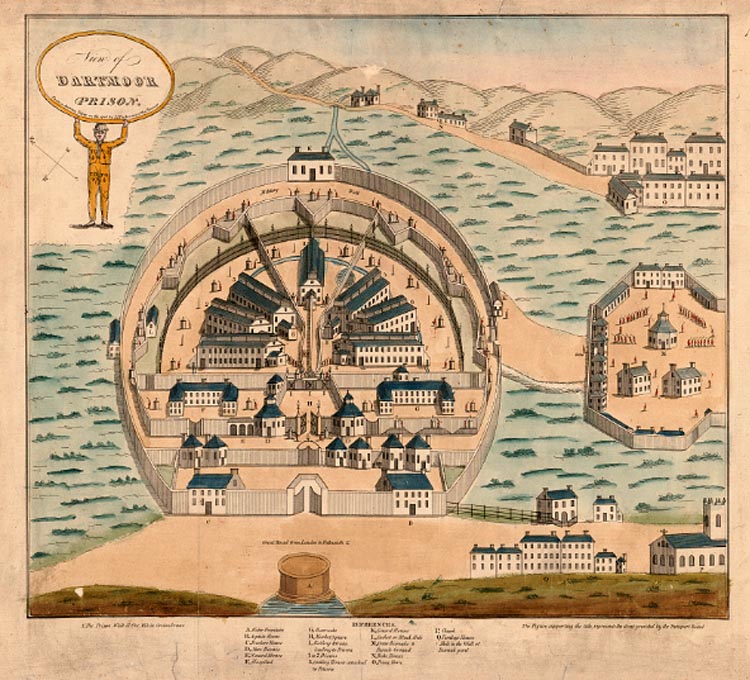

Dartmoor Prison 1815

American Prisoners of War in Dartmoor Prison during the War of 1812

by John G M Sharp

Introduction

Today most people remember HM Dartmoor Prison, if at all, either from having read or likely seen film versions of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Hound of the Baskervilles and Charles Dickens' Great Expectations with desperately fleeing murderer Abel Magwitch. For much of its long history, this prison became a byword for despair.

From the spring of 1813 until March 1815, the newly constructed (1809) HM Dartmoor Prison dominated the vast Devon landscape and held American seafarers in poor conditions. The prison complex was located 1,430 feet above sea level and surrounded by two high granite walls which govern a large area of the treeless ancient moorland, cloaked in fog or swept by winds and driving rain.1 During the course of the War of 1812, the prison held 6,553 American prisoners of war.1. . Guyatt, Nicholas, The Hated Cage: An American Tragedy in Britain's Most Terrifying Prison (Basic Books, New York, 2022), p. 9; Hickey, Donald R. The War of 1812: A Forgotten Conflict (University of Illinois, Chicago, 2012), p. 312.

The majority of those held in Dartmoor Prison were the crews of American privateering vessels. These seafarers manned privately owned merchant ships that, in wartime, that were armed by their owners and licensed by the government to attack the maritime trade of the enemy. Privateers profited by the sale of ships and cargoes they captured. The privateering business involved ownership consortiums to split investment costs and profits or losses, and a group contract to incentivize the crew, who were paid only if their ship made profits. A sophisticated set of laws ensured that the capture was “good prize,” and not fraud or robbery.2

2 Leiner, Frederick C., Yes, Privateers Mattered, March 2014, Naval History Magazine, Volume 28, Number 2.

As Secretary of the Navy William Jones reminded his officers,"The enemy’s commerce is our true game, for there he is indeed most vulnerable.”* American privateering vessels expanded this dictum as they hunted British ships leaving United Kingdom ports and drove up insurance rates for merchant ships sailing from the ports of Liverpool to Halifax by 30%. Throughout the war American privateers captured and harassed British commerce in the Irish Sea where insurance rates for vessels trading between England and Ireland rose an unprecedented 13%. As a result by 1814 the British Navy was forced to convoy merchant ships. American privateers in search of prey operated around the globe particularly in the Caribbean. Such vessels usually fled from the larger better-armed British war ships, and, when unable to escape, often surrendered. On occasion, however, they could be formidable opponents.

* The Naval War of 1812: A Documentary History Volume II, editor William S. Dudley (Naval Historical Center, Washington DC., 1992), p. 297.

The second of the category of prisoners were impressed (forcibly conscripted) American merchant seaman. Among these were sailors discharged from British vessels that had refused to swear allegiance to the King and or continue in his service.3, 4

3. Guyatt, p. 12. Taylor, Alan, The Civil War of 1812: American Citizens, British Subjects, Irish Rebels and Indian Allies (Vintage Books, New York, 2010), pp. 364-365.

4. For an estimate of American seamen pressed into the Royal Navy during period 1793-1812, see "The Misfortune to Get Pressed 1793-1812." Joshua J. Wolf. Wolf estimates a total of 15,835.

https://scholarshare.temple.edu/bitstream/handle/20.500.12613/4048/TETDEDXWolf-temple-0225E-12189.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=yThe last category is the 250 U.S. Navy sailors in Dartmoor Prison. The first of these arrived with the crew of the Brig USS Argus in September and October 1813.

This article, the first of two parts, comprises a brief overview of Dartmoor Prison during years 1812-1815, with a discussion of the differing reception and treatment afforded each category of Americans imprisoned therein during the course of the war.

John G. M. Sharp 24 November 2022

Acknowledgements

This history would not be possible without the many scholars who have begun to reexamine the history of the War of 1812, and to the libraries and librarians on both sides of the Atlantic who have carefully catalogued and preserved the naval and maritime records and documents this article is based on. Much of this present article is based on my research in the British National Archives, General Entry Books of American Prisoners of War at Dartmoor. Today this splendid collection is one of our best and most unique sources starting pointfor information about the lives of ordinary American sailors imprisoned during the War of 1812. I have supplemented this with additional information found in Seaman’s Protection Certificates, United States Navy payroll and muster documents and contemporary newspaper accounts, all found in the National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, DC.

All historians depend on and benefit from the work of others who have gone before. First, I owe grateful thanks to Professor Nicholas Guyatt whose recent (2022) The Hated Cage: an American Tragedy in Britain's Most Terrifying Prison, brilliantly narrated and synthesized voluminous maritime and prison records into a coherent and fascinating history and yet still found time to answer my many questions.

A special thanks to my friend Donna Bluemink for her editorial help, insightful assistance and kind advice.

In the course of my research, I have utilized the late Ira Dye’s wonderful Prisoner of War Data Base numerous times. Captain Dye compiled a database of more than 17,000 prisoners of war taken during the War of 1812, now hosted by the USS Constitution Museum online https://ussconstitutionmuseum.org/ira-dye-prisoner-of-war-database. His extensive data base, research and insights contributed greatly to my understanding of American seafarers at Dartmoor Prison.

I also found Simon P. Newman’s (2003) splendid Embodied History: the Lives of the Poor in Early Philadelphia insightful. Like the great E.P. Thompson, Newman has chosen to write with care, respect and empathy about the lives of the working class. Newman was my model for the use of the Seaman's Protection Certificates (issued to American seamen from 1796-1818) to examine the lives of American seamen. Like Newman, I found these documents reveal these mariner’s lives were often harsh, dangerous and risk of injury or death loomed ever large.

My gratitude and appreciation has grown for the website War of 1812 Privateers https://www.1812privateers.org/index.html. This site hosts a wide body of information about both American and British privateers with listings and explanations of American prisoners of war held in the United Kingdom plus British subjects held in the United States.Impressed Seafarers in HM Dartmoor

Impressment, colloquially "the press" or the "press gang", is the taking of men into a military or naval force by compulsion with or without notice.5 Many of the impressed sailors were Americans citizens taken off merchant vessels in Britain and foreign ports. For example, in Liverpool harbor on 3 November 1813, the Royal Navy forcibly detained seven American seamen. As they refused to serve in the British Navy, they were held in Dartmoor Prison until 26 April 1815.6

5. Hickey, Donald R. The War of 1812: A Forgotten Conflict. ( Urbana; Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1989), p. 44.

6. Dartmoor General Entry Books for American Prisoners of War, ADM 103/87, 88, 89, 90 and 91 British National Archives, see Dartmoor prisoners numbers 757-763.

British officers inspect a group of American sailors for impressment

into the British navy, ca. 1810, drawing by Howard Pyle.While the Royal Navy impressed American merchant sailors, the majority of those forcibly conscripted were actually citizens of Great Britain and other countries. Those liable to impressment were "eligible men of seafaring habits between the ages of 18 and 55 years.

Message in a bottle, William Banks, an impressed American seaman, pleas for help

In July 1813 a stroller forwarded a message he had found in a bottle by the Thames River addressed to James Banks at Hampton, Virginia, regarding his brother William Banks, a seaman on the famed HMS Ramillies. The HMS Ramillies was a 74-gun third rate ship of the line of the Royal Navy, launched on 12 July 1785. In August 1812, Sir Thomas Masterman Hardy had taken command of Ramillies. Commodore Hardy (later Vice Admiral) had fought with Admiral Nelson at the Battle of Trafalgar.

On receiving the message about his brother William, James Banks sent a letter requesting the assistance to Congressman Thomas Newton and another to American Representative in London, James Mason requesting help to secure William a new seaman’s protection and his release.7

7. United States War of 1812 Papers 1789-1815 of the Department of State, 1789-1815; General Records of the Department of State, Record Group 59; National Archives, Washington, DC, see p. 91.

James Banks in his 5 July 1813 letter expressed his surprise to Congressman Thomas Newton about the letter "which came …in such a miraculous way".8

8. Thomas Newton Jr. (1768 -1847) was a United States Congressman from 1801-1833 representing the Hampton, Virginia, area.

Later Congressman Newton in his 10 July 1813 reply assured James Banks he was gathering the requisite information and concluded, "I am persuaded your exertions will be made to liberate an unfortunate American citizen from the fangs of British Myrmidons."

William Banks was born in Hampton, Virginia, about 1784 and was 29 years of age, standing 5’7½" and had been a seaman for nearly a decade. William’s message related he had been forcibly impressed into the Royal Navy, possibly while part of the crew of a merchant vessel in London. William Banks had been issued two earlier protection certificates. The first issued in London on 19 March 1806 at the American consulate and the other on 23 July 1806 in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, identifying marks of a foul anchor tattoo and a scar on his right hand. Banks was in the crew of HMS Ramillies then at Chatham, England. Banks desperately needed a copy of his protection certificate to prove his citizenship. William made his X on his certificate issued in Philadelphia in 1806, so another sailor probably helped write the message secured in the bottle. It is not known if any official efforts resulted in William Banks release.

John Howell Dartmoor Prisoner number 2721. Seaman John Howell was in the crew of a merchant vessel Eclipse when he was forcibly impressed into the British Navy in 1810. On 1 July 1813 Howell wrote to the State Department from the prison ship HMS Samson, begging for their assistance. In his letter he explained his "Protection" or "Seamen Protection Certificate", also "Sailor's Protection Paper", were taken. Protection papers provided a description of the sailor and showed American citizenship. Such papers were issued to American sailors to prevent them from being impressed on British men-of-war, during the period leading to and after the War of 1812.9 He claimed his papers identifying him as an American citizen had been taken and he needed a replacement to secure his release.

9. Sharp, John G. M. American Seamen’s Protection Certificates & Impressment 1796-1822. http://www.usgwarchives.net/va/portsmouth/shipyard/sharptoc/aspc&i.html

My last Protection was granted to my mother Mrs. Margaret Flinn, Philadelphia, in 1810 and was destroyed by the British the same year when I was placed on board the Polaris sloop of war at Smyrna out of the [merchant ship] Eclipse, captain Robinson. My marks: scar on my right hand, scar on my left foot, dark complexion, brown hair, pitted, smallpox, five feet eleven ½ inches high. I was born in the City of Philadelphia.

John Howell, prisoner, on board HMS Prison Ship SamsonDespite his plea, John Howell spent the rest of the war as a prisoner, first at Chatham and later in Dartmoor. What he needed and desperately sought was his seaman's protection certificate; (see above) issued 16 May 1810. Howell was, as he stressed, an American citizen born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Like the majority of seafarers, Howell, by his X was probably not literate and had a fellow POW write his appeal to James Monroe. Sadly, neither the State Department nor Ruben Beasley, the American representative in London, was much help to POW’s. Beasley, in fact, was despised and burned in effigy by the prisoners.10

10. Guyatt, pp. 262-3.

U.S. Navy Sailors in Dartmoor Prison

The most notable prisoners in Dartmoor were the crew of the brig USS Argus whose spectacular voyage in the summer and fall of 1813 included daringly raids on merchant shipping in British home waters for a month. Between 8 October 1812 and 3 January 1813, the American brig captured six valuable prizes and eluded an entire British squadron during a three-day stern chase. Through clever handling, of her Captain William Henry Allen, the Argus even managed to take one of her prizes as she was fleeing from the overwhelmingly superior British force.11

11. Petrie, Donald, (Summer 1994) "Forbidden Prizes" The American Neptune, 54 (3): pp. 167–168.

HMS Pelican v USS Argus, 14 August 1813 by Thomas Whitcombe, 1815,

Naval History and Heritage CommandThe Argus had departed New York with a complement of 151 men. At the time of the engagement with HMS Pelican, Argus crew, due to the manning of several prizes had been reduced to 131, a 121 of whom were fit for duty. In the Irish Channel on 14 August 1813, her luck changed for the worse. The heavier and somewhat larger British Brig HMS Pelican intercepted her. After a sharp fight during which Argus lost 6 seamen killed in action, two midshipmen, the carpenter, and three seamen all mortally wounded.12 In addition her first lieutenant and 5 seamen were severely wounded plus 8 others slightly wounded. As Captain, Master Commandant, William Henry Allen USN, lay mortally wounded, after the battle his leg was later amputated.

12. The Naval War of 1812: A Documentary History Volume II, editor William S. Dudley (Naval Historical Center, Washington D.C., 1992), 223, n3.

The Journal of Surgeon John Inderwick, provides a graphic account her final battle (transcribed below) along with detailed list of the USS Argus killed and wounded.13

13. The Naval War of 1812: A Documentary History Volume II, editor William S. Dudley (Naval Historical Center, Washington D.C., 1992), 221.

August 14th Saturday St. Georges Channel

Early this morning came to action with a large Brig she captured us after an action of 45 minutes she proved to the PelicanThe following list comprehends the number of killed and wounded on board of our vessel as far as can be at present ascertained.

Mr. Wm. W. Edward – Midshipman. Killed shot in the head.

Mr. Richard Delphy – Midshipman Do [ditto] Had both legs nearly shot off at the knees he survived the action about 3 hours.

Joshua Jones – Seaman – Killed –

Geo. Gardiner – Seaman – His thigh taken off by a round shot close to his body he lived about ½ hour –

Jno. Finlay – Seaman – His head was shot off by a round shot at the close of the action –

Wm. Moulton [Knolton] - Seaman Killed.

Total 6

The following were wounded viz.

Wm H. Allen – Commander – His left knee was shattered by a cannon shot. Amputation of that thigh was performed about 2 hours after the action – an Anodyne [pain killing medicine] was previously administered - An Anodyne at night-

Lieut. Wm H. Watson – 1st Part of the Scalp on the upper part of the head torn off by a grape shot by grape shot – the bone denuded. It was dressed lightly and he returned and took command of the deck- now on board the Pelican

Mr. Colin McCloud – Boatswain – Received a severe lacerated wound on the upper part of the thigh, a slight one on the face and contusion on the right shoulder. Dressed simply with lint and roller Bandage –

Mr. James White – Carpenter- Shot near the upper part of the left thigh – bone fractured. Hemorrhage considerable – Dressed the wound with lint imbued with oil Olivar – Applied bandage and sprints - Anodyne at night has also an incised wound in the head – Dressing – Suture – Adhesive plaster & Double headed roller.

Mr. Joseph Jordan – Boatswains Mate Has a large wound through the left thigh the bone fractured and splintered – the back part of the right thigh carried away – Dressed with lint imbued with oil Olivar – gave large anodyne – repeated at night – Case hopeless -

Jno Young – Quarter Master- Received a severe shot wound in the left breast seemingly by a glancing shot. The integuments and part of the extensor muscles of the hand torn away – gave him an anodyne at night –

Francis Eggert – Seaman – Has a very severe contusion of the right leg with a small gunshot wound a little above the outer ankle no ball discoverable – Dressed the wound with lint & bandage & directed the leg to be kept constantly wet with Aq Veg Mineral – 3 hours after reception the leg swelled and very painful gave him an anodyne – Proposed Amputation but he would not consent. This morning the leg excessively tense –swelled – desiccated - and of a dark color about the outer ankle – Has considerable fever Directed the saline mixture with occasional anodyne To continue the Lotion –

James Nugent – Seaman – Gut shot wound in the upperpart of the right thight about 2 inches from the groin – Thigh bone fractured and much Splintered – ball Supposed to be in – Several pieces of bone were extracted but the ball was not found – dressed lint Bandage with Splints – Anodyne - Rested considerably well last night but there is has been a large oozing from the wound – Applied fresh lint – no fever –

Charles Baxter – Seaman – Has lacerated wound of the left ankle – the lower part of the fibula Splintered – apparently affecting the joint. Has much Hemorrhaging from this wound – He also has a Gun Shot wound of the right thigh. The ball passed obliquely downwards through the back part of the thigh. I proposed Amputation of the left leg but he would not give his consent. Dressed both wounds with lint & Roller Bandages - Made considerable compression on the left foot in order to restrain the bleeding - has some fever this morning H Mist Salin – Tamerind water for drink – low diet.

James Kellam – O Seaman lacerated wound of the calf of the right leg – also a wound in the ham of the extremity - Dressing Simple - Today the leg somewhat Swelled and painful – slackened the bandage –

Wm. Hovington – Seaman – Complains much pain and soreness in the Small of the back and nates - It is suspected that he has received a severe contusion on the parts H Anodyne at night – N.S. ad 3xvi Apply continually Aq - Veg min to the parts –

Jas. Hall – Seaman – Has a slight wound above the eye – I suspect caused by a Splinter – Dressing Simple -

Total ascertained 12 -

Owing to the disordered state of the vessel, the wounded have wretched accommodation – if that term be used – I endeavored to make their conditions as comfortable as possible – Divided those of our people who remained on board, and were well into watches – in different parts of the vessel – Mr. Hudson, Mr. Dennison & myself sitting with the Captain - Directed Lemonade which is Tamarind water to be kept made up and served to the Wounded. End Document

Captain William Henry Allen

The Argus surrendered when the crew of HMS Pelican was about to board.14 The Pelican had suffered very little, 1 seaman was killed in the action, and 5 wounded. Her Captain John Maples RN was stuck by a muster ball, which hit a button on his coat, but was uninjured. Maples ordered the Pelican with the captured Argus to Plymouth where the wounded Americans were treated at Mill Prison Hospital. At the hospital six more men of the Argus crew men died of their wounds including Captain Allen.15 Allen had lingered for a few days following the amputation of his leg, but on 18 August 1813 succumbed to sepsis and shock.16 The British Navy in recognition of Captain Allen’s brave fight and the kindness he had shown to captured British prisoners gave him a full military funeral with 8 Royal Navy Captains as pallbearers.17 British officers were in attendance, as well as his Argus officers and some of the crew. Ira Dye in his research found as a result the battle on 14 August the USS Argus suffered “the highest per capita casualty rate of any American navy ship during the War of 1812.”18

14. James, William, Naval Occurrences in The War of 1812 ( T. Egerton, London, 1817), p. 136.

15. Dye, Ira, The Fatal Cruise of the Argus Two Captains in the War of 1812 (Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, Maryland, 1994), p. 282.

16. ADM 103/644 Account of American Prisoners of War, who Died at Mill Prison Hospital in the Week ending the 21st of August 1813.

17. Trevor, James p. 95.

18. Dye, Ira, p. 136.

The letter from the American Vice Consul John Hawker to Captain William Henry Allen’s father General Allen details the young captain’s final hours and burial with honors

John Hawker to William Allen

Plymouth 19th August 1813

Sir — The station I have had the honor to hold for many years past, of American vice consul, calls forth my poignant feelings in the communication I have to make to you of the death of your son, captain Allen, late commander of the United States’ brig of war Argus, which vessel was captured on Saturday last, in the Irish channel, after a very sharp action of three quarters of an hour, by his Britannic majesty’s ship Pelican.

Early in the action he lost his left leg, but refused to be carried below, till from loss of blood, he fainted. Messrs Edwards and Delphy, midshipmen, and four seamen, were killed; and lieutenant Watson, the carpenter, boatswain, boatswain’s mate, and seven men wounded. Captain Allen submitted to amputation, above the knee, while at sea. He was yesterday morning attended by very eminent surgical gentlemen, and removed from the Argus to the hospital, where every possible attention and assistance would have been afforded him had he survived; but which was not, from the first moment, expected, from the shattered state of his thigh! At eleven, last night, he breathed his last! He was sensible at intervals until within ten minutes of his dissolution, when he sunk Exhausted, and expired without a struggle! His lucid intervals were very cheerful; and he was satisfied and fully sensible that no advice or assistance would be wanting A detached room was prepared by the commissary and chief surgeon, and female attendants engaged, that every tenderness and respect might be experienced. The master, purser, surgeon, and one midshipman, accompanied captain Allen, who was also attended by his two servants.

I have communicated and arranged with the officers respecting the funeral, which will be in the most respectful, and at the same time economical manner. The port admiral has signified that it is the intention of his Britannic majesty’s government that it be publicly attended by officers of rank, and with military honors. The time fixed for procession is on Saturday, at eleven, A.M. A lieutenant-colonel’s guard of the royal marines is also appointed. A wainscoat coffin has been ordered; on the breast plate of which will be inscribed as below.* Mr. Delphy, one of the midshipmen, who lost both legs, and died at sea, was buried yesterday in Saint Andrew’s church yard. I have requested that captain Allen may be buried as near him, on the right (in the same vault, if practicable) as possible. I remain, respectfully, sir, your most obedient, humble servant.

(Signed) JOHN HAWKER

American vice consul

To: General Allen, &c Providence, Rhode Island.

* A tablet whereon will be recorded the name, rank, age and character of the deceased, and also of the midshipman, will be placed (if it can be contrived) as I have suggested, both having lost their lives in fighting for the honor of their country.

Source: Niles’s Weekly Register, Vol, 5, supplement (Sept. 1813-Mar.l814), p 49.

HMS Pelican v USS Argus August 1813,

from William James Naval History of Great Britain 1824The following description is by William James (1780-1827), a British lawyer by profession, before turning his hand to naval history. James wrote important histories of the naval engagements of the British with the French and Americans from 1793 through the 1820s. William James was trained in the law and began his career as an attorney. He practiced before the Supreme Court of Jamaica and served as a proctor in the Vice-Admiralty Court of Jamaica from 1801 to 1813. In 1812, when war broke out between Great Britain and the United States, James was in the United States.

James was detained by American authorities as a British subject.. After the war he went on to write his six-volume Naval History of Great Britain, 1793-1827 in reaction to American accounts of the War of 1812. His legal background influenced his approach to obtaining evidence. In search of facts, he often sought to board American warships to speak to their crews, to verify their characteristics at first hand. In this pursuit he noted, for example, that the USS Constitution was not only much larger, but also more heavily manned and armed, than HMS Guerriere – contrary to previous American claims that the ships had been equal at the time of their engagement. James was not shy to criticize British officers, as well, where he saw fit. His book reflects a search for the facts supported by documentary evidence. His account of battle between the USS Argus and HMS Pelican is not impartial but he was a stickler for facts and may have spoken with some of the Pelican's officers and crew. As Ian Toll has pointed out “James legal training is apparent thoughout the book, documentary evidence is examined with impressive thoroughness, statistics are cited authoritatively …” However, as Toll noted, James could be bitterly sarcastic.

On the 12th of August, at half past six in the morning, the British 18-gun brig-sloop Pelican, (sixteen 32-pound carronades and two sixes,) Captain John Maples, anchored in Cork from a cruise.

Before the sails were furled, Captain Maples received orders to put to sea again, in quest of an American sloop-of-war, which had been committing serious depredations in the St. George's Channel, and of which the Pelican herself had gained some information on the preceding day.

At eight o'clock the Pelican, having supplied herself with some necessary stores, got under way, and beat out of the harbour against a very strong breeze and heavy sea; proof of the earnestness of her officers and crew.

On the 13th, at half past seven in the evening, when standing to the eastward with the wind at the north-west, the Pelican observed a fire ahead, and a brig standing to the south-east. The latter was immediately chased under all sail, but was lost sight of in the night.On the 12th of August, at half past six in the morning, the British 18-gun brig-sloop Pelican, (sixteen 32-pound carronades and two sixes) Captain John Maples, anchored in Cork from a cruise.

Before the sails were furled, Captain Maples received orders to put to sea again, in quest of an American sloop-of-war, which had been committing serious depredations in the St. George's Channel, and of which the Pelican herself had gained some information on the preceding day.

At eight o'clock the Pelican, having supplied herself with some necessary stores, got under way, and beat out of the harbour against a very strong breeze and heavy sea; proof of the earnestness of her officers and crew.On the 13th, at half past seven in the evening, when standing to the eastward with the wind at the north-west, the Pelican observed a fire ahead, and a brig standing to the south-east. The latter was immediately chased under all sail, but was lost sight of in the night.

On the 14th, at three quarters past four, latitude 52°15' north, longitude 5°50' west, the same brig was seen in the north-east, separating from a ship which she had just set on fire, and steering towards several merchantmen in the south-east.

This active cruiser was the United States' 16 -gun brig-sloop Argus, (eighteen 24-pound carronades and two long twelve's,) Master-Commandant William Allen, then standing close-hauled on the starboard-tack with the wind a moderate breeze from the southward.The Pelican was on the weather quarter of the Argus, bearing down under a press of sail to close her; nor did the latter make any attempt to escape, her commander, who had been first lieutenant of the United States in her action with the Macedonian, being confident, as it afterwards appeared, that he could take any British "22-gun" (as all the 18-gun brigs were called in America) sloop-of-war in ten minutes.

At half past four, being unable to get the weather-gage, the Argus shortened sail, to give the Pelican the opportunity of closing. At a few minutes before six, St. David's Head east, distant about five leagues, the latter hoisted her colours.

The Argus immediately did the same, and, having wore round, at six opened her larboard guns within grape-distance; receiving in return the starboard broadside of the Pelican. In about four minutes Captain Allen was severely wounded, and the main braces, main spring-stay, gaff, and trysail-mast of the Argus were shot away.At fourteen minutes past six the Pelican bore-up to pass astern of the Argus; but the latter, now commanded by lieutenant William Watson, adroitly threw all aback, and frustrated the attempt, bestowing at the same time an ineffectual raking fire. In four minutes more, having shot away her opponent's preventer-brace and main after-sails, the Pelican passed astern of and raked the Argus, and then ranged up on her starboard quarter, pouring in her fire with destructive effect.

The Argus shortly after this, having had her wheel-ropes and running rigging of every description shot away, became entirely unmanageable, and again exposed her stern to the guns of the Pelican. The latter, soon afterwards, passing the broadside of the Argus, placed herself on the latter's starboard bow.In this position the British brig, at three quarters past six, boarded the American Brig, and instantly carried her, although the master's mate of the Pelican, who led the party, received his death-wound from the Argus's fore-top just as he stepped on her gunwale. Even this did not encourage the American crew to rally; and two or three of the number that had not run below hauled down the colours.

On board the Pelican, one shot passed through the boatswain's and another through the carpenter's cabin. Her sides were filled with grape-shot and her rigging and sails much injured: her fore-mast and main top-mast were slightly wounded, and so were her royals; but no spar was seriously hurt. Two of her carronades were dismounted.Out of her 101 men (her second lieutenant among the absent) and twelve boys, the Pelican lost, besides the master's mate, William Young, slain in the moment of victory, one seaman killed, and five slightly wounded, chiefly by the American musketry and langridge; [ bags of any junk such as scrap metal, bolts, rocks, gravel, old musket balls, etc. fired to injure enemy crews.] the latter to the torture of the wounded.

Captain Maples had a narrow escape: a spent canister-shot struck, with some degree of force, one of his waistcoat buttons, and then fell on the deck.

The Argus was tolerably cut up in her hull. Both her lower masts were wounded, although not badly, and her fore-shrouds on one side were nearly all destroyed; but, like the Chesapeake, the Argus had no spar shot away. Several of her carronades were disabled. Out of her 122 men and three boys, (to appearance a remarkably fine ship's company,) the Argus had six seamen killed, her commander, two midshipmen, the carpenter, and three seamen mortally, her first lieutenant and five seamen severely, and eight others slightly wounded; total, six killed and eighteen wounded.Comparative force of combatants

Broadside-guns...No Lbs. Crew Size...tons We will set the Americans a good example by freely admitting, that there was here a slight superiority against them; but then the Pelican, after she had captured the Argus, was in a condition to engage and make prize of another American brig just like her. The slight loss incurred on one side in this action is worth attending to, not only by the boasters in the United States, but by the croakers in Great Britain.

Dispatching his prize, with half her crew, including the wounded, and a full third of his own, in charge of the Pelican's first and only lieutenant, Thomas Welsh, to Plymouth, Captain Maples himself, with the Pelican and the remaining half of the prisoners, proceeded to Cork, to report his proceedings to Admiral Thornborough. On the 17th the Argus arrived in Portsmouth; and soon afterwards Captain Maples was most deservedly posted, for the promptitude, skill, and gallantry which he had displayed.Captain Allen, of the Argus, had his left thigh amputated by his own surgeon, and, notwithstanding every attention, died on the 18th August, at Mill-Prison hospital. On the 21st he was buried with high military honors, and attended to his grave by all the navy, marine and army officers in the port.

Sources:

Toll, Ian W., Six Frigates The Epic History of the Foundation of the U.S. Navy (W. W. Norton, New York, 2006), p. 461.

James, William, Naval History of Great Britain from the Declaration of War by France in February 1793 to the Accession of George IV (Baldwin, Craddock and Joy, London, 1824) Volume V pp.399-405, https://books.google.com/books?id=WWYUAAAAQAAJ&pg=PA399&dq=At+eight+o%27clock+the+Pelican,+having+supplied +herself+with+some+necessary+stores,&hl=en&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwi0jYKcntL8AhWMATQIHY- rCY0Q6AF6BAgLEAI#v=onepage&q=At%20eight%20o'clock%20the%20Pelican%2C%20having%20supplied%20herself%20with %20some%20necessary%20stores%2C&f=falseIMAGE

ADM 103/644, Account of American Prisoners of War, who have died at Mill Prison Hospital in the Week of 21 August 1812

IMAGE

USS Argus payroll for 1814On 8 September the surviving Argus men plus 170 other new prisoners were marched up to Dartmoor.19

19. Dye, Ira, p. 291.

Descriptions HM Dartmoor Prison 1812-1815

The majority of American seamen "were literate and able to express their thoughts and write about their experiences with a high degree of accuracy and articulation."20 In fact, the literacy rate may have been as high as 75 percent by the late eighteenth century and increased thereafter.21 Among the seaman confined to Dartmoor were some like Privateer Benjamin Franklin Palmer, who read books and novels and kept a diary.22 The bulk of the large prison population though read occasional newspapers and broadside for updates on the home front and the status of the war.23

20. James, Trevor, Prisoners of War At Dartmoor, American and French Soldiers and Sailors in an English Prison During the Napoleonic Wars and the War of 1812, (McParland & Company, London, 2013), p. 158.

21. Gilje, Paul A., To Swear Like a Sailor: Martime Culture in America, 1750 -1850 (Cambridge University Press, New York, 2016), p. 183.

22. Palmer, Benjamin Franklin, pp. 53, 106, 109, 135 and 142.

23. Guyatt, p. 198.

"Few groups in our history are seen through such a romantic haze as are American seafarers of the early 1800’s"24

24. Dye, Ira, "Early American Merchant Seafarers." Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, vol. 120, no. 5, 1976, pp. 331-60.

George Little, Dartmoor Prisoner number 1367 was on the privateer Paul Jones when on 23 May 1813 she was captured by HMS Leonidas. Seaman George Little, was 25 years of age, born in Massachusetts and stood 5’6½‘’ in height, an experienced seafarer and was described in the Dartmoor entry book as "stout" (strong).

American Privateer Paul Jones Captured by HMS Leonidas 1813

Naval History and Heritage CommandGeorge Little’s narrative of his life both as sailor and prisoner during the War of 1812 is one of the best, especially his account of first viewing Dartmoor after a nine day march from the depot at Stapleton.

"A more miserable and wretched spot…"

This most fatiguing and harassing march was continued for nine days, during which many of the prisoners broke down, and were so entirely disabled that it became necessary to transport them in wagons. So unremitting was the vigilance kept over us (during the remainder of the march—after my project of escape had failed—that every effort to get away on the part of the prisoners proved ineffectual. At length, however, we arrived at Dartmoor; and I think I shall not overstep the bounds of truth, when I say, that a more miserable and wretched spot could not have been selected in the island of Great Britain, to erect a depot for prisoners of war, than this same barren heath presented. In vain may the eye exert its powers of vision to seek for shrub or verdure, and in vain may the mind contemplate a scene more melancholy than to see six thousand intelligent beings, confined in a circumference of about one half of a mile, strongly fortified, and encircled by walls, ditches and palisades, with cannon so planted as to command every part of the enclosure. It was nevertheless a relief to enter even this place, bad as it was, where we, might find rest for our wearied limbs and debilitated bodies. But if the location of Dartmoor inspires the mind with gloom at first sight, much more sensibly did I feel the horrors of confinement, when thrust into the interior. There were about six thousand American prisoners, who had been gathered from all the prisons and prison-ships in England.

Benjamin F. Palmer, Dartmoor Prisoner number 3944 was a seaman of the privateer Rolla who was captured on 10 December 1813 remembered the intake process thus:

October 5th 1814,

New entries to Dartmoor were mustered from a list of names and they give each one a hammock and bedding and we entered into the old prison kept for reception of prisoners. Our baggage soon arrived and everyone gets his things and away to bunk. We have some bread served out which is very acceptable, we sleep but very little being almost froze the prison being all open and our bone aching.

October 6th 1814

This morning the Clerk and Turnkeys came and measured us and one by one took down our completion, scars, place of birth, etc.25

25. Palmer, Benjamin Franklin, The Diary of Benjamin F. Palmer, Privateersman: While a Prisoner on Board English War ships at Sea, in the Prison at Melville Island and at Dartmoor (The Acorn Club, Connecticut,1914), pp. 102-103.

Charles Andrews, Dartmoor Prisoner number 381, also number 678, was a seaman on the privateer Virginia Planter which was captured off Nantes, France, on 18 March 1813, recollected his entry in Dartmoor Prison and the historic cold winter of 1814 thus:

Thus we marched surrounded by a strong guard through heavy rain over a bad road, with only our usual scanty allowance of bread and fish. We were allowed only once to stop during the march of seventeen miles. We arrived at Dartmoor later on the after part of the day and found the ground covered with snow. Nothing could form a drearier prospect than that which now presented itself to our hopeless vision. Death itself seemed less terrible than this gloomy prison.

Charles Andrews Diary also provides one of the best accounts of the historic winter of 1814. That year the mean temperatures for the month of January were 26.8 a month so cold that the Thames River froze. He also noted eight prisoners who used the snow to plot a dramatic but ultimately foiled escape.

The year commences with as cold weather as we have ever experienced in the city of New York; the buckets in the prison, in the space of four hours froze. The prisoners must invariably have frozen were not the hammocks placed so near together to communicate the animal heat from one man to another. The running stream that supplied the prison froze solid and the weather was allowed to be colder than it had been for fifty years before. On the 1st the snow was two feet on the level and it began to snow again, it snowed the greater part of the time until the ninetieth…drifts in the year were as high as the prison walls (nineteen feet).

At midnight this dreary night eight prisoners thinking to take advantage of the night to make their escape as no sentries were in sight formed a ladder and ascended and descended the first wall directly against the guard house and in descending the second the soldiers in the guard house discovered them and apprehended seven; the eighth no quite over the wall made his escape…. These seven were taken to the guard house and there put into the black hole which is the place for prisoners who attempt to make their escape the weather being extremely cold it was likely to prove their last. But the fifth day they were removed to the cachot and remained on two thirds allowance for ten days; sleeping on straw.2626. Andrews, Charles, A Prisoners Memoirs of Dartmoor Prison (Printed for the author, New York, 1815), pp. 10, 34-35.

Benjamin Brown, Dartmoor Prisoner number 3598, a 21 year old clerk on the privateer Frolic arrived in Dartmoor on 30 September 1814. The Frolic was captured in the West Indies on 25 January 1814 so Brown and his shipmates had to endure a long Atlantic crossing to Portsmouth, England, where they were placed on board the HMS Sybille and transported to Plymouth. At Plymouth the captives were placed in an unnamed hulk, where the next morning they were mustered by name and placed under armed guard for the 19 mile march to Dartmoor Prison. Toward evening, after a cold and arduous march, Brown and his fellow seafarers entered into Dartmoor Prison. For their first night, the entrants were confined to a cold damp and dirty room. Brown was a keen observer, taking an anthropologist's interest in his surrounding and environment. Here, he describes the weather. Like many prisoners, Benjamin Brown found Dartmoor had some the worst weather on the Devon coast in terms of wind, rain and cold. As a consequence, prisoners confined to stone cells with open windows for long periods, suffered and died at high rates from respiratory diseases such as tuberculosis and influenza.

The situation of the prisons was a very unhealthy one, and great mortality generally prevailed among the prisoners. Situated as it was on a mountain said to be seventeen hundred feet above the level of the sea, in a climate proverbial as is the west of England for moisture of atmosphere, poorly paid and scarcely clad, immured in gloomy stone prisons, which a ray of sun scarcely ever penetrated, without glass in the windows to guard us against the cold and dampness, and no fires allowed in the prisons, we could not otherwise be unhealthy. The weather when except by mere chance it was fair was continually drizzling.

The official scale of rations for Dartmoor prisoners of war yielded approximately 2,400 calories per day. This was barely enough to sustain fit and healthy men let alone prisoners confined to overcrowded rooms and exposed to cold and disease. Brown also provided a description of the prisoner’s rations and diet:

Our allowance was a half-pound of beef per man which was delivered in the gross was diminished considerably in weight by cooking and the abstraction of the bone; some turnips or onion, a little barley and one third ounce of salt. On Wednesdays and Fridays in lieu of beef, we had smoked or pickled herring and one pound of potatoes or in lieu of herrings we had one pound pickled codfish. We had one pound of bread for each man which was generally of good quality. We had no allowance for breakfast or supper – but to remedy this deficiency we were paid by our government two pence half penny per day to us every thirty days, amounting to six shillings and eight pence or about one and half dollars.27

27. Brown, Benjamin Frederick, editor, Nathaniel Hawthorne, The Yarn of a Yankee Privateer, (Funk and Wagnalls Company, New York, 1926), pp. 422. First published as Papers of Old Dartmoor, U.S. Democratic Review, New York, in seven parts, January to September 1846.

27a. James, Trevor, p. 59.

Perez Drinkwater, Dartmoor Prisoner number 937 was a lieutenant aboard the privateer Lucy, which was captured by the HMS Billerkin on 13 January 1813. The entry record for Drinkwater stated he was 25 years of age, 5’ 9" tall and described as "long haired". Letters from American prisoners in Dartmoor are rare, for as Drinkwater wrote, "I am compelled to smuggle this out of prison for they will not allow us to write to our friends, if they can help it". We are indeed fortunate to have the few Drinkwater was able to get past the guards.28

28. Felknor, Bruce, "A Privateersman's Letters Home from Prison" http://www.usmm.org/felknor.html

Dear Sally –

Royal Prison Dartmoor, Oct 12, 1814

It is with regret that I have to inform you of my unhappy situation,, that is, confined here in a loathsome prison where I have worn out almost 9 months of my Days; and god knows how long it will be before I shall get my Liberty again. . . . I cheer my drooping spirits by thinking of the happy Day when we shall have the pleasure of seeing you and my friends. . .

This same place is one of the most retched in this habited world . . . neither wind nor water tight, it is situated on the top of a high hill and is so high that it either rains, hails or snows almost the year round for further particulars of my present unhappy situation, of my strong house, and my creeping friends which are without number. . . .

. . . my best wishes are that when these few lines come to you they will find you, the little Girl [his daughter] my parents Brothers sisters all in good health I have wrote you a number of letters since my imprisonment here and I shall still trouble you with them every opportunity that affords me till I have the pleasure of receiving one from you which I hope will be soon. . . .

I am compelled to smuggle this out of prison for they will not allow us to write to our friends if they can help it. . . . So I must conclude with telling you that I am not alone for there are almost 5,000 of us here, and creepers a 1000 to one. . .

Give my Brothers my advice that is to beware of coming to this wretched place for no tongue can tell what the sufferings is here till they have a trial of it. So I must conclude with wishing you all well, so God bless you all. This is from your even [ever] dear and beloved Husband.

Josiah Cobb, Dartmoor Prisoner number 6632, a 19 year old seaman was captured in the privateer Prince de Neufchatel on 28 December 1814and was entered into Dartmoor Prison on 30 January 1815. Cobb was released on 5 July 1815

The next morning they were turned out into the yard, where we found a number of prison officials waiting for us. Each man was measured, and his height recorded in a book, he was critically examined and his face peered into to discover any marks by which he could be distinguished; this and complexion were likewise recorded. He was interrogated as to his age, place of nativity, the vessel he was captured in, and the station he filled on board. His answers were set down against his name. After we had been measured and interrogated each man received a hammock, bed, blanket, pillow, a bunch of rope yarn, a tin pot with a wooden spoon and to every sixth man a three gallon bucket.29

29. Brown, Benjamin Frederick, editor Nathaniel Hawthorne, The Yarn of a Yankee Privateer, Funk and Wagnalls Company, New York, 1926), pp. 161-167. First published as Papers of Old Dartmoor, U.S. Democratic Review, New York, in seven parts, January to September 1846.

As soon as dismounted from the wagon, the five of us were ushered into the clerk’s office, to have our names recorded and numbered according to seniority of entrance and ages, heights, and birth places noted down opposite our names. My number was 6632 which shows how many prisoners had preceded me to this dismal abode I was about entering, after having gone through with registering, a hammock and blanket were given to each "to be returned when released"…

The turnkey opened the portal in which we entered, and the ponderous door of bars and rivets was slammed in our rear… I stood, collected my sight and senses from the glare of the light and hum of many voices which burst upon me, the only conclusion I came to was that I had suddenly awakened from a disturbed dream which left me where I was, in reality in Pandemonium.30

30. Cobb, Josiah, A Green Hands First Cruise roughed out from the log book of memory of twenty five years standing Together with a residence of five months at Dartmoor Prison. By a Yonker (Baltimore, Cushing and Brother, 1841), pp. 1-6.

The General Entry Books of American Prisoners of War at Dartmoor Prison & What They Reveal

"The detailed personal information on these men recorded in the General Entry Books is the richest single source of data relating to early American seafarers"31 These prison records provide each prisoner’s number, name, ship, date and place of capture, rank, birthplace, age, physical description and details of discharge, death, or escape. Each of these follow a standard form which contained details of which ship captured the named prisoners, from which vessel, and when.

31. Dye, Ira.

General Entry Book of American Prisoners of War

at Dartmoor Prison, entry 1090 William BriggsTypes of Personal Information Collected

The personal information collected in the General Entry Book of American Prisoners of War at Dartmoor Prison is a treasure trove of data for historians and demographers. Prior to the invention of photography, this collection process insured every inmate had a "word picture" entered on record, see above.31 On entrance to Dartmoor Prison, all prisoners were assigned a prison number, then examined by the clerk who carefully recorded information regarding their background, physical characteristics, etc. For example: in the column nativity or place of birth, a review of these records reveal most of the American seafarers imprisoned in Dartmoor were native to either Boston, New York or Philadelphia. In the column "Stature", we get our best evidence regarding the average height of American seafarers. Based on the data collected by Ira Dye, the average height of crew of the U.S.S Argus was 5’5" in height.32 Dye found the mean height of 5,317 men 21 years or older in the Dartmoor prison sample was 66.85 inches or 5.57 feet.33 Scholar Simon P. Newman found a similar distribution of height in his study of Philadelphia seafarers 1798-1816, with a mean height of 66.4 inches. He also noted these "white mariners were, on average, a striking 1.7 inches shorter than white male recruits in the Continental army"34 Newman concludes such data demonstrated compelling evidence of the ubiquity of multigenerational poverty and poor nutrition.35

31. James, Trevor, p. 114.

32. Dye, Ira, The Fatal Crew of the Argus Two Captains in the War of 1812 (Naval Institute Press, Annapolis Maryland, 1994), p. 136.

33. Dye Ira, "The Height of Early American Seafarers 1812-1815," The Biological Standard of Living on Three Continents: Further Explorations in Anthropometric History, John Komlos editor ( Routledge, New York, 1995), p. 97.

34. Newman, Simon P. "Reading the Bodies of Early American Seafarers." The William and Mary Quarterly, vol. 55, no. 1, 1998, pp. 59-82, see page 65.

35. Newman p. 110.

For Those in Peril on the Sea

Even in peacetime, seafaring was and is one of the most dangerous occupations in the world. In the entry book column labeled "Marks", we find descriptions of prisoner’s scars and amputations, with the most common injuries to the extremities broken or missing fingers and injuries to legs feet and toes were commonplace.36 In this column we also find descriptions of birthmarks, knife and gunshot wounds, genetic defects such as moles and freckles. To this list the examiners entered marks left by diseas, such as small pox. Small pox (variola virus) was definitely the most common notation in this category.

36. Newman, p. 111.

President James Madison on 27 February 1813 signed the first major piece of vaccine legislation to combat smallpox, entitled "An Act to Encourage Vaccination", but the implementation was at best haphazard. During the War of 1812, the U.S. War Department ordered vaccination to prevent smallpox; the US Navy did the same. At Dartmoor growing concern about a possible outbreak of small pox led Royal Navy Surgeon Dr. George Magrath to begin a smallpox vaccination program in January 1815, but this was also too late as the virus had killed numerous prisoners.37

37. Guyatt, p. 246.

In column "Visage & Complexion", white sailors were described by facial characteristics "long" "oval" and "round face". Black sailors were listed as "Black", "Negro", and occasionally as Seaman John Berryman of Maryland, was a "Man of Colour". In all the General Entry Book of American Prisoners of War, Dartmoor U.K., 1813-1815, recorded names of 6,550 seamen, 955 of those prisoners were described as Black, 14 of which gave their place of birth as Africa.38

38. Dartmoor General Entry Books for American Prisoners of War, ADM 103/87, 88, 89, 90, and 91, British National Archives.

Privateers

During the War of 1812, both the British and the American governments used privateers. Prize money served as an important incentive encouraging men to serve at sea. This was true for the regular navy, and was even more significant for the men who signed aboard the more than 500 authorized privateers, sponsoring privately owned ships and commissioned by the government to capture enemy commerce in a form of legalized piracy.39

39. Gilje, Paul A., "Cruising for dollars: Privateers in the world of 1812" NPS Series: "The Luxuriant Shoots of Our Tree of Liberty:" American Maritime Experience in the War of 1812, National Park Service, https://www.nps.gov/articles/cruising-for-dollars.htm

The U.S. Congress declared that war be and the same is hereby declared to exist between the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and the dependencies thereof, and the United States of America and their Territories; and that the President of the United States is hereby authorized to use the whole land and naval force of the United States to carry the same into effect, and to issue to private armed vessels of the United States commissions of marque and general reprisal, in such forms as he shall think proper, and under the seal of the United States, against the vessels, goods and effects of the Government of the said United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, and the subjects thereof.

During the war, over 200 American privateering vessels were captured by the Royal Navy, and their officers and crews incarcerated at Dartmoor and other royal prisons. Despite these losses, privateers were essential to the American war effort, for they collectively captured and sunk as many as 2,500 British ships and which has been estimated as approximately $40 million worth of damage to the British economy.40

40. Tabarrok, Alexander (Winter 2007). "The Rise, Fall and Rise Again of Privateers" (PDF) The Independent Review. Vol. XI, no. 3., pp. 565-577, https://www.independent.org/pdf/tir/tir_11_04_06_tabarrok.pdf

Confinement and Escape

Dartmoor Prison, unlike many early nineteenth century English detention facilities, was purposely built in a remote isolated location, ringed by high stone walls and manned by hundreds of armed militia sentries. In addition, a rope ran around the entire circumference of the prison which was linked to a series of bells that quickly spread an alarm. Even if a determined prisoner made it beyond the prison walls, he would still have to traverse ten miles on foot over wild moorland and bogs, an area frequently beset with fog and chilling winds to reach the nearest town.41 Local residents turning in an escapee could expect a reward of a guinea.42 The typical punishment after a failed breakout was solitary confinement in a cachot (black hole) and reduced rations.43 Yet, despite these daunting odds, scholar Nicholas Guyatt has tallied a total of twenty-four American prisoners of war successfully made their way to freedom.44

41. Guyatt, Nicholas The Hated Cage: An American Tragedy in Britain's Most Terrifying Prison (Basic Books, New York, 2022), p. 204.

42. James, Trevor, p. 75.

43. Guyatt, p. 205, and see James, pp. 53-53.

44. Guyatt, p. 208.

Dartmoor quickly acquired a formidable reputation as a terrifying prison. In June 1814, a group American prisoners of war confined in the prison ship HMS Nassau, after learning of their scheduled transfer to Dartmoor, drew their knives on sentries, then seized the jolly boat and pulled for the nearest shore. The group was quickly overtaken by Royal Marines from the HMS Nassau and other ship boats. During the capture three prisoners were wounded but all four returned to the ship.45

45. The Observer (London, Greater London, England), 26 June 1814, p. 3.

Dartmoor prisoner number 22, John Newell, a cook, on the privateer Tiger, was born in Africa. In the Dartmoor entry book he was listed as "Negro", and 37 years old, 5'4'' in height, "stout" (strong). Newell and the crew of the Tiger were captured on 8 Aug 1813. Newell was finally released 16 Mar 1815. He was the first black seaman captured in 1812 but by war's end there would be over 900 black men in Dartmoor.

HM Gibraltar prisoner number 48, John Newell. During the War of 1812, Great Britain used prisons throughout its vast empire in locations scattered around the world to temporarily incarcerate Americans. These prisons were located in the Bahamas, in Canada at Halifax, Nova Scotia and Quebec. Britain also maintained prison facilities on the island of Malta and another at Gibraltar, Spain. The attached entry confirmed that on 5 August 1813 John Newell and the crew of the Privateer Tiger were capturedby HMS Andromeda and subsequently delivered to HM Prison at Gibraltar. There Newell and his shipmates were kept locked up until they could be safely transported to England. Privateer John Newell is prisoner number 48, in the attached General Entry Book of American Prisoners of War at Gibraltar.

Richard Crafus, Dartmoor prisoner number 6303. Richard Crafus, aka "Richard Seavers", was a black seaman, who was born in Vienna, Maryland, about 1791. In 1814 he was working as a sailor aboard the privateer Requin when that vessel was captured by the HMS Venus off Bordeaux, France, in the river Garonne, on 6 March 1814.46 Credit for the capture of the Requin officially was assigned to the army of General Lord Arthur Wellesley, later Duke of Wellington.

46. "Capture of the Ship Requin in the Garonne by Mr. Ogilvie" Hansard House of Common’s Debates, 02 July 1823 , volume 9, cc1405-12.

Richard CrafusRichard Crafus had refused enlistment in the Royal Navy and first was imprisoned in the hulks at Chatham before being sent on to Dartmoor.47 His Dartmoor entry #6303 described him as 6’3¼", stout (strong) with a round face, black complexion, black hair and black eyes.48, 49 Standing well over six feet tall and a trained boxer, he literally towered above his contemporaries. In the writing of former prisoners, it is apparent Crafus was an object of both awe and fear. He quickly became the leader of Dartmoor’s black inmates after the white American prisoners successfully petitioned the British prison administration for segregation.50 A recent examination the General Entry Books of American Prisoners of War at Dartmoor by scholar Nicholas Guyatt, found "Eight Hundred and Twenty - Nine Sailors of Color had been entered into the register by the end of October 1814."51

47. Fisher, David Hackett, American Founders: How Enslaved People Expanded American Ideals (Simon & Schuster, New York, 2022), p. 671.

48. Lipke, Alan Thomas, "The Strange Life And Stranger Afterlife Of King Dick including His Adventures in Haiti and Hollywood With Observations On The Construction Of Race, Class, Nationality, Gender, Slang Etymology And Religion" (2013,. Graduate Theses and Dissertations http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/453

49. Jones-Minsinger, Elizabeth, “Our Rights Are Getting More & More Infringed Upon”: American Nationalism, Identity, and Sailors’ Justice in British Prisons during the War of 1812.” Journal of the Early Republic, vol. 37, no. 3, 2017, pp. 471–505, see p. 490.

50. Guyatt, pp. 180-184.

51. Guyatt, p. 219.

After the prison division, Crafus became known as “King Dick”, the leader of Prison Number Four. According to memoirs written by white inmates, he ruled strictly and fairly. This meant that life in Prison Number Four was perceived as more desirable than elsewhere in Dartmoor Prison. Because King Dick allowed whites to transfer to Number Four, many whites did so. In 1815, the British released the American prisoners of war.

Following the peace, Richard Crafus went to Boston where he taught boxing from 1826 through 1835. He also served as an auxiliary in the police department. "He led an annual procession around Boston Common on Election Day, after which he gave a patriotic speech." He died on 12 February 1831 in Boston “of a severe cold induced by exposure” possibly influenza.5252. The Liberator, (Boston, Massachusetts), 12 February 1831, p. 27.

Escape from Dartmoor Prison

General Entry Book of American Prisoners of War at Dartmoor, Admiralty Records (ADM) no 929,

James McFaddenJames McFadden, Dartmoor prisoner number 929 became the first American to escape Dartmoor Prison. McFadden was born in New York, was recorded as age 26 and 5’11½". At the beginning of the war, McFadden was 2nd mate aboard the privateer Brig General Armstrong. The vessel was armed with seven guns including a 42-pounder Long Tom cannon and had a crew of 90 men. The General Armstrong turned into a highly successful privateer and captured multiple ships. One of these was the British ship Fanny from Pernambuco bound to Liverpool, with a valuable cargo of cotton, coffee and tallow, etc. The General Armstrong engaged the Fanny forty minutes before she struck her colors; the Fanny had six men severely wounded and one killed, her hull rigging and sails were considerably cut up, but the Armstrong received no damage.

53. “The Privateer Brig General Armstrong, Captain S. C. Reid Commander, which fought a thrilling battle in the Harbor of Fayal" The artist unknown, date unknown, image from George Coggeshall, History of the American Privateers, and Letters-of-marque, During Our War with England in the Years 1812, 1813 and 1814, (G P Putnam, New York, 1861), p. 273.

McFadden was named prize master (acting captain) with instructions to take her to a safe port or harbor. Unfortunately, HMS Sceptre recaptured Fanny on 12 May and returned, arriving off Skelling Rock on the west coast of Ireland on 8 June. A Russian man-of-war ran afoul of Fanny in the Downs on 18 June, causing the Fanny to lose a mast and suffer other damage. She arrived in Gravesend on 24 June. She finally arrived in Liverpool on 26 September. McFadden and the crew were transferred to HM Dartmoor.

In September of 1814, British boarding parties from nearby royal ships attacked the General Armstrong while she lay in a neutral port in the Azores. Ultimately, the privateer was abandoned by her crew, but the British had suffered close to 200 casualties compared to only nine for the United States. "The Americans," said an English observer, "fought with great firmness, but more like bloodthirsty savages than anything else, British officials were so embarrassed by their losses in this engagement that they refused to allow any mail on the vessels that carried their wounded back to England, see Hickey, p. 219.

Escape of American Prisoners of War on the road to Dartmoor

London, June 30, 1814American prisoners of war under escort to Dartmoor were on occasion lightly guarded and, as in this case, were able to break free of their confinement while lightly guarded. Taunton is about sixty miles from HM Dartmoor Prison. The prisoners were housed in the Old Angel Inn (probably in a barn) which was located in the middle of the town of Taunton, on main road to the West of England and Dartmoor.

Saturday a detachment of American prisoners arrived at Taunton on their route to the depot at Dartmoor. In the middle of the night they contrived, by taking up the flooring of the room in which they were confined at the Old Angel Inn, and digging down to admit their escape. Twenty-seven succeeded in getting out, of whom eleven only have been retaken.54

54. New England Palladium, 9 September 1814 (Boston, Massachusetts), p. 3.

John Wilson, Dartmoor Prisoner number 1729. Wilson escaped while on the arduous 17 miles uphill march from HM Plymouth Prison to HM Dartmoor Prison. He and the other American prisoner were just off ship and had not marched for a while.55 Many of the men were shoeless and poorly clothed as they tread the stony path. Wilson had been captured on the privateer Governor Garry while serving as a seaman on 31 May 1813. He is described as 20 years of age and born in Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania.

55. Bolster, W. Jeffrey, Black Jacks: African American Seamen in the Age of Sail (Harvard University Press, Cambridge Massachusetts, 1997), p. 104.

General Entry Book of American Prisoners of War at Dartmoor, Admiralty Records (ADM) no 6523

Caleb RichmondCaleb Richmond, Dartmoor Prisoner number 6523. Caleb Richmond a 34-year old black seafarer was born in Pennsylvania. He was in the Royal Navy at the outbreak of the War of 1812 but voluntarily gave himself up as not willing to fight his own country. Richmond was first placed in the Chatham hulk HMS Ganges and subsequently transferred to Dartmoor Prison. On 1 June 1815 Richmond became the first black prisoner to escape Dartmoor Prison.

John Langford, Dartmoor Prisoner number 774, the Great Escapist.

On 26 October 1813, John Langford, an experienced sailor, age 25, standing 5’5’’ and born in Somerset New Jersey, had taken a position aboard the privateer Betsy which was captured by HMS Eurotas off the island of Ushant near the Southwestern end of the English Channel.56 The Eurotas, launched in 1813, was a 35-gun British frigate. After capture, Langford and the rest of the crew were first takent HM Prison Plymouth and then on to HM Dartmoor as prisoner #774.56. General Entry Book of American Prisoners of War at Dartmoor, Admiralty Records (ADM) no. 774, British National Library.

Langford made his first try at fleeing Dartmoor Prison on the morning of 16 October 1814 and his second attempt two months later on 8 December 1814. Following each attempt Langford was placed in the prison cachot (a dungeon or black hole) for a number of days as punishment. Here in a cold, dark, confined space and on reduced rations, he plotted his next attempt.57His final and successful escape was on 3 February 1815.

57. Palmer, p. 176.

Reward Notice, for Swaine and Grasshon, Morning Chronicle (London, Greater London, England),

8 November 1814Thomas Swaine, Dartmoor Prisoner number 2971. Swaine was a 29-year old officer of the privateer Wily-Reynard, a schooner from Boston. Early in the war, the Wily-Reynard was highly successful taking three ships, two brigs and four schooners as prizes.58 The Wily Reynard had a crew of 6o men and carried 14 guns and was captured on October 11, 1812, by HMS Shannon.59Thomas Swaine escaped on 3 November 1814 with fellow prisoner Lieutenant Richard Grasshon.

58. Kert, Fae M. “Privateering Prizes and Profits: The Private War of 1812” The Routledge Handbook of the War of 1812, editors Donald R. Hickey and Connie D. Clark (Routledge, New York, 2015), p. 65.

59. McClay, Egar Stanton, A History of American Privateers (D. Appleton and Company, New York, 1899), p. 234.

Lt. Swaine has been described by one historian as "a murderous thug".60 A reward notice for him and another prisoner was quickly issued, headlined “Escape of American Prisoners of War”, with the Navy offering a Five Guinea reward.61 A memorandum copied onto Swaine’s Dartmoor Prison entry stated “this man reported by order of Sir R. Brieden on being account of murdering [August 1812] an old man [Francis Clements] in a most wanton and cruel manner on a small island a little to the Westward of Halifax N.S. called Sheep Island.”62

60. Emmons, George Foster, The Navy of the United States 1775-1853 (Gideon & Co, Washington, DC, 1853), pp. 196, 200-201.

61. Kert, Faye M. Privateering Patriots and Profits in the War of 1812 (Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, 2015), p. 104.

62. Morning Chronicle (London, Greater London, England), 8 November 1814, p. 1.

As a lieutenant of the Wiley-Reynard, Thomas Swain had overseen this shocking raid which the laws of war and his own commission strictly forbade him.63, 64 British anger was such that Lt. Swaine was the subject of a letter from Lieutenant Governor Sherbrook to Lord Bathurst excoriating his conduct and flagrant violation of law and urging his punishment. The Wiley Reynard was later captured by the 38 gun frigate HMS Shannon. Following his capture Lt Swaine was first incarcerated in the HM Melville Island Prison and subsequently moved to HM Dartmoor Prison.65

63. General Entry Book of American Prisoners of War at Dartmoor, Admiralty Records (ADM ) no. 2971.

64. Guyatt, p. 208.

65. Kert, pp. 104-105.

Two of the Youngest Prisoners

General Entry Book of American Prisoners of War at Dartmoor, Admiralty Records (ADM) Nathaniel Lee, prisoner, # 2657,

Nathaniel Lee, Dartmoor Prison number 2607. Nathaniel Lee was rated a "Boy” or young seaman in training. He was born in Marblehead, Massachusetts, and served on a privateer, the schooner Growler. The Dartmoor Entry Book recorded Lee as 12 years of age, and his height 4'2'', making him the youngest and shortest sailor.The Growler, under Captain N. Lindsey, had had a relatively successful cruise, having taken the ship Arabella, a brig, the schooner Prince of Wales, and the brig Ann. On 7 July 1813, the Growler's luck ran out when she was captured by the HMS Electra. The Electra with 18 guns overtook the Growler after a six-hour chase. In a quick short fight, the privateer Growler was no match for a Royal Navy schooner as she had only one long 24-pounder gun and four 18-pounder guns. After capture, the crew of the Growler was delivered to Chatham, England, where they were placed in (prison ship) the HMS Freya. Prison hulks like the Freya were decommissioned naval vessels that authorities used as floating prisons in the 18th and 19th centuries. Due to the large number of prisoners of war and few purpose-built prisons, converted ships or hulks, were extensively used in England to house prisoners of war. During the War of 1812, boys like Nathaniel Lee ranging in ages 12-16, often served in U.S. Navy vessels and privateers.

John Seapatch, Dartmoor Prison number 5889, was twelve years old and was rated as Boy. He was in the crew of the privateer Harlequin when she was captured by the British. Harlequin was a schooner of 232 tons, and her captain Elishu D. Brown, she had 10 guns and about 117 men. She sailed from Portsmouth, cruising, and was out only four days when she was captured October 23, 1814, by HMS Bulwark, a 50-gun ship of the line. John Seapatch was born in Massachusetts and according to Dartmoor prison records was 4 feet, 8 inches tall with grey eyes and a fair complexion. Seapatch was supplied with bedding at the prison in December 1814 and barely two months later died on 7 February 1815 of Tabes Mesenterica a form of tuberculosis.

An Old Salt and a Black Patriot

John Kelley, Dartmoor Prison number 3756, a seaman of Marblehead, Massachusetts, was 62 years of age and part of the crew of the privateer Alfred when she was captured by the sloop HMS Epervier, Commander Richard Walter Wales, on 23 February 1814 off the coast of Newfoundland. The brig Alfred, mounted 16 long 9-pounder cannon but surrendered without a fight. John Kelley and his shipmates were later transferred to Halifax, Nova Scotia, and subsequently taken to HM Dartmoor Prison. Kelly died of anascara condition in which kidneys no longer function and the body retains too much fluid.

Engraving of Henry Van Meter,

Harper’s Magazine October 1864Henry Van Meter, Dartmoor Prison number 5859. Henry Van Meter was born into slavery approximately 1766. His enslaver was General Thomas Nelson, governor of Virginia. Henry Van Meter fought at the Battle of Fallen Timbers in 1794 with General Anthony Wayne. He escaped his enslavers and in his forties, with the help of some Philadelphia Quakers, taught himself to read and write. “At some point between 1805 and 1814, when he was anywhere between forty and fifty years of age, Henry Van Meter decided the next chapter of his extraordinary life would take place on the ocean.66

66. Guyatt, pp. 22-23.

During the War of 1812, he volunteered and sailed aboard the Baltimore privateer Lawrence as a seaman. The Lawrence, a Baltimore schooner, was both fast and nimble and one of the wars most successful American privateers. She was armed with one long gun and 12 eighteen pound cannonades. During the course of the war, her crew of 120 officers and men captured twenty-two British merchant vessels. Her numerous prizes, both vessels and their cargos, were sold at Baltimore and made her investors and officers a very hefty return. For crewman, such as Van Meter, they were paid agreed upon shares of the booty. One of the Lawrence prizes, the Portland brig Lion upon capture off Lisbon, Portugal, was crewed by a small detachment of Lawrence sailors. As the Lion was sailing for Baltimore, she was overtaken the 38 gun frigate, HMS Granicus and faced with overwhelming firepower quickly surrendered. After the capture of the Lion, Henry Van Meter and the rest of her small crew were transferred as prisoners of war to HM Dartmoor Prison. There he remained incarcerated and witnessed the infamous Dartmoor Massacre. He was finally released on 2 July 1815.

Henry Van Meter died on February 14, 1871, and is buried in Mt Hope Cemetery, Bangor, Maine. The clerk recorded Henry Van Meter’s name into the General Entry Book of American Prisoners of War at Dartmoor Prison, in a somewhat muddled script which was later input into Ira Dye’s Dartmoor “Prisoner of War Data Base” as, “Vaumetro, Henry”, https://ussconstitutionmuseum.org/ira-dye-prisoner-of-war-database/

Henry Van Meter is described, upon his entry into the prison, as being 39 years of age. He was also listed as stout [strong], 5’ 10¼" tall, complexion, Black, with scar on his left hand. The same page enumerated two other Black sailors captured on the Lion, they were number 5856, Robert Beaton,and number 5861, Henry Watson.

Source: John Philips Cranwell and William Bowers Crane, Men of Marque (W.W Norton & Company, New York, 1940), 371-401.

Tattoos

General Entry Book of American Prisoners of War at Portsmouth

In the early Navy and merchant marine, tattoos were inked on ship. There is also evidence for American prisoners receiving tattoos at Dartmoor.67 On a man-of-war it is called tattooing or pricking. Novelist Herman Melville who served aboard whaling vessels and the frigate USS United States recounts the practice of “pricking” or tattooing aboard that vessel in 1844.

67. Gilje, Paul A., p. 261.

Some tattooists, or prickers, were celebrated in their way as consummate masters of the art. Each had a small boxful of tools and coloring matter; and they charged so high for their services that at the end of the cruise they were supposed to have cleared upward of four hundred dollars. They would prick you to order: a palm-tree, or an anchor, a crucifix, a lady, a lion, an eagle, or anything else you might want.”68

68. Melville, Herman "White Jacket or the World in a Man-of-War G", editor Thomas Tansselle (Library of America: New York 1983), p. 525.

Scholar Ira Dye summarized his findings: that the majority in the HM Dartmoor Prison Entry Books and Seaman Protection Certificate's descriptions of tattoos were of the sailor’s initials or his loved ones. Next in popularity were nautical symbols, e.g. anchors, ships and the seven stars. Ira Dye found about 6% of U.S. seamen were tattooed during the War of 1812. The first page of General Entry Book of American Prisoners of War Portsmouth (see above) entry numbers 1-10 has three sailors as “marked”, aka tattooed. They are:

No.1 Joshua Paine, “mark of a coconut tree, right arm”

No. 6 Peter Evan, “B. R. marked on left arm”

No. 9 Celeb Daymen, “marked with 7 Stars, left arm”

Caleb Daymen’s tattoo represented the seven stars composed of Rigel, Betelguese, Bellatrix, Mintaka, Alnilam, Alnitak and Sapih. The seven stars were in use before the advent of the Global Navigation Satellite System (GNSS) when seafarers looked to find Orion as a navigation aid. These are some of the brightest stars in the night sky, and were and are used to assist a sailor locating Orion to fix a positon and return home safely.

Samuel Wessel, Dartmoor Prisoner number 340. Seaman Samuel Wessel’s, entry notes include he was seaman, age 20. In the column “Marks” the Dartmoor clerk wrote "His Mothers Mark, Left Arm". In 1813 the word “tattoo” was not commonly used.69

69. Dye, Ira " Seafarers: A Profile, 1812, Prologue" Journal of National Archives and Records Administration, 5 (Spring 1973):

10. 4.A Black Hero of the War of 1812

Jesse Williams, Dartmoor Prisoner number 3319. Jesse Williams was born in Pennsylvania in 1772 and enlisted on the USS Constitution in August 1812. Williams saw action aboard the USS Constitution during her historic victories against HMS Guerriere and HMS Java. Eventually, in 1813 he was transferred to the Great Lakes to serve under Commodore Oliver Hazard Perry. At the Battle of Lake Erie, Williams served on the USS Brig Lawrence and later the schooner USS Scorpion and was wounded during the battle. Williams was captured and taken to HM Dartmoor Prison and was finally released 3 July 1815. For his heroic service against the British squadron at Put-In-Bay, he was awarded $214.89 in prize money and eventually in 1820 a silver medal from the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania.

z

Seaman Jesse Williams, War of 1812 pension and detail of the payroll USS Constitution

April 1813 listing WilliamsThe Dartmoor Massacre 6 April 1815