FROM PENSACOLA NAVY YARD TO BALTIMORE:

A MURDER IN BALTIMORE AND A SAILOR ON THE RUN

By John G. M. Sharp

At

USGenWeb Archives

View of the Baltimore Harbor

"This is an ordinary, although an atrocious instance of crime."

Edgar Allen Poe, the Mystery of Marie Roget, 1842

Introduction: This essay traces the story of an 1846 murder that took the life of a young man on the streets of Baltimore. Baltimore in the 1840’s was a city of promise and peril. As the nation celebrated July 4th, a brutal killing took place on Clay and Park Streets. This homicide was one of many that year, but the crime quickly drew national attention and a nationwide manhunt. The popular newspapers and penny press of the day closely followed and dramatically related the story of the chief suspect, Lewis Cummings, his hasty flight, enlistment in the U.S. Navy, his long period of evasion and eventual apprehension at the hands of two determined private detectives. Cummings' subsequent murder trial in 1848 for the death of Leplat Carter packed a hushed Baltimore court room. Before the jury, the prosecutor gave graphic testimony, presented numerous eye witnesses and made headline news. This Baltimore murder reflects the travails and lapses of the nineteenth century criminal justice system. This essay highlights the problems, continuities and transformation of state and federal law enforcement in pursuit of serious felons. The documents, letters and contemporary newspaper accounts upon which this narrative is based are all transcribed below.

Dedication: for Robert Martin, Police Captain, retired, Jersey City, New Jersey, optimis viris

John G. M. Sharp 4 November 2020

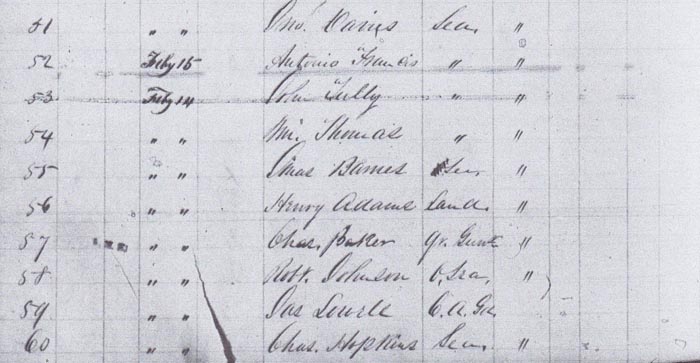

Prologue: On 1 October 1847 Captain W.K. Latimer, Commandant Pensacola Navy Yard, received a letter from Secretary of the Navy, John Y. Mason, concerning the murder of Leplat Jerome Carter which took place in Baltimore on 4 July 1846. Among the enclosures was a letter from two Baltimore "police officers" John Zell and Archiband G. Ridgely with details of the crime and requested assistance in apprehending a suspect. The two men wrote the name of the alleged culprit as Lewis Cummings, aka "Henry Adams" Landsman, USN. Latimer confirmed that a Henry Adams was indeed part of the crew of the sloop-of-war, USS Decatur.1 Zell and Ridgley though were not "police officers" but in fact private detectives famous and infamous for apprehending suspects charged with murder, robbery and "slave stealing", otherwise known as capturing fugitive slaves and those who assisted them.2 In one notorious incident at Columbia, Pennsylvania, Ridgely while pursuing two fleeing slaves, shot and killed William Smith, one of the hunted men.3, 4 Ridgely later fled to Baltimore and was able to plead the shooting was justified.5

1 Muster Roll 1847, USS Decatur, Miscellaneous Records of the Navy Department, RG 45, "Henry Adams", Landsman, muster number, 56.

2 The Lancaster Examiner (Lancaster, Penn),10 September 1902, p. 1.

3 Monongahela Valley Republican (Monongahela, Penn) 7 May 1852, p.2.

4 The Liberator, (Boston, Mass), 28, May 1852, p.2, "the Killing of a Fugitive Slave at Columbia." At Columbia Snyder and Ridgely in pursuit of a fugitive slave named William Smith. Officer Ridgely shot and killed Smith who was struggling to get away.

5 Lancaster Intelligencer (Lancaster, Penn), 16 May 1852, p.2 Ridgely returned to Baltimore and pleaded the shooting was justified, case was later dropped.

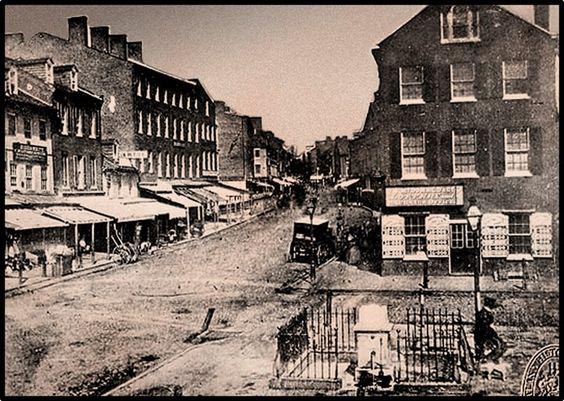

Baltimore Street, Baltimore 1849, in the earliest photo of the city.The Murder: The murder of Leplat Carter took place in Baltimore on a rainy and warm 4th of July afternoon. That morning began with the traditional firing of cannons, church bells rung, the Declaration of Independence scheduled to be read aloud with appropriate ceremony and fireworks later for the night sky. A surprise rain and a hard north eastern wind blowing abruptly postponed most festivities and parade plans. The civic organizations which were scheduled to march hastily adjourned to local taverns. 6, 7

6 The Baltimore Sun, (Baltimore, Maryland), 4 July 1846, pp. 1-2.

7 Melton, Tracy Matthew Hanging Henry Gambrill: The Violent Career of Baltimore's Plug Uglies, 1854-1860, (Maryland Historical Society, Baltimore, 2005), p. 169.

Regardless of weather, Baltimoreans like to revel and celebrate loudly. As usual on the 4th of July, the local clubs and gangs celebrated the nation’s independence by drinking, carousing, and fighting at popular recreational spots. One such place in the Western District was located at Park and Clay Street near Lexington Market. That evening The Baltimore Sun reported a vicious killing that took place on that corner, "Our city on Saturday afternoon was the scene of a disgraceful affray, which resulted in the death of a young man, about 19 years of age named Leplat Carter."8 The reporter then related a tragic tale of how a group of young men and women had spent the afternoon of the holiday, "drinking and carousing." Sometime between 3 and 4 o’clock an argument began which resulted in Louis Cummings being charged with stabbing Leplat, alias, "Life" Carter to death with a large Bowie knife. Other witnesses claimed the deadly weapon was dirk or stiletto.9 Baltimore Mayor Jacob G. Davies was near the location of the murder and did his best, he later claimed"… to quiet the disturbance and was there at the time of the murder, but his presence failed to arrest the design of the murderer".10 Mayor Davies saw Cummings with the raised knife. Cummings quickly fled the scene with help from others. Davies quickly posted a $ 300 reward for his capture. 11, 12

8 The Baltimore Sun, (Baltimore, Maryland), 4 July 1846, p. 4.

9 The Baltimore Sun, (Baltimore, Maryland), 6 July 1846, p. 2.

10 The Baltimore Sun, (Baltimore, Maryland), 6 July 1846, p. 2.11 Baltimore Daily Commercial (Baltimore, Maryland), 7 July, 1846, p. 2.

12 Jacob G. Davies Mayor of Baltimore 1844-1848.

Despite this substantial reward, the Baltimore Daily Commercial on 5 December 1846 reminded the police and the public, "Still among the Missing. It is somewhat irregular that Lewis Cummings, the murderer of Leplat Carter, has not up to this time been heard of. Does no person know of his hiding place? Would not a large reward force him out?13

13 Baltimore Daily Commercial (Baltimore, Maryland) 5 December 1846, "Still among the Missing It is somewhat irregular that Lewis Cummings, the murderer of Leplat Carter, has not up to this time been heard of. Does no person know of his hiding place? Would not a large reward find him out?"

Mob City

Baltimore during the nineteenth century was one of the most violent municipalities in America.b14 Baltimore’s rapid growth, influx of newcomers, exaggerated group loyalties had repeatedly triggered racial, ethnic, religious and political tensions which erupted into at least a dozen riots and hundreds of small gang wars between 1820 and 1865.15 According to social scientist Robert J. Brugger, "violence in Baltimore, was fairly rampant in the 1840’s and 1850’s."16 Two of the worst examples are the 1856 "Know-Nothing Riot" and 1861 "Pratt Street Riot". Election mayhem plagued nineteenth century Baltimore, as polling places were located in predominantly native-born districts where immigrants travelling to these voting places were often targeted by nativist rivals.17 Violence repeatedly broke out in Baltimore on days when men such as Cummings and Lepalt were not at work, and was very likely to erupt during weekend activities such holidays, sporting events and festivals.18 For many, knives were the weapon of choice. Cummings was not unusual, many young men carried Bowie knifes, stilettos dirks and other edged weapons and some like Cummings used them to settle trivial disputes. For others knifes were tools of their trade such as carpenters, butchers and sailors, being kept concealed for protection. Baltimore newspapers variously reported that Cummings' knife was a Bowie knife, Spanish knife and a dirk. A dirk is a long thrusting knife without a handguard, but what all these weapons had in common was they were easy to conceal, intimidating and a thrust or stab wound often brought blood poisoning and frequently proved fatal.19

15 The Oxford Companion to United States ,History editor Paul S.Boyer (Oxford University Press, New York,2001),p.166 New York City and Philadelphia experienced similar riots.

16 The Baltimore Sun, 1 November 1992, Shane Scott, "Violence is an old story in Mob Town".17 Baker, Jean H., Ambivalent Americans: The Know-Nothing Party in Maryland Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore,1977), p. 132.

18 Ibid, p.131.19 Chisholm, Hugh (ed.), Dagger, The Encyclopedia Britannica, 11th ed., Vol. VII, New York, NY: Cambridge University Press (1910), p. 729.

Lewis Cummings

Lewis Cummings had a history of violence. Born in Maryland about 1819 both Cummings parents had emigrated from Canada. His two younger sisters, Mary and Sophia, both later worked as seamstresses. Lewis had some early schooling and could both read and write. Later he apprenticed as a "tinner" or tinsmith. Tinners were those who made and repaired things made of tin or other light metals.20 At the shipyards of Baltimore, tinsmiths worked on ship stoves and related piping. Like many young men, however, Lewis chose to spend his time in the waterfront bars and bordellos where a young unattached man could affirm through demonstrations of toughness with a reputation as someone to fear. His penchant for this new way of life led to Park and Clay Street where he made a living as a thief, hired thug and pimp. His first serious run in with the law though was his arrest and conviction in March 1839 for "murderous assault with an iron tree swing upon two other men with the intent to kill." In May 1839 he was sentenced to three years in jail.21 His sentence though was quickly commuted to time served and a $ 500 fine. On 7 May1840 Cummings was again committed to jail for assault and battery of Henry Lyman."22

20 1860 and 1880 United States Federal Census, Baltimore, Maryland.

21 The National Gazette (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania), 19 March 1839, p. 2.

22 The Baltimore Sun (Baltimore, Maryland), 7 May1840, p .2, "Lewis Cummings, for and assault and battery on Henry Lyman, committed to the jail."

Despite rising murder and manslaughter rates in the 1840’s, Baltimore juries rarely delivered a guilty verdict, in fact they found just six men guilty of murder in the first degree. Baltimore jurors were reluctant to impose the death penalty, with only one convicted in 1840’s to hang.23 Why such hesitancy? Baltimoreans were more pugnacious than their neighbors and fights and violent conflicts were commonplace.24 Most citizens lived close together; consequently jurors often came from the same neighborhood as the accused. The names of the 12 jurors were printed in the Baltimore Sun often the day of the trial, thus the possibility of social pressure, intimidation and threats to jurors, their families and livelihoods increased.25 Jurors were not drawn by lottery but selected by the Sheriff, a political post thus making jury packing a constant threat.26 Threats to witnesses were reportedly commonplace, gang toughs would often hang around the court house itself. All this was compounded with the possibility of a Maryland Governor granting a pardon to allies and friends; witnesses and jurors rightly feared retaliation and thus further inhibiting prosecutions.

23 Melton, Ibid., p.266

24 Pinker, Steven, The Better Angels of our Nature Why Violence Has Declined (Viking Press, New York, Viking Press, 2011), pp. 96-97.25 The Baltimore Sun (Baltimore Maryland) 9 February 1848, p.1, twelve jurors are listed with one alternate.

26 Melton, Ibid p.368 The regulations governing juror selection were finally changed in the late 1850’s. These changes removed the authority from the sheriff and established a lottery system.

The Baltimore Sun wrote Cummings was,, "about 28 years of age, five feet eight or nine inches in height, and stout, nose slightly turned up – face rather round, and fully freckled and in conversation has a loud strong voice and speaks positively. There are believed marks of Indian ink on one of his arms.28 Except for sailors, tattoos were rare on the nineteenth century America males. Cummings though would have been familiar with tattooed sailors on the Baltimore waterfront and in the bars and bawdy houses. Cummings had neither prior service in the United States Navy nor any known maritime experience before 1846. Most likely he acquired his ink while in prison from 1839 to 1840 to enhance his appearance with a rough image.29

28 The Baltimore Sun (Baltimore, Maryland), 8 July 1846, p. 2.

29 Sharp, John G.M., American Seamen’s Protection Certificates & Impressment 1796-1822 http://www.usgwarchives.net/va/portsmouth/shipyard/aspc&i.htmlIn overall guise the Baltimore Sun claimed Cummings "was said to have worn a tweed frock coat and white hat with crape around it on the day of the murder. He also wore his neck handkerchief very low exposing his neck. He has at all times a sullen look and in costume as well as general appearance represents pretty accurately what is termed "rowdy."30 Such garb was a staple of working class life. Some like Cummings were members of violent gangs, pimps and loafers, later notorious for instigating Baltimore political riots. Others were artists and writers such as the poet Walt Whitman who simply adopted the rough persona. In his photo for his first book of poems Whitman confronts the reader with a … "bearded face and a muscular physique, casual workman's trousers, open collar, cocked hat, and arm akimbo in a strikingly …which deliberately mirrors the coarse appearance of the working class rough…"31

30 The Baltimore Sun (Baltimore, Maryland), 8 July 1846, p. 2.

31 The Walt Whitman Archive "Roughs" Baker, Danielle L. and Donald C. Irving, https://whitmanarchive.org/criticism/current/encyclopedia/entry_637.html accessed 27 October 2020.

Leplat Jerome Carter

Sadly there is no substantive information about Leplat Jerome Carter, aka Life Carter, the victim. From the sparse data provided in the Baltimore press, Carter was about 19 or 20 years of age. No other personal details appeared in the various accounts of his murder or any mention of his appearance, occupation or family. A review of the Baltimore Sun and Baltimore Daily Commercial from 1835 to 1848 reflected that Carter sole run-in with the law was his arrest for "Throwing stones at the encampment of Volunteers on Sunday afternoon by the police and that he was fined $1.00 and costs."32

32 Baltimore Daily Commercial (Baltimore, Maryland), 19 May 1846, p. 2.

Cummings' Associates

Cummings' associates were Mary Bushrod, Matilda Oliver, William Thompson and Frederick Konig. Each had numerous prior encounters with the law and all were charged as accessories to murder.

Foremost was Fredrick Konig AKA “the Boss” Konig”, born about 1822, who had a long criminal record which included; assault, disorderly conduct, riot and in 1841 murder.33 On 6 November 1841 Frederick Konig was sentenced to seventeen years and ten months for the murder of John Bigham. Konig and four accomplices were said to be members of “Swingtree Club ", who “armed with a swingtree took ferocious pleasure to attack some unfortunate individual.” On 9 May 1844 Konig and his accomplice all received a pardon from Francis Thomas, the Governor Maryland. Like Cummings Konig had a history of violence. In 1847 Konig was indicted for smashing up a house of prostitution, and attacking police officers with other members of “the Blood Tubs.”34

William H. “Country” Thompson had a long record of infamy, violence, and assault with intent to kill. Born about 1828, his nickname came from his years spent in the countryside outside of the city. In the early 1840’s he returned to Baltimore where he worked as apprentice bricklayer, and became associated with the New Market Fire Company. Here he quickly became known for his prodigious strength, fearlessness, and ability as bareknuckle and knife fighter. On 8 January 1857 his luck ran out, during a ball at the Maryland Institute, a fight broke out. In the ensuing brawl Thompson was smashed on the head and knifed in neck with a “good sized pen knife that penetrated the brain”, he died two days later of his wounds. Despite the fact that many individuals at the ball saw the fight, no witnesses came forward. His 14 January funeral was a large affair attended both “by relatives and personal friends, who occupied a train of carriages, whilst the members of the New Market Engine and United States Hose companies followed on foot, the former company displaying a handsome silk flag. The cortege proceeded to the Baltimore Cemetery, where the interment took place.”

Mary Bushrod sometimes known as “Polly Bushrod” and Matilda Oliver, were well known to police. Both women had extensive criminal records for prostitution, assault and theft. Matilda Oliver was a free black, both women were labeled in the local press with the Victorian euphemism for sex workers as “nymphs of the pave." The Baltimore Sun, 25 August 1841, Watch Returns noted Mary Bushrod was brought in for rioting and attempting to rescue another prisoner from the hands of an officer and committed to jail by Justice King.

In 1845 the two women were reported as operating out of a bawdy house on Park Street. Park Street in the 1830’s and 1840’s was notorious for its brothels. In the early 1840’s Park Street was a brothel district. On 29 January 1845, Polly Bushrod was indicted for “Highway Robbery” along with her accomplice Francis Turner, alias Elizabeth Francis Boyd. The two were arrest by officers “Hays, Zell & Co on suspicion of having robbed Mr. Christian G Peters of a silver watch on Park Street.” The Sun reported Polly used the alias Cummings. It is possible Polly may have been Cummings common-law wife. The Baltimore Sun reported that on 11 March 1846, “Matilda Oliver, Sarah Hughes and Mary Bushrod were charged with assaulting and beating Elizabeth Smith in a house on Park Street, they were all held till they posted bail.” In yet another separate incident in May 1846, Mary Bushrod and Matilda Oliver were “charged with an assault and battery upon another frail sister, named Eliza Smith, and were declared not guilty, and ordered to pay the court."35, 36, 37

Madame Elizabeth Randolph an entrepreneurial brothel owner bought a lot of land at the intersection of Park and Clay Streets where she had erected a three story brick dwelling and opened it as an upscale parlor house. Brothel owners such as Randolph were well known to the police. In 1842 the Whip, a short lived but celebrated male weekly included in visit to Baltimore, a description of Park Street and Eliza Randolph’s house which they wrote “has about a dozen girls, in all sizes, shapes and ages.” The authors then went on to state “in Park Street there were a dozen houses of the lowest order.” In 1845 fourteen madams, were charged with “keeping a bawdy house.” All were fined but quickly resumed operations. Mary Bushrod and Matilda Oliver may have worked for Elizabeth Randolph. Both women were charged with robbing “an old gentleman” who was “sojourning” on Park Street and were each fined $55.00.38

33 The Baltimore Sun (Baltimore, Maryland), 7 May 1840, p. 2, for assault, and 8 October 1841, p. 2, "Murderer of John Bigham arrested, Frederick Konig, alias Boss Konig."

34 The Baltimore Sun 29 January 1847, p.2., "A Hard Party " Boss Konig" and other "Blood Tubs" broke up the house of Sophia Cook in Caroline Street and fought the police called into quiet the scene. All were arrested. "While in the watch house they made an attempted escape but were later caught and rearrested."

35 The Baltimore Sun (Baltimore, Maryland), 13 February 1845, p.1, State vs Polly Bushrod and Francis Turner. Polly was indicted aiding in a robbery and possessing a stolen watch. She later testified she was drunk at the time and had no real knowledge of the transaction. A jury trial resulted in a not guilty verdict.

36 The Baltimore Sun (Baltimore, Maryland) 26 September 1843, p. 2. "Polly Bushrod charged with beating Miss Clara Powell" and 17 June 1845, p.2., Matilda Oliver and Polly Bushrod "indicted for robbery at a house of ill fame."

37 Baltimore Daily Commercial (Baltimore, Maryland) , 25 May 1846, p. 2. Baltimore City Court, Matilda Oliver (colored) and Mary Bushrod "nymphs of the pave" charged with assault and battery.

38 The Baltimore Sun (Baltimore, Maryland), 16 June 1845, p. 2. Robbery. An old gentleman paid a visit the other day to Park Street and while sojourning in those parts he was robbed of $ 55.00. Officers Ridgely and Cook arrested and charged them both with the offense. They were later committed to jail.Crime, Gangs, and Violence

In the year 1846, at least four other murders were the result of stabbing the victim with a knife or dirk.39 In the 1840’s handguns were still relatively expensive and most murders victims were beaten, bludgeon or stabbed. Homicide by gun became more prevalent in the 1850’s.40 Alcohol played a large role in fueling the violence with the consumption of hard spirits peaked at over five gallons per person in the early 1800s as contrasted with approximately two gallons in 1970. A significant drop occurred in the 1840s and the rate stayed around two gallons going forward.41

39 Baltimore Daily Commercial (Baltimore, Maryland) 29 May 1846, p.1, Murder of Shadrack Woodling, 11 June 1846, Murder of John W. Ledum, The Baltimore Sun (Baltimore, Maryland) 24 April 1846, “State vs John Flynn”, The Baltimore Sun (Baltimore, Maryland) 28 March 1846, “Trial of Albert J. Tirrell”.

40 Melton, Ibid, p. 403.

41 Rorabaugh, W. J., The Alcoholic Republic an American Tradition (Oxford University Press: New York, 1979), pp. 8-9.

In Baltimore wage labor and slavery often converged. Enslaved worker Frederick Douglas wrote how he would circulate from employer to employer albeit at a rate that would not guarantee subsistence to a man with aspirations of a family.42 Workplaces like Baltimore’s many caulking and ship repair facilities were a mix of black and white workers. In his famed autobiography Frederick Douglas observed this unequal economic competition fueled racism and violence. He noted, “The conflict of slavery with the interests of the white mechanics and laborers” was a driving force.43 Modern historians agree that many violent incidents were sparked by these two factors. They also note Baltimore’s burgeoning population, crowded living conditions, and the increased competition for jobs especially in shipbuilding and manufacturing.44 By 1830, over one-third of the state’s free black people lived in Baltimore. In the city free blacks could find work and educational opportunities largely unavailable elsewhere in Maryland. New arrivals from the Eastern Shore and Southern Maryland joined the existing community of black churches and social groups and helped them grow in both size and influence. Baltimore offered free and enslaved men and women the opportunity to earn wages—wages that often went to purchase their own freedom or the freedom of family members. Historian Seth Rockman explained, “When slaves gained some control over the wages they earned, freedom was typically not far behind.”45

42 Rockman, Seth, Wage Labor and Survival in Early Boston (The Johns Hopkins Press, Baltimore, 2009) p. 246

43 Douglas, Frederick, Narrative of Frederick Douglas as American Slave Written by Himself, (1845; repr., Boston, Bedford Books, 2003), pp. 106-109, Douglas Frederick, Autobiographies, My Bondage and My Freedom, ed. Henry Louis Gates Jr., (The Library of America: New York 1994), p. 330.

44 Towers, Frank. “Job Busting at Baltimore Shipyards: Racial Violence in the Civil War-Era South” The Journal of Southern History, volume 66, no. 2, 2000, pp. 221–256, JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/2587658 Accessed 15 October 2020.

45 Rockman, Seth, Scraping by: Wage Labor, Slavery, and Survival in Early Baltimore (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2010), pp. 10, 65.

The Penny Press

“Ever vigilant, ever active, they seek out crime even in dark hiding place…”

Beginning in the 1830’s Baltimore’s literate working class, could purchase The Baltimore Sun for a penny. From the 1830s onwards the mass production of inexpensive newspapers became possible following the shift from hand-crafted to steam-powered printing. The recently founded local newspaper The Sun sets technological advancement with use of Samuel F.B. Morse's new telegraph machine and wire lines to carry dispatches and news from events of the distant Mexican-American War. Baltimore regiments participate in the campaigns and their actions quickly reported back to city's citizens and relatives. In these pages some of the most popular features were crime news that provided sensational and titillating stories full of direct quotes which incorporate everyday speech.46 Thanks to the rise in newspaper circulation, Baltimore street gangs by 1845 were known nationally. The Sun’s, first publisher, Benjamin Day (1810-1889), wrote, “The penny press has however changed the aspect of affairs in this respect. Ever vigilant, ever active, they seek out crime even in dark hiding places, drag it into the light, but for it many crimes would go unpublished."47

The 1836 murder of New York City prostitute Helen Jewett was the first real American crime case to receive in depth press in James Gordon Bennett’s, New York Herald. Bennett introduced the practices of observation and interviewing to provide stories with more vivid details The Herald and other papers reports of the sensational crime and subsequent trial excited the public and changed the way American journalism covered sex and scandal; two subjects previously nonexistent. Public interest in extraordinary crime was further heightened in 1841 with Edgar Allan Poe’s, “The Murders in the Rue Morgue”. In 1842 Poe’s sequel, to the Rue Morgue, The Mystery of Marie Rogêt became the first murder mystery based on the details of a real crime, the 1841 murder of Mary Cecilia Rogers. The Rodgers case, much publicized by the press, also emphasized the ineptitude and corruption of New York City’s watchmen system of law enforcement.

46 Burrows, Edwin G., Wallace, Mike, A History of New York City to 1898 (Oxford University Press, New York, 1999), pp. 524-525. The popular press begins in New York City with The Sun Herald. The Baltimore Sun quickly adopted a similar format and some of the same features.

47 The Baltimore Sun (Baltimore, Maryland) 21 April 1840, p. 2.

Other sources:

Cohen, Cline Patricia, The Murder of Helen Jewett (Vantage Books, New York, 1998), pp. 24-25

Stashower, Daniel, The Beautiful Cigar Girl, Mary Rodgers, Edgar Allan Poe and the Invention of Murder (Dutton, New York, 2006), pp.99-99

Meyers, Jeffrey, Edgar Allan Poe: His Life and Legacy (New York, Cooper Square Press, 1992)

Lardner, James, Reppetto, Thomas NYPD: A City and Its Police (New York, Owl Book, 2000) pp. 18–21.

The Sun’s reporters regularly attended trials in the City Court, Day made sure stories of misdeeds and infamy were in all Baltimore Sun issues, for they were a constant source of sales. He knew instinctively stories about Baltimore’s flamboyant street gangs such as the “Gumballs”, “Rollers” and “Blood Tubs” sold newspapers. These narratives were dramatic and filled with graphic descriptions for the eager readers they represented and the real dangers faced by the citizens of Baltimore in the 1840’s and 1850’s.48 In their pages readers could identify with the victims and be reassured of the criminals' capture and punishment.49 Street gangs were first formed in the early ninetieth century but became more formally organized in the 1830's.50 The gangs quickly developed connections with politicians from opposing political parties in the 1830's. Gang activities frequently appeared in the local newspapers, along with vivid images of stabbing and shootings.51 Positive mentions of the exploits of the constables and the firm of Zell, Ridgley and Cook appeared regularly and suggest both organizations maintained cordial relations with the press.

48 The Evening Post (New York, New York), 23 September 1845, p. 1., "In Baltimore ... assumed nicknames pertain to certain association of "nice young men" there are the –“Rollers, Gumballs, Cock Robins, Grizzly Bears, Will Fights, Greasy Pigs, Butt Enders, Sandy Bottoms, Never Sweats, Screw Balls, Rangers, Blue Dicks, Canton Rackers, Tormentors, Blood Tubs, Arabs, Skin Flints, Blue Bumpers, Saddle Horses, Hard Fisters, Cut Headers and Single Combatants and besides others too numerous to count.”

49 True Crimes: An American Anthology editor Harold Schechter (The Library of America, New York, 2008), xiii.

50 Melton, Ibid., pp. 14, 22.

51 The Baltimore Daily Commercial (Baltimore, Maryland) see 4 January 1845, p. 2, 11 July 1845, p. 218, and September 1845, p,.2.

This 1840's daguerreotype shows an unidentified young fireman of the Baltimore Vigilant Fire Company.

The fireman wears a red shirt, hard helmet and is carrying a speaking trumpet.

Library of Congress collection.In 1843 The Baltimore Sun warned its readers that the gangs associated with the cities volunteer fire companies were a menace. The remedy proposed by the Sun, was, “the exclusion of all boys from membership in fire companies. Under such principles we should hear no more of the "Gumballs", "the Cock Robbins"," The Rollers", " the Screw bolts", the "Never-sweats" and other similar low-life associations of the wild and reckless youths who glory in the strange designations we have quoted here".52 The danger often began just prior to city elections where voters would collect highly-visible, labeled voting tickets for a candidate, stand in line, and give their tickets to a ballot officer at their local polling place. Often it was impossible to figure out who had voted when or where, and some candidates hired gang members as voting marshals to oversee elections. The phenomenon was so rampant that some biographers of Edgar Allan Poe ascribe his death to a cooping incident during a Baltimore election confirmed.53

52 The Baltimore Sun (Baltimore, Maryland) 29 May 1843, p. 2.

53 Zarrelli, Natalie, Election Fraud in the 1800’s involved Kidnapping and Forced Drinking. How roving “cooping” gangs got voters drunk and disturbed the democratic process. September 2016, Atlas Obscura, https://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/election-fraud-in-the-1800s-involved-kidnapping-and-forced-drinking accessed 22 October 2020.

The Baltimore Police Constables

Baltimore in 1846, like many American cities, was poorly policed and, with a reputation for corruption, its citizens had a strong distrust of authority. Those with a crime to report had to contact one of the city’s 14 police constables or a watchman charged with keeping lookout over their particular ward.54 The constables were at best a rudimentary force, and sometimes referred to as “night watchmen” they neither wore a uniform nor received training. Their duties included calling the hours, lighting street lamps and helping to quell disturbances. They were all political appointees, beholden to the mayor who nominated them yearly based on their political support.55 They were selected largely on party affiliation; many of the city’s most violent gang members served on the police force as constables.56

54 The Baltimore Sun (Baltimore, Maryland), 10 March 1845, p. 2., “list of city police and residence, plus extra police"

55 Melton, Ibid., p. 52.

56 Melton, Ibid., p. 44.

Police constables despite their name were not police officers in the modern sense, for they had limited authority and were rarely armed with more than a truncheon. In one notorious 1843 incident, three constables were tried for cowardice for refusing to aid a fellow officer, and all were dismissed from the force.57 In the 1840’s being a constable was dangerous work. They were often called to fights and brawls and attacked with impunity. For example, in 1844 a watchman who attempted to apprehend a suspect was beaten to death with a spittoon.58 Pursuit of serious crime, murder, theft and arson were typically given over to private security firms such as that of Zell, Ridgley and Cook.59 Zell, Ridgley and Cook increased their access to power in 1840 when a former partner of the firm, Jacob Cook, was appointed Deputy High Constable of the Baltimore Police.60

57 The Baltimore Sun (Baltimore, Maryland), 26 July 1843, p. 2, Reported the trial of three watchmen McCubbin, Hagan and Jacobs of the Western District for cowardice.

58 Baltimore Daily Commercial (Baltimore, Maryland), 27 November 1844, p.1, “Trial for the murder of Watchman Alexander McIntosh."

59 Machett’s Baltimore Directory for 1845, http://aomol.msa.maryland.gov/html/officials.html

60 The Baltimore Sun, (Baltimore, Maryland), 14 Nov 1840, p. 2, "Municipal Appointment Jacob Cook late of the firm of Cook, Zell and Ridgely has been appointed Deputy High Constable."

The Baltimore Police Department was established in its current form (with uniforms and firearms) in 1853 by the Maryland state legislature "to provide for a better security for life and property in the City of Baltimore". The state, however, did not give the city the power to run its own police affairs. In the early decades the department of police was marked by internal political conflict over split loyalties.61

61 Lewis, H. H. Walker (Summer 1966), "The Baltimore Police Case of 1860", Maryland Law Review, XXVI (3), Accessed 21 October 2020

The population of Baltimore in 1840 was 102,313 inhabitants and the Baltimore constabulary was vastly understaffed and the constables were vastly outnumbered. That aside, the constables were poorly paid and beholden for their positions to the patronage of the party in power, hence often unwilling or unable to investigate serious crime. For crimes that drew public attention and outrage or were the subject of features in the Baltimore Sun, like the murder of Leplat Carter, often prompted the mayor to offer rewards and bring in private firms. Such firms in return for a substantial reward would use their resources to capture the accused. Zell and Ridgley were almost always armed and were ready to use weapons to apprehend a suspect. Such was the case on 18 November 1847 when newspapers across the country announced the arrest of Lewis Cummings for the murder of Leplat Carter. “For a long time until very recently he eluded the most diligent efforts of our police, but at length it seems those most energetic officers, Messrs. Zell and Ridgley got a clue to his whereabouts and ascertained beyond a doubt the identity of the seaman passing as Henry Adams on board the sloop of war Decatur was Lewis Cummings.”62

62 The Charleston Daily Courier (Charleston, South Carolina), 18 November 1847, p. 2.” Arrest of Lewis Cummings charged with murder of Leplat Carter.” …, Messrs Zell and Ridgley got a clue to his whereabouts and ascertained beyond a doubt the identity of the seaman passing as Henry Adams on board the sloop Delaware was Lewis Cummings”.

The Escape of Lewis Cummings

Attentive news readers would later learn Lewis Cummings had quickly fled Baltimore with the help of his friends: “It is stated on good authority that Cummings was seen on the afternoon of the of the murder in a leather top carry all, in company with several other persons driving out the Madison Street at a rapid gait; and is currently reported that the horse which was used on the occasion, died from over-driving the same night.”63 Cummings destination was New York City where he “shipped” (enlisted) on 14 February 1847 aboard the sloop of war, USS Decatur under the name Henry Adams.64 Like many a recruit on the run, Cummings' reasons for enlisting in the Navy included escape, regular food, and shelter, the lure of advance pay and the anonymity of naval life and a new name could provide. After seven months on the run, Cummings boarded the USS Decatur, a vessel bound for the war in Mexico. As the ship left New York he must have felt secure. In addition like all new recruits, once on board, he was outfitted with naval uniforms, underwear, a pea-jacket, a mattress and two blankets, the cost of which was deducted from their future pay at regular intervals.65

63 The Baltimore Sun (Baltimore, Maryland), 8 July 1846, p. 2.

64 New York Daily Herald (New York, New York), 15 November 1847, p. 2.

65 Sharp, John G M., USN Civil War Enlistments, Boston, July 1863 http://www.usgwarchives.net/va/portsmouth/shipyard/enlisboston1863.html accessed 31 October 2020

USS Decatur

Cummings enlistment in the U.S. Navy under a different name was a commonplace occurrence; all enlistees were asked to state their name and age. In nineteenth century America searches for a criminal record and background checks were simply not possible. While some brief physical descriptions are occasionally noted on initial medical exams, nothing like this exists for the USS Decatur. Since he had no seagoing experience upon his signing the article of enlistment, Cummings was rated on 14 February 1847 as a Landsman. Landsman was the lowest rank of the United States Navy in the ninetieth and early twentieth centuries; this rank was given to new recruits like Cummings with little or no naval experience at sea and with no maritime training. As a Landsman, Cummings was assigned menial, unskilled work.66 Like many new recruits he would have found discipline aboard the USS Decatur strict and irksome but would have found that those who disobeyed an officer or boatswain were subject to summary corporal punishment with a boatswain’s starter or a flogging.67

66 Dana, Richard Henry, The Seaman's Friend: Containing a Treatise on Practical Seamanship, with Plates; A Dictionary of Sea Terms; Customs and Usages of the Merchant Service; Laws Relating to the Practical Duties of Master and Mariners. (Thomas Groom: Boston 1851)

67 Sharp, John G.M. The Ship Log of the frigate USS United States 1843 - 1844 and Herman Melville Ordinary Seaman 2019, pp 3-4 accessed 18 October 2020 2020 http://www.usgwarchives.net/va/portsmouth/shipyard/usunitedstates-hmelville

The Decatur sailed from Hampton Roads, Virginia, 1 March 1847, and after a brief stay at the Pensacola Navy Yard arrived off Castle Juan de Uloa, Mexico, 14 April, for duty in the Mexican-American War. Fourteen of her officers and 118 men accompanied Commodore Matthew C. Perry's expedition to attack Tuxpan. The USS Decatur also furnished 8 officers and 104 men for the capture of Tabasco from June 14-16. The Decatur had a crew of about 150 officers and men and during his ten months as a sailor the likelihood Cummings was part of one or both of these actions is high. Following these engagements, the Decatur continued to cruise in Mexican waters until 2 September when she sailed for Boston, Massachusetts, arriving 12 November 1847. John Zell met the vessel on arrival in Boston with an affidavit for the arrest of one, Lewis Cummings, aka John Adams, signed by the District Attorney, which after review by the commanding officer, Cummings was delivered and charged with murder. He was then taken by steamboat to Baltimore, where on arrival he delivered Cummings into police custody to be held in Baltimore jail until trial.

On Tuesday morning 8 February 1848, residents learned that in the central Baltimore City Court the case of the State vs. Lewis Cummings had begun. The court room was thronged with spectators, many friends of Lewis Cumming who pleaded “not guilty.” At the trial Cummings defense was represented by the firm of John Nelson and Charles H. Pitts, both well know attorneys.

The first witness for the prosecution was the Mayor of Baltimore, Jacob G. Davies. Davis gave dramatic testimony. Davies testified that he had seen a crowd on the corner of Park and Clay Streets, in downtown Baltimore. He then told the court he heard there “was a spree there” and that he “saw a man pursued by a woman; saw him stop to pick up a brick and spoke to him and told him he ought to be ashamed to throw at a woman; on turning to proceed he saw a man standing on the pavement exclaiming, “I am stabbed”. I asked who stabbed him and he pointed to a man who stood with a Spanish knife clasped in his hand with his hand raised up…” Mayor Davies subsequently identified that man as Lewis Cummings.

The trial record also noted four young people: William Thompson, Mary Bushrod, Matilda Oliver and Frederick Koenig were all arrested as accessories to murder but later released. The Baltimore Sun reported how the dispute between Cummings and the victim began. “It appear that a difficulty had taken place between a woman named Mary Bushrod and Thompson, when Cummings who was on terms of intimacy with the woman came up and assaulted Thompson who was very drunk.

During his testimony John Zell testified that Lewis Cummings had told him, “that all the difficulties he had been brought into through Polly Bushrod who would get into trouble and send for him…”68 Other witnesses stated Carter was said to have immediately stepped across the street and placing his hand on Cummings shoulder told him not to injure Thompson.” Yet another witness stated Cummings “was very drunk and appeared in a terrible rage.” A local physician Dr. Jamison testified that he had “attempted to render aide when Carter was brought into his office in a very exhausted condition caused by a wound in the breast, but that he was past surgical aide and expired.”6968 The Baltimore Sun, (Baltimore, Maryland) 9 February 1848, p. 1.

69 Baltimore Daily Commercial, Baltimore Maryland, 6 July 1846, p. 2.

Cummings and compatriots were all from working class backgrounds and in newspaper accounts are depicted as “roughs.” A rough was the 1840’s slang “for men who were ready to fight in any way or shape.”70 As the trial progressed several witnesses described Cummings as drunk, loud and aggressive. In his own defense Cumming testified that he had no recollection of stabbing Carter, that he was drunk and that he and Carter were friends.

70 This and other slang terms, appeared in Vocabulum; or, The Rogue’s Lexicon, an 1859 dictionary of criminal cant by George Washington Matsell, Matsell was the former chief of police for New York City see, http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/52320

The Jury Verdict

Later that afternoon the jury having quickly made up their minds rendered a verdict. The Baltimore Sun related the twelve jurors, had voted for second degree murder with a recommendation for mercy. This jury recommendation apparently was based on testimony regarding Cummings faithful service in the Mexican American War at the naval actions of Vera Cruz and Alvarde. In doing so they may have given credence to John Zell’s testimony “on leaving the USS Decatur Cummings had received a certificate from the officers for his good behavior and that the officers of the Decatur spoke of Cummings “conduct in high terms.”7171 New York Daily Herald, (New York, New York), 10 February 1848, p. 4 Baltimore jury recommended mercy based on Cummings service in Mexican American War.

Governor of Maryland Phillip Thomas (1848-1851), however, after hearing various efforts to induce him to exercise clemency decided to sentence Cummings to the penitentiary until the 2 April 1851, being a term of three years. Governor Thomas probably was informed of Cummings extensive criminal record and previous conviction for manslaughter. In the end, despite Cummings plea for mercy, Thomas declined to pardon him for he found Cummings acknowledgment that he was intoxicated and had no intent to murder Carter was offset by the very nature of the crime characterized in The Baltimore Sun as “a wanton homicide.”72

72 The Baltimore Sun (Baltimore, Maryland), 6 March 1848, p. 2.

On 4 February 1850 Governor Thomas pardoned Lewis Cummings who had served two years of his three year sentence.

* * * * * * * * * *

Murder –The Baltimore Sun, (Baltimore, Maryland), 04 July 1846, p.4

Our city on Saturday afternoon was the scene of a disgraceful affray, which resulted in the death of a young man about 19 years of age named Leplat Carter. As we learned, a disturbance and fight occurred about two o’clock in Park Street near Clay between a man named William Thompson and woman named Polly Bushrod, during which a man named Lewis Cummings interfered and he and Thompson seized each other. Cumming drew a dirk knife and threatened to use it, but he was prevented by Carter, who as a mutual friend knowing both the parties interfered. Thompson got clear of Cummings, leaving Carter with him. It is not distinctly known what took place between the two, but Cummings was seen to raise the knife and drive it downwards into Carter’s left shoulder, passing through the collar bone and clear through the left lung and cutting a large artery. The deceased ran a short distance and fell and died. Drs. Tilghman and Jameson were in immediate attendance upon him but could do nothing for him. Coroner Bowman rendered a verdict in accordance with the facts. The murderer succeeded in effecting his escape, and has not yet been arrested. His Honor the Mayor, endeavoring to quiet the disturbance, and was there at the time of the murder, but his presence failed to arrest the design of the murderer. The police have been constant in their efforts to arrest him and it is to be hoped they will be successful.

Arrested _ William Thompson charged with being accessory to the murder of Leplat Carter, alias Life Carter, was arrested by officers Moone and committed to the jail by Justice Egerton for further hearing. Mary Bushrod, Matilda Oliver and Frederick Konig, were arrested by officers Myer and Gross, and held to bail by Justice Egerton to appear at court and testify in the above case.

“Another Murder,” Baltimore Daily Commercial, Baltimore Maryland, 6 July 1846, p. 2.

We are called upon again to record one of those unfortunate affairs which sometime occur in a community by which one has lost his life and another probably forfeits his to the laws of his country. A party of young men consisting of Louis Cummings, Leplat, alias, “Life” Carter, Wm. Thompson, alias, “ Country”, and others congregated in and about the neighborhood of Park and Clay Streets on Saturday afternoon between 3 and 4 o’clock drinking, carousing, &c when Carter was stabbed by Cummings in the left shoulder causing his death in a few moments afterwards. It appear that a difficulty had taken place between a woman, named Mary Bushrod and Thompson, when Cummings who was on terms of intimacy with the woman came up and assaulted Thompson who was very drunk. Carter immediately stepped across the street and placing his hand on Cummings shoulder told him not to injure Thompson, that he was drunk and could not help himself. Cummings instantly turned around and drawing a long bladed Bowie knife which he always carried on his person replied “die you son of a ----------“and struck Carter on the left shoulder a tremendous down blow, the blade of the knife entering the lungs and passing very near his heart, cutting the large blood vessels and making it a frightful and mortal wound.

He drew the knife out and ran into Elizabeth Hunts’ house on the corner of Park and Clay Street and Carter sank down on the pavement dying in seven or eight minutes. Col. Davies who happened to be in the vicinity nearby called on some persons nearby who assisted Carter into the office of Dr. Jameson in Lexington between Park and Howard Street, but it was too late to save his life. Cumming in the meantime got out of the house and fled and has not been heard of, although the police are straining every nerve to find his hiding place. Coroner Bowman was sent for and held an inquest at Dr. Jameson's office, where a post mortem examination was held by Dr. Jameson, assisted by several other physicians. The jury rendered a verdict in accordance with the facts. Carter was a young man not quite 20 years of age, Cumming is about age 30. A partial examination of the affair was held by Justice C. C. Egerton senior, at the Central Police Office, which resulted in Thompson being committed for further examination on the charge of being concerned in Carter’s death. Mary Bushrod, Matilda Oliver and Frederick Koenig who are witnesses to the whole transaction were held on bail to appear and testify in the case. We learn that the Mayor has offered $500.00 for the arrest of Cummings.* * * * * * * * * *

Still at Large

No traces have yet been obtained of Louis Cummings, the murderer of Leplat Carter on the afternoon of the 4th instant. Captain Gifford, the High Constable, and officer Moon have returned from an excursion to Philadelphia, but their expedition and exertions proved unsuccessful in learning anything of his probable whereabouts. It is stated on good authority that Cummings was seen on the afternoon of the of the murder in a leather top carry all, in company with several other persons driving out of Madison Street at a rapid gait; and is currently reported that the horse which was used on the occasion died from over-driving the same night. We would ask if there is not a law in this state which makes it a criminal offense to aid or abet criminals or fugitives from justice or arrest. Why is this law not enforced? The parties who aided in this case are known. Will the officers of justice see to it?

We have been furnished with the following description of the person Cummings which may assist in his capture. He is represented as 28 years of age, five feet eight or nine inches in height, and stout, nose slightly turned up – face rather round, and fully freckled and in conversation, has a loud strong voice and speaks positively There are believed marks of Indian ink on one of his arms. He wore a tweed frock coat and white hat with crape around it on the day of the murder. Generally wears his neck handkerchief very low exposing his neck. He has at all times a sullen look and in costume as well as general appearance represents pretty accurately what is termed “rowdy.”Source: The Baltimore Sun (Baltimore Maryland), 8 July 1846, p. 2.

* * * * * * * * * *

MAYOR’S OFICE

BALTIMORE July 6th 1846$300 REWARD Whereas a most foul and unprovoked murder was committed on the afternoon of the 4th instant, at or near the intersection of Clay and Park Streets upon the body of LEPLAT CARTER, I do hereby, by virtue of the authority in me vested offer a reward of THREE HUNDRE DOLLARS, for the apprehension and conviction of the murder or murders.

JACOB C. DAVIES, Mayor

Source, Baltimore Daily Commercial (Baltimore Maryland), 7 July 1847, p. 2.

Arrests - Officers Fulton, Gross and Barnard yesterday arrested George B.Martin and Jos Craig, charged with aiding and abetting in the escape of Lewis Cumming, the murderer of Leplat Carter on the 4th instant. They were committed to jail by Justice Kincaid for a further examination.

Source: The Baltimore Sun (Baltimore Maryland), 15 July 1846, p. 2.

* * * * * * * * * *

Navy Yard Pensacola

October 9th 1847Sir,

I have the honor to acknowledge the receipt of your communication of the 1st instant addressed to Commander Richard J. Pinckney which has been duly handed to that gentleman. I have the honor to enclose a communication from Commander Pinckney dated the 8th instant in reference to a man on board the Decatur charged with having committed a murder. Also a copy of a letter from Messrs. Zell & Ridgely, police officers of Baltimore dated Sept. 28th in relation to the same and reply.

As the ship is ordered to proceed to Boston I have directed Commander Pinckney to keep the man referred to on board informing him that he would receive instruction from you in reference to the disposal of the man on his arrival in Boston.I have the honor to be very respectfully your most obedient servant.

[Signed] W. K. LatimerTo: the Honorable J.Y. Mason

Secretary of the Navy, Washington DCSource; W.K. Latimer to J.Y.Mason, 9 October 1847, Letters Received by the Secretary of the Navy From Captains ("Captains' Letters") 1805-61; 1866-1885, 1 Sep 1847-31 Oct 1847, Volume 342, Letter Number 146, , RG260, M125, NARA DC with enclosures.

* * * * * * * * * *

Baltimore

28 Sept 1847Sir,

There was a murder committed in this city on 4th of July 1846 by a person named Louis Cummings, he murdered Leplat Carter, we have information that Cummings shipped on your vessels at Pensacola under the assumed name of Henry Adams. Cummings alias Adams as near as we can describe him is about 28 to 30 years old, healthy stout built, sandy hair and freckled face. Our object in writing is to ask that you will favor us with your attention in this matter and if the information we received be correct, that you will give us as early notice as possible when we will take the necessary steps to have him brought to trial. It will require the utmost security there is an indictment against him. We shall be pleased to hear from you at your earliest convenience.

Very respectfully yours

Zell & Ridgely

Police OfficersTo: Richard S. Pinckney

USS Decatur

PensacolaN. B. As well as we understand our informant, he must have shipped last winter.

* * * * * * * * * *

U.S. Ship Decatur

Pensacola

October 8th 1847

Gentlemen,

I respectfully forward a copy of a letter received from Messrs. Zell & Ridley police officers Baltimore, stating that a murder had been committed in Baltimore by a man named Cummings, but who had shipped under the name Henry Adams. I find that there is a man answering to that name given by him. I had him confined and would respectfully ask for further instructions. I am Sir very respectfully your most obedient servant.

Richard S. Pinckney

Commander USN

Note: On reverse, an order by the Secretary of the Navy,

“Pinckney’s letter and enclosure, on his arrival in Boston, if an affidavit which in the opinion of the District Attorney is sufficient, he will deliver up the man thus charged with murder without such an affidavit he will return to duty. The man cannot be kept in confinement on their request alone.” J. Y.M

Done, October 16th* * * * * * * * * *

Police Intelligence

Charge of Murder- Officer Zell of Baltimore, arrived in this city yesterday from Boston on the way to the former city, having in charge a sailor by the name of Louis Cumming, alias Henry Adams, on a change of stabbing a man by the name of Leplat Carter, with a knife, inflicting several wounds, causing almost immediate death. This murder it appears was committed in a street affray in Baltimore, on the 4th of July 1846, a year ago last July. The accused escaped at the time and shipped in the United States service, at Pensacola, since which time he has been at Vera Cruz with the squadron. The information having come to officer Zell that the accused was on board the U.S. Ship Decatur bound for Boston, the officer proceeded there, and on arrival of the ship, Cummings was taken into custody, and is now on his way to Baltimore for trial escorted by officers Stephens and Huthwaite of this city.

Source: New York Daily Herald (New York, New York), 15 November 1847, p. 2.

Arrest of Lewis Cummings, charged with the Murder of Leplat Carter,-

Our readers will remember probably the murder of a young man named Leplat Carter in street brawl upon the 4th of July 1846, together with the charge of the offense against Lewis Cummings, his flight from justice and the success with which he baffled the inquiry that was set on foot immediately after the occurrence. For a long time, indeed until very recently, he eluded the most diligent efforts of our police; but at length it seems those energetic officers, Messrs. Zell & Ridgely, got a clue to his whereabouts and ascertained beyond a doubt the identity of a seaman passing by the name Henry Adams on board the sloop of war Decatur, Lieutenant Pinckney commanding, in the Gulf Squadron with Lewis Cummings, the fugitive from justice. Upon the arrival of the Decatur, during the month of September at Pensacola, Mr. Zell communicated through the Secretary of the Navy with the commanding officer of the vessel and procured the arrest of Cummings, and his secured his detention on board; and the vessel being bound to Boston, Mr. Zell obtained from his Excellency Governor [Thomas] Pratt, [1845-1848] a few days since, a requisition upon Governor of Massachusetts, and proceed to Boston to await the arrival of the Decatur. On the 12th instant, last Friday, she entered the harbor and the prisoner was upon the application of Mr. Zell delivered into his custody. He left Boston with his charge on Friday evening and arrived in Baltimore by boat on Saturday night. Yesterday Cummings was brought before Justice Selby and committed to the jail to await his trial at the ensuing January term of the City Court.

Source: The Baltimore Sun, (Baltimore, Maryland), 15 November 1847, p. 2.

Conviction for murder –

The trial of Lewis Cummings for the murder of Leplat Carter in our court resulted this morning in a verdict of guilty of manslaughter, accompanied with a recommendation of the prisoner to mercy from the jury.

Source: The Washington Union (Washington, District of Columbia), 9 February 1848, p.3.

Sentence of Lewis Cummings -

After a sufficient delay which has been employed in an effort to induce Governor [Phillip] Thomas to exercise clemency in the case of Cummings convicted of the manslaughter of Leplat Carter, the court on Saturday sentenced him to the penitentiary until the 2nd of April 1851, being a term of three years. The Governor declined to pardon Cummings, unless the court would unite in the recommendation to mercy, which they very properly declined to do, for the act was a wanton homicide.

Source: The Baltimore Sun (Baltimore, Maryland), 6 March 1848, p. 2.

Pardon of Lewis Cummings –

We understand that Lewis Cummings convicted some two years ago, of the second degree murder, with the killing of a man on the 4th July some year or two years preceding, has been released from the penitentiary through the interposition of executive clemency.

Source: The Baltimore Sun (Baltimore, Maryland), 4 February 1850, p. 1.

* * * * * * * * * *

John "Jack" G. M. Sharp resides in Concord, California. He worked for the United States Navy for thirty years as a civilian personnel officer. Among his many assignments were positions in Berlin, Germany, where in 1989 he was in East Berlin, the day the infamous wall was opened. He later served as Human Resources Officer, South West Asia (Bahrain). He returned to the United States in 2001 and was on duty at the Naval District of Washington on 9/11. He has a lifelong interest in history and has written extensively on the Washington, Norfolk, and Pensacola Navy Yards, labor history and the history of African Americans. His previous books include African Americans in Slavery and Freedom on the Washington Navy Yard 1799 -1865, Morgan Hannah Press 2011. History of the Washington Navy Yard Civilian Workforce 1799-1962, 2004.

https://www.history.navy.mil/content/dam/nhhc/browse-by-topic/heritage/washington-navy-yard/pdfs/WNY_History.pdf

and the first complete transcription of the Diary of Michael Shiner Relating to the History of the Washington Navy Yard 1813-1869, 2007/2015 online:

https://www.history.navy.mil/research/library/online-reading-room/title-list-alphabetically/d/diary-of-michael-shiner.html

His most recent work includes Register of Patients at Naval Hospital Washington DC 1814 With The Names of American Wounded From The Battle of Bladensburg 2018,

https://www.history.navy.mil/research/library/online-reading-room/title-list-alphabetically/r/register-patients-naval-hospital-washington-dc-1814.html

The last three works were all published by the Naval History and Heritage Command. John served on active duty in the United States Navy, including Viet Nam service. He received his BA and MA in History from San Francisco State University. He can be reached at sharpjg@yahoo.com