these tables. It is important to remember though that, "The vast majority of the people enslaved over the course of history died as they lived - in bondage."191

191 Johnson, Walter, Soul By Soul, Life Inside the Antebellum Slave Market, Harvard UniversityPress: Cambridge Mass. 1999, p. 10.

Table 1 - African Americans employed in the Commandants House and Officers’ Quarters.

One Hundred Dollars Reward “He ran away in June last and had been some time in New York. He is about 5 feet 8 inches high yellow complexion, rather a large round and full eye; and when spoken too sternly gets easily alarmed”…"It is believed he has returned to New York to No. – Wall St"

AKA FrankRecords of the District Courts of the United States, RG 21, Nathaniel Harraden, file 0684, April 21 1818, 16W3 R9/221, Box 14. Records of the District Courts of the United States, RG 21, Nathaniel Harraden, file 0684, April 21 1818, 16W3 R9/221, Box 14. DNI 23 February 1819 23 February 1819 DNI notice of “Garden for Rent, and for Sale, A smart active healthy Negro Boy, 13 years old on the 4th of March next for terms apply to Thomas Tingey.” 19 January 1820 Boston Patriot & Daily Chronicle Reward states Moses, was the property of Wm. Taylor of Norfolk, but rented to Naval Storekeeper Selden at the time of his escape. DNI 1 November 1821 One Hundred Dollars Reward Hay’s born 1802, was sold to the Dove family date unknown and lived on the Yard, where he learned to read. Hays was manumitted in 1843 and later became a minster and teacher. District of Columbia, Department of Education. Special Report of the Commissioner of Education on the Condition of Public Schools in the District of Columbia, submitted to the Senate, June 6, 1868, and to the House, with Additions June 13, 1870, p. 215 National Intelligencer

16 August 1821

Notice offers “reward for my servant” Sukey Dean25 Jan 1808 Margaret Tingey to Thomas Tingey writes. she threatens to sell Sukey and her child. Source: Historical Society of Washington, Lewis D. Cook collection Tingey family letters. 31 March 1829

National Intelligencer“Valuable Slaves. The slaves belonging to the estate of Commodore Thomas Tingey are offered for sale” 31 March 1829

National Intelligencer“Valuable Slaves. The slaves belonging to the estate of Commodore Thomas Tingey are offered for sale” 31 March 1829

National IntelligencerValuable Slaves. The slaves belonging to the estate of Commodore Thomas Tingey are offered for sale. Mother of Five Year old child below.

Five years of age31 March 1829

National Intelligencer“Valuable Slaves The slaves belonging to the estate of Commodore Thomas Tingey are offered for sale.

“Brought up in the House and accustomed to House work.”31 March 1829

National Intelligencer“Valuable Slaves. The slaves belonging to the estate of Commodore Thomas Tingey are offered for sale.

“Brought up in the House and accustomed to House work.”31 March 1829

National Intelligencer“Valuable Slaves. The slaves belonging to the estate of Commodore Thomas Tingey are offered for sale. Brought up in the House and accustomed to House work.” NARA RG21 admin file 1428, 10 March 1829 and, $100., Reward Notice, DNI 9 July 1829 Robert Clarke age 16/17, was sold on Tingey’s death to Charles A. Clements and ran away 12 May 1829. NARA RG21 admin file 1428,

10 March 1829Sam was sold on Tingey’s death NARA RG21 admin file 1428,

10 March 1829John was sold on Tingey’s death.

Isaac HullPurchased from Naval Storekeeper Cary Selden See 17 October 1835. Eighth U.S. Census for Washington D.C. Ward 6, M 653 _104; page 693: image 129. Employee of Commodore Franklin Buchanan. Eighth U.S. Census for Washington D.C. Ward 6, M 653 _104; page 693: image 129. Employee of Commodore Franklin Buchanan. Eighth U.S. Census for Washington D.C. Ward 6, M 653 _104; page 693: image 129 Employee of Commodore Franklin Buchanan.

Isaac HullManumission “Hull himself bought slave John Ambler whom he freed when he left the Yard.” Maloney p. 421.

Toward Freedom 1830 to 1865

During the preceding two decades the number African Americans working at the shipyard declined from a high of 33% of the workforce in 1808 to 7% by 1829-1830 (see Appendix C). After 1830, records for the period 1830 to 1844, of civilian musters, payrolls, etc., are non-existent. Consequently, for this important era, we have only limited glimpses of civilians in naval correspondence, the passing accounts of travelers and newspaper reward notices. By the 1830’s black employment appears greatly reduced and largely confined to the Anchor Shop. What accounts for this dramatic change? Among the major forces contributing to this decline are African American resistance, white opposition to enslaved labor and changes in the navy yard mission and organizational structure.

The rise of anti-slavery sentiment in the late 1820’s is reflected in the growth of movements like the African Colonization Society and abolitionism. During this period, broadsides condemning the sale and keeping of slaves in the District begin to proliferate. At the same time, the campaign for the Congress to abolish slavery in the Capital became widespread. Abolitionist attempts to galvanize public opinion began with the promotion of narratives of enslavement and freedom by former slaves. One of the earliest, by Charles Ball, a former shipyard slave was A Narrative of the life and adventures of Charles Ball, a Blackman, published in 1837. Ball’s story is one of the earliest and served as model for many others to follow. On 23 January 1830 a petition from white workmen in Gosport Navy Yard complained to the Navy Department about the shipyard hiring slaves as stonemasons. “On application severally by us for employment we were refused, in consequence of the subordinate officers hiring negros by the year…”192 Comparable petitions continued throughout the antebellum era.193 In 1839 William McNally, an ex-Navy gunner, published his exposé of the naval and merchant service. Among his charges were that naval officers countenanced and profited from slaves employed on naval vessels and in the navy yards as laborers “to the exclusion of white people and free persons of color.”194 Another writer noted that the employment of slaves at the naval yards had become a source of great complaint, but it is of no use as corruption in this government at the present moment is the order of the day.”195 In response to such criticism, beginning in 1839, the active naval service began to take steps to limit the number of black seamen to five percent and stressed that under no circumstances were slaves to be entered.196 Stung by many critiques, the federal government, with reluctance, dissociated itself from the practice of employing slaves on public projects. Congressional oversight grew and in 1842 the Congress required government agencies to report the number of slaves they hired.197 The Secretary of the Navy, A.P. Upshur, in reply to a question from the Speaker of the House of Representatives said, “There are no slaves in the Navy, except only a few cases in which officers have been permitted to take their personal servants instead of employing them from crews. There is a regulation of the Department against employment of slaves in the general service”198 Upshur went on to carefully note, “neither regulations nor usage excludes them as mechanics, laborers or servants in any branches of the service where such a force is required.”199 The problems presented in verifying such statements are discussed in Appendix D.

192 Tomlins, p. 498.

193 Starobin, Robert S. Industrial Slavery in the Old South New York: Oxford University Press, 1970, p. 143 and NARA Records of the District of Columbia, 8.20 (32A-G5.6).

194 McNally, William, Evils and Abuses in the Naval and Merchant Service Exposed with proposals for their remedy and redress. Cassady and March: Boston, 1839, p. 127. Mc Nally is referring to Norfolk Navy Yard.

195 Liberator, 31 March 1843.

196 Circular, Acting Secretary of the Navy, Isaac Chaucey to Commandant Boston Navy Yard, John Downs, 13 September 1839 “ … in future, not to enter a greater proportion than five per cent of the whole number of white persons entered by him weekly or monthly, and in no instance and under no circumstances to enter a slave.”

197 Starobin, p. 32-33.

198 Secretary of the Navy, A.P. Upshur, to the Speaker of the House, 10 August 1842, Exec. Doc. No. 282, 27th Congress, 2nd Session, volume v.

199 Hulse, p. 528.

Despite official denial, slave labor continued at the navy yard and at other locations. The so called “gentlemen’s agreement” persisted, and slaves were stealthily hired and placed on the books as freemen.200 From court records and the observations of visitors in the 1840’s and 1850’s, slaves continued to work in the blacksmith shop. Blacksmith striker Daniel Bell remained enslaved until he finally purchased his freedom in 1847. Likewise blacksmith striker Anthony Blow worked at the shipyard until he was sold south in 1848 in the wake of the Pearl. Bell and Blow’s names on navy payroll documents have no indication that they were slaves. This practice of unrecorded slave rental agreements was publicly confirmed in 1855, when William F. Jewrix was hired to work in the ordinary with the slaveholder to receive his wages. This subterfuge was only revealed when Jewrix ran away and slaveholder Benjamin P. Smith applied to the Department for the money earned by his slave. The question was then referred to the Secretary of the Navy and finally sent to the Treasury Department for final ruling. The Comptroller of the Treasury ruled Jewrix was a deserter, and in such case his wages were forfeit to the federal government.201

200. Hulse, p. 529.

201 Langley, Harold D. “The Negro in the Navy and Merchant Service 1789-1860” The Journal of Negro History, Vol. 52, No. 4, Oct. 1967, p. 280-281.