The Cosmopolitan, A Monthly Illustrated Magazine, Volume XV, The Cosmopolitan

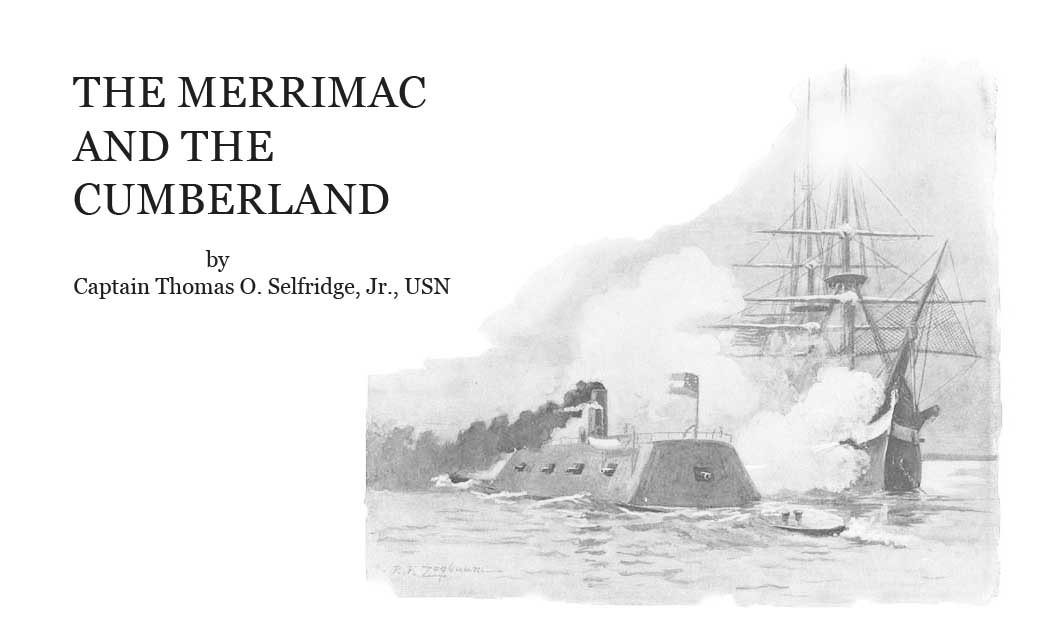

Press, 1893, pp 176-184.On a quiet Sunday morning, the 9th of March, 1862, the people of the North were startled with the intelligence of the fight between the Cumberland and the Merrimac, and, as later on, the details of the battle became known, the heroic resistance of the former and the terrible power exerted by the latter, produced a profound impression and a vague sense of terror that probably was unequalled at any period before or since, during the Civil war.

Great armies met afterwards in deadly conflict, the losses on both sides were far greater, but the unexpectedness of the event, the bravery shown by the Cumberland, the appearance of a terrible engine of war whose existence was unsuspected, the providential arrival of the Monitor when the Merrimac had the whole wooden navy at her mercy, the combat between the two armored vessels, the first in history, all unite in stamping the 8th and 9th of March, 1862, as two days at least as memorable as any in the war.

It is a singular coincidence that both the Merrimac and the Cumberland were launched from the Boston navy-yard, the former in 1856, the latter in 1842.

At this date and for many years the armament of the Cumberland consisted of ten 8-inch, and eighteen 32-pounder guns on the gun-deck, and sixteen light 32's on the spar-deck, and she belonged to the frigate class which contained the Potomac, Brandywine, Columbia, Savannah, Raritan, St. Lawrence, Santee and Sabine. She was always a favorite, and served as the flag-ship of Commodore Jos. Smith in command of the Mediterranean squadron, and Commodore Conover of the African squadron. About 1856 she was razeed, that is, cut down into heavy sloop-of-war. Her gun-deck battery was exchanged for twenty-two 9-inch shell guns, and the spar-deck battery of 32's removed, and two 10-inch pivot guns, one at the bow and one at the stern, put in their places. This was the battery at the time of the fight, except that for the after 10-inch there had been substituted a 70-pounder Dahlgren rifle gun.

In September, 1860, the Cumberland was commissioned as the flag-ship of the Home squadron at Portsmouth, N. H., Commodore Pendergrass commanding, myself and Lieutenant (now Colonel) Heywood of the marine corps, being the only officers that remained by the ship from this date to her final destruction. Her crew, however, enlisted mostly in Boston and vicinity, had suffered but few changes beyond the usual ones of a long enlistment. They were proud of their ship, they had the mutual dependence upon each other arising from long associations, and they had been subjected to a discipline which gave them great faith in themselves and in the armament of their ship. They really believed themselves invincible, and indeed could they have had a fair fight would have shown themselves to be such. With but few officers, for the first time in their lives exposed to a terrible shell fire, seeing their comrades mangled and dead before them, the manner in which these decimated guns' crews stood unflinchingly at their guns, with the water pouring over the decks, the ship trembling in the last throes of her disappearance, until the word was passed from their officers, "Every man look out for himself," just before the ship went down, was not only sublime, but ought to embalm the name ''Cumberland'' in the heart of every American. History gives no example of braver resistance in the face of utter hopelessness, a sterner feeling of "never surrender," than was shown by the Cumberland on the 8th of March, 1862. Does it not seem strange, then, that this name should have been allowed to disappear from the navy list? and yet such is the case, and the memory of her deeds are almost unknown to the present generation of the navy.

What ship bearing the name of Cumberland, in the light of her past history, could ever haul down her flag? Sailing from Portsmouth, N. H., in the fall of 1860, she remained at Vera Cruz till Feb., 1861, when the rapid procession of events which led to the secession of the Gulf states, caused her recall to Hampton Roads, where she arrived in March, 1861. At this time the excitement ran high in Norfolk; many inducements were held out to the crew to desert, but few yielded to the temptation. At the suggestion of officers who afterward resigned and went into the rebellion, the Cumberland was finally moored head and stern off the navy-yard at Norfolk; ostensibly as a protection to that yard, but really that she might not interfere with the plan of blocking the channel at the mouth of the Elizabeth river with sunken vessels, which if done effectually would have left her penned like a rat in a trap.

It may all sound strange at this period, but at that time so fearful was the paternal government of hurting the feelings of the Virginians, that it permitted this attempted closing by a so-called vigilance committee of Norfolk, a body of self-constituted individuals, to go on day and night without protest or interference. The writer volunteered to take the brig Dolphin and a detachment of the Cumberland's crew to Crany island and keep the channel open at all hazards.

This was approved by Captain Marston and Commodores Pendergrass and Paulding. But the rebel officers who were at the yard advised Commodore McCauley, the senior commanding officer present, not to do it, as the youth and rashness of Lieutenant Selfridge might bring on bloodshed, which would hasten Virginia out of the Union. It was this desire to conciliate the latter, that led to the evacuation of the Norfolk yard, and not the fear of the rebel forces.

At this time, there was lying abreast of us, at the Norfolk yard, the steam frigate Merrimac, which, on account of the threatening condition of affairs, had been ordered to Philadelphia. Engineers had been detailed, a detachment of officers and sailors from the Cumberland, under Lieutenant Alexander Murray, selected to man her and to proceed as far as Hampton Roads. Steam was actually raised upon the boilers, when the naval officers of the yard (who the next day resigned) went to Commodore McCauley and persuaded him not to let the Merrimac go, as it would imply a distrust of Virginia's loyalty. The news would be telegraphed at once, they said, to Richmond, where the convention, none too loyal, was sitting to decide if Virginia should secede; its effect would be disastrous, and upon Commodore McCauley rested the responsibility of sending the state out of the Union. Influenced by this specious argument, Commodore McCauley gave the order to haul the fires, and the apportunity was lost of saving this fine frigate, that a year later was to prove the destroyer of the Cumberland.

The situation of the latter, at this time, was a singular one. A powerful vessel, securely moored in a narrow channel from which its motive power of sails was useless to extricate itself, it was left without any instructions, either to defend itself or engage in offensive operations against those who were plotting the capture of the yard, and the destruction of the Cumberland by fire-rafts.

Had there been a resolute man at the head of the navy department, the stern order would have been sent to the Cumberland, "Hold the navy-yard, and protect public property, at all hazards!" when she was first moored off Norfolk navy-yard. The yard would never have been evacuated, and its 3000 cannons, of every caliber from 32-pounders to 11-inch, which were afterwards scattered through the Confederacy, would have been saved to the Union.

Without the immense store of artillery and ammunition furnished by the Norfolk yard, many points which were rapidly fortified could never have been defended. For example, the guns on the strong fortifications at Gloucester Point, York river, which prevented the Confederate lines at Yorktown from being flanked, and caused McClellan to lose a precious month in the attempt to reduce it, were from the Norfolk yard. Those of Fort De Russey, on the far-off Red river, which gave our Mississippi fleet so much trouble, were from the same place.

Friday, April 14, brought the news of the bombardment of Fort Sumpter, and caused the wildest excitement in Norfolk. The navy-yard was closed, and the commandant sent his family away. All the officers resigned, including about one-half of the Cumberland's; but not one of the crew asked this privilege—they were all truly loyal. There remained the Cumberland and a small body of marines to defend the yard.

It should be remembered that, at this time, war had not been declared, Virginia had not seceded, and, without instructions, our commanders considered it was their duty to wait and let events take their course. This irresolution must seem difficult to understand, as we look back upon that long and disastrous war; and I well remember how all of us younger officers chafed under this do-nothing policy. But it should not be forgotten that there was a disposition at Washington to make every possible sacrifice to keep Virginia in the Union, and the knowledge of this hampered our officers and instituted a most dangerous policy.

On the following day, Saturday, hearing nothing from Washington, it was determined to scuttle the Merrimac, that is, to open her under-water valves and let her sink. I begged the captain of the Cumberland to withhold the order, for assistance might be sent, and at any time she could be sunk with a shell from our battery. But the order was given, and the Merrimac slowly sank till she grounded, with her gun-deck a little out of water.

Saturday evening, the steam sloop-of-war Pawnee, with a number of officers, and a small detachment of the Third Massachusetts, taken on board at Fortress Monroe, all under the command of Commodore Paulding, arrived from Washington. The latter was the senior officer present, and, after a consultation with Commodore McCauley and other commanders, decided to set fire to the shipping and buildings, and abandon the yard.

I believed then, and events afterwards proved it, that this was a most unfortunate decision. We should not have left without a fight; and the presence of the Pawnee, a handy and powerful steam vessel, put the situation in a very different light from the one where the Cumberland was left alone and incapable of moving. To say nothing of the Merrimac and the immense quantity of cannon and munitions of war, the use of the workshops acquired by the Confederates was of the greatest assistance to the rebellion in its early stages. Three line-of-battle ships, Pennsylvania, Columbus and Delaware; four frigates, the Merrimac, Brandywine, Columbia and Raritan; one sloop-of-war, the Germantown, and the brig-of-war Dolphin, with the immense ship-houses, were fired. Thus was destroyed, at one blow, one-fourth of the American navy. It was a splendid, but melancholy spectacle, and in the lurid glare, which turned night into day, the Cumberland slipped her moorings, and, in tow of the Pawnee, left Norfolk.

Had the Merrimac not been previously sunk, she would have been totally destroyed with the rest. But resting on the bottom with her gun-deck above water, only the upper works were burned. After taking possession of the yard it was not a difficult matter for the Confederates to close the valves, pump the ship out, and float her into the dry-dock, from which she emerged several months after, as an iron-clad called the "Virginia."

At daylight, the Cumberland was off Sewall's Point, at the mouth of the Elizabeth river, where for two weeks a body of disaffected and irresponsible people had been allowed to seize and sink three light ships at anchor in Norfolk harbor and several schooners belonging to Northern owners; and all this in the face of the U. S. authorities. This must seem strange reading at present, but it is an example of the weak and vacillating policy of the government in the early days of the war to win back states to their allegiance, which had but one idea, and that the severance of all relations with the hated North.

But to return to the Cumberland. With the assistance of the Pawnee, Keystone State, and the tug Yankee, she was finally forced over the obstructions, and at night fall anchored off Fortress Monroe. Here she remained as a guard-ship till the summer, when she was sent to Boston to be docked, and damages from grinding on the wrecks off Sewall's Point made good. After completing these repairs, and filling the vacancies in her crew, she sailed for Hampton Roads and was employed in the blockade of Hatteras inlet until she took part with the steam frigates Minnesota, Wabash and Susquehanna in the bombardment and capture of the Hatteras forts. An example of the splendid crew with which the Cumberland was manned took place on the second day of this affair. The appearance of the weather on the previous evening had caused the ship to seek an offing and in the morning she stood in, and finding the three steam frigates at anchor and engaged, the Cumberland stood down for the head of the line, and luffing ahead of the leading ship, the Susquehanna, shortened and furled sails with one watch while the other manned the guns and as the anchor was let go, opened with the whole battery.

Old officers who saw the manoeuvre, have often spoken of the beauty of the ship as she stood in under all sail, and the magnificent manner with which she went into action, the last American frigate to go into battle under sail.

But the era of steam had arrived, sailing ships were useless on a blockade, and the Cumberland was ordered to Hampton Roads.

At this time two steamers known as the Jamestown and Yorktown, belonging to the Old Dominion Steamship Co., had been seized at Richmond, armed as privateers and threatened to run out. To prevent their escape the Cumberland was sent in November, 1861, to the mouth of the James river, off Newport News. Here she was joined by the Congress, a sailing frigate of a little more tonnage, but with a greatly inferior battery of 32-pounders. The winter of 1861-62 was occupied on the Cumberland in constant drill to meet every imaginable contingency in a combat with the Merrimac, the news of whose preparation reached us from time to time. In fact, rumors of her expected appearance came so often, that at last it became a standing joke with the ship's company. The winter was a severe one, no fires were allowed, and our enforced idleness became extremely irksome, and we all looked forward to a relief in the spring, and a chance for active operations. All the winter one watch slept at the guns, the ship nightly cleared for action, was ready for any emergency. In view of a possible encounter with the Merrimac, solidshot had been supplied for the 9-inch guns, the normal charge increased from ten to thirteen pounds of powder, and the guns provided with double breechings, to stand the increased recoil.

Commodore Pendergrass had hauled down his flag after the evacuation of Norfolk. Captain John Marston had been transferred to the Roanoke after the bombardment of Hatteras. Captain John Livingston succeeded him, to be in turn relieved by Captain William Radford, who commanded the ship at the date of the action, but was temporarily absent on court martial duty at Hampton Roads.

The officers of the Cumberland on the 8th of March, 1862, in the fight with the Merrimac were, Lieut. Geo. N. Morris, executive officer; Lieut. Thos. O. Selfridge, Jr.; master, W. S. Stuyvesant; acting master, W. W. Kennison; acting master, W. P. Randall; 2d lieut., marines, Chas. Heywood; surgeon, Chas. Martin; asst. surgeon, Edward Kersiner; paymaster, Cramer Burt (absent); chaplain, John T. Lenhart (killed); acting master's mates, John Harrington (killed); Chas. O'Neil, H. Tyson, H.Wyman; boatswain, Edward Bell; gunner, Eugene Mack; carpenter, W. M. Leighton; sailmaker, David Bruce; paymaster's clerk, Hugh Knott; pilot, Lewis Smith.

Lieutenant Morris as executive officer, in the absence of Captain Radford, was in command on the gun-deck. Lieutenant Selfridge commanded the forward division of five 9-inch guns; Master Stuyvesant the after division of four 9-inch, and the two extreme after guns were manned by marines. The guns crews consisted of sixteen men and a powder boy. The forward 10-inch pivot was in charge of Acting Master Kennison, the after in charge of Acting Master Randall. Sailmaker Bruce commanded the powder division assisted by gunner Mack.

When the Norfolk yard was evacuated the Confederates raised the Merrimac, placed her in the dry-dock, and cut down the upper works even with the berth-deck. She was of the same class as the Wabash, (at present receiving ship at the Boston navy-yard), some 4500 tons burden, about 300 feet long, 52 feet beam, and drew about 24 feet. A low casemate was built upon her with sides receding at an angle of about forty-five degrees, and extending about 200 feet of her length. This casemate was armored with four inches of iron, laid on in two layers diagonal to each other. Each slab was four inches wide and two inches thick, the whole backed by two feet of oak. Her sides were armored, and also the deck forward and abaft the casemate. She had a freeboard of not more than a foot when she engaged the Cumberland. Her armament consisted of on e 7-inch rifle in the bows, a similar gun aft; two 6-inch rifles and six 9-inch guns in the broadside. She was fitted with a ram made of cast iron, which projected three feet from the stem, and at about six feet under water.

The Fight. —Saturday the 8th of March, 1862, was a beautiful spring day, bright and clear. The Cumberland was lying at single anchor, with her sails loosed to dry, when at a half hour after noon, the writer who was the officer of the deck reported that the Merrimac had just hove in sight a long distance off in the direction of Norfolk. Owing to the mirage her movements were much obscured, and her progress was so slow that it seemed doubtful at first if she was really coming out.

But as the low hull came in view abreast of Crany island light heading for the mouth of the Elizabeth river, all surmises were dispelled. All hands were called, the sails quickly furled, and the quick beat to ''quarters'' aroused everyone, and told that the hour which had been so long looked forward to had come. At that moment the Cumberland was a splendid type of the frigate of the old times, with her towering masts, long yards, and neat man-of-war appearance.

But her crew as they stood at their guns for the last time, cool, grim, silent and determined seamen, confident in their discipline, proud of their ship, were a model crew. A crew that has never been excelled and perhaps rarely equalled. It was a crew, that, knowing no surrender, could they have had a motive power other than sails, would have whipped the Merrimac by the sheer force of their battery and their determination to conquer. On account of the contour of the land at the mouth of the James river, the Merrimac passed out of sight from the deck of the Cumberland for over one hour, and it seemed doubtful whether the first attack would be upon the squadron at Hampton Roads or against the Congress and Cumberland. The delay was so great that many feared the opportunity would not be given to try their heavy guns; for what was known at that time of the relative merits of iron-clads and wooden ships? And great confidence was felt by the Cumberland in her trained crew and solid shot of eighty pound weight.

But at 2: 30 P.M. the Merrimac hove in sight, heading directly for the Congress, which was riding to the last of the flood. The Cumberland, above and a little inshore, had begun to swing and lay almost across the river, her bows outwards.

As the Merrimac passed the Congress the latter opened with her whole broadside which rattled from the sides like hail upon a roof. This effect caused no surprise on the Cumberland because her guns were so much lighter than ours, being mostly thirty-two pounders.

The Merrimac moved slowly across the bows of the Cumberland and manoeuvred for position to ram. Three times were the gun divisions sent from one battery to the other, till finally she came sufficiently in sight upon the starboard bow to train the forward guns, and fire was at once opened with them and the bow 10-inch pivot.

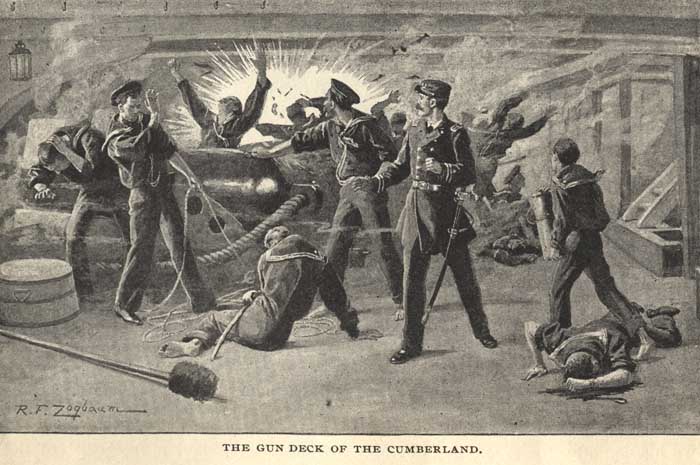

The Merrimac replied with her 7-inch rifle and broadside guns, sometimes aiming the latter at the small fort on shore. Her first shot passed through the star-board hammock netting, killing and wounding nine marines, and their commander, Lieutenant Heywood, who was amongst them, was knocked down, but uninjured. The groans of these men, the first to fall, as they were carried below, was something new to those crews as they stood at their guns, and an introduction to a scene of carnage unparalleled in war.

Three soldiers from the shore who had come off to visit the ship were unable to return, and asked permission to join the gun crews. Two of them were killed, and one, McNamara, escaped.

The Merrimac lay about three hundred yards on the starboard bow, raking the Cumberland at every shot, while only the forward and the pivot guns of the first division by extreme train could be brought to bear on her.

Number one gun of this division was fired but once. The second shell from the murderous 7-inch rifle burst among the crew, as they were running the gun out, destroying literally the whole crew, except the powder man, and the gun remained disabled for the rest of the action. The captain of this gun, a splendid seaman, named Kirker, rated commodore's coxswain, had both arms taken off at the shoulder, as he was holding his handspike and guiding the gun. He passed me as he was carried below, but not a groan escaped from him.

The spring from the starboard quarter was now manned on the spar-deck, and an attempt made to spring the broadside to bear; but this was ineffectual, for, on account of the slack tide and no wind, the spring lay fore and aft and useless. Events followed too fast to record them. The dead were thrown over the other side of the deck, the wounded carried below; no one flinched, but went on loading and firing, taking the place of some comrade, killed or wounded, as they had been told to do. But the carnage was something awful; great splinters, torn from the side, wounded more men than the shell. Every first and second captain of the first division was killed or wounded, and the writer, with a box of cannon primers in his pocket, went from gun to gun, firing them as fast as the decimated crews could load them.

But to return to the Merrimac. She kept up the destructive fire for some fifteen minutes, when she headed for the Cumberland, striking her upon the starboard bow, her ram penetrating the side under the berth-deck. She could not extricate herself, and, as the Cumberland commenced to sink, she bore the Merrimac down with her, until the water was over the forward deck. Had the officer forward on the spar-deck of the Cumberland had the presence of mind to let go the starboard anchor, it would have fallen on the Merrimac's deck and she would have been carried down in the iron embrace of the Cumberland. But the opportunity was lost; the weight upon the ram broke it off in the Cumberland's side, and the Merrimac swung round, broadside to the Cumberland. Whether the Merrimac was demoralized by this narrow escape, or her engines caught on the center, or for some other cause, she lay for some moments without moving. This was the Cumberland's opportunity, the first she had had, for the Merrimac had all along maintained a sneaking position on the bow, almost out of gunshot; and three solid broadsides, at a distance of not more than one hundred yards were poured into her, that, Confederate officers have told me, made the Merrimac fairly reel. Cheer upon cheer went up from the Cumberland, followed with rage and despair, as she slowly moved away, with the nozzles of two of her broadside 9-inch guns shot away. Seeing that our shot made so little impression, the gun captains were ordered to fire only at the ports.

The Merrimac, at this time, hailed the Cumberland, and asked if she would surrender. The reply went back: "Never! We will sink with our colors flying!"

It is a question whether Captain Buchanan was wounded at this time, by one of the marines on the spar-deck, or later on. Lieutenant Heywood, who, at Mobile, had charge of him after the fight with the Tennessee, writes me that Captain Buchanan told him he was wounded by a shot from the Cumberland, as he incautiously exposed himself in the pilothouse of the Merrimac; but I have seen Confederate accounts which place this event later on.

The water was rising rapidly, the Cumberland going down by the bows. The forward magazine was flooded, but the powder tanks, which supplied the forward divisions, had been whipped out, carried aft, and the supply of powder kept up. As the water made its appearance on the berth-deck, which, by this time, was filled with the badly wounded, heart-rending cries could be heard above the din of the combat, from the poor fellows, as they realized that they were helpless to escape a slow death as the water rose over them.

The Merrimac again took a position upon the starboard bow of the doomed Cumberland, and opened her fire. The first cutter was sent, with a hawser, from the port quarter to a schooner near by, and an effort made to spring our broadside to bear; but the Cumberland was becoming so waterlogged that she could not be moved.

The writer gathered the remains of the first division—some thirty men—and took them forward, to transport number one gun to the bridle-port, in a position that it could bear upon the Merrimac. The tackles were scarcely hooked, when a shell, passing through the starboard bow, burst among them, killing and maiming the greater number. It was about this time that Master-mate Harrington had his head shot off, and fell, a corpse, at my feet, in the act of receiving an order to slip the cable. There was no one left in the first division; not a gun's crew could be mustered from the brave fellows who went into action, three-quarters of an hour before, so confident in their ship. No men ever stood at their guns better than the first gun-deck division of the Cumberland. They had literally disappeared—died at their posts.

The appearance of the gun-deck forward, at this time, was something never to be forgotten—the deck covered with the dead and wounded, slippery with blood; the large galley demolished, and its scattered contents added to the general destruction; some guns run in as they had last been fired, many of them bespattered with blood; rammers and sponges, broken and powder-blacked, lay in every direction.

In the meanwhile, the water had been rapidly gaining, in spite of the efforts of the after-division, which had been sent to the pumps. At this time, the Merrimac again rammed the Cumberland, striking her abaft the fore-channels, but doing no special damage. Why she did so, I have never understood, unless to a final coup de grace, for she must have seen that the Cumberland was rapidly sinking.

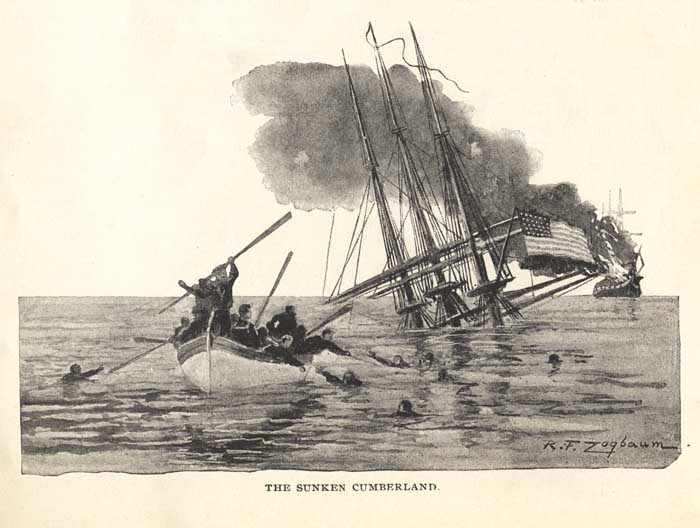

If there had been any men left, there was no longer any powder to serve the guns of the first division. The writer went aft, and, as he did so, the ship lurched forward, and the water poured into the bridle-ports. The ship was sinking; no time was to be lost, and the order was passed for every man to "look out for himself"—an order never given until the last extremity. The survivors rushed from the berth-decks and gun-decks, crowding up the after-ladders; some ran along the spar-deck and jumped into the launch, moored astern; others climbed the rigging, and others saved themselves on gratings and material from the deck. Fortunately, all the boats were lowered before the action commenced, and two of the largest were uninjured.

In this moment of dire confusion with the waters closing over the doomed ship, the last gun was fired, sounding the death knell, generally believed to have been gun number seven, and fired by Matthew C. Tierney, coxswain, who was mortally wounded and perished in the ship.

The writer was one of the last to leave the main deck, the water upon which was up to the main hatch. The ship had a heavy list to port, the ladders were almost perpendicular, and as he turned to the ward-room hatch ladder he found it blocked by our fat drummer Joselyn, struggling up with his drum, and who was afterward picked up using it as a buoy. He then threw off his coat, and sword, and squeezing through the port hole on the port side, jumped into the water, and seeing the launch astern swam to her and was picked up almost exhausted.

As has been stated the ship went down bow first, with the stern high in the air. There was about one hundred men in the launch, among them Lieutenant Morris and Master Stuyvesant. It was with difficulty that the boat was shoved clear, as with one plunge the Cumberland settled beneath the surface. Her flag could almost be touched as the boat moved away, but it was left to wave over the glorious dead who had defended it with their lives.

The crew of the Cumberland on the day of the engagement numbered 299 blue jackets and thirty-three marines. Of this number eighty were killed or drowned, and some thirty wounded saved, or a total of killed and wounded of over thirty-three per cent. I doubt if any battle of the war, ashore or afloat, can exhibit so large a proportion of dead to the number engaged, and it shows the desperate character of the fighting. The brunt of the fight fell upon the first division, commanded by the writer, and out of a total of eighty-five more than half were killed.

It is not easy to estimate the damage done to the Merrimac. Her smoke-stack was so perforated with shot-holes, as to fill the gun-deck with smoke, and seriously decreased the draft of her boilers. The flag-staff was shot away. Many of the plates on the casemate were loosened. The muzzles of two of her guns were shot away, and of the crew two were killed and numbers wounded, amonst the latter her captain, Buchanan, who was a great loss to the Confederacy. Her ram was wrenched off in the Cumberland's side, causing the Merrimac to spring a leak, and the wounding of her commander was a serous misfortune to them.

Thus perished the Cumberland. No vessel ever went into a fight against greater odds, so great that but one result was possible, and yet fought to the bitter end, until the waters closed over her last gun. The Merrimac was more than double the size of the Cumberland, with armor four inches thick to oppose the wooden sides of the latter, and enable to take any position at will, while the latter was chained to the bottom and helpless to move. There would have been no dishonor in surrendering to such odds, and yet what would have been the result? The Merrimac fresh from the surrender of the Cumberland, would have destroyed the fine steam frigate Minnesota that had grounded while going to the assistance of the Cumberland, would have captured the remaining naval force at Hampton Roads, consisting of the frigate Roanoke, which had lost her screw, and the sailing frigate St. Lawrence, and when the Monitor arrived late Saturday night she would have found herself alone. What would have been the fate of the Monitor if the latter had not lost her spur in the Cumberland's side?

And yet the government bestowed neither promotion or medals upon the officers and crew of the Cumberland, and only some years after made an appropriation giving a month's pay to the survivors for the loss of their effects! History can point to no greater sacrifice for the honor of the flag than that made by the crew of the Cumberland. Without hope of assistance, against fearful odds, they fought to the end and their ship was their tomb. Let their memory be kept green in the hearts of their countrymen, and if their example stimulates the youths of coming generations to be true to their country and their flag, it cannot be said they died in vain.

No braver vessel ever flung her pennon to the breeze,

No bark e'er died a death so grand;

Her flag the gamest of the game

Sank proudly with her, not in shame,

But in its ancient glory—

The memory of its parting glean

Will never fade while poets dream;

The echo of her dying gun

Will last till man his race has run—

Then live in angels' history.

Captain Thomas O. Selfridge was born in Charlestown, Massachusetts, in 1837, and, when only seventeen years of age, graduated from the United States naval academy, at the head of his class. He was, therefore, only twenty-five years of age when he saw this tremendously active service as second lieutenant of the unfortunate Cumberland. When the Merrimac destroyed his ship, Lieutenant Selfridge was detailed to command the Monitor; but other causes led to his transference as flag-lieutenant of the North Atlantic blockading squadron. He was in all the severe fighting about Vicksburg and Red river and Fort Fisher, and was continually promoted, attaining the rank of commander in 1869. Nor did his stirring life end with the war, for he has since commanded several exploring expeditions in South America. He found time, too, to invent a device for protecting a ship, by suspending torpedoes to a net, which would destroy the attacking torpedo.

THE END.