REPORT OF THE COMMISSION TO LOCATE THE SITE OF THE FRONTIER FORTS OF PENNSYLVANIA.

VOLUME TWO.

CLARENCE M. BUSCH.

STATE PRINTER OF PENNSYLVANIA.

1896.

THE FRONTIER FORTS OF WESTERN PENNSYLVANIA.

HANNASTOWN.

Pages 290-332.

By the treaty of November 5th, 1768, with the Six Nations, the right to the occupancy of the lands within the limits of what is called the New Purchase (1.) was given to the Proprietors of the Province. Prior to that time, however, settlements had been made in the southwestern portion of the State, as it is now, under the patronage of Virginia, that colony assuming that the region so settled was within her territorial limits.

At the time of the opening of the land office (April 3d, 1769), for the application of those who desired to take up land in the New Purchase, the same was declared to be within the civil jurisdiction of the county of Cumberland, in which jurisdiction it continued till Bedford county was organized, March 9th, 1771.

The necessity for a new county organization westward of Bedford was so urgent, that Westmoreland county was erected February 26th, 1773. This county was the last one formed under the proprietary government. It embraced all that part of Bedford—and of the Province—lying west of the Laurel Hill, and was circumscribed only by the limits of the line of the New Purchase on the northward, Mason and Dixon's line on the south, and the farthest bounds of the charter grant to the Penns, on the west—limited by the act to where the most westerly branch of the Youghiogheny crossed the boundary line of the Province.

With the organization of the county it was provided that the courts should be held at the house of Robert Hanna until a court-house should be built, and a place definitely fixed by legislation for the county seat. On the 6th of April, 1773, under the reign of "Our Sovereign Lord George the Third, by the Grace of God, of Great Britain, France and Ireland, King, &c.," the first court was organized at Robert Hanna's house before William Crawford, Esq., and his associates, justices of the same court. This was the first place west of the mountains where justice was administered judicially and publicly, under the forms and according to the principles of the English jurisprudence.

No sooner, however, had the legal government of the Penns been established here, than a conflict began between Virginia and the Province touching the rights of the respective colonies in this region—each one claiming this territory. The clashing of authority led to a condition of civil war; the causes of it, its progress, and a recital of its details cannot be given here. These culminated the next year, 1774. At that time John Murray, Lord Dunmore, was the royal governor of Virginia. Himself a subservient tory, his chief tool and representative was one Dr. John Connolly, a Pennsylvanian by birth. The chief representative of the Penns, (2) was Arthur St. Clair, who had held commissions under them for a number of years, and who had been identified with the affairs of the western portion of the Province in various capacities since early in 1770.

Hannastown, the county seat of this larger Westmoreland county, was about thirty-five miles east of Pittsburgh on the Forbes road. Here and eastward to Ligonier, Penns interests were paramount. In many other settlements the inhabitants were largely in sympathy with Virginia.

In the meantime Connolly undertook with a high hand to dominate affairs. He seized upon Fort Pitt, erected a stockade which he called Fort Dunmore, issued proclamations in the name of the Governor of Virginia, commanding all to obey his authority, and proceeded by force against the adherents of Penn at Fort Pitt.

For the issuing of his proclamation and the calling of the militia together in pursuance of it, St. Chair had Connolly arrested on a warrant, brought before him at Ligonier, and committed to jail at Hannastown. Giving bail to answer for his appearance in court, he was released from custody. On being released he went into Augusta county, Va, where at Staunton, the county seat, he was created a justice of the peace. It was alleged that Fort Pitt, was in that county, in the District of West Augusta. This was to give a show of legality to his proceedings, and to cover them with the official sanction of the authority for whom he was acting. When he returned in March it was with both civil and military authority, and his acts from thenceforth were of the most tyrannical and abusive kind.

When the court, early in April, assembled at Hanna's, Connolly, with a force of a hundred and fifty men, armed and with colors, appeared before the place. He placed armed men before the door of the courthouse, and refused admittance to the provincial magistrates without his consent. Connolly had had a sheriff appointed for this region. In the meeting between himself and the justices he said that in coming he had fulfilled his promise to the sheriff, but denied the authority of the court, and that the magistrates had no authority to hold a court. He agreed, however, so far as to let the officers act as a court in matters which might be submitted to them by the people, but only till he should receive instructions to the contrary. The magistrates were outspoken and firm. They averred that their authority rested on the legislative authority of Pennsylvania; that it had been regularly exercised; that they would continue to exercise it, and to do all in their power to preserve public tranquility. They urged the assurance that the proprietary government would use every exertion to have the boundary line satisfactorily adjusted, and that at least by fixing upon a temporary boundary the differences could be accommodated till one should be ascertained.

At this time, 1774, broke out the war in which the Indians made special head against the Virginians on the border of what we now call southwestern Pennsylvania and northwestern West Virginia. The effect of this uprising, added to the condition of the people under the tyrannizing of Connolly, created a panic which led almost to the depopulation of our frontiers. During this time Arthur St. Clair, Aeneas Mackay, Devereux Smith and other staunch friends of the Penns, by their personal influence alone succeeded in quieting the Indians on the northern frontier and west of the Allegheny, and in allaying the fears of the people.

St. Clair writing to Gov. Penn from Ligonier, May 29th, 1774, says: "The panic that has struck this Country, threatening an entire Depopulation thereof, induced me a few days ago to make an Excusion to Pittsburgh to see if it could be removed and the Desertion prevented."The only probable Remedy that offered was to afford the People the appearance of some Protection, accordingly Mr. Smith, Mr. Mackay, Mr. Butler, and some other of the Inhabitants of Pittsburgh, with Collonel Croghan and myself, entered into an Association for the immediate raising an hundred Men, to be employed as a ranging Company to cover the Inhabitants in case of Danger, to which Association several Magistrates and other Inhabitants have acceded, and in a very few days they will be on foot.

"We have undertaken to maintain for one Month at the rate of one Shilling six-pence a Man per Diem; this we will chearfully discharge; at the same time. We flatter ourselves that your Honour will approve the Measure, and that the Government will not only relieve private Persons from the Burthen, but take effectual Measures for the safety of this Frontier, and this I am desired by the People in general to request of your Honor." (3.)

Col. John Montgomery writes to Gov. Penn from Carlisle, June 3, 1774:

"I am just Returned from the Back Country. I was up at the place where Courts are held in Westmoreland County; I found the people there in great Confusion and Distress, many families returning to this side the mountains, others are about Building of forts in order to make a Stand; But They are in Great want of Ammunition and Arms, and Cannot get Sufficient Supply in those parts. I wish some method wou'd be Taken to Send a Supply from Philadelphia, and unless they are Speedily furnished with arms & ammunition will be obliged to Desert the Country. There is a fine Appearance of Crops over the mountains, and Could the people be protected in Saving them, it would be of Considerable Advantage in Case we should be involved in an Indian Warr and Obliged to raise Troops, to be able to Support them with provisions in that Country. Capt'n Sinclair has wrote to your Honour a full State of Affairs in the Back Country, whose letter I send by Express from this place." (4.)

The next year 1775, was one full of excitement; and although civil affairs were unsettled in the early part of the year there was a lull toward spring time of a short duration. Public affairs of much greater moment were attracting the attention of the people. The New England colonies were in open revolt against the mother country. For a time, civil and local disputes and antipathies were allowed to rest, and common danger and a common patriotism led to a unity of the factions.

On the 16th of May, 1775, the inhabitants of Westmoreland county met at Hannastown in convention and then and there produced those remarkable Resolutions which, as long as our annals are preserved will keep the memory of this place ever fresh in the notice of men.

The Minute and Resolutions are as follows:

"Meeting of the inhabitants of Westmoreland county, Pa.

"At a general meeting of the inhabitants of the County of Westmoreland, held at Hanna's town the 16th day of May, 1775, for taking into consideration the very alarming situation of the country, occasioned by the dispute with Great Britain:

"Resolved unanimously, That the Parliament of Great Britain, by several late acts, have declared the inhabitants of the Massachusetts Bay to be in rebellion, and the ministry, by endeavoring to enforce those acts, have attempted to reduce said inhabitants to a mere wretched state of slavery than ever before existed before in any state or country. Not content with violating their constitutional and chartered privileges, they would strip them of the rights of humanity, exposing their lives to the wanton and unpunishable sport of licentious soldiery, and depriving them of the very means of subsistence.

"Resolved unanimously, That there is no reason to doubt but the same system of tyranny and oppression will (should it meet success in Massachusetts Bay) be extended to other parts of America: It is therefore become the indispensable duty of every American, of every man who has any public virtue or love for his country, or any bowels for posterity, by every means which God has put in his power, to resist and oppose the execution of it; that for us we will be ready to oppose it with our lives and fortunes. And the better to enable us to accomplish it, we will immediately form ourselves into a military body, to consist of companies to be made up out of the several townships under the following association, which is declared to be the association of Westmoreland County.

"Possessed with the most unshaken loyalty and fidelity to His Majesty, King George the Third, whom we acknowledge to be our lawful and rightful King, and who we wish may be the beloved sovereign of a free and happy people throughout the whole British Empire, we declare to the world, that we do not mean by this Association to deviate from that loyalty which we hold it our bounden duty to observe; but, animated with the love of liberty, it is no less our duty to maintain and defend our rights (which, with sorrow, we have seen of late wantonly violated in many instances by a wicked Ministry and a corrupted Parliament) and transmit them to our posterity, for which we do agree and associate together:

"1st. To arm and form ourselves into a regiment or regiments, and choose officers to command us in such proportions as shall be thought necessary.

"2d. We will, with alacrity, endeavor to make ourselves masters of the manual exercise, and such evolutions as may be necessary to enable us to act in a body in concert, and to that end we will meet at such times and places as shall be appointed either for the companies or the regiment, by the officers commanding each when chosen.

"3d. That should our country be invaded by a foreign enemy, or should troops be sent from Great Britain to enforce the late arbitrary acts of its Parliament, we will cheerfully submit to military discipline, and to the utmost of our power resist and oppose them, or either of them, and will coincide with any plan that may be formed for the defence of America in general, or Pennsylvania in particular.

"4th. That we do not wish or desire an innovation, but only that things may be restored to and go on in the same way as before the era of the Stamp Act when Boston grew great, and America was happy. As a proof of this disposition, we will quietly submit to the laws by which we have been accustomed to be governed before that period, and will, in our several or associate capacities, be ready when called on to assist the civil magistrate to carry the same in execution.

"5th. That when the British Parliament shall have repealed their late obnoxious statutes, and shall recede from their claim to tax us, and make laws for us in every instance; or some general plan of union or reconciliation has been formed and accepted by America, this our Association shall be dissolved; but till then it shall remain in full force; and to the observation of it, we bind ourselves by everything dear and sacred amongst men.

"No licensed murder! no famine introduced by law!

"Resolved, That on Wednesday, the twenty-fourth instant, the townships meet to accede to the said Association, and choose their officers."

Arthur St. Clair in a letter to Joseph Shippen, Jr., from Ligonier, May 18th, 1775, says: "Yesterday, we had a county meeting and have come to resolutions to arm and discipline, and have formed an Association, which I suppose you will soon see in the papers. God grant an end may be speedily put to any necessity to such proceedings. I doubt their utility, and am almost as much afraid of success in this contest as of being vanquished." (5.)

To Gov. Penn, May 25th, he says: "We have nothing but musters and committees all over the country, and everything seems to be running into the wildest confusion. If some conciliating plan is not adopted by the Congress, America has seen her golden days, they may return, but will be preceded by scenes of horror. An association is formed in this county for defense of American Liberty. I got a clause added, by which they bind themselves to assist the civil magistrates in the execution of the laws they have been accustomed to be governed by."

This clause was the fourth one. This was the first step taken by St. Clair as a Revolutionary patriot. It shows a conservative spirit, and an unwillingness to do anything that might tend to anarchy or violation of just laws. (6.)

When with these people the actual war of the Revolution began, the situation of affairs in the western part of the Province was peculiar. The British government early employed the savages as their allies in the war with the colonies; and although a regiment of men—(seven companies of which were made up of Westmorelanders)—joined the Continental Army under Washington, yet the brunt of the war here had, for the time being to be borne by these people unaided and alone. Early in the war, a department was created called the Western Department, of which Fort Pitt was the headquarters, which was under command of a continental officer and a force mostly of regular soldiers, to which in times of emergency were added the militia of the counties.

The structure called a fort erected in 1774 at Hannastown was doubtless of a very temporary character, intended only, as it was, for the emergency. From early in 1776 there were quarters here for the accommodation of the regulars of the Eighth Penn'a Regiment and of the militia companies which from time to time were recruited. In 1776 it was a point where supplies were collected, and it so continued to be until the destruction of the place which was one of the last acts in the War. While it continued to be a recruiting and distributing station, there was also a fort erected here in 1776 which with the necessary additions was kept up until the day in which it did good stead for those who sought its shelter, as we shall see later.

From the Minutes of the Supreme Executive Council for Dec. 17th, 1790, among the reports of the Treasurer, Comptroller and Register-General, the following account, among others, was read and approved, vizt: "Of David Semple, for superintending the building of the fort at Hanna's Town in the year 1776, by order of Messieurs [Edward] Cook, [James] Pollock and [Archibald] Lockry, amounting to twenty-two pounds. (7.)

In a letter of Col. Lochry to the President of the Council of date Nov. 4th, 1777, referred to elsewhere, in which he sums up the tale of Indian depredations, he says—"We have likewise ventured to erect two stockade forts, at Ligonier and Hannas Town at the Public Expense, with a Store House in each to secure both Public and private property in and be a place of retreat for the suffering frontiers in case of necessity, which I flatter myself will meet your excellency's approbation."

It is altogether probable that the fort here alluded to was but an improvement or an addition to the fort then standing. This, however, is only supposition; and if it was a new structure altogether it took the place of the earlier one.

There are many reports of the Indians being in the neighborhood and of the people fleeing to Hannastown from this time on. The place, however, escaped an attack from the fact, probably, of there being constantly kept there either soldiers of the regular service or squads of militia, with a supply of arms and ammunition. The quantity of supplies was often extremely meagre.

Col. Lochry to President Reed from Hannastown, May 1st, 1779, says.—"The savages are continually making depredations among us; not less than forty people have been killed, wounded or captivated this spring, and the enemy have killed our creatures within three hundred yards of this town." (8.)

Col. Lochry writes to Col. Brodhead from Hannastown, 13th of Dec., 1779, at a time when the people were suffering much and apprehending an outbreak in the spring, in which letter he says: "His Excellency, the president of this state, has invested me with authority to station Capt. Erwin and Capt. Campbell's companies of rangers to cover this county, where I may think their service will be of the most benefit to the distressed frontiers. I have received orders for that purpose. In consequence of which orders, I request you (sir) to send these troops to this place as soon as possible, where I shall assign them stations that I flatter myself their service will be of more benefit to this county than it can possibly be in Fort Pitt." (9.)

Col. Lochry from his home on the Twelve Mile Run writes to Pres. Reed, June 1st, 1780: "1 have been under the necessity of removing the public records of the county from Hannastown to my own plantation on the Twelve Mile Run—not without consulting the judge of the Court who was of opinion it would be no prejudice to the inhabitants. My principal reason for moving them, I did not think them safe as the place is but weak, and is now a real frontier." (10.)

The fall of 1781 was a gloomy one indeed to the people of Westmoreland county. This was the period of the ill-fated Lochry expedition. Besides all this they were harassed all the summer from the inroads of the savages. Col. Lochry to President Reed, (11) July 4th, 1781, says: "We have very distressing times here this summer. The enemy are almost constantly in our country, killing and captivating the inhabitants."

In August, 1781, the detachment of the Seventh Maryland regiment, which had been serving under Brodhead, left Fort Pitt, and returned over the mountains home.

In a letter to Washington of Dec. 3d, 1781, (12) Irvine said:

"At present the people talk of flying early in the spring, to the eastern side of the mountain, and are daily flocking to me to inquire what support they may expect."

It was very generally believed, and Washington himself shared in the opinion, that the failure of Clark (with Lochry) and Gibson, in their expeditions of that year, would greatly encourage the savages to fall on the frontiers with double fury in the coming spring.

The month of Feb., 1782, was one of unusual mildness. War parties of savages from Sandusky visited the settlements and committed depredations earlier than usual on that account. From the failure of the expeditions of the previous autumn, before alluded to, there had been a continued fear all along the border during the winter; and now that the early melting of the snow had brought the savages to the settlements at an unwonted season, a more than usual degree of excitement and apprehension prevailed. (13.).

Through the spring and summer of 1782 the settlers gathered together at various points of convenience, living in common and preserving the strictest watch. While the gloom from repeated disasters still rested upon the people, they gathered into the cabins about Hannastown and nearer the blockhouses and stations. The militia in the service of the State had deserted from the posts, because they were not paid and were in rags. The whole country north of the Great Road almost to the rivers northwestward was, so to speak, deserted.

Such was the condition of affairs at the time when Hannastown was attacked, on Saturday, July 13th, 1782, and almost totally destroyed, an event of the greatest historical importance in the annals of Western Pennsylvania. The first of the following articles is from the pen of the Hon. Richard Coulter, at that time a practicing attorney of the Westmoreland bar, and later one of the Justices of the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania. It was printed in the Pennsylvania Argus, published at Greensburg, Pa., in 1836. Judge Coulter obtained his information from the persons who had been a part of what he narrates:

"About three miles from Greensburg, on the old road to New Alexandria, there stand two modern built log tenements, to one of which a sign-post, and a sign is appended, giving due notice that at the seven yellow stars, the wayfarer may partake of the good things of this world. Between the tavern and the Indian gallows hill on the west, once stood Hanna's town, the first place west of the Allegheny mountains where justice was dispensed according to the legal forms of the white man. The county of Westmoreland was established by the provincial legislature on the 26th of Feb., 1773, and the courts directed to be held at Hanna's town. It consisted of about thirty habitations, some of them cabins, but most of them aspiring to the name of houses, having two stories, of hewed logs. There were a wooden court house and a jail of the like construction. A fort stockaded with logs, completed the civil and military arrangements of the town. The first prothonotary and clerk of he courts was Arthur St. Clair, Esq., afterwards general in he revolutionary army. Robert Hanna, Esq., was the first residing justice in the courts; and the first Court of Common Pleas was held in April, 1773. Thomas Smith, Esq. afterwards one of the judges on the supreme bench, brought quarterly, from the east, the most abstruse learning of the profession, to puzzle the backwoods lawyers; and it was here that Hugh Henry Brackenridge, afterwards also a judge on the supreme bench, made his debut, in the profession which he afterwards illustrated and adorned by his genius and learning. The road first opened to Fort Pitt by Gen. Forbes and his army, passed through the town. The periodical return of the court brought together a hardy, adventurous, frank, and open-hearted set of men from the Redstone, the George's creek, the Youghiogheny, the Monongahela, and the Catfish settlements, as well as from the region, now in its circumscribed limits, still called "Old Westmoreland." It may well be supposed that on such occasions, there was many an uproarious merrymaking. Such men, when they occasionally met at courts, met joyously. But the plough has long since gone over the place of merry-making; and no log or mound of earth remains to tell where justice held her scales.

"On the 13th July, 1782, a party of the townsfolk went to O'Connor's fields, about a mile and a half north of the village, to cut the harvest of Michael Huffnagle. * * * * * The summer of ‘82 was a sorrowful one to the frontier inhabitants. The blood of many a family had sprinkled their own fields. The frontier northwest of the town was almost deserted; the inhabitants had fled for safety and repose towards the Sewickley settlement. At this very time there were a number of families at Miller's station, about two miles south of the town. There was, therefore, little impediment to the Indians, either by way of resistance, or even of giving warning of their approach. When the reapers had cut down one field, one of the number who had crossed to the side next to the woods, returned in great alarm, and reported that he had seen a number of Indians approaching. The whole reaping party ran for the town, each one intent upon his own safety. The scene which then presented itself may more readily be conceived than described. Fathers seeking for their wives and children, and children calling for their parents and friends, and all hurrying in a state of consternation to the fort. Some criminals were confined in jail, the doors of which were thrown open. After some time it was proposed that some person should reconnoitre, and relieve them from uncertainty. Four young men, David Shaw, James Brison, and two others, with their rifles, started on foot through the highlands, between that and Crabtree creek, pursuing a direct course towards O'Connor's fields, whilst Captain Matthew Jack, who happened to be in the town, pursued a more circuitous route on horse back.

"The captain was the first to arrive at the fields, and his eye was not long in doubt, for the whole force of the savages was there mustered. He turned his horse to fly, but was observed and pursued. When he had proceeded a short distance, he met the four on foot—told them to fly for their lives—that the savages were coming in great force—that he would take a circuitous route and alarm the settlements. He went to Love's, where Frederick Beaver now lives, about a mile and a quarter east of the town, and assisted the family to fly, taking Mrs. Love on the horse behind him. The four made all speed for the town, but the foremost Indians obtained sight of them, and gave them hot pursuit. By the time they had reached the Crabtree creek, they could hear the distinct footfalls of their pursuers, and see the sunbeams glistening through the foliage of the trees upon their naked skins. When, however, they got into the mouth of the ravine that led up from the creek to the town, they felt almost secure. The Indians, who knew nothing of the previous alarm given to the town, and supposed they would take it by surprise, did not fire, lest they might give notice of their approach; this saved the lives of David Shaw and his companions. When they got to the top of the hill, the strong instinct of nature impelled Shaw to go first into the town, and see whether his kindred had gone to the fort, before he entered it himself. As he reached his father's threshold and saw all within desolate, he turned and saw the savages, with their tufts of hair flying in the wind, and their brandished tomahawks, for they had emerged into the open space around he town, and commenced the war-hoop. He resolved to make me of them give his death halloo, and raising his rifle to his eye, his bullet whizzed true, for the stout savage at whom he aimed bounded into the air and fell upon his face. Then, with the speed of an arrow, he fled to the fort, where he entered in safety. The Indians were exasperated when they found the town deserted, and after pillaging the houses, they set them on fire. Although a considerable part of the town was within rifle range of the fort, the whites did but little execution, being more intent on their own safety than solicitous about destroying the enemy. One savage, who had put on the military coat of one of the inhabitants, paraded himself so ostentatiously that he was shot down. Except this one, and the one laid low by Shaw, there was no evidence of any other execution, but some human bones found among the ashes of one of the houses, where they, it was supposed, burnt those who were killed. There was not more than fourteen or fifteen rifles in the fort; and a company having marched from the town some time before, in Lochry's ill-fated campaign, many of the most efficient men were absent; not more than 20 or 25 remained. A maiden, Jannet Shaw, was killed in the fort; a child having run opposite the gate, in which there were some apertures through which a bullet from the Indians occasionally whistled, she followed it, and as she stooped to pick it up, a bullet entered her bosom—thus she fell a victim to her kindness of heart. The savages, with their wild yells and hideous gesticulations, exulted as the flames spread, and looked like demoniacs rejoicing over the lost hopes of mortals.

"Soon after the arrival of the marauders, a large party of them was observed to break off, by what seemed concerted signals, and march towards Miller's station. At that place there had been a wedding the day before. Love is a delicate plant, but will take root in the midst of perils in gentle bosoms. A young couple, fugitives from the frontier, fell in love and were married. Among those who visited the bridal festivity, were Mrs. Hanna, and her two beautiful daughters, from the town. John Brownlee, who then owned what is now the fine farm of Frederick J. Cope, and his family, were also there. This individual was well known in frontier forage and scouting parties. His courage, activity, generosity, and manly form, won for him among his associates, as they win everywhere, confidence and attachment. Many of the Indians were acquainted with his character, some of them probably had seen his person. There were in addition to the mansion a number of cabins, rudely constructed, in which those families who had been driven from their homes resided. The station was generally called Miller's town. The bridal party were enjoying themselves in the principal mansion, without the least shadow of approaching danger. Some men were mowing in the meadow—people in the cabins were variously occupied—when suddenly the war-whoop, like a clap of thunder from a cloudless sky, broke upon their astonished ears. The people in the cabins and those in the meadow, mostly made their escape. One incident always excites emotions in my bosom when I have heard it related. Many who fled took an east course, over the long steep hills which ascend towards Peter George's farm. One man was carrying his child, and assisting his mother in the flight, and when they got towards the top of the hill, the mother exclaimed they would be murdered, that the savages were gaining space upon them. The son and father put down and abandoned his child that he might more effectually assist his mother. Let those disposed to condemn, keep silence until the same struggle of nature takes place in their own bosoms. Perhaps he thought the savages would be more apt to spare the innocence of infancy than the weakness of age. But most likely it was the instinct of feeling, and even a brave man had hardly time to think under such circumstances. At all events, Providence seemed to smile on the act, for at the dawn of the next morning, when the father returned to the cabin, he found his little innocent curled upon his bed, sound asleep, the only human being left amidst the desolation. Let fathers appreciate his feelings; whether the Indians had found the child and took compassion on it, and carried it back, or whether the little creature had been unobserved, and when it became tired of its solitude, had wandered home through brush and over briers, will never be known. The latter supposition would seem most, probable from being found in its own cabin and on its own bed. At the principal mansion, the party were so agitated by the cries of women and children, mingling with the yell of the savage, and all were for a moment irresolute, and that moment sealed their fate. One young man of powerful frame grasped a child near him, which happened to be Brownlee's, and effected his escape. He was pursued by three or four savages. But his strength enabled him to gain slightly upon his followers, when he came to a rye field, and taking advantage of a thick copse, which lay by a sudden turn intervened between him and them, he got on the fence and leaped far into the rye, where he lay down with the child. He heard the quick tread of the savages as they passed and their slower steps as they returned, muttering their guttural disappointment. That man lived to an honored old age, but is now no more. Brownlee made his way to the door, having seized a rifle; he saw, however, that it was a desperate game, but made a rush at some Indians who were entering the gate. The shrill clear voice of his wife, exclaiming, "Jack, will you leave me?" instantly recalled him, and he sat down beside her at the door, yielding himself a willing victim. The party were made prisoners, including the bridegroom and bride, and several of the family of Miller. At this point of time, Capt. Jack, was seen coming up the lane in full gallop. The Indians were certain of their prey, and the prisoners were dismayed at his rashness. Fortunately he noticed the peril in which he was placed in time to save himself. Eagerly bent upon giving warning to the people, his mind was so engrossed with that idea, that he did not see the enemy until he was within full gun-shot. When he did see them, and turned to fly, several bullets whistled by him, one of which cut his bridle-rein, but he escaped. When those of the marauders who had pursued the fugitives returned, and when they had safely secured their prisoners and loaded them with plunder, they commenced their retreat.

"Heavy were the hearts of the women and maidens as they were led into captivity. Who can tell the bitterness of their sorrow? They looked, as they thought, for the last time upon the dear fields of their country, and of civilized life They thought of their fathers, their husbands, their brothers, and, as their eyes streamed with tears, the cruelty and uncertainty which hung over their fate as prisoners of savages overwhelmed them in despair. They had proceeded about half a mile, and four or five Indians near the group of prisoners in which was Brownlee were observed to exchange rapid sentences among each other, and look earnestly at him. Some of the prisoners had named him, and, whether it was from that circumstance or because some of the Indians had recognized his person, it was evident that he was a doomed man. He stooped slightly to adjust his child on his back, which he in addition to the luggage which they had put on him; as he did so, one of the Indians who had looked so earnestly at him stepped to him hastily and buried a tomahawk in his head. When he fell, the child was quickly dispatched by the same individual. One of the women captives screamed at this butchery, and the same bloody instrument and ferocious hand immediately ended her agony of spirit. God tempers the wind to the shorn lamb, and He enabled Mrs. Brownlee to bear that scene in speechless agony of woe. Their bodies were found the next day by the settlers and were interred where they fell. The spot is marked to this day in Mechling's field. As the shades of evening began to fall, the marauders met again on the plains of Hanna's town. They retired into the low grounds about the Crabtree creek, and there regaled themselves on what they had stolen. It was their intention to attack the fort the next morning before the dawn of day.

"At nightfall thirty yeomen, good and true, had assembled at George's farm, not far from Miller's, determined to give, that night, what succor they could to the people in the fort. They set off for the town, each with his trusty rifle, some on horseback and some on foot. As soon as they came near the fort the greatest caution and circumspection was observed. Experienced woodsmen soon ascertained that the enemy was in the Crab-tree bottom, and that they might enter the fort. Accordingly, they all marched to the gate, and were most joyfully welcomed by those within. After some consultation, it was the general opinion that the Indians intended to make an attack the next morning and, as there were but about forty-five rifles in the fort, and about fifty-five or sixty men, the contest was considered extremely doubtful, considering the great superiority of numbers on the part of the savages. It became, therefore, a matter of the first importance to impress the enemy with a belief that large reinforcements were arriving. For that purpose the horses were mounted by active men and brought full trot over the bridge of plank that was across the ditch which surrounded the stockading. This was frequently repeated. Two old drums were found in the fort, which were new braced, and music on the fife and drum was kept occasionally going during the night. While marching and counter marching, the bridge was frequently crossed on foot by the whole garrison. These measures had the desired effect. The military music from the fort, the trampling of the horses, and the marching over the bridge, were borne on the silence of night over the low lands of the Crab-tree, and the sounds carried terror into the bosoms of the cowardly savages. They feared the retribution which they deserved, and fled shortly after midnight in their stealthy and wolf-like habits. Three hundred Indians, and about sixty white savages in the shape of refugees, (as they were then called,) crossed the Crab-tree that day, with the intention of destroying Hanna's town and Miller's station.

"The next day a number of the whites pursued the trail as far as the Kiskiminetas without being able to overtake them.

"The little community, which had now no homes but what the fort supplied, looked out on the ruins of the town with the deepest sorrow. It had been the scene of heartfelt joys—embracing the intensity and tenderness of all which renders the domestic hearth and family altar sacred. By degrees they all sought themselves places where they might, like Noah's dove, find rest for the soles of their feet. The lots of the town, either by sale or abandonment, became merged in the adjoining farm; and the labors of the husbandman soon effaced what time might have spared. Many a tall harvest have I seen growing upon the ground; but never did I look upon its waving luxuriance without thinking of the severe trials, the patient fortitude, the high courage which characterized the early settlers.

"The prisoners were surrendered by the Indians to the British in Canada. The beauty and misfortune of the Misses Hanna attracted attention; and an English officer—perhaps moved by beauty in distress to love her for the dangers she had passed—wooed and won the fair and gentle Marian. After the peace of ‘83 the rest of the captives were delivered up, and returned to their country."

The papers which follow contain information relative to the destruction of the place. The first account is the following:

Michael Huffnagle to Irvine:

"Hannastown, July 14, 1782.

‘Dear Sir :—At the request of Major Wilson, I am sorry to inform you that yesterday about two o'clock, this town was attacked by about one hundred Indians, and in a very little time the whole town except two houses were laid in ashes. The people retired to the fort where they withstood the attack, which was very severe until after dark when they left us. The inhabitants here are in a very distressed situation, having lost all their property but what clothing they had on."At the same time we were attacked here, another party attacked the settlement. What mischief they may have done we have not been able as yet to know; only that Mr. Hanna, here, had his wife and his daughter Jenny taken prisoners. Two were wounded—one out of the fort and one in. Lieutenant Brownlee and one of his children with one White's wife and two children were killed about two miles from this town.

"This far I wrote you this morning. The express has just returned and informs that when he came near Brush Run the Indians had attacked that place, and he was obliged to return. If you consider our situation, with only twenty of the inhabitants, seventeen guns and very little ammunition, to stand the attack in the manner we did, you will say that the people behaved bravely. I have lost what little property I had here, together with my papers. The records of the county, I shall, as soon as I can get horses, remove to Pittsburgh, as this place will in a few days be vacated. You will please to mention to Mr. Duncan to do all he can for the supplying of the garrison until I shall be able to get a horse, having lost my horse, saddle and bridle."

Michael Huffnagle to Irvine:

"Hannastown, July 17, 1782,—4 o clock P. M.

"Dear General: —I just this moment received yours by the soldier. I should have sent you an express on Saturday night, but could get no person to go, as the enemy did not entirely leave us until Sunday morning. A party of about sixty of our people went out last Monday and found where they were encamped within a mile of this place. And from the appearance of the camp they must have staid there all day Sunday. We have had parties out since and find their route to be towards the Kiskiminetas and that they have a large number of horses with them. They have likewise killed about one hundred head of cattle and horses and have only left about half a dozen horses for the inhabitants here."Last Sunday morning, the enemy attacked at one Freeman's upon Loyalhanna, killed his son and took two daughters prisoners. From the best account I can collect, they have killed and taken twenty of the inhabitants hereabouts and burn and destroy as they go along. I take the liberty of mentioning if a strong party could follow that they might still be come up with them; having so much plunder and so many horses with them, I Imagine they will go slow. As for the country rousing and following them, I am afraid we need not put any dependence on it; as several parties, some of thirty, others of fifty [men], would come in on Sunday and Monday last and stay about one hour, pity our situation and push home again.

"I am much afraid that the scouting parties stationed at the different posts have not done their duty. We discovered where the enemy had encamped and they must have been there for at least about ten days; as they had killed several horses and eat them about six miles from Brush Run and right on the way towards Barr's fort. This morning about four miles from this place towards the Loyalhanna one of the men from this fort discovered four Indians whom he took to be spies.

"I have mentioned to the inhabitants the subject of making a stand here. They are willing to do everything in their power if assistance could be given them. It will take at least fifty men to keep a guard in the garrison and guard the people to get in their little crops, which ought to be done immediately; otherwise, they will be entirely lost. By a small party that returned last evening, I am informed from the different camps they saw, there must at least have been about two hundred of the enemy, and from the different accounts we have from all quarters, it seems that they had determined to make a general attack upon the frontiers.

"Sheriff [Matthew] Jack has been kind enough to let me have a horse; tomorrow morning, I shall set out, and in a few days shall supply you with some whisky and cattle. I have just this moment been informed that Richard Wallace and one Anderson who were with Lochry, made their escape from Montreal and have arrived safe in this neighborhood. As soon as I shall be able to procure what intelligence they have, I shall inform you.

"P. S.—The inhabitants of this place having lost what provisions they had, they made application to me to supply them with some. I had a quantity of flour and some meat. I took the liberty of supplying them and hope it will meet with your approbation; and when I shall see you [you can give] me particular directions for that purpose." (13.)

Michael Huffnagle to President Moore:

"Fort Reed, July 17, 1782.

"Sir :—I am sorry to inform your excellency, that last Saturday, at two o clock in the afternoon, Hannastown was attacked by about one hundred whites and blacks [Indians]. We found several jackets, the buttons marked with the king's eighth regiment. At the same time this town was attacked, another party attacked Fort Miller, about four miles from this place. Hannastown and Fort Miller, in a short time, were reduced to ashes, about twenty of the inhabitants killed and taken, about one hundred head of cattle, a number of horses and hogs killed. Such wanton destruction I never beheld,—burning and destroying as they went. The people of this place behaved bravely; retired to the fort, left their all a prey to the enemy, and with twenty men only, and nine guns in good order, we stood the attack until dark. At first, some of the enemy came close to the pickets, but were soon obliged to retire farther off. I cannot inform you what number of the enemy may be killed, as we saw them from the fort carrying off several."The situation of the inhabitants is deplorable, a number of them not having a blanket to lie on, nor a second suit to put on their backs. Affairs are strangely managed here; where the fault lies I will not presume to say. This place being of the greatest consequence to the frontiers,—to be left destitute of men, arms, and ammunition, is surprising to me, although frequent applications have been made. Your excellency, I hope, will not be offended my mentioning that I think it would not be amiss that proper inquiry should be made about the management of the public affairs in this county; and also to recommend to the legislative body to have some provision made for the poor distressed people here. Your known humanity convinces me that you will do everything in your power to assist us in our distressed situation." (14)

The following is an extract from a letter written by Ephraim Douglass at Pittsburgh, July 26, 1782 (15):

"My last contained some account of the destruction of Hannastown, but it was an imperfect one—the damage was greater than we knew, and attended with circumstances different from my representation of them. There were nine killed and twelve carried off prisoners, and, instead of some of the houses without the fort being defended by our people, they all retired within the miserable stockade, and the enemy possessed themselves of the forsaken houses, from whence they kept a continual fire upon the fort from about twelve o'clock till night, without doing any other damage than wounding one little girl within the walls. They carried away a great number of horses and everything of value in the deserted houses, destroyed all the cattle, hogs, and poultry within their reach, and burned all the houses in the village except two, these they also set fire to, but, fortunately it did not extend itself so far as to consume them; several houses round the country were destroyed in the same manner, and a number of unhappy families either murdered or carried off captives—some have since suffered a similar fate in different parts—hardly a day but they have been discovered in some quarter of the country, and the poor inhabitants struck with terror thro' the whole extent of our frontier. Where this party set out from is not certainly known, several circumstances induce the belief of their coming from the heads of the Allegheny or toward Niagara, rather than from Sandusky or the neighborhood of Lake Erie. The great number of whites known by their language to have been in the party, the direction of their retreat when they left the country, which was toward the Kittanning, and no appearance of their tracks either coming or going, have been discovered by the officer and party which the general ordered on that service beyond the river, all conspire to support this belief."

David Duncan to Mr. [James] Cunningham, member of the Council from Lancaster, writes: (16.)

"Pittsburgh, July 30, 1782.

‘Dear Sir:—I have taken the liberty of writing you the situation of our unhappy country at present. In the first place, I make no doubt but you have heard of the bad success of our campaign against the Indian towns [Crawford's campaign against Sandusky], and the late stroke the savages have given Hannastown, which was all reduced to ashes except two houses, exclusive of a small fort, which happily saved all who were so fortunate as to get to it. There were upwards of twenty killed and taken, the most of whom were women and children. At the same time, a small fort [Miller] four miles from thence, was taken, supposed to be by a detachment of the same party. I assure you that the situation of the frontiers of our county is truly alarming at present, and worthy of our most serious consideration. * * * * * * * * * *"I make no doubt but you will be informed of a campaign that is to be carried against the Indians by the middle of the next month. General Irvine is to command. I have my own doubts."

The following extract from a letter written by General Irvine to Washington on the 27th of January, 1783, (17), shows the origin of the attack upon Hannastown, and that the enemy, came from the "heads of the Allegheny," as Douglass surmised: "In the year 1782, a detachment composed of three hundred British, and five hundred Indians, was formed and actually embarked in canoes on Lake Jadaque [Chautauqua Lake], with twelve pieces of artillery, with an avowed intention of attacking Fort Pitt. This expedition * * * * was laid aside in consequence of the reported repairs and strength of Fort Pitt, carried by a spy from the neighborhood of the fort.

"They then contented themselves with the usual mode of warfare, by sending small parties on the frontier, one of which burned Hannastown."

The following letter was written by General Irvine to William Moore, then President of the Supreme Executive Council. The letter to which he refers was probably the one written by Huffnagle to him under date July 14th, 1782, heretofore given:

"Fort Pitt, July 16, 1782.

"Sir :—Enclosed is a copy of a letter which is the best account I have been able to get of the unfortunate affair related in it."The express sent by Mr. Huffnagle through timidity and other misconduct, did not arrive here till this moment (Tuesday, 10 o'clock), though he left Hannastown Sunday evening, which I fear will put it out of my power to come up with the enemy, they will have got so far if they please; however, I have sent reconnoitering parties to try to discover whether they have left the settlements and what route they have taken.

"I fear this stroke will intimidate the inhabitants so much that it will not be possible to rally them or persuade them to make a stand; nothing in my power shall be left undone to countenance and encourage them. But I am sorry to acquaint your excellency, there is little in my power—a small garrison scantily supplied with provision, rarely more than from day to day, and even at times days without—add to this that, in all probability, I shall be in the course of a few days, left without settlers in my rear to draw succors from. I have not time to add [more], having found a Mr. Elliott who is instantly setting out for Lancaster, from whence he promises to forward this. (17.)

It will be seen from the following extract from a letter of Edward Cook, lieutenant of Westmoreland county, to the governor of Penn'a that he used every expedient to aid those who suffered by the attack upon Hannastown:

"Westmoreland County, September 2, 1782.

"Sir:—It may be necessary to inform your excellency that upon an application made to me by some of the distressed inhabitants of Hannastown and the vicinity thereof, I have allowed them to enroll themselves under the command of Captain Brice and draw rations for two months, upon their making every exertion in their power to keep up the line of the frontiers."The ranging company, consisting of about twenty-two privates and two officers, is stationed at Ligonier for the defense of that quarter." (18.)

In September of 1782, Capt. Hugh Wiley, (doubtless from Cumberland county, sent over the mountains to Irvine), was stationed at Hannastown. On Oct. 4th, 1782, from that place in a letter to the General he says: "Our County Lieutenant, (probably meaning the lieutenant of Cumberland county, Pa.), informed me that our business would be scouting on the frontier, which was the means of our coming out in the most light order that the season would admit of. We have been reasonably well supplied with provisions since a few days after our arrival here; and I keep out a scout of between twenty and thirty men on the frontier. * * * * I enclose you a return of a lieutenant and a few men who came up since as will appear. I have nothing of importance to communicate. Our scouts have made no discoveries, and they are of opinion the coasts are pretty clear of the enemy." (19.)

Hannastown never recovered from its loss. From the fact that the place had never been definitely agreed upon as the permanent seat of justice, its destruction now terminated any expectation of its being favorably considered thereafter. The board of commissioners had never been harmonious. In the fall of 1773, three members of the commission signed a recommendation favoring Pittsburgh. October 3d, 1774, four members signed a recommendation of Hannastown, or as an ultimatum, a site on Brush Run Manor, probably near Harrison City. Again on Aug. 23d, 1783, after the burning of the place, another recommendation of Hannastown was submitted. It was not acted upon, and before any final report was considered, the Assembly had authorized a State road to be made from Bedford to Pittsburgh, on a route through Westmoreland county, two or three miles south of the old Forbes Road; and on this road Greensburg began its existence within a few years after Hannastown was no more. The courts were still held at Hanna's—the last session in Oct., 1786. In the meantime the Commissioners who had been appointed by the Assembly to select a new location for a county seat, had reported in favor of the place, now known as Greensburg, where the first court was held for the January term of 1787.

The site of the town can now only be approximated, as the lots laid out, became merged long ago into the adjoining land. The graveyard used by the first settlers is still enclosed and kept from desecration, as the tenure of the land has fortunately been in persons of liberal and humane sympathies.

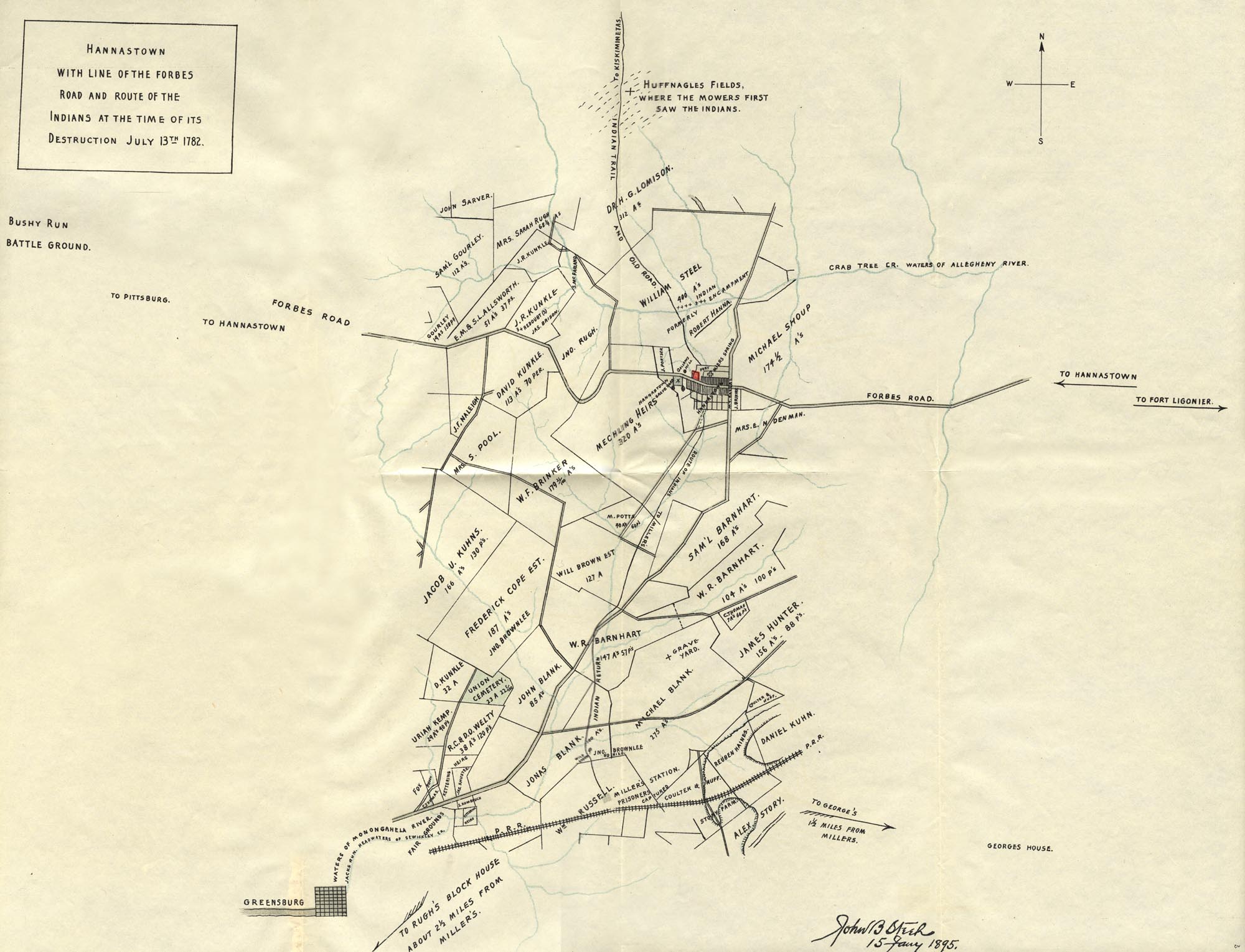

The map accompanying this report has been prepared with much labor and great care under the direction of John B. Steel, Esq., of Greensburg, Pa., especially to illustrate what has been said with respect to this historic place. It shows perhaps as clearly and as certainly as it is possible, (or likely ever will be possible), the proximate points of interest in the old town and in the neighborhood. The spring marked Mier's Spring, a name appearing frequently in old title papers, is located; and so are such places as the site of the fort, the burying-ground, and of Gallow's Hill, which marks the spot where capital punishment was first meted out in these parts to malefactors found guilty by a verdict of twelve jurymen. The route of the marauders as they approached Hannastown, their course to Miller's, the place where Brownlee was killed and where he was buried, their camping-ground on that terrible night and their trail back to the Kiskiminetas, are here laid down.

Beyond these muniments there is nothing to indicate to the stranger the spots made memorable by notable deeds, thrilling associations and marked historical events. And not the least thing to be remembered is the fact that, while the war for the independence of the colonies was practically over, yet this was the last place upon which the British and their savage allies wreaked their vengeance in a common hate. When it is considered how that the project originated in Canada and was carried out in pursuance of orders from the British agents, it may consistently be said that the destruction of Hannastown was the last act of war in the Revolution.

The site of the old town is on the farm now owned by Mr. William Steel, in Hempfield township, Westmoreland county, Pa.

Notes to Hannastown.

(1.) From the encroachments of the whites upon the hunting grounds of the Indians and on the lands not alienated by them, about the years 1767 and 1768, and for various other reasons, there was at this conjuncture many indications that another Indian war was brewing—a war which promised to be a general one. The Indians had been quiet as long as was usual, and their mutterings all round the settlements of the whites from Western New York to Western Virginia were audible. To none was it more instinctively perceptible than to Sir William Johnson, the one man to whom more than to any other the Board of Trade and Plantations intrusted the management of the royal and colonial interests arising from trouble with the tribes. This war was thereupon averted by the intervention of Johnson, whose influence over the Six Nations was unbounded. At his suggestion a great council was held at Fort Stanwix, in New York. Here all grievances were redressed, chains brightened, and tomahawks buried. By the terms of this treaty made with the Six Nations, November 5, 1768, all the territory extending in a boundary from the New York line on the Susquehanna, towards Towanda and Tyadaghton creek, up the West Branch, over to Kittanning on the Allegheny, and thence down the Ohio and along the Monongahela to the Province line, was conveyed to the proprietaries. This was called the New Purchase. Of the most of this region was afterwards erected Bedford and then Westmoreland counties.

The New Purchase, or that of 1768, on our map begins at the Susquehanna in Bradford county; thence, following the courses of those local streams which then were designated by their Indian names, the line meanders in a south and west direction through the counties of Tioga, Lycoming, Clinton, to the northeast corner of Clearfield; passing through Clearfield from the northeast to the southwest corner, it reaches a point at Cherry Tree where Indiana, Clearfield, and Cambria meet; thence in a straight line across Indiana county to Kittanning, on the Allegheny river; thence down the Allegheny to the Ohio, and along the Monongahela till it strikes the boundary line of the State on its southern side.

(2.) John Penn (son of Richard, the grandson of William Penn, born in Phila., 1728, died 1795) was Governor of the Province from 1763 to 1771, and also from 1773 to the end of the proprietary government in 1776.Richard Penn brother of John Penn, was Lieutenant-Governor from 1771 to 1773, during the absence of John Penn in England.

(3.) Arch. iv, 504.

(4.) Arch. Iv, 506.

(5.) St. Clair Papers. Vol. i, p. 353, Arch. Iv

(6.) St. Clair Papers. Vol. i, p. 355, Arch. Iv

(7.) Records xvi, 541.

(8.) Arch. vii, 362.

(9.) Arch. viii, p. 42.

(10.) Arch. Viii, 284.

(11.) Arch. ix, 247.

(12.) Washington-Irvine Cor., p. 381.

(13.) Wash.-Irvine Cor., p. 383.

(14.) Arch. Ix, 596.

The circumstance that Huffnagle's letter to President Moore is dated at Fort Reed has been the source of annoyance to some narrators and the cause of some very erroneous notions. Fort Reed is mentioned in the Twelfth Volume of the Archives on the authority of this letter, and subsequent writers quoting from the Archives have made mention of Fort Reed as a place to which the people of Hannastown fled after the burning of the town. Mr. Darlington in his "Fort Pitt and Letters, etc.," in a list of forts given—it would seem from "Notes by General O'Hara"—quotes: "Fort Reed, erected 1773, near Hannastown." In the list of forts, etc., given with the Historical Map of Penn'a, it is set down with the date 1782. On the Map itself it is placed some distance northward of "Hannastown Stockade," doubtless from the notion that it was "four miles" from Hannastown, a mistake which was likely to occur from a misconstruction of Huffnagle's letter above.

This ambiguity has been rendered more uncertain from the fact that no other mention is elsewhere made of any Fort Reed in those parts, nor is there any such name held in the traditions of the country.It will be borne in mind that at the time the town was burned (except two houses) the fort was not taken. Those cooped up in it remained there until the enemy had left; nor is there any intimation that they had abandoned it at any time thereafter. The letter written by Huffnagle to General Irvine on the day following the attack, was written from "Hannastown." David Duncan on the 30th, (see letter above), speaks only of the fort at Hannastown, saying that "Hannastown * * * * was all reduced to ashes except two houses exclusive of a small fort [Reed?], which happily saved all who were so fortunate as to get to it."

The uncertainty of the language used by Huffnagle in his Fort Reed letter, has, as we say, been the most apparent cause of these mistakes. He states that "at the time this town was attacked, another party attacked Fort Miller, about four miles from this place." We think he meant by the expression "this place," both Hannastown and the Fort there which he calls Fort Reed.

There is no mention of a fort of any sort at Hannastown in 1773, and there is nothing made public from which one can assume that the fort built there in 1774 was called Fort Reed. (Archives, iv, 506, 3d June, 1774.) The name Fort Reed could be applicable in a fitting sense only to the Revolutionary fort, the one which was erected in-the-new, or which was the old one rehabilitated, as we have seen, in 1777. Being a very important post it took its name, probably at the instance of Huffnagle then very active in affairs, in compliment to Joseph Reed, President of the Supreme Executive Council from 1778 to 1781. As Reed was not of the Council in 1782, it may be inferred that it was known locally but not generally as Fort Reed from 1779.

There was a Reed's Blockhouse and Station on the Allegheny river which was noticeable during the Indian troubles after the Revolution. This place was not in the vicinity of Hannastown, and is not to be considered in this connection. We give some account of Reed's Station further on.

A theory sometimes advanced was thought to be tenable, which was that Fort Reed was but a mistaken reading of Fort Rook and applicable to Rugh's Blockhouse. Huffnagle had spoken of "Rook's Blockhouse," (see Rugh's Blockhouse) in a letter of Dec. 20th, 1781. This point, beyond doubt, was one of activity in the days following the raid on Hannastown. It was about the same distance from Miller's. Hence an inference was raised that Huffnagle had intended to write "Fort Rook" and that his writing was made to appear as "Fort Reed."

From these considerations it is a reasonable supposition— and to us conclusive—that the Hannastown fort was the one which Huffnagle calls Fort Reed.

(15.) Wash.-Irvine Cor.

(16.) Arch. Ix, 606.

(17.) Wash.-Irvine Cor.

(18.) It has been said on behalf of Genl. Irvine that he advanced money and material aid to Huffnagle and others on account of the condition of these people. The following voucher would appear to confirm this:

"Fort Pitt, August 22, 1782.

"Received and borrowed from Brigadier General William Irvine, one hundred and thirty-two pounds and eight shillings, specie (money belonging to the State of Pennsylvania), which we promise to pay to General Irvine the first day of October next or bring an order from [the supreme executive] council [of Pa.] on him for that sum.

"MICH. HUFFNAGLE,

"DAVID DUNCAN."From General Irvine's papers, edited by C. W. Butterfield, Esq., and frequently referred to here.

(19.) Wash.-Irvine Cor. , 399.

Extracts from newspapers of 1782, relative to the attack on Hannastown:

[I.] "Philadelphia, July 30. From Westmoreland county, 16 July. On the 13th a body of Indians came to and burnt Hannastown, except two houses. The inhabitants having received notice of their coming, by their attacking some reapers who were at work near the town, fortunately (except fifteen who were killed and taken) got into the fort, where they were secure. [Pennsylvania Packet, 80 July, 1782, No. 917.

[II.] "Richmond, Aug. 17. By our last accounts from the northwestern frontier we learn that the Indians have lately destroyed Hannastown and another small village on the Pennsylvania side, and killed and captured the whole of the inhabitants." [Pennsylvania Packet, 27 Aug.. 1782. [No. 929.]

[III.] "Extract of a letter from Fort Pitt, dated Sept. 3: ‘From the middle to the last of July, the Indians have been very troublesome on the frontiers of this country—Hannastown was burned, several inhabitants killed and taken, and about the same time Fort Wheeling [Henry] was blockaded for several days; for two weeks the inhabitants were in such consternation, that a total evacuation of the country was to be dreaded [feared] but since the beginning of August matters have been more quiet, and the people have again, in a great degree, got over their panic. " [Pennsylvania Packet, 1 Oct., 1782, No. 944; Salem Gazette, Oct. 17, 1782.]

Guyasutha, or Kiashuta as the name is more frequently spelled in the old Records, and which spelling probably corresponds more nearly with the true pronunciation—was the leading spirit of the Senecas in this part of the country, and was one of the most blood-thirsty and powerful chiefs of his time. The following sketch is by Neville B. Craig, Esq. It is of course very inadequate, but no biography of him has been attempted at any other hand.

"That ubiquitous character (whose name is so variously spelt Guyasoota, Keyasutha, Guyasotha, Kiashuta, and various other names), who long acted a conspicuous part near the Ohio, was at the treaty with Bradstreet, and afterwards was a leading actor in the conference with Bouquet.

"He was certainly a very active leader among the warriors of the Six Nations. The first notice we have of him is in Washington's journal of his visit to Le Boeuf, in 1753. The name does not appear in that journal, but Washington mentions in the diary of his visit to the Kenawha in 1770 that Kishuta called to see him while he was descending the Ohio, and then states that he was one of the three Indians who accompanied him to Le Boeuf. He was afterwards, as we have before stated, one of the deputies at the treaties with Bradstreet and Bouquet. In 1768, he attended a treaty in this place, of which we will give a full account. He was, we understand, the master spirit in the attack upon and burning of Hannastown.

"The war of 1764 has sometimes been spoken of as Pontiac, and Guyasootha's war.

"We recollect him well, have often seen him about our father's house, he being still within our memory, a stout active man. He died, and was buried, as we are told, on the farm now owned by James O'Hara, called "Guyasootha's Bottom." (Olden Time, Vol. i, 337.)

In the History of Venango county, (compiled and published by Brown, Bunk & Co., Chicago, Ill., 1890) it is said: "Guyasutha was one of the most prominent of all the Indians sachems on the Allegheny. He was a man of great ability and good judgment, an implacable enemy, and a firm friend. In his youth he accompanied Washington in his trip to Venango, and is probably known in his Journal as "The Hunter." We find him on all occasions and in all places, in times of peace, and in times of war. He had been the great leader in the burning of Hannastown, and in other operations at that time."

Two places dispute the honor of his burial-place. Mr. Craig, as we have seen, locates the place of his sepulture in Allegheny county, but some have contended that he died and was buried at Custaloga's town, a town of the Senecas on French creek, some twelve miles above its mouth and near the mouth of Deer creek.

In respect to the burial of Guyasutha, at Custaloga's town, the late Charles H. Heydrich, a few years before his death, wrote as follows:

"Early in the present century, my father, the late Dr. Heydrick, made a tour of inspection of these lands and found evidences of occupation by the Indians, and other vestiges of the Indian village being still visible. At that time there was living upon an adjoining tract a settler named Martin, who had settled there soon after the remnant of land north and west of the Rivers Ohio and Allegheny and Conewango creek, not appropriated to Revolutionary soldiers, etc., had been thrown open to settlement—certainly as early as 1798. One of Martin's sons, called John, Jr., was a bright, and for the time and under the circumstances, an intelligent young man, and claimed to have been intimate with the Indians, and spoke their language.

"In 1819 I first visited the place, and stopped at Martin's house, while there I found many vestiges of the Indian village, and made many inquiries of its people. In answer to my inquiries John Martin, Jr., told me, among other things, that he had assisted in the burial of three Indians on my farm, an idiot boy, "Chet's" squaw, and a chief whose name he pronounced "Guy-a-soo-ter." He said that he made the coffin for "Guyasooter," and after it was finished the Indians asked him to cut a hole in it in order that he ("Guyasooter") might "see out." He farther said that "they buried all his wealth with him; his tomahawk, gun and brass-kettle." Martin pointed out to me the grave of the chief, and the spot was always recognized as such by the other pioneers of the neighborhood, though I do not remember that any of them except Martin professed to have witnessed the burial. * * * From all the evidence I had on the subject, much of which had doubtless escaped my recollection, and some of which was probably derived from other sources than Martin, I was so well satisfied that the chief named and others were buried at the place designated by Martin that I have to this day preserved a grove about the reputed graves, and have had it in mind to mark the spot by some permanent memorial."

James M. Daily, a pioneer of French Creek township, Mercer county, whose farm adjoined those of Heydrick and Martin and who was a resident of that locality from 1804 until his death, made the following statement regarding the burial of Guyasutha under date of June 15, 1878:

"John Martin, Jr., who could converse in the Indian tongue, informed me that he made the coffin and assisted in burying a chief. They placed in the coffin his camp-kettle, filled with soup; his rifle, tomahawk, knife, trinkets, and trophies. I think they called him ‘Guyasooter.'" (Id., p. 28.)

MILLER'S STATION.

Miller's Station, or Miller's Fort as it is sometimes called, attained celebrity at the time of the incursion of the Indians when Hannastown was destroyed. Captain Samuel Miller was a prominent settler at that place as early as 1774, his name appearing among petitions of that year to Governor Penn. He was one of the eight Captains of the Eighth Penna. Regiment in the Continental Line; was ordered from Valley Forge, Feb. 10th, 1778, to Westmoreland county, on recruiting service, and while here was killed, July 7th, 1778. (Arch. vi, 673.)

Throughout 1781-2 the Miller homestead was resorted to by many of the surrounding people, a fact attested by the most authentic account of the destruction of Hannastown, that has been preserved. (See Hannastown.) There does not appear, however, to have been any blockhouse or other structure suitable for warfare erected at this place. It is probable that there were ample accommodations in cabins temporarily erected for those who were there at that time. On the day when Hannastown was attacked and burned, Miller's Station was also attacked and many prisoners were taken. In the account which is given herewith of the destruction of Hannastown, the particulars of the attack on Miller's Station will be found also.

It will be seen from the copy of a paper which we give below that reference is made to the character of the building at the time of its destruction. The paper appears to have been a deposition made by the Hon. William Jack in some contested title arising out of the ownership of the old Miller farm. It was used apparently in evidence, but is no part of the records. The writing is in Judge Jack's own hand:

"Westmoreland county, S. S. Before me, a Justice of the Peace in and for said county of Westmoreland, personally appeared William Jack, Esq., who was duly sworn according to law, did depose and say that Captain Samuel Miller, who was killed by the Indians in the year 1778, at the commencement of the Revolutionary War, actually settled on a plantation now adjoining Peter Eichar, John Shoeffer, John Mechling, and others in Hempfield township in the county aforesaid, that Andrew Cruikshanks (who married the Widow of the said Captain Samuel Miller), Joseph Russell, who is married to one of the Daughters of the said Samuel Miller, dec'd, claims the benefit of an act of Assembly passed September 16, 1785, and that the said Andrew Cruikshanks was in the course of the said war actually in possession of the said plantation, and was drove away from his habitation on said land by the Indians on the 13th day of July, A. D. 1782, being the same day that Hannastown was burned and destroyed by the Indians, and that, some of the heirs of the said Captain Samuel Miller was killed and taken prisoners on the said day, and that the House was burned and the property in the House by the Enemy, and that afterwards the said Plantation lay waste and vacant for some time for fear and dread of the Indians.

"WM. JACK."Sworn & subscribed before me the ninth day of March, A. D. 1814. R. W. Williams. (J. P.)"

The location of the Miller house was on the farm known the William Russell farm, in Hempfield township, Westmoreland county, about two miles northeast of Greensburg,not far from the Pennsylvania railroad, on the northern side—within probably half a mile of the railroad.

FORT HAND.

Fort Hand was erected near the house of one John McKibben, whose "large log house" had been the refuge and asylum of a number of people whither they had fled at times preceding that event, as is noted in the sketch of Carnahan's Blockhouse. From the extract given there from the Draper Manuscripts, now in possession of the Wisconsin Historical Society, it appears that during the summer of 1777, when the Indians infested all that line of frontier, McKibben's house was one of the objective places, at which many families remained probably during the entire summer while the men gathered the crops and scouted and fought. Carnahan's Blockhouse was the nearest point; and although they were only about three or four miles apart the communication between them was frequently cut off.

This portion of Westmoreland—and of the frontier as well— would have been entirely deserted that summer, so much did it suffer from the savages, had not Colonel Lochry succeeded in raising sixty men whom he stationed in four divisions under command of two captains and two lieutenants, and who covered the line of the Kiskiminetas. (1.) A part of this force ranged this neighborhood and assisted the inhabitants from these two posts—Carnahan's and McKibben's.

McKibben's house, and subsequently Fort Hand, were from three to four miles south from the Kiskiminetas river at the ford, and the ford was about six miles above the mouth of the stream. The stream was northwest from Hannastown about fourteen miles.

Upon the particulars mentioned in the Draper Manuscripts, which were founded on the statement of James Chambers who was personally conversant with the facts, the reapers in the oat field, when they had been apprised of the presence of Indians, left to notify the people, taking their guns with them and "going to the house of John McKibben's where Fort Hand was made the ensuing winter, and where several families had collected for safety in McKibben's large log house."

The exact date of the erection of Fort Hand is not known, but it was sometime in the fall of that year for it was occupied and had its name, (after Col. Hand), at least early in the winter.

On the 6th of December, 1777, Col. Lochry in a letter to President Wharton, after reciting the privations and dangers of the people from their exposed situation by reason of having sent some of his men to General Hand for the proposed expedition which the General had contemplated, says that there is "not a man on our frontiers from Ligonier to the Allegheny river, except a few at Fort Hand, on continental pay." (2.)

General (then Col.) Hand to Lochry, on the 18th of Oct. 1777, says—"Congress ordered a post in your county (The Kittanning); I could not support that and have ordered another to be erected at the expense of the Continent. This I think sufficient, and will support, if you lend me your aid; at the same time, beg leave to assure you that I don't mean to interfere with your command of Westmoreland county, or in your plan in erecting as many forts and magazines as you please at the expense of the State of Pennsylvania, and putting the whole county in its pay. * * * * I shall to-morrow proceed to Wheeling with what troops I have; yours will receive every necessary I can afford them when they arrive here, [Fort Pitt] and when they join me shall be put on the same footing with the militia of any other county." (3.) The expedition to Wheeling was abandoned when it was found that not a sufficient number of men could be collected that season to enter the Indian country.

March 22d, 1778, Gen. Hand writes to Col. Lochry: "I am instructed by the Hon., the Commissioners appointed by Congress to fix on a plan for the defence of these frontiers, to desire that you may continue a hundred and fifty privates of the militia of your county, properly officered, on constant duty on its frontiers. Thirty of them to be added to Capt. Moorhead's company, stationed at Fort Hand, and the remaining one hundred and twenty placed at such stations as you will find best calculated for the defence of the county." (4.)

Capt. Moorhead and Col. Barr had been in the service of the militia raised by Westmoreland, from the summer preceding; they reported to Gen. Hand for service in the project against Wheeling.