Transcribed for Sargeant Memorial Room

by patron Donna Bluemink

JOSE DEMAS GARCIA CASTILLANO

Who were executed on Friday the 1st of June, 1821, in the rear

of

the town of Portsmouth, in Virginia, for a most

horrid murder and butchery,

committed on

Together with an

APPENDIX.

Containing their confessions, &c.

Norfolk,

Published by C. Hall,

and sold by most of the

Booksellers in the United States,

June, 1821.

[Page numbers appear in brackets in bold print.]

[ii] DISTRICT OF VIRGINIA, to wit:

BE IT REMEMBERED, That on the second day of June, in the forty-fifth year of the Independence of the United States of America, William G. Lyford, of the said District, hath deposited in this office the title of a book, the right whereof he claims as proprietor, in the words following, to wit:

"An Account of the Apprehension, Trial, Conviction, and Condemnation, of Manuel Philip Garcia, and Jose Demas Garcia Castillano, who were executed on Friday, the 1st of June, 1821, in the rear of the town of Portsmouth, in Virginia, for a most horrid murder and butchery, committed on Peter Lagoardette, in the Borough of Norfolk, on the 20th of March preceding–Together with an Appendix, containing their Confessions, &c."

In conformity to the Act of the Congress of the United States, entitled, "An Act for the encouragement of learning, by securing the copies of Maps, Charts, and Books, to the authors and proprietors of such copies, during the times therein mentioned.

RD. JEFFRIES,

Clerk of the District of Virginia.______

[iii] TO THE PUBLIC.

As it was conceived that considerable interest would be excited at the result of the trials of MANUEL PHILIP GARCIA, and JOSE DEMAS GARCIA CASTILLANO, for the murder of PETER LAGOARDETTE, I came to the conclusion, soon after they were remanded to take their trial before the Superior Court, to possess myself of all the circumstances connected with that horrid affair, and to publish them in a pamphlet form: and to enable me to be as accurate as possible in my narration, I was permitted by the gentlemen having charge of all the papers in any way appertaining to those men, to examine and compile from them such portions as might appear relevant to my purpose. I have endeavored to do so; but yet I may have failed in some inconsiderable instances— for errors are too apt to creep in, through the hurry in getting such a work to the press. The two men being foreigners, (Spaniards) and not acquainted with our languages (one of them at least, and the other but very imperfectly,) their communications were all made in Spanish, badly spelt, and not easily legible—it consequently required time to have them translated with accuracy.

I am indebted to the columns of the "Norfolk and Portsmouth Herald," for the considerable assistance which it has afforded me as the trials of the prisoners progressed. I am indebted to Mr. JAMES HENRY for his repeated visits to the prisoners, to procure for me their confessions, and for the verbal information which he has obtained from them, he being capable of conversing with them freely in their own language: and I am particularly indebted to the officers having charge of the prisoners, for their politeness in affording me at all times the information which they possessed, as well as their other acts of politeness, when a request was made of them.

[iv]

I have hereunto annexed some certificates, the object of which is visible upon the face of them. I do not apprehend that any other publication will be made, purporting to be a Confession of Garcia and Castillano, but I have thought it not amiss to guard against one.

I am the Public's most obedient servant,

W. G. LYFORD.Norfolk, June 2d, 1821.

The following is an extract of the translation of a Note attached to a document,* which was handed to Mr. Henry by Garcia, as he was preparing to ascend the scaffold–it is dated May 30th, 1821, two days before his execution:"I declare, that any other paper which may be published as mine, except one dated the 10th inst.† is false. The only Declaration of mine, and of my ‡ writing, is this, and that of the 10th instant, which is in the hands of Mr. Henry.

(Signed,) MANUEL PHILIP GARCIA."

The following certificate was written on the 28th May:–"I hereby certify, that all the papers which have been written by me for publication, (since my confinement,) are in the hands of Mr. Henry.(Signed,) JOSE DEMAS GARCIA CASTILLANO."

"This is to certify, that I have put into the hands of Mr. WM. G. LYFORD, all the papers and documents of every description that I have ever received from Manuel Philip Garcia and Jose Demas Garcia Castillano, for publication–and that I have never suffered any other person to peruse them; neither have I a copy or a translation of any of them, nor have I in any way promulgated or communicated their contents to any other person. Given under my hand at Norfolk, this second day of June, 1821.

(Signed,) JAMES HENRY."

*Appendix, page 24–† ibid. page 15. ‡ Garcia had probably forgotten his confession before the Mayor on the 28th March, or it being a translation only which he then signed, possibly did not consider it "his writing."

______

ERRATA. –In page 18, 12th line from the bottom, read, the under jaw fell off–the body which, &c.

Page 19, 14th line from the top, dele the s in prisoners." –5th line from the bottom for "ten," read twenty.

Page 20, line 16th from the top, after "that," read which.[5]

AN

ACCOUNT

OF THE

APPREHENSION, TRIAL, CONVICTION, CONDEMNATION, CONFESSION, AND EXECUTION

OF

MANUEL PHILIP GARCIA

AND

JOSE DEMAS GARCIA CASTILLANO,

FOR THE MURDER OF

PETER LAGOARDETTE.ON Tuesday, the 20th of March, about two o'clock, p. m. Josiah Cherry, a police officer, was informed, on coming home to his dinner, that something like a murder must have been committed that morning in Mrs. Hetherington's house, as a considerable noise like scuffling, and screams, had been heard there by some of the neighboring women and children.—The house from which the noise issued was not more than sixty or sixty-five yards back from Cherry's house, and he immediately hurried to it to endeavor to ascertain the cause of the alarm. On coming to the house, he found it secured, and no person apparently in it. Not willing to take upon himself the responsibility of forcing it open, he proceeded immediately to the Mayor for instructions, who authorized him instantly to return and break the house open, which order he accordingly obeyed.

The building in question is a two story wooden house, standing upon columns of bricks about eighteen inches from the ground; its gable ends towards the east and west, with two doors to enter it, one of which is in the west end and the other on the north side. The house is probably about twenty-five feet long and seventeen broad, with two rooms on the lower floor, and two rooms and a passage on the upper floor, the passage up stairs dividing the two rooms. There [6] are no windows, either above or below, on the south side of the house, and the windows on the lower floor have all of them shutters except, one at the east end and nearest the south side—there are four windows at the east end, two of which are above, and of course the others below; and five on the north side, three of them above, and two below—those at the west end it is not material to name; suffice it to say, that in the upper room at the east end of the house, are three windows, which have already been described; and the reason for being thus particular concerning this house, &c. will be manifest before this narrative is completed.—And now for its situation.

The house is a retired one, standing in the fields, about equal distance from Church, Bute, and Cumberland streets, say sixty yards from either, and perhaps about an hundred and twenty yards from Charlotte street. On Church street, in front of Plume's rope walk, but on that side of the street next to the house, are several dwelling houses, all of which are occupied; but between these houses and the house where the murder was committed, are gardens, one of which extends down to within about four feet of the house, where it is terminated by a fence, which forms a yard at the east end of the house—on the south side is a house about forty yards from the house in question; and at the west end a kitchen occupied by an old black woman, and almost adjoining the kitchen westwardly an unoccupied house. Towards the west and north west, the nearest house is probably an hundred and fifty yards, and towards the north is the French Masonic Hall, which is about an hundred yards distant—the space between the house and the streets to the west and north is a common, and being quite flat, in the spring season is apt to be wet, and consequently but little passing over it. The house commands a good view from the rear of those houses on Church street, but cannot be perceived by any person on the street. The tenants of most of them are men whose avocations call them into the more business part of the town, so that from early breakfast they are absent until dinner, the children are some of them at school, and the women, engaged in their domestic offices, seldom have occasion to attend to, or think of, any thing else except matters of their own household.

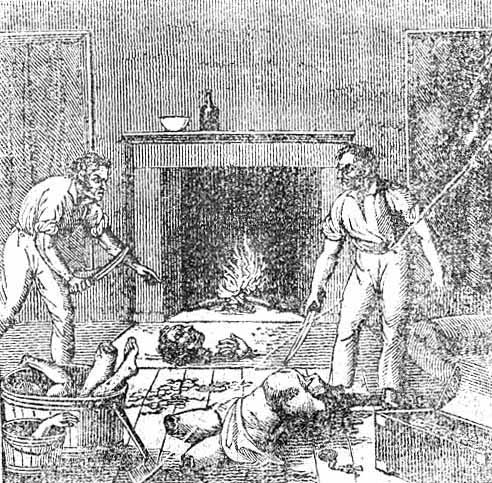

As soon as Cherry opened the house by entering at the window, he proceeded up stairs, (seeing nothing below that was worthy of observation,) and on entering the room at the east end of the house, discovered a spectacle truly horrible and revolting to the feelings of humanity. The trunk of a human being lay extended upon the floor, divested of its head and limbs, and bleeding; on the fire which was [7] burning, he found the head, hands and feet, burnt almost to a cinder; in a tub, the arms and legs, which appeared to have been dissected with the greatest surgical skill; and on the floor, the axe and two butcher knives, all besmeared with blood, with which the diabolical deed had been perpetrated by some hellish murderer or murderers !!!!

The officer having given the alarm, a number of persons of course soon collected, and information being sent to the Coroner of the Borough, an inquest was summoned, who repaired to the house, where, after investigating the matter as well as their slender means would enable them, and sending for and examining such persons as circumstances and chance happened to bring to their minds, they reported the following verdict:—

"Norfolk Borough, to wit—

"Inquisition indented, taken at a house belonging to Mrs. Hetherington, in the fields, not far from Plume's rope walk, in the Borough aforesaid, the twentieth day of March, in the year of our Lord, one thousand eight hundred and twenty-one, in the forty-fifth year of the Commonwealth, before me, George W. Camp, Coroner of the Commonwealth for the said Borough, upon a view of the body of a white man, (unknown to the Jury,) then and there lying dead, and upon the oaths of Thomas B. Seymour, Alexander Jordan, Henry H. Newsum, Thomas R. Walker, Thomas B. Dixon, John S. Widgen, Charles Spratley, Francis Butt, Michael S. Wilson, William S. Keeling, William Bolsom, and John Hester, good and lawful men of the said Borough, who being sworn and charged diligently to inquire on behalf of the said Commonwealth, when, where, and after what, manner, the said person came to his death, upon their oaths do say, that some person or persons to them unknown, not having the fear of God before his or their eyes, but being moved and instigated by the Devil, did, some time between the hours of twelve o'clock of yesterday and twelve o'clock of this day, feloniously and with malice aforethought, make an attack upon the said deceased, with an axe and two knives, with which said weapons the said deceased was murdered, supposed by a blow on the head with the said axe, given by the person or persons unknown as aforesaid; who, having deprived the said deceased of life, did, with the said knives, cut off his head, arms and legs, which were inhumanly thrown into a fire in the room where the murder was committed, and the head so much burnt as to render it impossible to distinguish the features of the deceased–and [8] so the Jury do say, that the said deceased was wilfully, deliberately, and maliciously murdered by the person or persons to the Jury unknown. In testimony, &c."

Signed by all the members of the inquest.

The murderers had taken the precaution, previous to dissecting their victim, to nail up two blankets to the windows in the room where he lay, viz. one at the end (there having been a curtain at the other end window already) and the other at the side of the room. There was no article of furniture in the house except a mattress, which had marks of blood upon it, two or three blankets, and a portmanteau—the trunk was found open, with a number of gold and silver watches in it, several articles of jewelry and other valuables, and an elegant gold patent lever watch lay upon the floor. Several articles of clothing were also found in the trunk, some of which were stained with blood—some of the shirts and waistcoats were marked P. L. and some of them M. P. G.—A Masonic Diploma was also found in the trunk, issued by the Grand Lodge of Maryland, dated at the city of Baltimore, December 21, 1820, and filled up with the name of Peter Lagoardette, whose name was signed in the usual way in the margin.—A coffin was prepared for the deceased, his remains interred, the articles found in the house taken charge of by the Coroner, and the house secured. Previous to this time, however, the circumstance had become so notorious all over town, that thousands of persons had collected to see the horrible sight, or to hear the particulars, if they could, of the murder—but in the latter they were completely disappointed.

The anxiety, however, to learn from some one, who might probably be the perpetrators of the dreadful deed, was not to be easily allayed—every inquiry was made, and numbers were describing sane suspicious looking person that they had recently seen. Mr. Holt, the Mayor, visited in person several of the houses in the vicinity, and left no effort untried to ferret out the murderers—he had a number of persons brought before him, in the court-house, at night, but could collect no further information, than, that the house had been rented of Mrs. Hetherington, about three weeks before, by a Frenchman, whose name no one knew, but that he went by that of Dett—Mrs. Hetherington was in the country herself, so that nothing could be learned satisfactorily who the tenants were, and Dett had never been seen in company with any one at the house; but on the night previous was seen at a house of ill fame with a person who ap-[9] peared to be a Spaniard. Thus terminated the inquiries of the day and night, with no prospect of succeeding in a discovery of the fugitives.

But the account of such an abominable and unnatural murder waited not the tardy progress of the swiftest wings to convey it abroad, it went with the quickness of the lightning's flash, and before night had paid her accustomed visit, was circulated for miles in the country, and in various directions.—On the next morning, (Wednesday,) an extensive fire broke out in our neighboring town of Portsmouth, and so great was the light of it, that people from the country, for some miles around, had collected in the early part of the day to ascertain its cause, extent of the damage, &c. An idea was entertained by numbers that the murderer or murderers might possibly have also been the incendiary or incendiaries.—The Mayor was vigilant all the day, and collected various testimony from different persons; and through the course of his inquiries, discovered by a drayman, (a colored man,) that on the Friday evening preceding, he had taken a trunk and some other articles on his dray, from on board the steam boat Virginia, which had arrived that evening from Baltimore, and carried them to the house where the murder had been committed. The drayman stated, that he was employed by a small man, apparently a Frenchman, and that when they reached the house, the man knocked at the door, and a swarthy looking man opened it, and the articles were carried in. The tenant of the house was in an undress, with a night cap on, and appeared as if just risen from his bed, although it was not then sun-down.—This small discovery to some thing like a clue to a fuller one, having been made, recourse was had to the list of passengers who had come down in the steam-boat from Baltimore, and they all could be accounted for except P. Lawrence and Jose Garcia.—It was also understood from some gentlemen in the course of the day, that two very suspicious looking men, apparently Spaniards, from the contour of their faces, were seen about two or three o'clock in the afternoon of the preceding day, in the fields, in the full view of the house where the murder was committed, and that they were walking out of town in the direction of Princess Ann. They were represented as being dressed in fashionable great coats, of a liver or brown color.

Among those persons who came to Norfolk on Wednesday morning, to see where the fire was raging, (for it broke out about three o'clock,) and what was its extent, was Capt. Jacob Shuster, a farmer, who lives on Tanner's creek, at Bowdoin's ferry, [10] about four miles from Norfolk. Capt. Shuster, during his stay in town, which was the principal part of the day, heard the various reports that were circulating respecting the murder the day previous; and when he returned in the evening, Mrs. Shuster informed him that two men, (apparently foreigners,) had crossed the ferry the forepart of the day, and gone towards Sewell's Point. [It may be proper here to mention, that this is not a regular ferry at this time, a boat being kept upon the creek merely for the purpose of conveying the neighbors across; hence something like surprise was expressed by Mrs. S. that two strangers should have found their way there, and wish to cross.] Mrs. Shuster further informed her husband, that one of the men discovered much alarm while there; and that Mr. Jordan, their neighbor, had come there just after the two men had got into the boat, and informed her of the murder that had been committed in Norfolk the preceding day, and that he strongly suspected those two men to have been the murderers; he stated the reasons upon which his belief was founded, and regretted that she had suffered them to cross—the reasons which Mr. Jordan assigned, will be introduced in his evidence. On hearing the foregoing, Capt. Shuster immediately returned to Norfolk, where he arrived about nine o'clock at night, in the rain, (for it had been raining occasionally, or a fine mist falling, all day,) and communicated the above intelligence to the Mayor.—Capt. S. then returned home.

The Mayor immediately convened the town watch, and authorized there to raise a sufficient number to form two squads, and go in pursuit of the two men described by Capt. Shuster; but no horses could be procured sooner than day-light, and they were compelled to defer starting until that period.

On his way home, Capt. Shuster had come to the determination, if he could collect a few friends, to start in pursuit of the supposed murderers; and having succeeded in his first object, after returning home the second time, sent back again to Norfolk, between ten and eleven o'clock, to procure additional and more trusty arms; as soon as the messenger returned he started with his party for Tanner's creek cross-roads, intending from thence to proceed to Sewell's Point. The party consisted of Jacob Shuster, John Wilson, Robert Addison, James Dameron, and William Knight. The party rode on to Sewell's Point, and about sunrise, on a small point of land projecting out from the main point, called Lavender's Point, discovered the two men [11] who were the object of their pursuit. Mr. Wilson rode up to them, being in advance of the party, and inquired, "What they were doing there?" Their answer was, "Fransch frigat," pointing towards Hampton Roads, as if it were their object to see or get on board the French corvette La Tarn, which had sailed from the Roads on the Monday morning preceding, which circumstance had been published in the Norfolk papers, and which was also a matter of general notoriety in the town. Mr. W. told them it was necessary that they should unbutton their coats, that he might see if they were armed, which they did, but none were found upon them; and the other persons of the party having come up, they told them that they must go with them to Norfolk; they made no objection, but replied or signified, "we give up," The party then brought them on to Capt. Shuster's house, and Capt. S. taking them in a chair, sat himself in the foot of it, and under the escort of their guard brought them to Norfolk.

The intelligence of their having been taken reached town an hour or two before the prisoners; and so great was the anxiety of the people, and such the excitement which had been produced, that Church street was thronged with spectators on either side for a considerable distance beyond Fort Barbour, all eager to get a sight of the supposed murderers, or to learn the circumstances of their capture. At twelve o'clock the prisoners were led into court, followed by the crowd, which in a little time collected in so large a mass, that every avenue to the court-house, was completely blocked up, and the efforts of the attending officer, to clear the bar were totally unavailing. The prisoners were therefore placed immediately below the Bench, where the witnesses also took their places.

It is not deemed necessary here to detail the evidence of the witnesses called upon to testify against the prisoners, as it will come more properly in the proceedings of the commonwealth against them in the superior court; but the substance is indispensable, that the reader may know the grounds upon which they were committed for further examination.

Mrs. Hetherington, the proprietress of the house in which the diabolical deed had been committed, deposed, that a person, (supposed to have been the deceased) applied to her for her house and took it on the second instant (March;) he was a foreigner, supposed him to be a Frenchman; stated that he had no family, but expected his brother shortly from Baltimore, on whose account he had taken the [12] house—she never inquired his name. He was genteel in his appearance and deportment, rather under the middle stature, dark complexion; a little pitted with the small pox, black whiskers, and appeared to be about twenty-six or twenty-seven years of age. She knew nothing of the two prisoners, having been absent in the country from a day or two after she had rented her house until after the murder was committed.

But there were witnesses who came forward, when they saw the prisoners, who deposed that they had seen them before. The carpenter who put the handle to the axe deposed, that the axe was brought to him by two men very much resembling the prisoners, on the Friday preceding, one of whom told him in broken English what he wished—and an apprentice to this same carpenter deposed positively as to the identity of the prisoners; he thought it was on Friday afternoon, but was certain as to their persons; one of them, the eldest, asked to have "one," understood him to say or mean, helve, because he pointed to the eye of the axe—they said they would call again when it was done. They then lighted their segars (for there was a fire in the shop) and went out. Some short time after they returned again, paid twenty-five cents for the helve, bade "good evening," and went away. Another witness, a little girl, only ten years old, deposed to the fact of seeing the prisoners often at the fatal house, for she had been induced sometimes to go there, as her mother lived upon the adjoining lot, and as the Frenchman, (meaning the deceased,) had told her if she would come he would give her apples, nuts, &c. and she had accepted the invitation. On the morning of the murder, she being out in the rear of her mother's house, heard a noise like people in a scuffle, and a scream from within, something like that of murder. She was very much alarmed, and cried with fear, her mother being from home.

'The court deemed the above testimony sufficient to justify them in committing the prisoners for a further examination, and they were committed accordingly. After being carried to prison their persons were searched, and blood was discovered upon the body of one of their shirts, and upon the sleeve of the other—one of the shirts was marked P. L.— a paper, discolored with blood, dropped from the hat of one of them—one of them also had his thumb much wounded from an apparent bite of very blunt teeth, and the other one had a fresh cut in the forehead over the eye.

The circumstances attending the apprehension and examination of the prisoners were all published the next day in the "Norfolk [13] Herald," and the consequence was, that many other circumstances attending the murder and fixing the guilt upon the prisoners were developed by the appearance of new witnesses against them; who, although they could have made the same disclosures and stated the same facts previously, did not know who were the persons they were thus to implicate until they had seen them, and the recollection of transactions with them had brought them to their knowledge.

On the 27th March a letter was received by a gentleman in Norfolk from his correspondent in Baltimore, stating the disappearance of a Spaniard from that city named Manual Philip Garcia, "who, from circumstances, it was supposed had been enticed into the country, and there murdered by the same men confined in the jail at Norfolk for the murder of Lagoardette. Independent of Garcia's being missing, it is ascertained that one of the prisoners whose proper name is Jose Demas Garcia Castillano, was seen about a fortnight previous to take a trunk, mattress, &c. out of Garcia's house, and carry it away." Thus much for the letter—now for a solution of the mystery of the missing man from Baltimore.

By a reference to the way-bill of the steam-boat Virginia, and from the testimony of Mr. Pennington who kept the accounts, &c. on board the boat, it appeared that the murdered man, whose name was entered on the way-bill, Lawrence, arrived at Norfolk on the 2d of March, (the day on which he took the house from Mrs. Hetherington,) from Baltimore, and of the 10th of the same month the two prisoners arrived, also from Baltimore, in the same boat, under the names of Jose Garcia and Juan Gomez: on the Monday following (the 12th,) it was ascertained that Lawrence and Jose Garcia returned to Baltimore, the latter with the key of the house occupied by Juan Gomez, [See Appendix A.] with instructions to bring down a trunk, mattress, &c. belonging to him—[this Juan Gomez, in Norfolk, it will now be readily perceived, was the missing Manuel Philip Garcia in Baltimore]—Lawrence and Jose Garcia (still assuming the same names) arrived at Norfolk again on the evening of Friday the 16th March from Baltimore, and the former immediately took a dray and conveyed his baggage to the house he had rented, as has been before stated by the drayman.

The day fixed upon by the Court for a further examination of the prisoners, was the thirtieth March—and scarcely a day passed that the police officers did not bring forward to the Mayor some new and stronger proof of the villainous pursuits of the prisoners, and, it was [14] not doubted, of the deceased. A great variety of keys, small files, saws, chisels, brass wire, materials for brazing, &c. were found concealed between the plastering and weatherboarding, in the house where they had resided, and the keys so constructed, that the parts calculated to fit the wards of the lock, could be moved at pleasure, and suited to almost any large lock—one key in particular was found, which opened three different locks on three valuable stores, and no doubt could have opened others with the same facility, if they had been tried:—It has been omitted before, but not too late to mention now, that a number of small tools were found in the trunk with the other articles, in the room where the murder was committed.

A communication had been made to gentlemen in Savannah and Charleston, immediately after the first examination of the prisoners, describing, and asking for information concerning them. To the communication to Savannah, the reply was, that "a man named Jose Garcia, who was one of the crew of the General Ramirez, was lodged in jail there on the 7th July, 1820, discharged on the 18th of the same month;" nothing farther as said. The reply from Charleston, dated 30th March, was, that there was "no doubt that the men who had committed the murder in Norfolk were the same who had been repeatedly before the Charleston courts of justice, but that they had generally the address to get off with some slight punishment by way of confinement in jail, for the want of sufficient evidence to convict them;" and concluded by observing, that "it was not more than six weeks since they left Charleston, under the names Garcia and Gomez."

On the 28th, it having been signified to the Mayor, that the prisoner, who had hitherto assumed the name of Gomez, but whose name was now ascertained to be Manuel Philip Garcia, wished to make a confession of the murder; orders were given that he be brought from jail, into the Mayor's office, unshackled and unconfined. A confession was accordingly made by the prisoner, of his own voluntary will and accord, through the medium of an interpreter, to the Mayor and the attorney for the commonwealth; and after being reduced to writing, was subscribed by him. The confession was not sworn to, neither did the court think proper to make any use of it. [It will be found in the appendix marked A.]

On the 30th March, the court convened for the further examination of witnesses against the prisoners Castillano and Garcia—Cas- [15] tillano was first put to the bar. Witnesses were examined, a part of whose testimony has already been given on the commitment of the prisoners, and the subsequent was introduced as establishing that testimony, and confirming the guilt of the prisoners.

William Pennington, sworn.—Belongs to, and keeps the accounts of, the steam boat Virginia; the prisoner, in company with Garcia, and a Frenchman who signed his name P. Lawrence, had made several trips up and down in the steam-boat Virginia, which plies between Norfolk and Baltimore—at one time last fall they all came to Norfolk together, and deposited at the bar of the boat a watch for the payment of their passage. The Frenchman came alone to Norfolk on the 2d of March; the two Spaniards (the prisoner and Garcia) came down on the 10th—on the 12th, the prisoner and the Frenchman returned to Baltimore—and on the 16th, the same two came back to Norfolk.

Capt. James Brown, and James Weaver, the engineer, both of the steamboat Virginia, deposed to the above.

Other witnesses were introduced, who proved the intimacy of the three persons.

Mr. Glenn, sworn.—Stated that Frenchman who said his name was Lawrence, came to his house from the steam-boat Virginia on the 2d March, as a boarder, and went away on the 4th.

C. Branda, J. Morrison, and J. Sounalet, sworn.—Had viewed the Spaniards taken up on suspicion of murder, know them to have visited their shops with a Frenchman who acted as interpreter—had sold them jewelry in November last, and at other times—had seen them together between the 16th and 19th March.

John Victoir, sworn—Knew the Frenchman—had frequented his shop; gave him the handkerchief marked with Miss ____'s name, found in the trunk near the dead body.

Clara ____, who keeps the brick-house, sworn.—Had a dance on the night of the 19th, the Frenchman was there, but did not dance; remained some time—left the house with Nicolas Beauclerc—has not seen him since.

Nicholas Beauclerc, sworn.–Has no knowledge of the Spaniards; was intimate with the Frenchman; met with him at a dance at the brick-house on Monday night, 19th March; it was eight o'clock; Frenchman did not dance, staid some time conversing with him; said he was from Bayonne, and called himself Dett; mentioned that that he had rented a room for cheapness near the Baths, and that he was going that night to Mrs. ____'s to offer her a small gold [16] watch, chain and seals, for forty dollars; shewed it to him; knows it to be the same found in the trunk near the body the next day. Witness walked with him to Mrs. ____'s but knows not whether the watch was offered, cannot say whether he staid all night, or what became of him afterwards.

Ann Armistead, sworn.—Has seen the Frenchman, but does not know his name—he came to their house on Monday night, 19th inst. with Nicolas Beauclerc, about eight o'clock, and quitted it again about nine, Beauclerc going out with him—heard the former say to the latter, on their way out of the house, (they not seeing her, as she was near the stairs), that he was going to a frolic in the river Styx; (a nick-name for a part of Union street) this was the last she saw of him—knows nothing of the watch, or where he usually lodged.

Elizabeth Rose, sworn.—Has been to see the two Spaniards in prison; is positive they are the two persons, who in company with a well dressed small man that appeared to be a Frenchman, called at her shop near the brick-house, on Friday night., 16th inst. to inquire who lived at the brick-house; said they wanted to go there, and walked away in that direction. The Frenchman wore such a great coat as the one found in the trunk near the body.

Green Erskine, sworn.—Sold a tub to one of the Spaniards on the 17th; does not know if it was the one found near the body.

David Etheridge, sworn.—Works with Mr. Delany, a tinner; sold the tin bucket, he saw near the body, to the Spaniards, on the 17th inst. knows its make perfectly.

P. Bellet, sworn.—Lives with D'Anfossy & Duperu; have a large quantity of axes with the stamps, and of the figure and size, of the one found near the body—does not know the Spaniards, and has no knowledge of having sold them an axe.

William Gleeson, sworn.—Is an apprentice to Mr. Vaughan; knows the two Spaniards shewn him, are the persons who came to the shop on Friday 16th inst. with an axe to be helved; that he was present when Mr. Vaughan received it, and made and put in the handle; that the Spaniards in the mean time each lighted a segar and walked away, and when the helve was put in the axe, they returned and took it away with them.

Several other witnesses were examined, and among them were some whose testimony was equally strong or stronger against the prisoners than any here given; but it will come better before the reader to introduce it at the trial before the Superiour Court.—The court unanimously decided, that the prisoners should be remanded [17] for a final trial at the approaching term of the Superior Court for Norfolk County, which would commence its session on the 9th April.

On account of the very inclement weather on Monday the 9th April, and in consequence of the delicate health of the Judge, the court did not convene until Tuesday the 10th, when the proceedings were opened by an able and comprehensive charge from Judge PARKER to the grand jury.—The indictment charged both the prisoners as principals and accessories in and to the murder; and that the murder had been committed by Manuel Philip Garcia and Joseph Garcia, alias Demar Joseph Garcia Castillano, otherwise called Goner or Gomez, on the body of Peter Lagoardette, otherwise called Lawrence, otherwise called Tade, on the 20th March, in the Borough of Norfolk, by an axe, with a blow upon the head, or with a knife or knives, by cutting off the head a little below the chin. The grand jury had no difficulty in soon finding a true bill against the prisoners, and the next day, (Wednesday the 11th April,) Joseph Garcia, alias Demar Joseph Garcia Castillano, otherwise called Gomer or Gomez, was brought into court and put upon his trial.

The court was opened about 11 o'clock; and the house so crowded in every part of it with spectators, so great was the anxiety to see and hear, that it appeared like a convention of the whole county and borough of Norfolk. The prisoner was placed at the bar, and directed to plead to the indictment, the purport of which was explained to him by an interpreter who had been sworn for the purpose, as he pretended to be unacquainted with our language; and he accordingly pleaded “not guilty.” The usual formalities having been gone through with, such as asking the prisoner how he would be tried, &c, and informing him of the liberty he could take in challenging jurors &c. all of which was communicated to him by the interpreter, M. Alessi. The prisoner challenged but four of the jurors; the names of those impaneled were W. F. Hunter, G. White, J. Capron, H. Allmand, Jr., R. Hatton, J. W. Hall, T. Moran, J. Ford, Jr., S. W. Hopper, J. B. Butt, O. S. Dameron, and N Berry.

JAMES NIMMO, Esq. the attorney for the commonwealth, was assisted by Gen. ROBERT B. TAYLOR, who had volunteered his services, (Mr. N's health being inadequate to the arduous duties of the prosecution,) and WILLIAM MAXWELL and ALBERT ALLMAND, Esqrs. appeared as counsel for the prisoner.

The court were about to proceed with the examination of the witnesses, when Mr. Nimmo stated to the court the situation in [18] which he stood with regard to the other prisoner, Manuel Philip Garcia, who perhaps, under an impression that it might benefit his own cause, had voluntarily offered to make a confession of the facts relative to the murder: and that, although it was upon the express assurance on his (the prosecutor's) part that no pledge could be given, that would be of any avail whatever, that a confession had been made; yet, least the unfortunate man might cherish hopes founded on a delusive idea of the existence of such a pledge, he prayed the court to decide on the course proper to be pursued. He had himself never doubted the sufficiency of the evidence already existing, but had not felt himself not at liberty to hear any disclosure which either of the prisoners might think proper, of their own accord, to make, although it might not be necessary to use it in evidence. Having repeated that he was perfectly satisfied to rest the prosecution entirely upon the evidence of the witnesses, it was decided that the confession should not be admitted into court.

Josiah Cherry, a police officer, was the first witness sworn.—The witness stated that he had been called on by Mrs. Lester, about two o'clock, on Tuesday afternoon, the twentieth March, and informed that some person was dead in the house, (meaning Mrs. Hetherington's house) and requesting him to go into it.—Witness went to the house and found it fast, hastened to the mayor for authority to open it, who accordingly granted it.—Witness returned at a quarter past two o'clock, and entered through a window; on ascending the stairs, and entering a room on the second floor, found a person dead, head cut off and in the fire; the arms cut off at the shoulders and at the elbows, and the legs off at the knees; the limbs were placed in a tub and tin kettle which had water in them— the feet and hands were in the fire; on turning over the head to get it out of the fire the under jaw fell off the body—which was yet bleeding, appeared to have been washed; a bloody axe with a new handle in it was lying on the floor, and two bloody knives near the body; the blood was perfectly fresh; has no doubt but the murder was effected by these instruments—the wall was bespattered with blood, and the floor, which was bloody, had been partially washed.— Witness had never been in that house before; lives from seventy-five to eighty yards from it—on entering it, found that the door had been fastened by a lock and the key taken out; the window shutters were closed below, and blankets were hung before the windows up stairs—found the body in the room next to the garden, which lies between the house and Church street, and in view of [19] the witness' residence—several other houses were also near, from which a view could be had of what was transacted in the house where the murder was committed—there is no window on the side of the house next the kitchen.—Witness further stated, that an open trunk was in the room with the dead body, filled with men's wearing apparel, some of which was bloody, and a parcel of watches and jewelry—clothes were also scattered on the floor, and a mattress in one corner of the room with blood scattered on it.

William Vaughan, sworn.—On Friday before the murder was committed, came to his shop two Spaniards to get a helve put to an axe, for which they paid twenty-five cents; prisoner at the bar was one of the persons —knows the axe now presented to be the one he put the helve in.—(Cross examined)—To the best of his knowledge believes the prisoners at the bar to be one of the persons who came with the axe, knows him by his form, clothing, complexion, &c.—it was on a Friday, to the best of his recollection, they applied for the helve, one only of whom spoke, which was in broken English—is positive the prisoner is not the one who spoke. (To a question by the court)—Is not positive that the word “helve” was made use of, thinks if it had been he should have recollected it, but they made him understand by pointing to another.

William Gleeson, (apprentice to Mr. Vaughan,) sworn.—Is confident the prisoner is one who came with another on Friday before the murder for an axe-helve; prisoner said little or nothing, but went away with the other person, they afterwards returned, thinks between two and three o'clock, went to the fire which was in the shop, warmed their hands, lighted their segars, took the axe, paid twenty-five cents, said “good evening, sir,” and went away—saw the same two persons next day, and recognized them immediately —knows the axe now presented to be the one helved at their shop, and that it is the same helve—cannot say whether the word helve was made use of by the persons applying with the axe, but thinks it was, at all events they made them understand by pointing—is positive the prisoner present is not the one who entered into conversation on the subject of the helve.

William Allyn, sworn.—Lives at J. T. Allyn's—had a dozen knives in the store in a package, sold two of them about ten days previous to two foreigners; cannot say that the prisoner at the bar was one of them—one of them spoke broken English, the other said nothing.—When they first came into the store and asked for knives, witness shewed them riggers' knives, and they not appearing to [20] please, shewed them the kind of these, (holding up one of the knives which had been found near the body of the deceased,) denominated in the invoice, "bread knives," they inquired the price, paid for them without saying any thing further, and walked out—thinks he could not have recognized them an hour afterwards. The two knives present are of the same stamp and correspond exactly with the remaining ten in the store. [The knives produced and denominated "bread knives," were about a foot in length; the blade wide, terminating at the point sharp, something like a butcher's knife, and about eight or nine inches in length—indeed they had every appearance of a butcher's knife.]

Mary Lester, (a very sensible little girl, only nine and a half years of age, after being examined by the Judge touching the importance of an oath and the offence of stating things falsely, and having satisfactorily answered to the inquiry, if she knew the consequence of relating that was not true,) sworn.—Had been to school on Tuesday, the day the murder was committed, and when she came home, was told of a noise that had been heard in the house, (meaning, where the murder was committed;) run out and got upon the fence, (it was about one o'clock, according to a calculation made between the coming out and going in of the school) and saw two men, the prisoner at the bar was one of them, come out of the house, and the prisoner locked the door, then kicked it with his foot to see it was fast—prisoner looked the witness in the face while he was locking the door, and then both of them walked towards the fields from the witness—had seen the two men often with the Frenchman, but had not seen them that morning—Had seen them several times come out of the house with the Frenchman, but then the Frenchman always locked the door and then kicked it to see if it was fast. [The little witness further stated, that on hearing that a murder had been committed in the house, she had gone out and got upon the fence to watch the house, to see who come out of it; giving the court and jury to understand, that by this plan she would be enabled to know who of the three was murdered; and when she saw the two Spaniards come out she concluded of course that the Frenchman was the one who was dead.]

Elizabeth Lester, another little girl about twelve years old, sworn.—Had often played about the house of "Peter Ladette," (as she called the supposed deceased;) he had often invited her to the house to get apples and nuts; had seen the prisoner and an- [21] other person at the house, but had never said any thing to them—had often seen the prisoner and his companion, but did not see them together the day the murder was committed—witness went once to the house to get an apple from Ladette, but the prisoner and another one came in and she went out. On the day of the murder, between nine and ten o'clock in the morning, witness was in the garden playing with some other little children, when she heard a noise in the house, and the screams of some one in distress, and a struggling—went lower down the garden; the scream appeared like a faint cry of murder, saw soon after a person (not the prisoner) come to the windows and put a blanket up before it.—After a little while the noise ceased and she could see nothing, the window shutters all being closed—did not see the prisoner at all, and saw no person come out of the house.—Witness, with the other children, ran home crying, because she was scared, and her mother was from home—could see no man to tell what she had seen and heard.—[After some time her mother returned home, and she related to her the particulars as stated to the Court and Jury, and her mother went and informed a constable.]

Margaret Madden, a little girl about ten or eleven years old, sworn. —Confirms the testimony of Mary Lester.

Henry Roberts, a boy about eleven or twelve years of age, sworn.—On the morning of the murder, about ten o'clock, being about ten yards from the house, on the side towards the French Lodge, heard “a lick,” and screams in the house—after a little the noise stopped—saw no person come out or go into the house—never saw the prisoner in the house at all—saw a blanket at the window at the side of the house up stairs after the noise had ceased.—Witness did not stop, but proceeded from the house about his business.

Ann Barret, sworn.—Between nine and ten o'clock, on the morning of the twentieth of March, heard screams for five or ten minutes in the house in the rear of hers, belonging to Mrs. Hetherington, went to the door and heard another faint scream—saw a man with a dark complexion, pacing the lower room in his shirt sleeves, having white pantaloons on—he came to the window several times, and every time would place his eyes upon witness—appeared to be much agitated—his hair was cut short, and could perceive that he had large whiskers—prisoner at the bar, from his size and figure, appears to be the person.—The blanket was put up at, the window after witness had heard the noise—the noise was like a person strangling. The last time the person left the window saw [22] him roll up his shirt sleeve with his left hand. There had been a curtain at the upper window in the end of the house nearest to witness' house, ever since it had been occupied by the late tenants.

Sophia Lester, (mother of Elizabeth and Mary Lester) sworn.— Had been from home all the morning, and until between one and two o'clock; on her return, was informed by her children of the noise they had heard in the house where the Frenchman lived; went into the garden, but heard no noise; saw, however, a blanket hanging up at the window—went immediately to Cherry and Roberts, (two constables) to tell them what had happened.—[In answer to a question by the prosecutor,] had brought her children up in religious habits, and had always endeavoured to instill into their minds the importance of confining themselves to the truth under all circumstances.

John O'Neil, sworn.—Keeps a tailor's shop on Main street; a Frenchman had applied to him some short time previous to repair a coat, which he then wore, but which he took away with him again without getting the work done; the coat found near the deceased in the room where the murder was committed, twentieth of March, was the same coat; knows it by a rent in the black silk lining near one of the pockets—had applied to witness previously to make a pair of pantaloons for him, and when his measure was taken, wrote Lawrence on it, which he gave witness to understand was his name—witness made the pantaloons, they are the same which one of time Spaniards had on when brought to town after they were taken; knows them as being from the same piece of snuff colored cloth as those which witness wears himself, and from the circumstance of the nap in one of the breadths running a different direction from that in the other breadths, the cloth having been cut so through mistake; a button hole had also been improperly cut, which had been sewed up again.

Josiah Cherry, called again.—Assisted in examining the two men when they were in jail, saw some blood on one of the shirt sleeves of one of the men which he accounted for by saying it proceeded from a hurt which he had on his thumb; is not positive there was blood on more than one of the men—thinks there was the appearance of blood on some of the clothes in the trunk found in the house.

George W. Camp, the coroner, sworn.—Examined the prisoner in the jail, and found the letters P. L. marked upon the shirt and [23] waistcoat he had on, which corresponded with the initials of Peter Lagoardette's name on the diploma, and several shirts found in the trunk—discovered blood on the side of the prisoner's shirt immediately under the waistband of his pantaloons, which prisoner accounted for by saying it proceeded from a wound he had over the eye—saw something like the appearance of blood having been washed out of the other prisoner's shirt sleeve; but it might have been a stain of something else.—There were clothes in the room near the body.

C. A. Trincavelli, from Baltimore, sworn.—Had a brother who had left Baltimore last November on business, and when he returned, (from Norfolk) stated that he had sold Demas Castillano, whom he had met with in Norfolk, a pair of pistols (describing them,) and when Castillano, the prisoner at the bar, returned to Baltimore, he showed witness the pair of pistols which he said he had bought from witness' brother while in Norfolk, which pistols, [double-barreled, and of a very singular construction] corresponded precisely with those now presented to the Court [which were found in the trunk near the dead body ]—Pistols of the description sold by witness and his brother, witness had never met with elsewhere in the United States.—Has seen prisoner often wearing pantaloons like those present, [bloody, found in the house of the deceased.]—Prisoner speaks English language tolerably well—has been ten or twelve months in Baltimore, and has understood from himself that he has been ten years in the United States—has also understood from prisoner that he married in Savannah.

Nicholas Beauclerc, sworn—[the principal testimony of this witness has been given before the examining court.]—Was present when Lagoardette applied to Mr. O'Neil to make his pantaloons, but did not hear him give directions about any particular fashion or manner in which he wished them made—Had been acquainted with Lagoardette (this was the name he now called him) for some time.

Mrs. Duesberry, sworn.—Saw two men pass her house on the day of the murder about two o'clock, p. m. [Mrs. D. lives not exceeding one hundred and sixty yards west from, and in full view of, the house where the murder was committed,] one of the men was the prisoner—had never seen them before nor since—they came up Cumberland street, and passed witness' house very quick—saw no baggage or burthen of any kind about them.

[24] W.D.Young, sworn.—About two o'clock, on Tuesday, 20th March, was coming from Armistead's Rope walk, and near Mrs. Duesberry's, met two men, apparently foreigners, one of whom was the prisoner, walking towards Potter's field.

Mr. Jordan, sworn.—Resides about four miles in the country, on Tanner's Creek—The next morning after the murder was committed in Norfolk, a little before sunrise, saw two men, one of whom was the prisoner, come out of a pine thicket near witness' house, where witness supposed from their appearance they had been asleep, one of whom inquired if a ferry was near, and appeared to be very unquiet, fatigued and restless, frequently turning his head first to one direction and then to another—the prisoner inquired the road to the ferry and then again the road and distance to Norfolk, as they said they wished to get to Norfolk—Witness gave them every information they asked for, and they started with the appearance of intending to go to Norfolk; but when they had turned a piece of wood, and supposed out of view of witness (witness is compelled to think so from their conduct,) they took the path which led to Bowdoin's ferry; which witness perceiving, immediately pursued and reached Capt. Shuster's in a short time after they did—[The men, however, had applied to Mrs. Shuster, (Capt. S. being absent,) to have them set over the creek, and witness came up while the boy was in the boat in the act of setting them across.]—Witness informed Mrs. S. of his suspicions, that the two men were the murderers, and advised her to order the boy with the boat back; but the men would not suffer him to return, and one of them evinced great apprehension of danger, by frequent jumping up and sitting down in the boat, while Mrs. S. was giving instructions for its return.

John Wilson, sworn—Capt. Shuster called at witness' house on Wednesday night—(21st March) for him to go in pursuit of the two men who it was supposed had committed the murder in Norfolk the day before—witness started with him, and about sunrise next morning, on what is called Lavender Point, a point projecting out from Sewell's (the main point) saw two men,one of whom was the prisoner, on the beach— witness rode up to them and inquired what they were doing? The answer was, and pointing towards Hampton Roads at the same time "Fransch frigat." Witness informed them, (the other companions of witness coming up at that time,) that they must unbutton their clothes, that he might see whether or not they were armed, which they were not, the party [25] then took them (they expressing a willingness to "give up,") and brought them to Norfolk.

A witness residing in Norfolk, sworn. —Stated, that Friday, sixteenth of March, was a very warm day, for he well recollects that himself and friend, walked round over the bridges from Norfolk to Portsmouth on that day, and that about eight or nine o'clock that night it came on to blow, rain, hail and snow, and the next day (Saturday) the weather was very cold indeed; and that he particularly recollects during the storm on Friday night, he saw a considerable fire on Portsmouth side which he at first thought was a fire in the town, but afterwards ascertained it was bushes at the back of it. [A witness, William Gleeson, who had been examined on oath, turned suddenly round to a gentleman who was sitting near him on hearing the circumstance of the fire in the rear of Portsmouth mentioned, and something which the court overheard and called upon him to explain.] Gleeson stated that the mentioning of the fire in the rear of Portsmouth had reminded him that it was the day after that fire that the two men had called to get the helve for the axe, he had certainly been mistaken before as to the day of the week, and he now well recollected, that it was as he was going to church the next day, Sunday, that he saw the two men crossing the field near the house where the murder was committed, and that it was snowing at the time. [The circumstance as to the weather was ascertained to be a fact.]

W. B. Lawton, sworn.—Recognizes the double barreled pistol, and knows it to be the one found among the other articles in the house of the deceased.

Doct. R. Jeffery, sworn.—On Sunday night previous to the murder, three persons came to his shop to purchase some sarsaparilla—not not recognize the prisoner as one of them—sold them some—saw some sarsaparilla in the house where the body lay, and a decoction of some in a tin bucket, which witness ascertained to be that, by stirring it round with one of the knives, and finding sarsaparilla at the bottom of the bucket. Water in the bucket was also bloody.

John H. Blamire, sworn.—Three men came to Jeffery and Galt's shop on Saturday night previous to the murder to purchase some sarsaparilla—the prisoner was one of the persons, he asked for it in English and handed it to a smaller person, who paid for it—it was probably about half an hour after candle light when they applied.

[26] Josiah Cherry called again.—Stated that on examining the fire place, he found among the cinders a cake, like one which burnt clothes of woolen would be likely to form, it crumbled to pieces on disturbing it—Cannot say whose shirt it was he discovered the blood on.

Ann Barrett called again.—About twelve o'clock on the day of the murder saw a very large smoke coming out of the chimney, it was of a blackish cast, and she could not help taking notice of it—her house was so situated, that she could have seen what was transacting in the room where the dead body was found; had there not have been curtains up at the windows.

The examination of the witnesses closed about five o'clock in the afternoon. Their evidence was then summed up by Gen. Taylor, in a lucid and masterly speech of two hours and an half, in the exordium of which he admonished the jury to he cautious and deliberate in weighing the testimony before them, and not in any respect to suffer their passions to be influenced by any report that might have been put into circulation, which the testimony of the witnesses had not established.—After Gen. Taymor had recapitulated the facts deposed to, he was followed by the prisoner's counsel, Messrs. Allmand and Maxwell, in a strain of chaste and manly eloquence that riveted the attention and commanded the admiration of the numerous auditory, and which was not less honorable to themselves than gratifying to those who heard it.

About twelve o'clock at night the jury retired, and in ten minutes returned with a verdict of "Guilty of Murder in the first degree."

The prisoner heard the verdict of the jury with nearly as much sang froid as he had evinced during the whole of the trial, and appeared very little more moved, by any thing like a thought of what next awaited him, than he probably did while assisting in dissecting Lagoardette.

The jury were all men of respectable standing in society, and not of that cast that are led away by common report unsustained by evidence, or who are overcome by prejudices—but waited, with the most patient anxiety to hear the testimony of the witnesses, the arguments of the counsel, and the instructions of the court—indeed, perhaps no jury ever merited more applause—(and one of the counsel for the prisoner paid them that compliment,) for patience and a desire to do a prisoner and their consciences justice, than did this.

[27] The prisoner was then conducted back to the jail, and after entering the apartment assigned for him, and while preparing to put on his irons, the jailor in searching him, as he had been accustomed to do, found a large pair of scissors secured with a string to the calf of, his leg, and so closely pressed into the flesh, that it appeared miraculous how he could so long have endured the pain which must have been the consequence of the pressure of such an instrument, especially as one of the bows had been broken off to prevent it from projecting beyond the side of the leg and thus disclose the secret of his having instruments about him. —Whether these scissors had been secured there before he was apprehended, or whether an accomplice had placed them there in the night while the prisoner was at the bar, is not known, nor has the prisoner stated.

Friday, the thirteenth April, was the day fixed upon for the trial of the other prisoner, Manuel Philip Garcia—on which day he was brought to the bar about eleven o'clock. The forms with respect to this prisoner were the same as those in the case of Castillano, as they were both included in the same bill of indictment. The same counsel were employed, and, the same evidence given in by the same witnesses.—The jury of course was composed of different persons.— Their names were, W. K. Mackinder, G. Ott, A. Taylor, senr., J. Christie, S. Hodges, J. Croel, R. Fentress, A. Adams, T. Carney, T. Emmerson, J. Granier, and R. Chapman.

The receiving of evidence occupied the Court from twelve until five o'clock in the afternoon; and the pleadings were not concluded until one o'clock the next morning. The jury then retired, and after an absence of precisely six minutes, returned and rendered a verdict of "Guilty of Murder of the first degree."

The prisoner on learning the purport of the verdict exhibited a considerable degree of emotion, not so much, as it appeared the effect of grief and despair, as of chagrin and disappointment, the result of a fallacious confidence he had all along indulged in the inefficacy of our laws to punish capitally upon presumptive evidence.—Not so much from a disposition to doubt the justice of the verdict, as from the failure of the able counsel he had employed to effect his acquittal.

These trials afford a truly gratifying evidence of the admirable structure of our system of jurisprudence, and of the fair and impartial administration of the laws in our Courts of Justice. The unhappy men who have just been tried were taken up and committed to jail under circumstances of almost unheard of atrocity, [28] calculated to inflame the public feeling with horror and disgust, yea with even vengeance itself. Facts are disclosed previous to their trial which stamp their characters and occupations with infamy—in a word they are foreigners, scarcely known in our country but by their crimes; and, in the opinion of every honest mind, meriting a violent and ignominious death.—Yet see these men brought before the tribunal of our Court—there they are recognized as in the robes of innocence—there every indignant feeling, every prejudice, and every sentiment of abhorrence gives place to paternal tenderness and unwavering impartiality. Juries composed of men of character, intelligence and unbiased feelings are summoned to try their cause—counsel of the first standing are employed to defend them—even their prosecutor is the guardian of their rights, and will not permit their cause to be prejudiced by any informality. The evidence is detailed and commented upon—the law is expounded and illustrated—laborious research and critical acumen are indefatigably employed in the investigation; and time and comfort and convenience, are unheeded while a ray of light is left to be elicited, or a doubt remains that the letter of the law and the demands of justice have been strictly and religiously complied with. Upon the termination of such a process of investigation, so conducted, justice, and no more nor less than justice can ensue. It is upon such a process that these unhappy individuals have been found guilty of a crime for which, even by our mild and humane laws, their miserable lives are forfeited.

On Monday, 23d April, the day preceding adjournment of the Court, the two criminals, Castillano and Garcia, convicted of the murder of Peter Lagoardette, were brought to the bar to receive the awful sentence denounced by the laws both of God and man against the most horrid and unnatural crime of which they had been found guilty.

This solemn ceremonial had been postponed from the preceding Saturday, at the request of the counsel for the prisoners, in whose minds there had arisen a question as to the formality of the bill of indictment; but the result of their deliberations was a conviction of its entire legality, and no motion was put in for an arrest of the final judgment.

At one o'clock his Honor, Judge PARKER, proceeded to discharge the high though painful duty imposed on him by the law, of pronouncing the stern decree of Justice, by an address to the prisoners, at once eloquent, pathetic and deeply impressive; the effect [29] of which was strengthened by the appropriate solemnity of his manner of delivery. The awful assurance of their fate, however, produced no visible alteration in the countenances of the criminals. Both declared their innocence, but without any appearance of that deep emotion and restless anxiety which men really innocent, or even the guilty, if not rendered callous to every natural feeling, might have been expected to evince on so trying an occasion. But hardened and crime-blackened wretches like these must be unsusceptible of the influence of human feelings—Inured to the perils of a criminal course of life—conscious of their guilt, while protesting their innocence, and sensible of the justice of that decree which dooms them to the gibbet, the sentence of the Court was regarded by them as a thing of course, as a result to be expected, and therefore possessing none of those appalling attributes which strike terror to hearts less callous, than their own.

The following is the address delivered by the Judge,

Joseph Garcia Castillano and Manuel Philip Garcia,

I am called upon to perform a most painful but necessary duty. A duty which for the first time in my life my official situation compels me to discharge! Although for nearly four years I have presided over this Judicial Circuit, and during that period have unhappily witnessed the arraignment and conviction of many culprits, yet such is the humane tenderness of our law, that the established guilt of no one of them, has touched the life of the offender. The awful punishment of death, has been reserved by that law for a very few crimes, of deep and dangerous malignity, indicating a heart wholly depraved and utterly regardless of social duty—Among which is the crime of wilful, deliberate and premeditated murder. Of the commission of this crime, under circumstances of peculiar atrocity, each of you stand convicted; and you have now been brought to the bar of this Court, to hear pronounced against you the stern but just sentence, which, throughout the whole world, follows such conviction, and which man has awarded in obedience to the commands of his Creator.

No, circumstances can make me cease to regret the necessity I am under of pronouncing your condemnation, but there are several in your case calculated to reconcile your Judges to the fate, which, through their instrumentality, inevitably awaits you.

The principal one is the certainty of your guilt and its crying enormity. Besides the confession of one of you, which was not admitted to go to the jury, the proofs against you were strong, abundant, [30] irresistible. If they were not, technically speaking, positive, they could scarcely be called circumstantial; or, if circumstantial, of that nature which raises a violent presumption, oftentimes equal to full proof. Nor did this presumption arise out of one, but out of many facts established by direct evidence; all of them, singly, affording strong assurance of the justice of the charges against you, and when united perfectly conclusive. They proved beyond a single rational doubt, that actuated by some infernal passion, you committed a shocking and barbarous murder upon the body of Peter Lagoardette, and that afterwards, to prevent detection, with a savage ferocity scarcely less revolting to human nature than the murder itself, you butchered and burnt his yet warm and palpitating limbs. The scene of this bloody and diabolical transaction was a house in the thickly settled part of our town, and the time, day. In such a place, and with the light of heaven shining full upon you, you dared to commit the blackest in the catalogue of human crimes; and instead of flying with instinctive horror from the appalling spectacle, you remained to consummate your wickedness, until fear compelled what conscience could not. Your victim, there is too much reason to believe, was your associate in many acts of villainy and deserved to die; but not by your hands, nor in that cruel, sudden manner.—Although he was a thief and a robber, your crime is not the less; for you are yourselves, as the circumstances of your trial prove, thieves and robbers; and the same disregard of all laws, human and divine, which made you so, prompted to this last act of unparalleled wickedness. But thus it ever is with those who leave the straight forward path of rectitude. They begin with fraud—they pass imperceptibly to theft, rapine and robbery—and they end with murder.

Another circumstance which ought to lessen the regret of all concerned in bringing you to justice, is, that in the investigation of your case the spirit as well as all the forms of the law have been complied with.—Although foreigners, you have had every benefit which could have been extended to the most distinguished of our citizens. You have been tried by unexceptionable juries, and convicted, not without the concurring testimony of all the tribunals, which, in our country, are placed as safeguards over the life of man. And you have been defended with a zeal and ability which did equal honor to the heads and hearts of your counsel. Notwithstanding the prejudices which had been so naturally excited against you in the public mind: notwithstanding the horror which thrilled this whole community when the mutilated trunk and burning limbs of Lagoardette were discovered; notwithstanding each successive [31] day added some new circumstance to the proofs of your connection with that transaction, and thus kept alive public feeling and indignation; yet gentlemen were found who could stifle, if they could not extinguish, those sentiments in their own minds; who interposed themselves fearlessly between you and the torrent which might have overwhelmed you; who invoked and obtained for you a patient and candid hearing; who covered you with the ægis of the law, and urged in your behalf every circumstance and every argument that the facts of your case justified. I rejoice that they did so. I expected no less from a profession distinguished for its humanity, its generosity and its sacred regard to constitutional rights—and I have not been disappointed.

But even your counsel found it impossible to deny the fact of your killing Lagoardette. They contended only, that because the commonwealth could not prove express malice, or a long-settled, predetermined plan to perpetrate the deed, the jury could not infer it from the circumstances, and must therefore find you guilty only of murder in the second degree, under our act of assembly. The legal opinion which this argument drew necessarily from the court on the true construction of that act, I have reviewed carefully and anxiously; and I rest upon it with the utmost confidence. If there had been any thing in it to doubt, your counsel knew how to avail themselves of the error, and the opportunity of carrying your case to the highest criminal tribunal would not have been lost. It was their duty to take care that you should not be condemned “except by the law of the land,” and faithfully have they performed that duty.

Every thing, therefore, in your case conspires to shew that you are fit objects of the punishment denounced against murderers in the first degree. The law and the facts are equally clear, and nothing remains for me, previous to passing your sentence, but to conjure you most earnestly to prepare for DEATH!—Your earthly career must soon terminate. God forbid, that by any expression of opinion I should forestall executive mercy! but duty to state my convictions, that you have nothing further to hope from man in this world. Be not deceived by any vain confidence—Be not flattered by any vain hope. You are separated from eternity by a narrow isthmus, and over that you will soon pass—prepare then for death. Oh, prepare for that awful moment by a timely disclosure of your crimes, by repairing as far as you are able all the wrongs you have done, and by a contrite and unfeigned repentance. At present, according to the feeling remark of your counsel, if you are unfit to live, you are equally unfit to die. [32] But the law is tender and humane to the last. It gives you some time to endeavor to repair the injuries you have done to man and to make your peace with God. It may be, that his mercy will even extend to a late, and unchosen repentance. However improbable, it would be presumption to deny the efficacy of sincere repentance in the latest moments of life, and in so desperate a state, apparent impossibilities are worth attempting. The thief upon the cross was pardoned, and whilst that instance of mercy remains on record, man ought not abandon himself to despair. Once more then, I conjure you to reflect, that you are already cut off from all the hopes, fears and business of this life, that you are dead to the world and its concerns, and that, you, will soon have to answer at the bar of heaven for the crimes committed in the flesh. God grant, that you may in the short interval, between this and your execution, so employ your time, as to obtain forgiveness for those crimes.

The sentence of the Law is,

That you, Joseph Garcia Castillano, and Manuel Philip Garcia, shall be returned to the jail of Norfolk County, whence you came, and that on Friday, the first day of June next, you shall be taken thence by the Coroner of the same County, acting as Sheriff to the common place of execution, where, between the hours of ten o'clock in the forenoon and four o'clock in the afternoon, you and each of you, shall be hanged by the neck until you are dead, and God in his infinite goodness have on your souls.

As soon as the sentence of death was pronounced upon the miserable culprits, they were conducted back to prison, and confined in irons, in separate apartments, as they had been before.