African

Americans, Enslaved & Free, at Washington Navy Yard

and Daniel and Mary Bell and the Struggle for Freedom

by John G. M. Sharp

Preface

For African Americans, the Washington Navy Yard was a work place of promise and peril. From rough beginning in 1799, blacks, enslaved and free, were a significant and often a central presence on the yard. Yet their history and contributions to the development of the nation’s oldest federal shipyard have received scant attention. This volume seeks to bring their history to a wider audience and to document their work experiences by using largely untapped naval records and correspondence. It also examines the causes, course and struggle against enslaved labor on a major federal installation. As the first to utilize enslaved labor, many of the Department of the Navy labor policies and practices regarding black employment were first instituted at the Navy Yard, and became models for other federal shipyards.1 One distinct difference between the navy yard and other military installations was that many of the slaveholders were naval officers and senior civilians employed at the yard. While the majority of blacks at the Navy Yard were enslaved, a few free blacks enjoyed journeymen-level wages.2 All of the basic information concerning black employment is etched in the documentary record but has been largely overlooked as the dominant historical paradigm focused on the plantation, thus less notice was given to the urban environment where enslaved labor was exploited in the new urban milieu.3

1 For Gosport Navy Yard later Norfolk Navy Yard, see Upham–Bornstein, Linda, Men of Families: The intersection of Labor Conflict and Race in the Norfolk Dry Dock Affair, 1829-1831 Labor Studies in Working– Class History of Americas, Volume 4, issue , 2007. Mellinger, Caroline Lynne, Public slaves and federal largesse: opportunity, privilege and mechanic opposition at the Norfolk Navy Yard. Madison: University of Wisconsin, 2000, and Tomlins, Christopher L.(1992) In Nat Turner's shadow: Reflections on the Norfolk dry dock affair of 1830-1831, Labor History, 33:4, 494-518. For Pensacola Navy Yard, see Dibble, Ernest F., Antebellum Pensacola and the Military Presence. Pensacola Series Commemorating the American Revolution Bicentennial 3, (Pensacola, FL: Pensacola/Escambia Development Commission, 1974), and Hulse, Thomas, Military Slave Rentals, the Construction of Army Fortifications, and the Navy Yard in Pensacola, Florida, 1824–1863, Florida Historical Quarterly, 88 (Spring 2010), 497–539. For the role of the Army Corps of Engineers in using slave labor for military construction projects, see Smith Mark A. Engineering Slavery; The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and Slavery at Key West, Florida Historical Quarterly, 88 (Spring 2008), 498–526.

2 Appendix A., 1808 Muster of the Washington Navy Yard Prepared for Secretary of the Navy Robert Smith.

3 Slave hiring has attracted less scholastic analysis than other aspects of slavery…, since scholarship is primarily focused on the labor intensive plantation economy of the South. Hulse, p.498-499. Still even in the Navy Yard’s formative years the use of enslaved labor was often the subject of contemporary discussion and commentary with both slaveholders and their critics voicing strong opinions.

An outspoken advocate of slave labor was Navy Yard master blacksmith and slaveholder, Benjamin King. In 1809 King wrote, "Experience has pointed out the utility of employing for Strikers Black Men in preference to white & of them Slaves before Freemen – The Strict distinction necessary to be kept up in the shop is more easily enforced."4 King’s enthusiasm for enslaved labor was not unique. During this era the Navy Yard was "a favorite place to rent out slaves" and to sell them, but quickly became a recognized center of resistance. As early as 1815 the Board of Navy Commissioners (BNC) complained of "maimed & unmanageable slaves."5

4 Benjamin King to John Cassin 14 January 1809 RG45/M125, NARA.

5 Pacheco, Josephine E. The Pearl, A Failed Slave Escape on the Potomac. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2005, p.20. Master Commandant, Nathaniel Haraden, resided on the navy yard in Quarters B from about 1812 to1818. For his sale of slaves on the Yard, see, Daily National Intelligencer 4 February 1817, " For Sale A Middle aged women, with child of two years old; she is a good washer, ironer and plain cook. Enquire of N. Haraden, Navy Yard." Likewise, Daily National Intelligencer 8 January 1817 "For Sale Three likely young stout NEGRO MEN. Apply to N. Haraden, Navy Yard." Master Commandant, Haraden owned numerous slaves. His complaint regarding, "maimed and unmanageable slaves" Haraden to Board of Navy Commissioners 11 May 1815 NARA RG E307 v. 1.

Among the "unmanageable" were freedom petitioners and runaways. In 1812 one young blacksmith helper, David Davis, made his second bid for freedom by running for Baltimore.6 Yet another "servant" John Howard, enslaved to Commandant Thomas Tingey, fled north to Boston on 28 December 1819, where he was seized by slave catchers. In dramatic armed response, a group of African Americans attempted to secure his freedom.7 Likewise, in 1825 Nathan Brown, a young navy yard anchor smith, ran away to the new black Republic of Haiti.8

6 Daily National Intelligencer 2 June 1812, Thirty Dollars Reward Ran away from the Navy Yard on Monday the 28th of May, a Negro man the property of the subscriber, known by the name of DAVID DAVIS; he has been working for the last three years as a helper in the blacksmith’s shop; he is about 25, and 5 feet 10 to 5 feet 11 inches height; some time ago he had his left arm broke a, and lost his fore finger. I will give $ 20 for the apprehending him if taken in the district, or $30 if out of it and lodging him in jail. He was bought of Ed. H. Clavert in Prince George’s county, where he has some friends, and it is probable he will stay about there; he has been in the Baltimore Jail, where I bought him out. All persons are forbid harboring him under a penalty. J.Cassin P.S. Should he voluntarily return to his master, he promises to forgive him. Also see DNI of 14 June 1809 where Davis is described as an "old runaway."

7 Commercial Advertiser 4 January 1820. The Affray, accounts of which have been variously given in different papers in town – originated we have learned in the following manner: A slave belonging to Com. Tingey, has been secured by his agent under the United States Laws, applicable to runaways: but an opportunity occurring, the black was arrested for some debt, real or nominal, and imprisoned. The debt, however, being soon discharged the slave ought in the common course of the proceeding to have been released; but we hear, the agent of Com. T. had applied to one of the Judges of the Superior Court for a writ of Habeas Corpus – the question upon which had not been determined. On Monday evening, six or eight negroes and colored persons armed with clubs and bludgeons - were observed lurking in the vicinity of the jail. And on some further indications of evil intention, being exhibited, two of them were secured in prison by the watch. They had probably assembled for the purpose of taking the slave under their protection when he should be enlarged to prevent his falling into the hands of his master’s agent.

On Tuesday night, about half past ten o’clock a larger body of negroes consisting of 20 or 30 armed in the same manner, were observed to be collected in Court Street. Information being conveyed to the watch – one of whom asking their business, was surrounded at a signal of a whistle, by 20 or more colored people. He was answered in a very imprudent manner, and presently afterwards one of the watchmen was knocked down with a club by a black fellow, who approached him for that purpose. Immediately an alarm was given, and after great tumult and noise about 15 blacks were secured, who next morning were examined before Mr. Justice Gorham, on the charge of an assault; and four of them were bound over to take their trial at Municipal Court on the Monday next. Mr. Fulton, the watchman who was knocked down, we understand is dangerously ill and fears are entertained that he will not recover.

Boston Patriot & Daily Chronicle 19 January 1820, p.

Of the late disturbance near the Jail

Municipal Court

January Term 1820

Commonwealth vs. Wm. Hawkins, and 13 others.The Grand Jury at the last term of the Municipal Court returned a bill of indictment against William Hawkins, and thirteen other colored men, for a riot and for tumultuous and unlawful proceedings on the night of the 28th of December last. The indictment contained four counts, in two of which the parties engaged were charged with being guilty of a riot, and in two others with having unlawfully assembled with clubs and other instruments, and paraded in the vicinity of the jail to the terror of the inhabitants and against the peace.

Twelve of the fourteen were arrested and put on trial in the Municipal Court on Friday last, before a very intelligent and respectable Jury, of whom Samuel P. Gardner, Esq. was foreman.

The testimony showed without contradiction that at about ten o’clock on the night of the28th, of December, twenty or thirty colored men had assembled in the vicinity of the prison, dividing themselves into small squads of two or three, and parading all the avenues leading from the prison – square; and that Hawkins in a particular manner was noticed walking as a sentinel in front of the main gate way. It was in testimony also that most of the persons assembled were armed with large walking sticks or billets of wood, and that most several of them were dressed in a manner calculated for disguise. Some evidence was also given that a whistle appeared to be their signal for rallying; and that whenever it was sounded, those who were within hearing immediately gathered together as if by concert.

It was suggested by the counsel for the prosecution, that the cause of this unusual assembly was the confinement of one John Howard and it was proved that Howard some days before, had been charged before Mr. Justice Parker as a runaway Slave, belonging to Commodore Tingey of Washington, and that by due process of law had been given over to his agent, and by said agent was put on board a vessel bound to Washington; that while he was on board such vessel, five persons of color (among whom two of the defendants) procured writs against him to the amount of $480. And caused him to be arrested and committed to prison. The agent of Commodore being thus deprived of his man, applied to one of the Judges of the Supreme Judicial Court for a writ of Habeas Corpus to obtain Howard as a slave, notwithstanding these writs.

8 Daily National Intelligencer 2 March 1825. "Thirty Dollars Reward Ran Away from the subscriber, on the night of the 19th of February, a Negro Man named Terry (but who calls himself Nathan Brown) about 21 or 22 years of age, about 5 feet, 5 or 6 inches high, of rather a red cast of complexion, with a wide mouth and thick lips; a scar over one eye by a burn, tolerable bushy head. He is a tolerable smith and has worked much at the Anchor Smith business in the Navy Yard. He is artful and plausible in his discourse. I have little doubt that he procured forged papers; as a man answering his description took passage for Baltimore, and having papers signed by two persons, one Trueman Tyler Clerk of Prince Georges County he will make for Haiti, by first chance. He professes to belong to the African Bethel Methodists. He has a variety of clothes so that his dress cannot be well described; they are however generally good and he is fond of being well dressed. Ten dollars reward will be given if taken in the District, and thirty if taken elsewhere, and all reasonable charges paid. JOHN DAVIS, of Abel."

Information about the opportunities to gain freedom moved rapidly among black employees. One surprising avenue to freedom was the legal system. During the early years of the century, enslaved workers such as blacksmiths David Davis and Joe Thompson, Daniel Bell and painter Michael Shiner found methods to seize their limited access to the District court system via petitions for freedom, stating they "are of right entitled to their freedom" and "unjustly detained in Slavery."

Books and articles provided a large reading public vivid accounts of slavery in the new capital. A focus of wide interest was the new shipyard, the District’s largest employer, which quickly became a tourist destination where visitors from around the world came to admire the new industrial technology and to see slavery first hand. One visitor was English author, Lady Emmeline Stuart Wortley. Wortley, writing in the late 1840‘s, marked the prevalence of slave labor at the Navy Yard, "We saw a sadder sight after that, a large number of slaves, who seemed to be forging their own chains, but they were making chains, anchors, &c., for the United States Navy."9

9 Wortley, Emmeline Stuart, Travels in the United States, etc. , during 1849 and 1850 New York: Harper and Brothers, 1851, p. 85.

The decades of the 1820’s and 1840’s saw growing African American opposition to enslavement. The narratives of two men, Charles Ball and Thomas Smallwood, provide vivid accounts of bondage and resistance in the nation’s capital. Charles Ball, enslaved, worked at the Navy Yard for two years as a cook and after several escapes and recaptures made his way to freedom; in 1837 he wrote his autobiography. In his account, Ball remembered life as a slave as "one long waste, barren desert, of cheerless, hopeless, lifeless slavery; to be varied only by the pangs of hunger, and the stings of the lash."10 Thomas Smallwood, author of the Narrative of Thomas Smallwood, Colored Man, Giving an Account of His Birth – The Period He was Held in Slavery – His Release - and Removal to Canada, Etc.: Together with An Account of the Underground Railroad, grew up in the District and worked near the Navy Yard. In 1843, ever the close observer, Smallwood, publically denounced, shamed and exposed a navy officer by name, for whipping an enslaved woman in public. “Is he not a fine specimen of a Naval Commander? Woman - Whipping in the Navy Yard at Washington! ”During the 1840's, he secretly served as an agent of the clandestine "Underground Railroad" where he led many to freedom. In his account Smallwood declared, "[slaveholders] should also remember that justice has two sides, or in other words, a black side as well as a white side, and if it is just for slaveholders to compel men and women to work for them without pay because they are black, and they have the power to do so, then it is equally just for them, or their friends, to deprive their masters of such labor without pay."11 In 1848 two yard blacksmiths Daniel Bell and Anthony Blow helped plan one of the largest and most daring mass escapes of the era.12, 12a.

10 Ball, Charles A Narrative of the life and adventures of Charles Ball, a Blackman. Pittsburgh: Western Publisher, 1854, p, 111.

11 Smallwood, Thomas A Narrative of Thomas Smallwood, Colored Man) Giving and Account of His Birth – The Period He was Held in Slavery – His Release - and Removal To Canada , Etc.: Together with An Account of the Underground Railroad Toronto: James Stephens, 1851, p.19.

12 Josephine E. Pacheco’s The Pearl, A Failed Slave Escape on the Potomac, University of North Carolina Press: Chapel Hill, 2005, and Mary K. Ricks, Escape on the Pearl The Heroic Bid for Freedom on the Underground Railroad. New York: Harper Collins, 2007.

12a. Shane, Scott, Flee North A Forgotten Hero and the Fight for Freedom in Slavery’s Borderland (Celadon Books, New York, 2023), pp.14,, 51, 177-178, 251.

Today these individuals and the events they figured in so prominently are largely forgotten, yet for decades they worked as ship caulkers, reamers, blacksmith strikers, laborers, seamen, cooks, and officer’s "servants." Their toil helped build naval vessels, forged ship anchors, and drove piles for the shipyard wharfs. For the first thirty years of the nineteen century, the Navy Yard was the District’s principal employer of African Americans. Their numbers rose rapidly and by 1808 they made up one third of the workforce.13 The creation of the new yard created economic opportunities for local slaveholders and were quickly grasped by many officers and senior civilians who made handsome profits renting their bondsmen to the federal government. Essential aspects of this history, its extent, scope and the economics of slave and free labor remained, until recently, in largely inaccessible records. The hundreds of enslaved workers of the navy yard remained in relative obscurity for most of two centuries. Reclaiming their history and our shared past is a central theme of this book. This volume examines both the history of African American labor at the Navy Yard and the overall workforce demographic make-up. It provides a discussion of the types of material and documentation available to researchers and scholars. There are two data tables. Table 1 contains information on free and enslaved individuals working directly for the shipyard commandant. Table 2 contains 139 names of individual African Americans, their occupation, status and related employment information, with a brief narrative of the shipyard’s black workforce from 1799-1865.

13 There are four histories of the Washington Navy Yard: Hibben, Henry B. Navy-Yard, Washington. Washington: Government Printing Office, 1890, Peck, Taylor Round Shots to Rockets A History of the Washington Navy and U.S. Naval Gun Factory. Annapolis: Naval Institute, 1949, Marolda, Edward The Washington Navy Yard: an Illustrated History. (Annapolis: Naval Historical Center, 1999) and my History of the Washington Navy Yard Civilian Workforce 1799-1962. Stockton, CA: Vindolanda Press, 2005.

https://www.history.navy.mil/research/library/online-reading-room/title-list-alphabetically/n/navy-yard-washington-history-hibben.html Henry Hibben‘s account contains no references to black employees and reflects the post-Civil War moratorium or any mention of slavery. Taylor Peck has a brief discussion of the BNC order to discharge all slaves, p.42, and Secretary of the Navy, Smith’s correspondence with Commodore Thomas Tingey regarding "servants," p. 74, Edward Marolda provides extracts from the Diary of Michael Shiner p. 22-24. My own account of the Navy Yard civilian workforce, discussion of race relations is pages 16 -17 and Appendix B has Isaac Hull’s 1829 letter and his separate report on the employment of slaves. The civilian employee population in 1808 was 194 employees with 64 African Americans of which 6 are listed as free.Transcription

This work required extensive transcriptions of microfilm and photographic images of muster and employee lists from the collections of National Archives and Records Administration and the District of Columbia Archives. I have striven to adhere as close as possible to the original in spelling, capitalization, punctuation and abbreviation (e.g. "Do" or "do" for ditto or same as above) including the retention of dashes, ampersands and overstrikes. Racial designations such as white man, black, etc., are those used in the original documents. Where I was unable to print a clear image or where it was not possible to determine what was written, I have so noted in brackets. Where possible, I have attempted to arrange the transcribed material in a similar manner to that found in the letters and enclosures. All transcriptions of documents quoted are mine. Please remember that many of the historical documents and excerpts cited below were created during the nineteenth century and reflect the predominant attitudes and language used at the time.

Acknowledgements

This history would not be possible without the many scholars who have begun to reexamine the history of enslaved workers in the District of Columbia. Among them, Bob Arnebeck has led the way with his superb and insightful study, The Use of Slaves to Build the Capitol and White House 1791-1801.14 The White House Historical Association’s History of Slave Laborers in the Construction of the United States Capitol has provided valuable research on the utilization of enslaved labor at the White House. The District of Columbia’s largest employer, the Washington Navy Yard, has been studied by Dr. Edward Marolda in his excellent The Washington Navy Yard an Illustrated History.15. In the course of researching, transcribing, compiling and writing this account of African Americans at the Navy Yard, I have incurred many debts of gratitude to numerous individuals and institutions. First I owe a special debt to my longtime friend Mr. Charles Johnson, Archives Specialist (retired), National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, DC. As he has done for so many researchers, he has always graciously shared his expertise and patiently answered my many questions. Guided by a proverbial sixth sense, no matter how obscure the reference, Charles Johnson always found the document. Thank you Charles! Profound thanks also to my colleague, Ms. Connie Finney-Dunwell, Human Resources Specialist, Washington Navy Yard (retired), who helped with the early research at the National Archives and for her support over the years.

14 Arnebeck, Bob, Use of Slaves to Build the Capitol and White House 1791-1801 http://bobarnebeck.com/slaves.html, retrieved by the author 14 August 2010.

15 Among the most useful works on the employment of enslaved labor: Allen William C. History of Slave Laborers in the Construction of the United States Capitol , U.S. Government Printing Office: Washington, 2005, Arnebeck, Bob Use of Slaves to Build thhe Capitol and White House 1791-1801, chapter three, accessed http://bobarnebeck.com/slavespt4.html., Brown, Letitia W. Free Negroes in the District of Columbia 1790-1846: New York: Oxford University Press, 1972, Green, Constance McLaughlin, The Secret City: A History of Race Relations in the Nation's Capital. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1967. Washington: A History of the Capital 1800-1950. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1962. The Economic Position of Free Blacks in the District of Columbia. The Journal of Negro History 58, No. 1. (Jan. 1973): 61-72. The White House Historical Association, African-Americans and the White House, http://www.whitehousehistory.org/whha_timelines/timelines_african-americans-01.html accessed by the author 3 September 2010. Marolda, Edward J., The Washington Navy Yard, An Illustrated History, (Annapolis, Naval Historical Center, 1999)

My friend Glenn E. Helm, Director of the Navy Library, was ever helpful with advice and encouragement for this project. As he has done for so many times, Glenn generously made the resources of that wonderful institution available. A. Davis Elliott, Navy Department Library, provided outstanding help and expertise in making this web-page-ready. Gail Munro, Head of the Navy Art Collection, Navy Museum, graciously provided me an advance copy of her superb transcription of the records of 4th Street Ebenezer Methodist Church and shared her vast knowledge of the religious community of Washington. My thanks to Gordon S. Brown, author of The Captain Who Burned His Ships: Captain Thomas Tingey, USN, 1750 - 1829. Gordon gave me the benefit of his in-depth research into Thomas Tingey’s remarkable tenure as Commandant. Mary K. Ricks, author of the superb Escape on the Pearl, The Heroic Bid for Freedom on the Underground Railroad, kindly answered my questions regarding Thomas Smallwood. My description of Smallwood’s abolitionist activities in Washington, D.C. is drawn from Stanley Harrold’s brilliant Subversives Antislavery Community in Washington, D.C., 1828-1865. Seth Rockman’s Scraping by Wage Labor Slavery, and Survival in Early Baltimore, although focused on Baltimore, inspired me to rethink many ideas regarding labor and race while providing new insights into the lives of the working poor and day laborers. Shane Scott’s 2023 riveting, Flee North a Forgotten Hero and the Fight for Freedom in Slavery’s Borderland provided me many new insights into the heroic Thomas Smallwood as an abolitionist and liberator.

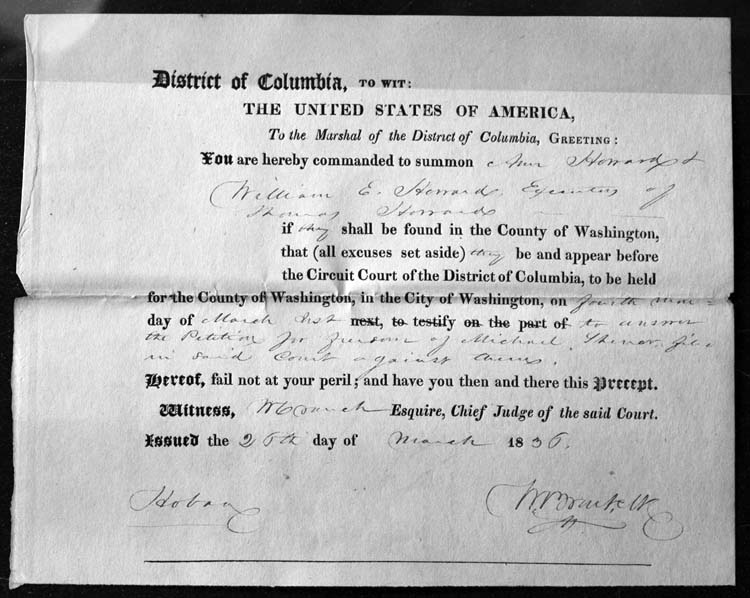

Alexandria librarian and genealogist Leslie Anderson’s presentation "The Life of Freed Slave Michael Shiner" on Cspan3 was both fascinating and exciting. Leslie’s account of his life included news of her important discovery of the 26 March 1836 Petition for Freedom. This document gave me both new insight and a better understanding of Shiner’s long struggle for freedom.

My discussions with noted author Tonya Bolden have been enormously helpful and thought-provoking. Tonya, the author of the forthcoming Michael Shiner’s Capital Days, has generously shared her ideas regarding Michael Shiner and his compatriots. I have benefited greatly from her thought-provoking questions, keen intelligence, humor and generosity. Her work added considerably to my understanding of Shiner’s life and I am greatly in her debt.

Ali Rahmann, Archivist, District of Columbia Archives, answered my pleas many times by locating the manumission and freedom certificates so important in this study.

My particular thanks to Robert Ellis, Archivist, and Chris Killillay, Archives Specialist, at National Archives and Records Administration, for their extraordinary support. Mr. Ellis found both the 1834 inventory of Thomas Howard’s estate and his 1836 Petition for Freedom filed by Michael Shiner in the Circuit Court of the District of Columbia. These documents changed my narrative, for they demonstrated a more active and determined Michael Shiner than I had previously imagined. His work on the District of Columbia court system vastly improved my understanding of the whole petition process. Mr. Killillay helped me locate those rare but significant mentions of enslaved individuals contained in the Washington Navy Yard Station Logs. Both cordially gave me their valuable time and unrivaled knowledge of this wonderful institution’s incredible resources.

Despite the kind help and assistance received from many friends and colleagues, any historical inaccuracies remain on my shoulders alone and I assume full responsibility for them.

This book is for Gene uxori meae carissima.John G. Sharp

Introduction

This account of the Navy Yard’s African American workforce, 1799-1865, is the first to examine the history and demographic make-up of the Navy Yard and to survey the various kinds of documentation available to researchers and scholars. Here readers will find two data tables: Table 1 contains the names of free and enslaved blacks employed as domestic servants for the Commandants and naval officers assigned to the Yard; Table 2 contains 139 names of individual African Americans, their occupations, wages and related information. Table 2 also contains the names and related information for 78 slaveholders. More than any other source, Michael Shiner’s Diary remains the most important.

Shiner came to work at the yard about 1826. Consequently his chronicle does not cover the crucial first two decades, the formative period when black employment was at its height. His account is unique and important since it is one of few by an enslaved shipyard worker and contains key evidence about the lives and treatment of black workers. Scholars especially note the 1833 abduction of his family by slave dealers and the treatment of black caulkers during the crucial 1835 strike. Many of Shiner’s references pertaining to the treatment and discipline of slaves and free workers help clarify day to day labor policies and practices; it quickly became apparent that, to fully understand the various references and allusions to his friends and fellow slaves, the inquiry needed expansion. One of the results is two data bases: Table 1, African Americans Employed in the Commandant's House and Officers’ Quarters, and Table 2, African Americans Employed on the Navy Yard rolls 1799-1865. Together, these two tables have over two hundred individual entries for African American employees. These are data bases designed to provide basic information on people heretofore largely anonymous and to give them identity. Information and source citations are provided for each employee. Additional information regarding many of these employees is in the endnotes. A brief history of African Americans at the Navy Yard 1799-1865, is included to give some idea of the events during these crucial years. Appendix A is a transcription of the 1808 muster of the workforce, while Appendix B is a transcription of the 1808 Muster of the Ordinary. Appendix C is an 8 April 1830 letter from Isaac Hull to the Board of Navy Commissioners with a list of African Americans employed at the Navy Yard. Appendix D is a transcription of the Painters Department payroll 1 to 15 September 1854. Appendix E is a transcription of an important 9 January 1821 letter from Thomas Tingey to the Board of Navy Commissioners listing the wages paid to Navy Yard mechanics and laborers from 1801 to 1820.

* * * * * * * * * *

History of African Americans Enslaved and Free on the

Washington Navy Yard, 1799-1865Slavery and Patterns of Employment in the District of Columbia

In the new Capitol, patterns of federal employment were set early. Workers, white and black, came from all over the country to make a fresh start, drawn by the promise of steady work or to just try their luck. Most of the skilled work for the Capitol went to white workers.16 Beginning in 1792 the District Board of Commissioners, charged with overseeing the construction of public buildings, began hiring construction workers; they also made the decision to hire enslaved laborers. On average the Commissioners hired 50 to 100 slaves each year; moreover they hired some free blacks as laborers and paid them the same wages as whites. The Commissioners, composed solely of slaveholders, conceived enslaved labor as "a very useful check & kept our Affairs Cool," a useful check, that is, on the wage demands of free laborers.17 In the 1790’s District owners were paid $60 to $70 a year for the rental of their bondsmen, the same wage paid unskilled white laborers. The Commissioners' decision to hire blacks caused no public comment in 1792, for slavery was a legally recognized and sanctioned institution. Not surprisingly the District employment market closely mirrored its neighbors, two of the largest slave holding states, Maryland and Virginia. The District quickly adopted most of its legal code from Maryland, including its slave laws, which remained in force until 1862. Additional laws governing blacks were continually added to what became the "Slave Code of the District of Columbia."18 Despite the Code, free African Americans were attracted by promises of work in the construction boom and by a comparatively lower cost of living. District laws created a somewhat freer environment in contrast to Maryland and Virginia. In Washington wrongly imprisoned slaves, at least in theory, could recover their freedom in court, a protection not afforded in the neighboring states. More importantly the new District had no requirement for free blacks to leave the District after a set time as in Virginia. In comparison to the Southern States, the District’s slave code, though moderate, still placed onerous and burdensome restrictions on all African Americans.19

16 Arnebeck, Bob Through A Fiery Trial: Building Washington 1790-1800. Lanham, Maryland: Madison Books, 1991, p. 141, 143-144.

17 For the "useful check of slave labor on white employees" see: Thomas Johnson, David Stuart and Daniel Carroll, Commissioners to Thomas Jefferson, 5 January 1793, Commissioners Letter book Vol. I, 1791--1793, NARA RG, and for wage difference between Charlestown and Washington see Maloney, Linda M. The Captain from Connecticut: The Life and Naval Times of Isaac Hull. Boston: Northeastern University Press, 1986, p. 421. The best discussion of this important letter is found in Arnebeck’s The Use of Slaves to Build and Capitol and White House 1791-1801 http://bobarnebeck.com/slaves.html.

18 Slave Code of the District of Columbia, Library of Congress http://memory.loc.gov/ammem/sthtml/stpres02.html accessed by the author 20 January 2010.

19 Melder, Keith E. City of Magnificent Intentions, A History of Washington, District of Columbia. Intac Publishers, 1997, 59.

By the 1790’s the use of enslaved labor had a well-established record in the local building trades. Initially most blacks in the District were enslaved. Owners from the surrounding communities actively sought to rent out their slaves to the building contractors or the new federal government; the returns to the owners were relatively high. One reason for the slaveholder’s enthusiasm in the new city was that agriculture in the middle states did not lend itself as readily to large scale plantations. Numerous blacks were brought in by slaveholders during the District’s opening building surge of 1792-1801, and throughout this time there was an acute shortage of labor and capital. The majority of black labor came from Prince Georges County Maryland, a region particularly hard hit by decline in tobacco cultivation.

Slaveholders rapidly moved to hire out their bondsmen in the new city. During these years Michael Shiner and Daniel Bell, both from Prince Georges County, were rented out to the Navy Yard. In the period 1800-1830 some slaveholders, faced with declining tobacco revenue, manumitted their slaves. However suspicion of a large presence of black freemen led rural areas to enforce black codes of ever greater severity and free blacks to move into the District.20 During this same period, the basic pattern for the federal work was set by the Commissioners and the renting or leasing of slaves to work alongside free white and black workers remained constant for the first three decades. This active rental market in enslaved labor gave "the peculiar institution" a resilience, flexibility, and, most of all, a profitability in the new metropolis.

20 Meyer, Gibbs Pioneers in the Federal Area: Records of the Columbia Historical Society, D.C. Vol. 44/45, 1942/1943, p. 139.

The total population of the District in these years was small. In 1800 it comprised only 14,093 inhabitants, of which 3,244 were enumerated as slaves and 783 listed as Free Negro. By 1860 the District of Columbia was home to 11,131 free blacks and 3,185 slaves.21 As the urban population grew, the number of free blacks swelled and with each passing decade economic opportunity for black workers, both enslaved and free, expanded while some white laborers, viewing this intense demographic shift, began to voice alarm.

21 Green, Washington: A History of the Capital, 1800-1950., p. 21.

The construction of the Navy Yard in 1799 expanded the need for skilled and unskilled labor. Many of the District slaveholders had supplied workers to the White House and Capitol construction. In the creation of the Yard, slaveholders saw opportunity for further profit from renting bondsmen to the new Yard. Indeed the first substantial structure built, the Wharf, was likely built by slaves. The man who directed this development, Samuel N. Smallwood, later the first elected mayor of Washington D.C., began his career in the District as overseer of slaves at work building the Capitol. In August 1799, Smallwood had "30 to 40 men carting dirt" to the new Navy Yard wharf.22 As mentioned above, information on the Yard’s first decade is limited; we have only a fragmented employees' register which is dated 1806. This document enumerates 148 names with just four clearly identified as enslaved.

22 Arnebeck http://bobarnebeck.com/slavespt4.html

Washington Navy Yard in 1808

The 1808 employee musters are our first and most complete picture of Navy Yard employment. Next they reflect the growth of enslaved labor. The impetus for these musters was the Embargo Act of 1807 and the subsequent "Nonintercourse Acts" which restricted American ships from engaging in foreign trade. These acts led to the War of 1812 between the U.S. and Britain. The embargo was a financial disaster for the Americans because Britain was still able to export goods. The embargo led to a severe tightening of the department’s appropriation. The Navy anticipated reductions in its manpower, afloat and ashore, with the further likelihood that out-of-work seamen would soon enter federal shipyards in large number pleading for employment. Concerned his department would have little to offer them, Secretary of the Navy, Robert Smith, wrote to Commodore Thomas Tingey on 21 April 1808 and gave him direction to draw up a muster and make plans to reduce his workforce at the Yard. Tingey was told to provide Smith a comprehensive list of all employees and to "send me a muster roll of all persons of every description employed in the Yard … in case of blacks whether they be free or Slaves &c and, where they were slaves, the persons to whom they respectively belong…"23 The Commodore replied that he had a total of 194 employees in the yard and "in ordinary"; this total included 58 slaves and six free blacks, or 32.9% of the total workforce (see Appendix A). The majority of these employees were blacksmith strikers, ship caulkers and carpenters laborers. The six free blacks are all enumerated as ship caulkers, a trade they quickly came to dominate.24

23 Smith to Tingey 21 April 1808. Navy Department, Letters, 1808 Miscellaneous Records of the Office of Naval Records and Library, Record Group 45, Roll 0175, p.16, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C.

24 1808 employee listing reflects the majority of caulkers and reamers as African Americans, see Appendix A.

"…well known to be established custom…"

Secretary Smith was familiar with the navy yard and his office was only a mile from the yard gates. Smith, a lawyer, was skeptical of the muster and followed up, pressing the Commandant for more detail and employment data. On 19 May 1808 Tingey forwarded a separate muster for the ordinary (see Appendix B). That same year on 3 October 1808 Samuel Hanson, WNY 1804-18011, and a slaveholder himself, accused Commodore Thomas Tingey, his deputy John Cassin and Naval Purser Joseph Cassin of various misdemeanors.24a One offense angered Hanson and greatly trouble Secretary of the Navy, Robert Smith. The alleged offense was Navy Yard officers and civilians, allowing subordinates and family members to profit by placing enslaved workers on Navy payrolls. This explained Hanson was a blatant subterfuge. The ploy being the slaveholders unlawfully signed for and collected their enslaved “servant’s” wages. Hanson was particularly incensed because Naval Purser Joseph Cassin (below) was the son of John Cassin.24b

It is a common practice to permit the Favorites of the Yard, to have Slaves from Persons in the Country and have them entered on the Rolls as their own. The usual price given to the Master is $10 per annum while the favorite receives from the U.S. for him 75 cents per diem. Joseph Cassin has generally 2 or 3 of this description. The job is to him particularly gainful, because after speculating on the owner, he sometimes speculates on the poor Slave himself, by agreeing to receive from him a certain sum (say $10 per month) and giving up to him the remnant of the wages for the purpose of procuring sustenance which the Slave, naturally indeed, almost necessarily purchases of his new Master. It is probable that no speculation on the Master has actually taken place since it is believed the Slave would not be received into the Yard except through the medium of the Favorite, whose interest and not that of the permanent owner, is consulted in this circuitous and insidious operation.

4a Navy Court Martial Records and Court of Inquiry, 1799-1867, re Thomas Tingey, John Cassin and Samuel Hanson, 10 Dec 1808, Volume 2, p. 27, Case number 55, Case Range, 30-74, Year, Roll 0004, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington D.C.

24b Brown, Gordon S., The Captain Who Burned His Ships: Captain Thomas Tingey, USN, 1750 -1829 (Naval Instiutue Press, Annapolis Maryland, 2011), p. 65.

The naval system for storing ships "in ordinary" at shipyards was for vessels held in reserve or for later need. Normally these ships had seen hard service abroad and were awaiting restoration but due to the small naval appropriations of the era repairs were not possible. Ships in ordinary typically had small or minimal crews comprised of semi-retired or disabled sailors who stayed aboard to ensure that the ship remained in usable condition, provided security, kept the bilge pump running and ensured the lines were safe. Only a few surviving musters for the ordinary have any specific reference to color, ethnicity or servile status. What makes the 1808 muster unique is Smith’s insistence that all free and enslaved blacks be enumerated. Officially, blacks enslaved and free were excluded from the military service. In August 1798 Secretary of the Navy, Benjamin Stoddert, had sent out an order forbidding "Negroes or Mulattoes" enlistment in the Navy. In practice the enforcement of this regulation was left to the discretion of Commanding Officers, especially aboard ships.25 At the yard both white and black seamen comprised the ordinary, but many of the African Americans enumerated on surviving musters as "ordinary seamen" were not free volunteers for naval service, but bondsmen rented by individual slaveholders to the Navy Yard. These slaveholders were a mixed group of shipyard officers, senior civilians and other citizens of the District of Columbia. An early confirmation of the hire of enslaved workers into the Navy Yard ordinary is found in a letter dated 10 July 1806 from Captain John Cassin to the Secretary of the Navy. Cassin begins by acknowledging a previous "order to discharge all slaves in ordinary." He then proceeds to relate "we are so much reduced and not able to man a boat … seamen cannot be obtained at present wages, I would therefore suggest to you the propriety of employing a few slaves in the ord[inary] as I think they will answer for many of our purposes as seamen."26 Slaves assigned "in ordinary" performed many of the most unpleasant and onerous jobs.27 For example, the Station Log entries for the week of 15 January 1827 reveal the men were assigned to scrape the hull of the ship Potomac, move timber from the saw mill and help suppress a large fire at Alexandria.28

25 Secretary of the Navy Benjamin Stoddard to Lt. Henry Kenyon, 8 August 1798, Naval Documents Related to the Quasi-War Between the United States and France, Washington, 1935, I, p.281. "No Negroes or Mulatoes are to be admitted, and as far as you can judge, you must be cautious to exclude all Person whose Characters are suspicious."

26 Cassin to Smith 10 July 1806 RG45/M125 NARA.

27 During the war of 1812, many of the yard mechanics were called out as part of the militia to help defend the capitol. "A few ordinary men, chiefly blacks, remained at their posts during the difficult and trying times culminating in the burning of the Navy Yard on 24 August 1814." American State Paper: Documents Legislative and Executive, Part 5. Volume 1, Congress of the United States, Washington DC: Gale and Seaton, 1832, p. 532.

28 Washington Navy Yard Station Log 1822 -1830, RG 181, NARA 15, 10 January 1827.

The navy had quickly come to rely on enslaved labor. On 18 May 1808 Captain Cassin again wrote Smith to plea for its retention:

Understanding it is the intention of the Secretary of the Navy to discharge all Slaves employed in this Yard, I beg leave to show there are but very few white men in this Neighborhood that can be found to fill the places even for one fourth higher wages. We have also in the Black Smith Shops thirteen firemen, consequently they require Thirteen independent of the Anchor Shops, which also require Six Blowers at 85 cents per day should these men now employed be discharged. We should be compelled to bank off six fires and turn these six firemen as strikers from 150 to 170. Two White men left the Shop last week on account of the wages they received 100 D per day and were not satisfied. It is also necessary we have from three to five Laborers to attend the Calkers (Caulkers), one to attend the stuff, the others to clean before the Calkers and whose wages have not exceeded one half the Calkers, the former belonging to the men in the City but unfortunately free to say no.29

29 Cassin to Smith18 May 1808, RG45/M125 NARA.

Commodore Tingey’s reluctant response to curtail the use of slaves reflects the prevalence of the rental of chattel labor in the various shops and aboard naval ships as seamen, cooks, and laborers.30 The creation of the Navy Yard combined with employment precedents set by the District Commissioners may well have inspired many small slaveholders to purchase additional slaves. The 1808 Muster illustrates that such rentals were lucrative, allowing naval officers to supplement their pay by drawing the wages and rations of their enslaved "servants". His reply enumerates an additional 52 people, including fifteen more enslaved individuals, ten of whom were owned by naval officers including Seaman Abram Lynson, the Commodore’s personal "servant. Tingey, citing the custom of the service, implored Smith to reconsider his ban:

It is well known to be established custom, that whenever an officer has been ordered on duty - so, as to give him

the command of men, entered on the muster roll for pay &c said officer hath invariably entered thereon one or two at least of his own servants or taken such servants from the men so entered - It would appear then Sir - singular and tend to excite unpleasant feelings, were myself and the Officers under my command at this place, to be the only exceptions to the customary indulgence - An indulgence also common to every officer, in the Military and Marine service and generally in number according to Rank. It is therefore hoped with submission, by myself and Officers attached to this yard, that you would please to take this matter into consideration - and sanction to us the indulgence common to all our brother officers here to be allowed service and the quantum to each.3130 McKee, Christopher A Gentlemanly and Honorable Profession The Creation of the U.S. Naval Officer Corps, 1794-1815 Naval Institute Press: Annapolis, 1991, p. 331-337 and 660-661. McKee notes the naval custom of officers entering their slaves on the muster roll of ships as members of the crew – seaman, ordinary seaman, or boy but employing them as shipboard servants, signing for their wages and pocketing the slaves pay. Apparently the custom was wide spread, but poorly documented; Tingey’s correspondence with Smith provides the most detail. For naval officers "rations" included food, clothing and candles.

31 Tingey to Smith 19 May 1808. RG45/M125, NARA.

"Unpleasant Feelings"

For his part Smith would not be swayed; he informed the Commandant that the practice must end informing him, “There exists no law which warrants the indulgence asked, nor does usage either of the Army, Navy or Marine Corps sanction such indulgence nor cannot I permit the introduction of a rule without precedent, or any apparent necessity. The Servants in question must therefore be immediately discharged.”32a

32a Tingey to Smith 26 May 1808, Letters Received by the Secretary of the Navy “ Captains Letters” , 1 Apr 1808 -28 Jun 1808, Letter Number 85, Record Group 260, Roll, 0011, p.1, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington D.C.

Reluctantly, Tingey signaled his compliance on 26 May 1808, writing he had removed the slaves in ordinary and let Smith know: "I cannot dissemble that I experienced some unpleasant feelings at having asked an indulgence that cannot be complied with - especially as the officers of the Yard, would be well satisfied, to be only on an equality (or even nearly approximating thereto) with those around us, not immediately attached to the Yard."32b

32b Smith to Tingey, 25 May 1808, Navy Department, Letters, 1808 Miscellaneous Records of the Office of Naval Records and Library, Record Group 45, Roll 0175, p.25, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C.

Smith, though critical of officers placing their "servants" on the Navy payrolls, was not opposed to slavery per se; rather his directions to Tingey were probably motivated by a genuine concern that naval officers were drawing public money for their slaves' pay and rations. Equally, Smith can be seen as anticipating his department needs for jobs in the ordinary for seamen put ashore due to the embargo.

In 1809 the Navy Secretary, Paul Hamilton, reversed Smith and approved the request below "for a few slaves in the Ordinary" because of the shortage of white seamen:In consequence of an Order to discharge the Slaves [in ordinary] Some time past. We are so much reduced as not be able to man a boat or even to wash the Decks of one of the Ships. As Seamen cannot be obtained at the present wages, I would therefore Suggest to you the propriety of employing a few Slaves in the Ordin[ary] as I think they will as Effectively answer for many of our purposes as Seamen …. John Cassin33

33 Cassin to Hamilton, 10 July 1809. RG45/M125, NARA.

Although the reasons offered varied, requests for slave labor continued to be a regular occurrence for the next three decades.

The African American Workforce in 1808

The 1808 figures are composed from two muster rolls and provide fascinating glimpses of the African American workforce. Commodore Tingey reported 179 employees: 43 enslaved and 6 free blacks and, in a subsequent report, noted an additional 15 working in the ordinary or 32.9% of the workforce. These two muster rolls reflect that most slaves worked in the blacksmith shop as strikers or, with the shipwrights and carpenters, as carpenters laborers, and ship caulkers; some worked as ordinary seaman and a few were apprenticed in skilled trades. Among these were David "Davey" Gardner, apprenticed to master mast maker and slaveholder Peter Gardner, and Edwin Jones and William Oakley known as William Fox, both enslaved and apprenticed to master shipwright Josiah Fox. Peter Gardner was paid $1.80 per day for Davey’s work. Tom, a blacksmith apprentice enslaved to master blacksmith, Benjamin King, was paid $1.00 per day; the same wage as white apprentices but his money went directly to King’s pocket.34

34 Early muster rolls contained a signature block beside the employee’s name, free employees white and black signed or made their X as acknowledgement of receipt. Apprentices and enslaved workers’ wages were signed for either by the apprentice’s master mechanic, the slaveholder or the slaveholder’s agent. The 1811 Muster Roll is the best surviving of such documents: Benjamin King, for example, signs for his slave apprentice Tom Macom. John Davis of Abel also signs for his slaves, John Smoot and John Legree, while Overseer of the Laborers, Thomas Howard, signs for enslaved laborer Bill Barnes. The wages of Toby Forrest and Bill Smith are signed by Maria Shanley, acting for slaveholder Elizabeth Magruder, see http://genealogytrails.com/washdc/wny1811.html accessed by the author 25 March 2010.

How did enslaved labor become such a prominent part of the workforce? Slaveholders rarely explained how they acquired their slaves or how they managed to place them on the shipyard payroll. One who did was master mastmaker, Peter Gardner. In 1808 Gardner wrote to the Secretary of the Navy, Robert Smith 1757-1842, and provided his rationale for the employment of enslaved apprentice mastmaker, David "Davy" Gardner.

About the latter part of the year 1803, your memorialist was requested by Samuel H. Smallwood (who’s certificate is hereunto annexed) to take his negro man into the Mast Shed that he might be instructed in the Mast making business, in consequence whereof & at the special order of Capt. Cassin, your memorialist took him into his shed. For the first three or four months, the said Davy received 75 cents per diem; but his improvement was such that his wages were afterwards raised to one dollar per diem, of which first augmentation of wages the said Smallwood and not your memorialist received the advantage. All of which matters and things will appear by a reference to the certificate above mentioned

Seven months after the entrance of the said Davy, to wit in the August 1804, he was bought by your memorialist & continued in his constant profession in constant employment at the mast making business until the time when the first letter of the 21st of August 06 was written by your memorialist. At the time the letter was written by your memorialist, no regulations existed for augmenting the wages of apprentices by the custom of the Navy Yard, a discretionary power vested in the superintendent of the Navy Yard, Capt. Cassin, of augmenting the wages of apprentices according to their skill and improvement, and to the time they too worked in their employment. The said Davy at the time, the date of the said letter, had worked as an apprentice in the mast making business nearly three years and during that time had acquired the reputation of skillful industrious workmen. In consequence of which circumstances, your memorialist, conceiving that the said Davy was justly entitled to an augmentation of wages wrote the letter above mentioned to the said Josiah Fox requesting the wages of the said Davy might be augmented, but not withstanding - the representations made in said letter, the wages of the said Davy were not at that time increased, nor was the letter ever acted upon.35

35 Peter Gardner to Tingey 29 June 1808 RG45/M125, NARA.

Gardner clarifies that Samuel H. Smallwood, a powerful presence in the District, the former overseer of slave labor at the Capitol and future mayor, "requested" he take Davy into the Mast Shed. Further Gardner carefully notes Davy’s hire was specifically approved by second officer Captain Cassin.

White mechanics bitterly resented the practice of the admission of blacks as apprentices in the skilled trades. In March 1811 a committee of shipwrights wrote the command on behalf of themselves and the other trades. In their letter they remonstrated "against the practice of master workmen admitting black or colored slaves as apprentices to the master workmen & those allowed the privilege of apprentices." They stressed they considered "such practices as degrading to their profession, inasmuch as parents who may have children to put out will think it disreputable to bind free children in contract with Negro slaves."36a

36a Tingey to Hamilton 19 March 1811, Letters Received by the Secretary of the Navy “Captains Letters” 1 Jan 1811 -31 May 1811, Letter Number 143 Record Group 260, Roll, 0021, p.1, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington D.C.

From the dates of their respective letters both men had met earlier that morning to seek a way to mollify the Navy Yard a grieved white mechanics. Secretary Hamilton responded to Commodore Tingey thus: “I have received your letter of this days date. You will discharge all the Black mechanical apprentices of the Yard other than the Caulkers & Smiths.”36b

36b Hamilton to Tingey, 19 March 1811, Navy Department, Letters, 1811, Miscellaneous Records of the Office of Naval Records and Library, Record Group 45, Roll 0175, p.14, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C.

The Enslaved on the Payroll

Most employees at federal shipyards were per diem, that is compensated for the day with no promise of more work in the future. This form of contingent work was based on a twelve hour day, six days per week, with time allotted for lunch and breaks. While shipyard work followed a set pattern, employees lived with a great deal of uncertainty. For most employees the wage rate, while important, was often secondary to the number of days they could string together. For mechanics and laborers, day labor meant there was never any guarantee of a full week's work. The Navy typically followed the practices of private shipyards; personnel were hired when there were sufficient funds. The Yard force downsized after decreases in naval appropriations and during winter months when the Potomac River froze or weather conditions constrained outside labor, leading to sustained periods of forced idleness. The enslaved worked the same hours as free employees; they labored alongside free employees, white and black, and performed many of the same tasks. Most toiled as blacksmith strikers and assistants, wielding heavy hammers to shape and beat super-heated metal into anchors or chain, while others worked with the carpenter’s crew, moving and loading heavy deck planking, nails and tools for the white journeyman carpenters. Some of those assigned to the carpenter crew worked as sawyers stationed top or bottom in a saw pit cutting large pine and oak logs into planking. The 1808 ship caulkers were mostly African American except John Hebron, master caulker, and his three white journeyman caulkers. All the white journeyman caulkers were paid the same wage as their free black counterparts. The 1808 muster includes the brothers Aaron and Andy Davis, young "oakum boys". The oakum boys were assigned to pick apart old hemp ropes which the ship caulkers then used to insert between the planks of a ship to make it watertight. Caulking was typically done with a special hammer or wedge, then hot pitch was poured on the oakum and a hot caulking iron applied tar to seal the seam. Aaron and Andy’s duties included keeping the ship caulkers constantly supplied with oakum to place between the ship planks. Later, apprentices had to be at least 14 to work in the Yard; however Aaron and Andy may have been a great deal younger.37

37 BNC Circular to Shipyard Commandants 1 May 1817.

While much depended on the disposition of the individual slaveholder, slaves in the District and in the Navy Yard typically enjoyed greater independence and better prospects for liberty than those laboring on farms or plantations further south. In Washington D.C. with no tobacco, cotton or wheat crops to gather, many owners found it profitable to rent out their bondsmen to the yard. Workers, thus rented out, in essence had two masters; the slaveholder and the foreman/supervisor at the Yard. For some this was the same person. For example, blacksmith striker, Tom's supervisor was Benjamin King, the master blacksmith and slaveholder. Luke Cannon worked for King and was rented out by slaveholder George Fenwick. Some slaves like William Allison were even owned by multiple slaveholders. Allison’s slaveholders were master shipwright James Owner, master joiner Thomas Lyndall and Clerk of the Yard Thomas Howard.38 Many slaves were able to use "two masters" to their own advantage by negotiating for more favorable conditions and independence.

38 Manumission and Emancipation Record, 1821-1862, Volume 1, p. 189-190, NARA RG21, Deed of Manumission re William Allison 12 April 1825.

One of the best descriptions of the predicament was written by Frederick Douglass. Douglass worked as a ship caulker in nearby Baltimore’s Fells Point Shipyard and left us a vivid account of his 1837-1838 experience:

There I was immediately set to calking, and very soon learned the art of using my mallet and irons. In the course of one year from the time I left Mr. Gardner's, I was able to command the highest wages given to the most experienced calkers. I was now of some importance to my master. I was bringing him from six to seven dollars per week. I sometimes brought him nine dollars per week: my wages were a dollar and a half a day. After learning how to calk, I sought my own employment, made my own contracts, and collected the money which I earned. My pathway became much more smooth than before; my condition was now much more comfortable. When I could get no calking to do, I did nothing. During these leisure times, those old notions about freedom would steal over me again. When in Mr. Gardner's employment, I was kept in such a perpetual whirl of excitement, I could think of nothing, scarcely, but my life; and in thinking of my life, I almost forgot my liberty. I have observed this in my experience of slavery,--that whenever my condition was improved, instead of its increasing my contentment, it only increased my desire to be free, and set me to thinking of plans to gain my freedom. 39

39 Douglass, Frederick, Autobiographies, ed. Henry Louis Gates Jr., New York: The Library of America: 1994. 83.

Working as a caulker aroused his deep resentment as his hard won wages went to an absent slaveholder:

I contracted for it, I earned it, it was paid to me, it was rightfully my own; yet upon each returning Saturday night I was compelled to deliver every cent of that money to Master Hugh. And why? Not because he earned it,--not because he had any hand in earning it,--not because I owed it to him,--nor because he possessed the slightest shadow of a right to it, but solely because he had the power to compel me to give it up. The right of the grim-visage pirate upon the high seas is exactly the same.40

40 Douglass p. 84.

Because of the profitable slave rental labor market in the District, slaveholders were willing to concede their bondsmen far greater freedom, especially those with lucrative skills like ship caulkers and blacksmiths, to "work their own time". "Working out" arrangements varied a great deal, but all allowed the master to earn a regular return with little or no outlay. The enslaved on the other hand, as Douglass notes, gave their master a fixed percentage of their wages. Typically the rented slave paid for their own food, clothing, and shelter. Purchasing oneself or family members was onerous, for the value of an adult was commonly equal to twelve to twenty months earning for a laborer.41 Again, Frederick Douglass provides the crucial details regarding the plight of slaves seeking work:

41 Whitman, T. Stephen The Price of Freedom Slavery and Manumission in Baltimore and National Maryland, University Press of Kentucky : Lexington, 1997, p. 123.

I was to be allowed all my time, to make all bargains for work, to find my own employment, and to collect my own wages; and in return for this liberty I was required, or obliged, to pay...three dollars at the end of each week, and to board and clothe myself, and buy my own calking tools. A failure in any of these particulars would put an end to my privilege. This was a hard bargain. The wear and tear of clothing, the losing and breaking of tools, and the expense of board made it necessary for me to earn at least six dollars per week to keep even with the world. All who are acquainted with caulking know how uncertain and irregular that employment is. It can be done to advantage only in dry weather, for it is useless to put wet oakum into a seam. Rain or shine, however work or no work, at the end of each week the money must be forthcoming.42

42 Douglas, p. 342-343.

Clearly slaveholders gained financially by having a cooperative and industrious bondsman. The enslaved in contrast could achieve a degree of leverage and independence and the potentiality of freedom. The requirements were that those purchasing their freedom first paid the slaveholder and after buying their essentials, put aside any money left over toward the purchase of freedom. From the slaveholder's perspective, entering into such agreements was doubly advantageous since the agreement secured a steady source of income for the slaveholder while it gave the worker hope of eventual freedom and therefore made the slave less likely to run away. These self-purchase agreements consisting of periodic payments to slaveholders provided some important security that their slave would complete the deal.

The majority of slaveholders negotiated their own rental contracts with the navy yard. From surviving documents we know some owners dealt directly with the master mechanics, especially those in the blacksmith shop, while others bargained with the Commandant or the Secretary of the Navy. Most slave rentals were private transactions and except for the notations of wages paid and the names of the slaveholder, we have few details. In some instances the enslaved conducted their own negotiations with an employer and arranged self-hire.43 Children were rented out as well. For instance, blacksmith striker Daniel Bell’s children were rented out by slaveholder Susannah Armistead for domestic work, including Bell’s two daughters Mary Ellen, age eleven, and Caroline, age nine.44

43 Martin Jonathan D. Divided Mastery: Slave Hiring in the American South (Boston: Harvard University Press 2004), 6-8. My comments regarding slave hire and rental are largely drawn from Martin’s insightful study of slave hiring in the South which is the first full-length treatment of this important topic.

44 Pacheco, p. 19-20. and NARA RG 21, Entry 115, O.S. Case file, 1832, Robert Armistead. "Inventory of slaves and other property belonging to the estate of Robert Armistead, Susannah Armistead, Administrator, 1838."

During the first three decades of the nineteenth century, the free black population of the District of Columbia grew. The racial composition of the District in the three decades since its founding had undergone rapid change as the number of free blacks dramatically increased from 783 in 1800 to 6,152 by 1830.45 One factor in this growth was the rise in the number of testamentary manumissions. In death, slaveholders frequently made extensive legal provisions for the distribution of all their property including their bondsmen. In 1803 Moore Fauntleroy, manumitted many of his slaves just prior to his death. Among those manumitted by Fauntleroy was Moses Liverpool. Liverpool moved into the District a year later to work at the Yard and provided a copy of his late master’s will to the Clerk of the District Court, as proof of emancipation:

45 Letitia W. Brown, Free Negroes in the District of Columbia 1790-1846 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1972), 11: 147.

At the request of Moses Liverpool, the following Will was recorded the thirteenth day of September Eighteen hundred & four. I, Moore Fauntleroy of the County of Richmond, do make this my last Will & Testament in the manner following. My soul I cheerfully resign to God in the hopes of pardon through our blessed Redeemer, my body to the earth to be interred at the direction of my friends & My Worldly Estate I give and bequeath as follows. In Primis It is my desire that my Just Debts be paid. Item: I give and bequeath to my brother Robert my Gold Watch. Item: I give and bequeath to my nephew Henry S. Turner all my Coat of Arms China - Item: I give & bequeath to the female children of the deceased Daniel Wilson each five pounds Cash to be paid out of my Estate. Item: I give and bequeath to the blind free Negro Billy Lewis forty shillings per annum during his life. Item: it is my desire that at the end of the year one thousand eight hundred and two, all my Negroes may have their freedom, if it can be affected. But if it cannot be, it is my desire that they be hired out in the county, not to be removed out against their Consent, & the money arising from their hires; the one half to be paid to them at the end of the year, in proportion as they hire … 46

46. Timothy Winn, District of Columbia Orphan's Court, Probate Court, 1836, Box 13. Spelling, punctuation and the use of ampersands is that of the original document. Purser Winn was related to Thomas Tingey by his marriage to Rebecca Dulany, a sister of Ann Dulany, Tingey’s second wife. 46 Liber L no 11 Folio 179 Archives of the District of Columbia, District of Columbia Deed Books.

Slaveholders' wills often provide detailed directions as to the disposition of their slaves. Timothy Winn, Naval Purser, in his 1836 will provided such instructions:

I give & bequeath to my Son my Servant Man Charles Grandison, & to my Daughter my Servant Woman Lizy, or Eliza Savoy. They are neither of them to be sold, nor be set free on any account whatever. I have too much regard for them to set them free to provide for & support themselves in their old age, after having had their faithful services for the best part of their lives. They must be comfortably & well provided for & kindly treated & supported & receive every indulgence compatible with their situation, & should either of my Children die, or by reason of any casualty or misfortune become incapable of providing for his or her Servant, the other Child must take such Servant & fully comply with all the requirements herein stated -

My Servant Man, John Douglass shall not be free, nor shall he be sold without his own free will & consent. He may be held in common by my Son & Daughter; or should one of them wish to own him, the other must pay such one half his estimated value. Should both wish to own him, my Executors John Coyle & William Speiden shall determine by Lot to which he shall belong, the fortunate one paying the other half his estimated value -

My Servants Betsy or Eliza Diggs & Juliette Tayloe, with her child, may either be sold, or be held in common by my Son and Daughter. If sold, the proceeds to be equally divided between them, but in no event shall either of them reside with, or in the family of my Daughter.4747 Timothy Winn, District of Columbia Orphan's Court, Probate Court, 1836, Box 13. Spelling, punctuation and the use of ampersands is that of the original document. Purser Winn was related to Thomas Tingey by his marriage to Rebecca Dulany, a sister of Ann Dulany, Tingey’s second wife.

Winn’s final instructions were typical of the conflict faced by many District slaveholders who sought to secure their bondsmen some measure of future good treatment, but left out any real provision for their freedom. This is particularly true in his treatment of Charles Grandison. Winn had rented Grandison to the Navy Yard for at least a decade, where he worked as an ordinary seaman.48

48 Muster of Ordinary 1815-1817, p. 17 -20 and Muster of Ordinary 1826, p.49-50, NARA RG 45 M125, Roll 163. Charles Grandison worked at least ten years as a slave in the ordinary, his pay going to Timothy Winn.

For Winn to free a slave by manumission was to reduce the total value of his estate. Even manumission by last will and testament was not always secure.

Robert and Aaron Clagett

There are over 200 known enslaved individuals who labored to build the White House and the Capitol Building. They were involved in every aspect of White House construction. They quarried stone, cut timber, made bricks, and assembled its roof and walls. They also worked as axe men, stone cutters, carpenters, brick makers, sawyers, and laborers throughout each stage of construction from 1792 through 1800. Local contractor and slaveholder, James Clagett, was one of the many slaveholders who profited from supplying enslaved labor to the construction of the White House. Clagett hired out “Negro George from July through September 1794 for five months and three days. He later hired out his enslaved laborers “Negro Davy “and Arron Clagett listed as “Negro Arron” for $1.40 per day, at the White House for the same wage as free white carpenters.

As work on the construction of the White House slowed, prominent slaveholders like James Clagett, George Clark, Samuel N. Smallwood and William B. Magruder began to supply their enslaved craftsman and laborers to the Washington Navy Yard. There slaveholders were once again, through their business and social contacts with Thomas Tingey and John Cassin, able to place their bondsmen on the steady and more lucrative federal payroll.Sources:

Mann, Lina,“Building the White House”, The White House Historical Association accessed 15 January 2023, https://www.whitehousehistory.org/building-the-white-house

Monthly Payroll for Carpenters and Joiners at the President s House, February 1795.National Archives, Records of the Commissioners of the City of Washington (Record Group 217)

Arnebeck, Bob, Slave Labor in the Capital: Building Washington’s Iconic Federal Landmarks, (Charleston, South Carolina: The History Press, 2014, p. 32.April 1808 WNY caulkers Robert and Arron Clagget enslaved to J. Clagget

(click link)Clagett died in 1834 and prior to his death he promised his two long service slaves, Aaron and Robert Clagett, their freedom. Aaron and Robert as young men to the Yard had worked with the ship caulkers. At Clagett’s death, his heirs challenged the will’s provisions to manumit the two brothers. Robert and Aaron petitioned the court to secure enactment of all the will’s provisions. The District Court found for the heirs and allowed them to block the manumission and retain the two brothers in bondage.49

49 Reports of Cases argued and determined in the Court of Appeals of Maryland Volume VIII (Baltimore: John B. Toy Printers 1839), 391-394 Negro John, and others vs. William Morton Administrator of James Clagett – December 1836.

That the said James Clagett, in and by the said paper writing, purporting to be his last will and testament, disposed of his estate, real and personal, and among other clauses was the following, to wit: "I give full power to my executors, and I direct them immediately after my decease, to manumit and release from slavery my two negro men, Robert and Aaron, to whom I hereby give the use and quiet possession, rent free, of my tenement and garden in Georgetown, late in the possession and occupancy of Mrs. Rabbitt, to hold and continue such use and possession for their joint lives, and the life of the survivor of them. I direct my executors, immediately after my decease, to manumit and release from slavery, after well-clothing them, my four negro women, Mary, Phoebe, Sophia, and Elizabeth, and all their increase, which increase shall be so specially manumitted as to belong to their mothers, the boys to the age of twenty-one years, and being girls to the age of sixteen years; and I declare, that all the said negroes may remain on my farm, and be supported out of my estate, they working thereon as usual, until the said farm shall be sold, and I direct my executors, when the said negroes shall depart from my farm in consequence of its being sold, to give and deliver unto Mary and Phoebe, in consideration of their numerous offspring, three barrels of corn, and one hundred pounds of meat, or a milch cow a-piece, at their option. I direct my executors, after making sale of my farm, whereon I reside, and after conveying and giving possession thereof to the purchaser thereof, without any delay, to manumit and release from slavery, (after well-clothing them,) all and every of my other slaves, except only my negro man, named Harry, a shoemaker, now in the service of Jesse Leach, which said Harry is to be taken as a part of the residue of my estate. My will and desire is, and I do hereby will and direct, that my male slaves shall be manumitted and discharged from slavery upon this condition, that they make comfortable and ample provision for old Phoebe during her life. It is understood and agreed, that nothing herein contained shall be taken to be an admission on the part of the defendant, that the said paper writing was executed by the said James Clagett, as his last will and testament, but only that such paper writing was exhibited for probate as aforesaid, and the same being now presented to this court by the petitioners."Most slaves in the District of Columbia were "slaves for life." However, a slave granted a prospective manumission became "a term slave."50 Slaveholder William Pumphrey’s will illustrates such a grant of future freedom. The will dated 12 August 1827 stipulated:

50 Rockman, Seth, Scraping by Wage Labor Slavery, and Survival in Early Baltimore, John Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, 2009, p. 66.

My slaves to be sold for a term of years this winter my debts to pay (to wit) Nell, aged about thirty seven to serve for the term of two years; Michael, aged about twenty-two to serve fifteen years; Thomas, aged about sixteen to serve twenty; Henry, aged about ten to serve twenty-six; Cornelia aged about eight to serve twenty-two; Waring aged about six to serve twenty-four years; Leath aged about four to serve twenty-four; Sharlotte aged about two years to serve twenty-six.

Among the enslaved designated to be sold for a term of years is "Michael", the diarist Michael Shiner then twenty-two years of age, "to serve fifteen years then manumitted."51 Shiner was purchased by Thomas Howard, from Pumphrey’s heirs on 8 September 1828. Howard as Clerk of the Yard knew Shiner prior to the sale. 52 In this important position he oversaw the keeping of all the Navy Yard muster, payroll records and work scheduling. This gave him ample opportunity to observe and assess a slave’s character and work record. At age twenty three and healthy, Shiner was in the prime of life and Howard, due to his unique position, ensured Shiner was steadily and profitably employed. In his 1832 will, Howard acknowledged his purchase of Shiner for a fixed number of years with his freedom at the end of the agreed period:

…having purchased a Negro Man named Michael Shiner for the term of fifteen years only, and having promised to manumit and set him free at the expiration of eight years, if he conducted himself worthy of such a privilege, it is my will and desire and I hereby set free and manumit the said Michael Shiner, at the expiration of Eight years from the date of said purchase.53

51 Last Will and Testament of William Pumphrey 12 August 1827 Prince George’s County, Md. Liber TT#1 folio 423. The 1820 U S Census; Census Place: District 3, Anne Arundel, Maryland; Page: 299; NARA Roll: M33-41; Image: 152 enumerates William Pumphrey’s household as 7 white persons and 13 enslaved individuals.

52 Maryland State Archives, Prince Georges County Register of Wills (Inventory), 1/25/9/8 p. 218, dated 8 September 1828.

53 Last Will and Testament of Thomas Howard., Archives of the District of Columbia District of Columbia Orphans Court (Probate) Court Records Group 2, Records of the Superior Court 1832 Box 11. The spelling, punctuation and the use of ampersands is that of the original document.

As one distinguished scholar notes: "such agreements were motivated by cold utility rather libertarian idealism."54

54 Ira Berlin Generations of Captivity, a History of African American Slaves. Cambridge Massachusetts: Harvard University, Belknap Press, 2003, p. 150.