REPORT OF THE COMMISSION TO LOCATE THE SITE OF THE FRONTIER FORTS OF PENNSYLVANIA.

VOLUME ONE.

CLARENCE M. BUSCH.

STATE PRINTER OF PENNSYLVANIA.

1896.

The Frontier Forts Within The Wyoming Valley Region.

By Sheldon Reynolds, M. A.,

President of the Wyoming Historical and Geological Society.

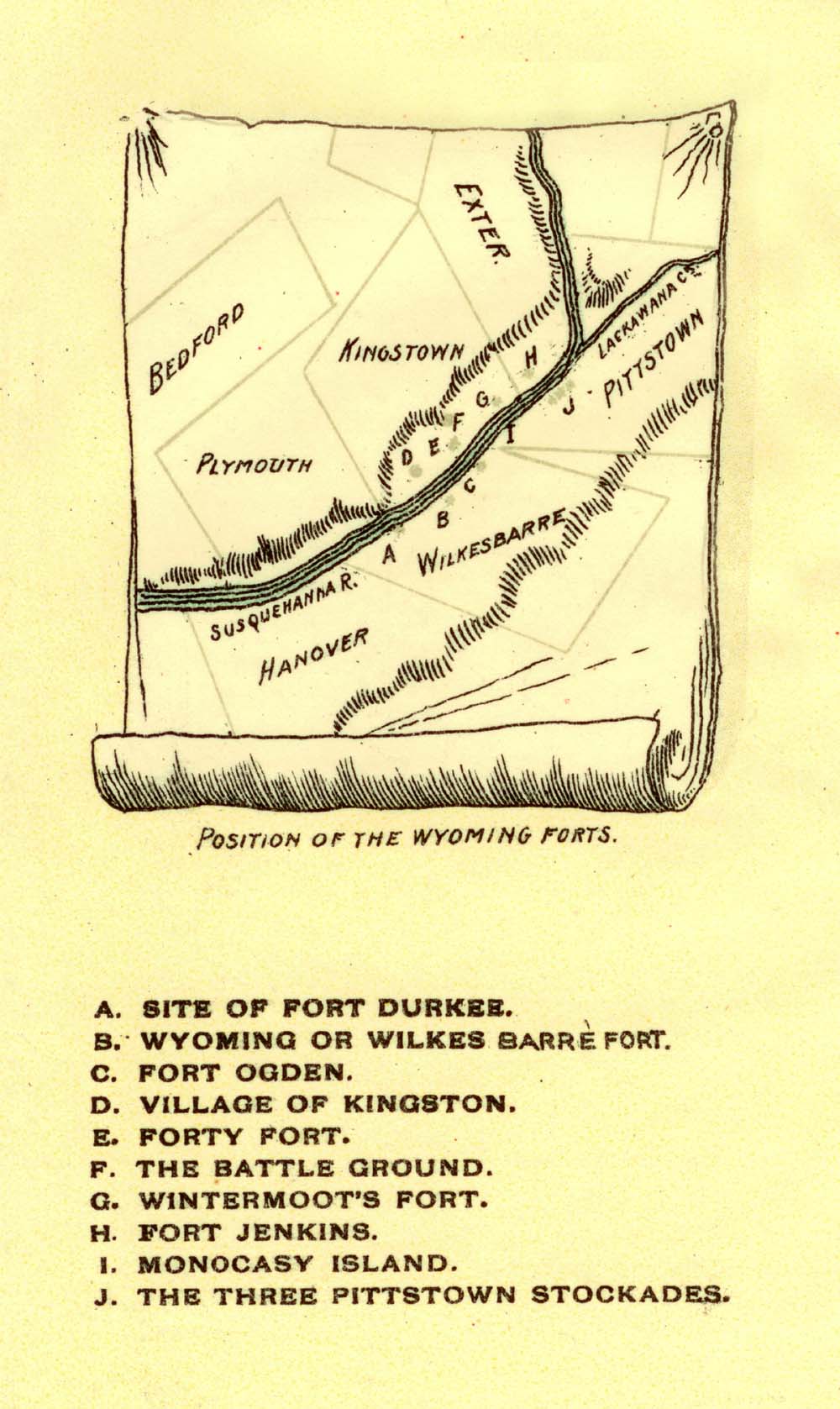

Illustration of Position of the Wyoming Forts.

IN MEMORIAM.

Pages 421-422.The article following this introductory note was written by Mr. Sheldon Reynolds during a long illness which ended in his death at Saranac Lake, N. Y., on the 8th of February, 1895. It was dictated in part by him to his brother, Col. G. M. Reynolds, and was finished almost with the life of its author. To those whose privilege it was to know Mr. Reynolds, his story of the troubled times of the last century is fraught with peculiar and almost painful interest. The manful and heroic effort he made to end his task against the heavy odds of his physical weakness and fast advancing disease, and his final accomplishment of his labors, were most characteristic of his spirit and tenacity of purpose. How well the work was done the article speaks for itself, and no one could know from its perusal that the hand which wrote it could at the last scarce clasp a pen, and that the calm and judicial tone which pervades the account of the early trials and hardships of our forefathers was the expression of one whose life was fast ebbing away and who felt himself urged by the most pressing necessity to complete a work which he knew too well to delay at all would be to leave unended.

Mr. Reynolds was of New England stock, his ancestors, coming from Litchfield, Conn., were among the first of the original settlers in the Wyoming Valley, and one of the name laid down his life in defense of his home and kindred with the many other heroes whose blood stained the fair fields of the valley on the fatal third of July, 1778.

Mr. Reynolds was a graduate of Yale University in the class of 1867. After his graduation he was called to the bar and for a short time practiced law. His mind was eminently judicial and logical, and had he cared for fame as a lawyer he had all the equipment of careful training and natural aptitude which would soon have brought him distinguished success in his profession.

But his tastes lay not in this direction. The study of history and archaeology fascinated him and he especially delighted in the elucidation of the local traditions and history with which this region overflows. To fit himself for this form of study, he trained his mind in the most rigid and exacting school of modern historical research, and followed the foremost examples of critical methods in this branch of literature; and now, when all these years of careful preparation were passed and the field he had labored in was ripe for fruitage, he was taken from us and we have left but the memory of his patient, zealous work, the benefit and charm of which have been denied us except in the few short articles which came from his pen.

His was a noble character, full of love for truth, winning and lovable. Companionable in the highest degree to the intimate few who knew that beyond the reserve and quiet pose of manner lay a spirit full of life and enthusiasm, a mind stored with a fund of knowledge and general information, and that an hour spent in his company was sure to bring one both pleasure and profit. Only those who knew him thus can appreciate to its full meaning the loss to a community of a citizen with such broad aims, noble impulses and unselfish desire and willingness to labor for the advancement of every worthy enterprise; and only those who knew him thus can understand how deep-seated is the sadness and the personal bereavement that comes to one whose years of comradeship with him had cemented a friendship that only death could break.

______

FRONTIER FORTS IN THE WYOMING VALLEY.

Pages 423-425.Forts erected prior to 1783 as a defence against the Indians within the territory bounded east by the Delaware river, south by the forty-first degree north latitude, on the north by the State line and west by the extreme western boundary of Luzerne county and a line drawn thence at an equal distance west of the Susquehanna river to the New York State line. (The authorities consulted in the preparation of this article are Chapman's, Miner's, Peck's and Stone's Histories of Wyoming; Pearce's Annals of Luzerne County, Proceedings and Collections of Wyoming Historical and Geological society, Matthew's History of Wayne, Pike and Monroe Counties, and Pennsylvania Archives. The writer acknowledges his indebtedness to Hon. C. I. A. Chapman and Hon. James M. Slocum.)

The territory inclosed within these boundaries comprises a large part of that municipal division known in early times as the town and county of Westmoreland, then under the political jurisdiction of Connecticut. It will be remembered that by the words of the Connecticut charter her western boundary was the "South Sea," and in pursuance of her right thus stated in her charter, the colony made claim to lands lying between the forty-first and forty-second parallels of latitude west of the Delaware river. Of these claims the one that was urged with most vigor and persistence, and resisted with equal resolution, was made on behalf of the Susquehanna Company, for the lands on the Susquehanna, bought of the Indians of the Six Nations, at Albany, in 1754. This purchase included the lands of Wyoming on the Susquehanna, and was the first step on the part of the Connecticut people and their associates, members of the Susquehanna Company, towards the settlement of Wyoming. Actual settlement of the region was not undertaken, however, until 1762. In the following year an end was put to the undertaking by an attack made upon the settlement by the Indians living in the neighborhood and the massacre of about twenty of the settlers. Further attempts were given up until the year 1769, when the first permanent settlement was made. Prior to this event these conflicting claims had been the subject of argument and negotiation: but with strong representatives of each party upon the ground and thus brought face to face—as between them—arguments ceased, and a resort to force was adopted, although under the guise of civil process. These methods were quickly followed by acts of violence, and civil authority was lost sight of amid the sound of arms and the exciting incidents of open warfare.

The late Governor Hoyt, in his able review of these claims in his "Syllabus of the Controversy between Connecticut and Pennsylvania," says:

"Some years ago, in the course of professional employment, I had occasion to arrange some data embraced in the following brief. They consisted mainly of charters, deeds and dates and were intended for professional use. They were too meagre for the present purpose. They should embrace a wider range of facts, their relations and appropriate deductions from them. The controversy herein attempted to be set forth, one hundred years ago was raging with great fierceness, evoked strong partisanship, and was urged, on both sides, by the highest skill of statesmen and lawyers. In its origin it was a controversy over the political jurisdiction and right of soil in a tract of country containing more than five millions of acres of land, claimed by Pennsylvania and Connecticut, as embraced, respectively, in their charter grants. It involved the lives of hundreds, was the ruin of thousands, and cost the State millions. It wore out one entire generation. It was righteously settled in the end. We can now afford to look at it without bias or bitter feeling."

This controversy was an event in the history of Wyoming which cast its baneful influences over every activity that contributed to the progress and growth of the settlement; it affected the inhabitants in all their material relations. Any successes achieved by them were wrought out despite of it, and their failures and misfortunes were of a character more disheartening and lasting by reason of this ever present menace.

It was thought proper to thus briefly mention this controversy arising out of these conflicting claims, owing to its great and continuing influence upon the settlement, as well as its intimate relation to the history of several of the forts, which served at intervals, both as a defence against the Indians and as a means of enforcing the claims of the several parties.

______

FORT DURKEE AND OTHER DEFENCES.

Pages 425-437.In April, 1769, soon after their arrival in the disputed territory, the Connecticut people set about the building of a fort for their better protection. They chose a site now within the limits of the city of Wilkes-Barre, on the river bank between the present streets, South and Ross. Here they built of hewn logs a strong block house surrounded by a rampart and intrenchment. It was protected on two sides by natural barriers, having on one side the Susquehanna river, and on the other, the southwest, side, a morass with a brook flowing through it and emptying into the river near by the fort at a place called Fish's Eddy. The size of the enclosure is not known, but it was probably of one-half an acre in extent, as any place of shelter in time of danger of less space would be of little use. The fort was looked upon as a strong military defence, both from its manner of construction and the natural advantages of its position. Near to it were built also twenty or more log houses, each provided with loop holes through which to deliver the fire in case of a sudden attack. It was named Fort Durkee in honor of Capt. John Durkee, one of the leaders of the Yankee forces, and who had seen service in the late war with France, and afterwards, as a colonel of the Connecticut line on the continental establishment, served with merit throughout the Revolutionary war. While this fort was erected as a defence against the Indians, and doubtless served that purpose, there is no evidence that it ever sustained an attack from that quarter. It was, however, one of the strong-holds that played a very important part in the contest with the Proprietary government over the disputed jurisdiction and title to the Wyoming lands, known as the first Pennamite war, beginning in 1769 and continuing two years. Shortly after this period the name of the fort disappears from the records; whether it was dismantled or suffered to fall into decay is not known. Miner's history of Wyoming, page 265, makes a last reference to it in these words: "The whole army (Gen. Sullivan's) was encamped on the river flats below Wilkes-Barre, a portion of them occupying old Fort Durkee." (June 23, 1779.) If the fort was at that time in a condition to serve any useful purpose, it is difficult to understand why the people of the town were at such pains to build in 1776 a fort for their protection on the Public Square, inasmuch as Durkee was a much stronger place and quite as convenient, or how a work of this importance escaped destruction at the hands of the enemy after the battle of Wyoming. The brook mentioned above as forming one of the safeguards of the fort, has long since disappeared. One branch of it had its rise near the place known as the Five Points, and the other branch in the Court house square; the latter flowed in a southerly direction, emptying into a marsh at a point near the Lehigh Valley railroad. The stream leaving the marsh crossed Main Street near Wood street, and took a northerly course to Academy and River streets, where it was spanned by a bridge, thence it flowed into the river at Fish's Eddy. There has been some question in respect to the location of this fort. The principal evidence in favor of the site as stated is twofold: the land on the southwest side of the stream and morass was low land, subject to overflow upon every considerable rise of the river, and therefore of a nature wholly unsuited for a work of the kind. Hon. Charles Miner, whose recollection of events happening prior to the beginning of this century was clear, says in effect, that Durkee was located sixty rods southwest of Fort Wyoming, and that the remains of the latter fort were in a tolerable state of preservation in the year 1800. (History of Wyoming, p. 126.) The site of the latter fort is well known and the distance of sixty rods in the direction indicated, fixes the location of Durkee as given above.

Fort Wyoming was located on the river common, about eight rods southwest of the junction of Northampton and River streets in the city of Wilkes-Barre. It was built in January, 1771, by Capt. Amos Ogden, the able leader of the Proprietary forces, and one hundred men under his command. The purpose of its erection was the reduction of Fort Durkee, the stronghold of the Yankees, and like Durkee it became an important factor in carrying forward to an issue the controversy alluded to. In 1771 it fell into the hands of the Connecticut people. It was not built, as is apparent from the statement just made, as a defence against the Indians; but seems to have been used for that purpose in 1772 and 1773 and later. It was this fort doubtless that is mentioned in the records of those years, as "the fort in Wilkes-Barre" where constant guard was required to be kept. After this time, it passes out of notice; no account has come down to us of the manner of its destruction or other disposition. It is reasonable to suppose that it was not standing in 1776, as the people would have made use of it instead of building a fort in that time of need. This fort gave its name to a successor built on the same site in 1778, and which became an important post during the period of the war.

Mill Creek Fort was situated on the river bank on the north side of the brook of the same name, which now forms the northern boundary line of the city of Wilkes-Barre. It was built in the year 1772, after the cessation of hostilities between the Connecticut settler and the Pennamite. It occupied the site of the Pennamite stronghold known as Ogden's Fort, named in honor of Capt. Ogden, which had been captured and burned in 1770. The position was a strong one, standing on the high bank of the river, protected on two sides by the river and the brook. It was designed to guard and control the mills upon that stream, as well as to furnish a safe retreat to the people of the neighborhood. The necessity of the times seems to have been pressing, for we are informed that the settlers in and about Wilkes-Barre moved into the fort the same year, taking their household goods and other personal effects along with them. Huts were erected along the inner walls of the fort which provided sufficient room for all who came. The community continued to occupy the fort as a dwelling place for a considerable period, and until the alarm, from whatever source it came, had subsided. This place was the scene of the first settlement by the Connecticut people, as well as of the tragedy of 1763. The improvements, consisting of a log house and a few small cabins, were erected here. Upon the return of the settlers in the year 1769, they made their way thither in hopes of finding a place of shelter and defence. The improvements, however, had fallen into the hands of the Pennamites who were secured in a strongly fortified block house, known as Ogden's Fort, and prepared to resist any steps looking to a settlement. This historic spot is now covered in part by a culm heap of the Lehigh Valley Coal company. The tracks of the Lehigh Valley railroad cross it in one direction, while a bridge of the Wilkes-Barre and Eastern spans it in another. The pumping station and mains of the Wilkes-Barre Water company and the mains of an oil pipe line complete the occupation.

The Redoubt was the name given to a rocky spur that projected at right angles across the river common from the main hill about ten rods above Union street. Its precipitous sides reached nearly to the edge of the river bank. Standing some seventy feet above the water it was a prominent land-mark, and an advantageous position in the local military operations. On the occasion of the siege of Fort Wyoming in 1771 a gun was mounted here by the Yankees; and though no execution seems to have been done, the practice was doubtless of benefit Again, in 1784, during the second Pennamite war, a like use was made of this eminence by the Connecticut people. They took possession of the Redoubt, which lay between the fort and the grist mills on Mill creek that were also in the hands of the Pennamites, and thereby cut off the supplies of the fort; all the houses standing between the fort and the Redoubt were burned so that there might be no obstruction to the fire directed upon the garrison. Other uses were doubtless made of this strong position in time of need, though no account of them has been recorded. A tradition that there was a guard stationed there with a mounted gun to defend the passage of the river, the writer has been unable to verify; but it is so probable that there seems little doubt of its truth. It will be remembered that the river was the one highway north and south, and the Indians of the Six Nations made use of it on many occasions to reach the vicinity of Wyoming. After the year 1778, in most of their raids upon Wyoming and the settlements along the Blue Mountains, the savages were borne as far south as Wyoming upon the river floods. Any body of men occupying the Redoubt could effectually prevent the passage of this point by canoes, and compel the invading party to leave the river and make a wide detour in order to reach their destination. However well the Redoubt was situated for the uses mentioned, its location in respect to the march of modern improvements was quite unfortunate; it seems to have been planted directly in its path. The North Branch canal, by a sweeping turn at this point, sheared off two of the rocky faces of the barrier. The extension of River street cut a deep channel through it in another direction, severing it from the main hill. The Lehigh Valley railroad, successor to the canal, to obtain room for its tracks, took off another portion; and the city deported the remainder, bringing it to the level of the rest of the common and down to the city grade. The name, however, has always adhered to it, and although no vestige of the eminence remains, the "Redoubt" is a familiar name that still marks the spot.

Nothing can be found showing that these several fortifications were ever subject to attack in any warfare with the Indians; though they undoubtedly fall within the sense of the designation "forts erected as a defence against the Indians, etc." In the years 1772 and 1773 a general feeling of alarm and apprehension pervaded the Wyoming settlement; the people lived in forts; they went about their daily work with arms in their hands; they strictly enforced the law in respect to military duty, and required guard mount in each township. This condition of affairs was probably owing to two causes. The isolated and exposed position of the settlement made it liable to attack and at the same time deprived it of the hope of assistance from any quarter. The warlike Six Nations were their neighbors on the north, and, although they professed to be friendly, the knowledge of their treacherous character and the recollection of the massacre in 1763, the act of Indians claiming to be friendly, were still fresh in the minds of the settlers. Secondly, the likelihood of a renewal of the hostilities with the Proprietary government was nowise remote; the withdrawal of their men from the disputed territory since August, 1771, held out no assurance of future inactivity. The settlers were liable to attacks from either source without warning, and they made the best disposition of the means at hand for their protection. At a meeting of the proprietors in November, 1772, it was ordered that every man who holds a settling right shall provide himself with a good firelock and ammunition according to the laws of Connecticut, "by the first Monday of December next, and then to appear complete in arms at ye fort, in Wilkes-Barre, at twelve o clock on said day for drilling as ye law directs." It was further provided that each township shall elect a muster officer and inspector and they shall choose two sergeants and a clerk. The inhabitants shall meet every fourteen days armed and equipped, and in case of alarms or appearance of an enemy, they shall stand for the defence of the town without further orders. In October, 1772, it was ordered "that every man of the settlers shall do their duty both for guarding and scouting or lose their settling right." The requirement of keeping guard night and day in the fortified places applied to all the townships, under the penalty, in case of failure or neglect, of losing their settling rights; it was in force in 1772 and 1773, and probably longer. At this time also a stockade was built in Plymouth, the location of which is not now known, a block house was erected in Hanover, and the fort in Kingston, known as Forty-Fort was put in a state of repair. In addition to these nearly every dwelling house was loop-holed and made a place of defence. A community so well prepared and alert probably escaped an open attack solely by reason of their readiness to repel it; and the forts that never sustained an assault owed their immunity to the same cause.

The town of Westmoreland was established by Act of the Connecticut Legislature in 1774; it comprised the territory lying between the forty-first and forty-second degrees north latitude, the Delaware river and a line fifteen miles west of the Susquehanna river. (Miner, page 158.) In 1776 the same authority erected the county of Westmoreland with boundaries coincident with the town of the same name. With the exception of a few small settlements on the Delaware river, Wyoming was the only inhabited portion of the town of Westmoreland. Wyoming was the name of an Indian village, situated within the present limits of the city of Wilkes-Barre, and was inhabited at the time of the first attempt by the Connecticut people to effect a settlement of the place in 1762. This name was applied to the lands of the Susquehanna Company's purchase of 1754; and at a later period was used in a more restricted application and designated what were known as the settling townships and a few adjoining them. The settling townships were those assigned to the earliest settlers, and were named WilkesBarre, Hanover, Plymouth, Kingston and Pittston; these, together with Exeter and Newport townships, which were surveyed soon after the others, comprised all the land within the Wyoming Valley. The establishment of the town of Westmoreland produced among the settlers a feeling of security, and a belief that the powerful aid and protection of the mother colony would now be extended to Wyoming. Much progress had already been made in the arduous work of establishing the settlements, notwithstanding the warfare that had been waged for nearly three years, and the season of alarms and anxiety that followed. This official act gave a new impetus to the undertaking and added nerve and energy to the efforts of the workers upon the ground. In the few years that intervened between the time of their arrival and the battle of Wyoming in 1778, when the settlement was cut off, the Connecticut settler had established in this distant wilderness a vigorous, orderly and prosperous colony. Townships were surveyed in accordance with uniform methods of a carefully ordered land office, and the lands allotted to those entitled to them. Highways were laid out and improved; the land much of it a wilderness, was brought under a state of cultivation and productiveness; courts of justice were established and law and order prevailed; school houses were built in the several districts and free schools opened; provision was made for the preaching of the gospel, and for the support of the ministry and the schools three shares in each township were set aside, amounting to about one thousand acres of land. It must be admitted that this herein barely outlined undertaking was of vast proportions and beset by many difficulties, and its accomplishment in so brief a time and under such adverse circumstances speaks highly of the character, resolution and perseverance of the people who wrought it out. The dispute between the colonies and the mother country had already reached open rupture, Lexington and Bunker Hill possessed a deeper significance for these people than for others. It aroused their patriotism and united them in the cause of the colonies; but it carried with it, moreover, a menace that filled them with the most serious apprehensions. No one knew better than they the temper and disposition of the Six Nations on their northern border. A war with Great Britain meant an invasion of their homes by a savage enemy. The upper boundary of Westmoreland reached beyond the southern limit of the Indian country, and included several of the Indian towns. Among these was Tioga Point, at the junction of the Tioga branch with the Susquehanna; it was an important place and served as a rendezvous for the savages by reason of its accessibility from numerous towns and villages, and later became a base of attack upon Wyoming. Many of their paths and trails likewise lay within the boundaries of Westmoreland. They were near neighbors therefore; and from their southernmost towns could readily reach the heart of Wyoming during any rise in the river, within twenty-four hours, by simply floating in their canoes with the river's current. In case of attack their approach was likely to be silent and swift and under cover of the night. Furthermore, Wyoming was an outpost whose isolation was complete. The distance to the nearest settlement on the Delaware was seventy miles, and a wilderness, traversed by a few trails only, intervened. Sunbury was her nearest neighbor on the south, and was at an equal distance. In the face of these conditions the following quoted resolutions meant to these settlers something more than the simple expression of their adherence to the cause.

"At a meeting of ye proprietors and settlers of ye town of Westmoreland, legally warned and held in Westmoreland, August 1st, 1775, Mr. John Jenkins was chosen Moderator for ye work of ye day. Voted that this town does now vote that they will strictly observe and follow ye rules and regulations of ye Honorable Continental Congress, now sitting at Philadelphia.""Resolved by this town, that they are willing to make any accommodations with ye Pennsylvania party that shall conduce to the best good of ye whole, not infringing on the property of any person, and come in common cause of Liberty in ye defence of America, and that we will amicably give them ye offer of joining in ye proposal as soon as may be." The meeting adjourned to August 8th, and then "Voted as this town has but of late been incorporated and invested with the privileges of the law, both civil and military, and now in a capacity of acting in conjunction with our neighboring towns within this and other colonies, in opposing ye late measures adopted by Parliament to enslave America. Also this town having taken into consideration the late plan adopted by Parliament of enforcing their several oppressive and unconstitutional acts, of depriving us of our property, and of binding us in all cases without exception whether we consent or not, is considered by us highly injurious to American or English freedom; therefore do consent to and acquiesce in the late proceedings and advice of the Continental Congress, and do rejoice that those measures are adopted, and so universally received throughout the Continent; and in conformity to the Eleventh article of association, we do now appoint a Committee to attentively observe the conduct of all persons within this town, touching the rules and regulations prescribed by the Honorable Continental Congress, and will unanimously join our brethren in America in the common cause of defending our liberty."

Many incidents in the following winter and spring confirmed the fears of the settlers touching the disposition of the Six Nations toward them; the Indians living near the settlements became insolent in their behavior; some of them departed from the Valley and others, believed to be spies, took their places; hostile acts were committed by them in the neighborhood of Wyoming, the responsibility for which they not only denied, but on the other hand urged complaints against the settlers. The menace thus grew until its imminent character led the people to apply for aid to the colony of Connecticut, knowing themselves to be unable to withstand so powerful an enemy. Failing in their appeal to the mother colony, the circumstances of their case were laid before the Congress. In the meantime they took their condition under their own consideration at a town meeting, and adopted such measures as lay within their power to provide for the safety of the several settlements within the town of Westmoreland.

The town meeting referred to was "legally warned and held in Westmoreland, Wilkes-Barre district, August ye 24th, 1776. Col. Butler was chosen moderator for ye work of ye day.

"Voted, it is the opinion of this meeting that it now becomes necessary for ye inhabitants of this town to erect suitable fort or forts, as a defence against our common enemy."

"August 28th, 1776, this meeting is opened and held by adjournment."

"Voted, ye three field officers of ye regiment of this town be appointed as a committee to view the most suitable places for building forts for ye defence of said town, and determine on some particular spot or place or places in each district for the purpose, and mark out the same."

"Voted, that the above-said committee do recommend it to the people in each part as shall be set off by them to belong to any fort, to proceed forthwith in building said fort, etc., without either fee or reward from ye said town."

The committee, under the powers given to it by the above vote, began its labors by a study of the needs of each township; and the most advantageous sites for works of defence were carefully examined. In some of the townships there were stockades or fortified places, erected at the time of the early settlement a few years before, though since then suffered to fall into decay. These, wherever it was deemed to be practicable, were ordered to be put in a good state of repair, and the best posture of defence of which the circumstances would admit. Forty-Fort in Kingston township, and Pittston Fort in the township of the same name, two of the most important locations, as events proved, were accordingly enlarged and strengthened. In other townships where there were no forts in such a state of repair as to be useful in the present emergency, suitable sites were chosen by the committee and the proposed works marked upon the ground. Sites were fixed upon in Wilkes-Barre, Plymouth and Exeter for the building of forts, and for blockhouses in lower Pittston and Hanover.

The regiment, the three field officers of which were a committee to locate the forts, was the Twenty-fourth regiment of Connecticut militia created soon after the establishment of the town of Westmoreland, nominally for the defence of the town. Inasmuch as the officers were residents, and the men enlisted from among the inhabitants of the place, and were required to arm and equip themselves, it cannot be claimed that this organization added much if anything, to the military strength of a community wherein every man had been accustomed to arm himself and do military duty whenever and as long as circumstances required. It was made up of nine companies; but it is doubtful if the number of men was equal to half the usual number of a company. The recruiting of other companies, especially the two Independent Companies, thereafter mentioned took from the ranks of the regiment a large number of its best men. It was six of the nine companies of this regiment, together with a few raw recruits, that fought the battle of Wyoming, and at that time the roster of these companies showed a strength of about two hundred and thirty men. The strength of the whole regiment was probably less than three hundred and fifty. In answer to the appeal for aid, Congress on the 23d August, 1776, "Resolved, that two companies on the Continental establishment, be raised in the town of Westmoreland, and stationed in proper places for the defence of the inhabitants of said town, and parts adjacent, till further orders of Congress; the commissioned officers of said two companies, to be immediately appointed by Congress."

"That the pay of the men, to be raised as aforesaid, commence when they are armed and mustered, and that they be liable to serve in any part of the United States, when ordered by Congress."

The commissioned officers were duly appointed by Congress, and in less than sixty days the companies were recruited to the number of eighty-four men each. They were known as the "two Independent Companies of Westmoreland." The promise and expectation that these companies should be stationed in "proper places for the defence of the inhabitants" of Westmoreland were quickly defeated by the overwhelming necessity that confronted Congress. The battle of White Plains was fought October 25th, 1775, followed by the retreat of Washington; other disasters occurred in quick succession. Philadelphia was threatened by the enemy and December 12th, Congress resolved to adjourn to Baltimore. On the same day they ordered the two Independent Companies of Westmoreland "to join Gen. Washington with all possible expedition." The consequences of this action on the people of Wyoming are so obvious that they scarcely need recounting; the chief strength of the community was taken away; the burdens of their situation were more than doubled, and the dangers that surrounded them were increased. In the same degree that this action was disastrous to Wyoming, was it of advantage and encouragement to its enemies. It furnished new motives for an invasion and removed many of the difficulties surrounding such an undertaking. Congress was acquainted with the defenceless condition of Wyoming and the dangers that threatened her; and was well aware what evils were likely to befall the settlement in consequence of the removal of these troops. The motives that prompted this action on the part of Congress and her refusal to allow the companies to return even when the destruction of Wyoming seemed certain, has been a subject of much speculation. It seems clear, however, that in the mind of Congress the probable cutting off of this frontier settlement was an affair of less consequence than the possible weakening of the army by detaching even two companies in the face of the enemy. It was a question of policy into which no sentiments of justice and humanity seem to have entered. In connection with this subject it may be proper to refer to the number of men supplied by Wyoming to the army. In the summer of 1776 Captain Wisner enlisted twenty or more men for the Continental service, and about ten men were enlisted by a Captain Strong. Immediately afterward the one hundred and sixty-eight men of the "two Independent Companies of Westmoreland" were likewise mustered, as has been stated, making about two hundred men in the service. In Miner's History of Wyoming, page 206, the number of these troops is reckoned in 1777—reduced by a year's hard service—at one hundred and sixty. The quota of Connecticut is there estimated at two thousand one hundred and fifty men; the quota of Wyoming would have been twenty-one men. Allowing her only one hundred and sixty men in the service, she therefore sent to ‘the war nearly eight times her just number. But as has been well said, in the situation that prevailed at Wyoming, "every man might justly be regarded as on duty continually. Every man might have been considered as enlisted for and during the whole war. There was no peace, no security at Wyoming." (Memorial to Congress, Wyoming Sutterers, etc. Miner, App. 78. )

Deprived of most of her able-bodied men in the manner above shown, the usual labors of the farm, sowing and harvesting necessary for ‘the sustenance of the people, the guard mount day and night and the continuous duty of scouting called for the strenuous exertions of all: and the arduous undertaking of building the several forts, decided upon by the committee of the field officers of the regiment, could not be carried forward with the despatch the circumstances demanded. Still, such progress was made as the discharge of the many other duties permitted. Some of the forts were finished in the following summer, 1777, others were suffered to wait for another year. All, however, were completed in time to serve the purposes of their erection; and before July, 1778, were ready for their garrisons. Some of the garrisons, as in Plymouth, Wilkes-Barre and perhaps other forts, were composed of the aged men, exempt by law from duty; others were of the militia of the Twenty-fourth regiment, as in Forty-Fort and Pittston.______

FORTY FORT.

Pages 438-443.

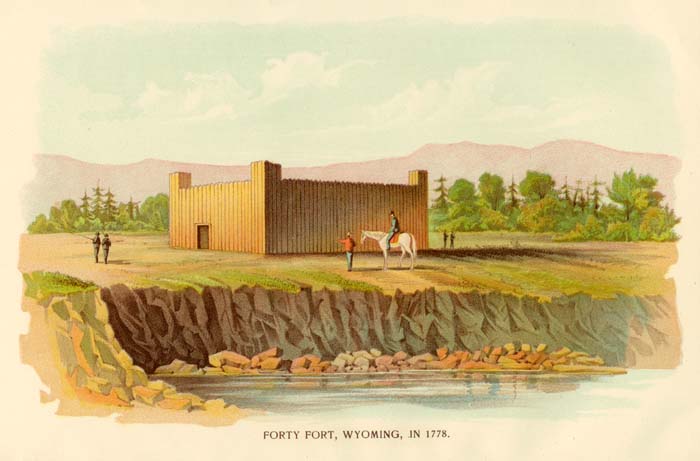

Forty Fort, Wyoming, in 1778.

The site of this stronghold is in the borough of the same name on the southerly side of the line of the junction of River street with Fort street. Standing on the high western bank it was admirably situated to command the river at this point. It derived its name from the forty pioneers who, having been sent forward from Connecticut in 1769 by the Susquehanna Company to take possession of the land in its behalf, were rewarded for their services by a grant of the township of Kingston, and from this circumstance known likewise as the township of the Forty, and the Forty town, within which the fort was located. The building of the fort was begun In the year 1770, and served as a place of security in time of danger and alarm; at a later period it seems to have been partly destroyed, or at least left in a condition not fitted for guarding as the law of the time required, for we learn that in 1772 and 1773 the Kingston men were ordered to mount guard in the fort at Wilkes-Barre until they shall build fortifications of their own. (Westmoreland Records.) In 1777, under direction of the committee it was partly rebuilt, adding much to its strength, as well as its dimensions. Opinions differ as to its size, the better authority seems to be that it enclosed an acre or more of ground; indeed, recent excavations disclosed the remains of the timbers in place, extending in one direction two hundred and twenty feet, indicating in connection with other circumstances an inclosure of at least an acre. The walls of this fort were of logs, the material generally used in such defences; these were set upright in a trench five feet in depth, extending twelve feet above the surface of the ground, and were sharpened at the tops. The joints or crevices between the upright logs were protected by another tier of logs planted and secured in like manner, thus forming a double wall. Barracks or huts were built along the walls within the fort for the shelter of the occupants; the roof of these buildings serving as a platform from which the garrison could defend the works; and the space in the centre, surrounded by the barracks, was used as a parade. The inclosure was rectangular in shape, having a gateway opening towards the north, another towards the south, and small sentry towers at the four corners rising a few feet above the walls. A strong flowing spring at the margin of the river, below the structure, supplied water to the fort; access to the spring was rendered safe by means of a sunken passageway, having the top protected by timber work, leading down from the fort. A water supply was always one of the controlling influences in the location of a work of this character. This was true in the case of the several forts in Wyoming; some contained within their walls running water, others had springs near at hand in the present instance.

During the last days of June, 1778, when it became known that the enemy in great force was approaching Wyoming, the inhabitants generally sought the protection afforded by the several forts. Probably the largest number gathered at Forty-Fort, owing to its larger dimensions and promise of greater security. The militia likewise mustered at this point, marching from their several stations when the alarm was given, having first detached a few of their number to add the garrisons of the other forts.

Meantime the enemy, numbering about eleven hundred men, under command of Major John Butler, (Hist. Address, by Steuben Jenkins, Miner's Hist., Wyoming, p. 217.) had descended to the Susquehanna river in boats and landed a few miles above Wyoming. The enemy's forces were made up of two hundred British Provincials, and a like number of Tories, and about seven hundred Indians, chiefly Senecas and Cayugas. From the point of landing they marched by a route at a distance from the river and reached their destination on the night of July 1st, and camped on the mountain near the head of the Valley, four miles north of Forty-Fort. After having gained some small successes in the capture of two stockaded forts they sent a flag, July 2d, to Forty-Fort, demanding the surrender of the several forts in the Valley together with Continental stores. This demand was refused, and preparations were made to attack the enemy. Every available man was assembled at the fort, and the chief command given by common consent to Col. Zebulon Butler, a Continental officer at home on furlough. The force gathered at Forty-Fort numbered less than four hundred, made up of six companies of militia, the train bands, and old men and boys, "chiefly the undisciplined, the youthful, and the aged, spared by inefficiency from the distant ranks of the Republic." Scouts reported the enemy driving off cattle, plundering in the vicinity and preparing to leave the Valley. Of the number of the enemy they could give no information; it was, however, believed to be much smaller than in fact it was. These circumstances perhaps precipitated the battle. Deceived both in the number and purpose of the enemy, our men marched on the afternoon of July 3, 1778, to engage them in battle. After a march of three miles they formed in line of battle, presenting a front of some five hundred yards: in this order they advanced toward the enemy over ground covered with scrub-oaks and pitch pine, not high enough to obstruct the vision, but well adapted to form a cover for the Indians. The right of our line resting on a hill not far from the river was commanded by Col. Butler supported by Major John Garrett; the left stretching toward a marsh to the northwest, was under command of Col. Denison and Lieut. Col. Dorrance. The enemy s left wing, composed of British Provincials, was commanded by Major John Butler; next to them, and forming the centre were the Tories under Captains Pawling and Hopkins, on the right were the Indians. The enemy's right rested upon a marsh, and behind the thick foliage of its undergrowth there lay concealed a large number of Indian warriors. At the word of command our men advanced and delivered a rapid fire with steadiness, which was returned by the enemy who slowly fell back before our advancing column. Advancing thus for the distance of a mile our line found themselves in a cleared space of several acres where, unprotected by any undergrowth, they were exposed to galling fire from the British who were shielded by a kind of breastwork formed in part by a log fence running across the upper part of the clearing. The advance was checked, and at this moment the horde of Indians rushed from the swamp and in overwhelming numbers, with war whoop and brandishing of spears, fell upon our left, attacking it in flank and rear. Confusion ensued, orders were misunderstood or could not be executed. The left wing was forced back toward the right, the column was broken, and the day lost. Lieut. Col. Dorrance fell mortally wounded, Major John Garrett was killed; "every captain fell at his position in the line, and there the men lay like sheaves of wheat after the harvesters." In the flight from the field the men began moving off in squads firing at their pursuers, until decimated by fire and borne down by numbers, they fled as best they might. Some reached Forty-Fort, others fled to the river, and a few of these succeeded in crossing and reaching Wilkes-Barre. Those who were taken were either killed outright or reserved for death by torture the following evening. Our loss is variously estimated at from one hundred and sixty to two hundred. Major John Butler, the commander of the enemy, says two hundred and twenty-seven scalps were taken. The loss of the enemy is unknown, but it is believed to have been from forty to eighty. Such was the battle of Wyoming, very briefly and imperfectly told.

Col. Denison escaped from the field and assumed command at Forty-Fort. On the following day, the 4th of July, a second demand was made by the enemy for its surrender. There was no means at hand for further resistance, and the terms offered being looked upon as favorable as could be expected under the circumstances, the fort was given up in accordance with the following articles:

Westmoreland, July 4, 1778.

"Capitulation made and completed between Major John Butler, on behalf of His Majesty King George the Third, and Col. Nathan Denison, of the United States of America.Art. 1. That the inhabitants of the settlement lay down their arms and the garrisons be demolished.

2d. That the inhabitants are to occupy their farms peaceably and the lives of the inhabitants preserved entire and unhurt.

3d. That the Continental stores be delivered up.

4th. That Major Butler will use his utmost influence that the private property of the inhabitants shall be preserved entire to them.

5th. That the prisoners in Forty-Fort be delivered up, and that Samuel Finch, now in Major Butler's possession, be delivered up also.

6th. That the property taken from the people called Tories, up the river, be made good: and they to remain in peaceable possession of their farms, unmolested in a free trade, in and throughout this State, as far as lies in my power.

7th. That the inhabitants, that Col. Denison now capitulates for, together with himself, do not take up arms during the present contest."

These articles having been duly executed the fort was immediately surrendered.

The victorious columns of the enemy were seen marching toward the fort. On the left were the British Provincials and Tories in columns of four, led by Major Butler; on the right were their painted savage allies, disposed in like order. With banners flying, to the music of the fife and drum, and with all the pomp and circumstance of war which so heterogeneous a mass could assume, they approached the fort. At a signal the gates were thrown open. Butler and his followers marched in by the north gate, while the Indians, led by their chiefs, entered by the south gate. All the arms of the fort, stacked in the centre of the parade, were given up to Major Butler who at once presented them to the savages, saying "they were a present from the Yankees," and then turning to Col. Denison, remarked, "That as Wyoming was a frontier, it was wrong for any part of the inhabitants to leave their own settlements and enter into the Continental army abroad; that such a number having done so, was the cause of the invasion, and that it would never have been attempted if the men had remained at home." Col. Franklin, who heard the declaration, added, "I was of the same opinion."

The people had taken with them into the fort many of their household goods and personal belongings; these now became a prey to the cupidity of the savages, who, unrestrained by any authority, went about the fort robbing the inmates of whatever they possessed, even to the clothes they wore. From robbing the people in the fort they soon passed to the plunder and devastation of the whole valley, burning and destroying wherever they went. Many of the people living in Wilkes-Barre and the settlements below Forty-Fort, had already begun their flight through the wilderness toward the Delaware, and to Sunbury by the way of the river. The flight now became general and continued in terror and panic until nearly all had gone. A few remained in their cabins in the forts for a fortnight or more, detained by illness or by the lack of means of getting away.

Notwithstanding the terms of the capitulation this fort was not demolished, and a few years afterwards was put in repair and garrisoned for a short time.

WINTERMOOT S FORT.

Pages 443-445.Wintermoot's Fort was situated in Exeter township, between Wyoming avenue, in the present borough of Sturmerville, and the Susquehanna, about eighty rods from the river. It consisted of a stockade surrounding a dwelling house, and was built prior to the time of holding the town meeting, August, 1776, by the Wintermoots, a numerous family who had lived in that neighborhood for some time. They had fallen under the suspicion of their neighbors by reason of various circumstances, which led to the belief that the family were Tories and in communication with the enemy. The building of the fort had not been sanctioned by any one in authority and this circumstance deepened the distrust with which they were looked upon; though no facts were at hand that might confirm the suspicions or serve as grounds to support charges against them. This state of affairs, however, was enough to put the inhabitants on their guard, and led to the action of the town meeting of August, 1776, which required that all forts should be located by the committee, in order that thereafter, no one who was under suspicion should be permitted to build a fort. The fort was under command of Lieut. Elisha Scovell; and at the approach of the enemy it sheltered a few families of the neighborhood. At the command to surrender a feeble show of resistance was made, but all serious efforts of defence were opposed by the Wintermoots who said that Major Butler, the commander of the enemy, would find a welcome there. (Miner, 218.)

On the evening of July 1, the enemy encamped on the mountain nearly opposite this fort and within two miles of it. Parties of the enemy passed in and out of the fort during the night; the next morning the gates were thrown open and possession given up. It is probable that the enemy here learned the number and disposition of our forces; our defensive works, locations and the quantity of plunder that would fall to the lot of his savage ally. This fort became the headquarters of Major Butler. The capitulation was made on the following terms:

"Wintermoot's Fort, July 1, 1778.

"Art. 1st. That Lieut. Elisha Scovell surrender the fort, with all the stores, arms and ammunition that are in said fort, as well public as private, to Major John Butler.2d. That the garrison shall not bear arms during the present contest, and Major Butler promises the men, women and children shall not be hurt, either by Indians or rangers."

On the 3d of July at about the time our troops were forming their line of battle, the fort was set on fire and consumed. No motive has been assigned for the act; whether it was by design or accident is not known. It seems probable that Major Butler studied to have it appear that the Wintermoots were looked upon by him as belonging to our side; it might be of service to them in the future. This view would account for the unnecessary formality of articles of capitulation in the surrender of their fort and also for its destruction. The Wintermoots joined the enemy and in their company withdrew from the Valley a few days later, (Stone's History, Wyoming, 201.) and received the reward due them for their treachery. Col. Zebulon Butler, in his report of the battle refers to this fort in the following words: "In the meantime (July 1-3) the enemy had got possession of two forts, one of which we had reason to believe was designed for them, though they burnt both." All the authorities concur in the belief that the Wintermoots were in secret communication with the enemy, and that the fort was built with the ultimate purpose of giving it up to them and to aid and abet their cause.

______

JENKINS FORT.

Pages 445-446.This site was fixed by the committee before mentioned under resolution of the town meeting of August, 1776; and the building was begun soon after that date. Being in the neighborhood of Wintermoot's Fort it was looked upon as a counter-check to that structure—and this may have been the reason it was so speedily finished. It was situated in Exeter township, within the present limits of the borough of West Pittston, about ten or twelve rods northeast of the Pittston Ferry bridge. Standing upon the top of the high bank, and overlooking the river, the place was subject to the encroachment of the current. Through the lapse of years a large part of the bluff has been washed away, and a considerable part of the site is now the river's bed.

The structure was a stockade built around and in connection with the dwelling house of John Jenkins, hence its name. The stockade part was built in the usual manner by planting upright timbers in a trench of proper depth; these uprights were sharpened at the tops, and in this case, owing to their small size doubtless, "were fastened together by pins of wood and stiffened with two rows of timbers put on horizontally and pinned to the uprights inside, thus stiffening and uniting the whole into a substantial structure." Several families were gathered within this inclosure on the evening of July 1st for the protection it seemed to promise. Immediately after the surrender of Wintermoot's Fort a detachment of the enemy under command of Captain Caldwell of the Royal Greens was sent to reduce this place. The garrison consisted of but eight available men, and no effectual resistance being possible, surrendered the fort under the following terms:

Fort Jenkins Fort, July 1, 1778.

"Between Major John Butler, on behalf of his Majesty King George the Third, and John Jenkins.

"Art. 1st. That the fort with all the stores, arms and ammunition be delivered up immediately.

2d. That Major John Butler shall preserve to them, intire, the lives of the men, women and children."

Like Wintermoot's Fort, it was burned during the battle, two days later.

______