Norfolk (Gosport) Naval Hospital

Female Employees 1810 to 1842

Addendum: Edward Fitzgerald Sr., (1785-1857) Purser USN

By John G. M. Sharp

At

USGenWeb Archives

Copyright All rights

reserved

This paper examines the largely forgotten but crucial part African American labor played at the Gosport (Norfolk) Naval Hospital, especially the role of black women which became paramount in the provision of patient care and sustenance. These enslaved women both lived and worked at the hospital as care providers. There they served during the War of 1812, the awful yellow fever epidemics of 1821 and 1855 and the great cholera epidemic of 1832. At great risk to themselves, they helped nurse and feed the sick and dying. While many historians have written about medical care, the participation and contributions of black women as nurses and hospital workers at Gosport in the antebellum era have often been overlooked.

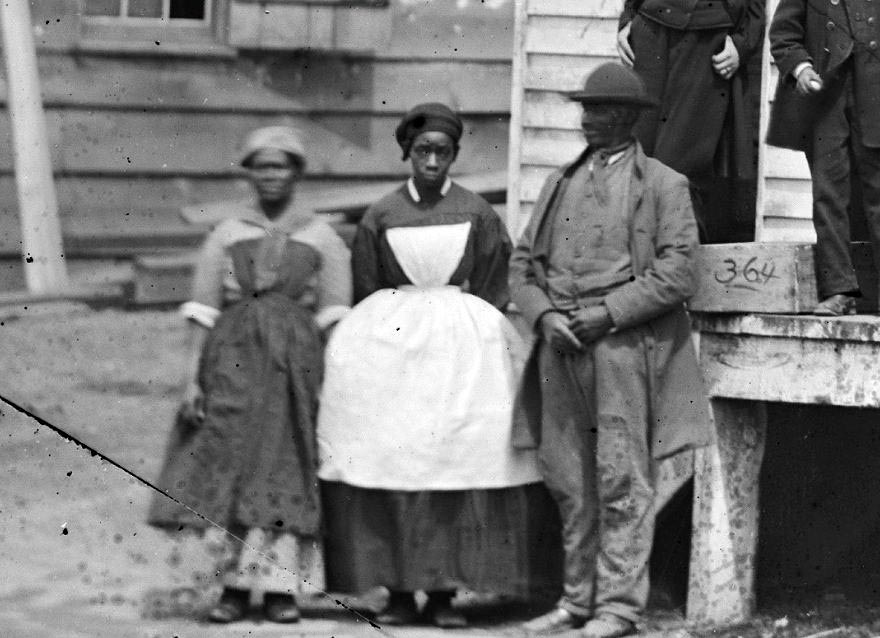

Hospital workers, (Library of Congress Washington DC)All of the basic information concerning black employment is etched in the surviving documentary record, but historical attention has been focused on naval medical practice, administration and leadership. Dr. Richmond C. Holcomb’s pioneering A Century with the Norfolk Naval Hospital 1830-1930 briefly mentions early servants, nurses, cooks and washers, yet provides no indication these positions were filled by blacks or enslaved labor. Similarly Harold D. Langley’s 1995 informative A History of Medicine in the Early U.S. Navy traces the evolution of naval medicine from 1794 to the establishment of the Bureau of Medicine and Surgery in 1842. Langley’s account of naval medicine includes useful biographical sketches of important surgeons and practitioners and the background of the creation of naval hospitals. Langley like Holcomb though was hampered by the limited number of surviving records and a shortage of pertinent data. While this history provides a useful summary of the creation of the naval hospitals at Norfolk, Pensacola and Washington DC here too there are no entries for African Americans or enslaved labor.1

1 Richard C. Holcomb A Century with Norfolk Naval Hospital (Printcraft Publishing: Norfolk 1930), 170-171

Harold D. Langley’s 1995 A History of Medicine in the Early U.S. Navy (Johns Hopkins Press: Baltimore 1995), 13, 320-321

Firsthand testimony was given by George Teamoh, a former slave who toiled at Gosport Navy Yard from the 1820s to the 1840s wrote from his own direct experience of the shipyard’s involvement and of its large slave workforce. He wrote "slavery was so interwoven at that time in the very ligaments of government that to assail it from any quarter was not only a herculean task, but one requiring great consideration, caution and comprehensiveness."2 Consequently, as one distinguished historian of slavery has cautioned, when looking for enslaved labor the "hiring practices were not based upon open contractual negotiations but unwritten gentleman's agreements which have only been discovered by searching for those little incidents or small moments where explanation in writing was demanded."3 Searching for enslaved and free blacks in federal, military and civilian personnel data can be daunting.4 However, using recently digitalized hospital registers for the years 1818-1823 and 1830-1861 in conjunction with patient case papers 1825-1827 and officer’s letters from these years, a clearer picture emerges of how the naval hospital utilized enslaved labor.

2 George Teamoh God Made Man Man Made the Slave The Autobiography of George Teamoh editors F.N. Boney, Richard L. Hume and Rafia Zafar Mercer University Press: Macon 1990, 84

3 Ernest E Dibble Antebellum Pensacola and the Military Presence (Pensacola News Journal: Pensacola 1974), 62

4 John G. Sharp Documents Reflecting African Americans in Slavery and Freedom in the District of Columbia 2010. Accessed 20 August 2018 http://genealogytrails.com/washdc/slavery/slaveryintro.html

Through the first half of the nineteenth century, both Gosport Navy Yard and Naval Hospital extensively utilized enslaved labor.5 Slaves were employed for economic reasons and as engineer Loammi Baldwin wrote on 17 April 1830 to Commodore James Barron "we can dismiss them (slaves) whenever we are dissatisfied with them. . ."

Some idea of slavery's human scale and sheer numbers involved can be found in this excerpt from a 12 October 1831 letter of Commodore Lewis Warrington to the Board of Navy Commissioners in response to various petitions by white workers.

5 Portsmouth Naval Shipyard Museum https://www.theclio.com/web/entry?id=11938 accessed 12 August 2019

Christopher L. Tomlins (1992) In Nat Turner's Shadow: Reflections on the Norfolk Dry Dock Affair of 1830-1831, Labor History, 33:4, 494-518.

http://www.usgwarchives.net/va/portsmouth/shipyard/nnytomlins.pdfThere are about two hundred and forty-six blacks employed in the Yard and Dock altogether of whom one hundred and thirty-six are in the former and one hundred ten in the latter – We shall in the Course of this day or tomorrow discharge twenty which will leave but one hundred and twenty-six on our roll – The evil of employing blacks, if it be one, is in a fair and rapid course of diminution, as our whole number, after the timber now in the water is stowed, will not exceed sixty; and those employed at the Dock will be discharged from time to time, as their services can be dispensed with – when it is finished, there will be no, occasion for the employment of any.6

6 Louis Warrington to Board of Navy Commissioners 12 October 1831 NARA RG45 transcribed John G. Sharp, accessed 12 August 2019 http://www.usgwarchives.net/va/portsmouth/shipyard/nnysharp.html#enslaved

Like the shipyard, the hospital readily employed slaves. Conversely there are no clear records of free blacks prior to the Civil War years employed at the Gosport Naval Hospital. Most naval officers and white civilians were distrustful of free blacks and many shared the view of Commodore Lewis Warrington who wrote that free blacks were "a great inconvenience if not an evil…"7 White workers at the Norfolk shipyard were especially alarmed by any attempt to place blacks in the skilled trades: "There should be no slave carpenters – nor bricklayers - nor stonemason - nor ditcher nor any slave bred for any mechanical art." For Warrington and numerous others, the 1831 Nat Turner rebellion had shaped their views; they did not want "free blacks" aboard ship, in their communities, hospitals or working in the shipyards. Shortly after the Nat Turner rebellion, a move to rid Virginia of free blacks gathered momentum with one hundred eighty-two white Norfolk residents writing "that despite their efforts to rid the state of free blacks, their numbers are rapidly increasing." The petitioners proposed that "Providence has provided a remedy in the Society for colonizing them in Africa" and requested the legislature provide annual appropriations to aid in transporting "that indigent, ignorant and wretched people to the land of their ancestors."8 This proposal never really caught on for most blacks Virginia was home and had been for centuries. For the white slaveholders slavery was profitable and the petitioner's scheme was viewed as expensive. At the Norfolk Navy Yard, the area’s largest employer, white mechanics increasingly pressured employers to exclude free black labor. Instead slaveholders simply chose to place greater restrictions on the residency and movement of free blacks. Secondly white officers and civilians sought more slaves to lease to the burgeoning federal installations and those working at the shipyard or hospital used their positions to hire more bondsmen or to further the interest of slaveholding family or friends. The naval hospital at Gosport was not exceptional, for the hire of enslaved labor existed with the tacit and sometime explicit support of the Department of the Navy at both Washington Navy Yard and at Pensacola Navy Yard.

7 Warrington to Paulding 9 September 1839 NARA M125 "Captains Letters" 1 Sept 1839 to 30 Sept 1839, letter number 38

Gary Collison Shadrack Minkins from Fugitive Slave to Citizen (Harvard University Press: Cambridge 1997), 19 and 38

8 Library of Virginia Citizens of Norfolk dated 22 January 1833 to the General Assembly of the Commonwealth of Virginia petition number 11683301 Race and Slavery Project https://library.uncg.edu/slavery/petitions/details.aspx?pid=2659

An economic explanation for enslaved at Gosport Navy Yard and the hospital was offered in a 10 May 1808 letter from Commodore John Cassin at Washington Navy Yard. Cassin later served for a decade as commandant of the Norfolk Navy Yard 1812 -1821 a period which saw the expansion of slave labor. In this letter Cassin pleaded with the Secretary of the Navy Robert Smith to continue leasing slaves. "Understanding it is the intention of the Secretary of the Navy to discharge all Slaves employed in this Yard ,I Beg leave to observe there are but very few white men in this neighborhood that can be found to fill their places even for one fourth higher wages."

Commodore Thomas Tingey, (Cassin’s superior) fully endorsed enslaved labor and when the Secretary of the Navy Smith questioned the practice replied (19 May 1808) citing the custom of the service and implored Smith to reconsider any proposed ban:

It is well known to be established custom, that whenever an officer has been ordered on duty - so, as to give him the command of men, entered on the muster roll for pay &c said officer hath invariably entered thereon one or two at least of his own servants or taken such servants from the men so entered - It would appear then Sir - singular and tend to excite unpleasant feelings, were myself and the Officers under my command at this place, to be the only exceptions to the customary indulgence - An indulgence also common to every officer, in the Military and Marine service- and generally in number according to Rank. It is therefore hoped with submission, by myself and Officers attached to this yard, that you would please to take this matter into consideration - and sanction to us the indulgence common to all our brother officers here to be allowed service and the quantum to each.

In a draft reply (no date) Smith wrote "certainly not to allow them emoluments for their servants slaves to them & not in any way engaged for the public" Despite this enslaved labor continued.

The Board of Navy Commissioners concerned about such abuses on occasion, took more drastic steps to limit to the number blacks at Norfolk and the other shipyards and installations. On 17 March 1817 they issued a circular to Commodore Cassin and other shipyard commandants, banning employment of all blacks and apparently questioning the activities officers and senior civilainsAbuses having existed in some of the Navy yards by the introduction of improper Characters for improper purposes, The Board of Navy Commissioners have deemed it necessary to direct that no Slaves or Negroes, except under extraordinary Circumstances, shall be employed in any navy yard in the United States, & in no case without the authority from the Board of Navy Commissioners.

This circular had little effect, characteristically such orders restricting black employment were followed quickly by a period of waivers and exceptions as officers, senior civilian employees and slaveholders lobbied and pressed the Secretary and the Board of Naval Commissioners to make accommodation for slave labor. In April 1818 as commandant at Norfolk an undeterred Commodore Cassin wrote the Secretary of the Navy for yet more slaved labor "finding it absolutely impossible to do labor required in this yard without taking in some black men in consequence of the white men sporting with their time; in the manner that they do; and leaving the yard frequently … I have yesterday taken in twenty four blacks…"

Sources:

Cassin to Robert Smith NARA M125 NARA RG 45

Tingey to Robert Smith NARA RG 260 M125 "Captains Letters", letter dated 19 June 1808, volume 11, number 75

Cassin to Benjamin Crowinshield NARARG260 M125 "Captains Letters" letter dated 27April1818, volume 58, letter number 36

BNC Circular to John Cassin and other Commandants of Naval Shipyards, 17 March 1817, RG 45, NARA.In Virginia where the vast majorities of African Americans were enslaved, hiring free blacks was viewed with suspicion and considered a threat to the stability of the system.9 Leasing enslaved workers was another matter, for despite occasional protests by white workers at Gosport in 1831 and 1839 and the concerns raised by the Secretary of the Navy in 1846, the practice was profitable and continued until the Civil War.10 Slaveholders as early as 1813 benefited from a Department of the Navy directive that treatment and medical care be extended to "…Master or laboring Mechanic or common laborer employed in the navy yard that shall receive any sudden wound or injury, while so employed in the Yard; he shall be entitled to temporary relief." The Secretary also ordered similar medical attention for enslaved workers in the navy yard.11 This medical policy for enslaved workers was confirmed on 2 June 1838 by Secretary of the Navy Mahlon Dickerson.12

9 Todd L. Savitt Medicine and Slavery The Disease and Health Care of Blacks in Antebellum Virginia (University of Illinois Chicago 1978) 207-208

10 Lewis Warrington to the Secretary of the Navy 12 October 1831 http://www.usgwarchives.net/va/portsmouth/shipyard/nnysharp.html

John G. Sharp A Norfolk Navy Yard Slaveholders Petition to the Secretary of the Navy, June 21, 1839http://www.usgwarchives.net/va/portsmouth/shipyard/nnysharp6.html

Gary Collison Shadrack Minkins from Fugitive Slave to Citizen (Harvard University Press: Cambridge 1997), 25

John G. Sharp List of Gosport Navy Yard Employees Military and Civilian, 1846 http://www.usgwarchives.net/va/portsmouth/shipyard/nnysharp13.html

Robert S. Starobin, Industrial Slavery in the Old South (Oxford University press: New York third edition 1972), 32

11 William S. Dudley, editor The Naval War of 1812: A Documentary History Volume II (Naval Historical Center: Washington, DC, 1992), 124. For examples see John G. Sharp Register of Patients at Naval Hospital Washington DC 1814 With The Names of American Wounded From The Battle of Bladensburg Naval History and Heritage Command 2018 https://www.history.navy.mil/research/library/online-reading-room/title-list-alphabetically/r/register-patients-naval-hospital-washington-dc-1814.html#ft12

12 Mahlon Dickerson to W.G Bolton 2 July 1838 1838 http://www.usgwarchives.net/va/portsmouth/shipyard/pensacola-sharp-2.html

Military policies regarding enslaved labor were haphazard, more a mix of differing plans and ideas than a coherent program. Typically these policies followed those first utilized in 1792 by the District of Columbia Board of Commissioners for the construction of the U.S. Capitol and the White House. In most all cases the federal government did not purchase slaves but instead leased or rented enslaved labor from private individuals in local communities, surrounding forts and naval shipyards. For employers the increased presence of enslaved blacks in the work force had a secondary benefit, for it proved a very useful check on white workers wage demands and kept "affairs cool." The "cooling" effects of slave labor on free wages meant that laborers at the mostly all white Massachusetts Charlestown yard received wages of $ 1.00 a day and sometimes more, while the men in Washington, DC., white and black, earned $0.72.13 To avoid public scrutiny most of these agreements to provide enslaved labor between military officials and slaveholders were verbal, so called "gentleman’s agreements."14

13 Thomas Johnson, David Stuart, and Daniel Carroll, Commissioners to Thomas Jefferson, 5 January 1793 Commissioners Letter book Vol. I, 1791--1793, NARA RG and for wage difference between Charlestown and WNY see Linda M. Maloney, The Captain from Connecticut: The Life and Naval Times of Isaac Hull (Boston: Northeastern University Press, 1986), 421.

14 Thomas Hulse, "Military Slave Rentals, the Construction of Army Fortifications, and the Navy Yard in Pensacola, Florida, 1824-1863," (Florida Historical Quarterly, 88, Spring 2010), 497-539.

During the first half of the nineteenth century hospitals were few, especially in the South, with the exception of those run by Catholic religious orders, hospitals relied on male nurses or slaves to tend to patients. The naval service had long used male nurses on shipboard and shore stations. Nursing remained until the Civil War for the most part an exclusively male occupation, except at the naval hospitals in Gosport and Pensacola which quickly adapted to hiring enslaved females as cooks, washers and nurses. Local slaveholders, many of whom were naval officers such Commodore James Barron, Commodore Lewis Warrington, Surgeon Dr. Thomas Williamson, Dr. Isaac Hulse, Naval Purser Edward Fitzgerald and white civilian master mechanics, were all able to place their own bondsmen in positions at the naval shipyard and naval hospital.15 Such hires were rarely formalized; agreements committed to writing are rare and, with the exception of the wages due the slaveholder, are often short and vague although some specified a period of time. In 1809 the United States Congress passed a law requiring bidding for contractual services and that the Government publicly announced what it wished to buy and everyone was given an opportunity to bid on the work. Verbal contracts or "gentleman's agreements" were one means of getting around this barrier.16

15 Commodore James Barron came from a prominent Norfolk slaveholding family. The hospital case files make multiple references to "Commodore Barron’s servant" e.g. 14 July 1825 and 25 January 1826. The 1830 census reflects Barron had three slaves with him at the navy yard. The 1830 census also shows Dr. Thomas Williamson had eight slaves at Norfolk and on 9 September1830 Williamsons even wrote the Secretary of the Navy to request to take with him to sea in the USS Brandywine "a servant who is a slave…" Earlier that year Commodore Lewis Warrington too (25 January 1825) had requested the Secretary of the Navy’s permission to add a yet a second enslaved man to serve him aboard since "they were in the habit of attending on me always…"

For Dr. Isaac Hulse and slaveholding, see John G. Sharp Early Pensacola Navy Yard in Letters and Documents to the Secretary of the Navy and Board of Navy Commissioners 1826-1840 accessed 17 August 17, 2019

http://www.usgwarchives.net/va/portsmouth/shipyard/pensacola-sharp.html16 Thomas Hulse, "Military Slave Rentals, the Construction of Army Fortifications, and the Navy Yard in Pensacola, Florida, 1824–1863," (Florida Historical Quarterly, 88, Spring 2010), 516

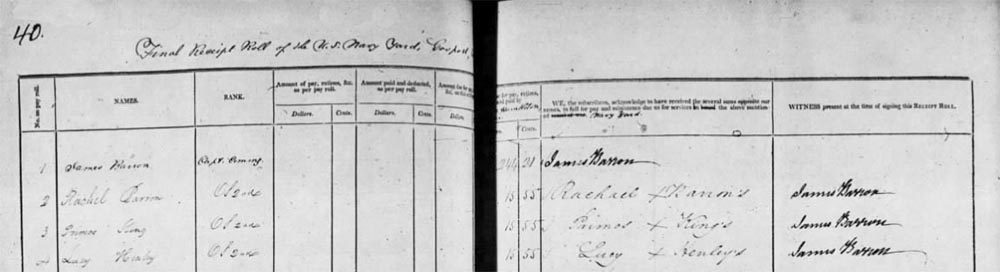

Slave hire agreements were both the chief means to obscure slave rentals and avoid public scrutiny. Those committed to writing are rare with the exception of the wages due the slaveholder are often short and vague although some specified a period of time. Numerous African Americans were not enumerated as enslaved for they worked in the shipyard "Ordinary" where they were deceptively enumerated as "Landsman" or "Ordinary" Seaman. As late as 6 December 1845, commandant of the Gosport Navy Yard Commodore Jesse Wilkerson belatedly confirmed the deceptive practice to the Secretary of the Navy and wrote that "a large portion of the ordinary" had been slaves for many years.17 In some instances this pretense was blatant, as on the 1830 Gosport Navy Yard muster where two enslaved women "Rachel Barron" and "Lucy Henley" are enumerated as Ordinary Seaman 2nd class, with Commodore James Barron signing for their wages.18 References to slaves in the hospital case files and letters are frequent and often signaled by the exclusive use of the familiar or occupational names such as "Capt. Warrington’s (Serv.) Henry," "Commodore Barron’s servant "Fanny the washerwoman", "washerwoman Isabella", "the washerwoman" or just the "washerwoman’s child"

17 John G. Sharp List of Gosport Navy Yard Employees Military and Civilian, 1846 accessed 21 August 2019 see Wilkinson to Bancroft 6 December 1845 NARA M125 "Captains Letters" Letter Received from Captains 1805 -1885, 1 Nov 1845 – 31 Dec 1845, dated 6 Dec 1845, letter number 84, 1-2

18 "Final Receipt Roll of the U.S. Navy Yard, Gosport " Miscellaneous Records of the Secretary of the Navy NARA RG45 Muster Rolls dated 1830, page 40 Rachel Barron is enumerated as number 2 O.S.2nd wage $ 15.55 and Lucy Henley number 4, O.S.2nd wage $15.55 both with wages signed by James Barron, roll number 0183

Image of the "Final Receipt Roll of the Gosport Navy Yard" page 10, first quarter 1830, line no. 2 Rachel Barron O.S. 2nd

and no. 4 Lucy Henley O.S.2nd. Both women’s wages signed for by Commodore James BarronVirginia slaveholders regularly leased their slaves for a year.19 One slave dealer advertising "Negro Hiring" told his customers to inform him "as early as practical" while another noted this should be done "soon after Christmas". In 1839 a group of white Norfolk shipyard employees explained the process of leasing of slaves to Commodore Lewis Warrington.

19 John G. Sharp A Norfolk Navy Yard Slaveholders Petition to the Secretary of the Navy, June 21, 1839 accessed 17 August 2019 http://www.usgwarchives.net/va/portsmouth/shipyard/nnysharp6.html

Richmond Inquirer 1 January 1847, 4

Having hired these labourers for the year, they are [now] bound by the usual obligation to pay for them – If they are discharged, the only resort would be to hire them to persons out of the Yard & not in the employ of the government, at a great loss; had the individuals thus hiring them, will in all probability, reenter them & enjoy a profit for their services, increased by the loss which the undersigned must necessarily sustain – It is proper here to add that a number of the labourers of this description in the Yard, are owned by the Mechanics here who entered them, and the difficulty of hiring them out, if discharged, at this advanced period of the year is obvious. 20

20 Warrington to the Secretary of the Navy NARA M125 "Captains Letters" 1 June 1839 to 30 June 1839, letter dated 21 June 1839, number 77

John G. Sharp A Norfolk Navy Yard Slaveholders Petition to the Secretary of the Navy, June 21, 1839http://www.usgwarchives.net/va/portsmouth/shipyard/nnysharp6.html

In the Norfolk area and throughout the South, slaves were normally leased for the year beginning in January. At the hospital, for instance, the terms for enslaved women Delilah Bradford and Isabella Cooper, AKA Arabella Cooper, are recorded: "Delilah Bradford Entered as Hospital Cook at $ 5 per month one year commenced January 1, 1822" and "Isabella Cooper Entered as Hosp. Washerwoman at $ 5 per month for one year from the 11th of January 1825."

While the shipyard and naval hospital hired the slaves of officer’s and civilian workers, they also could rely on the Navy Agent. Navy Agent’s negotiated contracts for the Department of the Navy. The position of Navy Agent was a political appointment and a lucrative post for agents received up to 2% on all public contracts. Agents contracted for a wide variety of materials, foodstuffs and services including enslaved labor in Virginia, Florida and District of Columbia with local slaveholders.

The Norfolk Navy Agent Miles King (1786 -1849) was a wealthy and prominent resident, a Mayor of Norfolk (1832-1839) and a dealer in slaves. King held the position of Navy Agent from 1816-1830. The 1830 U.S. Census for Norfolk Virginia reflects King possessed 26 slaves. He regularly ran notices in the Norfolk Gazette and Norfolk Beacon to sell or rent slaves for private individuals, e.g., 22 June 1812 9, Oct 1820 for a sale of "Fifteen Likely Negroes" and the following month (23 November 1820) acted in his capacity as agent for the shipyard and naval hospital for a sale of condemned government property.

Some Navy Agents like Samuel Overton at Pensacola Navy Yard publicly recruited enslaved labor through newspaper advertisements, Pensacola Gazette, 13 July 1827. Florida was remote area with a limited supply of labor, thus even the commanding officer, Commodore W.C. Bolton, felt the need to notify local slaveholders in the Floridian and Advocate, 10 September 1836, that the shipyard was offering good wages and medical care for slaves. Norfolk’s proximity to a large and ready supply of enslaved labor probably meant there was little need to advertise. In 1830 Miles King was charged with malfeasance and padding construction contracts at the Norfolk Navy Yard and removed from his post. In Congressional testimony, King’s accounting practices as Naval Agent at Norfolk, VA, were said to have created a "$40, 000 a year self-payment."Sources:

The Papers of Andrew Jackson Volume VII, 1829 editors Daniel Feller, Harold D. Moser, Laura-Eve Moss & Thomas Coens (University of Tennessee Press: Knoxville 2007),348, 392-394

John G. Sharp Early Pensacola Navy Yard in Letters and Documents to the Secretary of the Navy and Board of Navy Commissioners 1826-1840 http://www.usgwarchives.net/va/portsmouth/shipyard/pensacola-sharp-2.html accessed 30 August 30, 2019

The Virginia Historical Society, Manuscripts Division https://www.virginiahistory.org/sites/default/files/uploads/AAG.pdfSmith, Francis Williamson (18381865), papers, 18101947. a bond, 1810 (section 1) 21 Since most slaves were illiterate, few left journals, letters, diaries, etc., so documentation on their daily lives is poor. Most of the surviving documentation that does exist on enslaved hospital workers comes from Department of the Navy records and medical officers’ letters.

21 Terms of service for Delilah Bradford beginning 1 January 1822 were written on an unnumbered front end page, Records of the Bureau of Medicine and Surgery Field Reports Case Files for Patients at Naval Hospitals Register of Patients Naval Hospital Gosport, Volume 5, 1818 - 1823 NARA RG 54.

By 1826 Surgeon Thomas Williamson headed the hospital; he would have the greatest influence of any individual upon the first quarter century of its existence. Dr. Williamson’s twenty-six regulations reflected his attitudes towards staff servicemen and medical hygiene. Three of them No.1, No. 4 and No. 16 deal with the hospital staff they are:22

22 James Alsop, Research Note: The Code of Regulations for the First U.S. Naval Hospital, Norfolk, Virginia, 1838 Northern Mariner /Le marin de nord 59-67

https://www.cnrs-scrn.org/northern_mariner/vol21/tnm_21_60-67.pdf accessed 21 February 2019.No. 1 The officers and others at the Hospital should be as follows: one Surgeon, one Passed Assistant, and one young assistant, one Steward, two Cooks, two washers, four Nurses, four boatmen, two boys, for dispensary, and one porter, to be increased, or diminished, according to the number of sick, at the discretion of the Surgeon, approved by the Commanding Officer. All others attached to the Hospital are to be considered as belonging to the service and subject to the same rules and regulations that all are governed by.

No. 4 No officer, or other inmate at the Hospital, or officers of the Navy, are to punish in any manner, persons who are in the charge of the Medical officers, but are to report to them, when those who are under their charge, are guilty of any offense.

No. 16 Every part of the Hospital is to be visited daily by a Medical officer, whose special duty it will be, to see that every part is kept clean – Wards dry, and well aired –Beds, and bedding, clean, and frequently aired - patients clean and well clothed. The provisions for the sick are to be well cooked and under the direction of the [hospital] steward to be properly distributed. And also, he should not allow under any consideration, the clothes of the Patients, in, and near, their beds. Their clothes aired frequently, and to be kept clean.At the hospital Dr. Williamson’s strict stress on cleanliness meant hard work for all but especially for washers Fanny Ballott and Isabella Cooper. The two women were charged with cleaning all the laundry, on average thirty-six beds per week at two sheets and one pillow case per bed. Laundry included bedding, covers, patient clothes and bandages. The women first sorted then washed them in boiling water, rinsed and dried. The work was backbreaking, the hours long. The hospital washers were expected to make soap. "Once the sheets and clothes were rung out, they were put in boiling water to kill any lice that still remained. After they were boiled, the clothes were taken out with a laundry stick and rinsed three times. The first rinse was in hot water, then cool water, then cold water. After which came the bluing process. A laundress dyed some water light blue, then swished the clothes in it. This was to make the clothes white again, since the soap turned them yellow.23

23 "Laundry" Civil War Trails at Homestead Diorama Museum, 24 November 2018, Aresin, accessing 22 August 2019 https://civilwartails.com/

At Gosport the hospital nurses, washers, cooks, and laborers worked what was called dark to dark, in essence a twelve-hour day. The schedule was later changed to a ten hour day in 1840. At the hospital washers were in frequent contact with dirty cloths, sheets and bandages, many soiled with blood and/or fecal matter. In addition they routinely risked burns, slips and falls in the wash house and the danger of burns in boiling water. The hospital records also make clear that the washers were expected to assist the nurses and cooks (see Delilah Bradford). Blacks had long performed as nurses on plantations and with the urban communities of Virginia. To black women by necessity often fell the prenatal and obstetrical care of whites and blacks, especially in rural areas the black midwives were a common feature at the birth of children, with many masters preferring to employ them rather than incur the fees of white doctors.24

24 Savitt 182

In 1830 the new Gosport Naval (Norfolk) Hospital was completed and ready to go into commission. The new hospital facility was staffed by Naval Surgeon Thomas Williamson, Assistant Surgeon James Cornick; they were complemented by a support staff of one white steward, five African Americans, two nurses, two washers, and one cook.25 The new staff was augmented by four more enslaved workers: a messenger, an assistant cook and two laborers. Prior to the creation of the naval hospital at its present Portsmouth location, rudimentary medical facilities were available on the Gosport (Norfolk) Navy Yard.26 The old hospital building was positioned on the navy yard, known as "the Marine Hospital" and it was two stories high and stood in the center of the shipyard.

25 Holcomb 168 - 170

26 The U.S. Naval Hospital Ticket and Case Papers, for Gosport Naval Hospital 1825 -1827 NARA RG -52 Volume 5, entries for 1825 has multiple entries for Fanny and confirm her enslaved status . Norfolk Station Muster 1825, p.206 Fanny Ballot "Washer" enumerated no. 50 Miscellaneous Records of The Navy Department 1825,Roll: 0157

"Captains Letter s" Cassin to Crowninshield 8 September 1817 NARA M125 RG260 Volume 55, letter number 8

NARA RG 52: Records of the Bureau of Medicine and Surgery, 1812–1975. Case Files for Patients at Naval Hospitals and Registers Thereto: Registers of Patients 1812–1929.Volume 5

This ramshackle wooden structure had formerly housed the boatswains and gunners storerooms. On 8 September 1817 Gosport commandant Commodore John Cassin wrote to Secretary of the Navy Benjamin Crowninshield to express concern at "having the Hospital placed in the Center of the yard having lost five men in the first instant one sergeant & three private marines and one seaman , which was seen by all at work & have created such alarm that the above one half the laborers have left the yard apprehensive of some contagious disease prevailing …" Cassin knew this structure well for he had been a patient there multiple times in the years he served as commandant. Cassin suffered hepatitis, a disease that probably killed him in1822. His letter reflects how uneasy and frightened his marines, seamen and civilian workforce were by their closeness to infection and death. While his letter does not mention the type of disease, he is particularly concerned that proximity to the hospital not only spreads infection but destroys morale as well. Like many slaveholders Cassin has naught to say and may never have noticed the many enslaved "servants" such as Delilah Bradford, Fanny Cook or Lydia Smith who scrubbed, cleaned and cooked for his comfort.

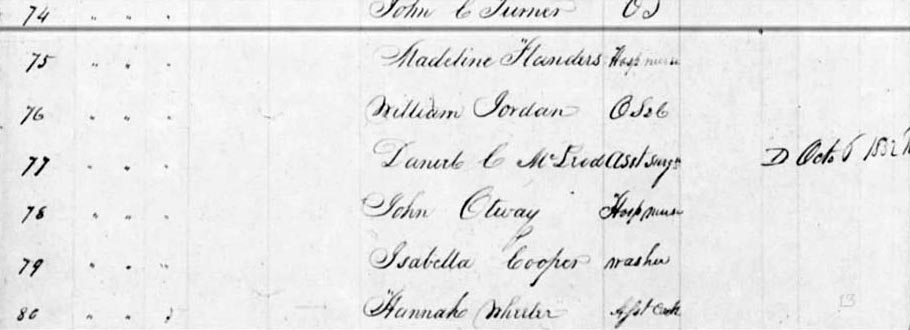

Cassin’s letter apparently did not merit a response and no action was taken and by the 1820’s the building hospital still shared space with a gunner’s store, pursers store and smelled of tar, horse droppings and human waste. The support staff of enslaved blacks did almost all the necessary work as nurses, cooks, washers and gravediggers. By the 1830’s the hospital was staffed with five and sometimes six enslaved female workers. The 1832 Gosport Naval Hospital muster records the first female nurse no.75 Madeline Flanders.27

27 Muster roll Gosport Naval Yard and Hospital 1Oct 1832 to 31 Oct 1832, p.146, line 75 Madeline Flanders nurse, Miscellaneous Records of the Secretary of the Navy, roll 183, NARA GR 45.

1832 muster for Gosport Naval Hospital with the first female nurse, Madeline Flanders number 75

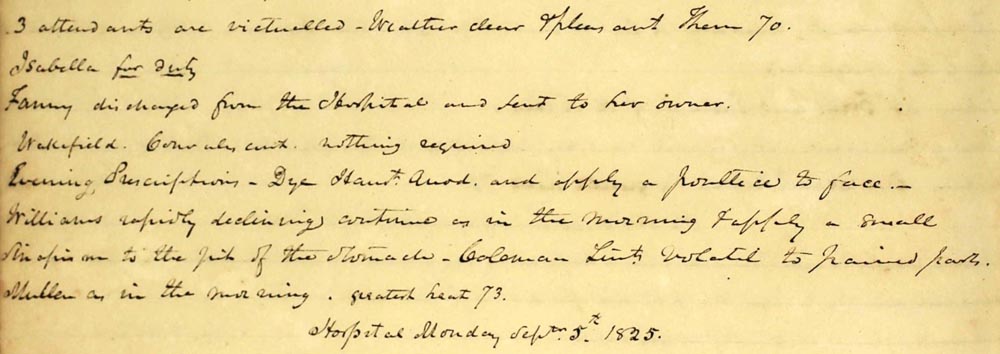

along with Isabella Cooper washer and Hannah Wheeler assistant cookWe know little about these first hospital workers and as Frederick Douglas once famously remarked "Genealogical trees do not flourish among slaves."28 Entries in the case files for 1825 confirm these women were enslaved; on 17 August 1825 there is a note regarding "Washerwoman’s child R of rice with Calomel". Calomel was a white tasteless power which consisted of mercury chloride and was used in the nineteenth century for treatment of malaria, as a purgative and for teething babies. Later notes indicate that the woman may have been Isabella Cooper for on 26 August 1825 we read, "The woman & child to go on milk with the Quinine is when fever is about". She remained ill for again on 28 August 1825, "Isabella continue the quinine child the quinine," and the same on 29 August 1825. Hospital notes do not reveal the outcome of Isabella’s pregnancy. Modern medical researchers note pregnant women infected with malaria usually have more severe symptoms and outcomes with higher rates of miscarriage, intrauterine demise, premature delivery, low-birth-weight neonates, and neonatal death.29

28 David W. Blight Frederick Douglas Prophet of Freedom (Simon &Schuster New York 2018), 1

Edward Fitzgerald to A.P. Upshur 18 October 1841 Department of the Navy, Officers Letters, RG 45 NARA

Hershel Parker Herman Melville A Biography Volume 1, 1819 -1851 (The Johns Hopkins Press Baltimore 1996), 293

John G.M. Sharp The Ship Log of the frigate USS United States 1843- 1844 and Herman Melville Ordinary Seaman 2019, pp3-4 accessed 9 September 2019 http://www.usgwarchives.net/va/portsmouth/shipyard/usunitedstates-hmelville

29 John G. Sharp Gosport Naval Hospital Staff in 1834 http://www.usgwarchives.net/va/portsmouth/shipyard/nnysharp10.html

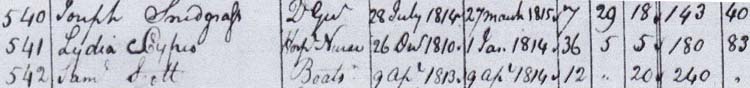

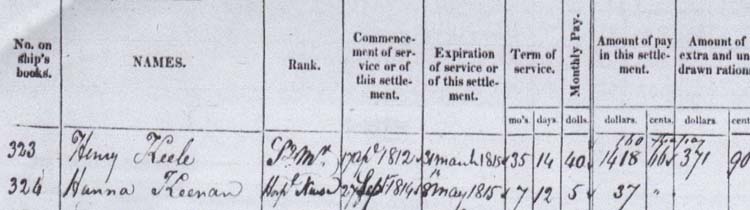

Two nurses, Lydia Cypris and Hanna Keenan, served in the Gosport Naval Hospital, during the War of 1812.

Lydia Cyris, Hospital Nurse, 26 Oct 1810 to 1 Jan 1814

Source: Miscellaneous Records of the Navy Department, 1803 -1859, Payrolls 1812 -1815,

"Payroll of Officers, Petty Officers, Seamen &c, &c on Norfolk Station," roll 0201, p. 13, no.541,

Lydia Cypis RG- 45. National Archives and Records Administration Washington, DC

Hanna Keenan, Hospital Nurse, 27 Sept 1814 to 18 May 1815

Source: Miscellaneous Records of the Navy Department, 1803 -1859, Payrolls 1812 -1815,

"Payroll of Officers, Petty Officers, Seamen &c, &c on Norfolk Station," roll 0201, p. 9, no. 324,

Hanna Keenan, RG- 45, National Archives and Records Administration Washington, DC

Who were the slaveholders? For the most part we have only limited glimpses, one who later gained notoriety stands out. The 1826 muster reflects Isabella Cooper’s wages were paid to wealthy Norfolk resident and naval purser Edward Fitzgerald USN (1785-1857). As a purser Fitzgerald was able to accumulate wealth and afford homes in both Georgetown D.C. and Norfolk Virginia. Like many naval officers Fitzgerald was a slaveholder with three enslaved males and four females residing with the family in Norfolk. In October 1844 the long standing practice of enrolling an enslaved man into naval service made Fitzgerald a brief celebrity. In October 1841 with the written consent of the Secretary of the Navy, he had entered his "servant" (slave) Robert Lucas as a landsman (in reality his personal steward) on board the frigate United States and collected Lucas nine dollars per month wages. After a long Pacific voyage in 1844, the United States anchored in Boston. While there, Lucas made a bid for freedom and with help of two white shipmates, and was able to acquire a writ of habeas corpus and a subsequent favorable ruling. This important case Commonwealth vs. Edward Fitzgerald re Robert Lucas 1844 became a precedent in the naval service, effectively barring enslaved individuals as seamen.

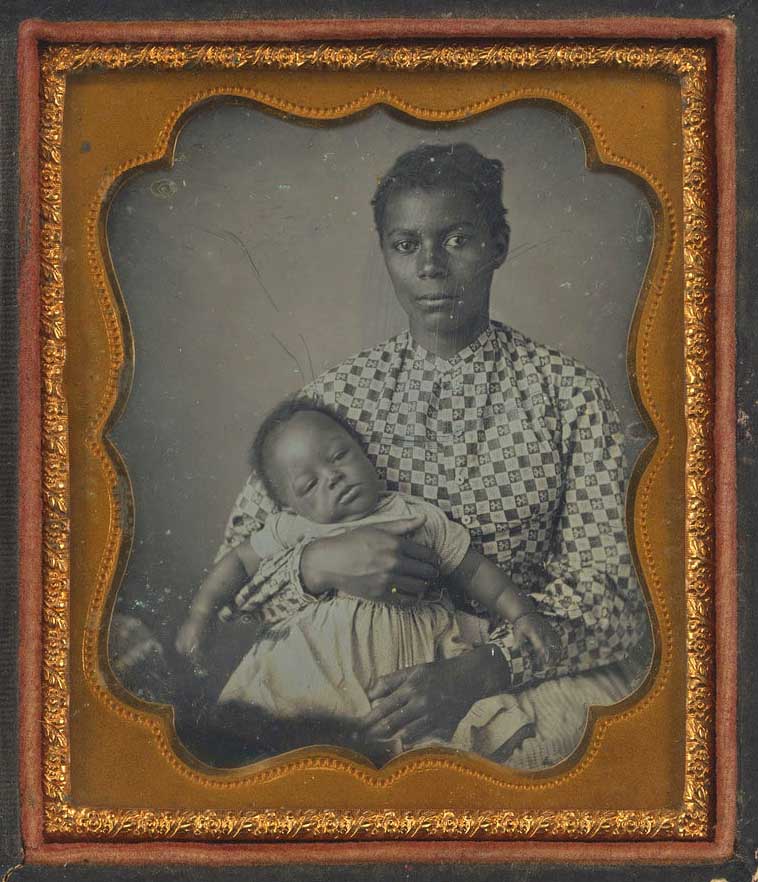

Sporadically we are given a more revealing glimpse of these enslaved workers. One such worker was Fanny Ballott. Fanny, a washer woman or laundress, is given prominent mention in the 1825-1826 files. She may have been housed somewhere with her children on the hospital grounds. Her surname Ballot is found the Gosport Navy Yard muster and payrolls,beginning in January 1825, where she is enumerated as employee no. 5, with her full name given as Fanny Ballott and occupation as washer. Likewise she is enumerated as employee number 34 on the hospital payroll for 1 January to 31 to December 1828. Her wages for the year were listed as $125.10 or $10.43 per month.30 Like the other women, her wages were collected by a slaveholder or designee. George Reed, the Gosport Naval Hospital steward, repeatedly signed for Ballot’s wages.

30 Schantz-Dunn J, Nour NM. Malaria and pregnancy: a global health perspective. Rev Obstet Gynecol. 2009; 2(3): 186-192.

Daguerreotype unidentified African American woman circa 1860

Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and CultureWhile the hospital workers signed for their wages with an X, some may have been literate. Literate blacks in the Norfolk like George Teamoh were wary of disclosing literacy. Educated blacks were often the subject of white suspicion for potentially aiding or abetting runaways by forging freedom papers, for transmitting abolitionist ideas or provoking insurrection like Nat Turner who had "learned to read and write."31 In the late 1830s Teamoh began to keep a journal to record "what transpired in this City and the Vicinity. In 1839 that whole year, I carried to record every hour of sun-shine, rain, cloud and thunder storm, marriages, births and deaths; distinguished visitors; ministers of the Gospel and where they hailed from; ... Indeed I put everything that ear could hear and eye could see or hand might reach, under contribution to serve my ends." Unfortunately, these early journals have not survived. Teamoh was justly proud of his hard-won literacy and on the front cover of six of eighteenth school exercise books that he penned his autobiographical manuscript, he carefully wrote, "written by himself." His literacy quickly marked him out, as other blacks requested he write or read for them, but he quickly found his literacy made many whites uneasy or suspicious.32 Literacy among African Americans was a prized and treasured possession.

31 Slave Narratives "The Confessions of Nat Turner" edited William L. Andrews and Henry Louis Gates Jr. (Library of America: New York 2000), 250

32 Teamoh 75-78

In the hospital case files we learn Fanny Ballott was both pregnant and suffering from malaria. An entry for 2 September 1825 states "Fanny in labor, send for a midwife." Another entry from the case file for 3 September reads "Fanny in the hands of the Midwife…" Dr. Williamson’s response was typical of the era as the presence of a black midwife was thought to benefit not only the bondswoman but the slaveholder.33 Dr. Williamson clearly knew this midwife and probably had used her services for other births. Black midwives delivered both black and white children.34 Usually Dr. Thomas Williamson and other administrators wrote the polite euphemism "servant" or "attendant" for their enslaved workers. However on the entry for 4 September 1825, all subterfuge is dropped, "Fanny discharged from the Hospital and sent to her owner." The medical care and attention that slaves such as Fanny and Isabella received was based not on charity but on their worth as property. By the 1830 census the Virginia population totaled 1,211,405, of which 469,757 were enslaved or 38.78 % of the population.35 Slavery had come to represent a substantial economic investment. Slaveholding represented both profit and status. Each child born to an enslaved mother became the slaveholder’s property and increased to their wealth and prominence. Slaves were costly the $400 average slave price in 1850 however can also be thought of as a signaling device of status in a period where the annual per capita income was about $110.36 In Virginia the child of a slave mother was by definition a slave, consequently slaveholders valued healthy young children as a source of future income.

33 V. Lynn Kennedy Born Southern: Childbirth, Motherhood and Social Networks in the Old South (Johns Hopkin University Press: Baltimore2010), 67

34 Savitt 182

35 The Library of Virginia state census figures accessed 23 August 23, 2019 https://www.lva.virginia.gov/public/guides/SlaveryInVA.pdf

36 Samuel H. Williamson and Lewis P. Cain Measuring Slavery in 2016 Dollars accessed 23 August 2019 https://www.measuringworth.com/slavery.php

Slaveholders concern with their "property" led to medical care for slaves leased to the federal government. In 1813 Washington Navy Yard was authorized to provide care for bondsmen leased to the navy yard. This care included emergency medical care provided at the Washington Naval Hospital and later extended to other naval hospitals. The Secretary of the Navy wrote to Dr. Edward Cutbush at Naval Hospital Washington, "It is however to be understood that if any Master or Laboring Mechanics or common laborers employed in the Navy Yard shall receive any sudden wound or injury, while so employed in the Navy Yard, he shall be entitled to temporary relief. But if the person sustaining such injury be a Slave, his master shall allow out of his wages a reasonable compensation for such medical and hospital care as he may receive and if the injury of disability shall be likely to continue, the master shall cause such Slave to be removed from the public hospital Stores."37

37 Secretary of the Navy, W. Jones to Dr. Edward Cutbush, 23 May1813 RG45 NARA

Gosport Naval Hospital Case file remarks by Dr. Thomas Williamson dated 4 September 1825

notating that washer" Fanny [Ballott] discharged from the Hospital and send to her owner.’

Isabella [Cooper] washer is listed as "for duty"Fanny and her workmate Isabella Cooper both suffered recurrent bouts of malaria, as hospital records reveal they were treated with quinine frequently. Quinine was the first effective treatment for malaria and came from the bark of cinchona tree, which contains quinine.38 The bark was dried, ground to a fine powder and mixed into a liquid (commonly wine) for drinking. The two enslaved women with their children remained a regular part of the early naval hospital.

38 Case Files for Patients at Naval Hospitals Register of Patients Naval Hospital Gosport volume 5 1818 -1823 NARA RG 54. References to Fanny Ballott being prescribed quinine are found April 5, 7, 8 and 26 1826. Isabella Cooper was given quinine on 25 and 31 August every two hours and again on 1 September 1825 with soup. Isabella Cooper returned to duty on 6 September 1825. Fanny Ballott was again treated on 6, 7, 8, 9 April 1826 with "quinine, arrow root and wine" and returned to duty 10 April 1826.

Laundress scrubbing clothes

( U.S. Army Center for Military History)The issue of the employment of enslaved labor rarely appeared in official correspondence. In 1830 however Dr. William P.C. Barton became the first head of the new hospital. Barton was known for his writing on naval medicine and administration.

William P.C. Barton, A Treatise Containing a Plan for the Internal Organization and Government of Marine Hospitals in the United States: Together with A Scheme for Amending and Systematizing the Medical Department of the United States Navy (1814)

In 1830 Dr. Barton chose toopenly question the practice of paying naval officers for the rations used to feed their slaves. Barton was not an abolitionist, nor is there any indication he was opposed to slavery. Prior to his assignment to Gosport, Dr. Barton had made a reputation for promoting economy at Philadelphia. As he later explained to the Secretary of the Navy, on taking command in Norfolk he found a "system of fraud and peculation that crept unnoticed by the surgeon [Dr. Thomas Williamson] or the Commandant [Commodore James Barron]" and he went on to "request Commodore Barron to discharge the (-) ward attendant, the washerwomen, the messenger boy and servant…"39 In his 23 November 1830 letter to the Secretary of the Navy John Branch, Barton wrote, "Assistant Surgeon James Cornick lives there [the hospital] at the table kept at public expense for officers, patients of the institution and himself. This arrangement is indefensible for the effective regulation of the sick or invalid officers."40 Dr. Williamson and Dr. Barton remained at odds throughout their careers. Dr. Williamson charged Barton withholding necessary articles of medicine and the ordinary comforts from sick officers & men under my charge…" Williamson then added his dismay at Dr. Barton’s "continuous efforts to rearrange well-arranged matters…," perhaps a hint at the two men’s disagreements over the employment of slaves on the public payroll.41

39 Holcomb 166 and 177

40 William P.C. Barton to John Branch 23 November 1830, Officers Letters to the Secretary of the Navy volume 141-142 NARA RG 45

41 "Officers Letters" Thomas Williamson to A. Thomas Smith, Acting Secretary of the Navy, NARA M148 RG 45 Volume 297 -298 dated 17 June 1843

How aware Dr. Barton was that Dr. Williamson and Commodore Barron employed their slaves at the hospital and shipyard is hard to determine. Barton assumed the washers and the other workers were able to keep their wages, "All these pretend to support themselves but I have good reason to believe this was at least half done at the expense of the hospital."42 Whatever his intention, his claim of fraud in the purchase of hospital food stuffs being far in excess of that required by the patients (with the surplus provisions used to feed the enslaved workers) quickly raised the hackles of the medical staff. In his 15 November 1830 letter to the Secretary of the Navy, he further recommended putting the hospital laundry out as piecework.43 Dr. Barton remained at the hospital just six months

42 Holcomb 170-171

43 Holcomb 168-170

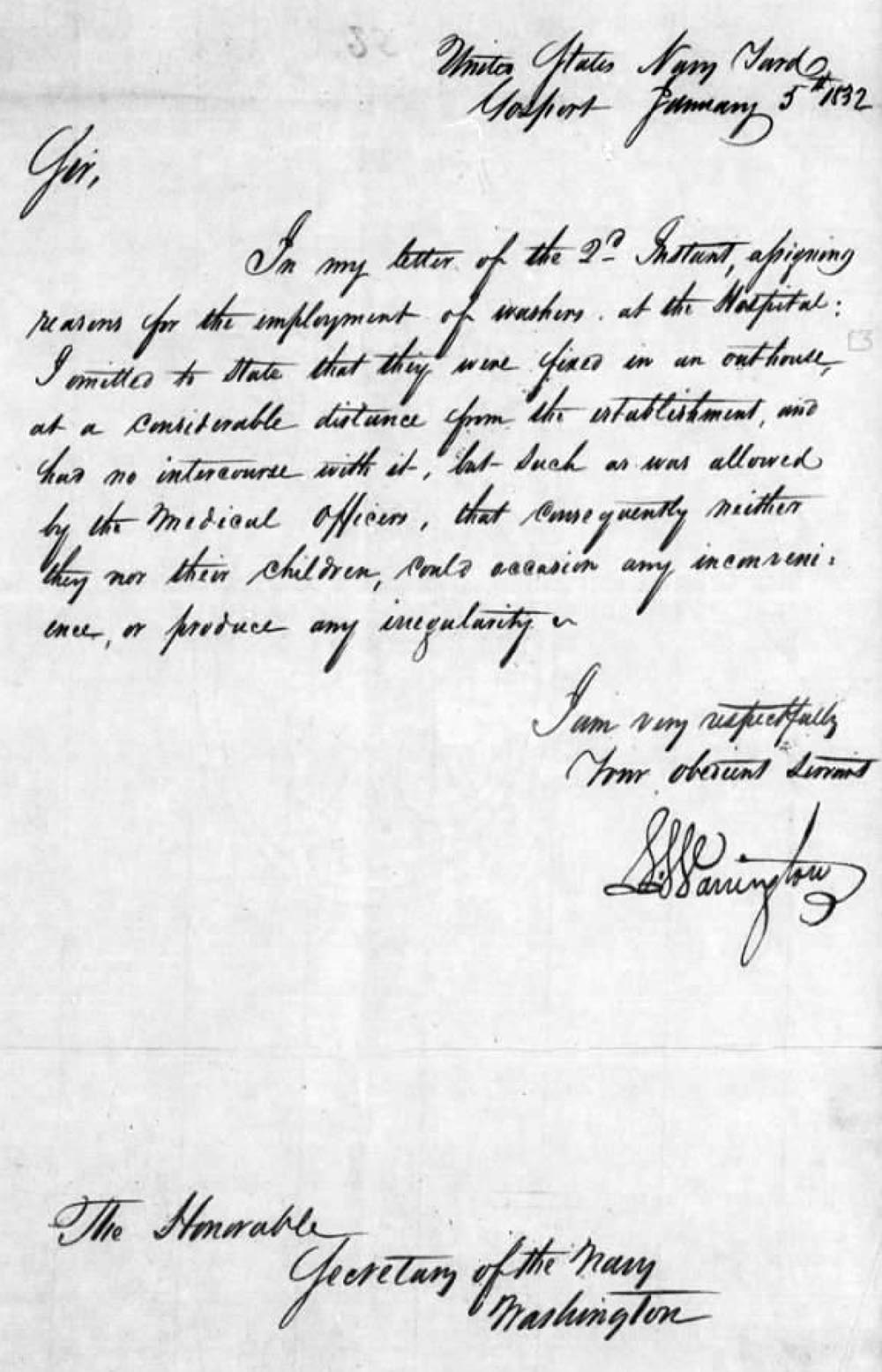

Commodore Barron’s successor Lewis Warrington moved to retain the enslaved washers. He wrote (2 January 1832) to the Secretary of the Navy to confirm the decade long practice at Gosport and that "the employment of Washers for whom the estimates of last year provided (as they had done the previous year) took place at the suggestion and on the recommendations of the Hospital Surgeon who believed it was a more economical and better mode than the one existing…knew for ten years that this mode had been pursued without complaint or representation against it….As the Washers are paid out of an appropriation for pay, I supposed that if a change was authorized by the Department, the Commander of the Yard would be apprised of it…"44

44 "Captains Letters" Lewis Warrington to the Secretary of the Navy, dated 5 January1832 NARA M125 RG260 Volume 166, letter number 6

In his follow-up letter of 5 Januarys 1832 to the Secretary of the Navy, Warrington clarified the hospital slaves separate sleeping quarters. "[In] assigning reasons for the employment of Washers at the Hospital, I omitted to state that they were fixed in an outhouse at a considerable distance from the establishment and had no intercourse with it, but such as was allowed by the medical officer, consequently neither they nor their children could occasion any inconvenience or produce any irregularity."45

45 "Captains Letters" Lewis Warrington to the Secretary of the Navy, dated 5 January1832 NARA M125 RG260 Volume 166, letter number 25

Letter 5 January 1832 Commodore Warrington

To Secretary of the Navy (enlarge in browser)Despite official denial, enslaved labor continued at the Norfolk and at other locations. So called "gentlemen’s agreements" persisted, and slaves were stealthily hired and placed on the books as freemen. Congressional oversight grew and in 1842, the Congress, required government agencies to report the number of slaves they hired. The Secretary of the Navy, A.P. Upshur, in reply to a question from the Speaker of the House of Representatives, "There are no slaves in the Navy , except only a few cases in which officers have been permitted to take their personal servants instead of employing them from crews. There is a regulation of the Department against employment of slaves in the general service" Upshur went on to carefully note "neither regulations nor usage excludes them as mechanics, laborers, or servants in any branches of the service where such a force is required."

On 6 December 1845 Commodore Jesse Wilkinson commandant of the Navy Yard confirmed this was also the long standing practice at Norfolk. In his letter to the Secretary of the Navy, George Bancroft Wilkinson stated "a majority of them [blacks] are negro slaves, and that a large portion of those employed in the Ordinary for many years, have been of that description, but by what authority I am unable to say as nothing can be found in the records of my office on the subject." Wilkinson’s acknowledgment is crucial for his startling admission reveals how this deceptive practice had spread to nearly every facet of the shipyard. George Teamoh who worked at the Norfolk Navy Yard Ordinary in the 1840s, spoke for many when he pointed to the unpleasant but undeniable truth, "The government has patronized, and given encouragement to Slavery to a greater extent than the great majority of the country has been aware. It had in its service hundreds if not thousands of slaves employed on government work"

It is important to remember that, "The vast majority of the people enslaved over the course of the Yard’s history died as they lived - in bondage."

Sources:

Secretary of the Navy, A.P. Upshur, to the Speaker of the House, 10 August 1842, Exec. Doc. No.282, 27th Congress, 2nd Session

Wilkinson to Bancroft 6 December 1845 NARA M125 "Captains Letters" Letter Received from Captains 1805 -1885, 1 Nov 1845 – 31 Dec 1845, letter number 84, 1-2

Thomas Hulse, "Military Slave Rentals, the Construction of Army Fortifications, and the Navy Yard in Pensacola, Florida, 1824–1863," Florida Historical Quarterly, 88 (Spring 2010), 497–539

Walter Johnson Soul By Soul Life Inside the Antebellum Slave Market Harvard UniversityPress: Cambridge Mass. 1999,10.

The table below arranged chronologically 1815-1842 was constructed from Gosport (Norfolk) Naval Hospital’s surviving musters and payrolls found within the so called Miscellaneous Records of the Navy Department. These documents include the 1834 unique "List of the Officers, Nurses, Servants &c attached to U. S. Naval Hospital near Portsmouth Virginia, and shewing the date of the commencement of their services and the compensation allowed to each".

In transcribing all data for the table, I have included the full name of the worker as listed. This includes variant spelling e.g. Fanny Ballot, Fanny Ballet, Isabella Cooper AKA Arabella Cooper, Delilah Bradford AKA Delia Bradford etc. Job titles are given as recorded, e.g. cook, hospital cook etc. Pay information is typically provided for the month, not the quarter. Where possible to discern a signature I have included the name of the individual signing for the enslaved worker.

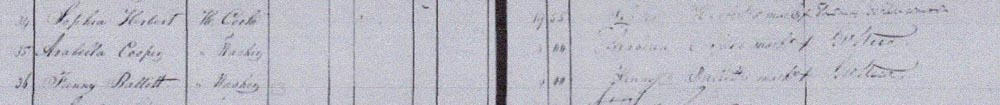

Detail from Gosport Navy Yard 1829 muster, no. 34 Sophia Herbert cook, no. 35 and washers Arabella Cooper no. 36 Fanny Ballott no.37.

The women’s wages were signed for by slaveholders Thomas Williamson and Geo Reed.

In 1829 Dr. Williamson was hospital surgeon George Reed the hospital steward.Norfolk (Gosport) Naval Hospital Female Employees 1810 -1842

Name Lydia Cypris

1 Jan 1814Hanna Keenan

18 May 1815Delilah Bradford Delilah Bradford Lydia Smith Fanny Cook Delilah Bradford Lydia Henson Lydia Henson Lydia Smith Lydia Smith Fanny Cook Fanny Cook Delilah Bradford Lydia Smith Fanny Cook Delia Bradford Delilah Bradford Isabella Cooper Lydia Smith Molly Lakey Delilah Bradford Isabella Cooper Molly Lakey Fanny Ballott Arabella Cooper Molly Lakey Isabella Cooper Mollie Lecker [Molly Lecker] Fanny Ballott Delilah Bradford Arabella Cooper Fanny Ballott Molly Lecker Sophia Herbert Arabella Cooper Fanny Ballett Sophia Herbert Arabella Cooper Fanny Ballott Sophia Herbert Isabella Cooper Fanny Ballott Lydia Logue Sophia Herbert Madeline Flanders Isabella Cooper Sophia Herbert Hannah Wheeler Sophia Herbert Hannah Wheeler Isabella Cooper Mary Jones Mary Russell Mary Russell Sophia Herbert Isabella Cooper Hannah Wheeler Mary Ponse Sophia Herbert Isabella Cooper

1836

116/6

Muster

Washer

Hannah Wheeler

1836

116/7

Muster

Assistant Cook

Mary Jones

1836

116/11

Muster

Washer

Mary Russell

1836

116/17

Muster

Nurse

Sophia Herbert

1 Apr 1841 to 31 May 1841

43/2

Payroll

Cook

12.24

Hannah Wheeler

1 Apr 1841 to 31 May 1841

43/5

Payroll

Asst. Cook

12.24

Esther Blow

1 Apr 1841 to 31 May 1841

43/11

Payroll

Washer

12.20

Ann Powers

1 Apr 1841 to 31 May 1841

43/15

Payroll

Nurse

18.30

Sophia Herbert

1 May 1841 to 31 May 1831

43/3

Payroll

Cook

12.24

Sophia Herbert

1 Oct 1842

219/2

Muster

Cook

Isabella Cooper

1 Oct 1842

219/4

Muster

Washer

Esther Blow

1 Oct 1842

219/10

Muster

Washer

Ann Powers

1 Oct 1842

219/ 13

Muster

Nurse

Sophia Herbert

1 Oct 1842 to 31 Dec 1842

211/ 2

Payroll

Cook

12.00

Benj. W. Palmer

Isabella Cooper

1 Oct 1842 to 31 Dec 1842

211/4

Payroll

Washer

8.00

Benj. W. Palmer

Hannah Wheeler

1 Oct 1842 to 31 Dec 1842

211/5

Payroll

Cook

8.00

Benj. W. Palmer

Esther Blow

1 Oct 1842 to 31 Dec 1842

211/10

Payroll

Washer

8.00

Benj. W. Palmer

Ann Powers

1 Oct 1842 to 31 Dec 1842

211/11

Payroll

Nurse

10.00

Benj. W. Palmer

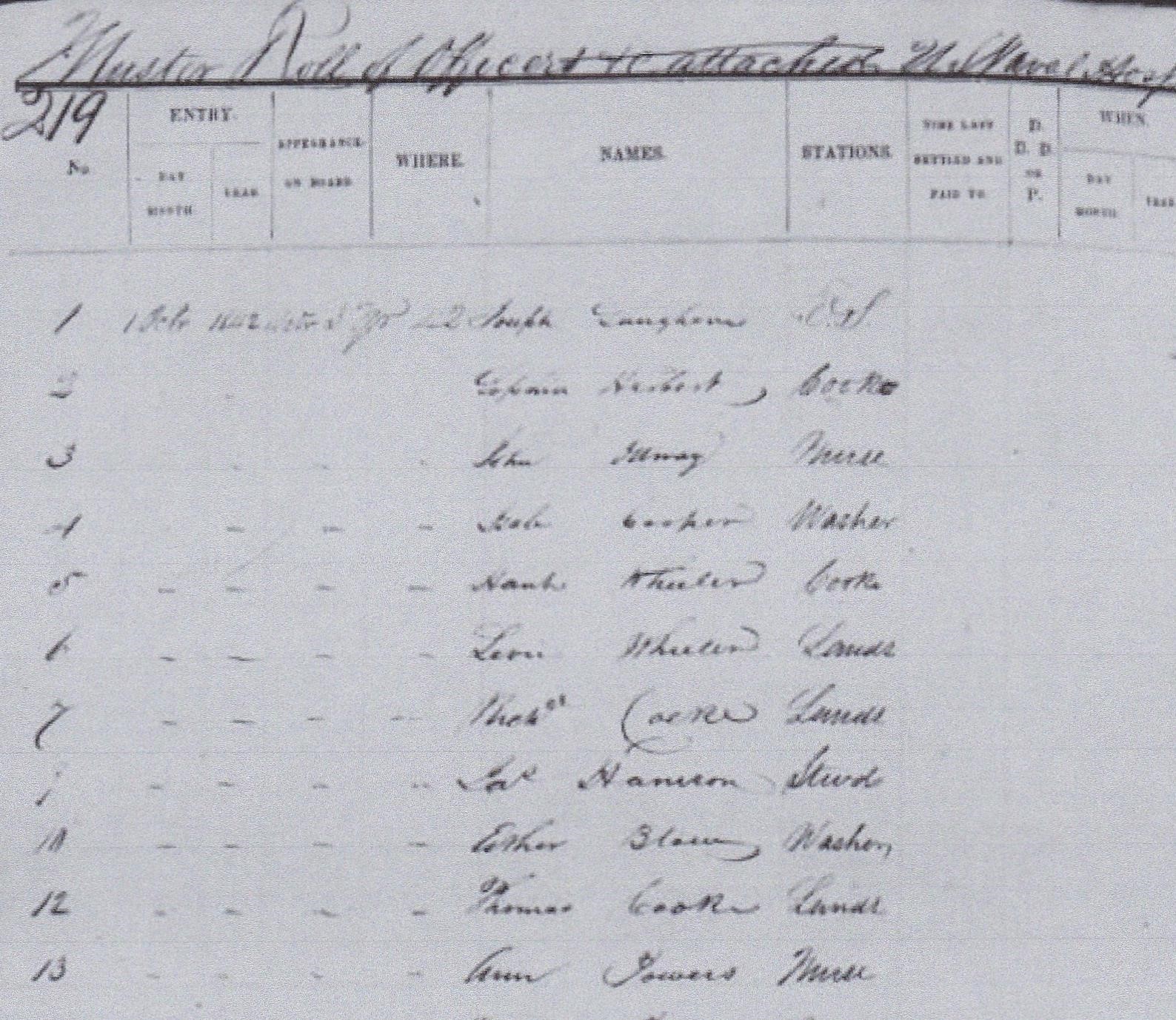

1842 muster of the Gosport Naval Hospital staff, no. 2 Sophia Herbert cook, no. 4.Isabella Cooper washer, nurse no.5

Hannah Wheeler cook no. 6 Levi Wheeler landsman, is almost certainly Hannah Wheeler spouse no. 10, Esther Blow washer and no. 13 Ann Powers NurseBibliography:

Richard C. Holcomb A Century with Norfolk Naval Hospital (Printcraft Publishing: Norfolk 1930), 170-171

Thomas Hulse, "Military Slave Rentals, the Construction of Army Fortifications, and the Navy Yard in Pensacola, Florida, 1824–1863," (Florida Historical Quarterly, 88, Spring 2010), 516

Harold D. Langley’s 1995 A History of Medicine in the Early U.S. Navy (Johns Hopkins Press: Baltimore 1995), 13, 320-321George Teamoh God Made Man Man Made the Slave The Autobiography of George Teamoh editors F.N. Boney, Richard L. Hume and Rafia Zafar Mercer University Press: Macon 1990, 84

Ernest E Dibble Antebellum Pensacola and the Military Presence Pensacola News Journal: Pensacola 1974,62

John G. Sharp Documents Reflecting African Americans in Slavery and Freedom in the District of Columbia 2010. Accessed 20 August 2018 http://genealogytrails.com/washdc/slavery/slaveryintro.html

* * * * * *

John G. "Jack" Sharp resides in Concord, California. He worked for the United States Navy for thirty years as a civilian personnel officer. Among his many assignments were positions in Berlin, Germany, where in 1989 he was in East Berlin, the day the infamous wall was opened. He later served as Human Resources Officer, South West Asia (Bahrain). He returned to the United States in 2001 and was on duty at the Naval District of Washington on 9/11. He has a lifelong interest in history and has written extensively on the Washington, Norfolk, and Pensacola Navy Yards, labor history and the history of African Americans. His previous books include African Americans in Slavery and Freedom on the Washington Navy Yard 1799 -1865, Morgan Hannah Press 2011. History of the Washington Navy Yard Civilian Workforce 1799-1962, 2004.

https://www.history.navy.mil/content/dam/nhhc/browse-by-topic/heritage/washington-navy-yard/pdfs/WNY_History.pdf

and the first complete transcription of the Diary of Michael Shiner Relating to the History of the Washington Navy Yard 1813-1869, 2007/2015 online:

https://www.history.navy.mil/research/library/online-reading-room/title-list-alphabetically/d/diary-of-michael-shiner.html

His most recent work includes Register of Patients at Naval Hospital Washington DC 1814 With The Names of American Wounded From The Battle of Bladensburg 2018,

https://www.history.navy.mil/research/library/online-reading-room/title-list-alphabetically/r/register-patients-naval-hospital-washington-dc-1814.html

The last three works were all published by the Naval History and Heritage Command. John served on active duty in the United States Navy, including Viet Nam service. He received his BA and MA in History from San Francisco State University. He can be reached at sharpjg@yahoo.com* * * * * *

Norfolk Navy Yard Table of Contents

Birth of the Gosport Yard & into the 19th Century

Battle of the Hampton Roads Ironclads