REPORT OF THE COMMISSION TO LOCATE THE SITE OF THE FRONTIER FORTS

OF PENNSYLVANIA.

Volume One.

Clarence M. Busch

State Printer of Pennsylvania, 1896.

Contributed for use in the USGenWeb Archives by Donna Bluemink.

Transcriber's note: Some language, spelling and grammar have been updated for ease of

reading without compromising content.

MANADA FORT.

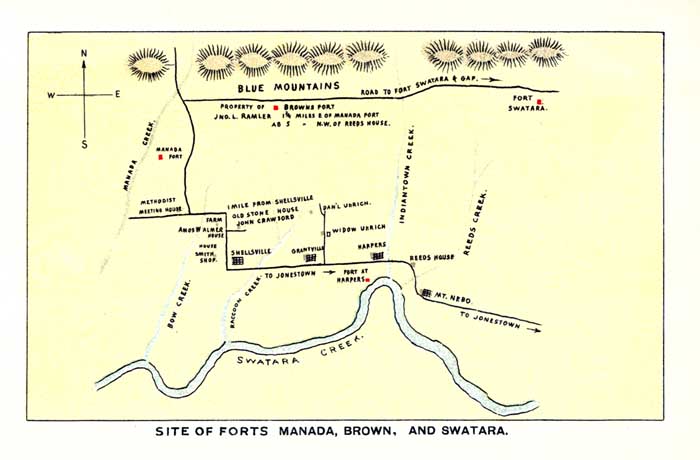

(Site of Forts Manada, Brown, and Swatara.)

The passage through the Blue Mountains, called Manada Gap, is distant from Fort Hunter about twelve miles. Because of this fact, and the necessity for guarding such a prominent gateway to the populous district below, the Government occupied said locality as its next station, in accordance with its general plan of defense. In the few descriptions given of this position more or less confusion exists. Fortunately, by extensive personal research, I have been able to solve the problem. To understand it more thoroughly it will be well, first, to glance at such records of the place as exist.

Immediately after the outbreak of the savages along the Susquehanna, during the Fall of 1755, they began to threaten the settlements further east. We accordingly find the instructions issued to Adam Read, under date of January 10th, 1756, of which mention has already been made, to detach 25 men from the Company at his house and send them to Hunter's Mill, so that they might range the mountains between that place and his residence. With the rest of his command, which remained at his house, he, in turn, was likewise to range the mountains towards Fort Hunter. (Penn. Arch., ii, p. 545.) These instructions were soon followed by the notification, January 26th, to Mr. Read, that "Capt. Frederick Smith having been appointed to take post with an Independent Company at the Gap where Swehatara [Swatara] passes the Mountains, and to station a detachment of his Company at Monaday [Manada]," there would no longer be any necessity for him to guard that frontier and that accordingly he was relieved from said duty. (Penn. Arch., ii, p. 551.) In connection with these instructions to Mr. Read, and of the same date, were the orders sent to Capt. Smith, viz:

Sir: - "Having appointed you captain of a company of foot to be paid and supplied, I think it necessary to give you the following orders and instructions, according to the following establishment, viz: for your better government in the execution of the trust reposed in you. * * * * You are to leave at Swehatara [Swatara] a part of your company, sufficient to maintain that post under one of your officers, and with the remainder of your company you are to proceed to the gap where the river Monaday [Manada] passes the mountains, and either take possession and strengthen the stuccado [stockade] already erected there, or erect a new one as you shall judge best, and then you are to return to the fort at Swehatara [Swatara], which you are to make your headquarters, leaving 20 men under the command of a commissioned officer at the fort at Monaday [Manada], and relieving them from time to time, in part or in whole as you shall think proper.

You are to communicate these instructions to your officers, that are stationed at the fort at Monaday [Manada], and if you judge it necessary you may give them copies for their better government.

As your are unacquainted with the situation of the country, on the northern frontier of the county of Lancaster (now Lebanon), where you are to take post, I have directed James Gelbreth [Galbraith], Esq., to furnish you with all the information in his power, and to afford you his advice and assistance, not only in the choice of ground proper to erect the forts upon, but as to any other matters that may relate to the service you are upon, and you will apply to him for such assistance from time to time as you stand in need of it.

You are to receive of Capt. Read and Capt. Hedericks, such arms, accouterments, blankets and stores, as belong to the Province of which you are to return an exact account to me, and take care of such as shall remain in your hands, and having ordered Capt. Thomas McKee to raise a company of 30 men, and to take post and scour the country between Susquehanna and Monaday [Manada], you are upon his application to supply him with such of the s'd [said] arms, accouterments, tools, blankets and stores as you can spare from your own company, taking his receipt for the same, and inform me of what you supply him with." (Penn. Arch., ii, p. 552-553.)

In conjunction with these orders to Capt. Smith, the Governor wrote as follows to James Galbraith, the Commissary: "I have ordered Capt. Smith, with a company from Chester County, to take post at the Gap at Swehatara [Swatara], and to station a detachment of his men at Monaday [Manada], either in the stockades already built there, or to erect such others as he may judge best; but as he is a stranger to that part of the country, I must desire you will assist him with your advice, not only as to the most advantageous situations for the forts, in case it should be resolved to erect new one, but in anything else that the service may require, and let me know from time to time what is done in that quarter." (Penn. Arch., ii, p. 554.)

These records indicate that a stockade had already been erected, or commenced, prior to 1756. Like Fort Hunter it is probable that it was built by the settlers, during the latter part of 1755, for mutual protection, and later, in January, 1756, occupied by the soldiers. Whilst the instructions of the Governor give license to erect a new fort, if deemed advisable, yet it is most likely Capt. Smith, the commanding officer, accepted the already completed work of the settlers, placed according to their good judgment. Amongst the comparatively few papers which give an account of Manada Fort there is nothing stated to the contrary, and my personal investigations tend to prove the same fact.

On July 11th, 1756, Col. Conrad Weiser gives Gov. Morris a statement of his disposition of the troops, wherein "nine men are to stay constantly in Manity [Manada] Fort, and six men to range eastward from Manity [Manada] towards Swataro [Swatara], and six men to range westward towards Susquehanna. Each party so far that they may reach their fort again before night." (Penn. Arch., ii, p. 696.)

Notwithstanding these apparently active preparations and the faithful scouting doubtless done by the soldiers, yet the Indians were not to be thwarted in their murderous work, and, before long, some of their own number were to fall victims to the unfailing vigilance of the savage, owing, it must be admitted, to a temporary relaxation of their own watchfulness. In a letter of August 7th, 1756, to Edward Shippen this interesting and unfortunate event is related by Adam Read, as follows:

Sir: "Yesterday, Jacob Elles, a soldier of Capt. Smith's at Brown's fort, a liver [little] before 2-1/2 miles over the first mountain, just within the gap at s'd forth [said fort], having some wheat growing at his place, prevailed with his officer for some of the men to help him to cut a little of the same. Accordingly 10 of them went, set guards round and fell to work, about 10 o'clock, they had reaped down and went to the head to begin again, and before they had all well begun, three Indians crept to the fence just at their back and all three at one penal [?] of the fence fired upon them, killed their corporal dead and another that was standing with his gun in one hand and a bottle in the other was wounded, his left arm is broken in two places so that his gun fell, he being a little more down the field, the field being about 15 or 16 poll [pole - unit of measure] in length, them that reaped had their arms about half way down at a large tree. As soon as the Indians found they did not load their guns but leaped over the fence into the middle of them and one of them left his gun behind him without the fence, they all ran through one another, the Indians making a terrible holo [holler], and looked more like the devil than an Indian. The soldiers fled to their arms and as three of them stood behind the tree with their arms the Indian that came in wanting his gun, came within a few yards of them and took up the wounded soldier's gun and would have killed another had not one that pursued him fired at him, so that he dropped the gun. The Indian fled, and in going off, two soldiers stood about a rod apart, an Indian ran through between them, they both fired at him, yet he went off clear. When they were over the fence a soldier fired at one of them upon which he stooped a little and so went all three off. A little after they left the field they fired one gun and gave a hollo [holler]. The soldier hid the one that was killed, went home to the fort, found James Brown that lives in the fort, one of the soldiers, missing. The lieutenant went out with more men and brought in the dead man but still Brown was missing. I heard shooting that night. I went up next morning with some hands, Capt. Smith had sent up more men from the other fort, went out next morning and against I got there word had come in from them [that] they had found James Brown killed and scalped. I went over with them to bring him home. He was killed with the last shot about 20 pole from the field of battle, his gun, his shoes and jacket carried off. The soldiers that found him told me that they tracked the three Indians to the second mountain and they found one of the Indian's guns a little from Browns corpse, broke [it] into pieces as it had been good for little. They showed me where the Indians fired through the fence and it was a full eleven yards to where the man lay dead; the rising ground above the field was clear of standing timber and the grubes low, so that they kept a bad lookout. The above account you may depend upon me. We have almost lost all hope of anything but to move off and lose our crops [that] we have reaped with so much difficulty." (Penn. Arch., ii, p. 738.)

On the same subject and about the same time Commissary James Galgraith wrote, August 10, from Derry, to Governor Hamilton, as follows:

"Honored Sir, There is nothing here almost everyday but murder committed by the Indians in some part or other; about five miles above me, at Monaday [Manada] Gap, there were two of the Province soldiers killed, one wounded; there was but three Indians, and they came in amongst ten of our men and committed murder, and went off safe; the name or sight of an Indian makes almost all mankind in these parts to tremble, their barbarity is so cruel where they are masters, for by all appearances the Devil commits, God permits, and the French pays, and by this the back parts by all appearance will be laid west [waste] by flight, with what is gone and agoing., more especially Cumberberland County." (Penn. Arch., ii, p. 740.)

How many more unfortunates in this neighborhood fell victims to the merciless tomahawk, which was fast laying waste all the frontier settlements, as Mr. Galbraith said, is not stated, but in October, 1756, Adam Read sends another letter to Mr. Shippen, &ca., pleading for assistance, which was duly laid before the Provincial Council and appears on its minutes as follows:

"Friends and Fellow Subjects:

I send you, in a few lines, the melancholy condition of the frontiers of this county; last Tuesday the 12th of this instant, ten Indians came on Noah Frederick plowing in his field, killed and scalped him and carried away three of his children that were with him, the eldest but nine years old, plundered his house, and carried away everything that suited their purpose, such as clothes, bread, butter, a saddle and good rifle gun &ca, it being but two short miles from Capt. Smith's Fort, at Swatawro [Swatara] Gap, and a little better than two from my house.

Last Saturday evening an Indian came to the house of Philip Robeson, carrying a green bush before him, said Robeson's son being on the corner of his fort watching others that were dressing flesh [with] him. The Indian, perceiving that he was observed fled. The watchman fired but missed him; this being three-quarters of a mile from Manady [Manada] Fort; and yesterday morning, two miles from Smith's Fort, at Swatawro [Swatara], in Bethel Township, as Jacob Fornwal was going from the house of Jacob Meyler to his own, was fired upon by two Indians and wounded, but escaped with his life, and a little after, in the said township, as Frederick Henley and Peter Stample were carrying away their goods in wagons, were met by a parcel of Indians and all killed, five lying dead in one place and one man at a little distance, but what more is done is not come to my hand as yet, but that the Indians were continuing their murders. The frontiers is employed in nothing but carrying off their effects, so that some miles is now waste. We are willing, but not able without help; You are able if you be willing (that is including the lower part of the country), to give us such assistance as will enable us to redeem our waste land; you may depend on it that without assistance we in a few days will be on the wrong side of you, for I am now a frontier, and I fear that the morrow night I will be left some miles. Gentlemen, consider what you will do, and not be long about it, and let not the world say that we die as fools died. Our hands are not tied, but let us exert ourselves and do something for the honor of our country and the preservation of our fellow subjects. I hope you will communicate our grievances to the lower parts of our county, for surely they will send us some help if they understand our grievances. I would have gone down myself, but dare not, my family is in such danger. I expect an answer by the bearer, if possible.

I am, Gentlemen,

Your very humble servant,

ADAM READ.

Before sending this away I have just received information that there are seven killed and five children scalped alive, but not the account of their names."

On reading these accounts the governor was advised to lay them and the other intelligence before the Assembly, and in the strongest terms to press them again for a militia law, as the only thing that would enable the country to exert their strength against these cruel savages. (Col. Rec., vii, p. 303.)

This was immediately done by the Governor but action on the part of the Quaker Assembly was very slow and the terrible work still went on.

Here practically ends the narrative of recorded events in and about Manada Gap, except the interesting journal of Capt. James Patterson, stationed at Fort Hunter, which is dated December, 1757. His duties kept him ranging along the mountains between that place, Manada and Swatara Gaps, and the journal has already been given under the head of Fort Hunter. In addition to this journal is a diary of James Burd whilst on his tour of inspection to the various forts. At 11:00 A.M., on Sunday, February 19, 1758, he left Fort Hunter on his way to Fort Swatara. He says "got to Crawford's, 14 miles from Hunter's, here I stay all night, it rained hard. Had a number of applications from the country for protection, otherwise they would be immediately obliged to fly from their settlements, appointed to meet them to hear their complaints, and proposals on Tuesday at 10:00 A.M., at Fort Swatara; the country is thick settled this march along the Blue Mountains and very fine plantations." Upon his arrival at Fort Swatara he reviewed the garrison, inspected the fort and its stores, and gave orders for a sergeant and twelve men to be always out on the scout towards Crawford's, near Manada Gap. On Tuesday, February 21st, the country people came in according to appointment, when, after hearing their statement, he promised to station an officer and 25 men at Robertson's Mill "situated in the center between the forts, Swatara and Hunter," which gave the people content. (Penn. Arch., iii, p. 352-253.)

After reading over these various records we notice that four places are mentioned where soldiers were stationed and which were used for defense: - Robinson's, Robeson's, or Robertson's Mill (as the writer saw fit to spell the name), Manada Fort, Brown's Fort and Squire Read's house. The misunderstanding with regard to Manada Fort has been caused by the confounding of these names in the effort to produce one or two places only out of what are really four separate and distinct stations.

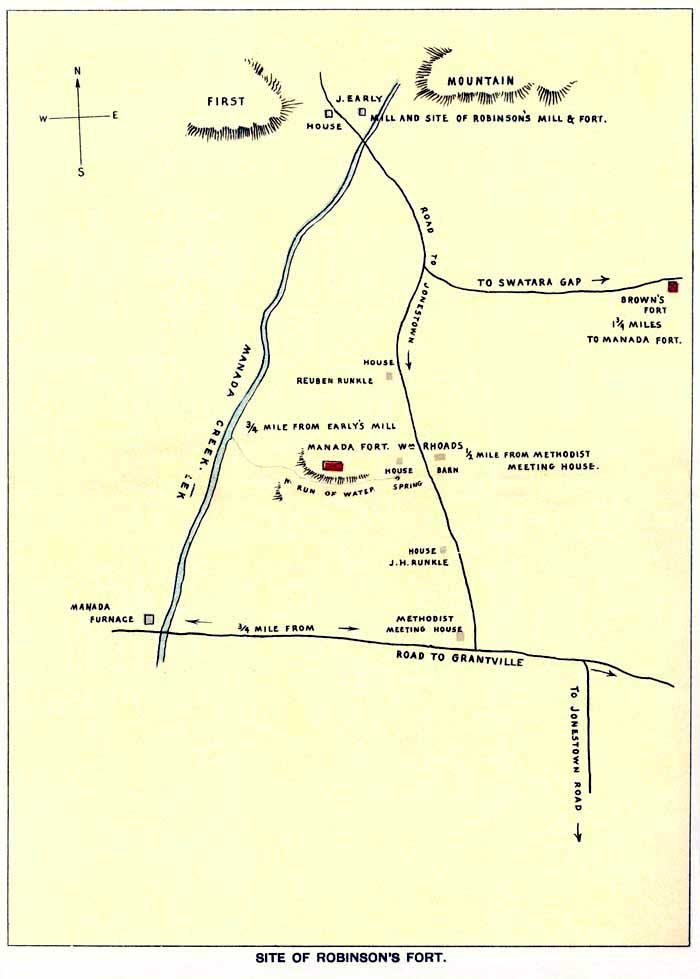

At this point there is back of the First Mountain, or Blue Range proper, a series of other ranges, known as the Second , Third, Fourth, Peter's Mountain, &c. Manada Gap is the narrow passage in the First Mountain where the Manada Creek, formed between it and the Second Mountain, has forced its way through, on its journey towards its larger sister, the Swatara Creek. Right at this entrance stands today the grist mill of Mr. Jacob Early on the site of the old Robinson Mill. Mr. Early showed me at the time of my visit November 22, 1893, an old deed of property dated November 23, 1784, to John and James Pettigrew, for over 350 acres of land of Timothy Green, on part of which the mill now stands. He then explained that his present mill was built in 1891, taking the place of a frame structure erected some 55 years ago, which, in its turn, rested on the foundation of the original mill. This latter was a stone building, and Mr. Early was told by the old inhabitants that it had loop holes in it, larger inside than outside and undoubtedly intended for musketry. It was admirably adapted for defense and, as we have seen, was so used. It was from this building, called "Robeson's Fort," that a lad standing at a corner window, whilst watching some of the men dressing meat, noticed the approach of an Indian who was endeavoring to conceal himself behind a green bush, and who fled when discovered and fired upon. Whilst excellent, however, in itself, as a place of defense, it was too close to the mountain to be conveniently located as a place of refuge and protection for the settlers, who dwellings were generally more distant from the Gap proper. The real Manada Fort, therefore, was built a short distance below the mill, probably by the settlers themselves, in accordance with their own judgment, as already stated. Justice Adam Read, in his appeal to the Provincial Council for assistance, in speaking of the above incident of the lad discovering the Indian, distinctly says that "Robeson's Fort" (the Mill) was three-quarters of a mile from Manada Fort. Diligent search on my part finally resulted in ascertaining the exact and authentic location of the latter fort, which corresponds precisely with the record. My principal information was obtained from Mr. John N. Hampton, an old gentleman 94 years of age, now residing near Grantville, some miles distant, who still remains in perfect possession of all his mental faculties and physical powers. It so happened that Mr. Hampton, when a young man, was engaged in cutting wood at the very spot where the fort had stood, the property then of William Thome. Noticing an unusual quantity of dead timber he inquired of young Mr. Thome the reason and was informed that this was the place where stood the Indian fort. Old Mr. Thome who died 80 years ago an aged man, also stated the same thing. The fact, acquired in this unusual way, became indelibly impressed upon his memory. More recently I have had this location corroborated by Mr. Ziegler, and intelligent elderly gentleman residing near Harper's, Lebanon county, who remembers hearing old people mention it in his youth, and also others. I give a topographical sketch showing more in detail the situation.

As will be seen Robeson's or Robinson's Mill and Fort stood right in the Mountain Gap, beside the Manada creek. Three-quarters of a mile below was Manada Fort, as shown. It stood at what is now the west end of the field on which William Rhoad's house is built, about 350 yards from the same, and about 300 yards distant from Manada creek, beyond it ot the west. The ground is level and somewhat elevated, falling away from the fort to a run of water, immediately below, which originates in a spring near Mr. Rhoad's house and flows west into Manada creek. About one-half mile to the southeast is the Methodist Meeting House, and probably an equal distance to the southwest the Manada Furnace. No trace of the fort remains, nor any knowledge of its appearance, although, from the fact that it was not one of the larger stations, we are justified in presuming that it consisted merely of one block house surrounded by a stockade.

I have previously said that some confusion exists with regard to the number and location of forts in this vicinity, owing principally to the letter written by Mr. Read to Edward Shippen detailing the fight which the soldiers had with the Indians in the Gap and death of James Brown.

Before taking this matter up fully it is well to remember that the most populous part of the district was not close to the mountains, where stood Manada Fort and Robeson's Mill, but down towards the region of the Swatara creek. The first position was necessary as it commanded the passage through the mountains; the other was equally necessary for protection to the inhabitants and as a place of refuge for them. Accordingly, in the early history of savage depredations we read of the farmers organizing into companies which made the house of Adam Read their rallying point, and later of a body of provincial troops stationed likewise at his home and under his command. It might be well here to explain that he was a very influential ad patriotic gentleman, one of the most prominent in the neighborhood. Being a justice of the peace he is frequently called Squire Read, and, holding a commission under the Provincial Government we sometimes hear of him as Captain Read. In addition to his house we also read of Brown's Fort. To aid further explanation I submit a map embracing the entire district.

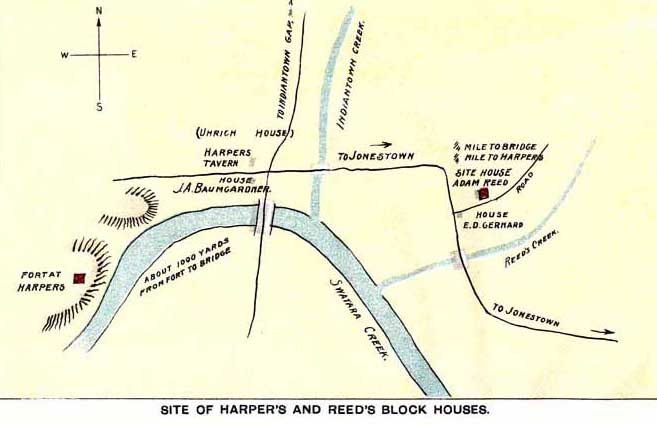

(Site of Harper's and Reed's Block Houses.)

It will be noticed that the Swatara creek, which takes a southwesterly direction after leaving Swatara Gap, suddenly tends to the northwest until once more near the mountain when, at the village now called Harper's, it makes a sharp turn around and then pursues its regular southwesterly course to the Susquehanna river. About one and one-fourth miles southeast from Harper's creek, called "Read's creek," empties into the Swatara. On a road running off from the main road to Jonestown, and one-fourth mile above where the latter crosses Read's creek by a bridge, stood Adam Read's house, on property now owned by Samuel Reigel. This location is fixed by Mr. C. D. Zehring, an old gentleman residing at Jonestown, who has made frequent surveys thereabouts and obtained the information from old deeds and papers in his possession. It is corroborated by his brother John, now 79 years old, who lived the greater part of his life on Read's creek, and further proven by Mr. Read himself who, in speaking of the murder of Noah Frederick, states that it took place between his home and Fort Swatara "but two short miles" from the latter and "a little better than two" from the former. In other words his home was exactly four miles from Fort Swatara, which agrees precisely with its position as marked. (Col. Rec., vii, p. 303.)

About two miles distant from Harper's and one and a half miles south of the village of Mt. Nebo, on the Swatara creek, are still found caves which local tradition unites in saying were used by the settlers as places of refuge from the Indians. It was shown, by Mr. J. A. Baumgardner, at Harper's, the site of what he called an Indian fort. He remembers very distinctly hearing the old people talk about this fort when he was a boy, some 40 years ago. The sketch given will indicate its position.

Here, at the bend in the Swatara, Mr. Adam Harper settled himself at an early period. His location was the most western in the county at that time. He was surrounded by Indians, who had a string of wigwams hard by his home. He kept the first public house in all that region of country. The place is still known at "Harper's Tavern," and stood as shown. Not half a mile distant from this place, in 1756 the Indians killed five or six white persons. A woman - a sister of Major Leidig - was scalped by the Indians, and, incredible, as it may appear, survived this barbarous act and lived for years afterwards. (Rupp, p. 353.)

Of course the so-called fort at Harper's was not, strictly speaking, a fort, but merely a place of refuge. It is very probably that it was connected in some way, with the Indian massacre mentioned above.

We are now prepared to discuss the remaining defense of those centering about Manada and called Brown's Fort.

BROWN'S FORT.

So little is known of this fort, and what little is known is of such an indefinite character, that it has been variously placed in different counties if placed at all. In the Appendix to the Pennsylvania Archives, p. 346, it is said that "there is nothing to determine the site of this fort (if indeed there was a fort of that name), and the other one not far from it; as the letter (Adam Read's) is dated Hanover it was probably either in Beaver or Washington county." Whilst it is true that there is but little on record concerning Brown's Fort, yet a statement such as the above is certainly inexcusable. Our chief knowledge of this fort is obtained from the letter written by Squire Adam Read to Edward Shippen, already given in full, wherein he details the shooting of the soldiers. (Penn. Arch., ii, p. 738.) It is dated "Hanover, August 7th, 1756." His residence, just located, stood in what has always been called Hanover Township of Lebanon (then Lancaster) county, from this time to the present. What more natural then, in the absence of our present villages and postoffices, than that he should head his communication "Hanover," and what more unnatural than to locate the said Hanover in Beaver or Washington county. Indeed the postoffices to this day are called East and West Hanover. I believe if we consider his letter carefully, which does not seem to have been done in the past as it should, we may get some light on the matter. Let us do so:

A soldier, named Jacob Ellis, belonging to Capt. Smith's command, was stationed at Brown's Fort. We will here remember that whilst Capt. Smith himself was at Fort Swatara, his headquarters, yet a commissioned officer and certain number of men from his company, and under his command, were stationed at and near Manada Gap. This man Ellis "lived two and one-half miles over the first mountain, just within the gap at said fort." So we find that Brown's Fort was near the gap, and we know that it was Manada Gap from a letter written August 9th by James Galbraith to Edward Shippen in which he says, speaking of this very affair "there were two soldiers killed and one wounded about two miles from Monaday [Manada] fort." (Penn. Arch., ii, p. 740.) He had some wheat growing at his home and wanted to harvest it, so accordingly prevailed upon his officer to give him an escort of ten men to aid in the work. Anyone who has made a study of this portion of our history will readily see that an important part of the soldiers duty was guarding the settlers at their work whilst harvesting their crops. For that purpose they were divided into small parties which were stationed at various suitable farm houses. The time of harvest was now at hand, and the mere fact that so little mention is made of Brown's Fort is evidence in itself that it was no fort at all, strictly speaking, but merely a private house temporarily occupied by a squad of soldiers. I say a "squad" of soldiers because, in all such cases, the number was limited. If that were so, and it certainly was, then there was no commissioned officer with then, and yet we read that he obtained the necessary permission from his officer, a lieutenant, who gave him so considerable an escort that undoubtedly a part were furnished from his headquarters, which was Manada Fort. This would indicate that Brown's Fort was at no great distance from Manada Fort. Indeed I was somewhat inclined to believe, at first, that they were one and the same place, but undoubted information received, to be given later, showed me such was not the case. To continue our narrative, the soldiers went up into the gap, where Ellis lived, and got to work, keeping a poor look out. About ten o'clock A.M., they were surprised by three Indians, who killed the corporal and wounded another. For awhile there was quite a scene of excitement when finally the Indians fled, giving a war whoop and firing a farewell shot. Having hid the dead man the other soldiers returned to the fort only to find another of their number missing, one named James Brown, who lived in the fort. We are then told that the Lieutenant immediately went out with more men and brought in the dead body but could not find Brown. Here we have several facts mentioned, one that the fort was, as I have already said only a private house, the residence of a man named Brown, although not necessarily James Brown, who may have been merely a son or relative living there, but still of some person so called or the fort would not have been recorded as Brown's Fort; and the other fact suggested is that Brown's Fort and Manada Fort were near each other and easy of access, because during a comparatively short time in the afternoon, the Lieutenant is informed of the calamity, takes a body of men to the spot, spends some time in searching for the missing man, and brings back the dead body, all before evening, which he could hardly have done had the distances been otherwise that short. As will be shown on the map given, the position of Brown's Fort was really but one and three-fourths miles east of Manada Fort, and, in going from the former to the Gap and back, it was almost necessary to pass by the latter. Mr. Read adds that he heard shooting that night. These were probably alarm guns, which may have been fired at Brown's Fort to alarm the people, or even by some of the farmers themselves. Although the location to be given presently of Brown's Fort places it near the mountains and about five miles distant from Mr. Read's house, yet the reverberating sound of fire arms near the mountain, in a still night, could have been heard at that distance without much difficulty. During my tour of investigation I several times heard guns so fired which, although several miles off, seemed very loud and near; even the stroke of a wood chopper's axe, a mile distant, was very distinctly heard. I doubt, however, whether he could so readily have heard a musket if fired at Manada Fort. The next morning, he tells us, he went up with some hands, to ascertain the cause of the alarm and render assistance, if needed. Upon arrival he found Capt. Smith had sent up more men from "the other fort." Please note the words which are placed in quotation marks. It has been a query as to which is meant by the "other fort." Let us not forget that Capt. Smith had his headquarters at Fort Swatara, where he probably was. Of course that same evening the lieutenant, if he was any kind of an officer, sent notice to his captain of what had occurred. The distance from Fort Swatara to Brown's Fort was about nine miles, and what more natural than that Capt. Smith should send some temporary reinforcements "up" from Fort Swatara," the other fort," where he was, not knowing but what the Indians were in force and that more troops would be needed. Finding that his kindly meant assistance was unnecessary Mr. Read returned home, but the following morning went back, when he found that the body of James Brown had been discovered. He was killed by the last shot which the Indians had fired, and had been scalped.

Let us now consult the map given.

I cannot think otherwise but that a glance at this location of Brown's Fort will show how thoroughly it corresponds and agrees with all records we have of it. It stood on the main road between Fort Swatara, Manada Fort and Manada Gap. Being merely a farm house, intended to be occupied only during harvest time, it was well situated for that purpose, being adjacent to quite a number of farms. As corroborating evidence of the correctness of my arguments I would say that diligent search reveals the fact that the Browns then lived in that locality. There were several families of that name, none of them apparently of any prominence, but all residing thereabouts. I found none of that name elsewhere. Within this century, some 80 years ago, a Samuel Brown lived just south of Manada Furnace; Philip Brown lived about one-half mile north of Grantville on what is now the farm of Daniel Ulrich, and Adam Brown, who died some 60 years ago, lived on the farm now owned by Amos Walmer. On the map will also be noticed an old stone house, standing about one mile north of Shellsville, which is the original building then occupied by John Crawford, (where it will be remembered Maj. James Burd stopped overnight on Sunday, February 19, 1758, when on his tour of inspection,) who instead of fleeing away from his enemies, as did others, took especial pleasure in hunting them up and despoiling them of their scalps. All the elderly people in the neighborhood agreed in saying that the building which I have marked, on the property of Mr. Jno. L. Ramler, was an Indian Fort. They did not know it by the name of Brown's Fort, but called it the "Old Fort." This, however, is not to be wondered at, as Brown's Fort was never really its name, but merely the name of its occupant used by Mr. Read the better to describe it in his letter. Mr. Ramler, who lives at the place, whilst but a young man himself, remembers very distinctly of his grandfather, who died four years ago at the age of eighty-three, telling him that his place was a fort, and that there was another fort at or near Manada Gap. Whilst, as yet, I have not had opportunity to trace the ownership of this particular property back beyond our century and so ascertain if, at the time named, it was owned by a Mr. Brown, yet I have no doubt of that fact, and the universal opinion of Mr. Ramler and other gentlemen there is that this is Brown's Fort. As a further proof of this they say positively that no other fort (except Manada) existed anywhere about that locality. Part of the walls of the building are still standing, about six feet high, alongside the road. It was of stone, therefore well adapted for the purpose, and was pierced with five port holes. It is close to the foot of the mountain.

As elsewhere, many atrocities were committed by the savages in the vicinity of Manada Gap.

In August, 1757, two miles below the Gap, as Thomas McGuire's son was bringing some cows out of a field, a little way from the house, he was pursued by two Indians and narrowly escaped. Leonard Long's son, while ploughing, was killed and scalped. On the other side of the fence, Leonard Miller's son was ploughing, who was made prisoner. Near Benjamin Clark's house, four miles from the mill, two savages surprised Isaac Williams' wife and the widow Williams, killed and scalped the former in sight of the house, she having run a little way after three balls had been shot through her body. The latter they carried away captive. (History of Penn., W. H. Egle, vol. ii, p. 865.)

The following interesting incident is related by Dr. Egle in is History of Dauphin County, p. 424: "The Barnetts and immediate neighbors erected a block house in proximity to Col. Green's Mills (Robinson's, now Early's Mill on land of Timothy Green) on the Manada, for the better safety of their wives and children, while they cultivated their farms in groups, one or two standing as sentinels. In the year 1757, there was at work on the farm of Mr. Barnett a small group, one of which was an estimable man name Mackey. News came with flying speed that their wives and children were all murdered at the block house by the Indians. Preparations were made immediately to repair to the scene of horror. While Mr. Barnett with all possible haste was getting ready his horse, he requested Mackey to examine his rifle to see that it was in order. Everything right they all mounted their horses, rifle in hand, and galloped off, taking a near way to the blockhouse. A party of Indians lying in ambush rose and fired at Mr. Barnett, who was foremost, and broke his right arm. His rifle dropped; an Indian snatched it up and shot Mr. Mackey through the heart. He fell dead at their feet, and one secured his scalp. Mr. Barnett's father, who was in the rear of his company, turned back, but was pursued by the Indians, and narrowly escaped with his life. In the meantime Mr. Barnett's noble and high-spirited horse, which the Indians greatly wished to possess, carried him swiftly out of the enemy's reach, but, becoming weak and faint from the loss of blood, he fell to the ground and lay for a considerable time unable to rise. At length, by a great effort, he crept to a buckwheat field, where he concealed himself until the Indians had retired from the immediate vicinity, and then, raising a signal, he was soon perceived by a neighbor, who, after hesitating from some time for fear of the Indians, came to his relief. Surgical aid was procured, and his broken arm bound up, but the anxiety of his mind respecting his family was a heavy burden which agonized his soul, and not until the next day did he hear that they were safe, with the exception of his eldest son, then eight or nine year of age, whom the Indians had taken prisoner, together with a son of Mackey's about the same age. The savages on learning that one of their captives was a son of Mackey, whom they had just killed, compelled him to stretch his father's scalp, and this heart-rending, soul-sickening office he was obliged to perform in sight of the mangled body of his father.

The Indians escaped with the two boys westward, and, for a time, Mackey's son carried his father's scalp, which he would often stroke with his little hand and say, "my father's pretty hair."

Mr. Barnett lay languishing on a sick bed, his case doubtful for a length of time, but, having a strong constitution, he, at last, through the blessing of God, revived, losing about four inches of a bone near the elbow of his right arm.

But who can tell the intense feeling of bitterness which filled the mind and absorbed the thoughts of him and his tender, sensitive, companion, their beloved child traversing the wilderness, a prisoner with a savage people, exposed to cold and hunger, and subject to their wanton cruelty? Who can tell of their sleepless nights, the anxious days, prolonged through long, weary months and years; their fervent prayers, their bitter tears, and enfeebled health?

The prospect of a treaty with the Indians, with the return of prisoners, at length brought a gleam of joy to the stricken hearts of these parents. Accordingly, Mr. Barnett left his family behind and set off with Col. Croghan and a body of five hundred "regulars" who were destined to Fort Pitt for that purpose. Their baggage and provisions conveyed on pack horses, they made their way over the mountains with the greatest difficulty. When they arrived at their place of destination, Col. Croghan made strict inquiry concerning the fate of the little captives. After much fruitless search, he was informed that a squaw, who had lost a son, had adopted the son of Mr. Barnett and was very unwilling to part with him, and he, believing his father had been killed by the Indians, had become reconciled to his fate, and was much attached to his Indian mother.

Mr. Barnett remained with the troops for some time without obtaining or even seeing his son. Fears began to be entertained at Fort Pitt of starvation. Surrounded by multitudes of savages, there seemed little prospect of relief, and, to add to the despondency, a scouting party returned with the distressing news that the expected provisions, which were on the way to their relief, were taken by the Indians. They almost despaired - 500 men in a picket fort on the wild banks of the Allegheny river without provisions. The thought was dreadful. They became reduced to one milch cow each day, for five days, killed and divided among the 500. The three following days they had nothing. To their great joy on the evening of the third provisions arrived. Every sunken, pale, despairing countenance gathered brightness, but, owing to its imprudent use, which the officers could not prevent, many died.

While the treaty was pending many were killed by the Indians, who were continually prowling around the fort. One day Mr. Barnett wished a drink of water from Grant's Spring (this spring is near Grant street, in the city of Pittsburgh, known to most of the older inhabitants); he took his "camp kettle" and proceeded a few steps, when he suddenly thought the adventure might cost him his life, and turned back; immediately he heard the report of a rifle, and, looking towards the spring, he saw the smoke of the same, - the unerring aim of an Indian had deprived a soldier of life. They bore away his scalp, and his body was deposited on the bank of the Allegheny.

The treaty was concluded and ratified by the parties; nevertheless great caution was necessary on the part of the whites, knowing the treachery of many of their foes.

Mr. Barnett was most unhappy. His hopes concerning his child had not been realized, and he had been absent from his family already too long. Soon after the conclusion of the treaty a guard, with pack horses, started to cross the mountains, and he gladly embraced the opportunity of a safe return. After injunctions laid upon Col. Croghan to purchase, if possible, his son, he bade him, and his associates in hardships, farewell, and, after a toilsome journey, reached home and embraced, once more, his family, who were joyful at his return. But the vacancy occasioned by the absence of one of its members still remained. He told them that William was alive, soothed their grief, wiped away the tears from the cheeks of his wife, and expressed a prayerful hope that, through the interposition of a kind Providence, he would eventually be restored to them.

Faithful to his promise, Col. Croghan used every endeavor to obtain him. At length, through the instrumentality of traders, he was successful. He was brought to Fort Pitt, and for want of an opportunity to send him to his father, was retained under strict guard, so great was his inclination to return to savage life. On one occasion he sprang down the bank of the Allegheny river, jumped into a canoe, and was midway in the stream before he was observed. He was quickly pursued, but reached the opposite shore, raised the Indian whoop, and hid himself among the bushes. After several hours' pursuit he was retaken and brought back to the fort. Soon after, an opportunity offering, he was sent to Carlisle. His father, having business at that place, arrived after dark on the same day, and, without knowing, took lodging at the same public house where his son was, and who had been some time in bed. As soon as he was aware of the fact he asked eagerly to see him. The landlord entreated him to let the boy rest till morning, as he was much wearied by traveling. To this the father would not assent, replying, "If a son of yours had been absent for three years could you rest under the same roof without seeing him?" The hardy host felt the appeal and led the way to the chamber. The sleeping boy was awakened and told that his father stood by his bed. He replied in broken English, "No my father." At this moment his father spoke, saying, "William, my son, look at me; I am your father!" On hearing his voice and seeing his face he sprang from the bed, clasped him in his arms, and shouted, "My father! My father is still alive!" All the spectators shed tears, the father wept like a child, while from his lips flowed thankful expressions of gratitude, to the Almighty disposer of all events, that his long lost child was again restored.

Early the next day the father and son were on the road homewards, where they arrived on the second day in the dusk of the evening. The rattling of the wheels announced their approach; the mother and all the children came forth. She, whose frequent prayers had heretofore been addressed to the Throne of Divine Grace for the safety and return of her son, now trembled and was almost overcome as she beheld him led by his father and presented to her, the partner of her sorrows. She caught him to her bosom and held him long in her embrace, while tears of joy flowed. His brothers and sisters clustered eagerly around and welcomed him with a kiss of affection. It was a scene of deep feeling not to be described, and known only to those who have been in similar circumstances. The happy family, all once more beneath the parental roof, knelt down and united in thanksgiving to Almighty God for all His mercies to them in protecting and restoring to their arms a beloved and long absent child.

The children scrutinized him with curiosity and amazement. Dressed in Indian costume, composed of a breech-cloth around the waist, with moccasins, and leggings, his hair about three inches long and standing erect, he presented a strange appearance. Be degrees he laid aside the dress of the wilderness and became reconciled to his native home. But the rude treatment which he received from the Indians impaired his constitution. They frequently broke holes in the ice on rivers and creeks and dipped him in to make him hardy, which his feeble system could not endure without injury.

Respecting the son of Mackey, he was given by the Indians to the French, passed into the hands of the English, and was taken to England, and came as a soldier in the British army to America at the time of the Revolutionary war. He procured a furlough from his officers and sought out his widowed mother, who was still living, and who had long mourned him as dead. She could not recognize him after the lapse of so many years. He stood before her, a robust, fine-looking man, in whom she could see no familiar traces of her lost boy. He called her "mother," and told her he was her son, which she could not believe. "If you are my son," she said, "you have a mark upon your knee that I will know." His knee was exposed to her view, and she instantly exclaimed, "My son indeed!" Half frantic with joy, she threw her arms around his neck, and was clasped in those of her son. "Oh, my son," said she, "I thought you were dead, but God has preserved you and given me this happiness. Thanks, thanks to His name! Through long years I have mourned that sorrowful day which bereft me of my husband and child. I have wept in secret till grief has nearly consumed me, till my heart grew sick and my poor brain almost crazed by the remembrance. I have become old more through sorrow than years, but I have endeavored to 'kiss the rod' which chastised me. My afflictions have not been sent in vain, they have had their subduing and purifying effect; heaven became more attractive as earth became dark and desolate. But I now feel that I shall yet see earthly happiness. Nothing in this world, my son, shall separate us but death." He never returned to the British army, but remained with his mother and contributed to her support in her declining years.

There was another interesting meeting, that of Mackey with the son of Mr. Barnett. They recapitulated the scenes of hardship through which they passed while together with the Indians, which were indelibly impressed upon the memory of both. They presented a great contrast in appearance - Barnett a pale, delicate man, and Mackey the reverse. The former sank into an early grave, leaving a wife and daughter. The daughter married a Mr. Franks, who subsequently removed to the city of New York.

Mr. Barnett, the elder, after experiencing a great sorrow in the loss of his wife, removed to Allegheny county, spending his remaining days with a widowed daughter. He died in November, 1808, aged 82 years, trusting in the merits of a Divine Providence. His eventful and checkered life was a life of faith, always praying for a sanctified use of his trials, which were many. His dust reposes in the little churchyard of Lebanon, Mifflin township, Allegheny county."

Of all the places used for defense about Manada none seem to have played a prominent part in history, yet all served faithfully in the several parts assigned to them. Only one of these, Manada Fort, belonged to the chain of forts established by the Government. If only such are to be marked with tablets, I would recommend that the stone intended for it be placed on the side of the public road, opposite the site.

______

Previous Page People Name Index Next Page