NORFOLK NAVY YARD

Marcus W. Robbins, Historian & Archivist

Copyright. All rights reserved.BATTLE OF THE HAMPTON ROADS IRONCLADS

Index this Page:

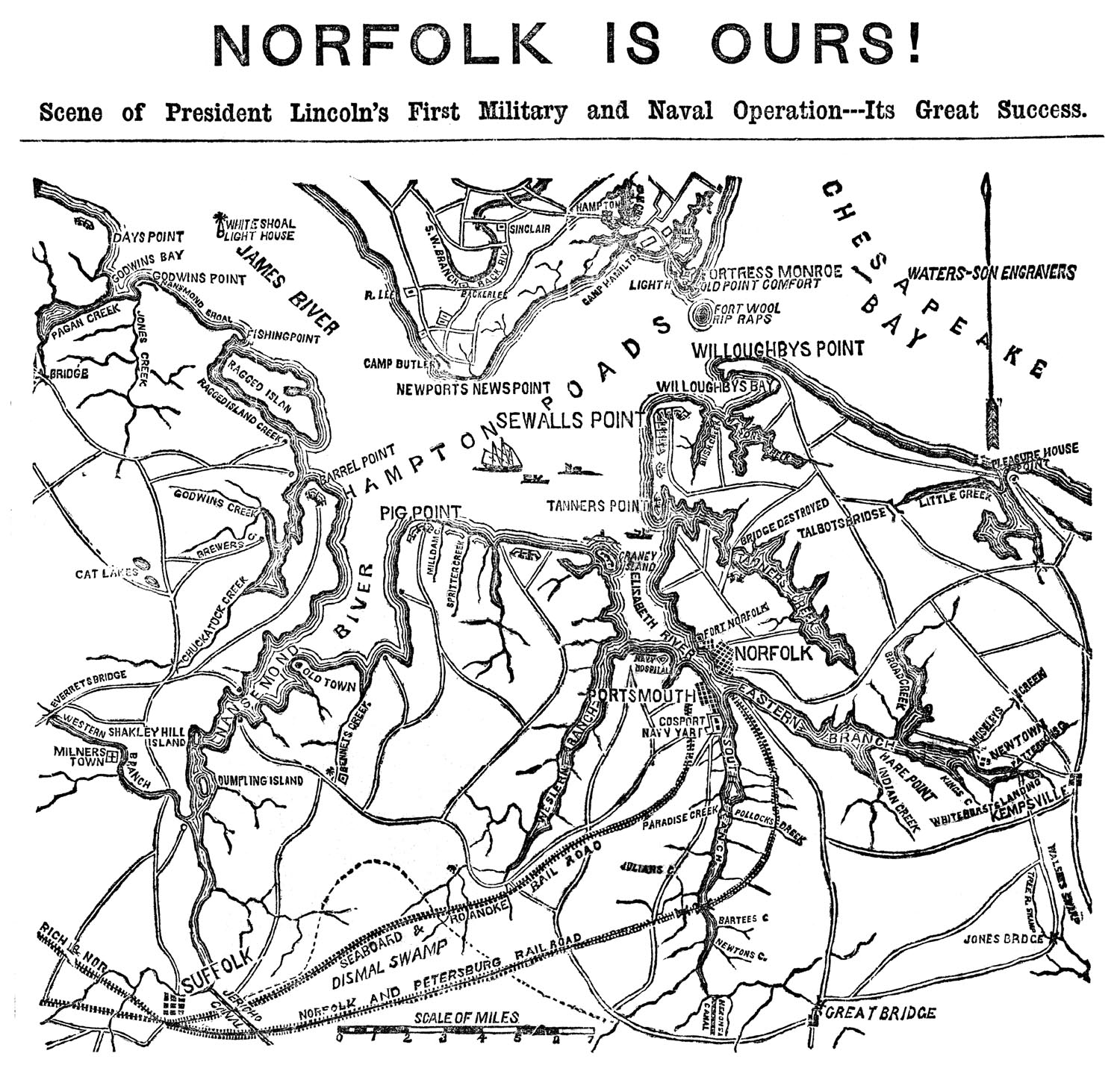

NEW YORK HERALD:

May 12, 1862: Norfolk is Ours.

May 13, 1862: The Capture of Norfolk.

WASHINGTON, May 11, 1862.

The following was received at the War Department this morning:—

SECRETARY STANTON'S BULLETIN.

FORTRESS MONROE, May 10, 1862, Twelve o'clock, midnight.

Norfolk is ours, and also Portsmouth and the Navy Yard.

General Wool, having completed the landing of his forces at Willoughby Point about nine o'clock this morning, commenced his march on Norfolk with 5,000 men.

Secretary Chase accompanied the General.

About five miles from the landing place a rebel battery was found on the opposite side of the bridge over Tanner's creek, and, after a few discharges upon two companies of infantry that were in the advance, the rebels burned the bridge.

This compelled our forces to march around five miles further.

At five o'clock in the afternoon our forces were within a short distance of Norfolk, and were met by a delegation of citizens.

The city was formally surrendered.

Our troops were marched in and now have possession.

General Viele is in command as Military Governor.

The city and Navy Yard were not burned. The fires which have been seen for some hours proved woods on fire.

General Wool, with Secretary Chase, returned about eleven o'clock to-night.

General Huger withdrew his force without a battle.

The Merrimac is still off Sewall's Point.

Commander Rogers' expedition was heard from this afternoon, ascending the James river.

Reports from General McClellan are favorable.

EDWIN M. STANTON.

* * * * * *

THE PRESS DESPATCHBALTIMORE, May 11, 1862.

The Old Point boat has arrived.

Our troops crossed to the Virginia shore during Friday night, while the Rip Raps shelled the rebel works at Sewall's Point.

A landing was effected at Willoughby Point at a spot selected the previous day by President Lincoln himself, who was among the first who stepped ashore.

At last advices General Max Weber was within three miles of Norfolk.

The Merrimac remained stationary all day off Craney Island.

THE MERRIMAC DESTROYED.

To Hon. J. H. WATSON, Assistant Secretary of War:—

The Merrimac was blown up by the rebels at two minutes before five o'clock this morning. She was set fire to about three o'clock.

The explosion took place at the time stated. It is stated to have been a grand sight by those who saw it.

The Monitor, E. A. Stevens (Naugatuck) and the gunboats have gone up towards Norfolk.

THE PRELIMINARIES OF THE CAPTURE.

FORTRESS MONROE CORRESPONDENCE.

FORTRESS MONROE, May 7, 1862.

This morning, about six o'clock, a strange steamer entered the harbor. After steaming around the Vanderbilt, hailed her, stating that the President, with Secretaries Stanton and Chase, was on board, and would visit the Vanderbilt. After a few moments the President came alongside and was received at the gangway by Captain Lefevre. When the President and his party had been shown all through the ship by Captain Lefevre, they expressed themselves well satisfied with the preparations made on board to destroy the Merrimac. It is not permitted at present to make known what these preparations are, but the President felt confident that the Vanderbilt alone was able to destroy the Merrimac. The President, Secretaries Stanton and Chase, expressed a hope that some future day they would be able to take a voyage to Europe and back in the Vanderbilt. It will be recollected at the commencement of the war that Commodore Vanderbilt offered his entire fleet of steamers to the government at the government's own valuation, and also his best steamer, the Vanderbilt, as a free gift to capture privateers on our coast; but Secretary Welles did not deem it advisable to receive this offer, from the fact that the outside agents of the Secretary could not receive the two and a half per cent, or any amount of money, in the shape of a bribe from Commodore Vanderbilt. It was with the greatest difficulty that he could get a charter for his ships, on account of not paying any bribe money to the chartering agents; but after the first appearance of the Merrimac in Hampton Roads, Commodore Vanderbilt, seeing the threatened danger, repaired at once to Washington and had a private interview with President Lincoln, which resulted in the Commodore again presenting the Vanderbilt as a free gift to the government, which was accepted by the President personally. The Vanderbilt is now under the control of the President and Secretary of War, Commodore Vanderbilt declining all interviews or correspondence on the subject with the Secretary of the Navy. The Navy Department has not now any control of his ship; but Commodore Vanderbilt has placed his well know and popular commander, Captain P. R. Lefevre, in full charge, and the War Department has allowed Captain L. to act according to his own discretion. All Captain Lefevre hopes for is that the Merrimac will come out, so that he can sink her before he returns to New York. Captain L. has been in command of the V. for a number of years, in the European trade, for a number of years, and all anxiously expressed their desire that the Merrimac will make her appearance in the Roads, so that they may have the pleasure of participating in the honors of sinking her. The naval and military officers at this place seem to have more confidence in the Vanderbilt for this important undertaking than any other ship of the fleet, on account of her commander having discretionary power.

The following is the list of officers attached to the Vanderbilt:—

Captain—P. E. Lefevre.

Chief Officer—T. Kidd.

Second Officer—D. Gay.

Chief Engineer—J. Germain.

First Assistant—W. Golden.

Second Assistant—H. Miles.

Chief Steward—J. McHenry.

Boatswain—D. Hines.

Government Pilot—O. Cavallier.

Also, a crew of 100 men.* * * * * *

FORTRESS MONROE, May 8, 1862.

This morning the rebel steamer Yorktown started up the James river to join her consort, the Jamestown. A little while afterwards the steamtug J. A. White came down the river and delivered herself up to our forces at Newport's News, when she was immediately despatched to the fort. Pert of the intelligence she brought was, that since the enemy's retreat from Yorktown a panic has taken possession of the inhabitants of Norfolk, and that both troops and citizens are now evaluating the place. Commodore Goldsborough immediately despatched the Galena, Octorara and another gunboat up the James river in pursuit of the Yorktown. In about two hours heavy cannonading was heard in the direction of Day's Point, some fifteen miles from Newport's News, where it was supposed that our vessels were engaged with the enemy's batteries and fleet. It is now none o'clock. Nothing has been heard from them since. The Commodore then signalized the fleet to prepare for action, and despatched tugs to the "rams" also to be prepared, as he was about to engage Sewall's Point batteries, in hopes to draw the Merrimac down from her hole. The Seminole immediately got under way for the Point, followed by the San Jacinto, Susquehanna and Wachussett, and took a position abreast of the Point, when they opened fire, which was not replied to until some five or six shots were fired. When the ball was fairly opened the Monitor started and took a position in advance of our fleet, between the Rip Raps and Sewall's Point. In the meantime General Wool ordered a body of troops—a portion of General Max Weber's division—to hold themselves in readiness to embark at a moment's notice, as it was the intention to land them and take possession of the works as soon as the navy had prepared the way. A heavy black column of smoke was observed to arise from Sewall's Point. At first it was supposed the enemy had fired their works, and were retreating, as the battery had not fired for some little time previous; but our fond hopes were soon dispelled when a jet of white smoke arose and a shell was sent in the direction of the Monitor. About four o'clock the Merrimac made her appearance, when our vessels commenced to fall back from their positions, in hopes that she would follow them up; but she thought "discretion was the better part of valor," and did not follow. The Rip Raps opened upon her until she put back towards Craney Island. Some of the shots went clear beyond her—on hit her. During the engagement the enemy's flag was shot away, when one of their men want to take it up, and a shell sent him to his long home. President Lincoln, with Secretaries Stanton and Chase, were on the Rip Raps during the engagement. Thus ended this day's work.

Tonight it is the intention to land a body of troops at Lind Haven Bay, and tomorrow the curtain will again rise, when, it is earnestly wished and hoped, it will not descend until Norfolk is in our possession, and that pest, the Merrimac, destroyed; for it will be a disgrace to the nation if she is not. Here we have the representatives of three European Powers in these Roads in the presence of the English, French and Norwegian men-of-war. It is a burning shame to have them look upon this fine fleet, and see one solitary vessel keep them all at bay. The Monitor is her equal, if not her superior, so it is represented; if so, she having such a fleet to assist her, when is it that the Merrimac is such a terror, and why has she not been destroyed before, so that part of the vessels can be relieved from this point, and sent to other places that stand in need of their assistance—to Charleston, for instance?

* * * * * *

FORTRESS MONROE, May 9, 1862.

After the splendid (!) cannonade or bombardment of the rebel works at Sewall's Point yesterday, in which nobody was killed and nobody was wounded, our vessels returned to their respective anchorages unscathed. The appearance of the rebel craft Merrimac, as she steamed down the Elizabeth river, hastened, and in fact terminated, the affair. This morning I learn that Flag Officer Goldsborough gave orders to the vessels of the fleet to engage the rebel batteries at long range. Had a contrary system been pursued there is no doubt but that our fleet could have brought the rebels to surrendering terms. The officers on our fleet, than whom there are no braver in the service, felt much chagrined at not being permitted to close in on the rebels and capture their guns. Flag Officer Goldsborough took no part in the engagement, but remained quietly enjoying the scene on board his ship—the Minnesota—four miles from the scene of action. His orders were conveyed from time to time, as the engagement proceeded, by means of small steam propellers, of which he employed half a dozen or more.

The Merrimac, after she came out as far into Hampton Roads as the prudence of her traitor officers would permit, looked at the Monitor as a lion watches its prey, and then steamed back to the north end of Craney Island, where she is now keeping watch and ward over Norfolk and its vicinity.

At ten o'clock this forenoon the Flag Officer sent orders to the Monitor to slip anchor and make a reconnaissance in the direction of Sewall's Point, and feel the enemy's works, and to ascertain, if possible, whether or not the rebels had evacuated them, as had been reported by the refugees who escaped from Norfolk the day previous. In a few minutes the Monitor was under full steam and heading to execute the orders of the Flag Officer. The day was exceedingly fine, the sky an azure blue and clear, and the waters in the Roads of glassy smoothness. The Monitor glided from her moorings with ease, and as she made the various turns in the tortuous channel leading to the Elizabeth river she answered her helm with apparent ease. There was another object in view by moving the Monitor in the direction of Elizabeth river. As I mentioned in my letter of yesterday, the battery Galena and the gunboats Port Royal, commanded by the gallant Lieutenant Morris, of Cumberland fame, and the Aroostook, which were sent up the James River on a reconnaissance, were expected to return at noon to-day. From the menacing position of the Merrimac it was thought she might essay to attack our vessels as they returned to Hampton Roads. To obviate this the Monitor took a position in the channel, to frustrate this apparent design. At twenty-five minutes past ten the Merrimac was observed steaming slowly down the river towards the Monitor, but she had proceeded but a few lengths when she apparently brought up on a sand bar, as it was but "half ebb tide" at the time. As soon as she stopped the heavy clouds of steam issuing from her steam pipe indicated that she had a good head or force of steam on. About this time heavy cannonading was heard, coming from the direction of James river; it was supposed to have been from the Galena and her consorts, engaging the rebel batteries at Day's Point and vicinity, which, I am informed by Assistant Secretary of War Tucker, they passed successfully yesterday, under a terrific cannonade from the enemy.

At ten minutes past eleven o'clock A. M. the Monitor had attained a position about four miles from her permanent anchorage, equi-distant from the fortress and Craney Island and where the Merrimac lay. She steamed slowly, as if to challenge her much vaunted antagonist to combat. The rebel craft did not seem inclined to accept the invitation, but sought more congenial grounds, under the cover of the rebel batteries at Sewall's Point and Craney Island. The Monitor then turned her prow towards Sewall's Point, and steamed up to within a mile of the rebel works, where a good inspection of them was had. Several guns were seen in position; the rebel flag was flaunting defiantly to the breeze, yet but few rebel soldiers were seen. At five minutes of eleven o'clock the Union battery at Fort Wool, Rip Raps, opened fire on Sewall's Point. The very first shell went directly into the rebel camp, its arrival being denoted by a loud report and the rising of a dense column of smoke from woods in the vicinity. The first shot was but the precursor of many others, and for upwards of two hours there were fifty shells thrown at the rebels, with an accuracy of range, aim and effectiveness not to be surpassed. At one time the woods at Sewall's Point were fired in several places, but the wet and sappy nature of the trees prevented is spreading to any great extent. Of course I could not learn to what extent the rebels suffered by this bombardment, if at all; but it seems to me the sharp reports of our bursting shells must have been unpleasant to their auricular senses.

At six minutes past eleven A. M. the Monitor attained a position within three-fourths of a mile of the rebel battery; from my point of observation I noticed the firing of the gun by the flash and rapid movement of a dense column of white smoke, expanding as it rarified out into thin air; a few seconds elapsed, and the report reached my ears, and almost simultaneously the splashes in the water, throwing up a thin column of spray, indicated the direction of the ball as it ricocheted into the rebel works. The aim of the eleven-inch shell struck, which was in about ten seconds after it left the muzzle of the gun, it burst with a loud report. At twenty minutes past eleven o'clock the signal officer in the fort reported the Merrimac moving down the Elizabeth river, having, it was thought, extricated herself from her position on the sandbar, on which she ran in the early part of the forenoon. The alarm gun in the esplanade of the fortress was fired, the gun on the ramparts were manned by our well-disciplined cannoniers, and everything was got in readiness for action.

At twenty-seven minutes past eleven o'clock the Monitor fired a second shot at the rebel battery. The report of the gun was like a clap of thunder, and the explosion of the missile in the enemy's ranks must have occasioned some mischief. At half-past eleven o'clock the Merrimac was observed under way again down the river, but after moving a short distance brought up again suddenly on a sandbar, where she remained until four P. M.

Her side swung around, by the action of the tide, so as to present a broadside to the face of the channel. Her armor was covered with a thick coat of grease and black lead, which, as the sun reflected on it, gave it a brilliant glassy appearance. The Monitor continued to steam about the Roads, between this point and Newport's News, exhibiting her sailing qualities with much satisfaction. At five P. M. she returned to her anchorage.

President Lincoln and Secretaries Chase and Stanton still remain her; the business of the government pro tempore appears to have been transferred here. The President has himself, by his personal orders, stirred up the Flag Officer of the naval fleet, who has a reputation for masterly inactivity. I have learned of measure that the President and his secretaries have now under consideration, which will be put into practical operation ere the lapse of many days. The President and General Wool, and Captain J. Millward, Jr., made an important and dangerous reconnaissance to-day in the revenue steamer Miami. The measure was instituted by the President, and carried out under his personal dispassionate, honest statesman, but a naval and military commander of no mean pretensions. I shall speak further of the nature of this reconnaissance at the proper time. The President subsequently proceeded on a brief excursion in the Roads, visiting the naval vessels and communicating orders.

For the past week volunteer surgeons and nurses have arrived in great numbers. Their services are available at a most opportune time, when the wounded are reaching this point from the Army of the Potomac. There are also numerous wealthy gentlemen and philanthropists, who, from a sense of their duty to the country, now visit this military department to aid, personally and pecuniarily, the sick and destitute soldiers. Among these gentlemen, whose liberal acts entitle them to honorable mention, is Dr. Clement B. Barclay, of Philadelphia. He is indefatigable in measures for the relief and comfort of the sick. A few days ago, while going his rounds in the hospital, he was suddenly accosted by a friend, who said, "Why, sir, I am glad to see you. I understood that you were looking after the sick and wounded of Philadelphia." Mr. B. replied, after passing the time of day, "I am a citizen of Pennsylvania, but I came here to help the soldiers of the whole Union; I recognize no State lines in the present crisis"—a sentiment well and patriotically said.

The fact that the citizens of Norfolk did not rush with very great eagerness to the support of Jeff. Davis, would appear to be proven from the following:—

[Correspondence of the Petersburg Express, May 2.]

NORFOLK, May 1, 1862.

Another importation of unarmed militia reached here yesterday, and were seen making their way through the streets. A "substitute" was purchased here yesterday for $1,200.

* * * * * *

FORTRESS MONROE, May 9—Evening.

Old Point this evening presents a most stirring spectacle. About a dozen steam transports are loading troops. They will land on the shore opposite the Rip Raps, and march direct on Norfolk.

At the time I commence writing (nine P. M.), the moon shines so brightly that I am sitting in the open air, in an elevated position, writing by moonlight. The transports are gathering in the stream. They have on board artillery, cavalry, infantry, and will soon be prepared to start.

The Rip Raps are pouring shot and shell into Sewall's Point, and a bright light in the direction of Norfolk leads to the supposition that the work of destruction has commenced.

President Lincoln, as Commander-in-Chief of the Army and Navy, is superintending the expedition himself. About six o'clock he went across to the place selected for the landing, which is about a mile below the Rip Raps. It is said he was the first to step on shore, and, after examining for himself the facilities for landing, returned to the Point, where he was received with enthusiastic cheering by the troops who were embarking.

It is evident that the finale of the rebellion, as far as Norfolk is concerned, is rapidly approaching. The general expectation is that the troops now embarking will have possession of the city before to-morrow night.

TEN P. M.

The expedition has not yet started, the delay being caused by the time required for staking the horses and cannon on the Adelaide. The batteries at the Rip Raps have stopped throwing shells, and all is quiet. The scene in the roads, of the transports steaming about, is most beautiful, presenting a panoramic view seldom witnessed.

ELEVEN P. M.

The vessels have not yet sailed. The Merrimac exhibits a bright light. It is said the Seminole will go up the James river in the course of the night.

* * * * * *

WILLOUGHBY POINT, May 10, 1862.

The troops left during the night, and at daylight could be seen landing at Willoughby Point, a short distance from the Rip Raps.

Through the influence of Secretary Stanton I obtained this morning a permit to accompany General Wool and General Mansfield and staffs to Willoughby Point, on board the steamer Kansas, and here I am on "sacred soil," within eight miles of Norfolk. The point at which we landed is known as Point Pleasant, one of the favorite drives from Norfolk.

The first regiment landed was the Twentieth New York, known as Max Weber's regiment, which pushed on immediately, under command of Gen. Weber, and were, at eight A. M., picketed within five miles of Norfolk. The First Delaware, Colonel Andrews, was pushed forward at nine o'clock, accompanied by Generals Manfield and Viele and staff. They were soon followed by the Sixteenth Massachusetts, Colonel Wyman.

The balance of the expedition consists of the Tenth New York, Colonel Bendix; the Forty-eighth Pennsylvania Colonel Bailey; the Ninety-ninth New York (coast guard); Major Dodge's battalion of mounted rifles, and last Follett's Company D, of Fourth regular artillery. Gen. Wool and staff remained to superintend the landing of the balance of the force, all of whom were landed and off before noon.

The President, accompanied by Secretary Stanton, accompanied Gen. Wool and staff to the wharf, and then took a tug and proceeded to the Minnesota, where he was received with a national salute.

It is generally admitted that the President and Secretary Stanton have infused new vigor into both naval and military operations here, and that the country will have no cause for further complaint.

The iron-clad gunboat Galena, accompanied by the Port Royal and Arrostook, went up the James river on Wednesday night, and although I have been unable to obtain any positive information from them since she silenced the forts on the lower part of the river, it is understood that the President has received despatches from General McClellan to the effect that they have given him most valuable aid in driving the enemy to the wall. It is even stated to-day that the Galena not only captured the Yorktown and Jamestown, but has put crews on board and ran them up to within shelling distance of the river defences of Richmond. Of the truth of this, however, I cannot vouch, as Old Point is becoming famous for fabulous rumors.

SKETCHES OF NORFOLK AND PORTSMOUTH.

Sketch of Norfolk.

Norfolk is a city and port of entry of Norfolk county, Virginia, and is situated on the right or north bank of Elizabeth river. It is distant about eight miles from Hampton Roads, thirty-two miles from the sea, one hundred and sixty miles by water from Richmond, or one hundred and six miles in a direct southeast line. It is situated in latitude 36 51 north, longitude 76 19 west of Greenwich, or forty-five degrees ease of Washington. The river, which is seven-eighths of a mile wide, separates it from Portsmouth. Next to Richmond, Norfolk was the most populous city in Virginia previous to the rebellion, and had more foreign commerce than any other place in the State. It had also been, in connection with Portsmouth, the most important naval station in the United States, and the harbor was large, safe and easily accessible, admitting vessels of the largest class to come to the wharves. The site of the city is almost a dead level, the plan is somewhat irregular, the streets are wide, mostly well built with brick or stone houses and light with gas. The most conspicuous public building is the City Hall, which has a granite front, a cupola one hundred and ten feet high, and a portico of six Tuscan columns. Its dimensions are eighty feet by sixty. The Norfolk Military Academy is a fine Doric structure, ninety-one feet by forty-seven, with a portico of six columns at each end. The Mechanics' Hall, a Gothic building, ninety feet by sixty; Ashland Hall, and a Baptist church, with a steeple over two hundred feet in height, are also prominent buildings. A new Custom House was in the course of erection by the United States government at the commencement of the rebellion, which would have cost the sum of one hundred and forty thousand dollars. The city contained fourteen churches, nine seminaries, a hospital, an orphan asylum, three banks and two reading rooms. Five newspapers were but recently published at Norfolk. The trade of Norfolk was greatly facilitated by the Dismal Swamp Canal, which opens a water communication between Chesapeake Bay and Albemarle Sound, and by the Seaboard and Roanoke Railroad, which connected it with the towns of North and South Carolina. There are many other items of interest connected with the city which we would like to give, but our space is at present too limited.

Sketch of Portsmouth.

Portsmouth is a seaport and important naval depot of the United States, and capital of Norfolk county, Va. It is situated on the left bank of Elizabeth river, opposite the city of Norfolk. The harbor is similar to that of Norfolk, and the general government had at Gosport—a suburb of Portsmouth—a large and costly dry dock, which was capable of admitting the largest ships. More than a thousand hands were sometimes employed in the construction of vessels at the Navy Yard. This Navy Yard was partially destroyed by fire about twelve months since, was seized by the rebels, and has but now been retaken by the United States troops. Besides the United States Naval Hospital in the vicinity—a large and showy building of stuccoed brick—Portsmouth contained a court house, six churches, a branch of the Bank of Virginia, and the Virginia Literary, Scientific and Military Academy. The town is situated on level grounds, immediately below the junction of the south and east branches of the river. The streets are strait and rectangular. Portsmouth is the terminus of the Seaboard and Roanoke Railroad, the construction of which has increased considerably the business and population of the town. Ferry boats ply constantly from Portsmouth to Norfolk, and a daily line of steamboats connecting with Richmond. Five newspapers were published there before the rebellion. It was founded in 1752, and at last returns had a population of 8,626.

NORFOLK BEFORE ITS CAPTURE.

Despotism Under the Rebel Regime—Rebel Troops Stationed There, &c.

As Norfolk has shared the fate of New Orleans, we give below a statement, so far as we can learn, of the rebel troops that were posted in that vicinity. As our readers are aware, the approaches to that city were guarded by the famous ram Merrimac, the steam gunboats Yorktown and Jamestown, and others of smaller capacity, on the water, and the batteries at Sewall's Point, Craney Island, Pig Point, on the sides of Elizabeth river, and Fort Norfolk, the nearest fortification to the city proper, about one mile to the north. Gosport and Portsmouth (the former of which contains the Navy Yard) are on the westerly side of the river, opposite the city. The city and vicinage were, for many months past, under martial law, Major General Benjamin F. Huger commanding, with Major S. S. Anderson as Assistant Adjutant General. The Provost Marshal of Norfolk was W. A. Parham; of Portsmouth, A. B. Butt.

The following advertisements will tend to throw some light on the condition of things in the city under the rebel regime:—

[From the Norfolk Day Book, May 2.]

DISTRICT OF NORFOLK, May 1, 1862.

The following additional rules are adopted for the markets of Norfolk and Portsmouth:—

I. The privilege of bringing oysters to the market is extended from May 1 to June 1.

II. The butchers in the market are allowed, under the control of the clerk, to purchase pork before ten o'clock.

III. The law will not be so construed as to prevent a man living in the country from bringing his neighbor's produce to market.

W. A. PARHAM, Provost Marshal.

* * * * * *

OFFICE PROVOST MARSHAL,

CITY OF NORFOLK, March 29, 1862.On and after the 1st day of April next, all huckstering will be absolutely prohibited within this military district, and no person will thereafter be allowed, under any pretence, to purchase any articles on their way to the markets of Norfolk and Portsmouth, or within the said district, for the purpose of selling the same again here or elsewhere.

The privilege of selling poultry, eggs, game, fish, oysters, vegetables and fruit will be restricted to those who raise or catch the same, or those in their immediate employment.

Persons violating, or attempting to evade this order will be dealt with in the most summary manner.

The clerks of the markets of Norfolk and Portsmouth, the police and guards, are hereby instructed to use diligence in discovering and giving information of all violations or evasions of this order.

W. A. PARHAM, Provost Marshall.

* * * * * *

HEADQUARTERS, DEPARTMENT OF NORFOLK,

Norfolk, Va., March 18, 1862.No person will be allowed to proceed from Norfolk to Fort Monroe after this date.

By command of

Major General HUGER

BENJ. HUGER, Jr., Asst. Adj. General.* * * * * *

THE NORFOLK NAVY YARD.

Its Extent, History and Condition at the Time of Capture by the Rebels—

Account of Its Destruction, &c.The following particulars in relation to the condition, amount of materials of war, shipping, &c., and other appurtenances peculiar to an immense naval depot, are compiled from the special report of Senator Hale, Chairman of the Committee on Naval Affairs.

THE YARD AT THE TIME OF ABANDONMENT.

This yard was one of the oldest naval depots in the country, and since its original establishment had been very much enlarged in area. At the time of its abandonment, on the 20th of April, 1861, it was about three-fourths of a mile long and one-fourth wide, being by far the most extensive and valuable yard in the possession of the United States. There was connected with it a dry dock of granite like the Charlestown dry dock. The yard was covered with machine shops, dwelling houses for officers and storehouses of various kinds. There were in it two ship houses entire and another. In process of erection, marine barracks, said loft, riggers' loft, gunners' loft, numerous smiths' shops and sheds, carpenters' shops and sheds, machine shops, timber sheds, foundries, dispensary, sawmill, boiler shop, burnetizing house, spar house, provision house, numerous dwellings, and a large amount of tools and machinery. There were also great quantities of material, provisions and ammunition of every description.

According to the returns received at the Ordnance Bureau of the Navy Department, it appears that there were seven hundred and sixty-eight guns in the yard. Other evidence, however, taken by the committee, goes to show quite conclusively that there were in the yard at the time of the evacuation at least two thousand pieces of heavy ordnance, of which about three hundred were new Dahlgren guns, and the remainder were of old patterns. Captain Pauling walked about among them on the 18th of April, and estimated that there were between two and three thousand. Captain McCauley, who must be supposed to have had ample means of knowledge on the subject, thinks there were nearly three thousand pieces of cannon. Mr. James H. Clements, a reliable and intelligent man, testifies that he was familiar with the guns at the yard, and thinks he speaks within bounds when he puts the number of them at eighteen hundred; and he explains very satisfactorily the discrepancy between the account in the Ordnance Bureau and the estimates of the witnesses already mentioned, and of others who appeared before the committee, stating the number of guns variously at from fifteen hundred to three thousand. Upon the whole evidence, the committee are forced to the conclusion that there were as many as two thousand pieces of artillery, of all calibres, in and about the yard at the time of its abandonment, comprising the armaments of three line-of-battle ships and several frigates.

NUMBER OF SHIPS IN THE YARD.

There were also lying at the Navy Yard at the time the new steam frigate Merrimac, carrying forty guns, and worth, when fully equipped, twelve hundred thousand dollars ($1,200,000); the sloop-of-war Plymouth, of twenty-two guns; the sloop-of-war Germantown, of twenty-two guns, and the brig Dolphin, carrying four guns. These were all efficient and valuable vessels. The battery of the Merrimac was not on board, but she was in readiness to be taken out from the yard. The armaments of the Germantown and Dolphin were on board, and they only awaited their officers and crews to be ready for sea. The Plymouth was nearly ready for sea. The old ship-of-the line Pennsylvania was in commission there as receiving ship, and the ships-of-the line Delaware, of eighty-four guns, and Columbus, of eighty guns, and the frigates United States, of fifty guns; Columbia, of fifty guns, and Raritan, of fifty guns, were lying in ordinary at the yard. The unfinished ship-of-the line New York was also lying on the stocks in one of the ship houses. The sloop-of-war Cumberland, carrying twenty-four guns, was at that time the flagship of Captain Pendergrast, in command of the Home squadron, and was moored abreast of one of the ship houses, at a distance of one or two hundred yards from the shore, with her full armament and crew on board, and in a position to command completely the cities of Norfolk and Portsmouth.

VALUATION OF PROPERTY.

The total value of the property of the United States in and about the yard, including the yard itself and all the improvements, and on the supposition that there were but seven hundred and sixty-eight pieces or ordnance, is estimated by the Navy Department to have been on the 20th of April, 1861, nine million seven hundred and sixty thousand one hundred and eighty-one dollars and ninety-three cents ($9,760,181.93). In this aggregate are included the vessels, estimated at one million nine hundred and eighty thousand dollars ($1,980,000); ordnance and ordnance stores, at six hundred and sixty-four thousand eight hundred and eighty-three dollars and seventy-eight cents ($664,883.78); and stores on hand belonging of the Bureau of Construction and Repairs, at one million five hundred and seventy-four thousand four hundred and seventy-four dollars and twenty-nine cents ($1,574,474.29).

THE CRISIS OF SURRENDER AT HAND.

Capt. McCauley was the officer in charge of the yard at the time of abandonment to the rebels.

The sloop Cumberland, of twenty-four guns, one of the most effective ships in the service, and at that time the flagship of Captain G. J. Pendergrast, who was in command of the Home squadron, arrived at Hampton Roads on the 23d of March, 1861, and, by direction of Captain McCauley, was moved on the 31st of the same month up to the naval anchorage, one and a half mile below the Norfolk Navy Yard, for repairs. On the 17th of April following the Cumberland was moved up to a position abreast of one of the ship houses, within one or two hundred yards of the shore, and, with a full armament and crew on board, lay in such a position as to command the entire harbor, the cities of Norfolk and Portsmouth, the Navy Yard, and the approaches to it. For several weeks the Convention of Virginia had been in session, and by its violent debates had blown the excitement all over the State to a blaze. At Norfolk particularly the public feeling against the government was intensely bitter. The military companies of Portsmouth and Norfolk were called out and paraded under arms; rumors were circulated of a contemplated attack upon the Navy Yard and of the erection of batteries at St. Helena, so as to bear upon the yard; and threats were boisterously made of an immediate assault if the authorities at the yard should make any attempt to defend themselves or to remove any portion of the public property. Some light boats were sunk in the river between Sewall's Point and Craney Island, for the purpose of obstructing the channel, on the night of the 16th of April. The Merrimac was put in readiness to be sent out of the harbor on the 17th of April. The Virginia Convention had, in secret session, passed the ordinance of secession on the 16th of April, and proceeded at once to set on foot preparations for attacking or reducing the yard. The Southern officers in the yard, having accomplished their purposes by remaining, resigned on the 18th of April, and on the same day General Taliaferro arrived at Norfolk to take the command of troops which it was undoubtedly the design of the State authorities to send there for capturing the yard. On the following day most of the employees absented themselves from muster, and it was evident that a crisis was at hand which would call for some decisive action on the part of the commandant of the yard.

THE DESTRUCTION OF THE SHIPPING, DOCKS, ETC., BY OUR TROOPS.

Seeing the state of public opinion against the government, and the unprotected state of affairs at the yard, there seemed to be no course left for the Union naval authorities at Norfolk but to destroy all the property belonging to the government at that depot, in order to prevent its falling into the hands of the rebels. Accordingly the work of demolition was commenced, and the immense works which had cost the Union so much to erect were destroyed or set on fire.

In the first place an attempt was made to mutilate the guns in the yard by knocking off the trunnions. For this purpose one hundred men were detailed from the Cumberland, under the command of Lieutenant John H. Rushammer with eighteen pound sledges upon the Dahlgren guns, they resisted all their efforts, and such was the strength and tenacity of the metal that they did not succeed in breaking a single trunnion. Many of the old guns, however, were destroyed. The duty of mining and blowing up the dry dock was given in charge to Captain Charles Wilkes, and officers and men were assigned to him for that purpose, and to prepare for burning the buildings. Commander Rodgers, and Captain Wright, of the engineers, volunteered to destroy the dry dock, and Commanders Alden and Sands were directed to provide for the destruction of the ship houses, barracks, &c. Lieutenant Haney A. Wise was ordered to lay trains upon the ships and fire them at a given signal, and perform that duty in the most thorough and effectual manner.

At about two o'clock all was reported to be ready, and the troops, marines, sailors and others at the yard were taken on board the Pawnee and Cumberland, leaving on shore only as many as were required to set the fires. The Pawnee then left the wharf, and at four o'clock on Sunday morning, April 21, took the Cumberland in tow and stood down the harbor. At twenty minutes past four o'clock the concerted signal was given by a rocket from the Pawnee, the torch was applied simultaneously at many points, and in a few minutes the ships and buildings in the yard were wrapped in flames. The parties left on shore to apply the matches all succeeded in making their escape except Commander Rodgers and Captain Wright, who failed to reach the boats left to bring them off, and were arrested in the morning at Norfolk and detained by the rebels as prisoners of war. The officers and men in the boats pulled down the harbor in the light of the conflagration, which was illuminating the country and the bay for miles around, overtook the Pawnee at Craney Island, and were taken on board.

A singular fatality seems to have attended this mad attempt to destroy the public property, which confined its operation principally to the vessels, which, before the scuttling, could easily have been saved, while the dry dock, the machine shops, smiths' shops and sheds, carpenters' shops and sheds, timber sheds, ordnance building and foundries, sawmill, provision house, spar house, tools, provisions, dwellings of the commandant and other officers, and in fact all the buildings in the yard, except the ship houses, marine barracks, riggers' loft, sail loft and ordnance loft, remained uninjured, and have been ever since in the use and possession of the rebels. Indeed they immediately took possession of all the buildings and machinery, and have ever since been and are now using them for all the usual purposes of a navy yard, employing them in the manufacture of arms, shot and shell, in building gunboats and iron cladding vessels-0f-war to be used against the government. The guns have been mounted on batteries along the Elizabeth river, and distributed among the various fortifications throughout the seceded States.

VALUE OF PROPERTY TAKEN BY THE REBELS.

The worth of the land which fell into the possession of the rebels is given as follows:—

Navy Yard proper, containing 86 acres - $246,000.

St. Helena, containing 38 acres - $12,000.

Naval Hospital, containing 100 acres - $20,000.

Fort Norfolk, containing 6 acres - $10,000.

Total - $288,000.The estimates of the improvements are:—

Improvements at Navy Yard - $2,944,800.

Improvements at St. Helena - $8,300.

Improvements at Naval Hospital - $622,800.

Improvements at Naval Magazine - $136,580.

Total - $3,938,480.The worth of the vessels partially destroyed is thus estimated:—

Merrimac, steam frigate - $225,000.

Plymouth, first class sloop - $40,000.

Germantown, first class sloop - $25,000.

Pennsylvania, line-of-battle ship - $6,000.

Delaware, line-of-battle ship - $10,000.

Columbus, line-of-battle ship - $10,000.

Columbia, frigate - $5,000.

Dolphin, brig - $1,000.

Powder boat - $800.

Water tank - $100.

United States - $10,000.

Total - $332,900.The value of the steam engines and other apparatus is estimated at $250,676. The following is a recapitulation of the rebel gains:—

Value of territory - $288,000.

Value of buildings and other improvements - $3938,480.

Value of vessels - $332,900.

Value of engines, machinery, &c. - $250,676.

Total - $4,810,056.And not the hearts of all must rejoice that this important point, after being over one year in rebel keeping, has again been restored to its rightful owners. It will no longer be the headquarters for rebel naval preparations, but under the broad folds of our national emblem will once more send forth from its docks vessels-of-war to protect the integrity and honor of that Union which has of late been so terribly attacked.

SKETCH OF THE MERRIMAC.

Now that the so-called modern "Colossus of Roads" has been so summarily disposed of by the rebels, a sketch of her will be interesting. The Merrimac was formerly the United States frigate of the same name, which, it will be recollected, was partially burned, and then sunk at the time of the destruction of the Gosport Navy Yard, by the officers of the United States government, in order that she might not fall into the hands of the secessionists. The Merrimac was one of the finest steam frigates in our navy, being 3,200 tons burthen, and carrying forty large guns. She was built at Charlestown, Mass., and launched in 1855. She sailed from Boston on a week's trial trip February 25, 1856, returned, and again sailing, arrived at Annapolis on the 19th of April following. While at Annapolis the Merrimac was visited and admired by a large party, including nearly all the members of both houses of Congress, then assembled at Washington. She sailed for Havana on the 6th of May, 1856, returned to Boston on the 7th of July following, sailed thence for England the 9th of September of the same year, and returned to Norfolk from St. Thomas, West Indies, on the 15th of March, 1857. Leaving Norfolk, she arrived at Boston during the same month, and sailed again from Boston for the Pacific as flagship of Captain Long, on the 17th of October, 1857. Returning from the Pacific squadron, she arrived at Norfolk on the 6th of February, 1860. This was the last cruise of the Merrimac. In April, 1861, she was lying at Norfolk awaiting her battery and the repair of her engines to enable her to proceed to sea. While the extraordinary events pointing to hostilities which have hitherto been narrated were occurring, fears were excited for the safety of the Merrimac, as well as the other vessels-of-war at Norfolk, and it was determined by the department to get her ready as soon as possible, and have her taken out and around to Philadelphia. With that view the Secretary of the Navy despatched Engineer-in-Chief B. F. Isherwood to Norfolk on the 12th of April, with written orders of that date to Captain McCauley to have the Merrimac removed from Norfolk to Philadelphia with the utmost despatch, and to have Mr. Isherwood's suggestions for that end promptly carried into effect. Mr. Isherwood was directed to put her machinery in order as soon as possible, and was accompanied by Commander Alden, of the navy, who was instructed to take command of the ship when ready for sea, and bring her around to Philadelphia. Mr. Isherwood arrived at Norfolk Sunday morning, April 14, and, in company with Mr. Danby, the chief engineer of the yard, immediately made a survey of the Merrimac. On Monday morning the work was commenced on her, under Mr. Isherwood's direction, and continued to be steadily urged, day and night, till Wednesday afternoon, the 17th of April, when the machinery was in a state of readiness to steam to Philadelphia, but owing to circumstances which are not yet very clearly stated, she was finally scuttled and sunk by United States officers, to be clothed afterwards by the enemies of the country with that heavy armor of iron which rendered her so formidable as to destroy, recently, with very little effort, two of our most valuable ships, as well as endangering our commerce. Soon after the rebels took possession of the yard the Merrimac was raised and converted into an iron-plated man-of-war of the most formidable character, having cost the rebel government $185,000. Immediately after being raised she was placed upon the dry dock, and covered with a slanting roof of railroad iron three inches thick, the weight of which nearly broke her down upon the dock, so that it was found almost as difficult to launch her as it was to launch the Great Eastern. Owing to some miscalculation when launched she sank four feet deeper than before, and took in considerable water. She was, in consequence, obliged to be docked a second time, and being hogged and otherwise injured in the operation the Southern newspapers pronounced her a failure. Her hull was cut down to within three feet of her water mark, over which the bombproof house, before mentioned, covered her gun deck. She was also iron-plated, and her bow and stern steel-clad, with a projecting angle of iron for the purpose of piercing a vessel. She had no masts, and there was nothing to be seen over her gun deck but the pilot house and smoke stack. Her bombproof was three inches thick, and consisted of wrought iron. Her armament, at the time of her engagement with the Cumberland, Congress and Monitor, consisted of four eleven-inch navy guns, broadside, and two one-hundred-pounder Armstrong guns at the bow and stern. Last November she made a trial trip from Norfolk, running down so close to Fortress Monroe as to be seen with the naked eye, but ventured no nearer. Although she was looked upon by the rebels as a very tough customer for a vessel or vessels not protected as she was, she remained inactive, anchored off Norfolk, until her engagement, off Hampton Roads, with the Monitor.

Her engagement with the Cumberland and Congress, on the 8th of last March, proved how formidable an engine of was she was made, resulting in the destruction of the two magnificent ships, and the death of many of the noblest and bravest men who ever trod the deck of a man-of-war. Her engagement on the following day would, no doubt, have been as disastrous to our remaining vessels, had not the little Monitor arrived so opportunely, which vessel, after a sharp encounter, in which she and the Merrimac were frequently not more than thirty or forty yards apart, disabled the Merrimac, and forced her to retire under the protection of the guns at Sewall's Point. In this engagement the Merrimac, it is said, lost her steel-clad prow in striking the Monitor a slanting blow. Shortly after her engagement with the Monitor she was towed back to the Norfolk Navy Yard to repair her damages, where she received a more formidable prow, as also a heavier armament. The Charleston Mercury, in speaking of her while she was being repaired, says:—

The Virginia is now in the dry dock for repairs. Her iron plates are said to have withstood, with the most complete success, the effects of the terrific cannonading of the enemy, some of the sections only being riven. Her smoke stack and ventilators were riddled by the enemy's balls, so as to give them the appearance, as our informant describes them of huge nutmeg graters. We are glad to learn from the Norfolk Day Book that the large gun, recently cast in Richmond for the Virginia, has been placed in its position on board that vessel. It throws a solid shot weighing 360 pounds. The shot is of wrought iron, long, and has a steel point. This point is not conical, as in the common rifled cannon ball, but shaped like that of the ordinary instrument for punching iron. Recent experiments show this to be a very ugly weapon, even against thick iron plates. The gun for this new projectile, with the two Armstrong guns, put aboard the Virginia since her return from Newport's News, gives her one of the most formidable batteries in the world, in addition to her being perfectly shot and shell proof.

Since she completed her repairs nothing of any immediate interest transpired until yesterday morning, when we were suddenly apprised of her total destruction by the rebels, having been blown up at two minutes to five o'clock on that morning.

The following is, as far as we can learn, a list of her officers:—

Commander—Commodore Tatnall.

First Lieutenant and Executive Officer—C. Ap. R. Jones.

Lieutenants—C. C. Simms, first division; H. Davidson, second division; J. T. Wood, third division; J. R. Eggleston, fourth division; W. R. Butt, fifth division.

Captain—R. T. Thorn, C. S. M. C., sixth division.

Paymaster—Semple, shot and shell division.

Fleet Surgeon—D. B. Phillips.

Assistant Surgeon—A. S. Garnett.

Chief Engineer—W. A. Ramsey.

Master—William Parrish.

Midshipmen—Foute, Marmaduke (wounded), Littlepage, Long, Craig, Rootes.

Flag Officer's Clerk—A. Sinclair.

Engineers—First, Tynana; Second, Campbell; Third, Herring.

Paymaster's Clerk—A. Ubright.

Boatswain—C. Hasker.

Gunner—C. B. Oliver.

Carpenter—Lindsay.

Pilots—Geo. Wright, H. Williams, T. Cunnyngham, W. Clark.* * * * * *

New York, Monday, May 12, 1862.

THE SITUATION.

The capture of Norfolk and Portsmouth, and the destruction of the formidable rebel gunboat Merrimac, which has so long been a terror and an obstruction to our operations at Hampton Roads, is the most important news of the day. As we announced in our extra of yesterday afternoon, Gen. Wool, with a force of five thousand men, whom he landed at Willoughby Point, advanced on Norfolk on Saturday, and after a brief skirmish with a rebel battery at Tanner's Creek bridge, pushed on and took possession of the city without opposition. A delegation of the citizens met him five miles outside of Norfolk, and formally surrendered the place. The rebel General Huger had withdrawn his troops previously, and Brigadier General Egbert L. Viele was put in command by General Wool, as military governor of Norfolk. The city was found to be uninjured, and the Gosport Navy Yard in perfect condition and good order. The rebels, finding that they could not save the Merrimac from capture, set her on fire at three o'clock yesterday morning, and she blew up in two hours after. President Lincoln in person selected the landing place for our troops at Willoughby Point, and was among the first to step ashore.

THE CAPTURE OF NORFOLK.

Our Special Army Correspondence.

Norfolk, May 11, 1862.I think that there can be no better preface to this letter than may be given in a few words of a friend, who when told of the occupancy of Norfolk by our troops, exclaimed, "And we may thank Honest Abe Lincoln for the same."

THE VISIT OF THE PRESIDENT TO FORTRESS MONROE.

When President Lincoln, accompanied by Secretaries Stanton and Chase, arrived at Fortress Monroe in the revenue cutter, all were glad to see the party, who were shown by General Wool the features of the fortress and surroundings; but "Old Abe" desired to know "Where is Norfolk; we want the place; it may be easier taken than the Merrimac; and, once in our possession, the Merrimac, too, is captured; not, perhaps, actually, but virtually she is ours."

PRELIMINARY STEPS TO CAPTURE NORFOLK.

So our President set himself busily to work, and, with Secretary Chase, upon the cutter Miami, made personal reconnaissance of the whole shore from Sewall's Point to Linn Haven Bay, to see whether the character of the coast would permit a speedy landing of troops, with the necessary paraphernalia. No place could be found—so thought the man; but our President, who has that rare article, good common sense, thought differently. "Those old canal boats that I saw near the wharf at the fort do not draw more than a foot of water when they are entirely empty. These may easily be placed in such a position at high water that the ebb tide will leave them—or, rather, the one nearest the shore—entirely dry, while at the outer one, which may be securely anchored, there will be a depth of sever or eight feet—plenty for the numerous fleet of light draughts that we have at our Disposal." With this in his mind, it was most desirable that the landing selected should be easily covered. "Ocean View" was the place. Yet after this decision for this place was made a further search was made that the best place might be surely ascertained.

THE PLAN OF OPERATIONS.

When all was ready, General Wool, who had thrown his whole soul into the undertaking, made, with the other officers of rank about him, a plan, to be varied by circumstances, should it be in any way expedient to do so. The whole command was ordered to be held in readiness for instant embarkation, with cooked rations for three days, and on Thursday evening, the 8th inst., just as the twilight was deepening into night (it being very desirable to embark without the cognizance of the rebels at Sewall's Point).

EMBARKATION OF TROOPS.

The troops under the command of General Max Weber were marched to the wharf, and placed upon the transport for immediate departure; and never do I remember to have seen finer men in better spirits; but they did not move—why no one could tell—and the men were kept upon the boats and pier all night long.

OUR TROOPS DISAPPOINTED.

In the morning they were marched back to camp, a very disappointed party of "sogers." I am told, though, by those in whom I place confidence that General Wool knew of more that was going on than we could with our limited facilities. We found, too, that the Merrimac had been out all night; and the following day she went back to Craney Island.

RE-EMBARKATION OF TROOPS.

Friday evening the men were marched again to the place of embarkation. The steamer Adelaide, one of the "Bay line" boats, of light draught and large capacity, was detained to be used as a transport.

SAILING OF THE EXPEDITION.

By ten o'clock the completion of arrangements was announced, and the men were stowed snugly, most of them sleeping soundly, it being very desirable to bring them on the morrow into the field in the best possible condition. A couple of hours passed quietly. Fort Wool, on the Rip Raps, had ceased to pour shot into the works on Sewall's Point for some time, when we dropped so quietly away from the wharf that few, if any, of the sleeping braves were awakened—the Lioness tug leading the way, with the pilot of the expedition on board; the George Washington following her close by, having in tow a number of canal boats and barges. After her, in line, came the numerous fleet of little craft, nearly all of the steamers having in tow canal boats. In a little more than an hour we were at anchor off the point selected for our debarkation.

LANDING ON SECESH SOIL.

A barge was sent ashore with a number of Captain Davis' company, the Richardson Light Artillery, who being equally as well drilled in light tactics as in the handling of the heavy guns, had volunteered for the occasion. The Captain at once made such a disposition of his men as to entirely preclude the possibility of surprise. The canal boats were drawn into position and joined one to the other, each overlapping in such a manner as to be perfectly firm and secure. The larger steamers being anchored quite a distance off the shore, the light draught of the smaller tugs was made available, and a steady column of soldiers was soon crossing the President's pier, stepping noiselessly upon the beach with dry feet.

The Miami, anchored off the landing, covered it completely with her guns. The Twentieth regiment New York Volunteers were the first to land after Captain Davis' company, when they were thrown forward, that those landing afterward might find the position perfectly protected, and not in any way encumbered. Halting for a short time to break the morning fast, they pressed on, the other regiments of Max Weber's brigade following as fast as the little duty of breakfast had been accomplished.

WHAT THE GENERAL DISCOVERED ON LANDING.

General Weber, with the Twentieth, found that the place had been deserted but a few hours, perhaps moments, and the men shoved on with an eagerness that was truly creditable to them.

The road, a country one, cut through the woods to our landing place. Ocean View, was in many places exceedingly muddy.

SUMMER RESORT OF THE "NATIVES."

A word here of the dilapidated pleasure resort of the people of Norfolk—Ocean View. An old barn of a tavern (a hotel they call it—a more rickety one I have not seen for many a day)—and a few surrounding buildings comprised the settlement, which was peopled by two old aunties and their attendant "picks," who, as our men strode past, quietly smoked their pipes and greeted us with a "Yah! yah! Mass, got furter; run bery gast for cotch him buckra what lef yere."

THREE MILES FURTHER—A DESERTED REBEL CAVALRY CAMP.

A march of three miles, and we came to a deserted camp of a rebel cavalry company, built of logs, the huts being ranged upon one side for the accommodation of the men, while directly parallel ran a line of stables. The shanties of the men had evidently been but a short time evacuated; in fact, the nests were warm. In one of the huts your correspondent found a secesh blade, rather too heavy for comfortable carving; so I left it, with my best wishes, with one of the cavalry men who were accompanying us.

OBSTRUCTIONS ON THE MARCH.

A short distance further we came to a portion of the road that had been obstructed, trees having been felled; but the ready aces of our pioneers soon dislodged the trees, and the road was clear for the troops that were now coming into view through the leaves of the forest. When we advanced thus far and met no resistance, when the place was so admirably adapted for it, I made up my mind that we were not to meet the "rebs" until we were within a very short distance of Norfolk.

GEN. WOOL AND SUITE JOIN THE ADVANCE GUARD.

At seven o'clock General Wool, accompanied by Secretary Chase, Generals Mansfield and Viele, landed at Ocean View, and they were soon on the way to the front, the men cheering them as they passed.

Upon the arrival of the party at the Halfway Crossroads, they were distant from Ocean View five miles, and by the short road to Norfolk the same distance from that place.

The Halfway Crossroads is as picturesque a spot as one often sees—a greater portion of the place being sheltered by magnificent willow oaks, the largest that I remember to have seen. Under these trees were grouped, in the coziest manner, the Twentieth regiment.

REBELS CAPTURED—WHAT THEY SAID.

As General Wool and others drew rein, General Weber was questioning some dirty-looking fellows in gray that had been taken prisoners. From them he learned that they were a portion of the garrison of Sewall's Point, which had been evacuated by reason of our shelling of the night previous, by which one man had been killed and several wounded. I asked them what all the smoke was about. "Youse fellows throw some kind of things that spil fire when they burst, an' it just sot everything in a blaze; so we run into the woods and then we all run away." Candid, that.

THE BATTLE THAT DID NOT TAKE PLACE.

They said, too, that the Halfway Crossroads was to have been the battle field, but the rebels thought that we were too strong. This spot, I do not think, could be better for a battle, the ground being covered by rifle pits and trenches running in every direction, while to flank them would be next to an impossibility, owing to the nature of the ground. At these forks of the road are two dwellings, with their outhouses, but no inhabitants.

A BULL RUN CONTRABAND SPEAKS.

A negro who had been captured, also in the uniform (who had carried a musket at Bull run), upon being questioned, said that by the road leading to the right it was five miles to the city; the one to the left, being rather roundabout, was eight miles. If we went by the nearest route we had to cross a bridge that he said was already in flames, which we were easily satisfied of by a glance at the sky in that direction, which was clouded with a dense volume of smoke.

A RAPID FORWARD MOVEMENT.

A moment of consultation, and Generals Mansfield and Viele rode rapidly forward, with an escort of cavalry, one or two regiments following. The distance to the bridge was about three miles, through charming scenery. The road was strewn with the thrown-away articles which the men left untouched in the road and bushes. A very pretty little church, about which the rebels had made a very picturesque little camp, and I think that I do not exaggerate when I say some two or three hundred graves, were passed.

SKIRMISHERS THROWN OUT.

Arriving at a point some quarter of a mile from the bridge, we were joined by Secretary Chase, Major Herrmann, of General Wool's staff, being at this point with a detail from the Twentieth—The Sixteenth Massachusetts being held in reserve, with the company of Captain Davis, a short distance to the rear.

THE ENEMY IN SIGHT—THEY OPEN FIRE.

The skirmishers were being thrown forward by Major Herrmann, when the enemy opened with two howitzers and a rifled field piece stationed a short distance to the other side of the bridge, and nearly a mile from us. The bridge was in flames, and we without the necessary artillery to drive off the enemy for the purpose of constructing a temporary bridge, and the rebels enjoying an artillery practice without a shot in return; but where there is a will there is a way; and we soon found a good road, only a trifle farther.

A RIGHT ABOUT MOVEMENT.

And back we went, without firing a shot. Having, by a careful reconnaissance, assured ourselves that the thing that we were after "was not to be trifled that way," at the "Half Way," we took.

A HASTY CAMP DINNER.

The men rested out the midday and disposed of a large quantity of "hard Jack" and bacon, washed down with coffee. Milk in it, too. Secesh left his cows without milking in the morning, so that the poor creatures were gratefully accommodating to our boys, who "left nary a drop in the well." After a good rest and a not too hearty meal, the houses that I have mentioned before were made the depository of the knapsacks, &c., it being very desirable that the men should be perfectly free to attack the line of defences known to be but a few miles in front.

REINFORCEMENTS SENT FOR.

General Wool determined, upon consultation, to send for a portion of General Mansfield's troops to come up as a support, in case of serious resistance from the enemy in their works.

General Mansfield, accompanied by Captain De Kay, proceeded at once to Fortress Monroe to consult with the President and act upon his instructions. Meanwhile the Thirty-eighth Pennsylvania Volunteers, Colonel Jones, and the Ninety-ninth New York (Union Coast Guard), under Colonel Wardrop, had come up with a squadron of cavalry under Major Dodge. By request of General Wool, General Max Weber detached from his brigade a command of two regiments for Gen. Viele—the Tenth New York, Col. Bendix, and the Sixteenth Massachusetts, Col. Wyman.

DETAILS COMPLETED FOR A SECOND ADVANCE.

The necessary details having been completed, the column advanced in the following order:—The cavalry under Major Dodge, then the brigade of Gen. Viele, the Tenth New York being in advance. When within two miles of the works the column was halted in the woods for a rest. The Twentieth New York then took the advance, and the cavalry, with General Wool and Secretary Chase, rode rapidly forward.

THE REBEL WORKS EVACUATED.

A short examination of the works that we now came in view of satisfied General Wool that they were evacuated. The cavalry were at once pushed forward, and the works found to be abandoned. Cheer upon cheer rose from the men as they shoved on through the dust into the works, which we found to be of the strongest kind, not entirely armed, but quite sufficiently so to have resisted with success the very small force that we then had in front of it.

DESCRIPTION OF THE WORKS.

The extent of the works, which are known as the intrenched camp, must be some three miles. In the work we found the barracks entirely deserted. The country people had turned out to see the Yankees come, and the darkeys were in a big state of hilarity. From this place to the city, a distance of about three miles, a plank road is laid. It was not the intention of the General to enter the town that night, but, the word that the rebel soldiers had left being brought to him, he determined to shove forward at once. The cavalry of Major Dodge was thrown in front. Generals Wool, Viele and Weber, accompanied by Secretary Chase, followed and after them came the Twentieth New York regiment, under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Weiss. The cavalry were almost entirely concealed from view by the dense cloud of dust.

OUR SOLDIERS HILARIOUS.

The Twentieth, notwithstanding the long march, trod lightly, as if they were just out for a dress parade, and with a quiet, yet most melodious voice, sang, as they marched, a number of songs. The "Laughing Song" was being aired by them at the moment that they passed quite a group of country folk, who joined merrily in the laugh, "when it came in." Soon we reached

IN FRONT OF NORFOLK—A REBEL FLAG OF TRUCE.

Near the immediate environs of the city, and in front of a group of low wooden houses we saw a white flag being waved. Upon advancing it was found to be a deputation of citizens, composed of the Mayor and a portion of the Common Council, who had come out from the city to see what terms would be demanded, and to present a letter from General Huger, the purport of which was the fact that, being unable to retain possession of the place, he had surrendered it into the hands of the city authorities. They in turn, upon being made acquainted with the requirements of the government, were ready to place the city once more under the control of the federal government.

FORMAL SURRENDER OF NORFOLK.

The scene in the little room in which the parties first met was unique in the extreme. The officers were thoroughly bepowdered and fatigued, and Mr. Chase's fine features were funnily disguised with the pulverized dust that had settled on all alike—the Mayor nervously anxious, the Councilmen stubbornly so; the proprietor of the shanty"sans habit," fist in his pocket and quid in his cheek.

WHAT WAS SEEN ON ENTERING THE CITY.

As we entered the city the smoke of the burning Navy Yard seemed a cloud about to fall with the suddenness of wrath, and blot out the stain of treason with which the air seemed full. Fortunately for us, it did not this time. So we went on. The children scattered, some of the boldest stopping an instant to say, "They ain't agoing to hurt you." Then they grew more bold, as the young procession trailing after us grew in length. The tramp of the cavalry escort, as it came in the distance, attracted attention, too. Blinds slammed, and the people peeped rather than looked. The crowds upon the corners were quiet, through the city to the City Hall, and in a moment the carriages and escort came up. A general rush was made by the people, who by this time were out in force; but the Mayor, Mr. Lamb, turned quietly to them, and in a few words explained that General Wool and staff must enter alone, as they were to draw up the articles by which they were to be protected, and that the people were to have more privileges than even he had hoped for. With a cheer the steps of the building were vacated in an instant, and the party, weary and dusty, entered the chamber, accompanied by two or three officials only.

CONSULTATION BETWEEN GENERAL WOOL AND THE MAYOR OF NORFOLK.

After a moment they were left entirely alone, and a short consultation ended with the preparation of the necessary papers by general Wool and Secretary Chase, when the Mayor was requested to make an examination of the instrument, which he did, expressing himself perfectly satisfied with the contents.

General Wool then proceeded to the City Hall with the Mayor, followed by a large crowd, where he issued the following proclamation:—

HEADQUARTERS, DEPARTMENT OF VIRGINIA,

NORFOLK, May 10, 1862.The city of Norfolk having been surrendered to the government of the United States, military possession of the same is taken in behalf of the national government by Major General John E. Wool.

Brigadier General Viele is appointed Military Governor for the time being. He will see that all citizens are carefully protected in all their rights and civil privileges, taking the utmost care to preserve order, and to see that no soldiers be permitted to enter the city except by his order, or by the written permission of the commanding officer of his brigade or regiment, and he will punish summarily any American soldier who shall trespass upon the rights of any of the inhabitants.

JOHN E. WOOL, Major General.

MILITARY GOVERNOR APPOINTED.Brigadier General Egbert L. Viele was appointed Military Governor of the city and environs, who issued the following proclamation on Sunday morning:—

NORFOLK, Va., May 10, 1862.

The occupancy of the cities of Norfolk and Portsmouth is for the protection of the public property and the maintenance of the public laws.

Private associations and domestic quiet will not be disturbed; but violations of order and disrespect to the government will be followed by the immediate arrest of the offenders.

Those who have left their homes under the anticipation of acts of vandalism may be assured that the government allows no man the honor of, serving in its armies who forgets the duties of a citizen in discharging those of a soldier, and that no individual rights will be interfered with.

The sale of liquor is prohibited. The offices of the Military Governor and of the Provost Marshal are at the Custom House.

EGBERT L. VIELE,

Brigadier General U. S. A. and Military Governor.General Wool and others then took their departure from the city—having arrived at half-past five and left at six. Rather quick work, was it not? After the departure of the party

MAYOR LAMB MAKES A SPEECH—HE ANNOUNCES THE SURRENDER

OF THE CITY TO OUR TROOPS.The Mayor took his stand upon the steps of the City Hall, and told the assembled multitude that "The city was surrendered; he had done as best he could; he had done all in his power to obtain protection for its inhabitants, and believed that they would be dealt with in the most kindly manner." He was about to say more when the cheers drowned his voice, and he left his stand. A few ragamuffin boys then ventilated some sickly cheers for Jeff. Davis, which were received with merriment by the crowd.

The Mayor returned to the room of the Military Governor, General Viele, who had appointed Mr. Theo. R. Davis (formerly upon his staff) Secretary pro tem. To him were given the keys of the public buildings and the business papers of the moment.

OUR TROOPS ENTER THE CITY.

General Viele at once despatched an orderly to General Weber for the cavalry under Major Dodge, the Sixteenth Massachusetts and details from other regiments. The cavalry, upon their arrival, were posted at once by the General himself at the Custom House, railroad depot, and at all other public buildings.

DESTRUCTION OF FEDERAL PROPERTY AT THE NAVY YARD.

The Sixteenth Massachusetts were at once sent to Portsmouth to do what they could to stay the tremendous fire then burning the Navy Yard. The Thomas Selden, one of the boats belonging to the Bay line of steamers, was in flames. The gunboats that were unfinished and could not be moved were destroyed, as were the Brandywine, United States and others—some twenty vessels in all.

Perhaps many of your readers will remember that a few weeks since the rebels cut out a water boat, the property of the contractor, for supplying the navy vessels with water. This was the only vessel at the Navy Yard unburned., and when Mr. Noyes, the contractor, went on board to extinguish what little fire there was, he felt sure of his good fortune; but, alas, he had been on her but a few moments when out burst the flames so strong that their extinguishment was impossible. The Navy Yard was totally destroyed, with all its appurtenances. The dry dock, however, is, I think, uninjured. The city was quiet—more quiet, I am told, than it has been for some time.

HEADQUARTERS OF THE MILITARY GOVERNOR.

General Viele makes his headquarters in the Custom House. The same building was occupied by General Huger as his quarters.

The correspondents all went to the Atlantic Hotel, where the best room was reserved for General Viele; but, owing to the extremely arduous duties that his office had devolved upon him, he was obliged to be in the saddle nearly all night, and only laid down for a few hours' rest in his office.

HOTEL ACCOMMODATIONSTHE GUESTS PREVIOUS TO THE EVACUATION.

The correspondents, who had been starved at the Old Point Hotel, made a "prompt movement" for the Atlantic Hotel, kept by its old host, Mr. Newton, still, from whom I have a few items for your readers' edification. The day previous to our coming (Friday) he had seated at his table one hundred and fifty guests; on Saturday six person only sat down to dinner, and nearly choked themselves in their haste.

EXORBITANT PRICES OF PROVISIONS AND WHISKEY.

He tells me, too, that the prices of provisions are exceedingly dear, as is everything. I give you a sample:—Beef and pork, 30c. per pound; butter, when there is any to be had, ranges from 75c. to $1. Tea is to be had only in very small quantities at $6 per pound; and Mr. N. tells me that he knows of but one chest of the article in the city.

Whiskey!—an article that may be bought easily in Baltimore for forty or fifty cents per gallon—is to be had for six dollars, and only seven barrels in the whole city. Let me give you one more item. The regular country tallow candle, that must be snuffed certainly every five minutes, is bought at the moderate price of sixty cents per pound. This is shinplaster prices, though, which shinplasters are being sold to the soldiers for an immense discount—something like a half dime for a "fifty center." The small boys about town are driving quite a business in that way. The newspapers have, with but one exception, stopped publication, on account of the entire impossibility to obtain the necessary paper. The Day Book still holds its place, and its publisher is printing the orders, &c., for General Viele. Upon retiring for the night I made a sort of a reconnaissance of my domicile, and found upon the door a little card requesting gentlemen not to leave their boots outside. Upon my query to sambo in the morning, I was told, "Hi! boss; boots is $25 a pair like dem of yourn."

A REBEL OFFICER SURRENDERS HIMSELF.

A young man, said to be an officer on board the Merrimac, surrendered himself to Gen. Viele. His name is McLoughlin. He says, "Secesh is a humbug, and he is off for home," which is in Baltimore, as soon as it is practicable.

A VISIT TO PORTSMOUTH AND THE NAVY YARD.

The next day I visited Portsmouth and the Navy Yard. I was told before I went over there that the place was full of Union men; and truly, if one may judge from the bunting which is shown from very many houses and public places, placed in position by the citizens themselves, one may be quite sure that Jeff. Davis and his crowd can have but little sway over the residents, one of whom told me that the day we came the rebels forced the citizens to bring out their tobacco and cotton, which they destroyed by throwing them overboard, and by giving them away in small quantities to the negroes.

At the Navy Yard everything was in the most demolished condition—the Mayor says to the tune of five or six millions, and that they did all that they could to prevent its being done. I am very doubtful, too, whether the people will ever reap the benefits that accrued from the Navy Yard again.

THE STARS AND STRIPES HOISTED ON THE CUSTOM HOUSE.