American Seamen’s Protection Certificates & Impressment

1796-1822By John G. M. Sharp

At USGenWeb Archives

Copyright All right reservedIntroduction: Seamen’s Protection Certificates were also known as "Seamen Certificates,” "Sailor's Protection Papers," “U.S. Citizenship Affidavits" and popularly known as “protections”. These documents were issued to American seamen during the last part of the 18th century through the first half of the 20th century.This paper examines the lives of twenty American seamen as reflected in their protection certificates and related documents and what these convey about nautical life and its dangers in the early maritime world . These records which cover the period 1796-1822; more than any other, allow us to see beyond the stereotypical, happy - go –luck Jolly Tar of the “Great Age of Sail “of fiction and Hollywood. Instead these certificates reveal “the short and simple annals of the poor” for a life at sea as revealed in these certificates was anything but romantic. For these seamen their years afloat were rough, hard, low paying and dangerous, yet there is remains clear evidence that many loved and took pride in their occupation.1

1 Simon P Newman. “Reading the Bodies of Early American Seafarers.” The William and Mary Quarterly, vol. 55, no. 1, 1998, pp. 59–82. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/2674323. Accessed 19 Jan. 2020.

2 Ruth Priest Dixon "Genealogical Fallout from the War of 1812" Spring 1992, Vol. 24, No. 1 Prologue Magazine Genealogy Notes

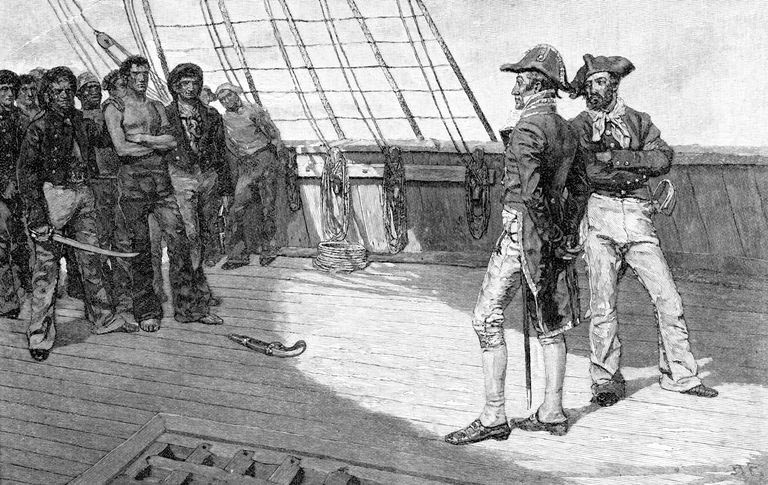

https://www.archives.gov/publications/prologue/1992/spring/seamans-protection.htmlImpressment: From the end of the Revolution until the conclusion of the War of 1812, American merchant crewman and some sailors on US naval vessels were at risk of impressments by British naval forces. Usually ships were stopped on the high seas and a party of British sailors and marines accompanied by their officers would board the vessel and take anyone who did not have documents proving their American nationality.

A conservative estimate of the number of American seamen impressed from 1796 to January 1812 is 9,991, a figure which compensates for duplications of names as they were found in lists made up by the Department of State and American agents for seamen in England. The most severe period was that from 1803 to 1812 when some 6,000 seamen were impressed. Not more than one·third of them were released before the outbreak of the war. Contemporary estimates ranged from 10, 000 to 50,000. Realistically speaking, however, it is still provocative to think that probably 750 to 1,000 were impressed annually between 1808 and 1812.3

3 The Naval War of 1812: A Documentary History 1812 Vol. 1 William S. Dudley editor (Naval Historical Center: Government Printing Office1985), 62

Before the creation of regular enlisted career paths and a retirement system; it was common for mariners to have served in both the merchant and naval service. After reviewing 128 beneficiaries of the Naval Asylum Philadelphia, for his Ungentle Goodnights Life in a Home for Elderly and Disabled Naval Sailors and Marines and the Perilous Seafaring Careers that Brought Them There, scholar Christopher McKee, found that 83 had or 65% had merchant service before turning to the navy as a career.4

4 Christopher McKee "Ungentle Goodnights: Life in a Home for Elderly and Disabled Naval Sailors and Marines and the Perilous Seafaring Careers that Brought Them There" (Naval Institute Press: Annapolis 2018), 95

The 1797 impressment of John Davis of Abel: Washington Navy Yard master blacksmith, John Davis of Abel (1774-1853) in this letter to the National Intelligencer of October 12, 1813, described his 1797 impressment (forcible recruitment) by the Royal Navy. Davis of Abel also notes his extremely rare good fortune, that the American Vice Consul was able to secure his rapid release.

To the editors of the National Intelligencer

In the month of February, 1797 I belonged to the Ship Fidelity, Captain Charles Weems, lying in the harbor of St. Pierre Martinique. About one o'clock Sunday morning, I was awakened by a noise on the deck, and going up, I found the ship in possession of a press gang. In a few minutes all hands were forced on board the Ceres frigate. We were ordered on the gun deck until day light by which time about 80 Americans were collected.

To the editors of the National Intelligencer

In the month of February, 1797 I belonged to the Ship Fidelity, Captain Charles Weems, lying in the harbor of St. Pierre Martinique. About one o'clock Sunday morning, I was awakened by a noise on the deck, and going up, I found the ship in possession of a press gang. In a few minutes all hands were forced on board the Ceres frigate. We were ordered on the gun deck until day light by which time about 80 Americans were collected.

Soon after sunrise, the ship’s crew was ordered into the cabin to be overhauled. Each was questioned as to his name &c when I was called on for my place of birth and I answered "New Castle, Delaware". The captain offered not to hear the last; but said "Aye Newcastle he's a collier; the very man. I warrant him a sailor" "Send him down to the doctor" Upon which a petty officer - whom I recognized as one of the press gang made answer "Sir I know this fellow" "He is a schoolmate of mine and his name is Kelly. He was born in Belfast Tom you know me well enough so don't sham Yankee anymore."

The next was a Prussian who had come aboard in Hamburg as a carpenter of the Fidelity in September, 1796 - He offered when questioned not to understand English; but answered in Dutch, upon which the captain laughed and said "this is no Yankee Send him down and let the quartermaster put in with the Dutchmen; they will understand him and the boatswain will learn him to talk English" He was accordingly kept. I was afterwards discharged by the order of Admiral Harvey on application of Mr. Craig, at that time American vice consul. I further observed that a full one third of the crew were impressed Americans.5

5 John G. Sharp, “John Davis of Abel Writes of being impressed into the Royal Navy” Meeting Minutes of Naval Lodge No.4 F.A.A.M. 1813 (Naval Lodge No. 4: Washington, DC 2013), np

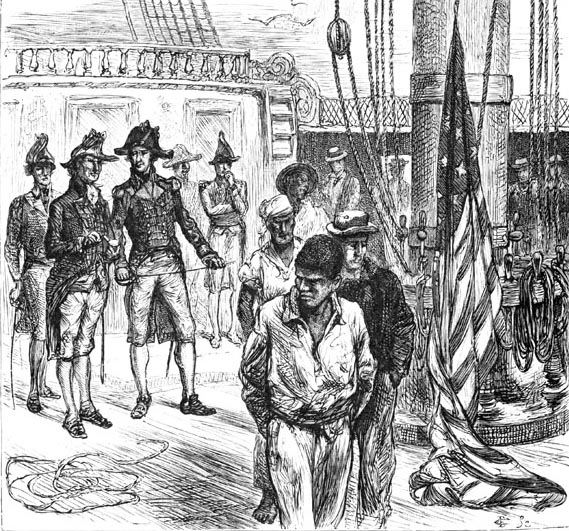

The Chesapeake/Leopard Affair: On 22 June 1807 an incident took place that dramatically caught public attention. This was the impressment of American seamen from the USS Chesapeake.6 The British vessel HMS Leopard seized four men Daniel Martin, John Strachan, William Ware and Jenkin Radford, claiming three were from HMS Melampus, and Jenkin Ratford, formerly on the HMS Halifax. Only Ratford was British-born. All four men had all previously served on American merchant vessels where they were impressed into the Royal Navy. They all subsequently deserted and had signed in to the U.S. Navy

6 Robert E. Cray "Remembering the USS Chesapeake: The Politics of Maritime Death and Impressment." Journal of the Early Republic 25, no. 3 (2005): 445-74. www.jstor.org/stable/30043338

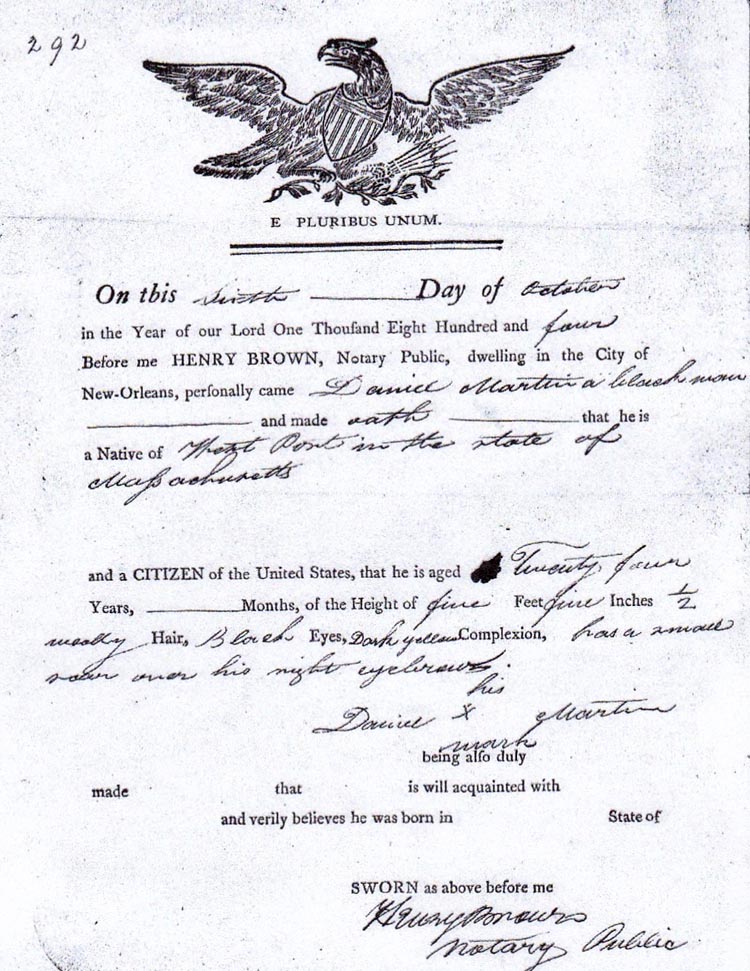

Daniel Martin claimed he was born in West Port, Massachusetts; he is described as age 24, 5’ 5’’ and ½ inches high with wooly hair, black eyes and dark yellow complexion with a small scar over his right eyebrow. Martin had served on the merchant vessel Caledonia and is described as “a colored man.”7 Newspaper accounts of the time state Martin was not born in the United States but brought to Massachusetts, (possibly enslaved) when he was six years old by mariner William Howland, possibly from Buenos Aires.8

7 The National Archives and Records Administration; Washington, D.C.; Proofs of Citizenship Used to Apply for Seamen's Certificates for the Port of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1792-1884 Certificate to Daniel Martin number 292, issued 6 October 1804, in the City of New Orleans

8 Hampshire – Federalist (Springfield MA) 01 October 1807, 2

William Ware was born enslaved on his father’s farm near Pipe Creek, Fredericks County Maryland. Ware served first on the commercial brig Neptune and later served eighteen months on the USS Chesapeake under Captain James Barron. He is described as “an Indian looking man.” John Strachan was born in Queen Anne’s County Maryland and had served on the merchant brig Martha Bland. He is described as a “white man about 5 feet seven inches high.” Daniel Martin and William Ware as blacks were not citizens and consequently are described as “native” Americans. The three American tars Martin, Ware and Strachan were court-martialed in Halifax Nova Scotia and each sentenced to 500 lashes but the penalty was later remitted. Jenkin Radford as British subject and deserter was tried by court martial and sentenced to death. He was executed at Halifax on 31 August 1807. At the time they were impressed William Ware and Daniel Martin said they had their protection certificate John Strachan said he had left his aboard the frigate. But the British officers simply ignored the certificates.13

13 Virginia Argus (Richmond VA) , 27 November 1807, 3

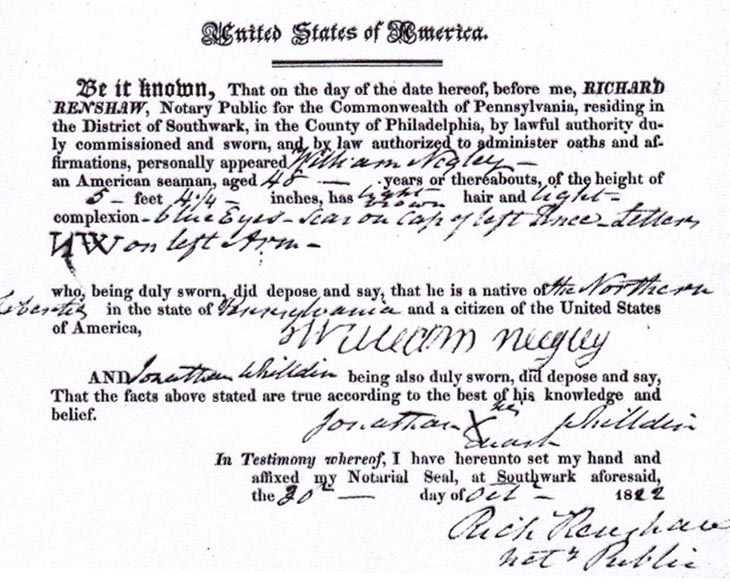

Identification: Protection paper descriptions were often vague or could apply to almost anyone; hence scars from work, small pox and other visible injuries were listed. Tattoos popular with sailors were often recorded as more reliable a form of identification. During this period the word “tattoo” was not commonly used and the affidavits instead say “marked” or “pricked.”14

14 Ira Dye " Seafarers: A Profile, 1812, Prologue" Journal of the National Archives, Volume 5, 9 1973

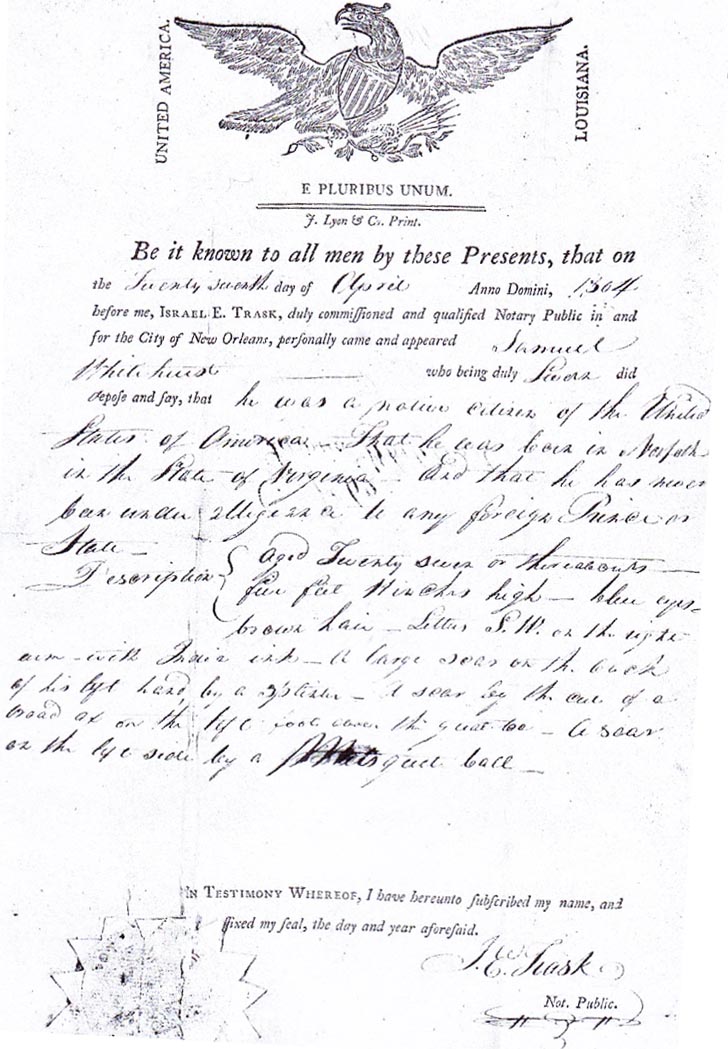

In an era with no photo images, tattoos by the early nineteenth century were one means of clearly establishing the identity of a seaman. “In a sample of 846 seamen who applied for protection certificates, from 1796 to 1803 an impressive 21% had designs, symbols, their names, dates and or initials pricked pricked into their skin.”15 For examples see the protection certificates of Samuel Whitehurst dated 27 April 1804, James Henry dated 28 December 1805, William King dated 23 March 1814 and that and of William Negley dated 30 October 1822. Both sailors had their initials inked into their arms. Tattoos were widespread with mariners. Novelist Herman Melville who served aboard whaling vessels and the frigate USS United States recounts the practice of “pricking” or tattooing aboard that vessel in 1844.

Others excelled in tattooing or pricking, as it is called on a man-of-war. Of these prickers, two had long been celebrated, in their way, as consummate masters of the art. Each had a small boxful of tools and colouring matter; and they charged so high for their services that at the end of the cruise they were supposed to have cleared upward of four hundred dollars. They would prick you to order: a palm-tree, or an anchor, a crucifix, a lady, a lion, an eagle, or anything else you might want.16

15 W. Jeffrey Bolster "African American Seamen in an Age of Sail" (Harvard University Press: Boston), 93

16 Melville, Herman "White Jacket or the World in a Man-of-War G" editor Thomas Tansselle (Library of America: New York 1983), 525A Dangerous Life: A sailor’s life was often harsh, dangerous and the risk of injury or death loomed large. See the certificate of Richard Adlum below. Injuries to seafarer’s bodies are often reflected in their certificates and a hallmark of a nautical life. “Unless they died in distant waters from disease to which their bodies did not have immunities or serve in ships that went down withal hands, the greatest danger that Marines and sailors of the early ninetieth century naval establishment faced was on the job injury.”17 & 18 Working aboard a vessel at sea has numerous dangers; most all the protection certificates include descriptions of cuts and scars to the hands from working line and rigging, see Charles Davis 1808 plus injuries to legs and knees, Elisha Hatts 1806 from falls on wooden decks. Not all injuries were accidental; most sailors carried knives used to cut rigging and splice lines. These workplace knives mixed with a daily grog ration or other liquor dramatically increased the danger violence in shipboard fracas and fights. For instance the protection certificate of “Henry Peterson’s listed “a scar on his forehead, & large scar on his throat where he was attempted to be murdered.” Another instance is the 1809 certificate of John Bowen which listed a “stab” scar on his left side, while the 1808 certificate of twenty year old sailor John Baker noted the “small scar on his left thigh occasioned by the cut of a cutlass. Sometimes such workplace fights were fatal as in the 1827 stabbing of Charles Morris a black seaman and cook aboard the Alert by seaman John Brooks resulted in Morris death, later found as “willful murder by a coroner’s jury.19

17 Christopher McKee Ibid, 192

18 John G. Sharp "The Disastrous Voyage: Yellow Fever Aboard the USS Macedonian & USS Peacock, 1822" http://www.usgwarchives.net/va/portsmouth/shipyard/yf1822.html accessed 2 January 2020

19 John G. Sharp "Letters from and to the Gosport Navy Yard 1826 -1828, 6 October 1827 James Barron to the Secretary of the Navy" http://www.usgwarchives.net/va/portsmouth/shipyard/nnysharp14.html accessed 31 December 2019Life at sea was no romantic cruise for the men of the lower decks. Their living spaces were damp and often cold.20 Disease, on the job injury, shipwreck and piracy were dangers faced by naval and merchant crews in the early nineteenth century. In the 1820’s piracy was still a real menace and of great concern to all who sailed in Caribbean waters. A total of twenty-seven American merchant ships were captured, between 1818 and 1821. In September 1821, three more American merchant ships were captured off Matanzas, Cuba. The crew of one ship was tortured and the vessel was set on fire, survivors were able to escape to shore in a boat. That same year, three men were killed on the second American ship and everyone on the third vessel which was also burned. The crews of American vessels plying these trade routes were on occasion armed. While the exact circumstances of their wounds are unknown both Samuel Whitehurst and William Negely certificates record their injuries as caused by musket balls.

20 Christopher McKee, Ibid 160

A Mariner Profile 1796-1822: To test what the surviving records can reveal, I collected a small sample of twenty certificates issued from 1796-1822. In the sample were 18 certificates issued in the Port of Philadelphia and two from New Orleans. All were native born; eleven listed Virginia as their place of birth, while seven listed Pennsylvania with one each from New Jersey and Massachusetts. In the sample three seafarers were clearly identifiable as free blacks John Davis dated 14 March 1805, James Forten Dunbar issued 10 July 1810, George McKinzie 31 January 1799. The sample confirmed life at sea was a young man’s world; the average age of the twenty individuals listed below was 25 years of age and modal 22 years. The youngest seamen being James Forten Dunbar age 10 and the two oldest mariners John George Blue and William Negley both 48 years of age. While this sample is far too small for a real assessment of average age, a larger study of 161 mariners from Boston Massachusetts dated 5 June through 5 September 1823 reflects an average age of 27.2 years.

The average height of our these 20 American seamen men was 5’ 6’’ inches; three inches inch shorter than today's average of 5’ 9’’. Simon Newman’s extensive study of the protection certificate’s issued in Philadelphia to long - term seafarers confirmed that these mariners as a group were significantly shorter than other American men. Newman based his study on the heights of 471 white mariners as listed on their certificates. He found that these men had a mean height of 5 feet, 6 inches tall. This was a striking 1.7 inches shorter than recruits of the Continental Army. While genetics plays a role in in how tall a person grows, the shorter height of these men indicate the straighten circumstances of their upbringing. The 15 black seamen in Newman’s sample did not allow for meaningful comparison. Newman concluded that the substantial difference in the mariner’s height, provides compelling evidence that urban born professional seafarers were drawn from the ranks of the poor whose diets and living conditions impaired their overall health and well-being. 21

21 Simon, Newman "Embodied History: The Lives of the Poor in Early Philadelphia" (University of Pennsylvania Press: Philadelphia2003) 109 - 110

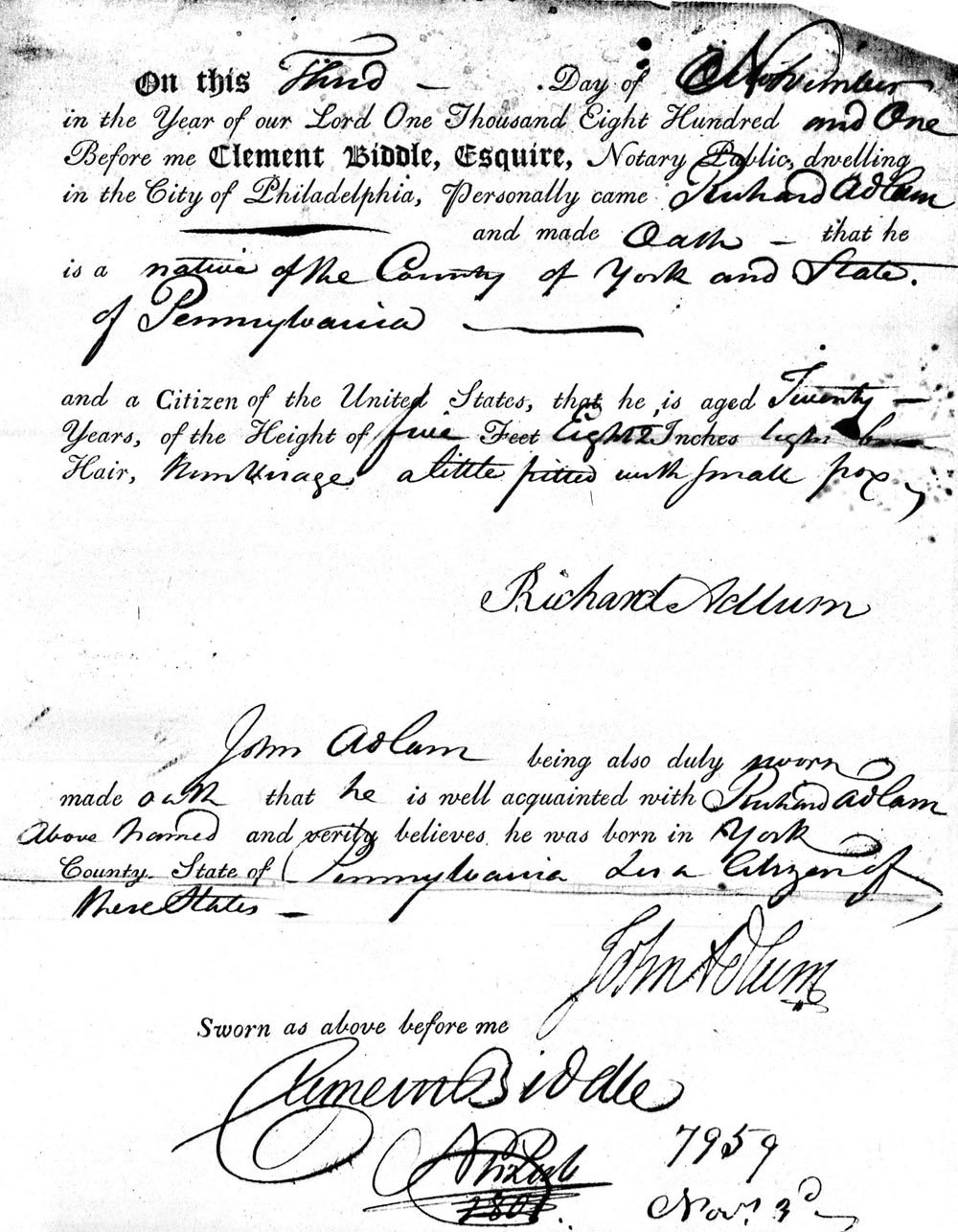

These twenty protections certifications in our samplebelow reveal how disease ravished early port cities. The faces and bodies of Richard Adlum 1801, William Barry 1804, John Bowen 1809 and John George Blue 1810 all were marked with small pox scars. On the positive side there is evidence of medical advances and the acceptance of inoculation for two certificates, those of Archibald Sinclair 1806 and James Forten Dunbar 1810 state they were identifiable by the “small pox inoculation scars on his left their arms” Dunbar was probably vaccinated at the insistence of his parents. For all seafarers small pox was among the most feared of the infectious diseases, for outbreaks had occurred in the port cities of Philadelphia and Norfolk, Virginia. The relative large size of both port towns enabled the virus to find a continual supply of susceptible individuals. Survivors like Barry, Bowen, Adlum and Blue often bore large, pitted scars, while other became blind.

Twelve of the twenty seamen in our sample or 60% possessed basic literacy that is they could write their name, while eight made their X mark. In his much larger sample Simon P. Newman found of the 480 mariners who left some evidence of their literacy or lack thereof: 184 were unable to write their own names making a total for 62% who possessed basic literacy.Transcription: This transcription was made from digital images of images of seaman’s protection certificates are from the National Archives and Records Administration; Washington, D.C.; Proofs of Citizenship Used to Apply for Seamen's Certificates for the Port of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1792-1884. And Proofs of Citizenship Used To Apply For Seamen's Protection Certificates for the Port of New Orleans, Louisiana, 1800, 1802, 1804–1812, 1814–1816, 1818–1819, 1821, 1850–1851, 1855–1857. 22

22 The National Archives and Records Administration; Washington, D.C.; Proofs of Citizenship Used to Apply for Seamen's Certificates for the Port of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1792-1884

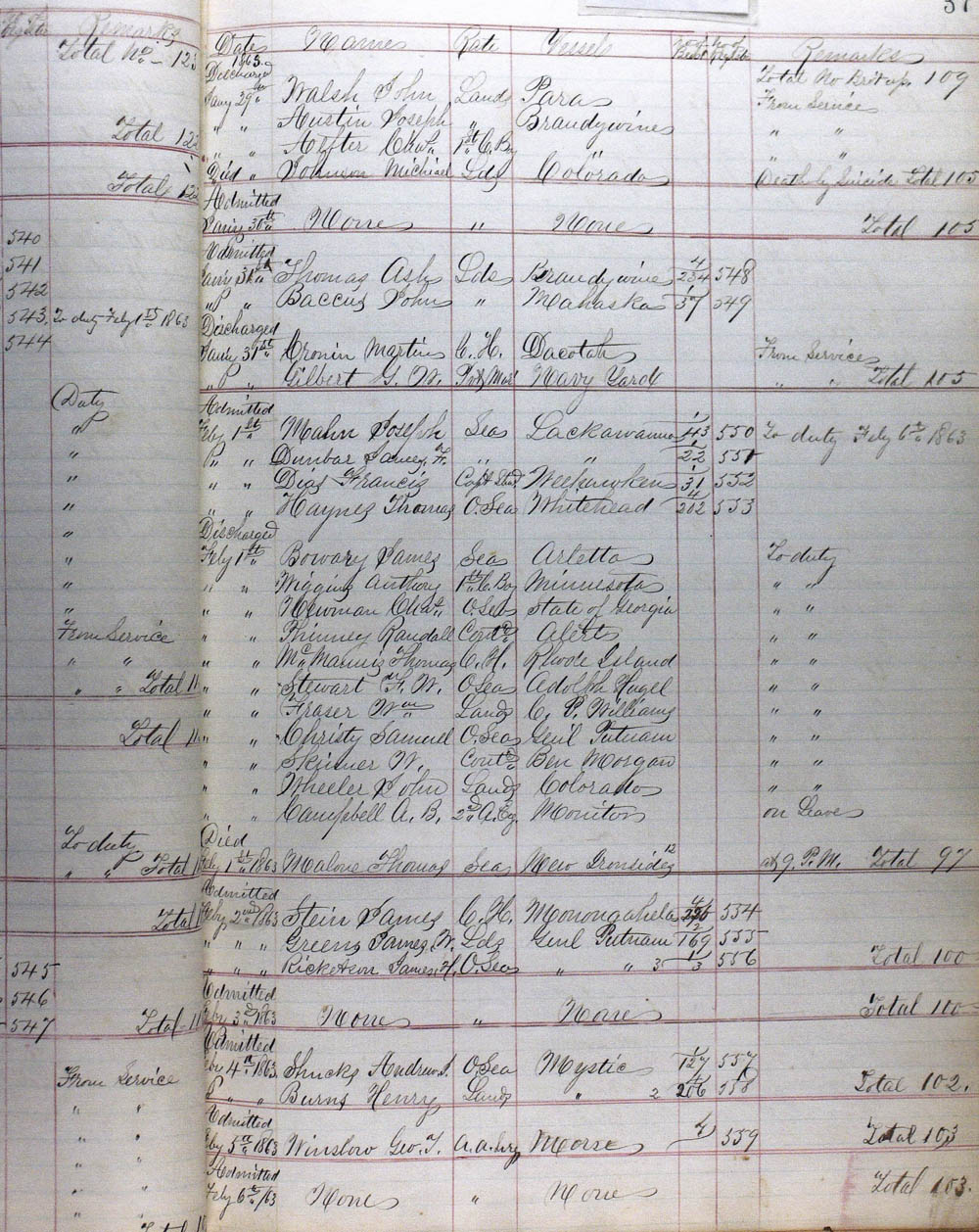

Naval hospital records for James Forten Dunbar are located in the Department of the Navy. Case Files for Patients at Naval Hospitals and Registers Thereto: Registers of Patients 1812–1929t textual records. Record Group 52: Records of the Bureau of Medicine and Surgery, 1812–1975, National Archives, Washington, D.C.

In transcribing these certificates, I have striven to adhere as closely as possible to the original in spelling, capitalization, punctuation, and abbreviation, superscripts, etc., including the retention of dashes and underlining found in the original. Racial designations such as “white man,” "mulatto," “black,” “yellow” etc., are those used in the original documents.23 Most transcriptions were made from certificates issued for the Port of Philadelphia, which has the best preserved and most informative of the surviving documents. Two certificates were transcribed from those issued at the Port of New Orleans, e.g. John George Blue and Daniel Martin.23 Ibid

Dedication: for David Megill 1753 -1807 of the Parish of Kirkmabreck, Kirkcudbright, Scotland, my ggg great grandfather, who was impressed into the British Navy at the age of 12 and eventually after suffering much privation and terror, escaped to New Jersey.

John G. M. Sharp, 1 January 2020

* * * * * * * * * *

Seamen’s Protection Papers Twenty Examples with Images and Discussion

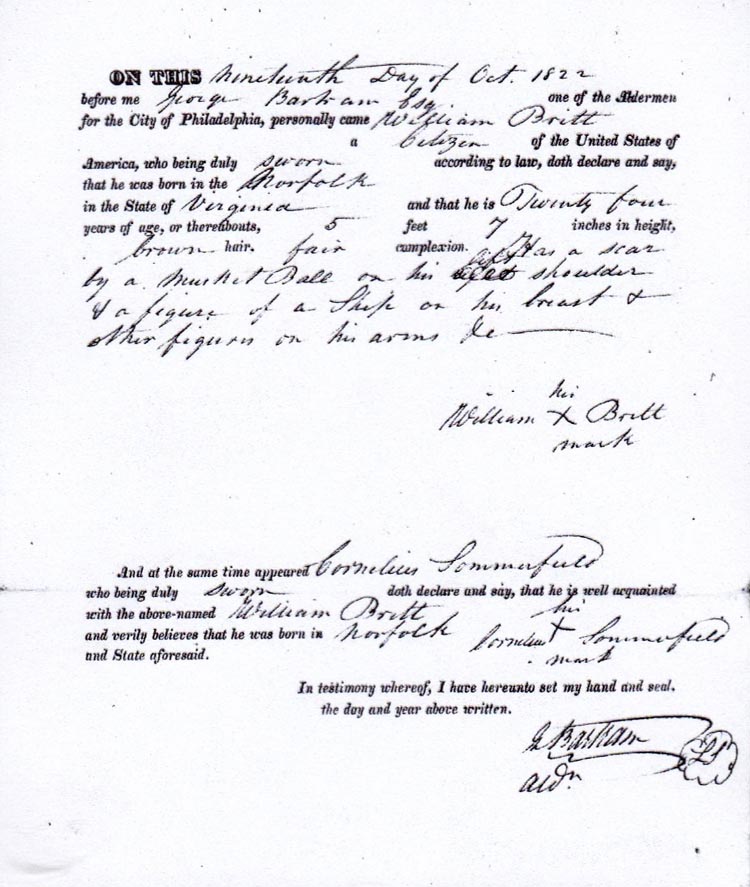

(click on images to enlarge in browser)These two protection certificates below were both issued in 1822. The 30 October 1822 certificate was for American seaman William Negley age 48 of Northern Liberties, Pennsylvania. The document carefully noted he was 5’ 4½ inches tall, had blue eyes brown hair and a scar on left knee cap and letters N W tattooed on his left arm. Negley was literate and signed his certificate. The certificate on the right was issued to American seaman William Britt of Norfolk Virginia on 19 October 1822. Britt was described as twenty five years of age, 5’ 7’’ inches with brown hair and fair complexion. Britt also had “a scar from a musket wound on left shoulder & figure of a ship on his breast & other figures on his arms etc.”

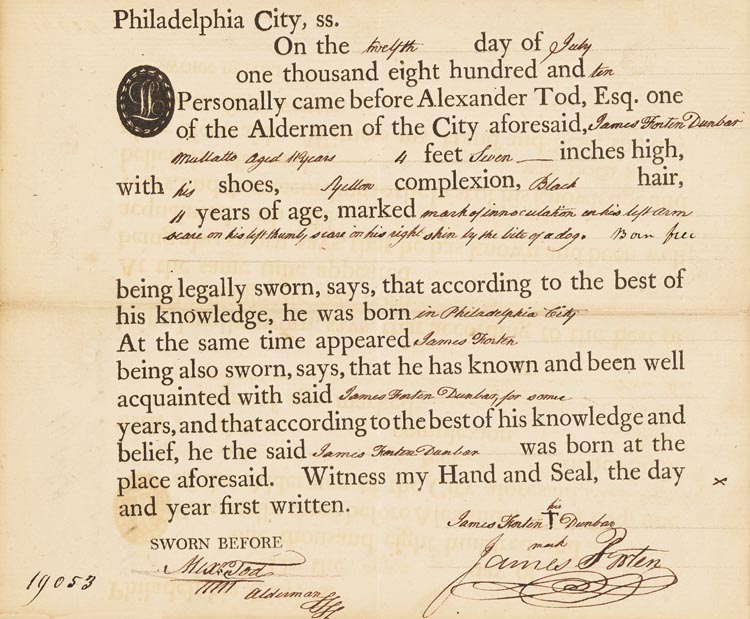

Black Seamen were a common presence on American merchant vessels during this period. Because protection papers were used to define freemen and citizenship, many black sailors such as John Davis dated 14 March 1805 and James Forten Dunbar issued 10 July 1810, used them also to show that they were freemen. These were particularly important documents if they were stopped by officials or slave catchers on land. These documents were also called “free papers" because they certified a mariner’s non-slave status. A recent review of protection certificates revealed the number of black men who were sailors: "By 1800, about 18 percent of the one hundred thousand Americans at sea were African Americans. It is possible to trace the number of African Americans in vessels belonging to the United States (an unknown number sailed for other nations) because Seamen's Protection Certificates were drawn up for all "citizens"—as they specified, such that blacks used them to claim citizenship they were denied — so that in theory they could not be seized by other nations.”24 A recently found document provides the number and percentage of African Americans entered into the U.S. Navy from 1 September 1838 to 17 September 1839 from five naval recruiting stations Boston, New York, Philadelphia, Baltimore and Norfolk was 1016 men for naval service, “of which 122 were black” or 12% of the total. 25

24 William Pencak, "Maritime Trades." Encyclopedia of African American History, 1619–1895: From the Colonial Period to the Age of Frederick Douglass. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006)

25 John G. Sharp "The Recruitment of African Americans in the U.S. Navy 1839" Naval History and Heritage Command

https://www.history.navy.mil/research/library/online-reading-room/title-list-alphabetically/r/the-recruitment-of-african-americans-in-the-us-navy-1839.html accessed 31 December 2019

The 12 July 1810 protection certificate issued in Philadelphia identities the bearer as James Forten Dunbar, a “mulatto” (a person of mixed white and black ancestry) age eleven, and height 4’ 7’’ inches tall.26 Dunbar was described as having black hair and yellow complexion. He had a small pox inoculation scar on his left arm and on his right shin the mark of a dog bite. Dunbar was born a “free man of color” in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, on 1 July 1799. Dunbar was the fourth and last child of William Dunbar and Abigail Forten Dunbar. His mother Abigail was the sister of famed African American abolitionist and sailmaker and father James Forten. Dunbar’s father William died young, and it’s his uncle, the renowned James Forten who signed for and made sure “Born Free” were included in the description. James Forten Dunbar attested the document by his X mark; it is unclear, if he ever became fully literate. Dunbar would spend most of his life as a sailor, aboard such naval vessels as the USS Constellation, USS Niagara, USS Brooklyn and the USS Tusacora.

26 John G. Sharp "Dr. Elnathan Judson’s 1823 report to the Secretary of the Navy on the successful vaccination of naval seamen in the Boston area for small pox with related demographic and ethnic data" http://www.usgwarchives.net/va/portsmouth/shipyard/judson.html

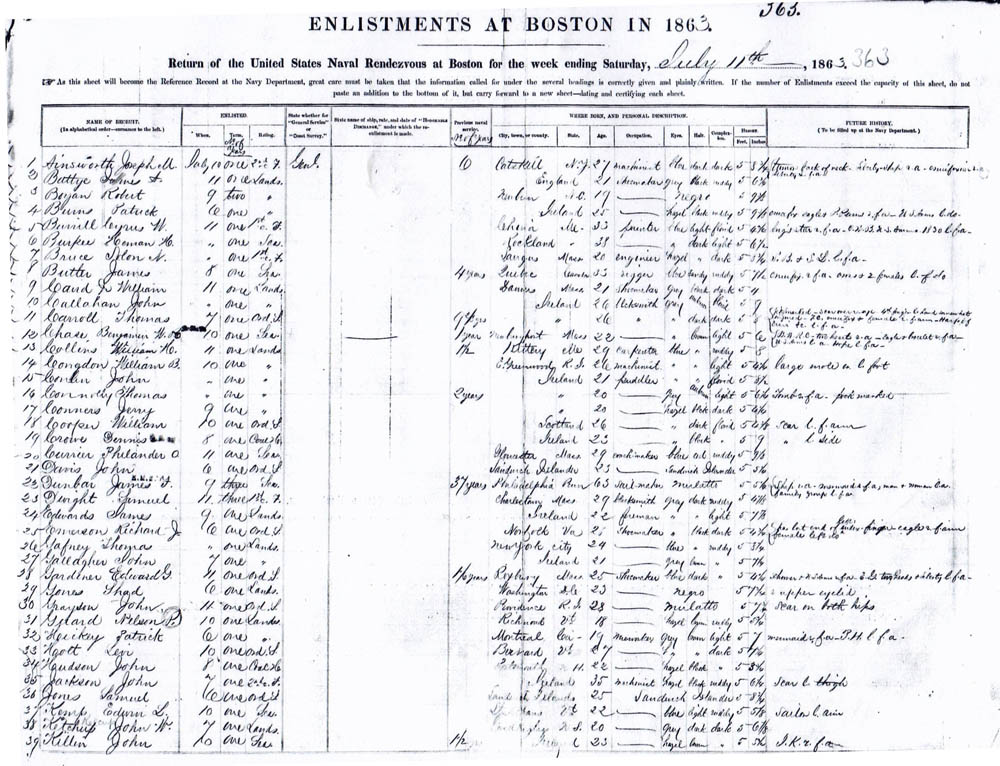

On 3 October 1856, suffering ill-health, he was admitted to the U.S Naval Asylum at Philadelphia, a refuge for retired sailors. However Dunbar was never a man to stay in one place and quickly longed to return to sea. At the beginning of the Civil War, the Union desperately wanted experienced seamen. In June 1863 Dunbar left the Asylum and traveled to New York City where on 12 June 1863, he attempted to reenlist. However he was denied enlistment probably due to age, which he reported as 64. Never one to despair or give up Dunbar returned to Philadelphia and went directly to the Boston Naval Rendezvous (recruiting center) where on 9 July 1863, he again reenlisted as a seaman, age as 63, for three years, on record of naval enlistments, he is recruit number 22 (above right). At the time of his reenlistment in July 1863, he is recorded as 5' 5'' and 1/4 inches tall. Dunbar listed 37 years of naval service and his occupation as sail maker. The recruiting officer noted Dunbar like many "old salts" was heavily tattooed with a ship, mermaids, a man and a woman and family group. While serving in the USS Tusacora he took part in some of the most memorable events of the Civil War serving as a sailor in Admiral David Dixon Porter's attack on Fort Fisher in December 1864 and January 1865. James Forten Dunbar died 26 November 1870 and was buried at Philadelphia Naval Asylum burial grounds.27

27 Christopher McKee, Ibid 108-120

A Dangerous Occupation: “Lost at sea “was a familiar epitaph. Some seamen were swept overboard in storms or gales, while still others fell the mast or rigging while setting sail and very few could swim. During the period 1793-1815 an estimated 2000 ships were lost at sea.28 & 29 Once such person was Richard Adlum (1781–1801/02) his protection certificate was issued in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, on 3 November 1801. He was born near York Pennsylvania and died at sea. Adlum was from a middle class family, his father and grandfathers were both elected officials. He is described as twenty years of age, 5’ 8 inches tall, light brown hair, “nom visage [the face] a little pitted with small pox.” Richard's brother, Major John Adlum (1759-1836), signed for the younger man shortly before he boarded a merchant vessel bound for England during the dangerous winter season. Richard was eventually reported (1802) as lost at sea. Richard's old brother, Major Adlum, a veteran of the American Revolution, wrote that he too had once considered going to sea, but his conversations with his uncle had made him realize the full dangers of a maritime career.30 He wrote “my inclination leaned towards my going to sea, wherefrom my vanity and the good opinion I had of myself. I thought I could learn a profession by which I might advance myself in the world. I mentioned this circumstance to my uncle who informed me that there were several young men from Town that went to sea and were in the British prisons. As I had witnessed their treatment of prisoners, it somewhat cooled my ardor.”31

28 Terence Grocott "Shipwrecks of the Revolutionary and Napoleonic Eras 1793 -1815" ( University of Michigan Press:Ann Arbor 1997), viii

29 This example is from the Journal of Midshipman James Pity, for 1 November 1798 “First part these 24 hours, the Gale Increasing from the W.N.W., with a Dangerous Sea. … James Johnson Ord Seaman was lost overboard by Accident but it was Impossible to give him any assistance and poor fellow he found a watery grave.” For seamen who fell to their deaths from the mast or rigging while setting sail see USS Constitutions log, 8 November 1798, 27 February 1799 and 27 September 1803 as only a few could swim. "The Deck Log, Journals & Letters of the Frigate USS Constitution 1798-1815" editor John G. Sharp http://www.usgwarchives.net/va/portsmouth/shipyard/constitution-decklog-1.html accessed 3 January 2020

30 Helen Whitacre Burke "Mostly About the Whitacre and Warner Families, 1985" p 88

31 John Adlum, (editor Howard H. Peckham) "Memoirs of the Life of John Adlum in the Revolutionary War" (The Caxton Club: Chicago1968) and an unpublished section of John Adlum manuscript Manuscripts Division, William L. Clements Library, University of Michigan, the Schoff Revolutionary War Collection, which contains the unpublished manuscript (np) of John Adlum’s autobiography from which this selection was transcribed.

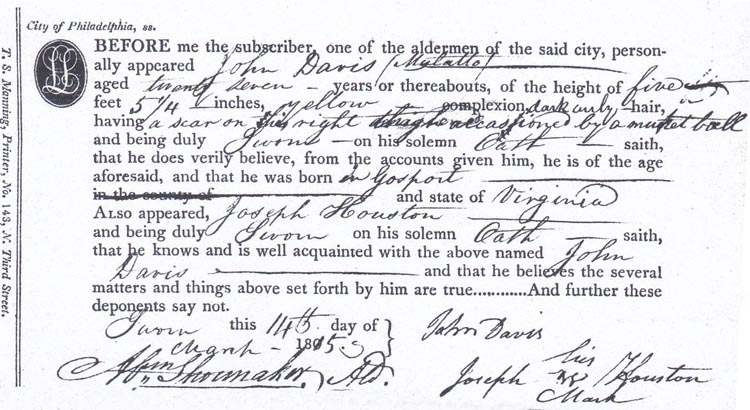

Scars and Wounds: The protection certificate below right dated 14 March 1805 was issued to John Davis. Davis is described as born in Gosport, Virginia, twenty seven years of age, a “mulatto “ [a person of mixed white and black ancestry] with dark curly hair, and “yellow complexion. “Davis signed his own certificate, while his friend Joseph Houston made his mark or X. Davis signature is clear and well written reflecting education. How did John Davis learn to read and write? The segregated history of education in early Norfolk made it difficult, but most likely in the antebellum era at an African American church and or Sunday school.

Davis may have seen prior military action as he is listed as having a scar on the right thigh caused “by a musket ball”. Similarly is the protection certificate dated 27 April 1804 issued to Samuel Whitehurst. Whitehurst is described as age twenty seven, 5’ 11" tall with brown hair and blue eyes and a native of Virginia. The certificate notes the “letters S.W. on the right arm with India ink” and an assortment of former injuries. Whitehurst injuries include “a large scar on the back of his left head by a splinter and a scar by the cut of a broad ax on the left foot and a scar on the left side by a musket ball.”

* * * * * * * * * *

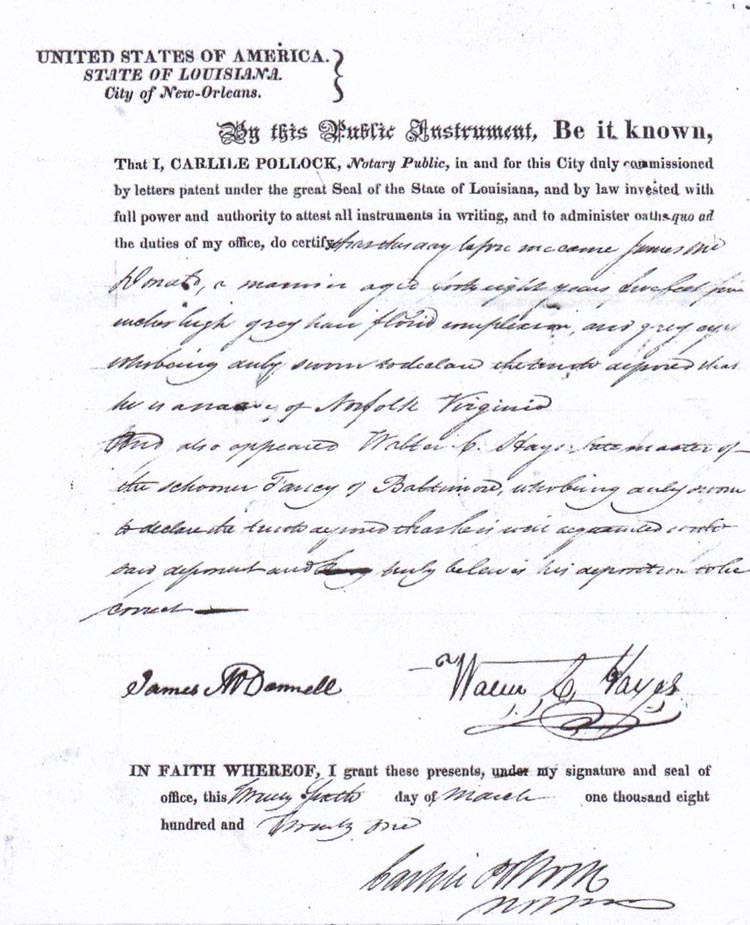

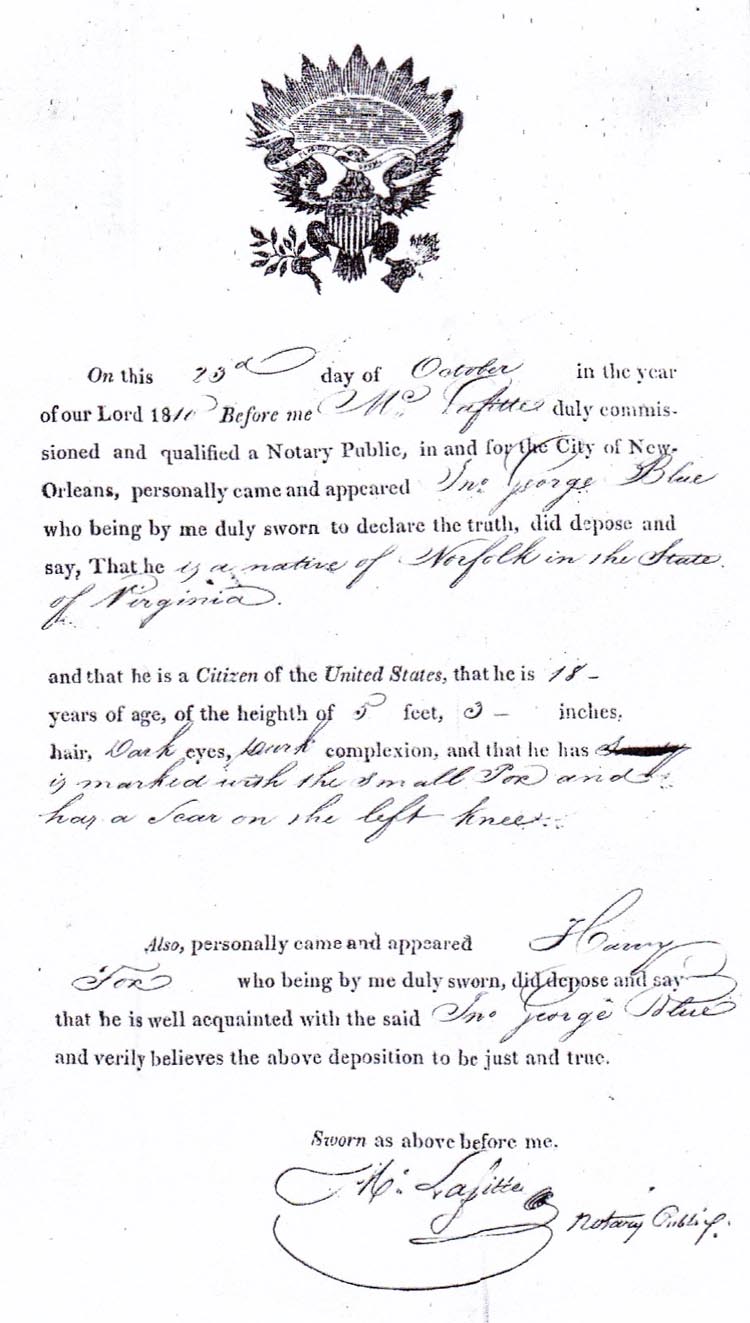

The protection certificate (below left) was issued 4 March 1821 to James McDonnell, age 48, a native of Norfolk, Virginia. McDonnell is described as 5’ 5’’ tall, with grey hair, grey eyes and of florid complexion. Walter B. Hayes, the former master of the schooner Fancy, signs as a witness to the accuracy of McDonnell’s certificate. McDonnell and Hayes both were literate and affixed their signatures to the certificate. The protection certificate (below right) was issued in New Orleans Louisiana on 23 October 1810 to John George Blue. Blue is described as an American seaman and native of Norfolk, Virginia. He is listed as eighteen years of age, 5’ 3” tall, with dark hair, and dark complexion. The recorder noted that Blue “is marked with small pox and has a scar on his left knee.” Blue grew up in Norfolk, Virginia, a city that had Anti-Inoculation Riots in 1768 -1769.32 The document is attested by Henry Fox, although neither Blue nor Fox have affixed their signatures.

32 The 1768–1769 Norfolk Anti–Inoculation Riots & Following Court Cases http://www.masonslegacies.org/exhibits/show/a-comparative-analysis-of-the-/introduction-----the-1768-----

accessed 3 January 2020.Dye, Ira. “Early American Merchant Seafarers.” Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, vol. 120, no. 5, 1976, pp. 331–360. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/986266. Accessed 6 Jan. 2020.

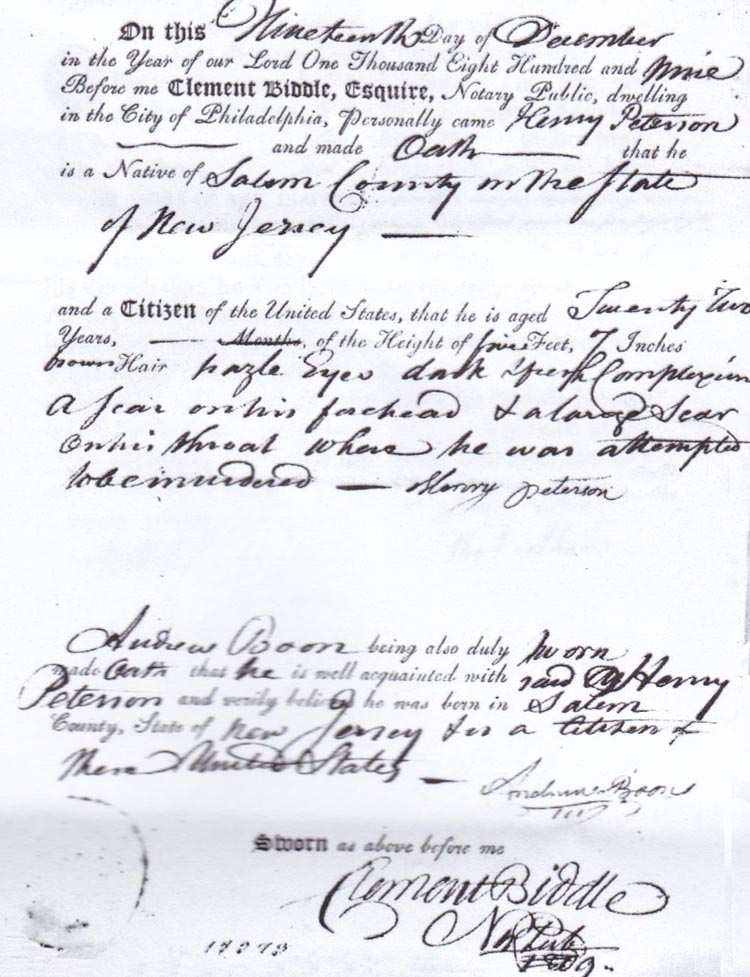

The protection certificate issued 19 December 1809 in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, (below left ) was for Henry Peterson. Peterson was born in Salem County, New Jersey, and is described as 22 years of age, 5’ 7’’ tall, brown hair, hazle eyes, dark complexion and “a scar on his forehead, & large scar on his throat where he was attempted to be murdered.” Peterson is literate and afixed his siganture to the document.

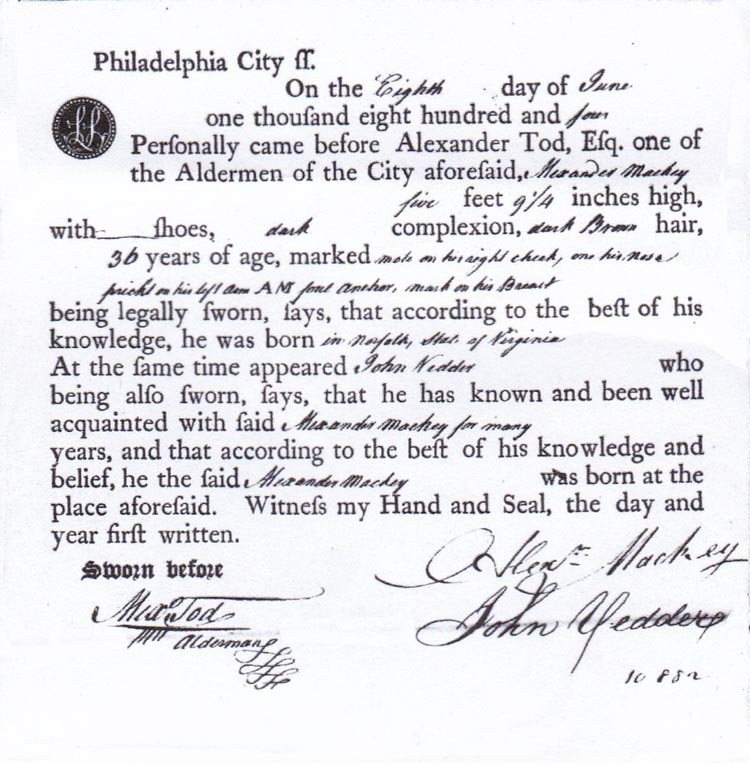

The protection certicate issued on 8 June 1804 in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, (below right) was for Alexander Mackey. Mackey was born in Norfolk Virginia, and is described as 36 years of age, 5’ 9¼" with a mole on his right cheek, one on his nose, and “pricked on his left arm A M, foul anchor mark on his breast.”

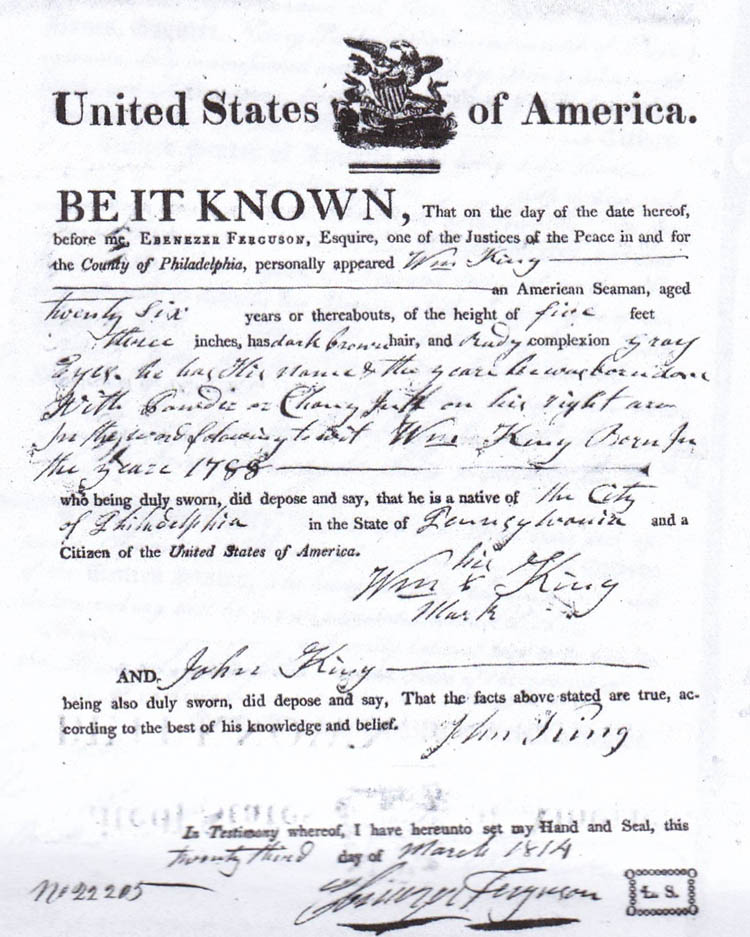

The protection certificate (below left) was issued on 23 March 1814 in Philadelphia Pennsylvania to William King. King is described as age 26, 5’ 3’’ inches tall, with dark brown hair, ruddy completion and grey eyes. Philadelphia Justice of the Peace, Ebenezer Ferguson, noted King “has his name & the year he was born done in Powder or Chimney Ink on his right arm in the words to wit Wm King Born in the Year 1788” William King certified the document thus “ his Wm X King mark. While William King was probably illiterate, he had his name and date of birth, inked into his arm that in the event of his death, his body would be properly identified and buried.

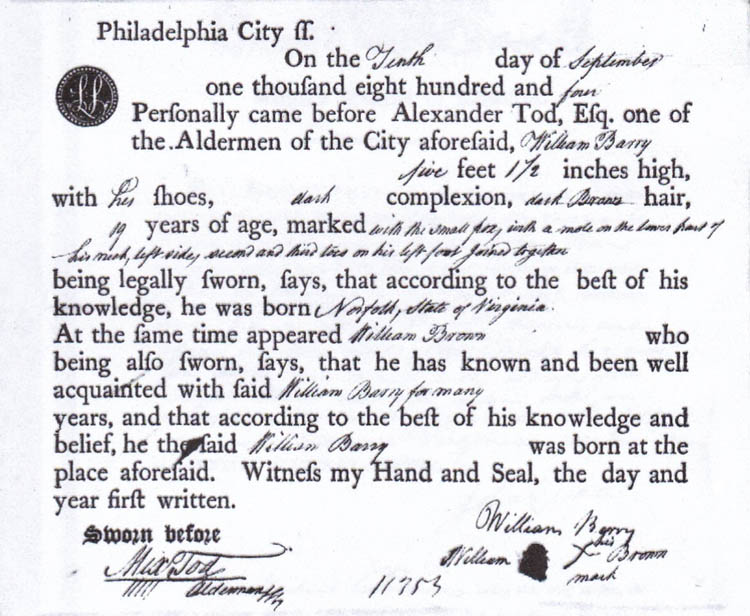

The protection certificate (below right) was issued in Philadelphia on 10 September 1804 to William Barry. Barry is described as five feet ½ inches high, dark complexion, dark Brown hair, 19 years of age, marked with the small pox, with a mole on the lower part of his neck, left side, second and third toes on left foot joined together. He was born in Norfolk, State of Virginia. William Barry certified his certificate by signing his name, while his witness William Brown made his X mark

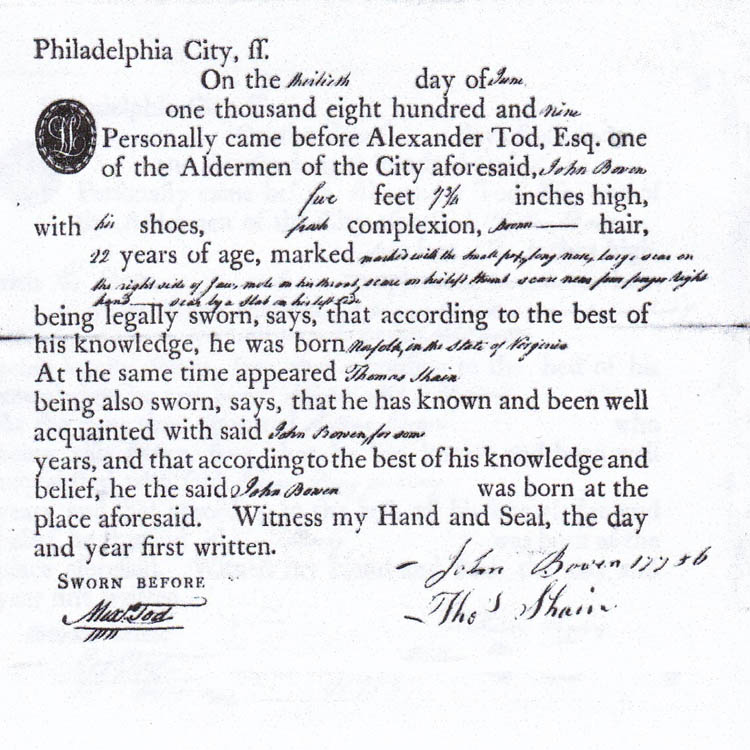

This protection certificate (below left) was issued in Philadelphia on 13 June 1809 to John Bowen. Bowen is described as five feet 7 ¾ inches high, Brown hair, 22 years of age, marked with the small pox, long nose, large scar on right side of jaw, mole on his throat, scar on his left throat, scar near right hand - scar by a stab on his left side. Bowen was born in Norfolk, in the State of Virginia. Bowen signed his name, as did his witness Thos. Shain.

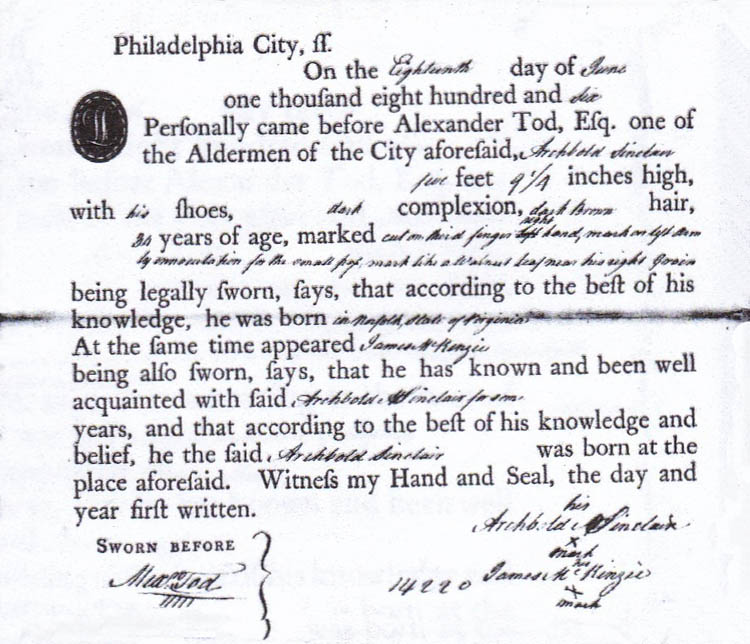

This protection certificate (below right) was issued in Philadelphia on the 18 June 1806 to Archibald Sinclair. Sinclair is described as 5 feet 9 ¼ inches high, with dark complexion, dark brown hair and 34 years old. He is listed with a cut on third finger right hand and mark on left arm by inoculation for the small pox and mark like a walnut leaf across his groin. The certificate further states Sinclair was born in Norfolk Virginia. Sinclair and his witness James Mc Kinzie both attested the document with their X mark

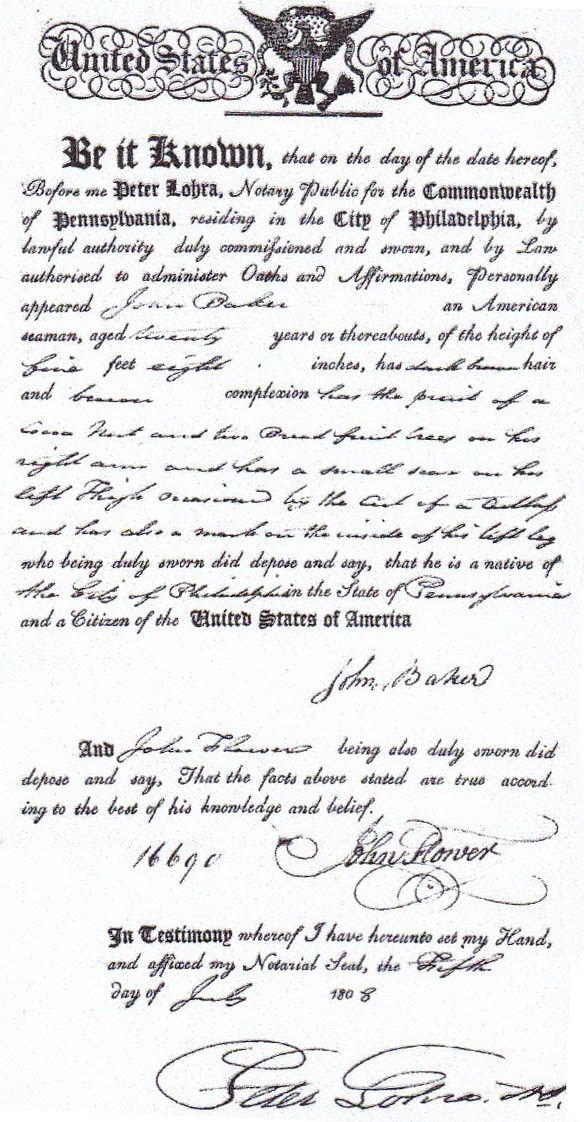

This protection certificate (below left) was issued in Philadelphia on 5 July 1805 to John Baker. Baker is described as a native of Philadelphia and a citizen of the United States. He is listed as twenty years of age, five feet eight inches tall, long brown hair, and brown complexion. He has two bread fruit trees on his right arm and has a “small scar on his left thigh occasioned by the cut of a cutlass and also has a mark on the inside of his left leg." Baker attested the certificate with his signature and as did his friend John Plover.

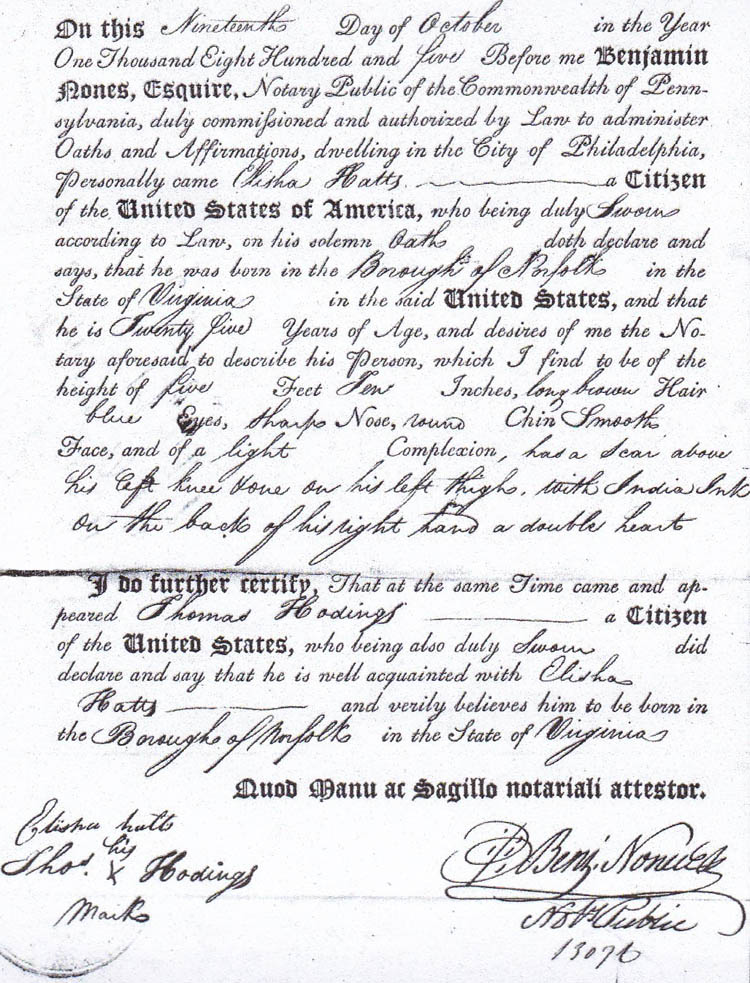

This protection certificate (below right) was issued in Philadelphia on 19 October 1805 to Elisha Hatts. Hatts is described born in the Borough of Norfolk in the State of Virginia and a citizen of the United States. Hatts is listed as twenty five years of age, five feet ten inches tall, long brown hair, blue eyes, sharp nose, round chin, smooth face and of light complexion, has a scar above the left knee & one on his left thigh, with India inked on the back of his right hand a double heart. Elisha Hatts attested the certificate with his signature while his friend Thos. Hodings made his X mark.

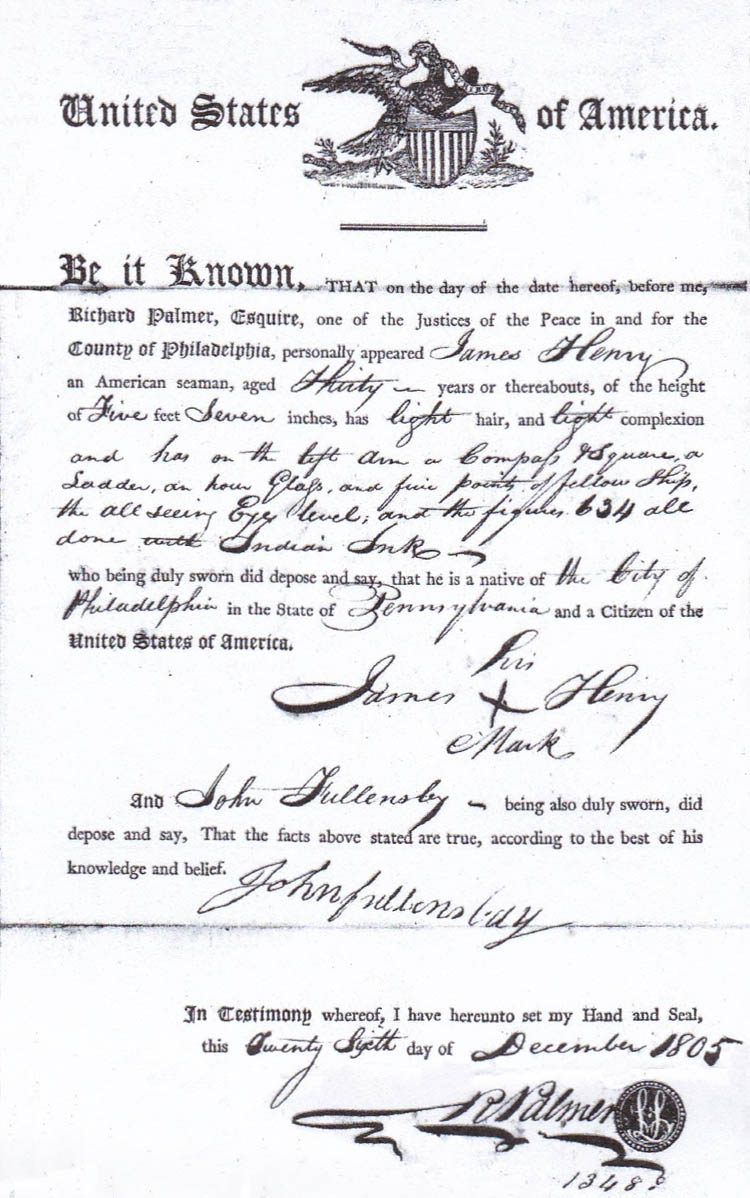

This protection certificate (below left) was issued in Philadelphia on 28 December 1805 to James Henry. Henry is described as thirty years of age five feet 7 inches high, light hair, light complexion. Henry has on the left arm, a Compass, Square, a Ladder, an hour Glass and five points of fellowship , the all seeing Eye level and the figure 634 all done in India Ink- James Henry swears he is a native of Philadelphia. James Henry attested his certificate with his X mark, his acquaintance John Fullensby attested the same with his signature.

James Henry tattoos were unusual for he was a member of the fraternal order of Freemason’s who proudly displayed their symbols such as the “Compass & Square,” the single most identifiable symbol of Freemasonry. Both the square and compasses are architect's tools and are used in Masonic ritual as emblems to teach symbolic lessons. Henry also had his Philadelphia Lodge number 634 tattooed on his body. Such membership suggests that Henry was more than a common sailor for membership in the Philadelphia Lodge by the mid 1780’s ran as high as $30 – as much as a month’s salary for a common seaman.3333 Newman Ibid 114 -115

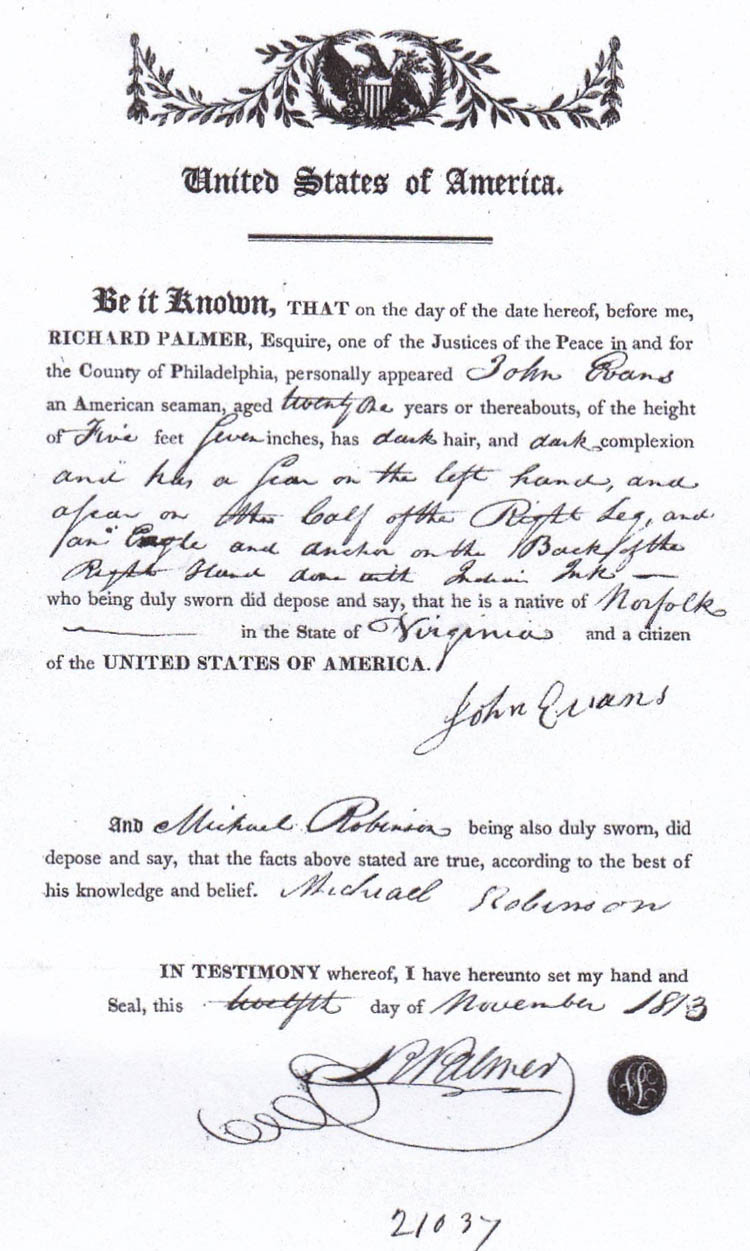

This protection certificate (below right) was issued in Philadelphia on 12 November 1813 to John Evans. Evans is described as twenty one years of age, five feet 7 inches high, dark hair, dark complexion. Evans is listed as having a scar on the left hand, and a scar on the calf of the right leg, and “an Eagle and anchor on the Back of the Right Hand done with Indian ink.” Evans was born in Norfolk, in the State of Virginia. Evans signed his name, as did his witness Michael Robinson.34

34 Ira Dye “The Tattoos of Early American Seafarers, 1796-1818.” Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, vol. 133, no. 4, 1989, pp. 520–554. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/986875. Accessed 13 Jan. 2020.

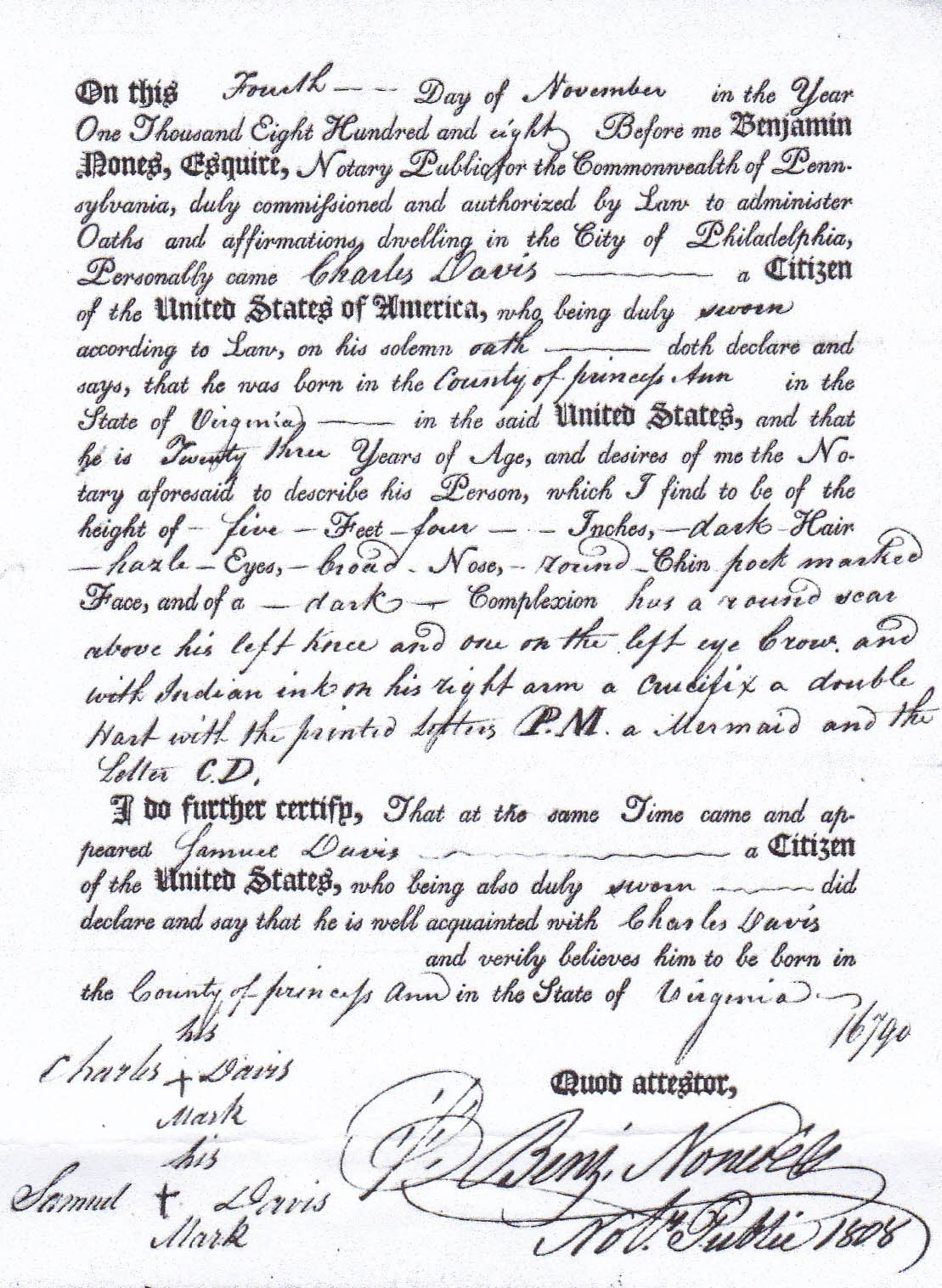

This protection certificate (below left) was issued on 4 November 1808 in Philadelphia to Charles Davis. Davis is described as a citizen of the United States, and a native of Princess Ann County, Virginia. Davis was listed as 23 years of age, five feet four inches, dark hair, hazel eyes, broad nose, round chin, pock marked face, and of dark complexion has a round scar above his left knee and one on the left eye brow and with Indian ink on his right arm a crucifix, a double heart with printed letters P. M., a Mermaid and letters C.D. Charles Davis attested this document by making his X mark as did Samuel Davis.35

35 Ibid, Dye “The Tattoos …”p.542 By far the most prevalent tattoos in Ira Dye’s classic study of 893 certificates of sailors with ink markings were their initials and names. The reason as Dye points out was wholly practical. In the days before DNA or dog tags , a tattoo, insured the sailor’s name or initials might be read were his body washed ashore after a ship wreck or if he was swept overboard.

Among tattooed seamen the crucifix inked on Charles Davis was by far the most common religious tattoo.36 Davis, while illiterate, may have been a Roman Catholic who derived comfort from this symbol of salvation. Herman Melville while a sailor aboard the frigate USS United States (1844) was a close observer of nautical life and customs. He wrote that “the Roman Catholic sailors on board had at least the crucifix pricked on their arm, and for this reason. If they chanced to die in a Catholic land they would be sure of a decent burial in consecrated ground…”

36 Newman Ibid, 119

Melville also noted that “Many sailors not Catholic were anxious to have the crucifix painted on them owing to a curious custom of theirs. They affirm - some of them – that if you have that mark tattooed upon all four limbs, you might fall overboard among seven hundred and seventy thousand white sharks and not one of them would do so much as dare to smell your little finger.”37

37 Melville Ibid, 525

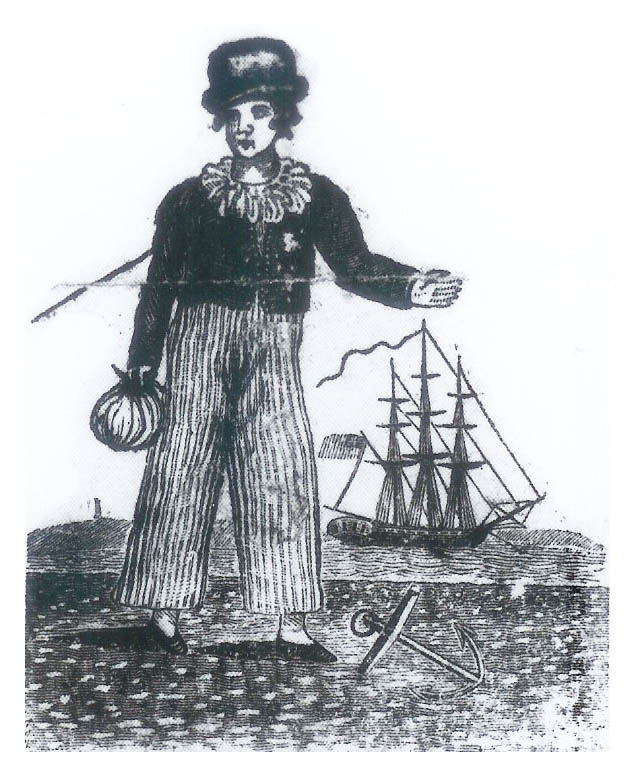

The lament (below) “The Impressment of an American Sailor Boy” 1814 was composed by John De Wolf for the 4 July 1814 ceremony aboard the HMS prison ships Crown Prince and Nassau and “was sung by American Prisoners.” The verses are a lament for a young sailor, “Fast to an end his miseries draw the deadly flush of his cheeks. On his pale brow the cold dew hung He sighed and sunk upon the deck.” This tearful song was included in a book by Dr. Benjamin Waterhouse which portrayed and described the plight of American sailors confined to British prison hulks in Bermuda during the War of 1812 and slowing wasting away. It described what many American prisoners had experienced, the impressment of an American sailor by a British man of war, the tearing up of his legal protection and of his sinking under a broken heart.38

38 The plight of American prisoners of war held in Bermuda during the War of 1812, is today largely unknown. At least 2,875 American seamen and marines were held in Bermuda many on so call hulks, Royal Naval vessels which were used as prisons. These ships were known for their brutal treatment and deplorable sanitary conditions which led to many deaths. See Benjamin Waterhouse, M. D. “A Journal of a Young Man of Massachusetts (Boston, Rowe & Hooker [sic] 1816. New York, Reprinted, Abbatt, 1911), 140-141

"The Impressment of an American Sailor Boy"

sung on board the British Prison Ship Crown Prince

the Fourth of July 1814 by a number of American Prisoners

The youthful sailor mounts the bark,

And bids each weeping friend adieu:

Fair blows the gale, the canvass swells:

Slow sinks the uplands from his view.Three mornings, from his ocean bed,

Resplendent beams the God of day:

The fourth, high looming in the rain,

A war-ship's floating banners play.Her yawl is launch'd; light o'er the deep,

Too kind, she wafts a ruffian band:

Her blue track lengthens to the bark,

And soon on deck the miscreants stand.Around they throw the baleful glance:

Suspence hold mute the anxious crew—

Who is their prey? poor sailor boy!

The baleful glance is fix'd on you.Nay, why that useless scrip unfold?

They danm'd the "lying yankee scrawl,"

Torn from thine hand, it strews the wave—

They force thee trembling to the yawl.Sick was thine heart as from the deck,

The hand of friendship waved farewell;

Mad was thy brain, as far behind,

In the grey mist thy vessel fell.When sick at heart, with "hope deferr'd."

Kind sleep his wasting form embrac'd,

Some ready minion ply'd the lash,

And the lov'd dream of freedom chas'd.Fast to an end his miseries drew:

The deadly hectic flush'd his cheek:

On his pake brow the cold dew hung,

He sigh'd, and sunk upon the deck!The sailor's woes drew forth no sigh:

No hand would close the sailor's eye:

Remorseless, his pale corpse they gave,

Unshrouded to the friendly wave.And as he sunk beneath the tide,

A hellish shout arose;

Exultingly the demons cried,

Suffer all Albion's Rebel Foes!"

* * * * * * * * * *

John G. "Jack" Sharp resides in Concord, California. He worked for the United States Navy for thirty years as a civilian personnel officer. Among his many assignments were positions in Berlin, Germany, where in 1989 he was in East Berlin, the day the infamous wall was opened. He later served as Human Resources Officer, South West Asia (Bahrain). He returned to the United States in 2001 and was on duty at the Naval District of Washington on 9/11. He has a lifelong interest in history and has written extensively on the Washington, Norfolk, and Pensacola Navy Yards, labor history and the history of African Americans. His previous books include African Americans in Slavery and Freedom on the Washington Navy Yard 1799 -1865, Morgan Hannah Press 2011. History of the Washington Navy Yard Civilian Workforce 1799-1962, 2004.

https://www.history.navy.mil/content/dam/nhhc/browse-by-topic/heritage/washington-navy-yard/pdfs/WNY_History.pdf

and the first complete transcription of the Diary of Michael Shiner Relating to the History of the Washington Navy Yard 1813-1869, 2007/2015 online:

https://www.history.navy.mil/research/library/online-reading-room/title-list-alphabetically/d/diary-of-michael-shiner.html

His most recent work includes Register of Patients at Naval Hospital Washington DC 1814 With The Names of American Wounded From The Battle of Bladensburg 2018,

https://www.history.navy.mil/research/library/online-reading-room/title-list-alphabetically/r/register-patients-naval-hospital-washington-dc-1814.html

The last three works were all published by the Naval History and Heritage Command. John served on active duty in the United States Navy, including Viet Nam service. He received his BA and MA in History from San Francisco State University. He can be reached at sharpjg@yahoo.com* * * * * * * * * *

Norfolk Navy Yard Table of Contents

Birth of the Gosport Yard & into the 19th Century

Battle of the Hampton Roads Ironclads