by John G. M. Sharp

At USGenWeb Archives

Copyright All rights reserved

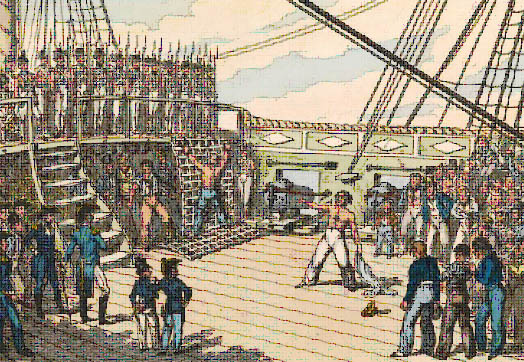

The Hero of the Trafalgar, lithograph Orford Smith, 1898

The morning of the 21st of October 1805 broke with light breezes and squally rain, but the alert lookouts on HMS Victory sighted the combined French and Spanish fleets, East South East about 5 or 6 miles off. This was a sight that many would never forget. In all they noted thirty-three enemy vessels spread out on the far horizon. William Roberson, a 20 year old volunteer Landsman on HMS Revenge wrote, first there was a sail on the horizon, than more, "for indeed they looked like a forest of mast rising from the ocean."1

1. W. Robinson, (Jack Nastyface), Nautical Economy or forecastle recollections of events during the last war (London 1836) pp. 13-14.

The Victory was about 21 miles (34 km) to the northwest of Cape Trafalgar, with the Franco-Spanish fleet between the British fleet and the Cape. About 6 a.m., Admiral Nelson gave the order to "prepare for battle". The crew cleared the decks for action, breaking away the captain and officer's cabins and sending all the timber below. Sawdust was spread over the decks to absorb the blood. In his cabin Admiral Lord Nelson, the son of a Norfolk rector, entered into his journal the following prayer:

"May the great God, whom I worship, grant to my country and for the benefit of Europe in general, a great and glorious victory and may no misconduct in anyone tarnish it; and may humanity after victory be the predominant feature in the British fleet. For myself individually, I commit my life to Him that made me; and may His blessing alight on my endeavors for serving my country faithfully. To Him, I resign myself and the just cause which is entrusted to me to defend. Amen."2

2. The National Archives Catalogue reference PROB 1/22 pages 26-7 (diary entry)

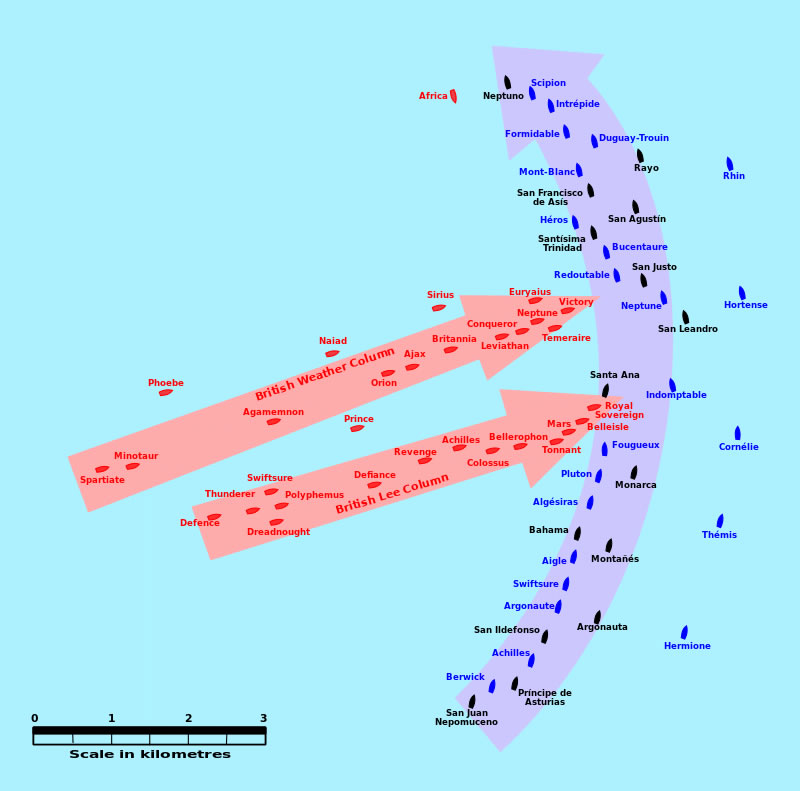

In the coming battle, Nelson knew the British fleet would be outnumbered and outgunned, the enemy totaling nearly 30,000 men and 2,568 guns to his 17,000 men and 2,148 guns. The Franco-Spanish fleet also had six more ships of the line, and so could more readily combine their fire. Nelson's solution to the problem was bold. Meeting with his captains in early October, he proposed to cut the opposing line in three. Approaching in two columns, sailing perpendicular to the enemy's line, one towards the center of the opposing line and one towards the trailing end, his ships would surround the middle third, and force them to fight to the end.3 Nelson hoped specifically to cut the line just in front of the French flagship, Bucentaure; the isolated ships in front of the break would not be able to see the flagship's signals, which he hoped would take them out of combat while they re-formed. He recognized the risks, but informed his captains, "Something must be left to chance; nothing is sure in a Sea Fight beyond all others. Shot will carry away the masts and yards of friends as well as foes; but I look with confidence to a Victory…"4

3. Best, Nicholas, Trafalgar, (London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2005), p. 182.

4. "Nelson's Trafalgar Memorandum", Victory off Cadiz, 9th October, 1805. British Library https://www.bl.uk/learning/timeline/item106127.html

Artist's conception of the situation at noon as Royal Sovereign

was breaking into the Franco-Spanish line5 (click to enlarge)5. See Wikipedia, "Battle of Trafalgar", this chart is public domain, "Pinpin" - own work, made with Inkscape from Image: Trafalgar 1200hr.gif: This drawing is based on an illustration in issue number 84 of the Strategy & Tactics magazine. The map was made by R. J. Hall using the Campaign Cartographer drawing program, and the image was reduced in size 50% in Paint Shop Pro. Ship icons are not to scale., CC BY-SA 3.0. https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=2852751

Below decks Victory’s doctor William Beatty who was born in Derry Ireland was also making preparations. As ship surgeon he had years of experience in naval medicine. He and his assistants the "loblolly" men all busied themselves that morning getting the medicine chest and bandages out. They also positioned sailcloth for the expected casualties to be placed, on that they might be dressed in rotation. Dr. Beatty’s instrument box was also laid out with care. His bone saw, amputation knives, bullet-removing forceps and a variety of others which he would later use to cauterize, or sear, human tissue.

The ship’s Gunner, the London born William Rivers, had served on HMS Victory since May 1790. At 50 years of age, his long years of experience made him in constant demand and would be put to the test this day. On Victory, Rivers was responsible for the ships armament and more than hundred weights of solid shot and two felt line magazines stuffed full with gun powder. From early morning Rivers and his mates made their final preparation to distribute powder, shot and weapons to the gun crews.

The "powder monkeys" the young boys whose hazardous duty was to run bags of gunpowder from the gun magazine to the ship's cannons were reminded to run nimbly less one stray spark ignite the volatile gun powder they held.

The French/Spanish were sailing in line off Cape Trafalgar, while the British came in from the west, gradually forming two lines.Naval records show Admiral Nelson’s flagship HMS Victory had 821 crew members serving including 23 Americans. The Victory muster enumerated 217 men pressed (involuntarily conscripted) into service. For much of the early republic American seamen had complained about being subject to involuntary and arbitrary conscription into the Royal Navy.6, 7. This article examines the careers of American seamen aboard the Victory as well the documentation for the lingering question regarding the number impressed or pressed American seafarers.

6. Sharp, John G. M., The "Tar and Feathers Company" Memorial (Petition) to Secretary of Navy, Robert Smith, from 72 Washington Navy Yard tradesmen, 10 November 1808 http://www.usgwarchives.net/va/portsmouth/shipyard/sharptoc/wny1808.html

7. Sharp, John G. M.., HM Dartmoor Prison and the War of 1812 http://www.usgwarchives.net/va/portsmouth/shipyard/sharptoc/shipyardstoc.html

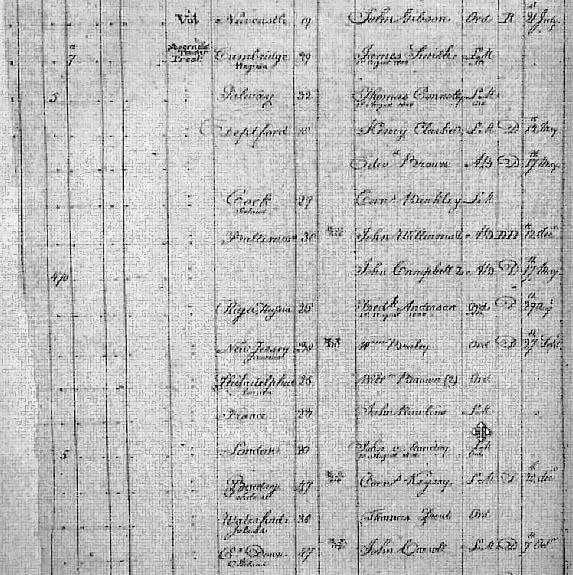

The list compiled below is that of American seamen who were recorded as present aboard HMS Victory during the Battle of Trafalgar.8 That is, those whose names and place of birth appear on the muster rolls between the dates of the 17 and 24 October 1805. By 1805 Royal Navy musters, were standardized records, employed by all ships and shore stations. Musters were primarily pay records; which listed the names of the crew serving on board a ship at a particular time and reflect data used to calculate their pay and related benefits. The 1805 naval muster form had 27 columns. For the sake of brevity and clarity, I have condensed the essential information into eight columns. These are: 1. Muster Number which was used by ship purser and his mates to record all subsequent information for a given sailor. 2. Name as entered on the Muster. 3. Home or Country. 4. Age, Rank or Trade. 5. Volunteer/Pressed. 7. Appearance on Board, and lastly, 8. Related Information.

8. The National Archives ADM 36, Ship: VICTORY. Trafalgar Ancestors https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/trafalgarancestors

Muster roll HMS Victory 1805, p.24, Three Americans,

# 464 James Smith, 472 Wm Braley, & 473 Wm Brown (2)

(click to enlarge)The crew of HMS Victory at the Battle of Trafalgar was multinational. Their place of birth is recorded as, 514 English, 67 Scots, 88 Irish, 30 Welsh, 23 Americans, 7 Dutch, 6 Swedes, 4 Italians, 4 Maltese, 3 Frenchmen, 3 Norwegians, 3 Germans, 3 Shetlanders, 2 Swiss, 2 Channel Islanders, 2 Portuguese, 2 Danes, 1 Russian, 1 African, 1 Manxman, 9 men from the West Indies and 48 Listed as "Unknown". There were 146 Royal Marines aboard the Victory, including a captain, three lieutenants, four sergeants, three corporals, a trumpeter and two drummers. They too would play a crucial role on 21 October 1805.

The crew for 21 Oct 1805, p. 21, were both and international and diverse. For example on a single page are listed number 291 George Ryan OS born Africa, number 292 Antonio Antoine, OS, St Nicholas, Cape Verde Islands, Number 302 William King, Baltimore Number 304 Charles Davis, AB, New York, Number 308 John Callaghan, OS, Bengal India. Plus two English seamen Number 295 Charles Davis (1), OS, London, Killed in Action and John Bowles, Deptford, LM, KIA.9

9. ADM 36/15900

Royal Navy muster forms required "Place and Country Where Born". However an exact number serving aboard HMS Victory from anyone country will ever be elusive and an ongoing subject of research. For example: the flagship’s 1805 muster gives Black seaman George Ryan, O.S., number 301, was born Africa. However, at the time of his medical discharge 21 October 1813, his place of birth is given as the island of Monserrat. Ryan appears to have been "'pressed" into service in Deptford.10 He is generally said to be the model for the Black seaman depicted on Nelson monument plinth in Trafalgar Square.11

10. ADM 35/2877 and ADM 35/3528)

11. Dodman, Dan," Throwing the Statue Book", https://www.dandodmanhistory.com/throwing-the-statue-book

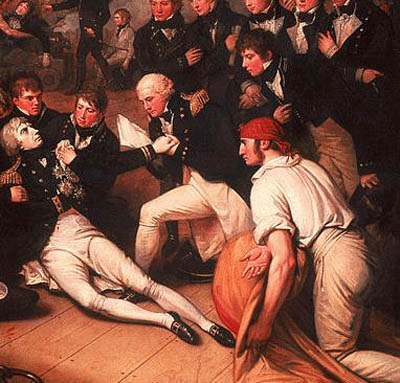

Another example from the HMS Victory muster, Midshipman Richard Bulkeley, number 677, birthplace was entered on the muster roll as "America" which in the modern era is still widely used as a synonym for the United States. However, this was not always so. A recent article in The Trafalgar Chronical by John R. Satterfield clarifies that Richard Bulkeley was born to a prominent family in 1784 in Halifax, Nova Scotia, then a British colony. The family had strong Canadian antecedents. His father, also a Richard Bulkeley, had joined the British Army and served in the Caribbean where he met a young post captain Horatio Nelson. There both men took part in the expedition to Nicaragua’s San Juan River. While the expedition was a failure, the two men became lifelong friends. Their friendship gave the younger Bulkeley an opportunity to write directly to Nelson in 1800. Nelson’s help advanced Richard’s prospects and later introduced him to captain Thomas Hardy. Richard first served in 1803 as Hardy’s aide-de-camp in HMS Amphion. Later he was a guest at Nelson’s table and favorite of Lady Emma Hamilton. His subsequent role at Trafalgar made the midshipman Bulkeley one of the last people to speak with Nelson. Nelson is recorded as whispering, "remember me to your father."12 In December 1798, HMS Vanguard carried King Ferdinand IV and the British ambassador Sir William Hamilton and his wife Emma from Naples to safety in Sicily. Captain Hardy did not altogether approve of Lady Hamilton. Once she tried to intervene on behalf of a boat's crew. Hardy had the crew flogged twice, once for the original offence and again for petitioning the lady.13

12. Scatterfield, John R., "Lieutenant Richard Bulkeley" The Trafalgar Chronicle, New Series 4, Journal of the 1805 Club, Peter Hore editor, (Seaforth Publishers, Great Britain, 2019), pp. 141-152.

13. Heathcote, Tony, Nelson's Trafalgar Captains and Their Battles (Leo Cooper Ltd, London, 2005), p. 80.

1805 Muster Roll HMS Victory, #301, George Ryan, O.S., born Africa

(open link to enlarge)In constructing the table below, I have utilized the original HMS Victory musters and logs as scanned and placed online by the British National Archives as Trafalgar Ancestors. This extensive database contains the names of 18,000 plus individuals who fought in the Battle of the Trafalgar on the side of the Royal Navy. In addition, I have compared these with the names and data listed in John D. Clarke’s superb "The Men of the HMS Victory at Trafalgar".14 Likewise, I have extensively used the 1805 Club‘s "Ashford Trafalgar Roll", which is nicely supplemented with additional data from medical records of those wounded or killed in action. Peter Goodwin’s concise and brilliant "HMS Victory Pocket Manual 1805: Admiral Nelson's Flagship at Trafalgar" has been my guide to both the flagship and its crew.

14. Clarke, John D. The Men of HMS Victory at Trafalgar including The Muster Roll, Casualties, Reward and Medals, Vintage Naval Library (Anthony Rowe, Eastborne, UK, 1999), Chapter 5 Patronage.

Dedication: To the Memory of Lt. Robert Douglas Sharp (1922–2002), USAAF, who loved the sea.

John G. M. Sharp 19 September 2023

Americans and the HMS Victory

During the Napoleonic Wars 1793-1814, each year several thousand men joined or were pressed into the Royal Navy. Most of American seamen enumerated on the Victory musters rolls designated Able Seamen, Ordinary Seamen or Landsmen, depended on their qualifications and previous experience. Historian John Keegan writes that in 1805 pressed men made up at least half of each ship’s crew.15 One estimate for the number of pressed men serving on HMS Victory during the battle is 217.16 Why the press? A warship like the Victory needed about ten times the crew of a merchant ship to man its guns.17

15. Keegan, John, The Price of Admiralty: Evolution of Naval War from Trafalgar to Midway (Penguin Books, London, 1990), p. 38.

16. Naval War College Museum Blog, The Battle of Trafalgar and the Naval War College Museum, 15 June 2020.

17. Lavery, Brian, Nelson’s Victory: 250 Years of War and Peace (Seaforth Publishing, Barnsley, UK, 2015), p. 165.

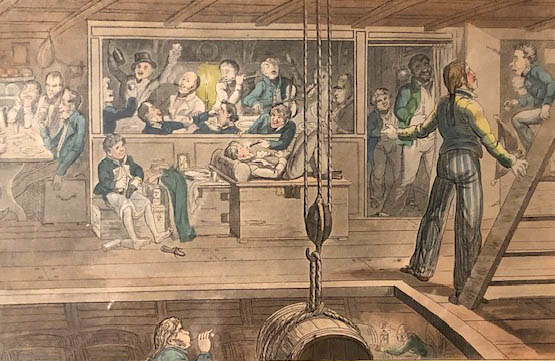

On board their new home recruits,volunteers and pressed men suddenly found themselves in a miniature mass society with hundreds of men toiling in unremitting twenty-four hour work cycles, under the constant supervision by their officers, their every activity standardized, closely coordinated and precisely defined by watch, station and maneuver. They also found "hierarchies were rigidly drawn and brutally enforced…"18

18. Frykman, Nicklas The Bloody Flag, Mutiny in the Age of Atlantic Revolution (University of California Press, Oakland, CA, 2020), p. 27.

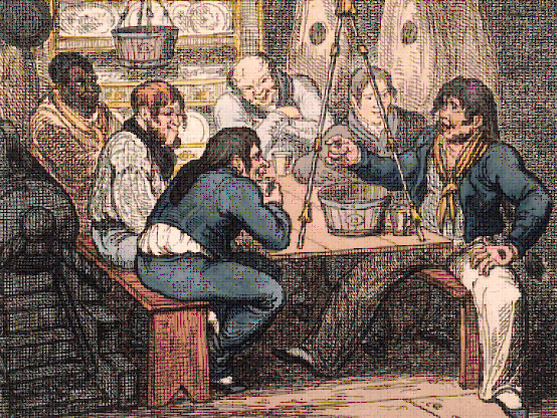

Mr. Blockhead finds things not as he expected

George Cruikshank, 1820, British MuseumSeagoing rates found in 1805 HMS Victory muster roll

Midshipmen like Richard Bulkeley were naval officers-in-training and received instruction in navigation and seamanship, plus other classes that would prepare them for a career. Although seamen were in short supply, there was never any trouble recruiting officers. A naval career offered the sons of wealthy landowning families seeking a chance for social advancement.19 Like most midshipmen, Bulkeley owed his appointment to important family connections.20 His father Richard Bulkeley, senior, had served together with Lord Nelson during the campaign in San Juan Nicaragua. He corresponded with both Admiral and Emma Hamilton.21 In a letter to Emma Lady Hamilton, dated 26 August 1803, Nelson wrote, "Bulkeley will be a most excellent sea officer."22 During the Battle of Trafalgar, Bulkeley was slightly wounded.23

19. Adkins, Roy, Nelson’s Trafalgar: The Battle That Changed the World (Penguin Books, London, 2005), p. 51.

20. White, Colin, editor. "Nelson - the New Letters (Boydell and Brewer, London, 2005) JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7722/j.ctt163tbgm, accessed 2 Sept. 2023

21. Coleman, Terry, The Nelson Touch: The Life and Legend of Horatio Nelson (Oxford University Press, London, 2002), p. 307.

22. The Dispatches and Letter of Vice Admiral Lord Nelson, editor Nicolas Harris, Volume 5, 1802-1804, (Henry Colburn Publisher, London, 1845) pp. 182-183 https://books.google.com/books?id=EEAJAAAAIAAJ&q=Bulkeley#v=snippet&q=Bulkeley&f=false

23. James William, A Naval History of Great Britain 1793-1820, volume IV, (Harding Lepard Company, London, 1826), p. 89.

Midshipman Richard Bulkeley on right leaning toward Admiral Nelson

From Benjamin West "Death of Nelson" 1806, Wikipedia Commons.Young Bulkeley served as aide-de-camp to the Victory’s Captain Thomas Hardy.24 Midshipmen were expected to have learned already, as able seamen and volunteers, to rig sails, keeping watch, relaying messages between decks, supervising gun batteries, commanding small boats, and taking command of a sub-division of the ship's company under the supervision of one of the lieutenants. He was one of the last people to speak with Admiral Nelson and attended the state funeral. Bulkeley is also depicted in Benjamin West 1806 large painting "The Death of Nelson". See detail above.25

24. Adkins, p. 194.

25. Scatterfield, John R., p. 149.

Quartermaster was a petty officer who assisted with numerous tasks on the quarterdeck, including attending to the ship binnacle (which housed the vessels compass), steering the ship, signaling and navigational duties.

Gunner’s mates like Thomas Bailey were warrant officers or senior petty officers. Among Bailey’s responsibilities was the maintenance of all of the ship’s great guns and small arms, the powder magazines (for which the Captain kept the keys – the gunner having to ask for them), and shot. Strict arrangements were laid down for the movement of powder, and all stores and supplies had to be minutely accounted for to the Board of Ordnance as opposed to the Navy Board (or Admiralty). At Trafalgar, Bailey was stationed close to Admiral Nelson, where he supervised the filling and issuing of cartridges to the guns. He would often be called upon for special jobs, like laying guns personally for the captain.Armourer, James Morrison was born in New York and 41 years of age when pressed into service in 1803. He was originally rated as an Able Seaman but speedily moved to the more important and higher paid armourer position. This rapid promotion to senior petty officer was likely based on his many years of prior naval experience. As the Victory's armourer, Morrison was responsible for the ship’s small arms, e.g. muskets, pistols, cutlass, pikes and axes. He would have a mate to assist him, including a gunsmith(s) in larger vessels – a First-Rater like Victory would carry c.400 muskets and pistols all told. The mates were petty officers, while the gunsmith was a species of very junior warrant officer. Morrison was also a highly skilled mechanic aboard: he had a forge and a set of special tools issued to him by the Ordnance Board.

Able Seaman, also Able-bodied seaman, abbreviated A.B. in British naval vessels was typically men considered the best seafarers with years of experience at sea and considered "well acquainted with his duty". The rating of A.B., is often found on ship's muster and payrolls: these two letters are frequently used as an epithet for the person so rated. He must be equal to all the duties required of a seaman in a ship--not only as regards the saying to "hand, reef, and steer," but also to strop a block, splice, knot, turn in rigging, raise a mouse on the main-stay, and be an example to the ordinary seamen and landsmen. Many former merchant sailors were rated as Ordinary Seaman, O.S., since they often lacked the requisite experience aboard a ship of war to rate A.B.

Ordinary Seaman, "O.S." Ordinary Seaman in the British Navy ranked above Landsman and below Able Seaman. An Ordinary Seaman who gained sufficient experience at sea and "knew the ropes", that is, knew the name and use of every line in the ship’s rigging could be promoted to A.B. An Ordinary Seaman’s duties aboard the Victory included"handling and splicing lines, and working aloft on the lower mast stages and yards.

Landsman abbreviated "LM." Landsman was the given to new recruits, novices with little or no experience at sea. Landsmen performed menial, unskilled work aboard ship. A Landsman who gained sufficient experience could be promoted to Ordinary Seaman.

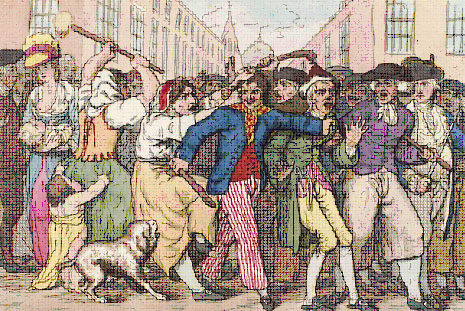

"The Sailors Description of Chase & Capture"

George Cruikshank, 1822, LOCHMS Victory Muster Roll, Boys 2nd Class, # B2/2, Cornelius Carroll, age 12

(open link)Boys were rated in three classes: Boys 3rd Class were under age 15 and paid £ 7 per annum. Boys 2nd Class were under age 18 and paid £ 8 per annum. Boys 1st Class were in training to become officers and paid £ 9 per annum. There are 34 Boys enumerated on the 1805 muster roll. In battle, young boys served as powder boy or powder monkey and manned naval artillery guns as a member of a warship's crew, primarily during the Age of Sail. Their chief role was to ferry gunpowder from the powder magazine in the ship's hold to the artillery pieces, either in bulk or as cartridges, to minimize the risk of fires and explosions. This function was usually fulfilled by boys 12 to 14 years of age. Powder monkeys were selected for the job for their speed and height: they were short and could move more easily in the limited space between decks and would also be hidden behind the ship's gunwale, keeping them from being shot by enemy ships' sharpshooters.26

26. Goodwin, Peter, Nelson's Victory: 101 Questions & Answers about HMS Victory, Nelson's Flagship at Trafalgar, 1805. (Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, Md., 2004) p. 50.

Boys were allowed half the usual ship’s allowance of rum and wine. He received pay for the half he did not draw. His ration allowed half-a-gill of rum and a quarter of a pint of wine a day. If a boy got drunk, or in any other way transgressed the rules of the navy, he was flogged, but with the boatswain’s cane instead of a cat of nine tails. In action, boys were stationed at a gun, with orders to supply that gun with cartridges from the magazine. In a hot engagement he was kept running to and fro, over the bloody and splinter-scattered deck, carrying the cartridges from the magazine.27

27. Masefield, John, Sea Life in Nelson’s Time (Methuen and Company, London, 1905), p. 112.

Two Boys who served the Victory guns were killed in action. They were Stephen Sabine, age 13, born Chelsea, London, and Colin Turner, age 16, born 1790, Paisley, Scotland. Surgeon's Log noted, Colin Turner was "shot through the abdomen and died of mortification shortly after the action." Sabine joined the Victory from the Marine Society.28 Both boys’ names are notated on the muster with "Killed in Action with the Combined Fleet 21 Oct 1805." The youngest Boy on the Victory that day was Thomas Twichett, age 12, born London. Twichett signed on as a volunteer Boy on 10 September 1805, just one month before the battle.29

28. The Ayshford Trafalgar Roll - CD - Extensive research by Pamela and Derek Ayshford, https://www.1805club.org/research-database/q/Sabine/area/men-at-trafalgar

29. Clarke, p. 48.

The Marine Society is often listed under the muster entries for Boys 1st and 2nd Class. The Society's stated aim was to support poor children from the age of 13 by giving them the skills needed to work on board the King’s ships.30 Found in 1763, the Society had recruited over 10,000 men and boys; in 1772, such was its perceived importance in the life of the nation, it was incorporated in an Act of Parliament. Admiral Nelson became a stalwart supporter and trustee of the charity, such that by the time of the Battle of Trafalgar (1805) at least 15% of British manpower was being supplied, trained and equipped by the Marine Society. The Marine Society avowed purpose:

that all stout lads and boys, who incline to go on board His Majesty’s Ships, with a view to learn the duty of a seaman, and are, upon examination, approved by the Marine Society, shall be handsomely clothed and provided with bedding, and their charges born down to the ports where His Majesty’s Ships lye, with all other proper encouragement.31

30. Marine Society, The National Archives, https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/education/resources/georgian-britain-age-modernity/marine-society/ accessed 3 September 2023.

31. Rodger, N. A. M., The Command of the Ocean: A Naval History of Britain 1649–1815 (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2004), p. 313.

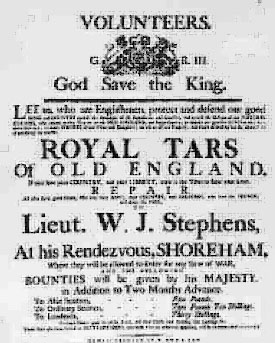

Volunteers and Pressed Men

The muster roll for the HMS Victory at battle of Trafalgar reflects four Americans voluntarily joined the Royal Navy. While muster books report any number of volunteers this is a misleading description of their status. We will probably never know exactly how many people were pressed, but even the most conservative estimated suggest that tens of thousands of men were forced in to the Navy against their will.31a However, it is now difficult to assess just how willing these men were, as press gangs made considerable effort to persuade them to "volunteer" in return for advances on pay or a promise of a bounty.32 For unemployed seamen, there was often little work on merchant vessels, their alternatives being charity, begging or the poor house. A few men were genuine volunteer’s motivated patriotism and opportunities for travel and adventure. Wartime bounties given to those who volunteered were small but welcome to many a poor sailor. At the beginning of war, the bounty money was £ 5 for Able Seamen, £ 2, for Ordinary Seamen and 30/ shillings for Landsmen. These rates increased as the war with France continued.

31a. Davy, James, Tempest: The Royal Navy and the Age of Revolutions (Yale University Press, New Haven, 2023), p. 37.

32. Adkins, p. 50.

‘Without a press, I have no idea how our Fleet can be manned." Horatio Nelson33

33. "Without a press, I have no idea how our Fleet can be manned." National Park Service, https://www.nps.gov/articles/impressment.htm

Half of the 23 Americans listed on the Victory muster roll for 21 October 1805 were pressed into the Royal Navy in May 1803. The Royal Navy wanted sailors with seagoing experience and as can be seen in our small sample all the Americans on Victory with exception of Landsman William Atkins had previous service in merchant or naval vessels. The Royal Navy used impressment extensively in British North America from 1775 to 1815. Its press gangs sparked resistance, riots, and political turmoil in seaports. Nevertheless, the Royal Navy extended the reach of its press gangs into coastal areas of British North America by the early 19th century.

A Press Gang in Operation,

"The Liberty of the Subject," James Gillray 1779John Davis of Abel (1774-1853) of New Castle Delaware, served in the merchant vessel Fidelity and in 1791 was with her in the port of Martinique where the Fidelity was surrounded by a British press gang. Davis and other American seamen were forcibly taken and conveyed to the HMS Ceres. There they were accused of being British citizens and told they were to be forcibly conscripted.

In the month of February 1797, I belonged to the Ship Fidelity, Captain Charles Weems, lying in the harbor of St. Pierre Martinique. About one o’clock Sunday morning, I was awakened by a noise on the deck, and going up, I found the ship in possession of a press gang. In a few minutes all hands were forced on board the Ceres frigate. We were ordered on the gun deck until day light by which time about 80 Americans were collected.

Soon after sunrise, the ship’s crew was ordered into the cabin to be overhauled. Each was questioned as to his name &c when I was called on for my place of birth and I answered "New Castle Delaware". The captain offered not to hear the last; but said "Aye, Newcastle well he’s a collier; the very man. I warrant him a sailor" "Send him down to the doctor" Upon which a petty officer – whom I recognized as one of the press gang made answer "Sir I know this fellow" "He is a schoolmate of mine and his name is Kelly. He was born in Belfast. Tom you know me well enough so don’t sham Yankee anymore"

The next was a Prussian who had come aboard in Hamburg as a carpenter of the Fidelity in September, 1796 – He offered when questioned not to understand English; but answered in Dutch. Upon which the captain laughed and said "this is no Yankee Send him down and let the quartermaster put in with the Dutchmen; they will understand him and the boatswain will learn him to talk English" He was accordingly kept. I was afterwards discharged by the order of Admiral Harvey on application of Mr. Craig, at that time American vice consul. I further observed that a full one-third of the crew were impressed Americans.3434. National Intelligencer (Washington D.C.) 12 October 1813, p. 3.

Impressment – the act of taking men into a Royal Navy by force with or without notice – was common practice in the 18th and early 19th century and effected families and communities. People liable to impressment were sailors; however, tradesmen with no connection to the sea were sometimes impressed, as in this 23 April 1791 petition of Mary Quick. Her petition gives us a rare glimpse of the emotional devastation and economic harm, press gangs brought on the family life of the poor and working class.35

35. The Petition of Mary Quick, wife of Michael Quick, 23 April 1791 (ADM 1/5119/16) British National Archives

That your Petitioner’s Husband is a Housekeeper a the Parish of St. Giles and by Trade a Coach Spring Maker, having wrought seven years at that Branch of Business with his Master Mr. Wildey, as it will appear by the annexed Certificate.

That her said Husband is no seaman, nor seafaring man, nor ever worked upon the water, nor in any business relating thereto.—

That notwithstanding thereof the said Michael Quick was impressed into His Majesty’s Sea Service, and now lies on board a Tender [boat, or larger ship used to transport men/supplies to and from shore or to another vessel] in the River—

That your Petitioner with two small children (and she is pregnant with a third) have no other support than the exertions of her said Husband, of which she is deprived by his detention as aforesaid, and which must soon bring her and them to ruin unless he is speedily released there from.

Your Petitioner therefore humbly prays that you will be pleased to grant her relief by giving such orders as may be the means of restoring the said Michael Quick to his distressed family and as in duty bound she will ever pray—

Signed by Janet Seton, for Mary Quick

No 26 Tower Street, Seven DialsBritish Law and Impressment

By British law, naval captains had the right to stop ships at sea, search for deserters and other British citizens, and force them to join the crews of warships. They were allowed to impress such Seamen, Seafaring men, and other persons described in the Press warrant sent herewith, as will not enter voluntarily and are not regularly protected, or hereafter excepted, provided they are able and fit for His Majesties service.36

36. Smithsonian National Museum of American History, Behring Center, Impressment, https://americanhistory.si.edu/on-the-water/maritime-nation/defending-independence/impressment

Black seaman William Godfrey in his 19 August 1799 letter to the Congress of the United States wrote about his being impressed into service into the HMS Mars. In doing so he related many impressed sailor’s dilemma. The problem being, that is, if an impressed seaman signed a Royal Navy vessel muster roll, he was no longer considered impressed but a volunteer. By signing, the muster impressed man made himself eligible for bounty and a share in any prize money. Godfrey writes,

Permit me to inform you that I am detained and obliged to serve on board of the Mars ship of War now lying at Plymouth, I was impressed by Sir Edward Pellew and treated very ill because I would enter with him. Neither I knowing myself to be an American as well for the reason I do not wish to serve them.37

37. Bolster, W. Jeffrey. "Letters by African American Sailors, 1799-1814." The William and Mary Quarterly, vol. 64, no. 1, 2007, pp. 167–82. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/4491606 accessed 7 Sept. 2023

Appeals

Between 1797 and 1810, more than 2,553 American seamen were freed from bondage. However, as Joshua Wolf points out, the entire process was drawn out and years could pass between an applicant submitting a petition and a decision. During the nineteen years of Anglo-American discord over impressment, 25 percent of appellants were granted their release from the Royal Navy. Another 2 percent deserted when the opportunity presented itself, 10 percent became casualties of war, and the Royal Navy retained nearly two-thirds of all seamen taken off American vessels.38

38. Wolf, Joshua, "The Misfortune to Get Pressed: The Impressment of American Seamen and the Ramifications on the United States, 1793-1812, Temple University, PHD dissertation 2013, p. 44, https://scholarshare.temple.edu/bitstream/handle/20.500.12613/4048/TETDEDXWolf-temple-0225E-12189.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

The muster roll of the HMS Victory provides the names of some of the lucky seamen 25 percent who successfully appealed their impressed status to the Admiralty Board. These are men who were able to depart the Victory prior to its departure from Portsmouth on September 14th 1805. Listed were Frederick Anderson, AB, number 471, born Riga, Russia released 29 August 1805 reason " being a foreigner " and number 479 Aron Anderson, AB, born Norway, released 4 September 1805 per Admiral Montague, reason "being a foreigner."

Americans David Bosworth, AB number 649, a pressed man, was released 4 September 1805 per order of Admiral Montague, reason "being an American" likewise Thomas Smith, (2) Yeoman of the Sheets, number 656, born Philadelphia, was released per order of Admiralty, 4 September 1805.39 The reason given was "being an American." 40 Two other Americans; Robert Morrice, O.S. number 669, born New York, age 42 and John Scott, O.S. born Philadelphia, age 53 were transferred in September 1805, to the British Naval Hospital in Malta and Gibraltar respectively.

39. The "Yeoman of the Sheets" was a petty officer, under the Boatswain, whose duty it was to see that fore or main sheets were properly stored. Burney, William, A New Universal Dictionary of the Marine: with a Vocabulary of French Sea Phrases and Terms of Art. (T. Cadell and W. Davies, London, 1815), pp. 63, 337.

40. Burney, p. 337.

Yet another avenue of appeal (for English sailors), caught up in the press was to plead, they were legally bound by indenture (contract) to serve a preexisting apprenticeship. In addition certain occupational groups were exempt by law. They were naval dockworkers and shipbuilders, merchant ship apprentices, pilots, seamen on outgoing trading vessels, and men given protections from the Admiralty or Parliament.41

41. Prendergast, Patrick M., "Forced Service: Official and Popular responses to the Impressment of Seamen into the Royal Navy, 1660-1815" PHD thesis, 2009, University of North Carolina, Wilmington, pp. 27, 70.

While no Americans qualified for this exemption, two English apprentices number 487, Ralph Coulson, O.S., age 20, born South Shields and number 541, Ralph Wake, O.S., age 20 born Northumberland were able to persuade the Admiralty, they were exempt and were subsequently released. Ralph Coulson was released on 4 Septembers 1805, by order Admiral Montague and Ralph Wake likewise on 11 September 1805.

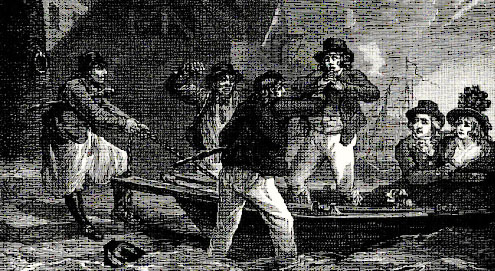

The Impress Service

A Press Gang seizing a London Waterman,

while a middle class couple looks onAs a part of Britain’s mobilization for war with France, the Admiralty Impress Service was dramatically expanded in various ports and key cities in Great Britain and Ireland. By 1795 the Service included 85 gangs, with 84 Lieutenants, 162 petty officers and 754 men and 32 captains, each with a district under his control. They were legally empowered to use the compulsion to recruit men for the Royal Navy. This was carried out by parties of seamen known as a "press gang "commanded by naval officers. This was based on the royal right to call all men for military service and later confirmed by many legal opinions. Impressment lasted until the end of the Napoleonic Wars because the administrative resources of the state could find no better way of providing men for the ships.42 After 1815, though not abolished, it was not used. Only seamen should have been pressed but in practice, as needs increased through the 18th century, all types of men were drawn in. Men impressed ashore were often taken to "pressing tenders", small hired vessels moored nearby. The "Sheerness Tender" and "Woolwich Tender" both noted in the 1805 muster roll, were each located near or beside the mouth of the River Medway and the outlet of the River Thames respectively.43 These tenders acted as floating prisons to safely confine those forcibly conscripted into naval service. There they were kept in locked compartments and under armed and careful guard.

42. Laverty, Brian, The Ships, Men and Organization 1793-1815 (Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD, 2003), pp. 120-121.

43. The Woolwich Tender operated as part of the Impress Service on the River Thames.

The Woolwich tender with impressed men, going down the river Tuesday at night, ran aground in Greenwich Reach. During the confusion which ensued, the men in the press room got on deck, and secured the vessel and making a raft, nine of them make for the shore. Alarm being given, a body of sailors and marines were sent from the Tarta frigate, and arrived as a second raft was let into the water; but the latter firing on the mutineers, they submitted and retired to the press room. Of the nine men who left the ship on the first raft, most are supposed to have been drowned.

The Bath Chronicle,8 December 1805 , thanks to Carole Carine.A Tender

Many of the American seamen aboard the HMS Victory were impressed and began their naval service locked in a tender in which they were conveyed them to their new home. William Robinson (1787-c.1836), a volunteer, age 20, born in Farnham, Surrey, served in the HMS Revenge at Trafalgar and left a vivid account of this, his first experience in the Royal Navy. 44

44. W. Robinson, (Jack Nastyface), Nautical Economy or forecastle recollections of events during the last war (London, 1836) pp. 25-26.

Whatever may be said about this boasted land of liberty, whenever a youth resorts to receiving ship for shelter and hospitality, he, from that moment, must take leave of the liberty to speak, or to act; he may think, but he must confine his thoughts to the hold of his mind, and never suffer them to escape the hatchway of utterance. On being sent on board the receiving ship, it was for the first time I began to repent of the rash step I had taken, but it was of no avail, submission to the events of fate was my only alternative, murmuring or remonstrating, I soon found, would be folly. After having been examined by the doctor, and reported seaworthy, I was ordered down to the hold, where I remained all night (May 1805) with my companions in wretchedness, and the rats running over us in numbers. When released, we were ordered into the admiral’s tender, which was to convey us to the Nore. Here we were called over by name, nearly two hundred, including a number of the Lord Mayor's Men, a term given to those who enter to relieve themselves from public charge

Upon getting on board this vessel, we were ordered down in the hold, and the gratings put over us; as well as a guard of marines placed round the hatchway, with their muskets loaded and fixed bayonets, as though we had been culprits of the first degree, or capital convicts. In this place we spent the day and following night huddled together, for there was not room to sit or stand separate: indeed, we were in a pitiable plight, for numbers of them were sea-sick, some retching, others were smoking, whilst many were so overcome by the stench, that they fainted for want of air. As soon as the officer on deck understood that the men below were overcome with foul air, he ordered the hatches to be taken off, when day-light broke in upon us; and a wretched appearance we cut, for scarcely any of us were free from filth and vermin.

William Robinson provides a glimpse of how he survived his horrible introduction to naval life. Like many new recruits he used both his will and determination and buried all feelings and emotions.

By this regular system of duty, I became inured to the roughness and hardships of a sailor’s life. I had made up my mind to be obedient, however irksome to my feelings, and our ship being on the Channel station, I soon began to pick up knowledge of seamanship.45

45. Robinson, p. 38.

After a tender was filled to capacity, it was sent to one of the major naval bases where the newly pressed men were placed on receiving ships commonly an older naval vessel and from there they were assigned to any vessel which had vacancies.46 The men were then transported to the HMS Victory a 104-gun first-rate ship of the line of the Royal Navy.

46. Laverty, pp. 122-123.

Four of the pressed men listed below came off the Sheerness Tender on the same day 11 May 1803 and one John Packett, off the Woolwich tender that same month. All this forced conscription and recruitment was part of Great Britain‘s step-up naval activity for war. The official declaration came on 18 May 1803, when His Majesty's government declared war on France on 18 May 1803. That same day Vice Admiral Lord Nelson hoisted his flag on the Victory.

At Trafalgar, Landsman William Robertson, born in Farmham Surrey 1785, was aboard the HMS Revenge and described the approach of the Spanish fleet and the opening shots as the Lord Collingwood’s flag ship HMS Royal Sovereign opened fire.47

47. Robinson, p. 46.

We now began to hear the enemy’s cannon opening on the Royal Sovereign, commanded by Lord Collingwood, who commenced the action; and, a signal being made by the admiral to some of our senior captains to break the enemy’s line at different points, it fell to our lot to cut off the five stern-most ships; and, while we were running down to them, of course, we were favored with several shots, and some of our men were wounded. Upon being thus pressed, many of our men thought it hard that the firing should be all on one side, and became impatient to return the compliment; but our captain had given orders not to fire until we got close in with them, so that all our shots might tell — indeed, these were his words: "‘We shall want all our shot when we get close in: never mind their firing: when I fire a carronade from the quarter-deck, that will be a signal for you to begin, and I know you will do your duty as Englishmen." In a few minutes the gun was fired, and our ship bore in and broke the line.

Americans who served on the HMS Victory in the Battle of Trafalgar 21 October 1805

Includes Name, Muster number, Home town or Country, Age, Rank or Trade, Volunteer or Pressed, Appearance on board and Related information. Some information is missing.

1. Richard Bulkeley, #677, America, age 18, Midshipman, Appears 31 July 1803. Midshipman Bulkeley was wounded in Action. For his "gallantry", he was promoted in 1806 to Lieutenant. Richard Bulkeley died 29 Dec 1809 while on duty in Port Royal, Jamaica.

2. Thomas Bailey, #588, America, age 32, Gunner's Mate, Pressed from Sheerness Tender, Appears 11 May 1803. Bailey took Admiral Nelson's last order at Trafalgar regarding the guns. Bailey was awarded prize money totaling, £10, 14s, 2d. In addition he was granted a Parliamentary award of £26, 6s.

3. James Morrison, #983, New York, America, age 39, was HMS Victory Armourer, Morrison was "Pressed" and his name first appears 11 May 1803. His original muster number was 448.

4. Richard Collins, #151, Philadelphia, born 1782, age 21, Able Seaman, Pressed, Appears 11 May 1803. Collins was pressed into the Service and joined the Victory from the Utrecht in May 1803. He was discharged to the Ocean in January 1806 and to the Scipion via the Salvador Del Mundo in October 1809 until November 1814. On Tuesday29 October 1805, HMS Victory Log recorded Captain Thomas Hardy, punished Richard Collins and five others with 36 lashes each for "Drunkenness".

5. Charles Davis, #304, born in New York, age 26, Able Seaman, Pressed, Appears 11 May 1803. He was pressed into the Service and joined the Victory from the Utrecht in May 1803. He was discharged to the Ocean in January 1806. He was discharged to the HMS Milford in June 1809 and was drowned in an accident at sea on 12 February 1810.

6. William Harvey, #817, America, age 29, Able Seaman, Volunteer, Appears 11 February 1804. He volunteered into the Victory from the HMS Kent in February 1804. He was discharged to the HMS Fame via the HMS Ocean in January 1806.

7. William Inwood, #730, an American was born in New York, America, age 27, Able Seaman. Inwood had come aboard the HMS Victory as a Boatswain Mate. As such his day to day job was to supervise and discipline crew members. Boatswain’s such as Inwood, were often called to correct or flog other errant crew members. Inwood nonetheless was quickly got himself into trouble and was punished by HMS Victory Captain Thomas M. Hardy with 48 Lashes for theft on 3 July 1804 (see punishments) and reduced to the rate of Able Seaman. In his time board the Victory Inwood had a troubled history having previously been disciplined with 48 Lashes for insolence in December 1803, and again the following May, when he received 12 Lashes for disobedience. William Inwood was discharged from Victory to the Ocean in January 1806 to the Salvador Del Mundo in July 1809 and the Armide in October 1809

8. John Jackson, #850, Philadelphia, age 27, Able Seaman, Appears 2 April 1804 from HMS Phoebe. Jackson joined HMS Victory 2 April 1804. He was discharged from Victory 24 December 1805 to HMS Ocean to 15 Jan 1806 and to HMS Fame 18 Jan 1806. He is recorded as having left that ship "Run" (AWOL) 20 July 1809 while it was at Palermo, Sicily. John Jackson is among those listed a 25 October 1805, list of "Impressed Seamen", published in the Aurora General Advertiser, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, by the Department of State. A similar notice regarding John Jackson and six other impressed American seamen was posted in the American Citizen on 26 July 1805 in New York City. The "48 lashes for awarded to Jackson for disobedience" may imply John Jackson had done something similar previously. See Samuel Leech recollections of witnessing four dozen lashes given to a sailor on the HMS Macedonian

9. Peter Jones, #841, Philadelphia, age 30, Able Seaman, Appears 2 April 1804. Peter Jones joined the HMS Victory from the HMS Phoebe in April 1804 and was discharged to the Fame via the Ocean in January 1806. He was discharged from the Service by Admiralty Order on 3 October 1814.

10. Samuel Lovett, #633, Portsmouth, America, age 42 born 1763, Able Seaman, Pressed, Appears 21 April 1803. Lovett was wounded in action 21 October 1805 by shot in the leg. Later Quarter-gunner. Lovett was discharged 2 June 1810 as "unserviceable" possibly as a result of wounds.

11. John Matthews, #905, New York, born 1780, age 25, Able Seaman, Volunteer, Appears 24 October 1804. Matthews volunteered into HMS Victory from the HMS Madras. He was discharged to the HMS Ocean in December 1805 and to HMS Fame in January 1806. He ran (Deserted) 17 August 1811 at Palermo, Sicily.

12. Alexander Murray, #818, America, age 24, Able Seaman, Volunteer, 11 February 1804. While in Portsmouth, 30 January 1810, Alexander Murray is recorded in the log as "Run", that is he deserted HMS Milford.

13. James Nipper #680, Rhode Island, America, age 21, Able Seaman, entered Royal Navy age 12, 1794, Appears 31 July 1803. Naval General Service Medal, with clasp Trafalgar, clasp for "Battle of the Glorious 1 June 1794" and clasp for action on 13 March 1806 HMS Amazon.

14. John Packett AKA Peter Fernie, Harve De Grace, Maryland, age 47, Able Seaman, Pressed from Woolwich Tender, appeared 13 May 1803. Discharged 29 July 1810, invalided.

15. James Smith, #464, Cambridge, Virginia, age 29, Able Seaman, Pressed from the Sheerness Tender. James Smith died 12 July 1814 aboard HMS Milford.

16. John Stair, #815, America, born 1778, age 27, Able Seaman, Volunteer, 11 February 1804. He volunteered into the Victory from the HMS Kent in February 1804 and was discharged to the Ocean in January 1806. He was discharged to the Rhin via the Salvador Del Mundo in August 1809. John Stair deserted on 18 Dec 1809 at Falmouth, England.

17. William Brown (2), #473, Philadelphia, born 1778, age 27, Ordinary Seaman, Pressed, from the Sheerness Tender. Brown was later promoted to Able Seaman. He was discharged from the Naval service 16 September 1814.

18. John Johnson, #110, Newport, Rhode Island, born 178, age 22, Ordinary Seaman, 11 May 1803. John Johnson joined the Victory from the HMS Utrecht in May 1803 and was discharged to the HMS Ocean in January 1806, and then the HMS Ville de Paris in April 1809. On 24 August 1805 HMS Victory log recorded Captain Thomas Hardy punished John Johnson, Cooks Mate, with 36 lashes for "Neglect of Duty and insolence."

19. William King, #302, Baltimore, age 20, Ordinary Seaman. He was taken by a press gang and sent 11 May 1803 to HMS Victory. King was discharged 15 January 1806 to HMS Ocean. His prize money totaled: £1, 17s, 8d, Parliamentary Award £4, 12s and 6d.

20. John Lewis (1), #416, Baltimore, age 27, Ordinary Seaman, Pressed, Appears 11 May 1803. John Lewis joined HMS Victory from HMS Utrecht. John Lewis was discharged 15 January 1806 to HMS Ocean. Lewis’s prize money totaled: £1, 17s, 8d, Parliamentary Award £4, 12s and 6d.

21. William Sweet, #890, New York, born 1784, age 20, Ordinary Seaman, Pressed, appears 1 January 1803. Sweet joined the Victory from the HMS Termagant in January 1804. He was discharged to the HMS Ocean in January 1806. Later Sweet joined the HMS Milford in July 1809 and was discharged to the HMS Prince Frederick in August 1814. Sweet was discharged from the service 16 September 1814.

22. William Thompson (1), #141, Philadelphia, born 1775, age 28, Ordinary Seaman, Volunteer, Appears 11, May 1803. Thompson joined the HMS Victory from the HMS Utrecht in May 1803. Thompson was discharged to the HMS Ocean in January 1806. Later he was discharged to the HMS Rhin via the HMS Salvador Del Mundo in August 1809.

23. William Atkins, #550, Charlestown, born 1780, age 25, Landsman, Pressed from the Sheerness Tender, Appears 11 May 1803. William Atkins was discharged to the HMS Ocean in January 1806, and immediately to HMS Fame. Akins was discharged to the HMS Conquistador in March 1811 until joining the HMS Salvador Del Mundo in July 1813. Atkins continued to remain a Landsman in the Royal Navy until 1813.

Life aboard the HMS Victory, 1805

Get "me clear of this miserable situation"

Benjamin Stevenson pleads with his brother-in-law to help him leave the ship.

Benjamin Stevenson, number SB 395, was pressed and afterward deposited by the Woolwich Tender on 11 May 1803 aboard HMS Victory. Stevenson had considerable prior naval experience and was immediately rated quartermaster. The duties of a quartermaster comprised steering the ship, stowing ballast, placing provisions in the hold, keeping time using the ship's watch-glasses and overseeing the delivery of provisions to the purser's steward. Stevenson must have had considerable prior experience as quartermasters were usually older seamen.

Spithead 18 August 1805

Dear Brother,

. . . We have once more arrived in England and I once more beg your friendship of getting me clear of this miserable situation, if any means it lies in your power which I trust god is. For this one of the most miserable lives that ever a man led. Brother I hope that you will be so kind as do all that lies in your power to get me clear. I think it will be one of the greatest favors that ever were bestowed upon man. There has been several got clear from this ship when we in the Straights for two substitutes and got them for £ 40 and I think if you can get two for twice as much I would not begrudge the money to get clear of this prison, if you can get any substitutes I hope you will be so kind as to speak with Mr. Hawks and see if he can do this for me. Brother if you can get me clear by any means I hope you will and if you think it impossible I hope you will be so kind as to write with all possible haste . . 48

48. Letters of Seamen in the Wars with France, 1793-1815, editors Helen Watt and Anne Hawkins (Boydell Press: London, 2016), pp. 227.

Discipline

Strict discipline in the HMS Victory was enforced by the Boatswain and his mates. Typical infractions and crimes included theft, insubordination and neglect of duty, drunkenness, fighting, or general uncleanliness. When reading these early accounts of punishments, it’s important to keep in mind, any officer or petty officer could put a sailor on report. Those accused of some nebulous infraction like "contempt" or "insubordination" had little or no opportunity to present evidence to the contrary. For an enlisted man to question the veracity of the statement of his superior typically increased the likelihood of his being awarded a greater number of lashes.

For most of these offenses flogging with the cat of nine tails was standard. The number of lashes generally awarded varied. The "Cat" was applied by the master at arms in front of the whole ships company. From the surviving logs of the Victory for the years 1804-1805, this usually occurred at least once a week typically on Tuesday or Saturday. Flogging was always witnessed by the entire ship's company. This regular ritual of punishment and pain was meant to serve as an example and to intimidate all those assembled or within ear shot. The sentence would be read out loud. The culprit would be stripped to the waist, tied to a wooden grating and given as many as thirty-six lashes. Marines always lined the deck with loaded musket and fixed bayonets to prevent insurrection. The cat of nine tails was then taken out of the bag and the punishment would begin.

Captain Thomas Masterman Hardy as commanding officer of the flagship proved himself a strict disciplinarian. While his predecessor Captain Samuel Sutton had imposed punishments relatively sparingly of 12 lashes (the regulation amount) as the norm and 24 lashes for more serious offenses, Hardy who particularly loathed drunkenness made 36 lashes, the new norm. For two years in the Mediterranean (1803-1805) with Thomas Masterman Hardy as flag captain, no ship punished its crew more frequently or severely than the Victory49

49. Knight, p. 550.

Man Overboard!

IMAGE: HMS Victory log, Wednesday, 12 September 1804

Moderate Breezes and hazy, shifted the main sails, at 9 tacked at 9.55 James Archibald, Seaman fell overboard, downed Cutter and got him safe in, being saved by Mr. Edward Flin masters mate, jumping overboard after him. AM moderate and clear, Punished Daniel Reed, Seaman 48 lashes for drunkenness, Henry Cary, Thomas Service, Seamen 36 lashes each for drunkenness. William Honor, Seaman, 24 lashes, for contempt, William Fleming, Seaman, 12 lashes, for uncleanliness, John Jacobs, 60 lashes for fighting and contempt.Swimming and Rescue

In the early ninetieth century, most British seamen did not swim; swimming was not a considered a recreational sport. Working aloft or trimming sails was always dangerous as just one single misjudged step could send a man crashing to the deck or over the side.

The great majority of sailors like the unfortunate James Archibald (born London) came from urban areas and could not swim. In any case normally the odds of rescue were slim to none at all. If he could swim (most could not) and if the water wasn’t so cold as to paralyze him, it could still take a half hour or so before the ship could stop and launch a boat. A floating sailor in anything more than a flat calm was and is very hard to spot. Imagine trying to see a man bobbing about in a seaway a mile or two away. At night, in wind and rain with only a dim oil or candle lantern for illumination many a poor sailor was lost. See HMS Victory, log entry, 21 September 1805, with notation Robert Chandler, Seaman, fell overboard and was lost at seaReverend A.J. Scott HMS Victory Chaplain, regarding Vice Admiral Nelson, 12 September 1804

One bright morning, when the ship was moving about four knots and hour through a very smooth sea, everything on board being orderly and quiet, there was a sudden cry of "a man overboard" A midshipman named Flinn, a good draughtsman, who had been sitting on deck comfortably sketching, started at the cry, and looking over the side of the ship, saw his own servant, [James Archibald] who was not swimmer, floundering in the sea. Before Flinn could get his jacket off, a captain of the marines had thrown the man a chair through the port hold in the wardroom to keep him floating and in the next instant Flinn had flung himself overboard and was swimming to the rescue. The Admiral [Nelson] having witnessed the whole affair from the quarterdeck was highly delighted with the scene and the party, the chair and all had been hauled on deck he called Mr. Flinn, praised his conduct and made him a Lieutenant on the spot. A loud huzza from the midshipmen, whom the incident had collected on deck and were throwing their hats in the air in honor of Flinn’s good fortune, arrested Lord Nelson’s attention. There was something significant in the tone of their cheer which he immediately recognized and putting his hands up for silence and leaning over the crowd of middies, he said with a good-natured smile on his face, "Stop young gentlemen! Mr. Flinn has done a gallant thing today and he has done many gallant things before - for which he has gotten his reward, but mind! I’ll have no more making Lieutenants for servants falling overboard"

Source: Scott, Alexander John, The Life of the Rev. A.J. Scott, D.D. Lord Nelson’s Chaplain, (Saunders and Otley, London, 1842),,pp.125 -126, https://books.google.com/books?id=sib3xG-nGL8C&q=flinn#v=snippet&q=flinn&f=false

After pronouncing Flin’s promotion to Lieutenant, Admiral Nelson quickly penned a note to the Admiralty confirming the heroic rescue and promotion.

Admiral Horatio Nelson to the Admiralty 12 September 1804

Victory at Sea, 12th, September 1804

Sir,

I herewith transmit you for the information of the Lords Commissioners of the Admiralty, a copy of a Survey held on Lieutenants Thomas Vol, of his Majesty’s Ship Niger and request you will be pleased to acquaint their Lordships that I have removed Lieutenant Nicholas (at his own request) to the Niger, and have appointed Mr. Edward Flin, of the Victory, to act in the interim, in consequence thereof; a copy of whose Acting–Order is also herewith transmitted. I must beg to observe that Mr. Flin’s conduct very justly merits my approbation as stated in the margin of the said Acting-Order, and that his general conduct since he has been with the Victory, has been very meritorious. I therefor hope their Lordships will approve my placing him in this invaliding vacancy, and confirm the appointment. I am, &c.

[Signed] Nelson and BronteLord Nelson, in a marginal note to the Admiralty, explained, Mr."Flin had jumped overboard on the night of the 11th instant, then very dark, and at the risk of his own life, saved James Archibald, a Seaman belonging to the Victory, who had fallen overboard and certainly would have drown."

The daring rescue and Admiral Nelson’s on the spot promotion, jumpstarted Edward Flin’s career. Edward Flin at his death in May 1819 had risen to be a post captain and a companion of the Order of the Bath.

James Archibald after his fortuitous rescue continued to serve on HMS Victory and was present at the Battle of Trafalgar. Later that same year, on 3 December 1805, Captain Hardy sentenced Archibald, to 36 Lashes, for "Quarrelling and Fighting" Archibald like many a seamen may have had problems with alcohol. The British Navy in 1804 issued two serving of grog (diluted rum) per sailor, each day. Not surprisingly drunkenness was the most common infraction for which sailors received 36 Lashes.

Despite his suffering the lash, James Archibald chose to remain in the Navy, and served as a carpenter’s mate on various other ships until he was discharged 3 October 1814 from service per Admiralty order.Source: The Dispatches and Letter of Vice Admiral Lord Viscount Nelson, Volume 6, May 1804 – to July 1805, Editor, Nicholas Harris Nicolas, (Henry Colburn, London, 1846), pp. 198-199.

Appendix: Punishments given out by Captain Thomas Masterman Hardy in HMS Victory

Officially no British Navy captain could award more than 24 lashes without seeking higher authority, which required a court martial. Many captains, however, did go well beyond 24 lashes on a regular basis: one such was Captain Thomas Masterman Hardy, commanding officer of HMS Victory. The following reflects the punishments awarded by Captain Hardy from 13 August 1805 to 3 December 1805 as recorded in the captain’s log.* The names of individual seamen and marines, their place of birth, and age were compared with HMS Victory muster and payrolls.**

* ADM 51/4514/3, Part 3: HMS Victory 1 August 1805-15 January 1806 captains log, by Thomas Masterman Hardy, Captain

** ADM 36/15900 HMS Victory muster and payroll

"A Point of Honor" a Flogging, by George Cruikshank 1825,

Royal Museum, GreenwichDuring the period 1790-1820, flogging in the British Navy on average consisted of 19.5 lashes per man.*** Captain Thomas Masterman Hardy, was "a renown flogger" on average, he awarded 36 lashes per man. As commanding officer of the flagship HMS Victory, he maintained a regime of strict discipline.**** He particularly loathed drunkenness and his punishments were severe. For example: on 19 October 1805, Hardy had 10 seamen flogged for drunkenness; each man was given 36 lashes. This was two days before the Battle of Trafalgar.*****

*** Underwood, Patrick, et al. "Threat, Deterrence, and Penal Severity: An Analysis of Flogging in the Royal Navy, 1740-1820." Social Science History, vol. 42, no. 3, 2018, pp. 411–39, JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/90024188 Accessed 15 Oct. 2023

**** Goodwin, Peter, HMS Victory Pocket Manual 1805: Admiral Nelson's Flagship At Trafalgar (Opsrey Publishing, London, 2018), pp. 58-59.

*****Hounslow E. J. Nelson’s Right Hand Man: The Life and Times of Vice Admiral Thomas Freemantle(The History Press, Gloucestershire, 2016), Kindle, Location 2942.

Typical infractions and crimes that were punished aboard the Victory included theft, insubordination and neglect of duty, drunkenness, fighting, or general uncleanliness. For most of these offenses flogging with the cat of nine tails was standard. In the list below, "drunkenness" is most commonly mentioned. The twice daily rum rations (authorized in longstanding Admiralty regulations) which the crew received served to exacerbate misconduct and disciplinary problems.

The number of lashes generally awarded varied. The "Cat" was applied by the master at arms in front of the whole ships company. From the surviving logs of the Victory for the years 1804-1805, this usually occurred once a week typically on Tuesday or Saturday. Flogging was always witnessed by the entire ship's company, as an example to others. The sentence would be read out loud. The culprit would be stripped to the waist, tied to a wooden grating and given as many as thirty six lashes. Marines always lined the deck with loaded musket and fixed bayonets to prevent insurrection.

Samuel Leech (1798 -1848) who served on HMS Macedonian as a young sailor, described one such flogging.

The boatswain’s mate is ready, with his coat off and whip in hand. The captain gives the word. Carefully spreading the cords with the fingers of his left hand, the executioner throws the cat over his right shoulder; it is brought down upon the now uncovered herculean shoulders of the man. His flesh creeps - it reddens as if blushing at the indignity; the suffer groans; lash follows lash until the first mate, wearied with the cruel employment gives place to a second. Now two dozens of these dreadful lashes have been inflicted: the lacerated back looks inhuman; it resembles roasted meat burnt nearly black before a scorching fire… The executioner keeps on. Four dozen strokes have cut up his flesh and robbed him of all self-respect: there he hangs, a pitied self-despised, groaning bleeding wretch; and now the captain cries forbear! His shirt is thrown over his shoulders; staining his path with red drops of blood and the hands "piped down" by the Boatswain sullenly return to their duties.*****

***** Samuel Leech, A Voice from the Main Deck: Being a Record of the Thirty Years' Adventures of Samuel Leech (Tappan, Whittemore and Mason, Boston, 1843), pp. 50-51.

Punishments Given Out by Captain Thomas Masterman Hardy, HMS Victory

Name, Rate, Offense, Number of Lashes, Place of birth, Age

Friday, 5 August 1803,

Punished Peter Blumberry, Seaman, Drunkenness, 36 Lashes.Tuesday, 18 August 1803

Punished Cornelius Sullivan, Marine, Disobedience of orders, 12 Lashes.Monday, 22 August 1803,

Punished, John Parnell, Marine, Drunkenness, 36 Lashes.Tuesday, 30 August 1803,

Punished, John Cross, Seaman, Drunkenness, 36 Lashes

Timothy, Buckley, Marine, Drunkenness, 24 Lashes

Thomas Marsden, Marine, Drunkenness, 24 Lashes.Monday, 7 November 1803

IMAGE: Flogging Around the Fleet (Click to enalrge)

"Came alongside towed by the Boats of the Fleet, Robert Dowyer, Private, Marine, of HMS Bellesiste & Received 42 Lashes for mutinous expressions and being punished by Court Martial ."

The fleet boats than proceed to the next ship, where they accorded Pvt. Dowyer, the same punishment until every ship had given him a similar amount. The total number of Lashes varied, but 260 was typical.Tuesday, 3 July 1804

William Inwood, Boatswain Mate, Theft, 48 Lashes, New York, America, age 29

Anthony Antonio, Cooks Mate, Disobedience of Orders, 36 Lashes, St. Nicholas, age 25

Thomas Palmer, Seaman, Drunkenness, 36 Lashes, Surrey, age 20

John Thomas2, Seaman, Insolence & Disobedience of orders, 24 Lashes, London, age 24

John Brice, Marine, Neglect of Duty, 12 Lashes, Not listed, Not listed

Daniel Sweeny, Marine, Contempt & Drunkenness, 36 Lashes, Not listed, Not listedSaturday 4 August 1804, p.30

John Brown, Seaman, Drunkenness, 13 Lashes, John Hind, Seaman, Drunkenness, 36 Lashes, Simon Moon, Seaman, Drunkenness, 36 Lashes, William Cobourne, Marine, Drunkenness, 36 Lashes, Edward Flynn, Marine, Drunkenness, 36 Lashes, John Wells Seaman, Disobedience of Orders and Neglect of DutyTuesday 14 August 1804, p.31

William Smith (1) Seaman, Drunkenness 36 Lashes, James Connor, Seaman , Drunkenness, 36 Lashes, Edward Gallant, Seaman, James Norgrove, Marine Drunkenness 36 Lashes, Joseph Hines, Marine, Drunkenness, 48 Lashes, Thomas Wilson, Marine, Drunkenness, 48 Lashes, James Wilton, Marine, Drunkenness, 48 Lashes,, John Parnell, Marine, Drunkenness, 48 Lashes, John Hood, Marine, Drunkenness, 48 Lashes, William Taft, Marine, , Sleeping at his Post, 24 Lashes, Richard Crofts, Marine, , Sleeping at his Post, 24 Lashes, David Powell, Marine Contempt, 12 Lashes , William Butler, Seaman, Disobedience of Orders, 12 Lashes, William Patterson, Seaman, Contempt and Disobedience of Orders. 24 LashesWednesday 15 August 1804, p.31

James Hartnell, Seaman, Drunkenness, 36 Lashes, William Thompson, Seaman, Drunkenness, 36 Lashes, John Corran, Seaman, Drunkenness, 36 Lashes, John Kidd, Seaman, Drunkenness, 36 Lashes, William Cooke, Marine, Disobedience of Orders, 12 Lashes, Joseph Murray, Seaman, Disobedience of Orders, 12 Lashes, William James, Seaman, Disobedience of Orders, 12 Lashes, William Pritchard, Seaman, Disobedience of Orders, 12 Lashes, John Jacobs, Seaman, Disobedience of Orders, 12 LashesThursday 16 August 1804,p. 31

"Punished two Seamen and one Marine with 36 Lashes each for Drunkenness" Occasionally as in this instance, the log does not provide namesTuesday 21 August 1804, p.32

Punished John Kennedy, Seaman, 60 Lashes for Striking his Superior Officer, Henry Stiles, Seaman, 48 Lashes for Drunkenness, Robert Chandler, Seaman, 24 Lashes, James Chapman, Seaman, 36 Lashes, John Morgan, Marine and Stromble Pelligrue, Seamen with 12 Lashes each for Disobedience of Orders.Monday, 29 August 1804,p.32

Punished James Jones, Seaman, John Brown Seaman with 36 Lashes each for Drunkenness. Peter Legg, Seaman 24 Lashes for Fighting, William Morris, Seaman, 24 Lashes for Neglect of Duty, William Beeton, Marine, 24 Lashes for Sleeping on Post.Saturday, 13 Oct. 1804, p.33

John Smith (2), Seaman, Drunkenness, 36 Lashes, age 30 and born in London. John Smith (2) a volunteer, wounded in action at Trafalgar. William Cable, Seaman, Drunkenness, 36 Lashes. John Howard, Seaman, Drunkenness, 36 Lashes, age 21, and born County Mayo, Ireland. Christopher Dixon, Seaman, Drunkenness, 36 Lashes, age 29, born South Shields, Durham, pressed. William Gibbons, Seaman, Drunkenness, 36 Lashes, age 30, born London, pressed. Henry Butcher, Seaman, received 60 Lashes for theft, age 24, born Shields, England, pressed. On 25 January 1807, while serving HMS Fame, Butcher fell overboard and drowns.Thursday, 17 Oct. 1804, p.33

Angus McDonald, Seaman, Drunkenness, 36 Lashes, age 36. Mc Donald was born Inverness, Scotland. McDonald was later wounded in action at Trafalgar. John Sewish , Seaman, Drunkenness, 36 Lashes, Robert Pritchard, Seaman, Drunkenness 36 Lashes, age 21, Carnarvon, Wales, Volunteer, Jeremiah Sullivan, Seaman, Drunkenness, 36 Lashes, age 33, Cork Ireland, Thomas Wood (2), Seaman, Drunkenness, 36 Lashes, age 40, Washington, County Durham, Pressed , Charles Boyd, Seaman, Drunkenness, 36 Lashes, William King, Seaman, Drunkenness, 36 Lashes , age 18, born Baltimore, America., John Wilson, Seaman, Drunkenness, 48 Lashes.Saturday 3 August 1805, p.182

Robert Norville, Seaman, Drunkenness, 36 Lashes, Plymouth, Devon, age 22

Samuel Cooper, Seaman Drunkenness, 36 Lashes, Bury, Lancashire, age 36

John Welsh, Seaman, Drunkenness 36 Lashes, Waterford, Ireland, age 28

James Mc Laughlin, Seaman, Drunkenness, 36 Lashes, Roscommon, Ireland, age 26

Thomas Hawkins, Marine, Neglect of Duty, 36 Lashes, Asbrittle, Somers age 25

Cornelius Sullivan, Marine, Neglect of Duty, 36 Lashes, Cork, Ireland, age 28Tuesday, 13 August 1805, p. 183

Alexander Warden, Seaman, Drunkenness, 36 Lashes, Plymouth, age 26

Peter Hall, Seaman, Drunkenness, 36 Lashes, London, age 20

John Dutton, Marine, Drunkenness, 36 Lashes, Cheadle, age 28

John Thomas2, Seaman, Contempt, 24 Lashes, London, age 24

John South, Marine, Contempt, 24 Lashes, Kiddeminster, age 22

James Johnson, Marine, Neglect of Duty, 24 Lashes, Newry, age 22Saturday, 24 August 1805, p. 184

John Thomas2, Seaman, Drunkenness, 36 Lashes, London, age 24

John Kennedy2, Seaman, Quarrelling & Contempt, 36 Lashes, Dublin, age 24

Christopher Dixon, Quartermaster, Quarrelling & Contempt, 36 Lashes, South Shields, age 27

John Johnson, Cooks Mate, Neglect of Duty and insolence, 36 Lashes, Newport, Rhode Island, age22

William Perry, Marine, Insolence, 24Lashes, Dublin, age 24Tuesday, 10 September 1805, p. 186

John Thomas, Seaman, Theft, 36 Lashes, London, age 24

Richard Powell, Seaman, Contempt, 24 Lashes, Cheswick, age 24

Henry Butcher, Seaman, Neglect of Duty and Disobedience, 24 Lashes, Shields, age 24

John Jacobs, Seaman, Neglect of Duty and Disobedience, 24 Lashes, Arundel, age 25

Robert Faircloth, Seaman, Neglect of Duty and Disobedience, 24 Lashes, Norfolk, age 22

James Long, Drummer, Marine, Neglect of Duty and Disobedience, 12 Lashes, Not listed, age 19Saturday, 21 September 1805, p. 188 "At 7.20 fell overboard Robert Chandler, Seaman, (link)

Backed the main top sail & sent a boat to look for him but could not find him."Tuesday 24 September 1805, p. 189.

John Moore, Marine, Theft, 36 Lashes, Lancaster, age 25

James Feagan, Marine, Insolence, 36 Lashes, Dublin, age 31

John Alson, Seaman, Neglect of Duty and Insolence, 40 Lashes, Not listed, Not listed

Richard Tobin, Seaman, Drunkenness, 36 Lashes, Cork, Ireland, age 30

Bernard Flynn, Seaman, Drunkenness, 36 Lashes, Roscommon, Ireland, age 29

George Ireland, Seaman, Drunkenness, 36 Lashes, North Shields, age 53Thursday, 26 September 1805, p. 189

John Anderson1, Seaman, Drunkenness, 36 Lashes

George Burton, Seaman, Drunkenness, 36 Lashes, London, age 19

William Beaumont, Seaman, Drunkenness, 36 Lashes, Carlisle, age 20

John Shorling, Seaman, Drunkenness, 36 Lashes

John Smith2, Seaman, Drunkenness, 36 Lashes

William Gibbons, Seaman, Drunkenness, 36 Lashes, London, age 28

James Denning, Seaman, Drunkenness, 36 Lashes

Sam Benbow, Seaman, Drunkenness, 36 Lashes, London, age 45Saturday, 5 October 1805, p. 190

John Campbell2, Cooks Mate, Drunkenness, 36 Lashes, Netherlee, age 12

David Blake, Seaman, Drunkenness, 36 Lashes, Newcastle, age 20

John Curran, Seaman, Drunkenness, 36 Lashes, County Carlow, Ireland, age 34

John Watson, Seaman, Drunkenness, 36 Lashes

John Grey, Seaman, Drunkenness, 36 Lashes, Falmouth, age 23

John Brown, Seaman, Drunkenness, 36 Lashes

John Smith3, Seaman, Drunkenness, 36 LashesTuesday, 8 October 1805, p. 190

John Mc Cormick, aka Cormick, Seaman, Drunkenness, 36 Lashes, Wexford, Ireland, age 24

George Burton, Seaman, Drunkenness, 36 Lashes, London, age 22

Benjamin Hawkins, Seaman, Drunkenness, 36 Lashes, London, age 26

James Mc Laughlin, Seaman, Drunkenness, 36 Lashes, Roscommon, Ireland, age 25

William Mitchell, Seaman, Drunkenness, 36 Lashes, Dundee, Scotland, age 56

James Smithson, Seaman, Drunkenness, 36 Lashes, London, age 25

Richard Williams, Seaman, Drunkenness, 36 Lashes, Beaumaris, Wales, age 23Saturday, 19 October 1805, p. 191 (open link to enlarge)

John Dennington, Seaman, Drunkenness, 36 Lashes

John Dunkin, Seaman, Drunkenness, 36 Lashes, County Mayo, Ireland, age 20

James Evans, Seaman, Drunkenness, 36 Lashes, Gloucester, age 29

John Hall, Seaman, Drunkenness, 36 Lashes, London, age 22

James Mansfield, Seaman, Drunkenness, 36 Lashes

John Murphy, Seaman, Drunkenness, 36 Lashes, Belfast, Ireland, age 24

William Pritchard, Seaman, Drunkenness, 36 Lashes, Anglesey, age 25

William Skinner, Seaman, Drunkenness, 36 Lashes, London, age 20, Killed in Action 21 October 1805

Henry Stiles, Seaman, Drunkenness, 36 Lashes, Thames, Oxfordshire, age 28

William Wood3, Seaman, Drunkenness, 36 Lashes, Stens, Yorkshire, age 26Tuesday, 29 October 1805, p. 195

John Matthew, Seaman, Drunkenness, 36 Lashes, New York, age 25

Richard Collins, Seaman, Drunkenness, 36 Lashes, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, age 23

Wm. Stanford, Seaman, Drunkenness, 36 Lashes, Brecknock, Scotland, age 27

John Walland, Seaman, Drunkenness, 36 Lashes, Not listed, Not listed

Charles Waters, Seaman, Drunkenness, 36 Lashes, Monmouth, England, age 27

Michael Griffith, Seaman, Drunkenness, 36 Lashes, Not listed, Not listed

James Leary, Seaman, "ships barber", Drunkenness, 48 Lashes, Wexford, Ireland, age 20

John Thomas, Seaman, Drunkenness, 48 Lashes, London, age 24

John Brown1, Seaman, Disobedience of orders, 36 Lashes, Waterford, Ireland, age 25

James Rodgers, Marine, Neglect of Duty, 24 Lashes, Kilrain, Wexford, Ireland, age 34Monday, 11 November 1805, p. 197

Moderate Breezes and Cloudy Rain at intervals, sold the effects of the deceased seaman and marines which were killed in the action of the 21st ultimaTuesday, 26 November 1805, p. 199

John Hall, Seaman, Drunkenness, 36 Lashes, London, age 22

Samuel Reece, Marine, Drunkenness, 36 Lashes, Landswell, England, age 33

John Hall, Seaman, Drunkenness, 36 Lashes, London, age 22

Robert Loughton, Marine, Drunkenness, 36 Lashes, Not listed, Not listedWednesday, 27 November 1805, p. 199

John Thomas, Seaman, Drunkenness, 48 Lashes

John Dixon, Seaman, Drunkenness, 48 Lashes, Edinburgh, Scotland, age 20

John Pain, Seaman, Drunkenness, 36 Lashes, London, age 26

Richard Powell, Seaman, Drunkenness, 36 Lashes, Cheswick, age 24

Stephen Thompson, Seaman, Drunkenness, 36 Lashes, Glasgow, Scotland, age 20

John Jackson, Seaman, Disobedience to orders, 48 Lashes, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, age 28Thursday, 28 November 1805, p. 200

William Onions, Seaman, Drunkenness and Quarrelling, 48 Lashes, London, age 20

John Samuel, Seaman, Disobedience to orders, 24 Lashes

Benjamin Wilkinson, Seaman, Disobedience to orders, 24 Lashes, London, age 20

John Morgan, Marine, Neglect of Duty, 24 Lashes, Salisbury, Wilshire, age 24

Thomas Marston, Marine, Neglect of Duty, 24 Lashes, Folshill, Warwick, age 20Tuesday, 3 December 1805, p. 200

James Dennington, Seaman, Drunkenness & Theft, 36 Lashes

William Harrison, Seaman, Drunkenness, 36 Lashes, Derby, age 28

John Stevenson, Seaman, Drunkenness, 36 Lashes, Cork, Ireland, age 32

John Howard, Seaman, Drunkenness, 24 Lashes, County Mayo, Ireland, age 23

James Archibald, Seaman, Quarrelling and Fighting, 36 Lashes, London, age 41

John Dunn, Seaman, Quarrelling and Fighting, 36 Lashes, Calder, Scotland, age 35William Robertson Recollects "a slaughtering one"51

51. Robinson, pp. 53-54.