Just here, also, permit me to introduce an account

by this same eye-witness of the second day's engagement. This account, though

written in thrilling words, is not in accordance with the actual facts,

as I shall show later on in my own description of this day's fight. He says:

"The 'Merrimac,' in her attempt to run down the

'Monitor,' failed entirely. She struck her antagonist fairly and at full

speed, causing, however, but a slight jar. By the collision the prow of

the 'Merrimac' was broken and her mail cut through by the sharp edge of

the 'Monitor,' causing a bad leak. In the desperation of the fight the ships

closed, actually touching sides, hurling shot and shell at each other with

demoniac energy. But these cast-iron missiles glanced or crumbled to powder.

The rebel 'Yorktown' at once attempted to interfere. A single 170-pound

shot from the 'Monitor' passed through the traitor and sent him home to

have his wounds bandaged. The contest was for a time so hot, the muzzles

of the hostile guns almost touching each other, that both ships were enveloped

in a cloud of smoke, which no eye could penetrate. Flash and thunder-roar

burst forth incessantly from the tumultuous maelstrom of darkness, and solid

balls, weighing 170 pounds, glancing from the armor, ricochetted over the

water in all directions for one and two miles. Such bolts were never hurled

from the fabled hands of Jupiter Olympus.

"Thus the duel raged with unintermitted fury

for four long hours. The 'Monitor,' at but a few yards' distance, steamed

around her foe, planting a ball here and a ball there, eagerly searching

to find some vital spot. She tried her rudder, her sides, her screw, just

above the water line, just below the water line. In some of these efforts

she was successful, and at length three gaping holes were visible and the

'Merrimac' was evidently sinking. The rebel was whipped; and firing

his last gun, turned to run away. Unfortunately, just at that moment, as

Lieutenant Worden was looking out at the iron grating of the pilot-house,

a 1oo-pound shot struck point-blank upon the grating, just before his eyes.

The concussion knocked him prostrate and for the moment senseless. He was

also entirely blinded by the minute fragments of iron and powder driven

into1 his eyes, an injury which it was almost impossible to get over. This

occasioned momentary confusion, until the command was assumed by Lieutenant

Green. The 'Merrimac,' which had entered the conflict with a spirit so proud

and defiant, was now limping on the retreat thoroughly whipped and humiliated.

As so much depended upon the single 'Monitor,' it was not deemed wise to

expose her to any risks not actually necessary. She had, therefore, received

orders to act strictly on the defensive, and by no means to leave the immediate

vicinity of the fleet. She, however, pursued her disabled foe a short distance,

throwing into her a few parting military benedictions and then left her

to seek refuge in her rebel anchorage. As Lieutenant Worden after a time

revived from the stunning blow he had received, his first question was:

'Have I saved the "Minnesota"?' 'Yes,' was the reply, 'and whipped

the "Merrimac." ' 'Then,' he rejoined, 'I care not what becomes

of me.' "

The above is miswritten history, and no facts justify

such statements; they have misled our country.

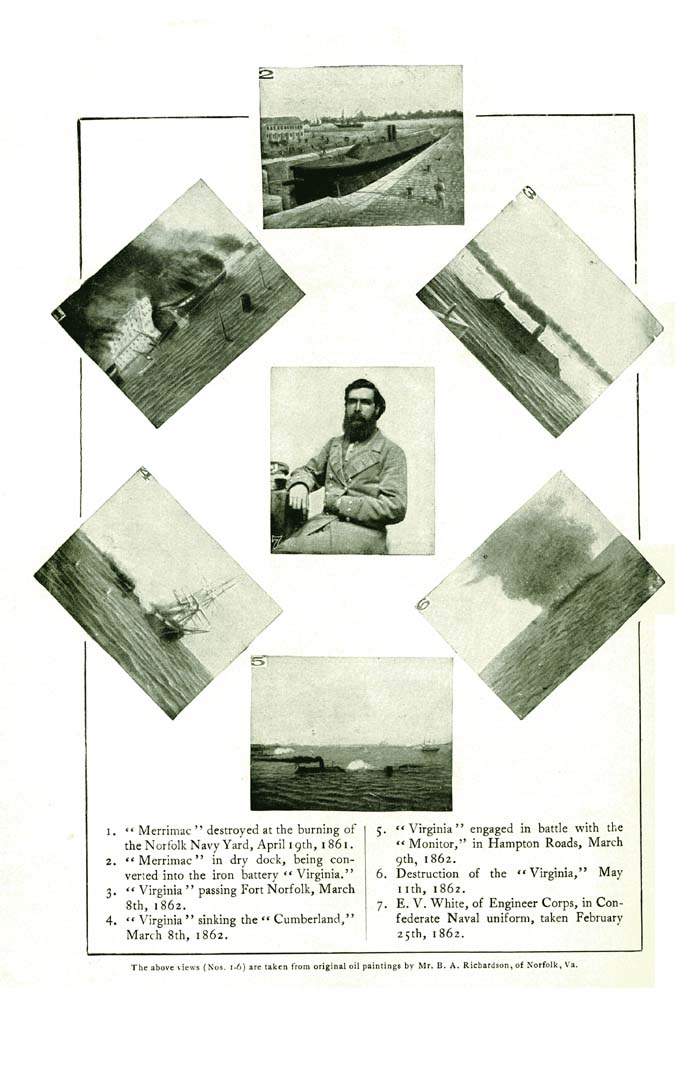

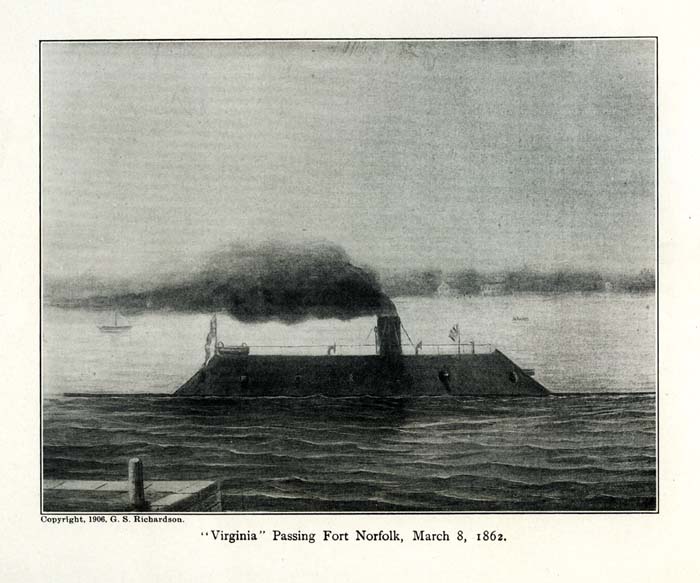

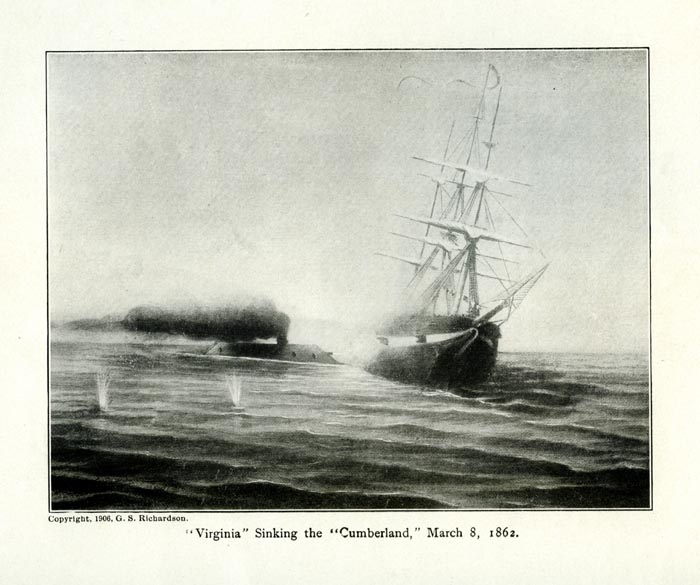

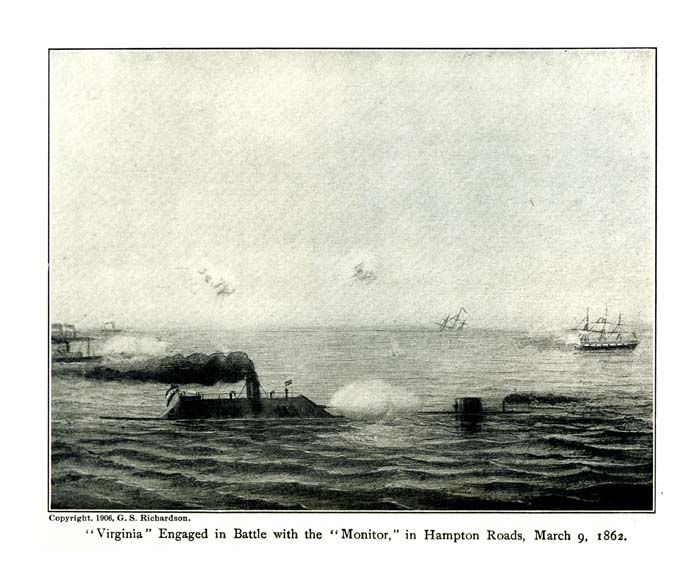

The next morning (Sunday, March 9th) after an early

breakfast, a consultation was held, the command having devolved on the gallant,

able and courageous Catesby Ap. R. Jones, than whom none deserved more honor

for bravery and cool daring, and under whose supervision, as executive officer,

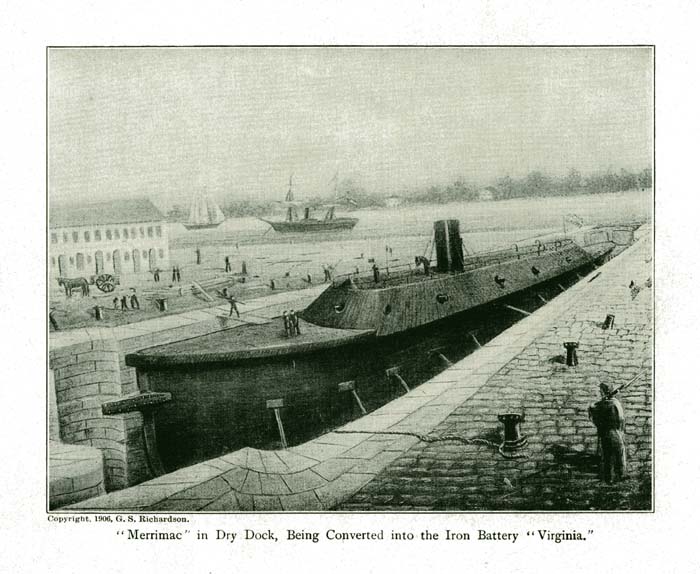

the construction of the armament of the ship was completed. It was decided

to complete the destruction of the now almost abandoned "Minnesota,"

even while our ship was taking water freely at the opening in her bow, caused

from the loss of the cast-iron prow left in the "Cumberland" when

we ran into her. Our pumps had been kept busy during the night relieving

the ship of water. However, we got under way, making for the "Minnesota,"

when suddenly we grounded on what is known as the Middle Ground of Hampton

Roads, and there we stuck for a considerable time. But before we had grounded,

the "Monitor" was discovered coming out from where the "Minnesota"

lay aground, appearing to us, as she has been called, "a cheese-box,"

or a "tin can on a shingle." It was not long before she was recognized

as the Ericsson "Monitor," and we opened fire upon her with our

bow-rifle, but with no effect. Straight on she came toward us, and when

in good position let loose her heavy guns, giving us a good shaking up.

Thus she continued circling around us, and every now and then throwing the

heavy missiles against our sides. We, in response, as she passed around,

brought every gun aboard our ship to bear upon her. It was now "Greek

meeting Greek;" iron against iron. Hundred-pound shot rattled against

the mailed and impenetrable sides of the combatants in this tremendous duel

and glanced off like hail. Never before had ships met carrying such heavy

guns. From both vessels the firing was executed with great rapidity and

with equal skill, with but little effect on either side. However, our weak

points seemed to be known to the commander of the "Monitor," and

so well did he attack these, that soon on the starboard midship, over the

outboard delivery, he so bent in our plating that the massive oak timbers

were cracked, and from this and the continued ricochet shots of the "Minnesota"

considerable concern was beginning to be felt by our commander and all on

board. Soon, however, we were relieved, by the moving of our ship, from

the position which, for such a trying period, we had occupied. Then, with

a settled determination on the part of our commander to run the "Monitor"

down, as a last resort, seeing that our shots were ineffective, I was directed

to convey to the engine room orders for every man to be at his post. We

caught and did run into the "Monitor," and came near running her

under the water; not that we struck her exactly at right angles, but with

our starboard bow drove against her with a determination of sending her

to the bottom, and so near did we come to accomplishing our object that

from the ramming, and shot of our rifle gun that blinded her commander,

she withdrew to shoal water near the "Minnesota," whence, by reason

of our heavy draft, we could not follow—never again to offer or accept

battle with the "Virginia." After waiting on the ground of our

victory, without any signs of her return, for possibly an hour or more,

we steamed up to the Navy Yard, receiving the shouts and huzzas of the thousands

of our people who had witnessed our great triumph.

I wish to emphasize the facts just related

of the purposed collision with the "Monitor" and our

desire to repeat it, and of her withdrawal from the field, and her refusal

then or thereafter to engage in battle with the "Virginia," notwithstanding

this statement is in positive contradiction of the theory generally accepted

at the North, and even published in the school histories of to-day. An incident

on this point will illustrate the prevalence of an incorrect record of the

case. Some years ago, when in New York, I visited the cyclorama illustrating

this fight, then on exhibition. When, during the course of his lecture on

the subject to the spectators, the manager made statements that were not

facts, I interrupted him and called his attention to the same. He asked

me what I knew about it. I answered that I was an officer on board the "Virginia,"

and he politely requested an interview with me. After finishing his talk

he came to me and said he was well aware of the errors he was circulating,

but that in order to make his show popular he was forced to state

what he did.

By 4 o'clock we were back in the dry dock at the Navy

Yard. The grand old ship was a picture to behold. You could hardly put your

hand on a spot on the sides, or smokestack, that had not been battered by

the shot of our enemy.

Large improvements to the "Virginia" were

made under the supervision of Commodore Tatnall, of Georgia, who had assumed

command, owing to the disability of Commodore Buchanan, these improvements

consisting of a new wrought iron prow, port covers, etc. When completed,

she went down to Old Point and offered battle to the "Monitor"

and all the great wooden warships of the U. S. Navy, including the "Vanderbilt,"

which ship had been specially brought forward to accomplish her destruction.

We manned, carefully, four small steamers fully equipped to capture the

"Monitor" by wedging the turret and securing down the hatches,

and while one or more of these boats might have been destroyed, so well

was our late antagonist's build then understood had either reached her she

would, in my judgment, have been captured. Neither the "Monitor"

nor any one of the large ships the U. S. Government had ordered there would

come out from under the guns of Fortress Monroe, while one of our steamers,

the "Jamestown," was sent in near Hampton and captured three schooners

loaded with hay and grain, and brought them safely to Norfolk. After cruising

about, in challenge for battle, without having it accepted, the Commodore,

showing signs of disgust, ordered a gun fired to the windward, and returned

to the buoy off Sewell's Point, and anchored for the night. The next day

we came to Norfolk for some repairs to the boiler. A few days thereafter,

having completed our repairs, we heard heavy firing, and received orders

to go to the aid of our batteries at Sewell's Point that were being bombarded

by the "Monitor" and other ships. We were soon under way and steered

directly for the "Monitor" and others, then shelling at the Point;

but as we approached they ceased firing and retreated below the forts, we

following until we exchanged several shots with the Rip Raps. With considerable

disappointment, Commodore Tatnall ordered the ship back to her buoy at Sewell's

Point. The next day, or soon thereafter, we noticed our batteries were not

flying our flag, and upon learning the cause we found that Norfolk was being

evacuated, thus ending the necessity of holding our present position. The

next thing to do was either to go out to sea, which all agreed to do, if

permitted, or go up the James River. Positive orders were received to come

up to Richmond. Upon consultation with the pilots it was learned that if

we could lighten the ship enough to let her draw four or five feet less,

we could get over the bar. This action was agreed upon, and all were set

to work heaving over the ballast and other articles, in order to bring her

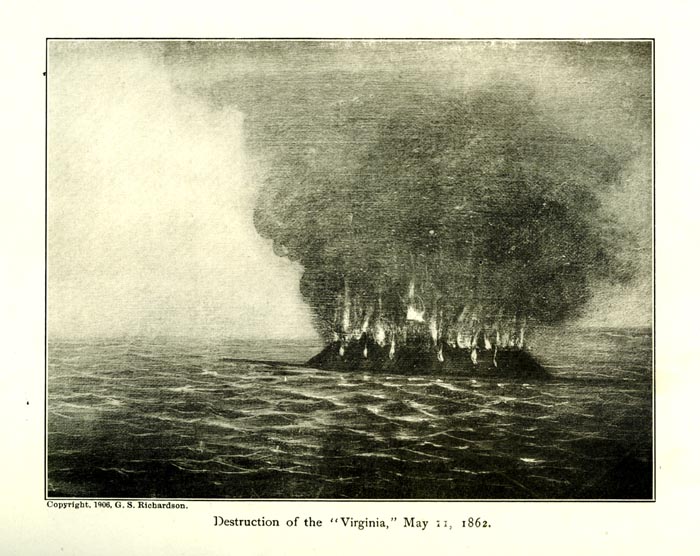

up to eighteen feet draught. We learned by 12 o'clock Saturday night that

we could not get up the river for some reason, and now being exposed by

having some two feet of the wooden hull out of the water, nothing was left

but to destroy the ship, in order to keep her from falling into the hands

of the enemy. She was then run aground, above Craney Island, and the work

of destruction commenced. We had but two boats to land our large crew safely

on shore; consequently we had to leave all our personal effects on board

the steamer. I was one of ten selected to destroy the ship, and held the

candle for Mr. Oliver, the gunner, to uncap the powder in the magazine to

insure a quick explosion, and, necessarily, was among the last to leave

her decks. A more beautiful sight I never beheld than that great ship on

fire, flames issuing from the port-holes, through the gratings and smokestack—the

conflagration was a sight ever to be remembered. Thus closed the life, on

Saturday night, May 12, 1862, of our gallant ship. Our crew landing Sunday

morning, possibly about 4 o'clock, we had to march to Suffolk, arriving

that night, having been without food since Saturday noon. We took the train

and arrived at Richmond the next day, and were ordered to Drewry's Bluff,

and there we prevented the enemy from reaching Richmond, stopping the progress

of the entire fleet, including the "Monitor" that had refused

to meet the same men when on the decks of the "Virginia" before

her destruction. With considerable loss to them, and but little to us, we

drove the entire fleet back down the river.