SPECIAL TOPICS CONTRIBUTIONS BY JOHN G. SHARP

Women

in the Early Navy Yard - Seamstresses & Horse Cart Drivers, 1862-1867

Commodore John Cassin, 1760-1822

Josiah

Fox, Naval Architect, 1763–1847

* * * *

Women in the Early Navy Yard - Seamstresses & Horse Cart Drivers, 1862-1867

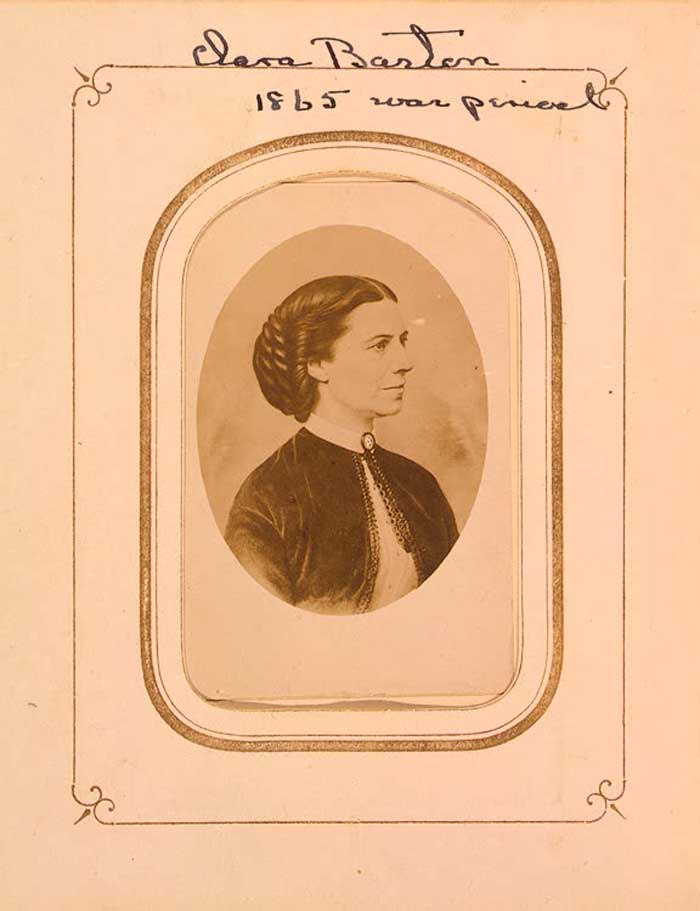

Historians, until recently, have largely overlooked the experiences of women who worked for the federal government during the Civil War era. In part this is because so few women worked for the government in the early years of the nineteenth century and most of the women were government clerks such as Clara Barton. Clara Barton who later went on to found the American Red Cross, first went to work in Washington, D.C. as copyist at the United States Patent Office in 1854. The Civil War, however, dramatically increased the demand for labor throughout the nation. The new Confederate government in Richmond, Virginia had to quickly overcome any reluctance and hire hundreds of women to fill its new departments and replace the men serving at the front.

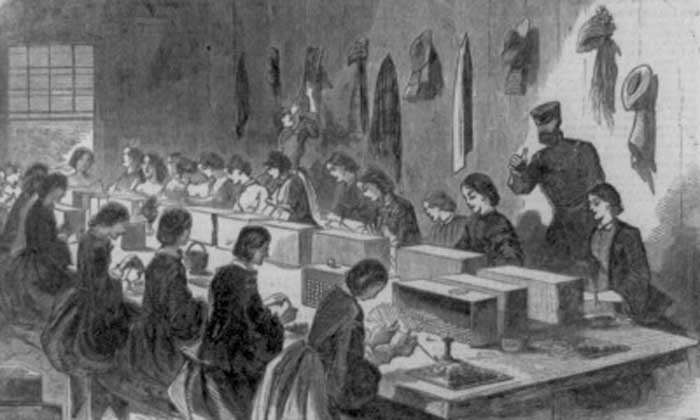

In Washington, D.C. during the war years, the Departments of the Treasury, Postal Department, and the Census Bureau began to employ women as clerks and currency counters. Modern scholars have largely concentrated on the better paying clerical positions mostly occupied by middle class women. The Department of the Navy, however, employed women as horse and cart drivers as early as 1819. The wartime requirements of naval munitions and ordnance manufacture created some new opportunities for working class women. Many of the armaments for the war were manufactured at the naval yards and army arsenals. The need to rapidly sew large quantities of canvass bags for these weapons and also to sew canvass awnings and flags for naval ships was a task that had normally been done by male sail makers. As a result of the wartime manpower shortage, the Navy decided to abandon tradition and employ young women like Annie Beck and Almira V. Brown in the ordnance laboratory for the first time. Many of these new employees were either related to mechanics and laborers of the naval yard, or like Brown, were widows of men killed during the war or on government service.

The history of nineteen century female employees within the naval shipyards, with one exception has received little attention. Historical records and documentation, while available, have remained difficult to access. One major obstacle is that only in the latter part of the twentieth century has the Department of the Navy, begun to systematically collect data on employee race and gender. Today the majority of early records are largely inaccessible for they reside in large old style payroll ledgers, the greater parts of which are housed at the National Archives and Records Administration, Washington DC. These records for the most part, have never been transcribed or microfilmed. While researching what became History of the Washington Navy Yard Civilian Workforce 1799 -1962, I came across a November 1867 payroll record, with a listing of six women, employed as horse cart drivers. Intrigued, I searched to find other such records, and found a payroll record for "sewers" dated May 1862. These enumerate the names of women employed at the ordnance department laboratory. Most of these young women were paid about a $1.00 per day. The exact nature of their assigned duties is not stated, but from other records we learn they were employed at the naval yards to sew canvas bags used to store gun powder. These employees worked ten hours a day, six days a week. The women working at the naval ordnance laboratory were paid $1.00 per day which was a better than average wage. The work was viewed as patriotic but also dangerous, for there was the risk that a single errant spark might ignite the nearby gun powder or pyrotechnics lockers with catastrophic results. One example was the explosion and fire that killed twenty-one young women working at the U.S. Army Arsenal Washington D.C. on June 17, 1864.End Notes

1. Giesberg, Judith, Army At Home: Women and the Civil War on the Northern Home Front, University of North Carolina Press, 2009. Giesburg's superb history, is the exception, although she concentrates her study on the women employed at the various federal arsenals.

2. Oates, Stephen B., Clara Barton of Valor, Free Press: New York, 1995, p.11. Barton salary of $1,400. per annum while less than her male colleagues was far beyond the average wages of most women or men of the era.

3. McPherson, James M., Battle Cry of Freedom the Civil War Era, Oxford University Press: New York, 1988, p.449 and Frank, Lisa Frederich, Women in the American Civil War, Volume 2, ABC-CLIO, Inc., 2008, p.306. The Confederate government hired hundreds of women in the Treasury and other departments. The Confederate Treasury Department's "Treasury Girls" (1862 -1865), were responsible for signing Confederate Bank notes, see Frank, p 550.

4. Washington Navy Yard Payroll 1819-1820 , Betsey Howard is listed as Horse and Cart Driver, paid $1.54 per day the same rate as male drivers, see: http://www.history.navy.mil/library/online/wny_payroll1819-1820.htm

5. Marolda, Edward J., The Washington Navy Yard, An Illustrated History, Naval Historical Center: Government Printing Office, 1999,p. 61. Dr. Marolda was the first to document the career of Almira V. Brown, seamstress, first hired at WNY in 1864; retiring in 1920.

6. Sharp, John, History of the Washington Navy Yard Civilian Workforce 1799-1962 accessed on line: Naval Historical Center http://www.history.navy.mil/books/sharp/WNY_History.pdf.

7. National Archives and Records Administration, Records of the Bureau of Yards and Docks, Records Group 71 Washington Navy Yard Payroll, November, 1867.

8. Washington Star , 17 June 1864, Frightful Explosion at the Arsenal, :A large number of the female employees killed or frightfully wounded. 18 dead bodies taken out of the ruins already. At 10 minutes of 12 today a terrible catastrophe occurred at the Arsenal which has cast a gloom over the whole community, and rendered sad many a heart that was buoyant a few minutes previous. While 108 girls were at work in the main laboratory making cartridges for small arms, a quantity of fireworks, which had been placed on the outside of the building became ignited, and a piece of fuse flying into one of the rooms in which were seated about 29 young women set the cartridges on fire and caused an instantaneous explosion. The building in which the explosion took place is a one-story brick, divided off into four rooms and runs East and West. Those girls who were employed in the east rooms of the laboratory, mostly escaped by jumping from the windows and running through the doors pell mell; but those in the room fronting on the east, did not fare so well, and it is feared that nearly all of them were killed by the explosion or burnt to death:. Also see Washington Times, 17 May 2008 :Tragedy at the City's Washington Arsenal.COMMODORE JOHN CASSIN 1760 - 1822

Commodore John Cassin led the vital defense of Gosport Navy Yard during the War of 1812 and served as its Commandant during a formative era. John Cassin has been described by one distinguished naval historian as an "experienced and capable seaman" with "tested skills as manager and commander; a reliable officer." Cassin was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania on 7 July 1760, the son of Daniel Cassin an industrious Irish Catholic immigrant from Dublin. During the American Revolution at age 17, Cassin joined the Pennsylvania Militia as a private, where he participated in the Battle of Trenton. He was later appointed First Mate of Pennsylvania privateer schooner the "Mayflower" on June 27, 1782. His physical description as entered on the Mayflower's muster lists his as age 23 years, height 5 feet 10 inches tall, hair dark brown with a "fresh complexion." After the Revolution, Cassin continued on at sea as a merchant seaman, where he was twice shipwrecked. In the early 1780's Cassin married Ann Wilcox of Philadelphia; there the young couple had four children who reached adulthood, they were: Elizabeth Ann Cassin, Joseph Cassin, 1784 – 1821, Stephen Cassin1783 -1857 and John Cassin. Two of the couples sons, became naval officers, Joseph Cassin, a naval purser and Stephen Cassin, a hero of the war of 1812, was later appointed Commodore. Cassin's daughter, Elizabeth Ann Cassin, married naval officer Captain Joseph Tarbell who led in the repulse of British forces from Craney Island on 22 June 1813.

The establishment of the new federal navy created a need for experienced sea going officers and gave John Cassin his opportunity for he was directly appointed a lieutenant on 13 November 1799. In 1803 he was assigned one of his first important jobs as second officer at the Washington Navy Yard. The Secretary of the Navy, Robert Smith in his letter appointing Cassin stated his responsibilities for the administration of the navy yard. Smith's letter provides valuable insight as to duties and responsibilities of a naval officer at an early federal shipyard.

The public property at this place belonging to the Navy Department, requires the superintendence of a vigilant, active, and intelligent and You will consider yourself hereby invested with the charge of all the Vessels that are or may hereafter be in ordinary at this place – also of all the sores and also public property now at the Navy Yard, or that may hereafter be deposited there expecting the Small Arms which are to be in charge of Col. Burrows. The stores now here, you will receive by inventory from Captain Tingey, upon which you will be charged and held accountable for their Expenditure. – You will give Receipts for all issues you make. –

It is expected that You will immediately take measures for cleansing each Ship, and for the putting her as for as your means will admit, in a state of preservation , and ready for service as far as their dismantled state will admit , and that You will adopt such a discipline as will keep them all in that state. – It is also expected that You as far as may be practicable, arrange all the different stores having the stores of each Vessels placed separately and distinctively that you will have all the cordage Sails, Water casks, Boats & completely overhauled and put into a state fit for service, and its further expected that you will from time to time communicate to me such improvements in the arrangements at the Yard, as your Experience may suggest.

To enable you to execute the duties of this appointment, You will have a Clerk under you and You are hereby invested with the Command of all Officers and Men now at the Yard or onboard the Ships, or that may hereafter be attached to either.

You are allowed the frigate United States and her furniture for your accommodation and you will receive for your services, the pay and rations allowed by Laws to a Master Commandment.

On 10 January 1804 Cassin was made superintendent of WNY; his appointment was to fill the vacancy created when Thomas Tingey declined the position. Tingey had refused over issues of his pay and benefits but was later reappointed. Tingey and Cassin were a good team though of differing temperaments, they got on well together and it was Cassin's systematic mind combined with Tingey's practical experience running a federal shipyard that allowed them to write the first regulations for the governance of naval shipyards. One of John Cassin's continuing concerns was the training and development of an officer cadre. He was particularly sensitive to that reality that officers stationed ashore be employed fully, that "they will avoid setting an evil example of idleness and inactivity. While at sea, sailing masters, boatswains, gunners, and carpenters, have all important duties to discharge". Cassin then wrote "officers on shore station needed to live on the ships in ordinary" and to ensure their vessels and the crews were inspected at least once a day and their ships be kept "clean and sweet" and most of all ready for sea. Cassin proposed that all these activities be placed under the direction and supervision of a "master of the yard." Cassin's recommendations which were accepted by Tingey led to the streamlining of the maintenance and repair of naval ships in ordinary. More importantly his ideas marked the real beginning of legislation to provide shipyard commandants and their deputies a permanent supervisory staff of salaried civilian employees. April 1806 Cassin was promoted to Master Commandant. Tingey and Cassin worked together for over ten years with no serious issues and Cassin‘s two son's Stephen a hero of the War of 1812 and Joseph a purser would later work with for Commodore Tingey as well.

On July 3, 1812 Cassin was promoted to Captain, then the highest rank in the United States Navy. At the beginning of the War of 1812, he led the United States Navy in the Delaware for the defense of Philadelphia. His competence there led to a new appointment on August 10, 1812 he was designated the new Commandant of Gosport Navy Yard., a position which he held until June 1, 1821. Cassin wrote to Secretary of the Navy Paul Hamilton, two weeks after his arrival, and described his new quarters and command as wanting in comfort and civilian mechanics.

"I have the honor to inform you of my arrival at this place on Sunday last, after a very disagreeable passage of ten days heavy gales & rainey weather and [I am ] extremely unwell, but by the assistance of Doctor Schooflield I am much better. I caught a violent cold in the river followed up by going into the house which is too Small entirely for my family and on the first night we had 18 inches of water in the cellar, when I was complel'd to partake of your liberal instructions as it respects my quarters by making two Small wings & kitchen to the House, my Office is too small and under the Hospital whenever they wash it the water runs all over me, books & everything. I find we are in want of everything to make it like a Navy Yard."

"We are much in want of a Master Blacksmith also a Plumber and Joiner. I should recommend John Bishop & Willm Saunders from King's Shop, also Nicholas Fitzpatrick Joiner, there is a very Smart man Boat builder who formerly worked under me at the Yard, which is now employed at Norfolk by piece work for the Navy, which I do not admire. I would beg leave to recommend him also should it meet your approbation to get me these workmen with the addition of a few Shops to be able to Save a good deal of outdoor work, all of which I have the honor to submit for your Consideration."

Cassin's arrival at Gosport came at exactly the right moment and a most critical juncture, for he helped lead the American defense against the British naval attack and assisted in the organization of the fifteen gun boat flotilla that took the offense and engaged and repulsed the Royal Marines, the 102nd Regiment and two Independents Companies of Foreigners (French mercenaries), plus the H.M. Frigate,Junion. After restoring order and security to his new command Cassin spent the next nine years endeavoring to build up the young naval yard and develop and train its officers and provide Gosport with a group of experienced master mechanics.

In June of 1821 he was chosen to be the Commanding Officer of the Southern Naval Squadron based at Charleston, South Carolina. As leader of naval squadron Cassin was accorded the honorary title Commodore. Despite his advancement and honors, his last years were hard for Cassin suffered terrible losses. In 1819 his younger son Joseph, a naval purser, died while on station aboard the frigate Porpoise, off Pensacola, Florida , his daughter Elizabeth Ann died on 23 November 1821 and his beloved wife and partner of forty years, Ann Wilcox Cassin died while he was at sea in 1821. Just shortly after his arrival in the city of Charleston to take up his new post, Commodore Cassin died on 24 March 1822. John Cassin was buried with full military honors at the cemetery of St Mary's of the Annunciation. In his obituary the Charleston Courier editor noted Cassin's long service to the nation despite lingering illness, and his goodness of heart and character led all who knew him to esteem him. While John Cassin never gained the heroic victories at sea enjoyed of some of contemporaries he served for two decades in a succession of critical shore assignments where the navy department knew they could always depend on his tested skills as an innovative manager and naval officer.

End Notes

1. McKee, Christopher A., Gentlemanly and Honorable Profession The creation of the U.S. Naval Officer Corps, 1794 -1815 Naval Institute Press: Annapolis, 1991, p. 188.

2. Ignatius, Martin and Griffin, Joseph, Catholics and the American Revolution, Volume 3, Philadelphia Pennsylvania, 1911, p.390.

3. Montgomery, Thomas Lynch editor, Pennsylvania Archives, Series 5, Harrisburg Publishing Company: Harrisburg, p.657.

4. Heidler,David Stephen and Heidler, Jeanne T editors, The Encyclopedia of the War of 1812, Naval Institute Press: Annapolis, 2004, p.130.

5. Naval Documents Related to the United States Wars with the Barbary Pirates Volume II Naval Operations including Diplomatic Background from January 1802 Through August 1803, editor Dudley W. Knox, Government Printing Office: Washington DC, 1940, p.388-389.

6. Smith to Cassin, 10 January 1804, The secretary stated his expectations: "All the workmen, laborers &c employed in the yard or repairing the Ships &c are to be employed under the direction and control of the Superintendent of the Yard, and to be paid for their services such compensation as may be agreed on with him." Naval Documents Related to the United States Wars with the Barbary Pirates Volume III, Naval Operations including Diplomatic Background from September 1803 Through March 1804, editor Dudley W. Knox, Government Printing Office: Washington DC, 1941, p.320-321.

7. Naval Documents, Volume III, p.392 -393.

8. Brown, Gordon S., The Captain Who Burned His Ships: Captain Thomas Tingey, USN, 1750-1829, Naval Institute Press: Annapolis, 2011, p. 53, 55, 59-60.

9. Nicholas Fitzpatrick had worked with John Cassin at the Washington Navy Yard and is enumerated on the payroll for July 1811 as a ship joiner, NARA RG 45. Fitzpatrick is also mentioned in a 15 April 1817 letter from Tingey to the Board of Navy Commissioners stating that Fitzpatrick and others came to the United States "at or under 8 years of age - having served all their youth to the trade and worked long in the yard - consider themselves citizens." John Bishop and William Saunders, both blacksmiths, had also worked with Cassin at Washington Navy Yard. The "King's Shop" reference is to Benjamin King, master blacksmith.

10. Dudley, William S. The Naval War of 1812 A Documentary History, Volume I, Washington DC: Government Printing Office, 1985, p.222-223.

11. Charleston Courier 24 March 1822.

12. McKee, p.188.

Josiah Fox, Naval Architect, 1763–1847

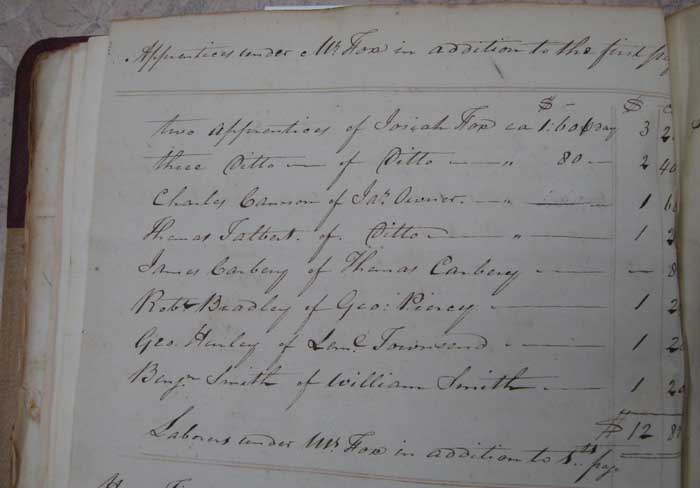

Josiah Fox early image and late photo. List of Fox's apprentices and their daily wage. Fox's correspondence, April 25, 1808.Josiah Fox became a noted American naval architect due to his extensive involvement in the design and management of the construction of the first significant naval warships at Gosport and Washington Navy Yards. Fox worked with his senior colleague Joshua Humphreys on the design of these ships. The ships Humphreys and Fox built helped lay the foundation for our Navy and ensured the new service had the nautical assets to fight successfully in the Quasi-War with France, the Barbary Pirates, and the War of 1812.

Josiah Fox was born in Falmouth, Cornwall, United Kingdom in 9 October 1763, into a large and relatively prosperous Quaker or Society of Friends family. Historically, the Friends have been known for their use of thee as an ordinary pronoun, refusal to participate in war, plain dress, refusal to swear oaths, and opposition to alcohol. While Josiah Fox wore plain dress, attended monthly meetings, and in general adhered to the Friends principles, he came into conflict with the group on a number of important matters of belief and practice. The conflict was such that Fox was formally disowned by the Friends Philadelphia Meeting for marrying a non-Quaker woman, and for "assisting in the building vessels of war." In later years, Fox's ownership of slaves and purchase of alcohol for his workers would also be questioned. Josiah Humphreys was similarly disowned by the Society of Friends for building ships of war.

Josiah Fox was born into a large family of thirteen children, nine of whom lived to maturity. His surviving siblings consisted of four older brothers and four sisters. His parents John and Rebecca Fox and brothers John and Henry all had maritime business connections. His brother John Fox was a successful merchant and importer and his brother Henry was a merchant ship captain for G.C. Fox & Company. Josiah may have attended the Friends School at Tiverton where he was instructed in religion, geography, French language, philosophy, and mathematics. In 1786 at the fairly late age of 23, Fox decided, despite some family objections, to pursue a career in shipbuilding. In a certificate dated 1787, Josiah Fox was described as being "of fair complexion, about five feet eleven inches, wearing brown hair and having a 'molde' on his left arm." Josiah began his apprenticeship at a private dockyard in Plymouth owned by master constructor Edward Sibrell. At Sibrell's yard he served for four years, learning his trade as shipwright, and in 1790 moved to the East India Dockyard in Deptford where he gained wider experience working on a variety of merchant ships. In 1791, through his family connections, Fox was able secure a billet on the merchant ship Crown for a voyage to the Russian city of Archangel. Archangel (Arkhangelsk) was the chief seaport of Russia. In Fox's day Archangel was still an important Baltic trading center for northern Europe. In November of 1791, he voyaged south, this time with his brother Captain Henry Fox on a year-long Mediterranean trading voyage to Venice and Cadiz Spain. In both his northern and southern voyages, Fox had time to experience and study a ship under sail and the opportunity to visit and learn from Russian, Italian and Spanish shipyards, and naval arsenals.On Fox's return to England, he became frustrated with the limited opportunities to make a name and career. In 1793 he traveled to the United States, at least nominally, to survey timber resources. In the States he was engaged to teach drafting to the sons of Jonathan Penrose, an American shipwright. In 1794 Josiah Fox married Elizabeth Miller 1768 -1841 at the Protestant Episcopal Church in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. The couple was very much in love and went on to have ten children with six surviving into maturity. While Fox's marriage was outside the Friends Meeting House and caused some tension within the Quaker community, it was generally well received.

Through the influence of his wealthy and politically well-connected uncle, Andrew Ellicott, Fox was employed on 16 July 1794 by the U.S. Navy as a draftsman working under naval constructor, Joshua Humphreys, designer of frigates. Fox was ambitious and aware that he was the only formally trained shipwright in the country and he thought himself fully qualified as a designer. In fact Fox's official position was that of War Department clerk, although his duties and responsibilities were primarily to complete designs and models for naval constructor Humphreys. Fox's career got off to rocky start with Humphreys by criticizing his designs, while Humphreys initially held Fox's skills as draftsman in high regard, he later accused Fox of drafting the models according "to his own opinion so foreign to my own." The older Humphreys became increasingly upset after Fox identified himself as a "Naval Constructor" and would only respond to Fox as "Mr. William Fox, Clerk of the Marine Department, War Office." Fox and Humphreys would continue to have a tumultuous relationship with significant disagreements over frigate design, the former believing that the vessels were too long and had too sharp a bow, among other problems. Their disagreement caused considerable animosity between the two men, with arguments over credit for the design continuing in the press as late as 1827.

Fox's initial annual compensation at the War Department was fixed at $500 per annum substantially above that of a shipwright:Mr. Josiah Fox

Sir,

You are hereby appointed a Clerk in the department of war, at the rate of Five hundred dollars per annum, to be appropriated at the present to the assistance of Joshua Humphreys who is constructing the models and draughts for the frigates to be built in the United States, and when that business shall be finished you will be directed to perform - your compensation to commission the 1st instant -Not long after his disagreement with Humphrey, Fox was transferred to Gosport Navy Yard. The old yard was in a state of disarray and largely quiescent. Gosport was a working Navy Yard during the American Revolution. The ragtag Navy created during the American Revolution was promptly dismantled after the war, and it wasn't until 1794 — in the face of threats to U.S. shipping from England, France, and the Barbary states of North Africa—that Congress authorized the construction of six frigates. Fox's assignment to Gosport Navy Yard was to design and oversee the building of the frigate Chesapeake and other vessels then under construction at the new yard. Fox proudly stated "during the whole of the period [at Gosport], he was employed in building and equipping that frigate, he had the sole charge of conducting the business, as no naval officer was assigned to that yard, which has been the only instance of the kind in the Navy Department." Much of this time Fox acted as the shipyard superintendent. The old Navy Yard when Fox arrived was suffering from years of neglect. During the Revolution the Gosport shipyard was under the auspices of the State of Virginia, but with the end of that war had fallen into disuse. Fox's was always an organizer and he quickly moved to draft regulations and to bring about greater economic efficiency and utilization of shipyard manpower. Like his predecessors, he employed slave labor extensively at Gosport and would later purchase slaves. The slaves Fox purchased were trained and employed at the shipyard with the profit from their labor going directly to him. As a consequence of his performance at Gosport, Fox's annual salary was raised to $750 per annum.

Writing to the Secretary of War Timothy Pickering, Fox stated: "The public Service Requiring the utmost Harmony should take place in the Naval Yard at Gosport (Virginia)" and went on to propose the first regulations for the governance of the Navy Yard. Fox's regulations were written to correct what he perceived as serious deficiencies. Fox wrote he was particularly concerned with the negligent manner the shipyard clerk Samuel Shore displayed while conducting public business, especially Shore's insufficient attention to supervising the workmen and meddling in Fox's affairs. Fox went on complain of the liberties management allowed Gosport workmen. Fox wrote that workers slept on the yard each evening and frequently quarreled. He later learned the reason laborers and mechanics slept at their workplace each night was that there were no rooming houses near enough to the ship yard, and what hotels or rooming houses that were available were so far away that the workers would have to have spent most of their day commuting. In the same letter, Fox went on to recommend that Gosport workmen be allowed their traditional rum ration. In 1798 Fox was appointed Master Constructor of the frigate Chesapeake, which was to be built in Norfolk. Fox apparently altered Humphreys design to his own liking, though this may have been partially the result of a timber shortage. That same year in February Josiah Fox became a naturalized citizen of the United States and later in the year his salary was raised by the War Department to $900.00. In 1798 the Department of the Navy was also created and, reacting to fears of French privateers seizing American merchant vessels, Congress authorized additional naval vessels and revenue cutters. In 1801, in response to budget reductions, Fox was laid off from his government position, but he continued to design vessels for the private sector.

In 1804, Secretary of the Navy Robert Smith sent for Fox to come to Washington, D.C., and convinced him to become the naval constructor at the Washington Navy Yard. At that Navy Yard Fox was to superintend the construction and repair of naval vessels. Commodore Thomas Tingey had overall charge of the yard and its employees. As naval constructor, however, Fox reported to the Secretary of the Navy and directed the largest and most skilled group of mechanics and laborers.

Thomas Tingey, like Fox, was born England but in the city of London in 1750. His family moved to the town of Lowestoft, a small North Sea fishing town, and he later served in the Royal Navy. In the early 1770's, Tingey moved to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and took service with merchant vessels in the Caribbean. Through successful trading ventures, he quickly became prosperous and decided to stake his future in new republic. In 1798, based on his Royal Navy and merchant experience, Tingey was appointed as a captain in the newly established federal navy. Fox's salary as constructor for the Washington Navy Yard was a generous $2000.00 per annum with $500.00 additional allowance for housing, and the liberty of taking as many apprentices as he chose, placing his total compensation on line with Commodore Tingey. Fox by 1807 had seven apprentices; five white, whose families paid him a commission to teach their sons the difficult and lucrative trade of shipbuilding, and two of his own slaves. In the early federal shipyards, all apprenticeships were signed indentures or private contracts between master mechanics and apprentice, but paid from public funds. All shipyard apprentices were paid a daily wage based on a percentage of the journeymen trade rate. The master mechanic typically signed and collected the apprentice's wages, passing this on to the apprentice or his parents after deducting an agreed tutorial fee. Slaveholders signed for a slave wage and made whatever provisions for the slaves support they deemed adequate.

At first the two men worked together; Fox's assignment to Washington coincided with the beginning of serious construction at the Navy Yard. Among his first assignments was the repair of badly deteriorating frigates in ordinary; many of these ships that had seen years of hard service. Fox also supervised the construction of numerous gun boats, designed for the naval actions in the Mediterranean. Fox designed seven of these first gun boats. The boats were actually built at various cities on the East Coast. But in April 1806 Congress authorized yet more gun boats and ten were built at Washington Navy Yard. These vessels were shallow draft boats, fifty to seventy feet in length, sloop or schooner rigged and armed with one or two guns. Fox compared them to Oyster boats, and questioned their utility. Most significantly during Fox's tenure, the yard built its first proper ship, the sloop of war Wasp and major repairs to the frigates United States, President and Essex.

Despite the Navy Yard progress in building and repairing vessels, Fox's relationship with Commodore Tingey deteriorated over time. As a military man, Tingey believed in discipline and deference to authority, and he was a firm believer in the chain of command. Fox on the other hand considered his appointment by the Secretary of the Navy sufficient to ignore yard policy when it suited. By 1806 each man was complaining to the Secretary about the other. Part of the problem was their differing personalities and a substantial part of their dilemma their confusing reporting relationships. Tingey had overall charge of the shipyard but Fox was hired by and reported directly to the Secretary of the Navy. One proof of the structural nature of the problem is that William Doughty, Fox's successor, experienced similar difficulties in his dealing with both Tingey and the next Commandant Isaac Hull caused by the overlap of their duties and responsibilities.

Tingey had always run the navy yard with a sense of noblesse oblige, allowing the master mechanics a great deal of authority and discretion and his workforce certain privileges that Fox found unwise. Fox wanted to organize his workers in companies so that there was a clear chain of command. From his writing it is clear Fox hoped to promote economy, control costs and discourage, the "too free use of Spirituous Liquors during the Hours of Work or the use of abusive language to any person whatever." Fox's caution regarding the use of "spirituous liquors" on the yard, was not simply that of a teetotaler, but reflects his genuine concern that alcohol was endangering workplace safety. In 1807 Commodore Tingey had also attempted to restrict alcohol usage which resulted in some of the workers complaining to the secretary of the navy.

Fox wanted to control waste and pilferage and urged his master mechanics to be "careful to prevent the Timber Materials and other of the Public property in the Timber Materials and other of the Public property in the Carpenters Department from being improperly expended, Wantonly destroyed, Wasted, Injured or pillaged - He will not permit any alteration whatever to be made in any part of the Ships whilst under repair without express orders being given for that purpose." Fox also cautioned his workers regarding the danger of fire. "He will take care that no Fires be made by the Carpenters and others attached to them to Bend their planks &c &c but at such places as may be deemed to be most proper for that careful purpose, and he is charged to see them all extinguished by Sunset."

Fox even went as far as to caution his employees to remember and have care for their environment and to avoid throwing debris in the Potomac and Anacostia River. Fox urged his men: "When working afloat he is not on any authority whatever to throw over board into the River any Stage Plank & Spalls, or other useful materials, neither is he to throw any rotten stuff that will sink to the injury of the river." Fox's proposed changes were never implemented, and it is unclear if Tingey ever saw them, but it is most unlikely that he would have approved them. Fox's management concerns with safety and the environment were in many ways profoundly modern. Tingey was more of a pragmatist, ever sensitive to issues of morale, and was reluctant to make too many changes as they might only increase the mechanics distrust. Commodore Tingey, like many of his workers, found Fox eccentric and difficult to understand.

One issue that caused considerable friction was Fox's training of two enslaved men, Edwin Jones and William Oakley, as shipwright apprentices. About 1804 Fox had purchased the two men and also purchased young Betty Doynes as a house servant. Many officers and senior civilians such as Commodore Thomas Tingey, Captain John Cassin, and senior clerks and master mechanics found that having the Navy hire their slaves a profitable and easy arrangement. During the first decade of the Navy Yard's existence, about one-third of the workforces were slaves. While some slaves worked as ship caulkers, a difficult and dirty job, most worked as laborers. Fox, however, had trained Edwin Jones and William Oakley as shipwrights, in the shipyard, an elite occupation. White mechanics apparently found Fox's training of blacks as shipwrights to be threatening to their sense of superiority and employment security.

Adding to the atmosphere of unease in 1807, Fox came to the defense of Peter Gardner, a master mast maker. Gardner, like Fox, had purchased a young slave, Davy Gardner, and trained him with his white mast maker apprentices. Gardner was later accused of taking small items without proper authorization which eventually led to his dismissal. Fox perceived the charges and dismissal of Gardner as a subterfuge and pretext for Tingey removing a supporter.

In June of 1807 the final break between the two men culminated with Tingey's appointment of William Smith, Assistant Foreman of Ship Carpenters, and John Petheridge, Foreman Afloat, ostensibly to aide Josiah Fox. Fox vehemently objected and stating Tingey's appointments were made with no consultation or notice. Fox particularly objected to Pethreridge's appointment as he was "frequently intoxicated."Fox asked for a board of inquiry and stated he would not work until some action was taken. "Finding that John Petherbridge is upheld in his Conduct, which I conceive is contrary to every principle of Justice, and the regulations of the Yard and that Richard Sommers, Shipwright, is ordered to be discharged for candidly as plain fact in my Inquiries; I have thought proper to withdraw myself from the Navy Yard until due inquiry should be made into the circumstances of the case and ample justice done me." In response Tingey wrote to the Secretary of the Navy stating that he would convene an inquiry into Fox's charges and take statements from all witnesses including Fox, under oath and Fox refused the inquiry.

Economic clouds were also on the horizon. Beginning in the Winter of 1807, the Embargo Act led to a tightening of the naval appropriations. In response, on 21 April 1808, Secretary of the Navy Robert Smith gave Commodore Thomas Tingey direction to reduce his workforce at the Washington Navy Yard. John Cassin, acting for Tingey, queried Fox as to the number of his employees and his proposed reductions. Fox replied on 25 April 1808, "If many of the frigates are to be equipped in the course of the present Summer that cannot be effected without a large force. . . .Where repairs are protracted to any length of time that decay already taken place will not only diffuse itself more intensively but by causing destruction to the furrowing timber, render repairs more difficult and expensive. It must be well known to you that some of our finest Frigates at this time are almost perishing for want of repairs and daily getting worse." Fox's response reflects his continuing concern for timely maintenance and the welfare of his employees. "I am compelled to say that I should think any reduction in the number of workmen at this time to retrench expenses impolitic (unless the appropriations are found insufficient for that purpose) and would therefore recommend that the work be pursued by the present number of workmen." Despite the merits of Fox's ideas, his perceived intransience and reluctance to be deferential to Tingey or understand his concerns proved his undoing.

At the beginning of the new administration of President James Madison, the new secretary of Navy Paul Hamilton, probably on Tingey's recommendation, "unceremoniously and perhaps unjustly" dismissed Fox. Hamilton again, probably at Tingey's bidding, directed that all of Fox's white apprentices be kept on the yard rolls if possible and the blacks dismissed.

After leaving government service, Fox manumitted his two enslaved apprentices Jones and Oakley and prospectively manumitted his house servant Betsey Doynes with an effective date of 1815. After examining his alternatives, Fox moved with his entire family west into Ohio territory where they settled. In Ohio Fox quickly became a highly successful landowner and businessman and leader in the Quaker community. The newly manumitted Jones and Oakley chose to accompany the Foxes west and remained in his employ as freemen for the next twenty five years. Sadly, Betsey Doynes died prior to her manumission.

In 1811 Fox and his family experienced the great New Madrid earthquake. This quake, the greatest ever in the United States shook the ground for months. The remainder of Fox's long life was less eventful. During the war of 1812, the frigates and other vessels Fox designed contributed to American naval victories. Ironically, Fox himself strongly disapproved of the war and thought it wholly unnecessary. Fox's beloved wife Anna died in 1841 at the age of 71. As he came to the end of his days, Fox's legacy as naval architect of such vessels as the Crescent, Congress, Philadelphia, Chesapeake, John Adams, Hornet and Wasp was secure. Modern historians may still debate the extent of Fox and or Humphrey's contribution to the overall design of American frigate but all recognize their achievement. Fox, in spite of those who "resented his independent Quaker ways, remained dedicated to serving the United States government to the best of his abilities." Fox died on 17 November 1847 at the age of 85 and was buried in the cemetery near the Concord Friends Meeting House, near Colerain Ohio.

Endnotes

1. Westlake, Merle, Josiah Fox 1763 -1847, Philadelphia: Xlibris 2003. Westlake's recent biography is the only work in print devoted to Josiah Fox's career as a naval architect and is particularly helpful for understanding Fox's early career in England, his extensive and important family relationships and his association with the Society of Friends or Quakers. See also Merle Westlake, Josiah Fox, Gentleman, Quaker, Shipbuilder, Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, Vol. 88, No.3 (Jul., 1964) pp. 316 -327.

2. Westlake, p. 43.

3. Westlake, 1964, p. 317.

4. Westlake, p. 30.

5. Toll, Ian W., Six Frigates, The Epic History of Founding of the U.S. Navy, W.W, Norton & Co:. New York, 2008, p. 54.

6. Toll, p. 52 -53.

7. War Department to Josiah Fox, 16 July 1794, NARA, Secretary of the Navy, Requisitions on the Treasurer, RG 45.

8. Westlake, 1964, p. 219.

9. Dickow, Chis, The Enduring Journey of the USS Chesapeake Navigating the Common History of Three Nations, The History Press, 2008, p. 26 -27.

10. Joshua Humphreys to Josiah Fox, 14 Oct 1794, National Archives and Records Administration (NARA), RG45, "I trust you will see to it…with the Negros they can procure "For Fox's ownership of slaves see, Dickow, p. 27. Westlake, p. 149.

11. Pickering to Josiah Fox, 12 May 1795, Peabody Essex Museum, Josiah Fox papers.

12. Pennock to Fox, 16 Nov 1795, Peabody Essex Museum, Josiah Fox papers.

13. Fox to Pickering, 24 Sept 1795, Peabody Essex Museum, Josiah Fox papers.

14. Westlake, p.46.

15. Hibben, Henry B., Navy-Yard, Washington, History from Organization 1799 to Present Day. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1890, p. 37.

16. Brown, Gordon S., The Captain Who Burned His Ships Captain Thomas Tingey, USN, 1750 -1829. Naval Institute Press: Annapolis, 2011. This superb biography of Thomas Tingey provides contains valuable new information regarding , the Washington Navy Yard work environment, Tingey's background and his dealings with Josiah Fox and other senior managers at the Washington Navy Yard. For Tingey's often troubled relationship with Fox, see p. 76 -78.

17. Westlake, p. 64.

18. Brown, p. 76- 77 and 108.

19. Brown, p. 141, for Doughty's relationship with Tingey and Maloney, Linda M., The Captain from Connecticut The Life and Naval Times of Isaac Hull, Northeastern University Press: Boston, 1986, p. 437 -438 for Doughty's relationship with Commodore Hull.

20. Rorabaugh, W. J., The Alcoholic Republic an American Tradition. Alcohol consumption peaked at over five gallons per person in the early 1800s as contrasted with approximately two gallons in 1970. A sharp drop occurred in the 1840s and the rate stayed around two gallons going forward. Data from the National Institutes of Health reflects current consumption rates peaked at only 2.7 gallons in the early 1980s and leveled off at 2.3 gallons in 2002. Even in our new millennium this early nineteenth century rate of 5 gallons per person still has the power startle modern readers.

21. Blacksmiths Petition to the Secretary of the Navy, 11 March 1807, NARA RG45 M125a.

22. Fox wrote a series of proto position descriptions in which he listed the duties and responsibilities of his construction department employees. He organized his thoughts very similarly to that used in job descriptions by the modern federal government. These documents are unsigned and undated but are in Fox's handwriting and archivist date them to circa 1804. NARA RG 45.

23. Liber X, no 23 Folio 279 & 280 filed in the District of Columbia Deed Books, District of Columbia Archives.

24. Tingey to Smith 12 June 1807.

25. Smith to Tingey 21 April 1808.

26. Fox to John Cassin 25 April 1808.

27. Brown, p. 78.

28. Hamilton to Tingey 10 August 1809.

29. Westlake, p. 89.

30. Toll, p. 473, makes the case for Humphreys while Westlake views Fox's contribution to frigate design as coequal.

31. Westlake, p. 147.* * * * * *

John G. “Jack” Sharp resides in Concord, California. He worked for the United States Navy for thirty years as a civilian personnel officer. Among his many assignments were positions in Berlin, Germany, where in 1989 he was in East Berlin, the day the infamous wall was opened. He later served as Human Resources Officer, South West Asia (Bahrain). He returned to the United States in 2001 and was on duty at the Naval District of Washington on 9/11. He has a lifelong interest in history and has written extensively on the Washington, Norfolk, and Pensacola Navy Yards, labor history and the history of African Americans. His previous books include African Americans in Slavery and Freedom on the Washington Navy Yard 1799 -1865, Morgan Hannah Press 2011. History of the Washington Navy Yard Civilian Workforce 1799-1962, 2004.

https://www.history.navy.mil/content/dam/nhhc/browse-by-topic/heritage/washington-navy-yard/pdfs/WNY_History.pdf

and the first complete transcription of the Diary of Michael Shiner Relating to the History of the Washington Navy Yard 1813-1869, 2007/2015 online:

https://www.history.navy.mil/research/library/online-reading-room/title-list-alphabetically/d/diary-of-michael-shiner.html

His most recent work includes Register of Patients at Naval Hospital Washington DC 1814 With The Names of American Wounded From The Battle of Bladensburg 2018,

https://www.history.navy.mil/research/library/online-reading-room/title-list-alphabetically/r/register-patients-naval-hospital-washington-dc-1814.html

The last three works were all published by the Naval History and Heritage Command. John served on active duty in the United States Navy, including Viet Nam service. He received his BA and MA in History from San Francisco State University. He can be reached at sharpjg@yahoo.com

Norfolk Navy Yard Table of Contents

Birth of the Gosport Yard & into the 19th Century

Battle of the Hampton Roads Ironclads