REPORT OF THE COMMISSION TO LOCATE THE SITE OF THE FRONTIER FORTS OF PENNSYLVANIA.

VOLUME TWO.

CLARENCE M. BUSCH.

STATE PRINTER OF PENNSYLVANIA.

1896.

THE FRONTIER FORTS OF WESTERN PENNSYLVANIA.

FORT PITT

(Pages 99-159)

Numbered notes found in section on Fort Fayette.

Thus at last this point of land which had been the cause of the loss of many lives and of much treasure, fell into the hands of the English; and again the cross of St. George flew over the spot where the fleur-de-lis of St. Louis had floated for four tempestuous years.

General Forbes in reporting to Governor Denny immediately after his taking possession, says:

As the conquest of this country is of the greatest consequence to the adjacent provinces, by securing the Indians our real friends for their own advantage, I have therefore sent for their head people to come to me, when I think, in few words and in few days to make everything easy.

I shall be obliged to leave about 200 men of your provincial troops to join a proportion of Virginians and Marylanders, in order to protect this country during winter, by which time I hope the provinces will be sensible of the great benefit of this new acquisition, as to enable me to fix this noble, fine country to all perpetuity under the dominion of Great Britain.

I beg the barracks may be put in good repair and proper lodging for the officers, and that you will send me with the greatest despatch, your opinion how I am to dispose of the rest of your provincial troops; for the ease and convenience of the provinces and inhabitants. Your must also remember that Col. Montgomery's battalion of 1,304 companies of Royal Americans, are, after so long and tedious campaign, to be taken care of in some winter quarters. (61.)

The name for the fortification which it was intended to build after the place was secured, had been determined upon before that event occurred. With one accord the name of Fort Pitt as applied to the intended fort. Pittsburgh, as the name of the place, appeared the next day after its occupancy. On November the 26th, Forbes in reporting the capture of the place to Lieutenant-Gov. Denny, in the letter which we have already quoted, dated it from Fort Duquesne, "or now Pitts-Bourgh." (62.)

It is a noticeable circumstance that in the correspondence which appears in the Penna. Gazette, and in official communications bearing date at this place, not only during its occupancy as an English outpost and later as the most important place in Western Pennsylvania during colonial times, and then as headquarters of the Western Department during the Revolution, the name of the place, "Pittsburgh." was used more frequently than that of Fort Pitt. (63.)

Gen. Forbes immediately began the erection of a new fort near the site of the old one. The work was proceeded in with all possible activity. It was getting late in the season. The enemy had withdrawn, it is true, but their whereabouts were not definitely known. Most of them had gone up the river to Fort Machault; some of them had gathered at the strong-hold at Loggstown, down the Ohio. The post was watched by spies and Indians, and thus the situation was not one of absolute confidence or security.

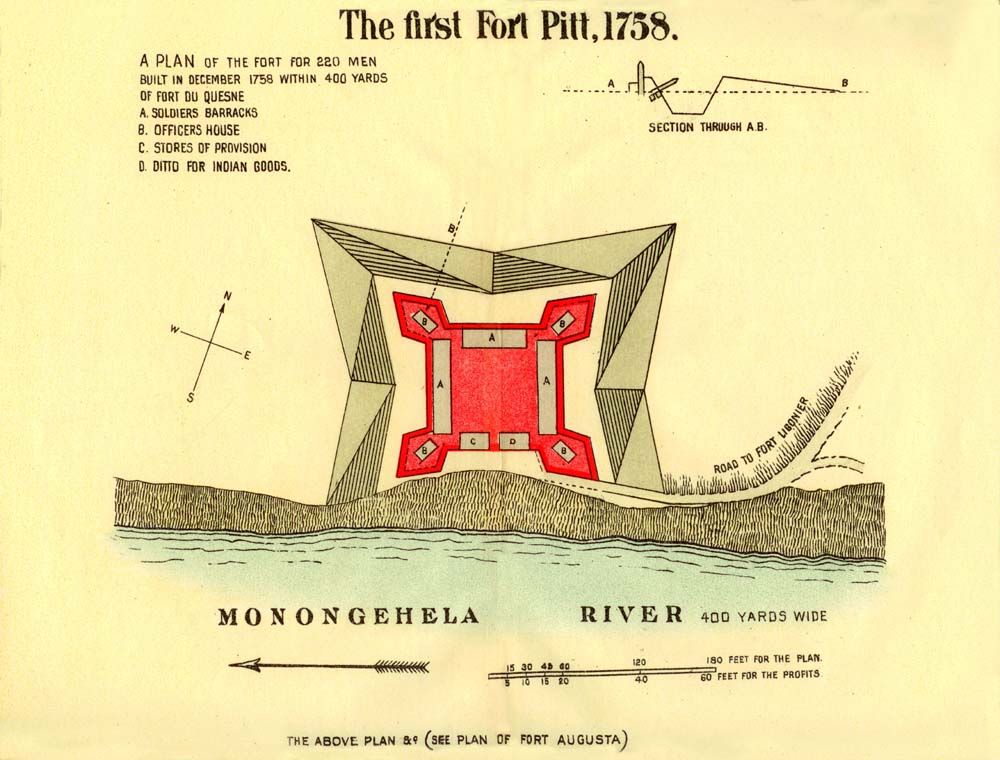

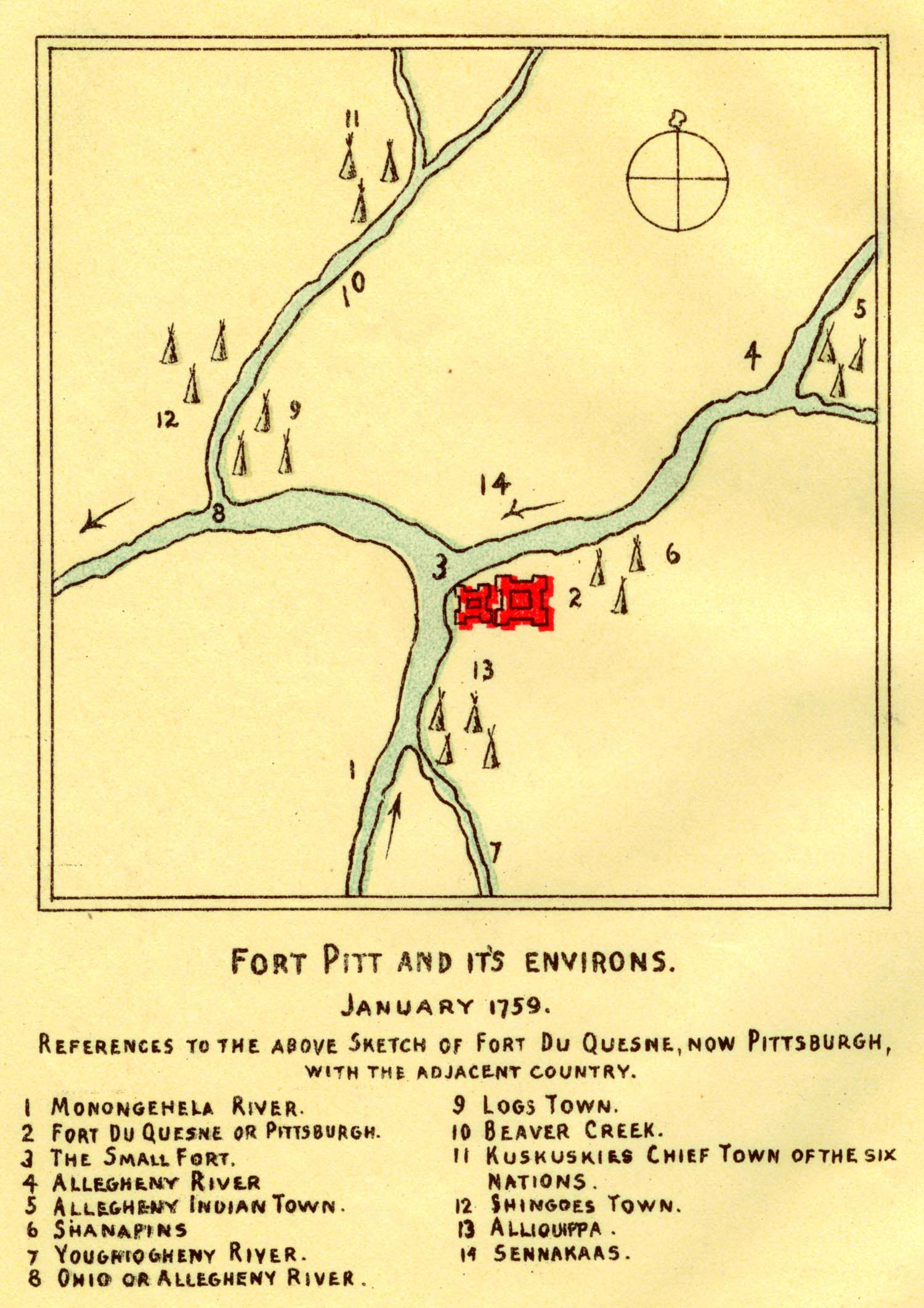

The character of the structure and the location of the new fort were probably determined upon before Forbes left on his return for Philadelphia, which he did on the 3d of December. The work was located on the bank of the Monongahela at the south end of what, later, was West street in the city of Pittsburgh, and between West street and Liberty, within 200 yards of Fort Duquesne. It has been described as "a small square stockade, with bastions." (64.) It was intended only for temporary use, and for the present accommodation of a garrison of 200 men. With this number, when it was completed, Col. Hugh Mercer, was placed in command; and the army marched back to the settlements.

The fort, so called, was completed probably about the first of January, 1759. Col. Mercer, under date of January 8, 1759, reported the garrison to consist then of about 280 men, and that the "works" were capable of some defense, though huddled up in a very hasty manner, the weather being extremely severe. (65.)

On March the 17th, 1759, the garrison is reported as follows: There were 10 commissioned officers, 18 non-commissioned officers, 3 drummers, 346 rank and file, fit for duty, 79 sick, three (unaccounted) making a total of 428. Twelve had died since the 1st of January. In respect of their commands, they were divided as follows: Royal artillery, 8; Royal Americans, 20; Highlanders, 80; Virginia regiment, 99; First Batt'n Penna., 136; Second Batt'n Penna., 85.

Between the one-fifth and one-sixth of the force, were sick. (66.)

On July the 9th, 1759, the officers at the place were the following: Colonel Hugh Mercer; Captains Waggoner, Woodward, Prentice, Morgan, Smallman, Ward and Clayton; Lieutenants Mathews, Hydler, Biddle, Conrod, Kennedy, Sumner, Anderson, Hutchins, Dangerfield and Wright of the train; Ensigns Crawford, Crawford and Morgan.

This structure, as stated, was intended for temporary use only. The one to succeed it was intended to be an imposing fortress and such as would last for all time. Work was expected to be begun upon it within the coming year. General Forbes having died, March 13th, 1759, shortly after his return to Philadelphia, was succeeded by General John Stanwix as commander of His Majesty's regular troops, and those to be raised by the Provinces, for the Southern Department. The announcement of the appointment of Stanwix and of the death of Forbes, was made by Gen. Amherst, Commander-in-Chief, on the 15th of March, 1759.

The importance of this post as it appeared to the great William Pitt, after whom the fort and the succeeding city, were called, is manifest from an expression of his opinion in a letter dated at Whitehall, Jan. 23d, 1759, just 60 days after the taking of Fort Duquesne. The letter shows also the intention of the Ministry. (67.)

"I am now to acquaint you," says he, "that the King has been pleased, immediately upon receiving the news of the success of his arms on the river Ohio, to direct the Commander-in-Chief of his Majesty's forces, in North America, and Gen. Forbes, to lose no time in concerting the proper and speediest means for completely restoring if possible, the ruined Fort Duquesne to a defensible and respectable state, or for erecting another in the room of it of sufficient strength and every way adequate to the great importance of the several objects of maintaining his Majesty's subjects in the undisputed possession of the Ohio; of effectually cutting off all trade and communication this way, between Canada and the western and southwestern Indians; of protecting the British colonies from incursion of which they have been exposed since the French built the fort and thereby make themselves masters of the navigation of the Ohio, and of fixing again the several Indian nations in their alliance with and dependance upon his Majesty's government."

Gen. Amherst having received instructions of a like tenor from Secretary Pitt, acquainted the Governor of the fact, and requested the cooperation of the Province with Stanwix to that end. (68.)

During the early summer of 1759, the greatest apprehension was felt on account of the project which the French had in view, of descending from Fort Machault for an attack on Fort Pitt. A large force was collected there, which, if circumstances had not intervened to divert their operations, would probably have been adequate to capture the place. But the urgent necessity of the French at Niagara, which place was invested by the English, compelled them to abandon their project. (69.)

General Stanwix, soon after his appointment as the Commander of this department, arranged to go to Fort Pitt, and there begin the construction of a permanent fortification, and such a one as would be a credit to his government, and insure a permanent defense of the province in those parts. He had, however, much trouble with the Pennsylvania authorities to get what he regarded as the necessary supplies and a sufficient number of men and artificers. The season was going by, and he was becoming impatient From his camp at Fort Bedford, the 13th of August, 1759, he wrote to Governor Denny. (70.)

"It is with reluctance that I must trouble you again upon this subject, but being stopped in my march, for want of a sufficient and certain succession of carriages, I am obliged to have recourse to you to extricate me out of this difficulty."

At the same time he addressed a circular letter to the managers for wagons in each county, say, in part (71):

"The season advances fast upon us, and our magazines are not half full. All our delays are owing to want of carriages. The troops are impatient to dislodge and drive the enemy from their posts on this side of the Lake, and by building a respectable fort upon the Ohio, secure to his Majesty the just possession of that rich country."

Around the garrison at this time many Indians had collected who were now the dependants of the English, being brought thither upon invitations to attend conferences and councils, of which there had been several since the English occupancy of the place. The treaty of July, 1759, was attended by great numbers. These had to be fed, nor did they show indication of departing so long as there was sufficiency of provisions. Col. Mercer complains, on the 6th of August, 1759, (72) that on account of this drain upon their supplies, the garrison had been brought to great straits, and he had been obliged to reduce the garrison to 350, and even with that number, could scarcely save an ounce between the convoys. On the same date Mercer reports that Captain Gorden, chief engineer, had arrived, with most of the artificers, but that he would not fix on the spot for constructing the fort until the arrival of the General, but that they were preparing the materials for building with what expedition so relatively few men were capable of.

General Stanwix arrived at Pittsburgh, late in August, 1759, with materials, skilled workmen and laborers, for the purpose, and on the 3d day of September, the work of building a formidable fortification commenced, in obedience to the orders of William Pitt, Secretary of State.

Colonel Mercer reports September 15th, 1759:

"A perfect tranquility reigns here since General Stanwix arrived, the works of the new fort go on briskly, and no enemy appears near the camp or upon the communication. The difficulty of supplying the army here, obliges the General to keep more of the troops at Ligonier and Bedford than he would choose; the remainder of the Virginia regiment joins us next week. Colonel Burd is forming a post at Redstone Creek, Col. Armstrong remains some weeks at Ligonier, and the greater part of my battalion will be divided along the communication to Carlisle." (73.)

Gen. Stanwix to Governor Hamilton in a letter dated "Camp at Pittsburgh, 8th December, 1759," (74) reports that "the works here are now carried on to that degree of defense which was at first prepared for this year, so that I am now forming a winter garrison which is to consist of 300 provincials, one-half Pennsylvanians the other Virginians, and 400 of the first battalion, of the Royal American regiment, the whole to be under the command of Major Tulikens when I leave it. These I hope I shall be able to cover well under good barracks and feed likewise, for 6 months from the first of January; besides artillery officers and batteaux men, Indians too must be fed, and they are not a few that come and go and trade here and will expect provisions from us, in which, at least at present they must not be disappointed."

Gen. Stanwix remained at Fort Pitt until the spring of 1760. In the fall of 1759 was held a conference with the Indian which was most satisfactory in its results. It was the policy of the English government, in which it was seconded by the Provinces of Pennsylvania and Virginia, that the officers of the army as well as the authorities of the Provinces should use every effort to conciliate the Indians and keep them on good terms. Accordingly, Colonel Bouquet, representing Forbes, with Col. Armstrong and several officers, George Croghan, Deputy agent to Sir Wm. Johnson, with Henry Montour, as interpreter met with the chiefs of the Delaware Indians at Pittsburgh, on December 4th, 1758, after their occupancy of the post. At this meeting the Indians were assured of the peaceful intentions of the King of England and his people toward them. (75.)

Col. Mercer in January (3d-7th), 1759, held a conference with nine chiefs of the Six Nations, Shawanese and Delawares, from the upper Allegheny, (76) and a very important conference was held here in July, beginning on the 4th, (1759), by George Croghan, Esq., Deputy Agent to Gen. Sir. Wm. Johnson, Bart., his Majesty's Agent and Superintendent for Indian Affairs in the Northern District of North America, with the Chiefs and Warriors of the Six Nations, Delawares, Shawanese, and Wyandottes, who represent eight nations, Ottawas, Chipawas, Potowatimes, Twightwees, Cuscuskees, Keckepos, Schockeys, and Musquakes. (77.)

Here, General Stanwix met the representatives of the Six Nations, Shawanese, Delawares and other Indian tribes, on the 25th of October, 1759. There were present on the part of the English, Brig.-Gen. Stanwix, with sundry gentlemen of the army; George Croghan, Esq., Deputy Agent to Sir William Johnson; Captain William Trent and Captain Thomas McKee, Assistants to George Croghan; Captain Henry Mountour was interpreter. At these various conferences the Indians were represented by their prominent chieftains, of whom may be mentioned, Guyasuta, The Beaver, King of the Delawares, Shingas, the Pipe, Gustalogo, and Killbuck. (78.)

Many private conferences were held to which the Indians came in and promised to be eternal friends with the whites. The Indians, indeed, never hesitated to come when they wanted something to eat and drink, and a supply of ammunition and blankets.

General Stanwix to Governor Hamilton from Fort Pitt, March 17th, 1760, says (79): "As soon as the waters are down I propose to leave this post for Philadelphia, which I can do now with great satisfaction, having finished the works all round in a very defenseable manner, leave the garrison in good health, in excellent barracks, and seven months wholesome good provisions from the 1st of April next; the rest of the works may be now finished under cover, and [the men] be only obliged to work in proper weather, which has been very far from our case this hard winter and dirty spring–so far as it is advanced–but we have carried the works as far into execution as I could possibly propose to myself in the time, and don't doubt but it will be finished as soon as such work can be done, so as to give a strong security to all the Southern Provinces, and answer every end proposed for his Majesty's service."

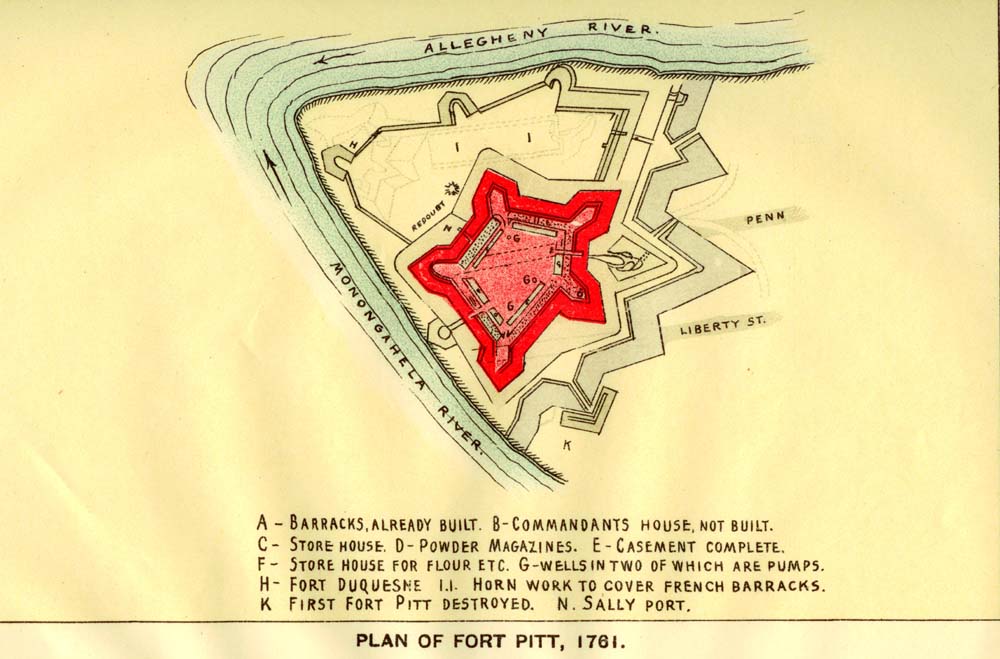

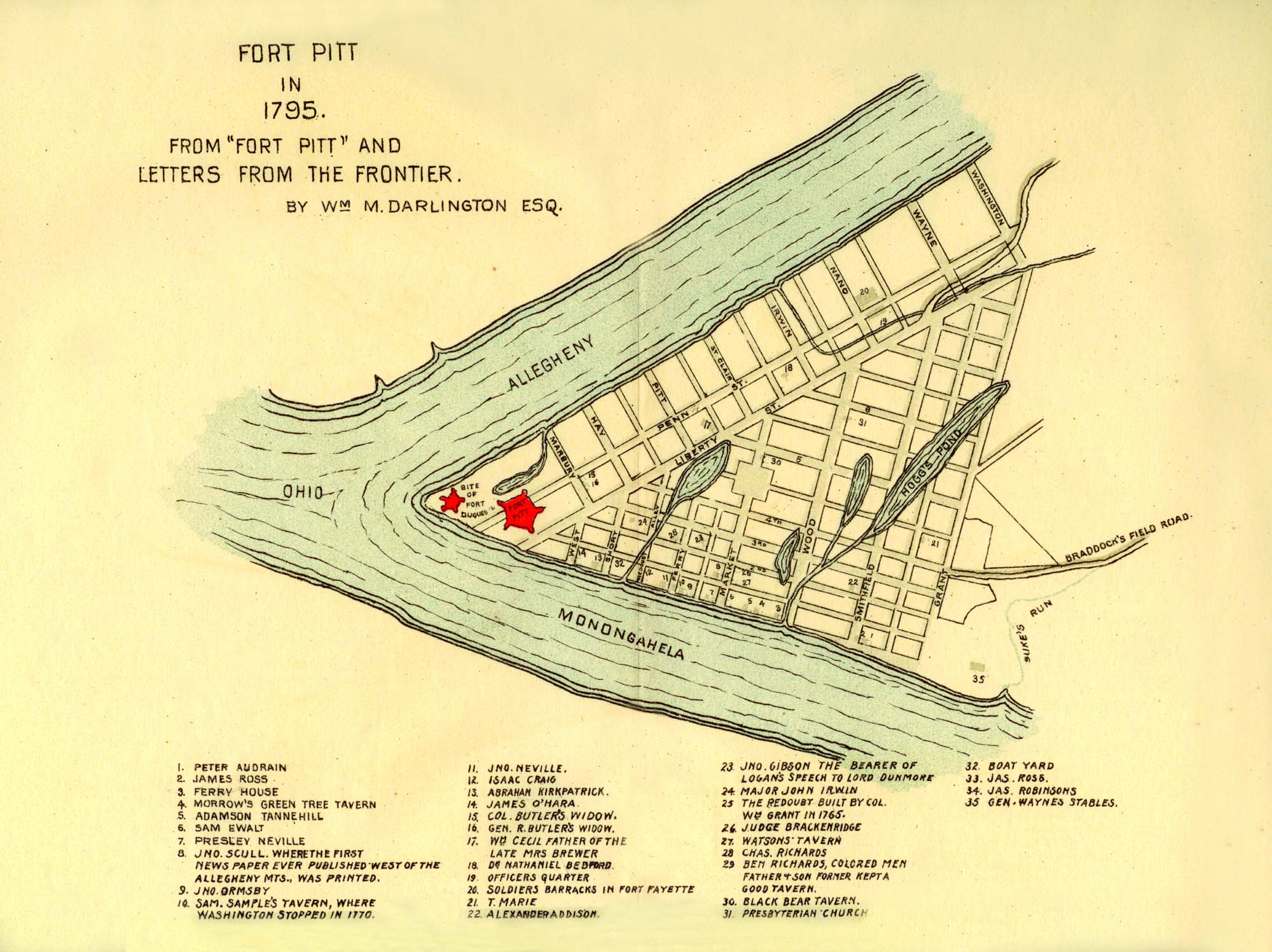

Although Fort Pitt was occupied in 1760, it was not finished until the summer of 1761 under Col. Bouquet. It occupied all the ground between the rivers, Marbury (now Third street), West street, and part of Liberty. Its stone bomb-proof magazine was removed when the Penna. Railway Company built its freight depot in 1852. (80.)

"The work," says Neville B. Craig, (81) "was five sided, though not all equal, as Washington erroneously stated in his journal in 1770. The earth around the proposed work was dug and thrown up so as to enclose the selected position with a rampart of earth. On the two sides facing the country, this rampart was supported by what military men call a revetment–a brick work, nearly perpendicular supporting the rampart on the outside, and thus presenting an obstacle to the enemy not easily overcome. On the other three sides, the earth in the rampart had no support, and, of course, it presented a more inclined surface to the enemy–one which could be readily ascended. To remedy, in some degree, this defect in the work, a line was fixed on the outside of the foot of the slope of the rampart. Around the whole work was a wide ditch which would, of course, be filled with water when the river was at a moderate stage.

"In summer, however, when the river was low the ditch was dry and perfectly smooth, so that the officers and men had a ball-alley in the ditch, and against the revetments.

"This ditch extended from the salient angle of the north bastion–that is the point of the fort which approached nearest to Marbury street, back of the south end of Hoke's row–down to the Allegheny where Marbury street strikes it.

"This part of the ditch was, during our boyhood, and ever since, called Butler's Gut, from the circumstances of Gen. Richard Butler and Col. Wm. Butler residing nearest to it–their houses being the same which now [1848] stand at the corner on the south side of Penn and east side of Marbury. Another part of the ditch extended to the Monongahela, a little west of West street, and a third debouche [opening] into the river was made just about the end of Penn Street.

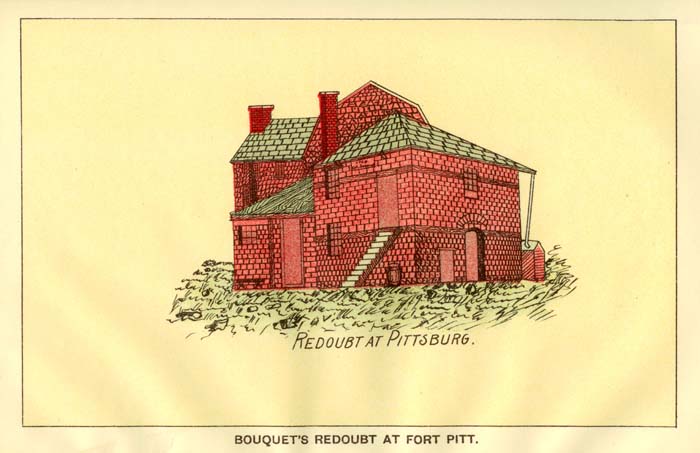

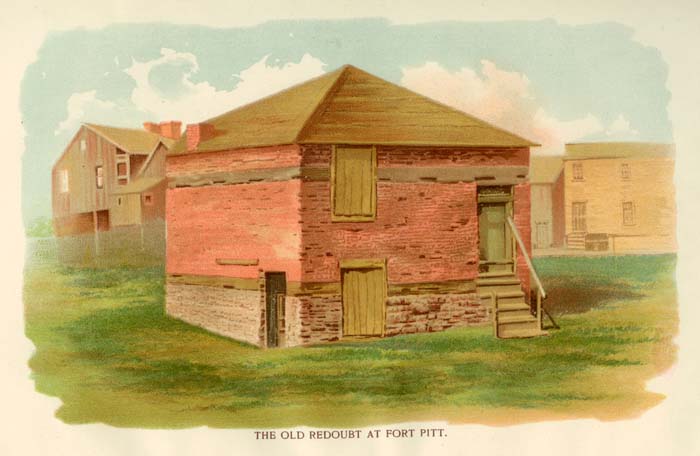

Bouquet's Redoubt at Fort Pitt.

The drawing of the Redoubt is from Day's Historical Collections of Pennsylvania. It is there said that it is a "view as it now (1843) appears. In looking at the drawing, the reader should understand that the Redoubt is merely the square building in front. It is situated north of Penn Street, about 46 feet west of Point Street, a few back from Brewery Alley."

The Redoubt in the above drawing is shown from another point of view than the drawing of current date. The windows, the steps, and at least the door to the left, are to be taken as modern innovations.

"The redoubt, which still remains near the point, the last relic of the British labor at this place, was not erected till 1764. The other redoubt, which stood at the mouth of Redoubt Alley, was erected by Col. Wm. Grant; and our recollection is, that the year mentioned on the stone tablet was 1765, but we are not positive on that point."

Gen. Stanwix remained at Pittsburgh until March 21st, 1760. From a communication dated from the fort at Pittsburgh, on that date, and printed in the Penna. Gazette as part of the current news, the following information is obtained:

"This day Major-Gen. Stanwix set out for Philadelphia, escorted by 35 chiefs of the Ohio Indians and 50 of the Royal Americans. The presence of the General has been of the utmost consequence at this post during the winter, as well for cultivating the friendship and alliance of the Indians, and for continuing the fortifications and supplying the troops here and on the communications. The works are now quite perfected, according to the plan, from the Ohio to the Monongahela, and 18 pieces of artillery mounted on the bastions that cover the isthmus; and case-mates, barracks and store-houses are also completed for a garrison of 1000 men and officers, so that it may now be asserted with very great truth, that the British dominion is established on the Ohio. The Indians are carrying on a vast trade with the merchants of Pittsburgh, and instead of desolating the frontiers of these colonies, are entirely employed in increasing the trade and wealth thereof. The happy effects of our military operations are also felt by [many] of our poor inhabitants, who are now in quiet possession of the lands they were driven from on the frontiers of Pennsylvania, Maryland and Virginia.

"When Gen. Stanwix left Fort Pitt there were present as a garrison 700, namely, 150 Virginians, 150 Pennsylvanians and 400 of the First Battalion of Royal Americans." (82.)

The war between England and France having terminated to the advantage of the English by the surrender of Montreal, the last post held by the French, on 8th of September, 1759, the English in the fall of 1759 and in 1760 took possession of the surrendered posts.

General Monckton, as the chief officer of this department, arrived at Fort Pitt on the 29th of June, 1760. Immediately on his arrival he gave orders for the march of a large detachment of the army to Presqu' Isle, (now Erie). This movement was made for the purpose of taking possession of the upper posts as well as those along the frontier to Detroit and Mackinaw. On the 7th of July, 1760, four companies of the Royal Americans, under command of Colonel Bouquet, and Captain McNeil's company of the Virginia Regiment, marched for Presqu' Isle. These were followed in a few days after by Col. Hugh Mercer, with three companies of the Penna. Regiment, under Captains Biddle, Clapham and Anderson, and later two other companies of the same regiment, under Captains Atlee, and Miles, followed.

A news item dated from Philadelphia the 31st of July, 1760, gave information that Maj. Gladwin had arrived at Presqu' Isle with 400 men from the northward, and that our troops from Pittsburgh would be at the same place by the 15th July, 1760. (83.)

The town of Pittsburgh began, in all probability, with the occupancy of the place by the English in the fall of 1758. That is to say that from the first there was, near the fort, a collection of rude cabins occupied by traders, purveyors of the army and settlers. The name of the town, we have seen, was contemporary with the name of the fort. The mention made of the town by Col. James Burd in his Journal is probably the first authentic mention with regard to its inhabitants, available. Col. Burd in command of the Augusta Regiment–as the Penna. Regiment under his command was then called– arrived at Pittsburgh on Sunday, 6th July, 1760, and remained there on the duty until November following. In his Journal is the following (84):

"21st, Monday. [July, 1760.]

Today numbered the Houses at Pittsburgh, and made a Return of the number of People–men, women and children–that do not belong to the army:

| Number of houses | 146 |

| Number of unfinished houses | 19 |

| Number of Huts | 36 |

| Total | 201 |

| Number of Men | 88 |

| Number of Women | 29 |

| Number of Male Children | 14 |

| Number of Female Children | 18 |

| Total | 149 |

"N. B.–The above houses Exclusive of those in the Fort; in the fort five long barricks and a long casimitt [casement]."

During the winter of 1760 and 1761, Col. Vaughan, with the regiment, known as his Majesty's regiment of Royal Welsh Volunteers, were garrisoning the several posts within the communication to Pittsburgh. (85.) These troops being wanted by Gen. Amherst for other service, he requested the Governor to make a requisition of provincial troops to take their place. This request met with the usual result. Gen. Monckton in a letter to Governor Hamilton, from Fort Pitt, September 26th, 1760, expressed his sorrow to find that there was a likelihood of the requisition meeting with so much difficulty, and again represented the necessity of keeping up a body, of at least 400 of the Penna. Troops, to assist in garrisoning the forts in that department for the ensuing winter. (86.)

This matter was laid before the Council but the House being then on the point of dissolution, declined to agree to this measure at once, and deferred its consideration to the next Assembly. (87.) On the 17th of October, the Assembly's Answer to the Governor's message was delivered. The reason which they gave for acceding to this request was that since the reduction of Canada and the withdrawal of the French home, there remained nothing for the regular troops in the pay of the "Nation" to do but garrison these posts, from which circumstances they concluded that it was not necessary to engage additional men. (88.)

The Assembly thus not doing anything, Gen. Monckton appealed to Gen. Amherst, the Commander-in-Chief, who addressed the Governor, Feb. 27th, 1761, saying that as it was indispensably necessary that Vaughan's regiment should be removed from their present quarters to Philadelphia, it was requisite to send in their stead for the security and protection of the country, to the several forts and posts within the communication to Pittsburgh, a sufficient number of men properly officered. He requested that 300, so officered, should be raised by the Assembly for that purpose. (89.) The Governor laid the matter before the Assembly. On March the 13th, 1761, the bill being passed, was handed to the Governor, who concurred. (90.)

Gen. Monckton had left Pittsburgh, Monday, the 27th of October, 1760. (91) He, however, had charge of this department for some time thereafter. Amherst, under date of 22d of March, 1761, acquainted the Governor that Gen. Monckton would set out from New York on the day following, on his way to Philadelphia, in order to station the 300 men voted by the Assembly, and to put Vaughan's regiment in motion. (92.)

Little of interest occurred here from this time until Pontiac's war, in 1763. Treaties were held, as we have seen, from time to time with the Indians. Gen. Monckton had held a conference of great moment at the camp on the 12th of August, 1760. Many representatives were present. The tribes were well treated. A great store or trading-house, was set up by the Governor, at Pittsburgh, and one at Shamokin (Sunbury) where the Indians were furnished with all sorts of goods, at a "cheap rate." (93.)

Through almost the entire year of 1762–until late in the fall of that year–there was nothing to indicate anything but a lasting friendship from the Indians about the region of the Ohio. Beaver and Shingas, had sent word by Frederic Post, whose message was delivered to the Governor, Feb. 11th, 1762, that it was their desire to cultivate the friendship of their brethren, the English. (94.) Later in the year, Beaver, and the other Indians with him, entered into solemn engagement to deliver up all the whites whom they held as prisoners, at Fort Pitt. Col. Burd and Josiah Davenport were commissioned to receive them (95.)

The preliminaries of a treaty of peace between France and Great Britain, (as well as other powers), were interchanged on the 3d of November, 1762, and the definite treaty was signed on the 10th of February, 1763. Under this, the whole of the territory between the Allegheny and the Mississippi, together with Canada, passed from the French to the English. In the meantime the greatest Indian uprising in history was being planned by one of the most remarkable savages of whom there is account. This was Pontiac, Chief of the Ottawas. He had been, both from interest and inclination, a firm friend of the French. During the war he had fought on the side of France. It is said that he commanded some of his tribe, when he was yet a young man, at the defeat of Braddock. (96.)

It was a momentous crisis for the Indian race. The English were masters; the French were conquered. This, to one of a mind of the vigor and strength of Pontiac's, meant the loss of all their hunting grounds and the extinguishment of their race. To the Indians were reserved the great privilege of annihilating the English race. His vivid imagination conceived things impossible to be realized. The idea came to him of uniting all the tribes into a confederation of war; to attack all at once the English posts on the frontier from Mackinaw to Fort Pitt, and thus by wresting all their conquests from them, regain for the French as their friends the places from whence they had been displaced, and to restore to the native tribes their rightful heritage.

Toward the close of 1762 he thereupon sent ambassadors to the different nations of savages. These visited the country of the Ohio and its tributaries, passed northward to the region of the Upper Lakes, and the borders of the River Ottawa and far southwards towards the mouth of the Mississippi. Bearing with him the war belt of wampum, broad and long, as the importance of the message demanded, and the tomahawk stained red in token of war, they went from camp to camp, and village to village. Everywhere the message was approved. The blow was to be struck at a certain time in the month of May following, to be indicated by the changes of the moon. The tribes were to rise together, each destroying the English garrison in its neighborhood, and then, with a general rush, the whole were to turn against the settlements of the frontier.

The tribes, then banded together against the English, comprised, with a few unimportant exceptions the whole Algonquin stock, to whom were united the Wyandotts, the Senecas, and several tribes of the lower Mississippi. The Senecas were the only members of the Iroquois confederacy who joined in the league, the rest being kept quiet by the influence of Sir. Wm. Johnson, whose utmost exertions, however, were barely sufficient to allay their irritation. (97.)

Preparations having been thus made all the outposts which were garrisoned by English blood, were assailed about the same time. Within a short period, of the twelve garrisoned forts which were severally attacked, nine fell. Among those taken were Venango, Le Boeuf, Presqu' Isle;–Detroit, Niagara, and Fort Pitt alone remained.

In Pennsylvania at this time, Bedford might be regarded the frontier. Between that point and Fort Pitt about midway was Fort Ligonier on the Loyalhanna. Between Bedford and Ligonier at the western side of the Alleghenies was a stockaded station called Stony Creek. About midway between Ligonier and Fort Pitt, near Bushy Run was Byerly's station. These were all on the line of the Forbes road. From Presqu' Isle (Erie), there was a short over land passage, called a portage, of about fifteen miles to Fort Le Boeuf, on French creek, a branch of the Allegheny; thence the communication was by French creek to Fort Venango (Old Marchault), and thence by the Allegheny to Fort Pitt.

Fort Pitt stood far aloof in the forest, and one might journey eastward full 200 miles, before the English settlements began to thicken. Behind it lay a broken and woody track; then succeeded the great barrier of the Alleghenys traversing the country in successive ridges; and beyond these lay vast woods, extending to the Susquehanna. Eastward of this river, cabins of settlers became more numerous, until in the neighborhood of Lancaster, the country assumed an appearance of prosperity and cultivation. Two roads led from Fort Pitt to the settlements; one of which was cut by Gen. Braddock from Cumberland in 1755; the other, which was the more frequented, passed by Carlisle and Bedford, and was the one made by Gen. Forbes, in 1758. Fort Ligonier and Fort Bedford were nestled among the mountains in the midst of endless forests. Small clearings and log cabins were around each post. From Bedford toward the east, at the distance of nearly 100 miles, was Carlisle, a place resembling Bedford in its general aspect although of greater extent. After leaving Fort Bedford, numerous houses of settlers were scattered here and there among the valleys, on each side of the road from Fort Pitt, so that the number of families beyond the Susquehanna amounted to several hundreds, thinly distributed over a great space. From Carlisle to Harris' Ferry, now Harrisburg, on the Susquehanna, was but a short distance; and from thence, the road led directly into the heart of the settlements. (98.)

At this time Capt. Simeon Ecuyer, a brave Swiss officer, of the same nationality and blood as Bouquet, commanded at Fort Pitt. He early received warnings of danger. On the 4th of May, (1763), he wrote to Col. Bouquet at Philadelphia:

"Major Gladwyn writes to tell me that I am surrounded by rascals. He complains a great deal of the Delaware and Shawanos. It is this canille who stir up the rest to mischief." At length, on the 27th, at about dusk in the evening, a party of Indians was seen descending the banks of the Allegheny, with laden packhorses. They built fires, and encamped on the shore until daybreak, when they all crossed over to the fort, bringing with them a great quantity of valuable furs. These they sold to the traders, demanding, in exchange, bullets, hatchets, and gunpowder; but their conduct was so peculiar as to excite the just suspicion that they came either as spies or with some other insidious design. Hardly were they gone, when tidings came in that Col. Clapham, with several persons, both men and women, had been murdered and scalped near the fort; and it was soon after discovered that the inhabitants of an Indian town, a few miles up the Allegheny, had totally abandoned their cabins, as if bent on some plan of mischief. On the next day, two soldiers were shot within a mile of the fort. An express was hastily sent to Venango, to warn the little garrison of danger; but he returned almost immediately, having been twice fired at, and severely wounded. (99.) A trader named Calhoun now came in from an Indian village of Tuscaroras, with intelligence of a yet more startling kind. At eleven o'clock on the night of the 27th, a chief named Shingas, with several of the principal warriors in the place had come to Calhoun's cabin, and earnestly begged him to depart, declaring that they did not wish to see him killed before their eyes. The Ottawas and Ojibwas, they said, had taken up the hatchet, and captured Detroit, Sandusky and all the forts of the interior. The Delawares and Shawanese of the Ohio were following their example, and were murdering all the traders among them. Calhoun ad the thirteen men in his employ lost no time in taking their departure. The Indians forced them to leave their guns behind, promising them that they would give them three warriors to guide them in safety to Fort Pitt; but the whole proved a piece of characteristic dissimulation and treachery. The three led them into an ambuscade at the mouth of Beaver creek. A volley of balls showered upon them; eleven were killed on the spot, and Calhoun and two others alone made their escape. "I see," writes Ecuyer to his Colonel, "that the affair is general. I tremble for our out-posts. I believe, from what I hear, that I am surrounded by Indians. I neglect nothing to give them a good reception; and I expect to be attacked tomorrow morning. Please God I may be. I am passably well prepared. Every body is at work, and I do not sleep; but I tremble lest my messengers should be cut off."

At Fort Pitt every preparation was made for an attack. The houses and cabins outside the rampart were leveled to the ground, and every morning, at an hour before dawn, the drum beat, and the troops were ordered to their alarm posts. The garrison consisted of 330 soldiers, traders and backwoodsmen; and there were also in the fort about 100 women, and a still greater number of children, most of them belonging to the families of settlers who were preparing to build their cabins in the neighborhood. "We are so crowded in the fort," writes Ecuyer to Col. Bouquet, "that I fear disease; for, in spite of every care, I cannot keep the place as clean as I should like. Besides, the small-pox is among us; and I have therefore caused a hospital to be built under the drawbridge, out of range of musket shot. * * * * I am determined to hold my post, spare my men, and never expose them without necessity. This, I think, is what you require of me."

The desultory outrages with which the war began, and which only served to put the garrison on their guard, far from abating, continued for many successive days, and kept the garrison in a state of restless alarm. It was dangerous to venture outside the walls, and a few who attempted it were shot and scalped by lurking Indians. "They have the impudence," writes an officer, "to fire all night at our sentinels;" nor were these attacks confined to the night, for even during the day no man willingly exposed his head above the rampart. The surrounding woods were known to be full of prowling Indians, whose number seemed daily increasing, though as yet they had made no attempt at a general attack. At length, on the afternoon of the 22nd of June, a party appeared at the farthest extremity of the cleared lands behind the fort, driving off the horses which were grazing then, and killing the cattle. No sooner was this accomplished than a general fire was opened upon the fort from every side at once, though at so great a distance that only two men were killed. The garrison replied by a discharge of howitzers, the shells of which, bursting in the midst of the Indians, greatly amazed and disconcerted them. As it grew dark, their fire slackened, though, throughout the night, the flash of guns was seen at frequent intervals, followed by the whooping of the invisible assailants.

At nine o'clock on the following morning, several Indians approached the fort with the utmost confidence, and took their stand at the outer edge of the ditch, where one of them, a Delaware, named the Turtle's Heart, addressed the garrison as follows:

"My brothers, we that stand here are your friends; but we have bad news to tell you. Six great nations of Indians have taken up the hatchet, and cut off all the English garrisons, excepting yours. They are now on their way to destroy you also.

"My Brothers, we are your friends, and we wish to save your lives. What we desire you to do is this: You must leave this fort, with all your women and children, and go down to the English settlements, where you will be safe. There are many bad Indians already here; but we will protect you from them. You must go at once, because if you wait till the six great nations arrive here, you will all be killed, and we can do nothing to protect you."

To this proposal, by which the Indians hoped to gain a safe and easy possession of the fort, Captain Ecuyer made the following reply. The vein of humor perceptible in it may serve to indicate that he was under no great apprehension for the safely of his garrison:

"My Brothers, we are very grateful for your kindness, though we are convinced that you must be mistaken in what you have told us about the forts being captured. As for ourselves we have plenty of provisions, and are able to keep the fort against all the nations of Indians that may dare to attack it. We are very well off in this place, and we mean to stay here.

"My Brothers, as you have shown yourselves such true friends, we feel bound in gratitude to inform you that an army of 6000 English will shortly arrive here, and that another army of 3000 is gone up the lakes, to punish the Ottawas and Ojibwas,. A third has gone to the frontiers of Virginia, where they will be joined by your enemies, the Cherokees and Catawbas, who are coming here to destroy you. Therefore take pity on your women and children and get out of the way as soon as possible. We have told you this in confidence, out of our great solicitude lest any of you should be hurt; and we hope that you will not tell any of the other Indians, lest they escape from our vengeance. (100.)"

This politic invention of the three armies had an excellent effect, and so startled the Indians, that, on the next day most of them withdrew from the neighborhood, and went to meet a great body of warriors, who were advancing from the westward to attack the fort.

At Fort Pitt, every preparation was made to repel the attack which was hourly expected. A part of the rampart, undermined by the spring floods, had fallen into the ditch; but, by dint of great labor, this injury was repaired. A line of palisades was erected along the ramparts; the barracks were made shot-proof, to protect the women and children; and as the interior buildings were all of wood, a rude fire engine was constructed, to extinguish any flames which might be kindled by the burning arrows of the Indians. Several weeks, however, elapsed without any determined attack from the enemy, who were engaged in their bloody work among the settlements and smaller posts. From the beginning of July until towards its close, nothing occurred except a series of petty and futile attacks, by which the Indians abundantly exhibited their malicious intentions, without doing harm to the garrison. During the whole of this time, the communication with the settlements was completely cut off, so that no letters were written from the fort, or, at all events, none reached their destination; and we are therefore left to depend upon a few meager official reports, as our only sources of information.

On the 26th of July, a small party of Indians were seen approaching the gate, displaying a flag, which one of them had some time before received as a present from the English commander. On the strength of this token, they were admitted, and proved to be chiefs of distinction; among whom were Shingas, Turtle's heart, and others, who had hitherto maintained an appearance of friendship. Being admitted to a council, one of the addressed Captain Ecuyer and his officers to the following effect:

"Brothers, what we are about to say comes from our hearts and not from our lips.

"Brothers, we wish to hold fast the chain of friendship–that ancient chain which our forefathers held with their brethren the English. You have let your end of the chain fall to the ground, but ours is still fast within our hands. Why do you complain that our young men have fired at your soldiers, and killed your cattle and your horses? You yourselves are the cause of this. You marched your armies into our country, and built forts here, though we told you, again and again, that we wished you to remove. My Brothers, this land is our and not yours.

"'Grandfathers the Delawares, by this belt we inform you that in a short time we intend to pass, in a very great body through your country, on our way to strike the English at the forks of the Ohio. Grandfathers, you know us to be a headstrong people. We are determined, to stop at nothing; and as we expect to be very hungry, we will seize and eat everything that comes in our way.'

"Brothers, you have heard the words of the Ottawas. If you leave this place immediately, and go home to your wives and children, no harm will come of it; but if you stay, you must blame yourselves alone for what may happen. Therefore we desire you to remove."

To the wholly unreasonable statement of wrongs contained in this speech, Captain Ecuyer replied, by urging the shallow pretense that the forts were built for the purpose of supplying the Indians with clothes and ammunition. He then absolutely refused to leave the place. "I have," he said, "warriors, provisions, and ammunition, to defend it three years against all the Indians in the woods; and we shall never abandon it as long as a white man lives in America. I despise the Ottawas, and am very much surprised at our brothers the Delaware, for proposing to us to leave this place and go home. This is our home. You have attacked us without reason or provocation; you have murdered and plundered our warriors and traders; you have taken our horses and cattle; and at the same time you tell us that your hearts are good towards your brethren, the English. How can I have faith in you? Therefore, now, Brothers, I will advise you to go home to your towns, and take care of your wives and children. Moreover, I tell you that if any of your appear again about this fort, I will throw bombshells, which will burst and blow you to atoms, and fire cannon among you, loaded with a whole bag full of bullets. Therefore take care, for I don't want to hurt you."

The chiefs departed, much displeased with their reception. Though nobody in his senses could blame the course pursued by Captain Ecuyer, and though the building of forts in the Indian country could not be charged as a crime, except by the most over-strained casuistry, yet we cannot refrain from sympathizing with the intolerable hardship to which the progress of civilization subjected the unfortunate tenants of the wilderness, and which goes far to extenuate the perfidy and cruelty that marked their conduct throughout the whole course of the war.

Disappointed of gaining a bloodless possession of the fort, the Indians, now, for the first time, began a general attack. On the night succeeding the conference, they approached in great numbers, under cover of the darkness, and completely surrounded it; many of them crawling under the banks of the two rivers, and, with incredible perseverance, digging, with their knives, holes in which they were completely sheltered from the fire of the fort. On one side, the whole bank was lined with these burrows, from each of which a bullet or an arrow was shot out whenever a soldier chanced to expose his head. At daybreak, a general fire was opened from every side, and continued with intermission until night, and through several succeeding days. No great harm was done, however. The soldiers lay close behind their parapet of logs, watching the movements of their subtle enemies, and paying back their shot with interest. The red uniforms of the Royal Americans mingled with the gray homespun of the border riflemen, or the fringed hunting-frocks of the old Indian fighters, wary and adroit as the red-skinned warriors themselves. They liked the sport, and were eager to sally from behind their defenses, and bring their assailants to close quarters; but Ecuyer was too wise to consent. He was among them, and as well pleased as they, directing, encouraging, and applauding them in his broken English. An arrow flew over the rampart and wounded him in the leg; but, it seems, with no other result than to extort a passing execration. The Indians shot fire arrows, too, from their burrows, but not one of them took effect. The yelling at times was terrific, and the women and children in the crowded barracks clung to each other in terror; but there was more noise than execution, and the assailants suffered more than the assailed. Three or four days after, Ecuyer wrote to his colonel, "They were all well under cover, and so were we. They did us no harm; nobody killed, seven wounded, and I myself slightly. Their attack lasted five days and five nights. We are certain of having killed and wounded 20 of them, without reckoning those we could not see. I left nobody fire till he had marked his man; and not an Indian could show his nose without being pricked with a bullet, for I have some good shots here. * * * Our men are doing admirably, regular and the rest. All that they ask is to go out and fight. I am fortunate to have the honor of commanding such brave men. I only wish the Indians had ventured an assault. They would have remembered it to the thousandth generation! * * * I forgot to tell you that they threw fire-arrows to burn our works, but they could not reach the buildings, nor even the rampart. Only two arrows came into the fort, one of which had the insolence to make free with my left leg."

This letter was written on the 2d of August. On the day before the Indians had all decamped. An event, described elsewhere had put (101) an end to the attacks, and relieved the tired garrison of their presence. Upon Col. Bouquet's approach to the relief of the post, the Indians gathered from all directions to meet him, and on the 5th and 6th of August was fought the decisive battle at Bushy Run.

The Indians being thus foiled in their attempt on Fort Pitt dispersed. Col. Bouquet not having sufficient force to pursue them beyond the Ohio, was compelled to delay further action that year. His troops were therefore dispersed and stationed along the line of posts for the coming winter, and provisions were laid in for their support. The next spring preparations were early begun for the prosecution of his projected campaign, but it was not until August, 1764, that the new forces assembled at Carlisle, and not until September 17th, that they arrived at Fort Pitt.

In this summer of 1764, was erected the redoubt, still standing, now "the sole existing monument of British dominion," at this point. A tablet was inserted in the wall, with the words: "A. D. 1764, Coll. Bouquet." The structure stands near the point, the "Forks of the Ohio," between Penn Avenue and Duquesne Way.

The Old Block House–more correctly Redoubt–was built by Col. Bouquet in 1764, although it is probable that its construction was begun in the fall of 1763 after Bouquet had relieved Fort Pitt.

It is situated about 300 yards from the Point, on what is now known as Fourth Street, and midway between the junction of the Monongahela and Allegheny Rivers, where they meet and form the Ohio River.

The structure is built of brick, covered with old fashioned clapboards, with a layer of double logs, through which are cut portholes, 36 in number, in two rows, one over the other, for effective work in case of necessity.

The building is 16x15 feet, 22 feet in height; 20 feet high from the floor to the eaves on the roof.

When the Proprietaries, John Penn and John Penn, Jr., determined to sell the land embraced in the Manor of Pittsburgh, Stephen Bayard and Isaac Craig purchased, in January, 1784, all the ground between Fort Pitt and the Allegheny River, supposed to contain about three acres. This is what is now known as the "Schenley property," at the Point.

Col. William A. Herron, the agent of Mrs. Mary E. Schenley, of London, England, the owner of the Block House, presented to the Pittsburgh Chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution, at a regular meeting of the Chapter, April 2d, 1894, a deed for the Block House with a plot of ground 90x100 feet. Miss Denny in behalf of the Daughters received the gift in a beautiful and well chosen address.

Since then the work of restoring the Block House and beautifying the grounds has been completed. A stockade fence has been placed around it for protection and it is now open to visitors. It will serve as a museum for Colonial and Revolutionary Relics.

When the new City Hall was built, the stone tablet which had been inserted in the wall of the Redoubt, was taken out and placed in the wall of the head of the first landing of the stairway of the Hall. On December 15th, 1894, it was taken out of its resting place that it might pass into the custody and possession of the Daughters.

The stone appears to be as sound and perfect as ever. The inscription cut into the tablet consists of the figures "1764" and below them the letters "Coll. Bouquett."

"In this same year, 1764, Col. John Campbell laid out that part of the City of Pittsburgh which lies between Water and Second streets, and between Ferry and Market streets, being four squares. We have never been able to learn (says Mr. Craig) what authority Campbell had to act in this case. But when the Penns afterward authorized the laying out of the town of Pittsburgh, their agent recognized Campbell's act, at least, so far as not to change his plan of lots. We know not precisely at what time of the year Col. Bouquet's redoubt was built, nor when Campbells' lots were laid out; but certainly the last step in perfecting this place as a military post and the first step in building up a town here were taken in the same year." (102.)

In a notice of a visit made to the place in the summer of 1766, by Rev. Charles Beatty and Rev. Mr. Duffield, it is said that "On Sabbath, 7th of September, Mr. McLagan, the chaplain of the Forty-second regiment, invited Rev. Mr. Beatty to preach to the garrison, which he did; while Rev. Mr. Duffield preached to the people who lived in some kind of a town, without the fort." (103.)

From this time until the regular opening of the land office (1769) trouble was apprehended by reason of settlers occupying territory in various parts of the country, particularly on the Monongahela and the Youghiogheny, in violation of the treaty rights of the Indians. Complaint being made, the Governor of Pennsylvania, and the Governor of Virginia, as well as Gen. Gage, the Commander-in-Chief of the British forces in America, used every reasonable exertion to have the settlers peaceably removed. Various conferences and treaties were held during this period between the agents of these officials and the Indians, at and about Fort Pitt. It was provided that the penalties that were attached to the violation of these laws, or treaty obligations, did not extend to those who had settled on the main communications leading to Fort Pitt, under the permission of the Commander-in-Chief, nor to settlement made by George Croghan, Esq., Deputy Superintendent under Sir William Johnson, upon the Ohio above said fort.

On the 5th day of January, 1769, a warrant issued for the survey of the "Manor of Pittsburgh." On the 27th of March, the survey was completed and returned the 19th of May, 1769. It embraced within its bounds 5,766 acres and allowance of 6% for roads, etc.

In October, 1770, George Washington arrived here on his way to the Kenawha. In his Journal for October 17, he says:

"Dr. Craik and myself, with Capt. Crawford and others, arrived at Fort Pitt, distant from the crossing 43-1/2 measures miles. (The crossings were at Connellsville.) We lodged in what is called the town, distant about 300 yards from the fort, at one Semple's, who keeps a very good house of public entertainment. The houses, which are built of logs, and ranged in streets, are on the Monongahela, and I suppose may be about 20 in number, and inhabited by Indian traders. The fort is built on the point between the rivers but was not so near the "pitch of it" as Fort Duquesne stood. Two of the sides which were on the land side were of brick; and the other stockade. A moat encompassed it. The garrison consisted of two companies of Royal Irish, commanded by Capt. Edmondstone." (104.)

The Indians now manifesting a peaceable disposition on the frontier the government was induced to abandon the fort. Accordingly in October, 1772, orders were received by Major Charles Edmondstone from Gen. Gage, the Commander-in-Chief of the British forces, to abandon Fort Pitt. In carrying out this order Major Edmondstone sold the pickets, stones, bricks, timber and iron, in the walls and buildings of the Fort and redoubts, for the sum of £50, New York currency. Fort Pitt was then abandoned, although the fort buildings were not torn down. A corporal and three men were left, to take care of the boats and batteaux intended to keep up the communication with the Illinois country.

This determination created a fear among the inhabitants that they would be exposed to unusual danger by the withdrawal of the garrison, and they petitioned the Governor to prevail if possible with Gen. Gage to have the garrison continued, or to have the fort occupied by soldiers of the province.

To Governor Penn, the General replied Nov. 2d, 1772, as follows: (105.)

"I have received your letter of the 27th ultimo., by Mr. St. Clair, tho' I apprehend too late for me to send any Counter-order to Fort Pitt, for by my letters from thence of the beginning of last month, the garrison only awaited the arrival of Carriages to move away. I am of opinion, however, that the Troops abandoning the Fort, can be of very little consequence to the Public, tho' the Fort might be partially useful. It is no Asylum to Settlers at any Distance from it, nor can it cover or protect the Frontiers, tho' people who are near it, might, upon Intelligence of an Enemy's Approach, take refuge therein. All this was fully evinced in the last Indian War, and I know of no use of forts of the kind, but that of being Military Deposits.

"It is natural for the people near Fort Pitt, to solicit the continuance of the Garrison, as well for their personal security, as obtaining many other advantages; but no government can undertake to erect Forts for the advantage of Forty or Fifty People; every Body of people of the same numbers would think themselves entitled to the same Favor, and there would be no end to Forts. The People have settled gradually from the Sea into the Interior Country, without the aid of Fortresses, and it's to be hoped they will be able to proceed in the way they began, without meeting more obstructions now than they did formerly.

"The List of Ordnance and Stores enclosed in your Letter, which you inform me were lent by the Province of Pennsylvania in 1758, to the late Brigadier General Forbes, shall be examined into, and orders given to return the same to such Person as you shall appoint to receive them."

Fort Pitt upon its abandonment as a military post by the British, was partly but not altogether destroyed. The proprietary government for some time kept a few men here, but only for the purpose of protecting its property. During 1773, a citizen of Pittsburgh, Edward Ward, took possession of what was left and occupied the same until it was taken possession of by Capt. John Connolly, in 1774, with the Virginia militia.

The year 1774 was a time of excitement and movement here. In that year Lord Dunmore passed through this place on his way down the Ohio, to cooperate with Gen. Lewis, of Virginia in an attack upon the Ohio Indians. About the same time the controversy between Pennsylvania and Virginia, about their boundary line, which commenced as early as 1752, seemed to have come to maturity and was on the very verge of gliding into a civil war.

Early in 1774, Dr. John Connolly, who had been commissioned "Captain Commandant of the Militia of Pittsburgh and its Dependencies" by Lord Dunmore, came here from Virginia with authority from that nobleman; took possession of the fort, called at Fort Dunmore; and on the first day of the year issued his proclamation calling the militia together on the 25th of January (1774), at which time he should "communicate matters for the promotion of public utility." (106.)

Col. Mackay informs Gov. Penn, April 4th, 1774, that Connolly was then in actual possession of the fort, with a body guard of militia, invested with both civil and military power, to put the Virginia laws in force in those parts. To induce the people to join and uphold him, very specious means were used by the agents of Dunmore; some were promoted to civil or military employments, and others were encouraged with promises of grants of lands on easy terms.

It was contemplated by the friends and adherents of the Penns, about July, 1774, to abandon Pittsburgh and to erect a small stockade somewhere lower down the Forbes road, supposedly near Turtle creek, to secure their cattle and effects. (107.)

The stockade built or refurnished by Connolly appears to have been used by him as a kind of jail or lockup in which he put persons who did not agree with him politically, and as a guardhouse in which to confine his drunken or insubordinate militia. It is spoken of in the correspondence preserved in the fourth volume of the State Archives, in various places as such a structure specially used for the purposes mentioned. (108.)

The Pennsylvanians did not under the circumstances have much veneration for Fort Dunmore, and St. Clair, in anticipation of the withdrawal of Connolly and his men from Pittsburgh, inquiries of Gov. Penn, May 25, 1775,–"If the fort should be evacuated next month, Pray, Sir, would it be proper to endeavor to get possession of it, or to raze it?–that (however) may be possibly be done by themselves." (109.)

These troublous times, which we cannot dwell upon here, continued until the beginning of 1775. But the power of Lord Dunmore and his agent, Connolly, was, however, fast drawing to a close. On the 8th of June, the former abandoned his palace in Williamsburg, and took refuge on board the Fowey man-of-war, where soon after he was joined by Connolly, who was then busily engaged in planning an attack upon the western frontier. (110.)

The continued collisions and disorder at Pittsburgh could not fail to attract the attention of all the patriotic citizens of the two States, and on the 25th of July, 1775, the Delegates in Congress, including among others, Thomas Jefferson, Patrick Henry, and Benjamin Franklin, united in a circular, urging the people in the disputed region, to mutual forbearance. In that circular was the following language: "We recommend it to you, that all bodies of armed men, kept up by either party, be dismissed; and that all those on either side, who are in confinement, or on bail, for taking part in the contest be discharged."

There were no armed men maintained by the Pennsylvanians; so that the expression about "either party," was probably only used to avoid the appearance of invidiousness; and Connolly and his men had taken effectual measures for the release of Virginians from confinement.

On the 7th of August, the following resolution was adopted by the Virginia Provincial Convention, which had assembled at Williamsburg, on the first of the month:

"Resolved,

That Captain John Neville be directed to march with his company of 100 men, and take possession of Fort Pitt, and that said company be in the pay of the Colony from the time of their march."

The arrival of Captain Neville at Fort Pitt (111) seems to have been entirely unexpected to the Pennsylvanians, and to have created considerable excitement. Commissioners appointed by Congress, were then there to hold a treaty with the Indians and St. Clair in a letter to John Penn, dated 15th of September, has the following remarks: "The treaty is not yet opened, as the Indians are not come in; but there are accounts of their being on the way, and well disposed. We have, however, been surprised by a manoeuver of the people of Virginia, that may have a tendency to alter their favorable disposition.

"About 100 armed men marched from Winchester, and took possession of the fort on the 11th instant, which has so much disturbed the Delegates from the Congress, that they have thoughts of moving some place else to hold the treaty.

This step has already, as might be expected, served to exasperate the dispute between the inhabitants of the country, and entirely destroyed the prospect of a cessation of our grievances, from the salutary and conciliating advice of the Delegates in their circular letter."

There is perhaps, some difficulty in reconciling the conduct of the Virginia Convention, in ordering Captain Neville to Fort Pitt, with the recommendation of the Virginia and Pennsylvania Delegates in Congress, that 'all bodies of armed men in pay, of either party,' should be discharged. No doubt, however, this only referred to the bodies of armed men, kept up by the Virginians or Pennsylvanians in the disputed region. St. Clair seems always to have been very watchful of the interests of Pennsylvania during the controversy; and no doubt, the surprise expressed by him was unaffected; and yet there were strong reasons why Fort Pitt should be promptly occupied by troops in the confidence of the Whigs of the Revolution. The war for independence had commenced by the actions at Lexington and Bunker Hill; and Connolly, a bold, able and enterprising men, was busy arranging some scheme of operations, in which Fort Pitt would be an important and controlling position. It would seem, therefore, to have been nothing more than an act of ordinary prudence and foresight to send here some officers, in whose firmness, fidelity and discretion, implicit confidence could be placed.

The year 1775 is the year of Lexington and Concord. At the very time when the United Colonies commenced their great struggle against the arbitrary schemes of Great Britain, the inhabitants of this section of country, were not only involved in hostilities with the Indian tribes, but were almost on the very of civil war among themselves. Under such circumstances, it would scarcely be expected that they would be at leisure and disposed to enter into the contest against the mother country, upon a mere abstract question, unaccompanied by any immediate, palpable acts of oppression. Yet we find that on the 16th of May, 1775, only four weeks after the battle of Lexington, meetings were held at this place, and at Hannastown, and resolutions unanimously passed in entire consonance with the feeling of the other portions of the country. The meeting here was composed of Virginians and Pennsylvanians. The resolution adopted on that occasion at Pittsburgh, then styled Augusta County (Virginia), may be found in Craig's History of Pittsburgh, page 128. Those adopted the same day at Hannastown are reproduced in this report, where account is given of that place.

In April, 1776, Col. George Morgan was appointed by Congress, Indian Agent for the Middle Department in the United States, and his headquarters fixed at Pittsburgh. From his journals and letters, we get occasional notices of transactions here. Through his mediation largely the Indian nations were kept from any general uprising.

The winter of 1776-7 was spent in comparative quiet, in Fort Pitt. Maj. Neville was still in command there with his company of 100 men.

Under the instigation of Hamilton, the British Governor and superintendent at Detroit, the Indians were now in small band marauding upon the border settlements. On the 22d of February, 1777, fourteen boat carpenters and sawyers arrived at Fort Pitt from Philadelphia, and were set to work on the Monongahela, fourteen miles above the fort, near a sawmill. They built 30 large batteaux, 40 feet long, nine feet wide, and 32 inches deep. They were intended to transport troops in case it became necessary to invade the Indian country. (112.)

On Sunday, the first day of June, 1777, Brigadier-General Edward Hand of the Continental army arrived at Fort Pitt, and assumed the chief command at Pittsburgh. His garrison was a fixed nature– regular, independents, and militia. Not long after his arrival, Hand resolved upon an expedition against the savages,–seemingly a timely movement, for up to the last of July there had been sent out from Detroit to devastate the western settlements, 15 parties of Indians, consisting of 289 braves, with 30 white officers and rangers. The extreme frontier line needing protection on the north, reached from the Allegheny mountains to Kittanning on the Allegheny river 45 miles above Pittsburgh, thence on the west, down that stream and the Ohio to the mouth of the Great Kanawha. The only posts of importance below Fort Pitt, at this date, were Fort Henry at Wheeling, and Fort Randolph at Point Pleasant; the former was built at the commencement of Lord Dunmore's war in 1774; the latter was erected by Virginia in 1775. Rude stockades and blockhouses were multiplied in the intervening distances and in the most exposed settlements. They were defended by small detachments from the Thirteenth Virginia regiment; also by at least one independent company, (Capt. Samuel Moorhead's Independent Company of Pennsylvania troops), and by squads of militia on short tours of duty. Scouts likewise patrolled the country where danger seemed most imminent.

Expeditions against the Indians were attempted about this time from the Western Department with varying results. In January, 1778, Lieutenant-Colonel George Rogers Clark, left Redstone Old Fort (Brownsville), and succeeded in the reduction of the British posts between the Ohio and the Mississippi rivers–Kaskaskia, St. Phillips, Cahokia and Vincennes.

On the 28th of March, 1778, Alexander McKee, Matthew Elliott and Simon Girty, fled from the vicinity of Fort Pitt to the enemy. These three renegades afterward proved themselves active servants of the British government, bringing untold misery to the frontiers, not only while the Revolution continued, but throughout the Indian war which followed that struggle. Their influence was immediately exerted to awaken the war spirit of the savages. Going directly to the Delawares, they came very near changing the neutrality of that nation to open hostility against The United States–frustrated, however, by the prompt action of Gen. Hand, and of Morgan, who was still Indian Agent at Fort Pitt, and by the timely exertions of the Moravian missionaries upon the Tuscarawas. After leaving the Delaware, these traitors proceeded westward, inflaming the Shawanese and other tribes to a white heat of rapacity against the border settlements. Thence they made their way to Detroit. (113.)

Gen. Hand requesting to be recalled from Pittsburgh in order to join actively in the operations in the army under Washington, he was relieved of the command of the Western Department, and Brigadier-General Lachlan McIntosh, on Washington's nomination, was sent to succeed him. On the 26th of May, he was notified of his appointment.

On the 2d of May, 1778, Congress had resolved to raise two regiments in Virginia and Pennsylvania, to serve for one year unless sooner discharged, for protection of the western frontier, and for operation thereon;–twelve companies in the former and four in the latter State.

For reasons which were apparent to them, Congress determined that an expedition should be immediately undertaken to reduce if practicable, the fort at Detroit, and compel the hostile Indians inhabiting the country contiguous to the route between Pittsburgh and that post, to cease their aggressions.

Before Congress determined to begin active measures against Detroit and the hostile savages, Washington, upon receipt of information concerning Indian ravages upon the western frontier, had ordered the Eighth Pennsylvania regiment, a choice body of men, who had been raised west of the mountains–100 of them having been constantly in Morgan's rifle corps–to prepare to march to Pittsburgh, a detachment having been already sent to that department. At the head of these troops was Colonel Daniel Brodhead. Previous to this, the men of the Thirteenth Virginia remaining at Valley Forge, had been placed under marching orders for the same destination, as they, too , were enlisted in the West. The others, numbering upwards of 100 were already at or near Fort Pitt. The command of this regiment was given temporarily to Col. John Gibson. (114) Brodhead arrived at Pittsburgh on the 10th of September, (1778).

McIntosh had not been long in the West when he discovered that a number of storehouses for provisions, which had been built at public expense, were at great distances apart, difficult of access, and scattered throughout the border counties. At each of these, a number of men was required. These buildings were given up, as the provisions in them intended for the expedition which was projected against Detroit, proved to be spoiled. In place of them, one general storehouse was built by a fatigue party, "in the fork of the Monongahela river," where all loads from over the mountains could be discharged, without crossing any considerable branch of any river. (115.)

On the 17th of September, a treaty was signed between commissioners, appointed at the suggestion of Congress, and representatives of the Delawares. Although the Indians had been invited, none of the Shawanese came, they being now openly hostile to the United States. The Delawares were represented by their three principal chiefs, White Eyes, Captain Pipe, and John Kilbuck, Jr. By its terms, not only were the Delawares made close allies of The United States and "The hatchet put into their hands,"–thus changing, and wisely too, the neutral policy previously acted upon,–but consent was obtained for marching an army across their territory. They stipulated to join the troops of the general government with such a number of their best and most expert warriors as they could spare, consistent with their own safety. A requisition for two captains and 60 braves was afterward made upon the nation by the American commander. (116.)

The territory of the Delawares, as claimed by them at that date, was bounded on the east by French creek, the Allegheny, and the Ohio–as far down the last mentioned stream as Hockhocking, at least; on the west, by the Hockhocking and the Sandusky. They even advanced claims to the whole of the Shawanese country.

Gen. McIntosh then built Fort McIntosh, on the right bank of the Ohio at Beaver, and opened the road to that point. By the 8th of October, 1778, the headquarters of the army were removed from Fort Pitt to the new fort, where the largest body of troops collected west of the Alleghenies during the Revolution was assembled, preparatory to beginning the march against Detroit. This force consisted, besides the continental troops, of militia, mostly from the western counties of Virginia. But the want of the necessary supplies prevented any immediate forward movement.

On the 5th of November the movement of the army westward commenced. The Tuscarawas was reached, a distance of about 70 miles from Fort McIntosh, at the end of 14 days. He expected to meet the hostile Indians here, but none appeared. Being informed that the necessary supplies for the winter had not reached Fort McIntosh, and that very little could be expected, there was now no other alternative but to return as he came, or to build a strong fort upon the Tuscarawas, and leave as many men as provisions would justify, to secure it until the next season. He chose the latter alternative, and built Fort Laurens, the first military post of the government erected upon any portion of the territory now constituting the State of Ohio. Leaving a garrison of 150 men, with scanty supplies, under command of Colonel John Gibson, to finish and protect the work, McIntosh, with the rest of his army, returned, very short of provisions, to Fort McIntosh, where the militia under his command were discharged.

During this winter the Eighth Pennsylvania regiment was assigned to Fort Pitt. The men left in Fort Laurens were a part of the Thirteenth Virginia. The residue, with the independent companies, were divided between Fort McIntosh, Fort Henry, Fort Randolph and Fort Hand; with a few at inferior stations. There was not one of the militia retained under pay at either of these posts.

An April, 1779, McIntosh dispirited and with health impaired, retired from the command of the Western Department. Under his direction of the department, the attention of the savages had, to some extent, been diverted from the border, and the anxiety at Detroit considerably increased. In the management of affairs in the Western Department not immediately connected with aggressive movements beyond the Ohio, McIntosh had exercised good judgment. He had carefully avoided interfering with the troublesome boundary question, although often applied to by both sides; as it was wholly out of his power to remedy the evil. He had reserved cordial relations with the several county lieutenants and had been active and vigilant in protecting the exposed settlements. The erection of Forts McIntosh and Laurens as a precautionary measure was approved by the Commander-in-Chief. (117.)

Congress having directed the appointment of a successor to General McIntosh, Washington, on the 5th of March, (1779), made choice of Major Daniel Brodhead, of the Eighth Pennsylvania regiment, who was then first in rank in the Western Department under Gen. McIntosh.

The Letter Book and the Correspondence of Col. Daniel Brodhead during the time he was in command of the Western Department gives a satisfactory account of the affairs about this point, and from this authority without specially indicating the references, the following extracts are taken. The letters date from April, 1779, to the latter part of 1780. (118.)

On April 15th, (1779), he represents to the Hon. Timothy Pickering the necessity for clothing for his regiment, the supply being inadequate, and that a number of recruits and drafts were expected to join in the course of a few weeks; and on the 17th , to Colonel Thomas Smyth, Deputy Quarter-Master General, that "the troops here are in great distress in want of provisions and I am unable to strike a single stroke until a supply arrives. I am informed that a considerable quantity is arrived at Bedford, and I must entreat you if possible to sent it on immediately."

To Gen. Washington, May 22d, 1779, he says, "I am very happy, in having permission to establish the posts at Kittanning and Venango, and am convinced they will answer the grand purposes mentioned in your letter. The greatest difficulty will be to procure salt provisions to subsist the garrisons at the different advanced posts; but I have taken every promising stop to obtain them. * * * You can scarcely conceive how difficult it has been for some time past to procure meat for the troops at this post. I think we have been without the article upwards of 20 days, since General McIntosh went down the country; and yet I have the satisfaction to inform you that the troops have not at any time complained.

To Col. George Morgan May 22d, 1779: he writes that he had written to Col. Steel to purchase a net, such as is used in the Delaware, and he believed it would answer a valuable purpose here.

June 27th, (1779), he complains in a letter to Timothy Pickering that "The inhabitants of this place are continually encroaching on what I conceive to be the rights of the garrison and which was always considered as such when the fort was occupied by the King of Britain's troops. They have now the assurance to erect their fences within a few yards of the bastion. I have mentioned the impropriety of their conduct but without effect, and I am not acquainted with any regulations of Congress respecting it, but hope they will, if they have not already done it, declare their pleasure with regard to the extent of clear ground to be reserved at this and other posts for parades, etc., which in my opinion ought at least to be the range of a musket, and I entreat you will be so obliging as to mention it to some of the members of that honorable body. Gen. Armstrong is well acquainted at this place, and will be a very proper person to inform Congress satisfactorily to the extent of ground occupied by the British troops. The blockhouses likewise which are part of the strength of the place are occupied and claimed by private persons to the injury of the service."

To Col. Stephen Bayard, July 9th, 1779, he conveys the information that:

"Whilst I am writing, I am tormented by at least a dozen drunken Indians, and I shall be obliged to remove my quarters from hence on account of a cursed villainous set of inhabitants, who, in spite of every exertion continue to rob the soldiers, or cheat them and the Indians out of every thing they are possessed of."

In a circular letter addressed to the lieutenants of the counties within his department, from headquarters July 17th, 1779, he informs them that:

"His Excellency the Commander-in-Chief, has at length given me a little latitude, and I am determined to strike a blow against one of the most hostile nations, that in all probability will effectually secure the tranquility of the frontiers for years to come. But I have not troops sufficient at once to carry on the expedition and to support the different posts which are necessary to be maintained. Therefore beg, you will engage as many volunteers for two or three weeks as you possibly can. They shall be well treated, and if they please, paid and entitled to an equal share of the plunder that may be taken, which I apprehend will be very considerable. Some of the friendly Indians will assist us on this enterprise."