A Documentary History of the Norfolk (Gosport) Navy Yard 1800-1861

by John G. M. Sharp

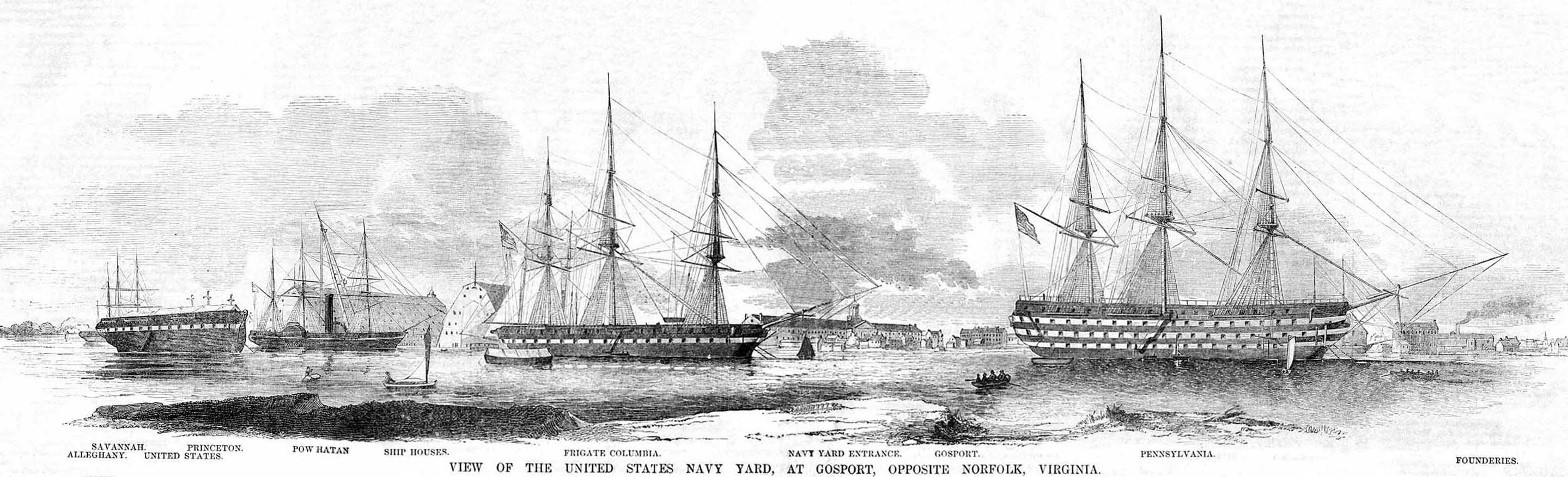

Gleason's Pictorials: Boston, July 9, 1853, Vol. V, No. 2.

PREFACE, CHAPTER DESCRIPTIONS & ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

PREFACE:

This collection of transcribed documents makes available many, for the first time, important letters and documents which cover five vital decades of the Norfolk (Gosport) Naval Shipyard. The selected documents were primarily written by or about the officers and men assigned to the shipyard and various civilian mechanics and laborers who built the vessels and armaments. This assembly includes newly found letters related to labor history, the employment of enslaved labor and the significant recruitment of black sailors prior to the Civil War. Among the new letters and documents are some regarding the employment of enslaved black women at the shipyard and naval hospital (see Chapter 13). Their subject matter included military housing, medicine, opium, pensions, desertion, robbery, murder, mental illness, the rights of naval chaplains, anxious parents, and more.

Among the letters are those from distressed parents seeking information or begging for their errant child’s discharge. Three such examples are included in the letters below. The first regards Ann Randall’s grandson Thomas Young dated 28 July 1826. Randall a free black woman claimed her grandson Thomas was illegally shipped [enlisted]. The second group of letters pertains to John Wells and Mirland Garland (see 28 September 1827) two sailmaker apprentices possibly lured by tales of adventure they heard on the Philadelphia water front. Both boys hurriedly wrote their mothers, each imploring help to secure their discharge and return to civilian life. The third (13 February 1828) relates the story of Thomas H. Steel, a forty-one year old mechanic from Alexandria, Virginia, who allegedly, “in a moment of intoxication, enlisted as an ordinary seaman.” Steel, once sober, realized what he had done and wrote desperate letters to his father requesting help to secure a discharge. While alcohol played a part in the enlistment of Thomas Steel, it figured significantly in the attempted robbery of the spirit room of the USS North Carolina, see 12 November 1827.

The chapters and documents are arranged chronologically. Each is accompanied by an introduction which discusses the background and impact of the subject on the history of the shipyard. To my knowledge many of these items have never been previously discussed or published.

Although long a fixture in the Chesapeake area for over two centuries, a comprehensive history of the Gosport Navy Yard, known today as the Norfolk Naval Shipyard, is yet to be written. Many of the existing histories are largely compendiums consisting of brief profiles of the commandants, and well known naval officers stationed at the shipyard. In these volumes civilian workers appear mainly as anonymous individuals in the photos of ship launches, indeed far more space is given to ship data and images than to the employees who actually built them.

In 1874 the shipyard’s first historian Commander Edward P. Lull, USN, wrote in his preface “how meager were the sources of trustworthy information.” As Commander Lull then observed, he was confronted with a shipyard “twice victim to fires” in which most all of the day records were destroyed.1 Many a subsequent historian has echoed Lull's lament on the lack of civilian payrolls and muster records largely destroyed in the Civil War.

1. Lull Edward P. History of the United States Navy Yard at Gosport (near Norfolk), Government Printing Office, Washington D.C., 1874, p. 2.

Today the National Archives and Records Administration, Washington D.C., has but one payroll from February 1819, a few separate sheets dated 12 May 1819 listing employee names and occupations as well as the majority of the month of July 1848 payroll.2 In preparing this volume, I made an extensive search through the correspondence files of the Secretary of the Navy in hopes of filling in some of the documentation gaps. After examining hundreds of letters, I was able to locate a substantial number of documents which provide vital information. One fortunate find was the 1846 Gosport Navy Yard Employee List. This document originally was titled “List of all Person’s Employed in the U S Navy Yard Gosport Va. with their Names, Salaries & duties” and gives a detailed look at the shipyard naval and civilian employees on the eve of the Mexican American War. The listing was originally composed on sixteen pages enumerating, 369 employees and providing their names, occupations, annual and per diem pay rates and duties assigned. The exceptional preservation and survival of this 1846 list, is a direct consequence of the document being filed with the papers of the Secretary of the Navy. The list was compiled and forwarded by the commandant of Gosport (Norfolk) Navy Yard Commodore Jesse Wilkinson at the direction of Secretary of the Navy, George Bancroft, on 2 January 1846.3

2. Sharp, John G. M., Early Gosport Documents, Gosport Navy Yard Employees, Occupation and Per Diem Pay Rates, http://www.usgwarchives.net/va/portsmouth/shipyard/sharptoc/nnysharp4.html

3. Wilkinson to Bancroft, 2 January 1846, pp 1-20, Letters Received from Captains (“Captains Letters”), 1805-1861, 1 Jan 1846 to 31 Jan 1846, volume 326, letter number 6, RG260 National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C.

Lull and his successors found what naval records that still existed were poorly indexed and widely dispersed.

Existing histories of the shipyard for the most part have little or no serious discussion of the civilian workforce. Despite its status as one of Norfolk’s historic icons, the historical literature on the shipyard itself is negligible. Notable too is the scant mention of enslaved labor during the antebellum era. Enslaved labor on United States military installations was a common sight in the first half of the nineteenth century, for agencies and departments of the federal government were deeply involved in the use of enslaved blacks. In fact, the United States military were the largest federal employers of rented or leased slaves throughout the antebellum period.4

4. Ericson, David F. Slavery in the American Republic Developing the Federal Government, 1791-1861 (University of Kansas, Lawrence Kansas, 2011), p. 135.

My purpose is not only to collect and transcribe documents relating the history of the civilian workforce but also to convey something of the workers experience. In compiling this selection I have kept editorial comment and secondary sources to the essential minimum in order to let the mechanics and laborers, to the extent possible, "speak for themselves" and to avoid what one distinguished historian has labeled the "condescension of posterity."5

5. Dibble, Ernest F. Slave Rentals to the Military: Pensacola and the Gulf Coast Civil War History Volume 23, Number 2, June 1977 pp. 101-113.

The letters of Commodore’s John Cassin, Lewis Warrington and James Barron illustrate some of the unique difficulties and circumstances which faced the shipyard. For example, on 20 June 1833 Commodore Warrington wrote to the Secretary of the Navy the following.6

6. Thompson, E. P. The Making of the English Working Class, (Vintage Books, New York, 1963), p. 12.

I am reluctantly compelled to announce that the Shipwrights of this yard struck work yesterday morning, very unsuccessfully, because they were refused higher wages then one given at the other yards – They have no doubt seized on the occasion of the Delaware admission into dock, and the known wish of the President to have her speedily equipped as a sure means of obtaining their ends, and should they succeed, there is no knowing how far they may go –

Many of the early commandant’s letters provide rich details on employment and labor issues (see Chapter 9). Despite the occasional protest, the shipyard workforce remained essentially "day laborers" who were rapidly downsized after cuts in the annual naval appropriations. Similarly during winter months when weather conditions, like strong winds and severe cold constrained workers to sustain periods of forced idleness large, numbers of employees were dismissed.

Norfolk (Gosport) Naval Shipyard nineteenth century naval payrolls and muster documents typically comprised employee name, occupation and wage rate (see Chapter 18). Placing enslaved workers on the federal payroll was often accomplished through subterfuge, though on occasion even routine deception was dropped. One glaring example occurred in 1830 when Navy Yard Commandant, Commodore James Barron, placed two enslaved women, Lucy Henley and Rachel Barron, on the shipyard payroll as "ordinary seamen" and signed for their wages.7 Some idea of the human scale can be found in this excerpt from a 12 October 1831 letter of Commodore Lewis Warrington to the Board of Navy Commissioners in response to various petitions by white workers.

7. Lewis Warrington to Secretary of the Navy, 20 June 1833, Captains Letters, Letters Received from Captains (“Captains Letters”),1805-1861, p.1, Letter no. 80, Volume 183, RG 260, National Archives and Records Administration Washington D.C.

Miscellaneous Records of the Secretary of the Navy, "Muster Rolls" 1830, p. 40, roll number 0183, RG 45, NARA Washington D.C., "Rachel Barron" enumerated as # 2, O.S. 2nd, wage $15.55 and "Lucy Henley" # 4, O.S. 2nd, wage, $15.55. Both women’s wages were signed for by Commodore James Barron.

On 6 December 1845 Commodore Jesse Wilkinson confirmed to the Secretary of the Navy, the long standing practice of placing enslaved laborers on the rolls of the shipyard. In his letter he stated, “that a majority of them [blacks] are negro slaves, and that a large portion of those employed in the Ordinary for many years, have been of that description, but by what authority I am unable to say as nothing can be found in the records of my office on the subject – These men have been examined by the Surgeon of the Yard and regularly Shipped [enlisted] for twelve months."8

8. Wilkinson to Bancroft, 6 December 1845, Letters Received from Captains (“Captains Letters”), 1805 -1885, 1 Nov 1845 to 31 Dec 1845, Volume 325, Letter number 84, pp. 1-2, RG 260, National Archives and Records Administration Washington D.C.

George Teamoh, a former enslaved laborer, ship caulker and carpenter who toiled at the Norfolk Navy Yard Ordinary in the 1840s, spoke for many when he pointed to the unpleasant but undeniable truth, "The government has patronized and given encouragement to Slavery to a greater extent than the great majority of the country has been aware. It had in its service hundreds if not thousands of slaves employed on government work”. He recalled, "Slavery was so interwoven at that time in the very ligaments of that to assail it from any quarter was not only a herculean task, but on requiring great consideration caution and comprehensiveness."9

9. Teamoth, George, God Made Man Man Made the Slave The Autobiography of George Teamoth editors F. N. Boney, Richard L. Hume and Rafia Zafar (Mercer University Press: Macon 1990), p. 83.

CHAPTER DESCRIPTIONS

Chapter 1, Andrew Sprowle, 1710 -1776: “Lord of Gosport” http://www.usgwarchives.net/va/portsmouth/shipyard/sharptoc/asprowle.html

This first chapter takes a close look at the founder of the Gosport shipyard Andrew Sprowle. Examination of his 1776 will and his wife Katherine Hunter Sprowle’s claim against the British crown for confiscated or destroyed property confirmed, Sprowle was one of the largest slaveholders in the region. These documents reveal his highly trained enslaved workforce was integral to both his shipyard and other businesses.1, 2 In addition, the documentary record, clearly confirms Sprowle was a slave trader. In the 1740s and 1750 he owned three merchant vessels the St. Andrew, Providence and the Glasgow, which made transatlantic voyages; and carried several hundred enslaved Africans to the Caribbean and the Chesapeake.3

1. UK American Loyalist Claims, 1776-1835, AO 12-13, Katherine Sproule, aka Katherine Sprowle.

2. Sprowle, Andrew, “formerly of Milton but late of Gosport", will filed, 22/1/1779, Edinburgh Commissary Court, CC8/8/124.

3. Donnon, Elizabeth, Documents Illustrative of the Slave Trade to America, Volume IV, (Carnegie Institute, Washington D.C., 1935), pp. 162m, 218, 219, 221, 732, citing Sprowl aka Sprowle Andrew https://archive.org/details/documentsillustr00donn_2/page/218/mode/2up?q=sprowl accessed 5 August 2021.

Chapter 2, Early Loyalty and Citizenship Requirements for Federal Employees at Gosport and other Naval Shipyards http://www.usgwarchives.net/va/portsmouth/shipyard/sharptoc/nnysharp.html#loyalty

This chapter explores early loyalty oaths and citizenship requirements as the Department of the Navy reacted to rising nationalism and questions of employee allegiance.

Chapter 3, Rules and Regulations at Gosport Navy Yard 1800 http://www.usgwarchives.net/va/portsmouth/shipyard/sharptoc/gosportrules.html

This chapter contains the first rules of the Gosport Navy Yard, written in 1800, by Josiah Fox, Naval Constructor

Chapter 4, Early Apprentices at Gosport Navy Yard

http://www.usgwarchives.net/va/portsmouth/shipyard/sharptoc/nnysharp.html#apprenticesToday Norfolk Navy Yard apprentices are hired through a very centralized merit system which is highly regulated, the actual hiring process usually involves the HRO, the shipyard departments, etc., but in the early nineteenth century all shipyard apprentices were hired directly by master mechanics not the yard.

Chapter 5, The Early Organization of the Navy Yard

http://www.usgwarchives.net/va/portsmouth/shipyard/sharptoc/orgshipyard.html

From its founding as a federal naval shipyard, Gosport Navy Yard was a highly structured organization. This chapter provides a glimpse of the trade hierarchy with a list of the master mechanic who headed the various shops and departments in 1819.Chapter 6, Regulations re Musters of Civilian Employees Naval Shipyard Gosport 1821

http://www.usgwarchives.net/va/portsmouth/shipyard/sharptoc/nnysharp.html#regulations

Naval regulations required a daily muster of all Gosport Navy Yard employees. At musters, employees were required to state their names as present for work to the Clerk of the Check who was required to record each name present and absent on the daily muster rolls for pay purposes. Shipyard musters were usually conducted in the early morning and afternoon. For shipyard employees a failure to attend a muster was serious offense which could result in loss of pay or discharge. All employees were per diem workers with no entitlement to sick or annual leave.Chapter 7, The Disastrous Voyage: Yellow Fever aboard the USS Macedonian and USS Peacock, 1822 http://www.usgwarchives.net/va/portsmouth/shipyard/sharptoc/yf1822.html

In the early annals of the U.S. Navy no more lethal service is recorded than that of naval vessels in the West Indies from 1822 to 1825. During these years the navy lost more officers and men, in proportion than any other service in which they were ever engaged. Their most deadly culprit was not a foreign fleet or piracy but virulent yellow fever. In the ensuing decades as American naval and merchant vessels sailing in the Caribbean unknowingly became vectors for a variety of dangerous viral diseases such as yellow fever and which repeatedly visited the Chesapeake.

Chapter 8, Dr. Isaac Hulse, Surgeon USN

http://www.usgwarchives.net/va/portsmouth/shipyard/sharptoc/nnysharp11.html

In 1821 Dr. Isaac Hulse was assigned to the Naval Hospital at Norfolk, Virginia, where he remained for four years. On 14 June 1825 the Gosport Case files reflect “Dr. Hulse, Surgeon’s Mate, of this establishment has been promoted to Surgeon in the Navy on the 5th of the present month.” Hulse spent much of his career treating yellow fever; he himself probably came down with malaria and yellow fever during his time at Gosport Naval Hospital. The remainder of his naval career was spent as chief physician at Naval Hospital Pensacola or on ships operating in the Caribbean.Chapter 9, Letters from and to the Gosport Navy Yard 1826-1828 http://www.usgwarchives.net/va/portsmouth/shipyard/sharptoc/nnysharp14.html

Letters and documents are the keys to unlocking the past; they are history in the raw. The following selected and transcribed letters were written 1826-1828 to Commodore James Barron and the Secretary of the Navy Samuel L. Southard. The authors of these letters were a variety of officers, seaman and civilians who made up the Gosport (Norfolk) Navy Yard community. These documents bring to life the teeming, noisy, contradictory and sometimes violent world of Gosport. The letters describe military housing, medicine, opium, pensions, desertion, robbery, murder, a free black woman, mental illness, the rights of naval chaplains, anxious parents, and more. Today these fascinating manuscripts remain a mirror that allows us to peer into the past and view the hopes, concerns and dreams of this now vanished generation.

Chapter 10, Smallpox

http://www.usgwarchives.net/va/portsmouth/shipyard/sharptoc/judson.htmlSmallpox a now eradicated viral disease, single–handedly distorted the history of health and mortality in the eighteenth and early nineteenth century.4 This disease repeatedly struck the United States causing death and disfiguring scars (see Chapter 1). Military vaccination programs began during the American Revolution. During the administration of President James Monroe, vaccination programs for seamen were begun. Dr. Elnathan Judson’s 1823 report to the Secretary of the Navy on the successful vaccination of 161 naval seamen in the Boston area for small pox contained important demographic and ethnic data. In his report Dr. Judson breaks down the number of men vaccinated during the three month period and, remarkable for the era, his report contained the seamen’s demographic and ethnic data with self-reported ages and country of birth.1 Noteworthy too; Dr. Judson enumerated the names, ages and country of origin for all the seamen vaccinated. For black seamen he distinguished between those born in the United States and those born in England.

4. Harper, Kyle Plagues Upon the Earth Disease and the Course of Human History (Princeton University Press, Princeton, 2021), p. 363.

Chapter 11, The Recruitment of African Americans in the U.S. Navy, 1825-1839

http://www.usgwarchives.net/va/portsmouth/shipyard/sharptoc/nnysharp8.htmlIn 1839 African Americans made up 12% of the United States Navy. That year, of the 180 men, the recruiting station at Norfolk, Virginia, took in, 8.89% were black. This chapter contains a transcription and analysis of a long overlooked memorandum from Commodore Lewis Warrington to the Secretary of the Navy concerning the number of enlisted men entered into the U.S. Navy during the period subsequent to 1 September 1838. The memorandum itself was compiled and dated September 17, 1839, probably by the officers of the receiving ship Java, then stationed at Norfolk, Virginia. The document breaks out the number of men entered from five naval recruitment stations at Boston, New York, Philadelphia, Baltimore and Norfolk. Remarkably for this time period, and of great importance to scholars, the actual number of black men who were entered into the navy is given both as a total and is specified for each naval station.

Chapter 12, Dr. Thomas Williamson and Mental Illness at Gosport (Norfolk) Naval Hospital 1827-1844

http://www.usgwarchives.net/va/portsmouth/shipyard/sharptoc/drwilliamson.htmlIn early nineteenth century America mental illness was poorly understood. The records of two transcribed cases below illustrate how early naval medicine and the staff of Gosport (Norfolk) Naval Hospital attempted to treat mental illness. For those afflicted, it was not uncommon that they would be considerably neglected, often left alone in deplorable conditions or in shackles. Dorothea Dix's (1802-1887) incipient efforts to reform and improve mental health facilities and care for the mentally ill were still in infancy. Dix would later advocate for the building of state hospitals to house the indigent insane. Surgeon Dr. Thomas Williamson USN and the staff of the Gosport Naval Hospital, (despite pleas for better facilities) never had adequate resources to care for those with long term mental problems.

Chapter 13, Norfolk (Gosport) Naval Hospital Female Employees 1810 to 1842

http://www.usgwarchives.net/va/portsmouth/shipyard/sharptoc/gnhaafworkers.htmlThis chapter examines the largely forgotten but crucial part African American labor played at the Gosport (Norfolk) Naval Hospital, especially the role of black women which became paramount in the provision of patient care and sustenance. These enslaved women both lived and worked at the hospital as care providers. There they served during the War of 1812, the awful yellow fever epidemics of 1821 and 1855 and the great cholera epidemic of 1832. At great risk to themselves, they helped nurse and feed the sick and dying. While many historians have written about medical care, the participation and contributions of black women as nurses and hospital workers at Gosport in the antebellum era have often been overlooked.

Chapter 14, Commodore Lewis Warrington writes to the Board of Navy Commissioners on the employment of enslaved workers in the construction of Stone Dock, 12 October 1831

http://www.usgwarchives.net/va/portsmouth/shipyard/sharptoc/nnysharp.html#enslavedFor the dry dock workers and other whites, fear of enslaved labor was intensified by the failed slave rebellion led by Nat Turner. Turner's revolt began on 22 August 1831 with the killing of 55 whites, quickly followed by widespread destruction and chaos as numerous militias organized in retaliation against the slaves. The State of Virginia hurriedly executed 56 slaves accused of being part of the rebellion. In this frenzied aftermath, many innocent enslaved people were punished. Scholars content at least 100 blacks, and possibly up to 200, were killed by militias and mobs. Commodore Warrington's response reviewed and endorsed the information provided by Chief Engineer Baldwin which stressed the perceived economic benefits to the government as well as the overall efficiency to the project as justification for continuation of enslaved labor in the building of the Dry Dock. The BNC supported Commodore Warrington's decision and denied the stone cutters petition. Fear of a large scale servile rebellion ultimately subsided, but chattel labor continued at Gosport and other naval ship yards until the coming of the Civil War.

Chapter 15, Cholera at Gosport Navy Yard 1832

http://www.usgwarchives.net/va/portsmouth/shipyard/sharptoc/nnysharp5.html

Cholera was one of the greatest killers of the nineteenth century. In 1832 the disease was unfamiliar with no cure and consequently terrifying. This chapter contains important but little known letters of Commodore Lewis Warrington to the Secretary of the Navy, Levi Woodbury, during the awful summer of 1832. The letter chronicles how cholera roared through the navy yard and the Gosport community.

Chapter 16, Dry Dock No 1, a Work Stoppage & the USS Delaware in Letters & Documents including Quarterly Report of Persons Confined & Punished aboard the U.S. Ship Delaware

http://www.usgwarchives.net/va/portsmouth/shipyard/sharptoc/dd1-delaware.htmlOn 20 June 1833 Commodore Lewis Warrington acknowledged his workforce was unhappy, they were on strike. “I am reluctantly compelled to announce that the Shipwrights of this yard struck work yesterday morning, very unsuccessfully, because they were refused higher wages then one given at the other yards…” The Commodore saw no need to negotiate. The workers were never united, and through a combination of both intimidation and division all the men quickly resumed work. In this early confrontation management held the trump card. Even the most disgruntled white workers were keenly aware, that as free labor they were in a precarious situation. Enslaved labor made up at least one third of the shipyard workforce and many of the slaveholders themselves were naval officers and master mechanics.

Chapter 17, Norfolk Navy Yard Slaveholders Petition to the Secretary of the Navy, June 21, 1839

http://www.usgwarchives.net/va/portsmouth/shipyard/sharptoc/nnysharp6.htmlJust how fundamental enslaved labor was at Gosport Navy Yard is readily apparent in this extraordinary letter of 21 June 1839. In the letter Commodore Lewis Warrington writes to Secretary of the Navy, James K. Pauldin, and enclosed a memorial (petition) from the shipyard’s thirty-seven disgruntled master mechanics and workmen appealing a Navy decision to curtail enslaved labor. This little known letter and petition provide a unique glimpse into the world of slaveholders and the work practices of the Department of the Navy and the Norfolk Navy Yard.

Chapter 18, The Gosport Navy Yard Apprentice Boys School and the question of foreign birth, June 7, 1839

http://www.usgwarchives.net/va/portsmouth/shipyard/sharptoc/nnysharp7.htmlFear of immigrants is nothing new. In the 1830’s the Norfolk Apprentice Boys School became a subject of contention as nativism; that is fear and hatred of aliens, particularly religious or ethnic minorities such as Irish and German Catholics began to surface in American, politics. Commodore Warrington and Captain Charles Whlennes, apparent unease with “foreign” born sailors reflects increasing anxiety of the era

Chapter 19, List of Gosport Navy Yard Employees Military and Civilian, 1846

http://www.usgwarchives.net/va/portsmouth/shipyard/sharptoc/nnysharp13.htmlFew complete Gosport Navy Yard muster or payrolls survived the devastating fires of the Civil War. Fortunately, in 1845 the Secretary of the Navy, George Bancroft, required all naval shipyards to forward an up-to-date list to Washington D.C. This chapter contains a fully transcribed List of all Person’s Employed in the U S Navy Yard Gosport Va. with their Names, Salaries & duties, and was originally composed of sixteen pages of 369 of employee's names, occupations, annual and per diem pay rates and duties assigned.

Of equal importance, in a separate note Commodore Jesse Wilkinson confirmed a long standing Gosport subterfuge to the Secretary of the Navy of employing enslaved labor on the naval payroll as seamen. He wrote, “that a majority of them [blacks] are negro slaves, and that a large portion of those employed in the Ordinary for many years have been of that description, but by what authority I am unable to say as nothing can be found in the records of my office on the subject.” Today this surviving 1846 employee list allows scholars to closely study the impact of enslaved labor.

Chapter 20, Flogging at Sea, Discipline and Punishment in the Old Navy 1846-1847

http://www.usgwarchives.net/va/portsmouth/shipyard/sharptoc/oldnavydiscipline.htmlIn the early United States Navy flogging was the most common means of enforcing discipline. Its defenders considered flogging swift and effective; in contrast to confinement, it quickly returned a sailor to duty. The majority of naval officers, and probably some enlisted as well, believed that flogging was the only practical means of enforcing discipline on board ship. Nonetheless as critics of the practice grew more vocal, the U.S. Congress demanded the Department of the Navy compile statistics for flogging on each ship to track how pervasive and to what extent flogging was utilized. These reports began in the years 1846-1847. Also in 1846 in response to increased public and congressional complaints, the Secretary of the Navy set the legal limit for flogging at twelve lashes.

Chapter 21, Station Log Entries for the U.S. Navy Gosport

http://www.usgwarchives.net/va/portsmouth/shipyard/sharptoc/gosportlog.htmlWe have the only surviving log or journal for Gosport Navy Yard prior to the Civil War. This chapter contains a transcribed selection of the day to day of activities in 1850 of the shipyard workforce.

Chapter 22, Resignations and Dismissals at Norfolk Navy Yard from the U.S. Navy April 1861

http://www.usgwarchives.net/va/portsmouth/shipyard/sharptoc/dismissals1861.htmlIn 1861, 373 naval officers resigned their commissions and of these approximately 311 became commissioned or warrant officers of the Confederate States Navy The transcribed letters below represent some of these resignations received by the Secretary of the Navy from the officer’s stationed at Norfolk in 1861 or on naval vessels home ported there.

Transcription: This work required extensive transcriptions of microfilm and photographic images of muster and employee lists from the collections of National Archives and Records Administration and the District of Columbia Archives. I have striven to adhere as close as possible to the original in spelling, capitalization, punctuation and abbreviation (e.g. "Do" or "do" for ditto or same as above) including the retention of dashes, ampersands and overstrikes. Where I was unable to print a clear image or where it was not possible to determine what was written, I have so noted in brackets. Where possible, I have attempted to arrange the transcribed material in a similar manner to that found in the letters and enclosures. All transcriptions of documents quoted are mine.

Language: These documents are transcriptions of original eighteenth and nineteenth century documents and letters. The racial designations therein are those used in the original while still others may reflect racist and xenophobic opinions and attitudes. Most of these historical documents and excerpts cited below were created during the nineteenth century and reflect the predominant attitudes and language of that era

This history would not be possible without two scholars who began to reexamine the early history of the Norfolk (Gosport) Navy Yard and its reliance on enslaved labor. The late Robert S. Starobin, whose classic 1970 Industrial Slavery in the Old South, in his review of the labor rolls of Gosport Naval Shipyard, first impressed on me that enslaved labor provided a viable, profitable and above all flexible workforce at the shipyard during the 1830’s,1, 2 and to Christopher Tomlins, author of “In Nat Turners Shadow, Reflections on the Dry Dock Affair of 1830-1831” and ''In the Matter of Nat Turner: A Speculative History'' for his thoughtful and insightful analysis of the dry dock dispute 1829-1832 and the Nat Turner Rebellion.3, 4

1. Starobin, Robert S. Industrial Slavery in the Old South, Oxford University Press, New York, 1971), p. 159.

2. Lichtenstein, Alex, “Industrial Slavery and the Tragedy of Robert Starobin,” Reviews in American History, vol. 19, no. 4, (Johns Hopkins University Press, 1991), pp. 604-17.

3. Tomlins, Christopher L. (1992) In Nat Turner's Shadow: Reflections on the Norfolk Dry Dock Affair of 1830-1831, Labor History, 33:4, 494-518, DOI: 10.1080/00236569200890261

4. Tomlins, Christopher, In the Matter of Nat Turner: A Speculative History, (Princeton University Press, Princeton, 2020) pp. 152-163

Thomas Hulse's work on military slave leasing greatly influenced my thoughts on how the leasing of enslaved labor by the military contribute to its large scale expansion. While focused on Florida, his seminal 2010 study “Military Slave Rentals, the Construction of Army Fortifications and the Navy Yard in Pensacola, Florida, 1824-1863, has far larger implications.5

5. Hulse, Thomas, “Military Slave Rentals, the Construction of Army Fortifications and the Navy Yard in Pensacola, Florida, 1824-1863,” The Florida Historical Quarterly 88, no. 4 (Spring 2010), 504.

I owe a special debt to Chris Killillay, Archives Specialist, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C., who has graciously shared his expertise and patiently answered my many questions, and helped me locate those rare but significant mentions of enslaved individuals contained in the letters, documents and station logs.

My friend the late Glenn E. Helm, Director of the Navy Library, Washington DC, was ever helpful with advice and encouragement for this project. Glenn cordially gave me his valuable time and unrivaled knowledge of this wonderful institution’s incredible resources. Glenn will be missed.

Robert B. Hitchings carefully looked over these articles and made valuable suggestions throughout.

My thanks to Donna Bluemink, my editor, for her extraordinary research and unique knowledge of history of Norfolk and Portsmouth, Virginia, during 1855 yellow fever epidemic. Her many valuable suggestions have improved this manuscript.

Finally my thanks, gratitude and love to my wife Gene who has lived with this book, provided valuable suggestions and always gave me her unswerving encouragement and support.John G. M. Sharp

25 October 2021