A TRIBUTE TO THE MONITOR 150 YEARS LATER, DECEMBER 30, 2012

Index:

Dedication

Brochure

The Virginian-Pilot, December 30, 2012. Author Paul Clancy.

The Virginian-Pilot, December 30, 2012. Author Margaret Matray.

Blog #24, December 31, 2012.

Photos

* * * * * *

December 29, 2012

This program was sponsored by the National Marine Sanctuary Foundation & Preserve America Initiative.

___________________________________________________________

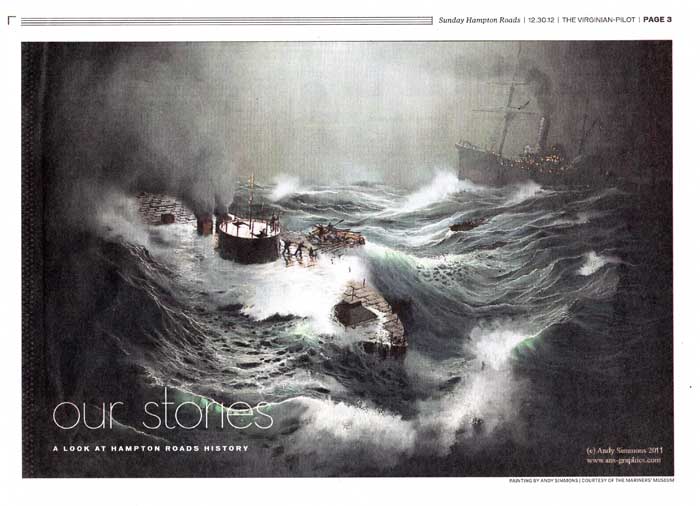

The Virginian-Pilot, December 30, 2012

IRONCLAD'S DOOM CALLED "A

PANORAMA OF HORROR"

Permission granted by author Paul Clancy to reprint this article & Andy Simmons for use of photo.

One thing many of us in Hampton Roads have in common is putting out to sea. Whether on a Navy ship, cruise ship or sailing vessel, we've crossed the invisible barrier between bay and ocean, caught a glimpse of the Virginia Capes and let the thrill of adventure creep into our hearts.

And maybe, just maybe, a sense of dread.

Both of these emotions must have played on the mind of the officers and crew of the ironclad ship Monitor as the morning of December 30, 1862 - 150 years ago today - dawned clear and promising. They had parted company with the Capes in late afternoon the day before, and observed purple and crimson clouds as the sun set. It had been a balmy 58 degrees, and the sea looked like glass.

At dawn, there was a slight swell and a faint breeze from the southwest, but nothing to worry about. Sailors who had been cramped in the smoky engine room came out on deck and breathed the clean fresh air deeply.

But there was something else going on that only paymaster William Keeler seemed to notice: a bank of dark clouds in the western sky that gradually increased until it obscured the sun with its "cold gray mantle." A cold front was approaching.

By afternoon out on the Atlantic, winds began to freshen, with speeds up to 16 knots. That's nothing for most ships, or even many small boats, but for the half-submerged Monitor, it signaled trouble. For sailors now confined below while the ship pitched and yawed in the growing seas, it must have gone from slightly uncomfortable to just god-awful.

When the officers went down to dinner at sunset - around 4:45 p.m. - the talk was still of adventure, about how they were going to battle their way back to the glory they felt after the titanic clash with the Virginia, the South's ironclad. But when they climbed to the turret afterwards, all hell was breaking loose.

Seas were rolling over the deck and crashing into the turret. Gloom hung over everything and, as surgeon Grenville Weeks put it, "the moan of the ocean grew louder and more fearful."

An hour before midnight, a call of distress was sounded. The log on the tow ship Rhode Island shows that the Monitor "was in a sinking condition." Lifeboats were called out, and a treacherous dance of small boats and the ominously plunging ironclad began.

Most terrifying of all, several who tried to dash across the deck to the lifeboats were carried overboard by waves. Those who witnessed it were paralyzed by fear and refused orders to leave the turret. It was, as Keeler would write to his wife, "a panorama of horror."

Incredibly, some of the engine room crew stayed below as long as they could to keep the fires in the boilers going. All power on the doomed ship had been directed to the pumps, and these courageous acts may have bought a little bit of time.

"I stayed by the pump until the water was up to my knees and the cylinders to the pumping engines were under water and stopped," fireman George Geer would write to his brother. "She was so full of water and rolled and pitched so bad I was fearful she would roll under and forget to come up again."

There was a mad scramble among the remaining crew. Some were washed overboard only to be slammed against the side of the ship and scramble back to safety. Or be fished out of the water by boat crews. This was just the beginning because the boats had to be rowed against murderous seas before the men could be hoisted to safety.

Helplessly, survivors watched the Monitor's red emergency lantern flicker and then disappear. It was shortly before 2 a.m., New Year's Eve, when the ironclad slipped beneath the waves and rolled over as it fell to the ocean floor. Sixteen sailors were lost. It would be 14 decades until Navy divers would recover the turret and bring home for burial two of their own who were found there.

Today, the Mariners' Museum in Newport News will offer tours of the conservation area where the turret now rests. There will be a lecture and memorial ceremony.

And the recovered engine room gong will toll for the lost sailors.

___________________________________________________________

The Virginian-Pilot, December 30, 2012

MARINERS' MUSEUM HONORS FALLEN MONITOR SAILORSPermission given by the author Margaret Matray & The Virginian-Pilot to reprint this article & use of photos.

HAMPTON

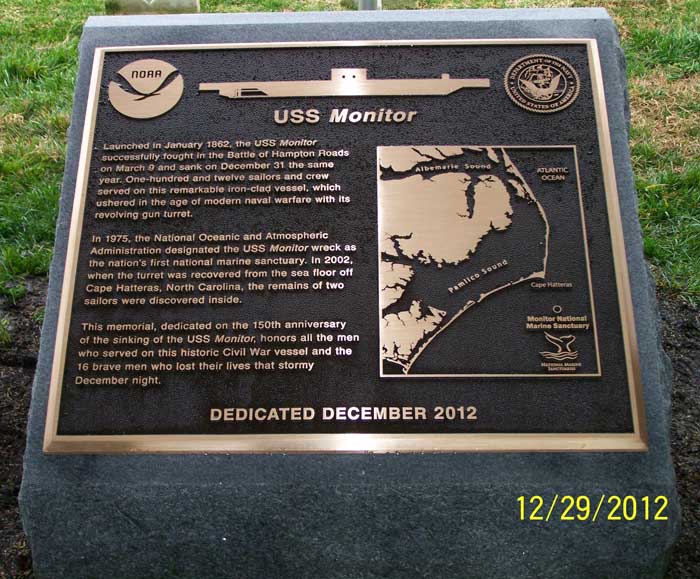

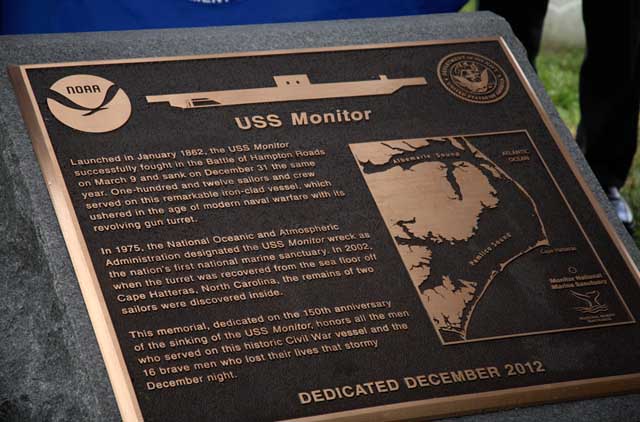

On a plot of grass in Hampton National Cemetery, a stone marker with a metal plaque memorializes 16 men lost at sea a century and a half ago.

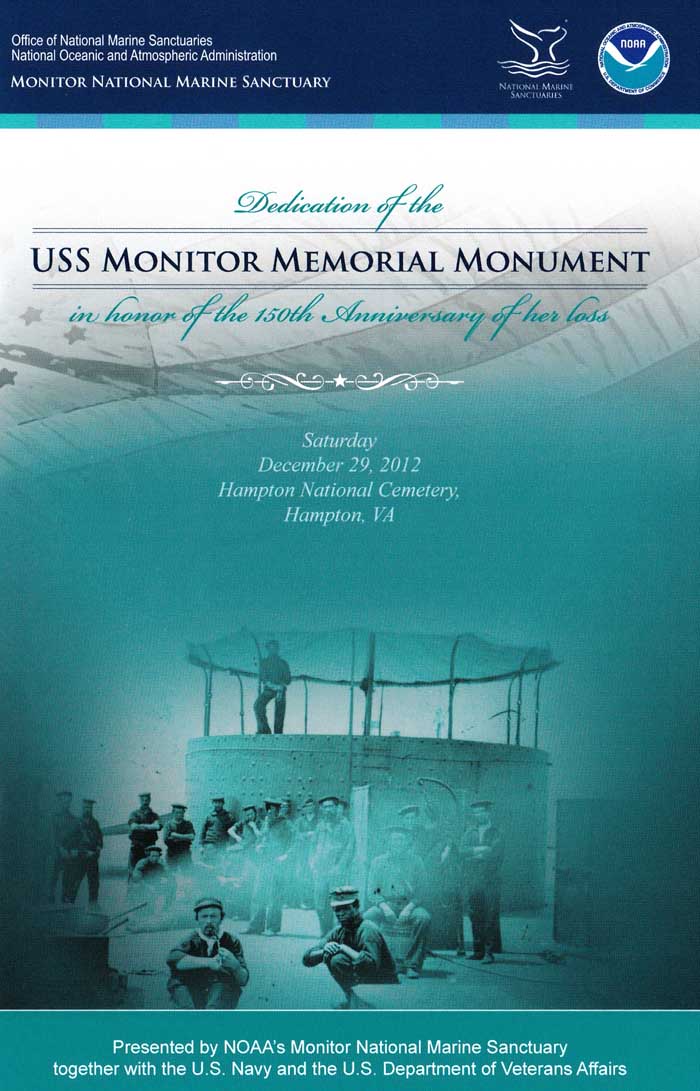

Saturday, a color guard presented its flags. A wreath was placed. A bugler played taps. And the new USS Monitor Memorial was unveiled to recognize the crew that died on the final voyage of the Union ship, which fought the Virginia in the Civil War's Battle of Hampton Roads and ushered in the era of ironclad warships.

Throughout that night, 150 years ago today, 20-foot waves rolled over the Monitor and finally sent the ship to the bottom of the Atlantic Ocean off Cape Hatteras, taking with it 16 officers and sailors.

"Their story is truly one for the ages," Anna Holloway, curator of the USS Monitor Center at the Mariners' Museum in Newport News, told a crowd of 80 gathered for the unveiling.

Under the tow of the Rhode Island, the Monitor left Hampton Roads on Dec. 29, 1862, bound for Beaufort, N.C. The next day, the wind blew heavy, clouds darkened and by evening, a heavy rain fell. Waves began to break over the ship, sometimes hitting hard enough to make its frame tremble.

In the moonlight, crew members could see the waves' white foam gushing toward them.

Then one of the ship's hawsers snapped, whipping the Monitor about. Caulking came undone and water rushed into the engine room. The coal was too wet to keep up steam.

At 10:30 p.m., Capt. John Bankhead ordered the red distress lantern be raised and a half hour later, he called for the Rhode Island to send rescue boats. Shortly after midnight, the Monitor's pumps stopped.

"It is madness to remain here longer.... Let each man save himself," the captain said, according to firsthand accounts.

William Keeler, the ship's assistant paymaster, took off layers of clothing to make it easier to swim. He found a rope and slid down to the deck.

"A huge wave passed over me, tearing me from my footing and bearing me along with it, rolling, tumbling and tossing like the merest speck," he recalled.

The ship's light faded from view at 1:30 a.m. Dec. 31.

For more than a century, the Monitor sat untouched 16 miles off the coast of Cape Hatteras. When the Navy formally abandoned the vessel in the early 1950s, private divers could start looking for the ship, Holloway said.

A team discovered the ironclad in 1973, upside down under 240 feet of water.

The first artifact brought to the surface was the red distress lantern, found in the sand next to the ship's remains.

"It's kind of a neat thing that the last thing the crew reported seeing was the first thing to break the surface in 1977," Holloway told The Virginian-Pilot.

Storms that rolled over the Monitor's wreckage made it clear that more needed to be done to keep the ship from deteriorating, she said. The site became the first National Marine Sanctuary.

By the late '90's and early 2000s, crews had raised the propeller, engine and turret and brought them to the Mariners' Museum, home to the Monitor's artifacts since 1986. Conservators continue to treat pieces of the Monitor with solutions and, in some cases, electrical currents to strip away more than a century of sediments and salt.

The museum has 200 tons of the warship's artifacts and hopes to have all items preserved and on display by 2029, Holloway said.

"The whole idea is to make these things accessible so the story lives on," said David Krop, director of the museum's Monitor Center.

At Saturday's ceremony, it was the stories and lives of the men that were remembered. They were ages 18 to 32, black and white, some from as far away as England and others as close as Virginia, Holloway told the crowd.

"May we never forget the heroic efforts of these men," Capt. Donald Troast, a Navy chaplain, said in a closing prayer.

___________________________________________________________

The Sinking and Loss of the USS Monitor ~ 150 Years Ago on December 31, 1862.

Marcus W. Robbins, History Matters, Blog #24 of December 29, 2012, found on the Norfolk Naval Shipyard website.

The following is a mixture of my own words and personal observations while drawing upon existing postings from both the Naval History & Heritage Command and the National Monitor National Marine Sanctuary websites concerning the USS Monitor sinking, my visit to the Mainers Museum on March 8, 2012, and my attendance today at the Hampton National Cemetery for the dedication of the USS MONITOR MEMORIAL MONUMENT.

USS Monitor, a 987-ton armored turret gunboat, was built at New York to the design of John Ericsson. She was the first of what became a large number of "monitors" in the United States and other navies. Commissioned on 25 February 1862, she soon was underway for Hampton Roads, Virginia. The Monitor arrived there on 9 March, and was immediately sent into action against the Confederate ironclad CSS Virginia, which had sunk and destroyed the USS Cumberland & USS Congress the day before. The resulting battle, the first between iron-armored warships, was a tactical draw. However, Monitor prevented the Virginia from gaining control of Hampton Roads and thus preserved the Federal blockade of the Norfolk area.As I like to provide with each of my writings some obscure lesser known yet direct connection to the old Norfolk Navy Yard, here are a couple of lesser known tidbits of information concerning USS Monitor.

First, tempting as it might have been for Monitor to attack the Gosport Navy Yard before CSS Virginia ever came out, it was deemed too risky to attack for fear of being trapped by a physical blockade once in the narrows of the Southern Branch of the Elizabeth River thus preventing Monitor's escape. Virginia was also able to return to the Gosport drydock for further repairs and alterations after the Battle of Hampton Roads on March 9, 1862, and continued to remain unmolested at home in Gosport due to the same reason. The stalemate continued between the two ships into the spring of 1862, never directly engaging each other again.

Secondly, yet in due time, Monitor did indeed sail down the Elizabeth River, now escorting President Lincoln on the USS Baltimore to observe the Navy Yard in ruins as it smoldered again, this time due to the self-inflicted Confederate torching the day before. The President and his small fleet had just visited the area where Virginia was blown up by her own crew off Craney Island just a few hours prior before sailing past Norfolk and the Gosport Navy Yard the early morning of May 11, 1862. The Monitor most likely turned around and headed north to carry the President back to Washington DC after observing the old stone drydock, the birthplace of the Virginia at the southern extreme of the shipyard.

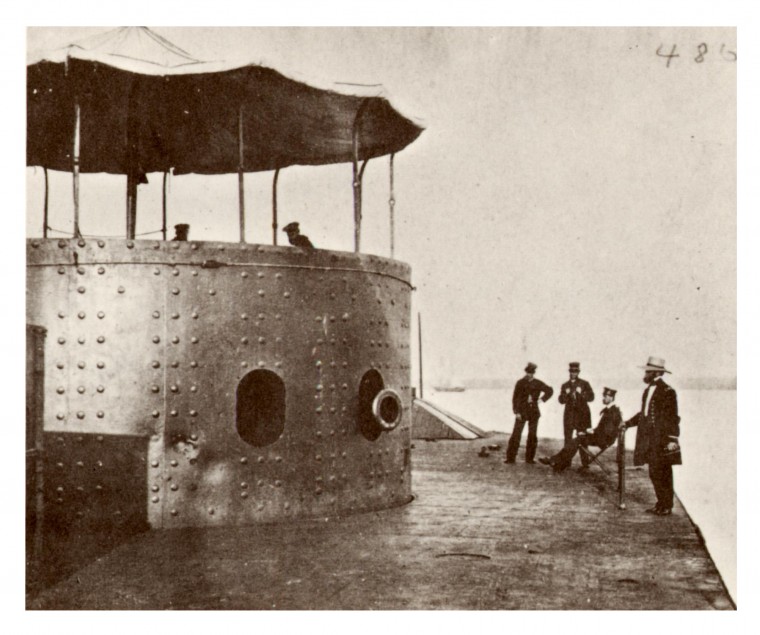

Monitor remained in the Hampton Roads area and in mid-1862 was actively employed along the James River in support of the Army's Peninsular Campaign. It is at this time various photos are taken of Monitor's officers and crew. Photos have a way to preserve and document naval service on a more personal level. Who were these men, what did they look like and how did they live aboard ship? Today is a day of remembrance to Monitor's men.After a hot summer of routine duty in the Hampton Roads area, Monitor badly needed an overhaul. This work, done at the Navy Yard in Washington, DC, fitted the ship with a telescopic smokestack, improved ventilation, davits for handling her boats and a variety of other changes to enhance her fighting power and habitability. She returned to the combat zone in November 1862, remaining in vicinity of Newport News for the rest of that month and nearly through the next.

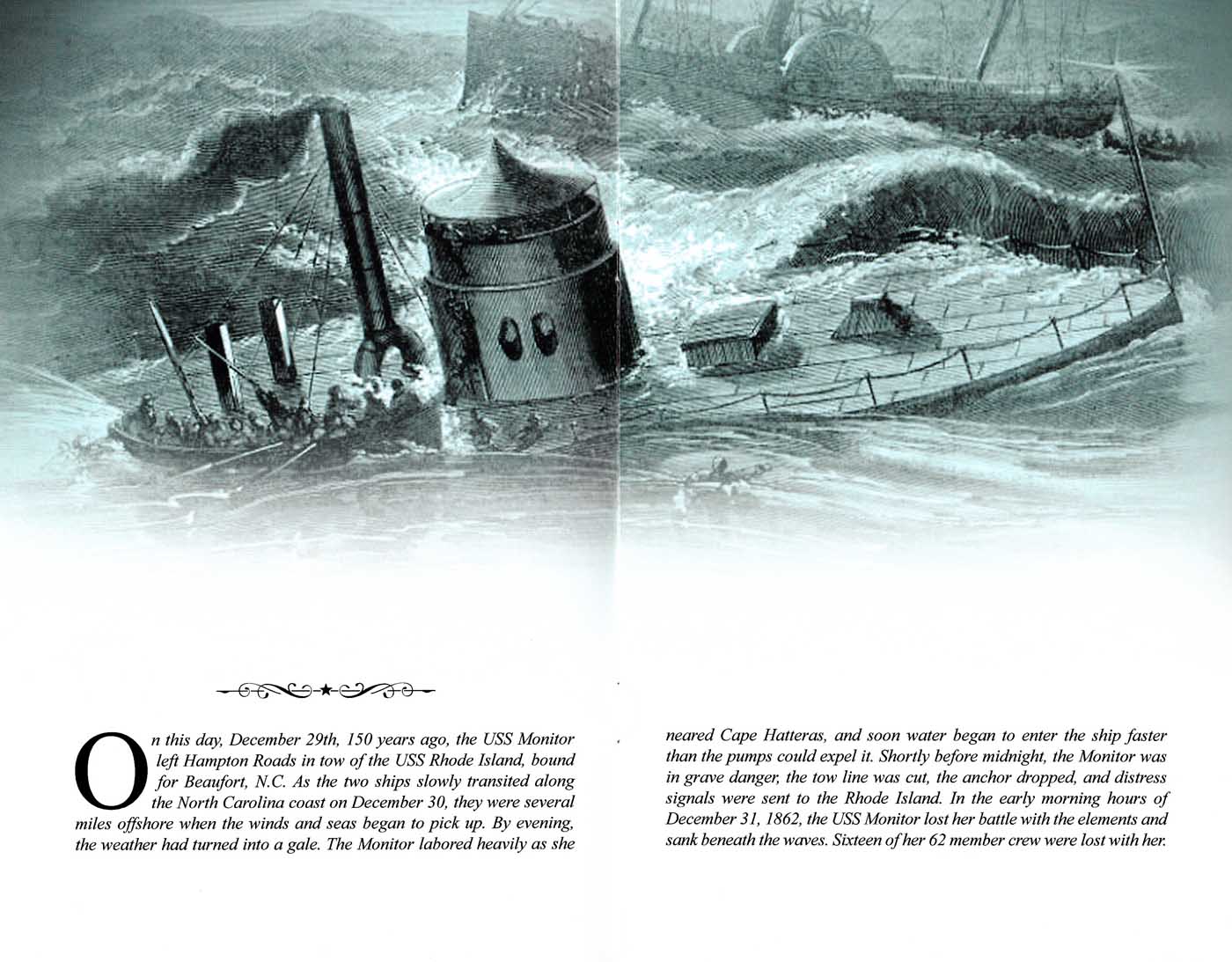

In December, Monitor was ordered south to join the blockading forces off the Carolinas. After preparing for sea, on 29 December she left Hampton Roads in tow of USS Rhode Island, bound for Beaufort, N.C. The weather, expected to be good for the entire voyage, stayed that way into the 30th as the two ships moved slowly along several miles off the North Carolina coast. However, wind and seas picked up during the afternoon and turned to a gale by evening. The Monitor labored heavily as she neared Cape Hatteras, famous for its nasty sea conditions. Water began to enter the ship faster than the pumps could expel it and conditions on board deteriorated dangerously.

Shortly before midnight, it was clear that Monitor was in grave danger. Her steam pressure was fast failing as rising water drowned the boiler fires. The tow line was cut, the anchor dropped, and distress signals were sent to the Rhode Island. Boats managed to remove most of the ironclad's crewmen under extremely difficult conditions, but several men were swept away. Finally, at about 1:30 in the morning of 31 December 1862, the historic Monitor sank. Sixteen of her crew of sixty-two were lost with her.

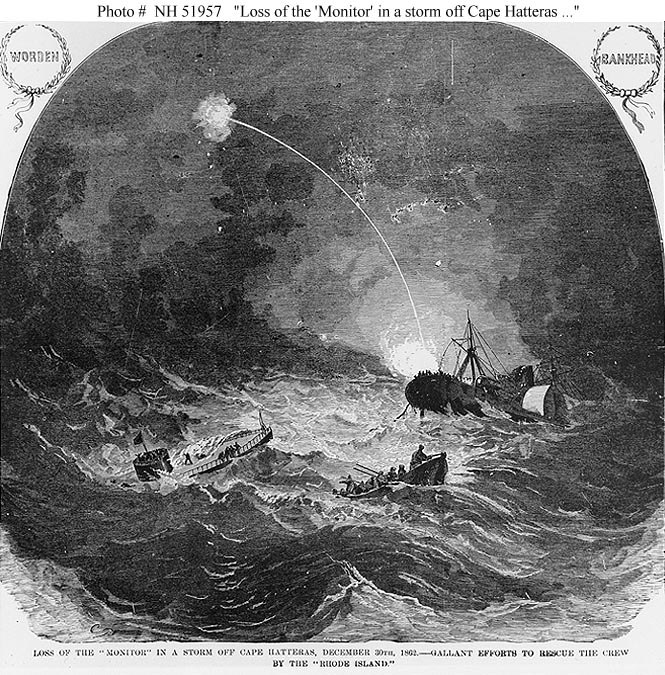

Loss of the "Monitor" in a Storm off Cape Hatteras, December 30th, 1862. – Gallant efforts to rescue the Crew by the "Rhode Island".

(Naval History & Heritage Command image NH 51957)

The above line engraving was published in "The Soldier in Our Civil War", Volume I, page 248. It shows USS Monitor sinking at left with a boat picking up crewmen as USS Rhode Island stands by in the right background firing rockets.

The Monitor shipwreck was discovered in 230 feet of water approximately 16 miles off of Cape Hatteras in 1974. It has been now designated the nation's first national marine sanctuary. In August of 2002 the turret was raised, then taken to its new home at the Mariners Museum in Newport News, Virginia, for long term conservation and display. It is well worth the trip and you will also wish to return again in future years to observe their continuing progress of bringing the USS Monitor back to life.Of those sixteen crew members that perished, two sets of remains were found during the recovery effort. The remains of these two unknown sailors currently reside with the Joint POW/MIA Accounting Command in Hawaii. NOAA is making every effort to identify these sailors and to have them interred at Arlington National Cemetery in 2013.

When I toured the Mariners Museum this year on March 8, 2012, to celebrate the 150th anniversary of the Battle of Hampton Roads, I was privileged to be in the right place at the right time just after opening and before the crowds got there. I was able to view up close the Monitor's famous gold ring as it was taken out of its display case by the staff. It was an honor for me to be within inches of such an iconic historic artifact that day. I will forever realize and appreciate the very personal and yet tragic side to this story, as there were two sets of human remains recovered in the turret. Now it wasn't just about the ship but about the men that sailed, operated and ultimately gave their lives for USS Monitor.

On Saturday, Dec. 29, 2012, NOAA's Office of National Marine Sanctuaries, together with the U.S. Navy and the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, dedicated a memorial to honor the USS Monitor and the memory of the 16 sailors who died that night the Monitor sank. Placed in the Civil War section of Hampton National Cemetery, located on the Hampton University campus, the monument memorializes the iconic vessel and the heroic efforts of the brave men who served their country.

Memorial to honor the USS Monitor and the 16 sailors who died when the ship sank.

(Photo taken by Marcus W. Robbins at dedication ceremony on December 29, 2012)

Wreath to honor the USS Monitor and the 16 sailors who died when the ship sank.

(Photo taken by Marcus W. Robbins at dedication ceremony on December 29, 2012)It is so important now 150 years later to remember both the CSS Virginia and the USS Monitor for each of their unique designs and contributions that changed naval warfare forever. It is equally important for us to pause and remember the men that served upon each ship and even gave their lives because – "history matters".

___________________________________________________________

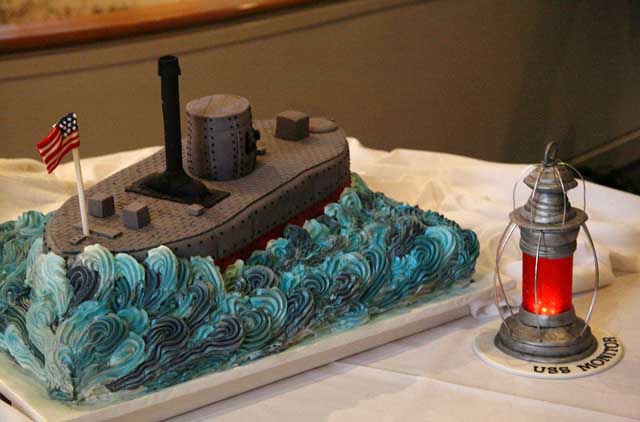

The following photos were taken on December 29, 2012, by staff at the Mariners' Museum and were provided upon special request to the Norfolk Navy Yard website to depict a representative sample of the day's events. Scenes shown are at the Hampton National Cemetery, Hampton, Virginia, where the USS Monitor Memorial was dedicated and the reception afterward at the Mariners' Museum located at Newport News, Virginia. Also shown are a few photos from a special tour afterward in the conservation area that same day to observe the USS Monitor's turret, engine and guns up close.