By John G. M. Sharp

At USGenWeb Archives

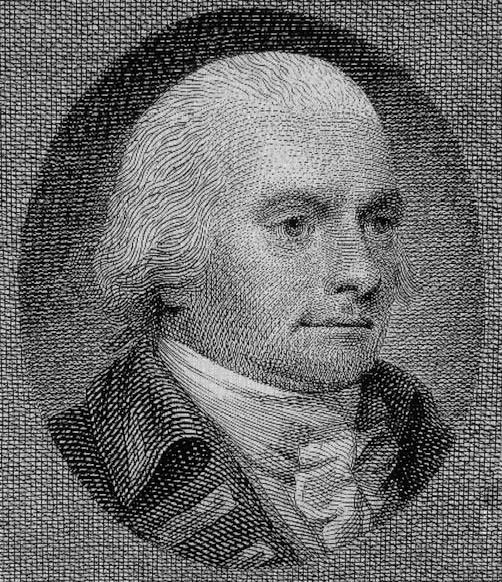

All rights reservedOn the evening of 21 September 1797, at 11 P.M., half dozen angry members of frigate HMS Hermione crew, their courage fueled on a stolen bucket of rum, rushed to Captain Hugh Pigot's cabin, smashed the door, and forced their way in.1

1. Pope, Dudley, The Black Ship (Henry Holt, New York, 1998), p. 156.

After overpowering the marine guards stationed outside, they hacked at Captain Pigot with cutlasses or tomahawks and one man with a musket and bayonet before throwing him overboard.3, 4 Two of the mutineers, American, Able Seaman John Farrel of New York (634) and Bosun's Mate Thomas Nash of Waterford, Ireland (179) took significant leadership roles during the mutiny.5 The mutineers then proceed to murder nine other officers.

2. Confession of Joseph Montell, March 1798, ADM 1/248, p.16.

3. Pope, p. 157.

4. Hannibal in Port Royal Harbour Jamaica on Thursday the 15 August 1799 for the Trial of Thomas Nash one of the Mutineers of His Majesty's late Ship Hermione (Court Martial James Irwin (Irvin), John Holford, Senior, John Holford, Jr. – PRO ADM 1/5344 May 23, 1798 British National Archives.

5. Convertitio, Coriann, 2011, The Health of British Seamen in the West Indies, 1770 -1806, PHD thesis University of Exeter https://ore.exeter.ac.uk/repository/bitstream/handle/10036/3918/ConvertitoC.pdf?sequence=3

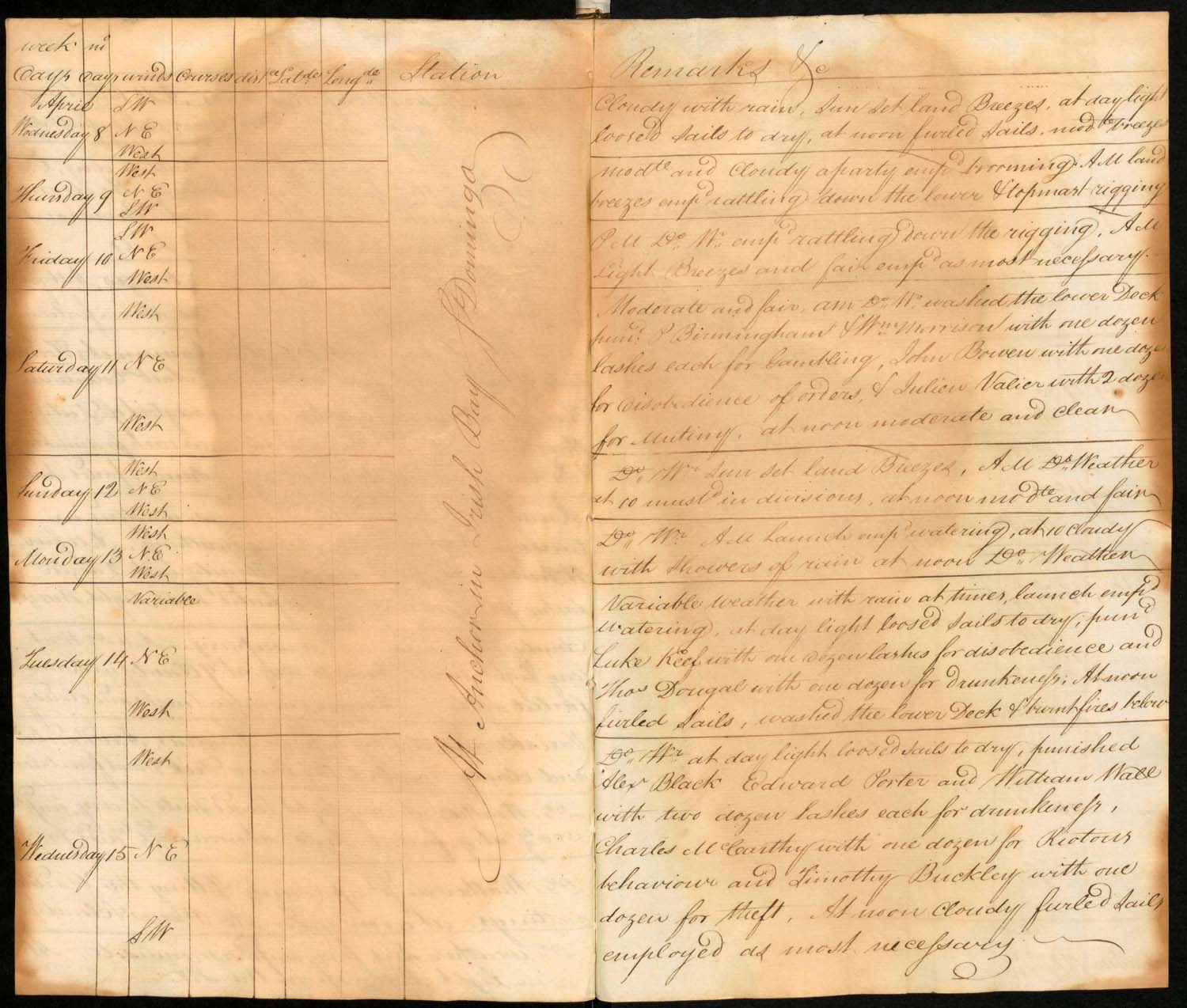

Dudley Pope has pointed out that captain Pigot, while in command of HMS Success, the frequency of flogging and its erratic nature showed a "complete lack of balance". Pope noted, for example, on 11 April 1795 Julian Valier, a seaman on HMS Success, was given twenty-four lashes for mutiny, one of the worst offenses in the Royal Navy apart from murder or treason, yet three sailors Alex Black, Edward Porter and William Wall on 15 April 1795, that same month, were given twenty four lashes for drunkenness, one of the most common infractions.6

6. Pope, pp.66, 343.

HMS Success deck log, 11 April 1795The HMS Hermione was recommissioned, as a fifth-rate frigate, under Captain John Hills, in December 1792. She sailed from Chatham Dockyard to Jamaica on 10 March 1793. The Hermione served in the West Indies during the early years of the French Revolutionary Wars. On 4 June 1794, under John Hills, the ship participated in the British attack on Port-au-Prince, where she led a small squadron that accompanied troop transports. Hermione had five men killed and six wounded in the attack. The British captured both the port and its defenses, and in doing so captured a large number of merchant vessels. Throughout her years in the Caribbean, the crew of the Hermione suffered repeated outbreaks of Yellow Fever and Malaria.

Death from disease, and not as a direct result of combat with the enemy, was in fact one of the navy’s biggest adversaries. Life on board a sailing ship was grueling and unhealthy. Ships teemed with refuse, rotting provisions, rats, insects, dirt and unclean drinking water. It is not surprising that these conditions resulted in diseases becoming widespread. Provisions for seamen to clean themselves and launder their belongings were not supplied by the navy, meaning the men usually slept in filthy hammocks and wore the same dirty clothing for months at a time.7

7. Convertitio, Coriann, 2011, The Health of British Seamen in the West Indies, 1770 -1806, PHD thesis University of Exeter https://ore.exeter.ac.uk/repository/bitstream/handle/10036/3918/ConvertitoC.pdf?sequence=3

The muster log of the HMS Hermione confirms the crew, as scholar Niklas Frykman has written, lived with the daily fear of – and in close proximity to death – through disease. Out of a shipboard population that usually hovered at just below 180, the death toll climbed to 134 men on the Hermione sailors died between December 1792 and July 1797, on average one man every ten days or so.8 During the course of 1794 most British forces were killed by Yellow Fever. Crew member David O’Brian Casey later wrote,

“In the Hermione alone,” we lost in three or four monthsw nearly half our crew, many from apparent good health, dying in a few days.9

8. Frykman, Niklas, The Bloody Flag, Mutiny in the Age of the Atlantic Revolution (University of California Press, Oakland, 2020), p. 168.

9 Ekirch, A. Rodger, American Sanctuary, Mutiny, Martyrdom and National Identity in an Age of Revolution (Vintage Books, New York, 2017), p. 9.

In the summer of 1794 the mortality rate for fever cases at the Port Royal Naval Hospital increased to 41%.10 Likewise later in the year, the registers of the Mole Naval Hospital, recorded the percentage of fatal cases caused by "fever" and the percentage of "fever" cases resulting in death rose to exceptional levels in the last quarter of the year, respectively seventy-three per cent and fifty-six per cent, excluding "intermittent" fevers.11 On 24 August 1794, Captain John Hills (1), the Hermione’s commanding officer, died from Yellow Fever at Port-au-Prince Hospital.12

10. Yellow Fever in the 1790’s The British Army in occupied Saint Dominque, David Greggus, Medical History, 1979,

23: 38-58, pp.40, n. 11 and 46. https://www.cambridge.org/core/services/aop-cambridge-core/content/view/89199FC7FE981F69B1C7D132CE170DBB/S0025727300051012a.pdf/

yellow_fever_in_the_1790s_the_british_army_in_occupied_saint_domingue.pdf11. Frykman, Niklas, The Bloody Flag, Mutiny in the Age of the Atlantic Revolution (University of California Press, Oakland, 2020), p. 168.

12. The Gentleman's Magazine (1850), Vol. 188, p. 662.

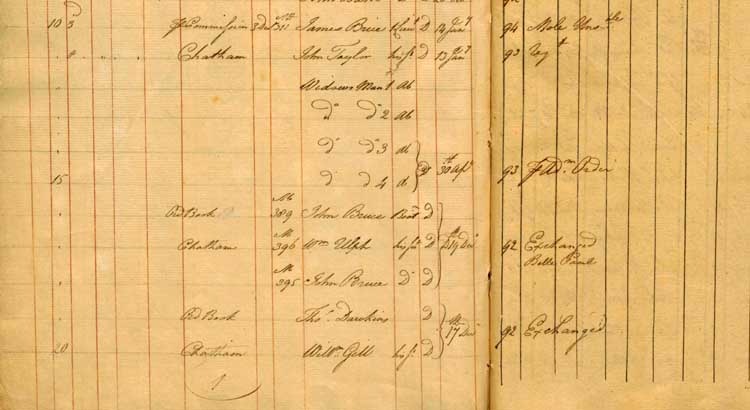

HMS Hermione, muster 7 April 1797 to 7 July 1797,

“Widows Men”, number 12 -15Widow's man was a fictitious seaman kept on the books of Royal Navy ships during the 18th and early 19th centuries so that their pay and rations could be redistributed to the families of dead crew members. This financial arrangement helped keep widows from being left destitute following the death of their seafaring husbands. The number of widows' men on a Royal Navy ship was proportional to the ship's size. A first-rate might have as many as eighteen, while a fifth-rate, like the Hermione, might have only three or four. The existence of widows' men served as an incentive for men to join the Royal Navy, rather than the Merchant Navy, as they knew that their wives would be provided for if they died.13

13. On the HMS Hermione muster (numbers 12 -15) and that of many other ships, were "widows’ men". A widow’s man was a fictitious seaman, entered on the muster whose wages would be set aside to be used to make payment to the families of dead crew members. See “The Purpose and Content of Musters” Captain Cook Society, https://www.captaincooksociety.com/cooks-life/cooks-ships/the-ships-cook-sailed-in/the-purpose-and-content-of-musters

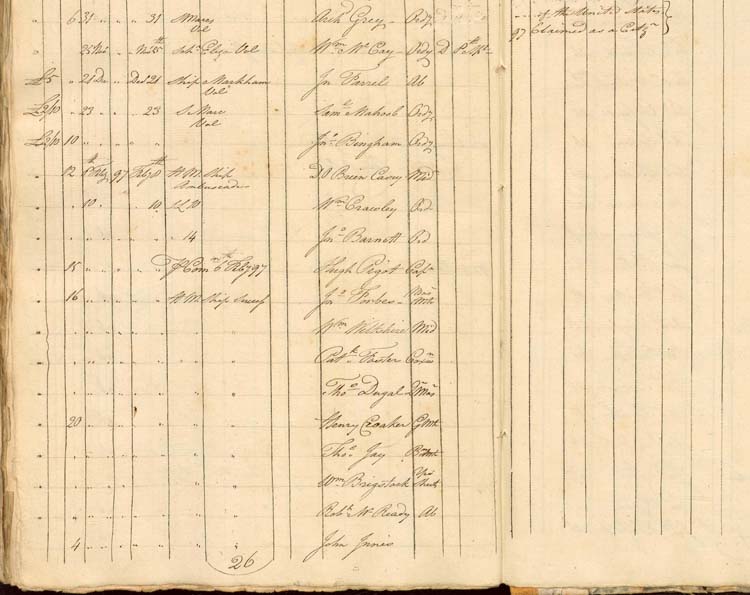

The last surviving muster book, July 1797, reflects the Hermione had a diverse crew, with about half of the crew born in England and a fifth in Ireland. The remaining sailors were from Germany, Norway, America, Canada, Denmark and Portugal. Two of the men David Black, no. 159 and William Lewis no. 252, were of African descent. At least twenty of these seamen were Americans, "among them mariners from Charleston, Norfolk, Philadelphia, New York and Nantucket.” Of the twenty Americans aboard the Hermione a slight majority appear to have received bonuses for "enlisting" with a distinct likelihood that the remainder had been pressed."

HMS Hermione muster 1797, p.26, Captain Hugh Pigot no.615

John Farrel, American, no. 634, was a leader of the mutinyAs he had when in command of the HMS Success, Captain Hugh Pigot (no. 615) on assuming command of the Hermione on 6 February 1797 continued to impress seamen. Many of these sailors’ were "pressed" or forcibly conscripted seamen from merchant vessels doing business in the Caribbean. For example, six Americans were impressed on 4 July 1797 from the American merchant ship Two Brothers. This impressment action and others like it led to a diplomatic incident and the intervention of the American Consul, Silas Talbot. The impressed men were eventually released.14

14. Frykman, Niklas, The Bloody Flag: Mutiny in the Age of Atlantic Revolution (University of California Press, Oakland, 2020), pp. 170, 248, n.13.

Regulations required the purser of each ship's company to list and from 1764 give the name of the sailor, age on boarding, place of birth, and whether pressed into service. They were also to notate ‘D' signifying Discharge which could include transfer to another ship, 'R' signifying Desertion (Run) and 'D.D.' Discharged Dead.

Warrant officers on board, HMS Hermione included the Sailing Master, William Turner (396), Purser Stephen Turner Pacey (no. 553) and the Surgeon (no. 594) Hugh T. Sansom. Each had a warrant from the Navy Board but not an actual commission from the Crown. Warrant officers had rights to mess and berth in the wardroom and were normally considered gentlemen; however, the Sailing Master was often a former sailor who had "come through the ranks", therefore might have been viewed as a social unequal. All commissioned and warrant officers wore a type of uniform, although official Navy regulations clarified an officer uniform in 1787, while it was not until 1807 that masters, along with pursers, received their own regulated uniform.15

15. Blake, Nicholas; Lawrence, Richard Books, The Illustrated Companion to Nelson's Navy, (Stackpole Books, Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania, 2005) p. 71.

The Purser: Stephen Turner Pacey was in charge of the purchase of supplies such as food and drink, clothing, bedding, hammocks and candles. Pacey would usually charge the supplier a 5% commission for making a purchase and charged a considerable markup when they resold the goods to the crew. While the purser was not in charge of pay, he had to track it closely since the crew had to pay for all their supplies, and it was the purser's job to deduct those expenses from their wages. The purser bought everything (except food and drink) on credit, acting as an unofficial private merchant. In addition to his official responsibilities, it was customary for the purser to act as an official private merchant for luxuries such as tobacco and to be the crew's banker. Pursers were notorious for giving short measure for victuals, clothing and on the money they made from the sale of tobacco. After a burial, the ship’s purser would record the dead man’s clothes and possessions. Typically these items were sold at auction to members of the crew with the proceeds going to deceased next of kin.

The Surgeon: Hugh Sansom’s duties included responsibility and oversight of the surgeon’s mate Lawrence Cronin (597), visiting patients at least twice a day, and keeping accurate records on each patient admitted to his care. As surgeon, Sansom would take morning sick call at the mainmast, assisted by his mates, as well as tending to injured sailors during the day. During sea battles, the surgeon worked in the cockpit, a space permanently partitioned off near a hatchway down which the wounded could be carried for treatment. The deck was strewn with sand prior to battle to prevent the surgeon from slipping in the blood that accumulated. In addition to caring for the sick and wounded, surgeons were responsible for regulating sanitary conditions on the ship.

Surgeon Sansom and his mates also oversaw the regular fumigation of the Hermione sick bay and sometimes whole decks by burning brimstone (sulfur), and maintained the ventilating machines that supplied fresh air to the lower decks to keep them dry.

Historians and medical researchers now recognize, that despite the best efforts, yellow fever and malaria were two of the unintended consequences of large scale sugar production in Jamaica and Haiti plantations. In these tropical locations, sugarcane was cultivated by a large enslaved population. The Caribbean had a plentiful supply of water for a continuous period of more than six to seven months each year, either from natural rainfall or through irrigation. These same conditions are also the perfect incubator for mosquitos. The mosquitos are vectors for both malaria and yellow fever. Both diseases were widespread in the tropical and subtropical areas that existed in a broad band around the equator and particularly in Cuba. The yellow fever virus is mainly transmitted through the bite of the mosquito, Aedes aegypti, but other mostly Aedes mosquitoes such as the tiger mosquito, Aedes albopictus, can also serve as a vector for this virus. In epidemiology, a disease vector is any agent which carries and transmits an infectious pathogen into another living organism. Yellow fever typically brings on high fever, muscle pain, headaches and nausea. In unfortunate cases, these symptoms are joined by jaundice, internal hemorrhaging with blood oozing through the nose and ears, delirium and vomit of partially coagulated blood with the color and constancy of coffee grinds, hence its Spanish name "vomito negro" or black vomit. This last stage is usually followed by multiple organ failure and death. Sailors often referred to yellow fever as "yellow jack" for the yellow pendant or flag ships and vessels flew as a warning to others of the presence of the disease.*As historian J. R. McNeil in his magisterial Mosquito Empire Ecology and War in the Greater Caribbean, 1620-1914, reminds us that it was not for nothing that yellow fever goes by the French Name "mal des matelots" (sailors disease) in the West Indies. Thus vessels like HMS Success and HMS Hermione unwittingly became super vectors with mosquito larvae hatching in the wet and damp spaces below deck.** Most of the Hermione crew down with yellow fever or malaria who departed the ship in Jamaica for Port Royal Naval Hospital or the Mole Naval Hospital, rarely returned. The 1797 Hermione muster below notated in all 127 men and boys as D.D. Departed Dead. The 1797 muster provides enumerates at least 90 men who died in hospital. Among the deaths on board,, falling overboard, accidental falls, bursting cannon and enemy action are listed as cause.* J.R. McNeil "Mosquito Empire: Ecology and War in the Greater Caribbean" (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 2010), 33-34 and Timothy C. Winegard "The Mosquito: A Human History of our Deadliest Predator" (Dutton: New York 2019), 26.

** McNeil, 51.Enlisted ratings most often found in this muster are: Landsmen abbreviated to ‘LM’, Ordinary Seaman abbreviated to ‘ord’ or ‘ordy’ and Able-Bodied Seaman abbreviated to ‘ab’ or ‘AM’ or ‘able’.

Duties of Enlisted Ratings:

Able Seaman, also Able-bodied seaman, was often abbreviated A.B. or ab. On British naval vessels an Able Seaman was typically considered the best seafarers with years of experience at sea and considered "well acquainted with his duty". The rating of A.B., is often found on ship's muster and payrolls: these two letters are frequently used as an epithet for the person so rated. He must be equal to all the duties required of a seaman in a ship--not only as regards the saying to "hand, reef, and steer," but also to strop a block, splice, knot, turn in rigging, raise a mouse on the main-stay, and be an example to the ordinary seamen and landsmen. Many former merchant sailors were rated as Ordinary Seaman, O.S., since they often lacked the requisite experience aboard a ship of war to rate A.B.

Ordinary Seaman abbreviated “O.S." ord, or ordy. Ordinary Seaman in the British Navy ranked above Landsman and below Able Seaman. An Ordinary Seaman who gained sufficient experience at sea and "knew the ropes", that is, knew the name and use of every line in the ship’s rigging, could be promoted to A.B. An Ordinary Seaman’s duties aboard the HMS Hermione included “handling and splicing lines, and working aloft on the lower mast stages and yards.

Landsman abbreviated "LM." Landsman was the rating given to new recruits, novices with little or no experience at sea. Landsmen performed menial, unskilled work aboard ship. A Landsman who gained sufficient experience could be promoted to Ordinary Seaman.