One

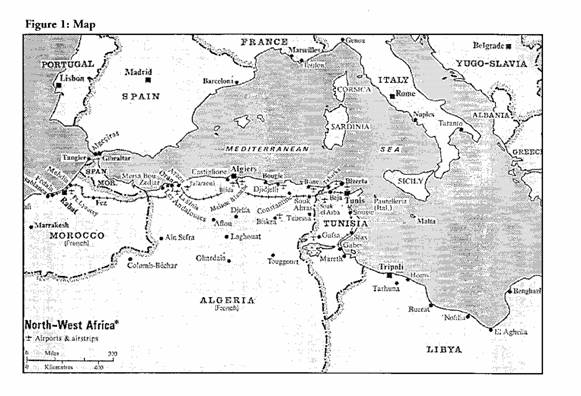

Man's Account of the North African Campaign

During World War II

On January 11, 1942,

only weeks after the bombing of

The

campaign in North Africa began when Mussolini invaded the

When

Goolsby arrived in

World

War II was the B-24D, a heavily-armed bomber plane. *5* It was a custom of the

squadrons to name "their" plane, particularly after women. However, Goolsby's plane was dubbed the "Sad Sac," after a

cartoon character found in a military newspaper, the Stars and Stripes. *6* The B-24

"Liberator," also given a name by the Royal Air Force, was produced

in mass quantities.

The B-24 had a top

speed of 290 mph. Its cruising altitude was 28,000 feet. A major disadvantage

of the B-24's low cruising altitude was that it was difficult to send up

different types of bombers at the same time. The other widely-used bomber plane

at this time, the B17, had a cruising altitude of 30,000 feet. For this

reason, these two planes could never be flown in mixed formation. Had it been

possible, a mixed formation would have allowed an already strong American Airforce to become even more productive.

The B-24 also had a

comprehensive defensive armament. It was produced with ten 50-inch machine guns

located at nose, dorsal, ventral, waist, and tail positions. The operational

range was 2,100 miles, meaning the plane could be flown for that many miles

before having to refuel. In addition to the armament included on the plane, the

Two major

types of bombing strategies used by bomber planes in World War II were

"precision" bombing and "area" bombing. Thanks to the Norden bombsight,

The Norden bombsight was connected to a gyroscope in the

bombardier's plexi-glass compartment located under

the nose in the front of the plane. Parts of the bombsight were removable by

the bombardier. This was designed so that if the plane was ever captured by an

enemy, the highly secretive, American-made bombsight could be removed and

destroyed before being discovered. In fact, bombardiers in World War II,

including Lieutenant Goolsby, were instructed to

destroy the bombsight if ever captured, even if it "meant their

life." *13* Life in the air was hard. It wasn't much better on the ground.

Lieutenant

Goolsby's squadron was stationed in

center of

it. When lit, this provided heat for around thirty minutes. *15* Wartime

conditions seemed to transform ordinary men into ingenious survivors.

For others, stables

would have been a welcome bed, but they had to sleep in pup tents on the ground

where they were very susceptible to various diseases. Contracting malaria was a

major fear, and men had to button their shirts to the top and tuck their pants

into their socks when going out at night. *16* At one time, the epidemic spread to

more than fifty soldiers, including Lieutenant Goolsby.

*17* However, only one casualty was documented. *18*

Food was another major

source of conflict because storage, transport, and preparation was difficult when trying to serve thousands of men. Water

was also scarce in certain areas. In

order to find a decent meal, unrationed water, or a

fitting bed, soldiers usually had to wait for a reprieve. During this time off,

men ventured into neighboring cities that had hotels which provided better

food, more comfortable beds, and a break from the pending stress of war. *19*

Another problem facing soldiers was how to

spend their free time on base. Most men spent it writing home to their

families. Men were given stationary called V-mail, which resembled folded

postcards. They were also given strict instructions about what could and could

not be included in their correspondences. Letters had to be short and contain

nothing more than niceties and small talk. Any letters containing even tiny

inferences about the war were censored. Letters received in the States would

commonly have some parts blacked out, and would be copied onto smaller pieces

of paper. *20* When not writing home, men usually played cards, read whatever

printed materials they could find, or listened to the radio in order to pass

the time and to avoid the lingering question of when they might return home.

Base

living also included adapting to constant raids and terrible field and runway

conditions. In

day. How "glad" the soldiers were when they

returned to their own base where the raids happened only once a day. However,

these once-a-day raids caused enough damage to clutter the fields and destroy

equipment, hindering scheduled take-offs for planes. Muddy runways were not

unusual, either. Tractors would have to come to the aid of bogged down planes

which caused even further delays. *21*

Flight plans were not

the only schedule Goolsby's squadron had to follow.

Daily life was also regimented for the soldiers. For the 480th Antisubmarine group, morning began before daybreak. After

breakfast, men were assigned their duty for the day. *22* The Antisubmarine

squadrons not only patrolled the ocean for any signs of subs, they also, on

occasion, would work on convoy duty. On convoy duty, B-24's would follow army

trucks loaded with equipment, sometimes as far north as

On

July 7, 1943, Goolsby's squadron was on routine Antisubmarine control. After miles and miles of patrolling,

an oil slick was spotted on the water, and the "Sad Sac" began following

it. About eight hours into the flight, with nothing but the Atlantic Ocean

surrounding them, an enemy sub, a German U-Boat, was detected.*24* The B-24's

usually flew over the ocean at an altitude of only 200 feet so that when a

target was spotted it took less time to descend to the bombing altitude of 100

feet.*25* Because the plane was flying so low, the German soldiers on the

submarine spotted the American plane first. From the plane, Goolsby's

squadron could see enemy soldiers scrambling to get inside the submarine. A lone

soldier was given the mission of remaining on top of the

submarine as it began to dive back into the depths of the

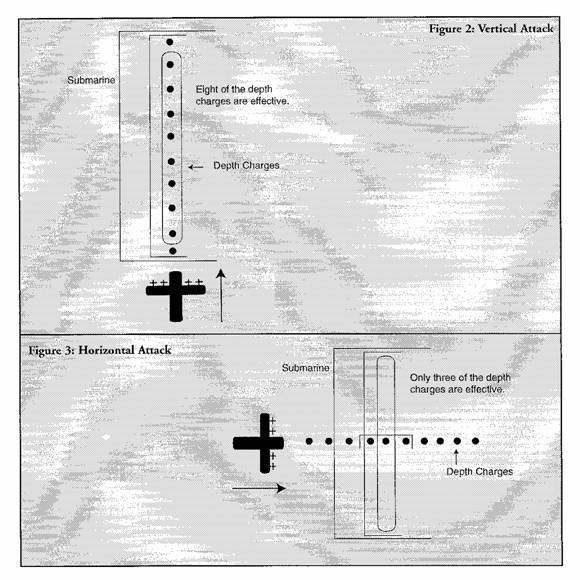

In

order to get optimal bombing results,

the "Sad Sac" would have to approach the U-Boat vertically, from

"stern to stern." *26* This was important

because the ten. depth charges, that were controlled

by a single button in the bombardier's hand, could be dropped the length of the

sub about every 60 yards. (One depth charge had an effective range of about

27

yards.) *27* However, since the

plane was spotted initially by the Germans, the sub had time to maneuver so

that a vertical attack was impossible. The bomber would have to come in horizontally.

This meant that, out of the ten depth charges, only a small fraction would be

effective. The chances that Goolsby

would hit the submarine was severely reduced. *28*

As the "Sad

Sac" began to descend in order to set the bombsight, the German soldier

remaining on top of the U-Boat pointed a 20mm cannon toward the nose of the

plane and fired. *29* It was a direct hit. The plane's flying and firing

mechanisms had not been injured. However,

the co-pilot, navigator, assistant radio operator, and bombardier had. *30* The small compartment surrounding Lieutenant Goolsby had been shattered on one side, and pieces of the

glass and shrapnel had been embedded deeply into his face and body.

After recovering from the hit, the plane

still proceeded to descend to bombing altitude, and the controls were then

handed over to a bloody and wounded bombardier. Horizontally flying over the

diving submarine, the depth charges were released by Goolsby.

One of them crashed into the exact center of the U-Boat. *31* It was blown in

half. The enemy sub and its eighty crew members sunk deep into the

The

attack and victory over the German enemy that day was only half of the battle.

With almost half of the crew injured, the eight hour flight home was to be

unbearable. Goolsby was trapped in the mangled

bombardier's compartment until they reached their base. During those eight

hours, he administered three doses of morphine to himself, two of which had to

be dropped down to him.

Also,

when the German cannon had connected with the nose of the plane, the transmitting

component of the navigating equipment was destroyed. On top of that, the

frequency coming from the base was not being received. Usually, once radio

contact was halted

between the base and planes that were involved in skirmishes,

radio operators at the base had to face the fact that the plane probably wasn't

coming back, especially one that was so far out in the ocean. With the

navigator badly injured, it was up to the pilot to find a good radio frequency

and to use his skills to locate the coordinates of the

Once

removed from the plane, Lieutenant Goolsby was

unrecognizable, even to his own crew. He was taken to the base infirmary and

admitted with serious flesh wounds, but no internal injuries. At the time of

his admittance, there were a number of German war prisoners being cared for.

The infirmary in

Ironically,

after the battle that scarred him for life, Goolsby's

schedule went back to normal. Every morning he ate his breakfast and then

climbed into his compartment under the nose of a B-24. Every day he patrolled

for the same enemy subs, returned to his same home away from home, and then

slept late in the same bed the next day.

On

November 20, 1943, Second Lieutenant James Goolsby

landed at Langley Field,

Among the decorations

and citations awarded to Lieutenant Goolsby were: the

Distinguished Flying

Cross-Air Medal, the Purple Heart, the Distinguished Unit Citation Badge, the EAME Campaign Medal with five Bronze Service Stars, the

American Campaign Medal, and the American Defense Service Medal with one Bronze

Service Star. Following is the citation given along the Distinguished Flying

Cross:

Second Lieutenant James R. Goolsby,

Air

For years, James Goolsby would never talk about the war. He said people that

did, "never really knew what the war was about." For him, knowing

eighty people drown from the push of a button that he held in his hands, could

never be put into words. He always felt responsible, and that somewhere down

the road he would be held accountable for their deaths. *38* The

war did not make Second Lieutenant James Goolsby a

hero. The war made him humble. His love for his country and his

courageous acts made him a hero. The Graceof God

made him my grandfather.

Endnotes