NATIVE AMERICAN RESEARCH

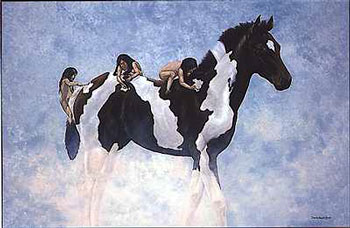

'When Little People Paint'

Searching for Native American Ancestors

A common tradition found in many American families is the one pertaining to an unknown Native American ancestor. Sometimes the legend can be documented, but often it cannot. Before you tackle tracing a Native American line, become familiar with genealogical research by doing some research on one of your other branches. This will prepare you for the rather complex records you will encounter in the search to ascertain whether you have any Indian blood.

Talk to all your relatives, and learn as much as possible about your Indian ancestors. If the name of the tribe is known (though it seldom is), you will be able to take a shortcut and go directly to the tribal records.

However, in most cases, the tribal affiliation will not be known, and it will be necessary to study the localities, especially the place of birth, where your Indian relatives have lived. Next research the Indian tribes that are known to have been located in those geographical areas and those tribes who now have reservations or live in those areas. This information will help you narrow down the tribal possibilities.

If the family story simply claims that your great- great-great-grandmother was part Cherokee (the most famous tribe), you must trace, generation by generation, the family line connected to her. Since few Native American records of genealogical value exist prior to 1830s, if your family legend places your Indian ancestor earlier than this, it may be impossible to prove the story. However, the research will be an adventure into the pages of American history.

Once you have determined the tribal affiliation, you can write to an office of the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) in the tribal area. Each branch of the BIA serves as a central depository for the records of the Indian tribes within its jurisdiction. These records consist of documents pertaining to tribal enrollment, allotment or land, probate, as well as others. The BIA can direct you to the proper repository of the records you are seeking.

Two other repositories have millions of records pertaining to Native Americans. They are the National Archives in Washington, D.C., and the Family History Library in Salt Lake City. Regional branches of the National Archives in Fort Worth, Chicago, Kansas City, Seattle, Denver, San Francisco, Los Angeles and Atlanta, also have myriad records pertaining to Native Americans who once lived in their regions. Many of these are available on microfilm. At any Family History Center check the library's catalog. Under the state where your families lived look for available microfilmed records under topics pertaining to Indians. Example: "Oklahoma/minorities," or "Kansas/native races." Also check under "United States/native races."

Names are a frequent problem encountered in this research. In the 1880s, when the annual federal Indian census lists began, you may find your ancestor listed under two different names — one being his Indian name, the other an English one. Word of caution: Indian census lists do not prove tribal affiliation — you must find the enrollment lists.

If your ancestors belonged to one of the Five Civilized Tribes — Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Creek or Seminole — read chapter 17 of "The Source: A Guidebook of American Genealogy," edited by Eakle and Cerny. "Cherokee Connections," by Myra Vanderpool Gormley, and is available from Family Historian Books, 404 Tule Lake Road, Tacoma, WA 98444 ($11.95 postpaid) focuses on researching ancestors of that renowned tribe.

An excellent book is "Guide to Records in the National Archives of the United States Relating to American Indians," compiled by archivist Edward E. Hill.

Locating a Native American ancestor who was not historically famous will make a super sleuth out of you. If your families have been in America more than a century, probably there is a family tradition that you have Indian blood. Verifying stories is what makes research fascinating.

One of the most recurring stories in American families is that one of your ancestors is an Indian maiden — usually a princess. Beware of accepting at face value any Anglo terms given to Native Americans. The second part of the tradition may be that the family was not necessarily proud of their mixed blood, and would not talk about it. There may or may not be any truth to such stories.

Examine carefully traditions that claim your Indian blood came through a female. While it is true that many of our mixed pedigrees are the result of a union (legal or not) of a white male and an Indian female, Indian men cohabitated with white females also.

You may have a female ancestor who was taken captive by what early historians called "savages" and carried off to an Indian village. These white women were usually taken as wives by tribesmen. And if you trace a branch of your family tree to such a union, it will take you into the real history of America. Accounts of captivity of white females are slanted. Use them for research, but don't accept as the complete story.

Tracking your Native American heritage is a difficult, time-consuming project, but you will never be bored.

There is an enormous amount of material available pertaining to our Indian ancestors. First determine what tribe they were from and then learn where and when they lived. Next determine what records, usually federal government ones, were generated that might pertain to them.

Most of our knowledge about American Indians is woefully shallow. A trip to a large public or university library is mandatory. Read everything you can find about the history of the tribe your family tradition claims descent from.

The University of Oklahoma Press publishes many books about American Indians, including the Civilization of the American Indian Series. You can obtain its most recent general catalog by requesting it from OU's Press, 1005 Asp Avenue, Norman, Okla. 73019.

You may discover that your Cherokee lines actually were Choctaw, Creek, Chickasaw, or Seminole or you may descend from Alabama-Coushatti ancestors who lived in Texas.

If your Indian ancestors ever received monies or land from the government, there is a good chance you will be able to document your Indian blood. The National Archives has a select catalog entitled American Indians. It provides information about the microfilm publications available for research. It's available ($2) from National Archives Trust Fund Board, Washington, D.C. 20408. Another outstanding guide to the American Indian records in the National Archives is American Indians, compiled by Edward E. Hill. It costs $15 and can be obtained from National Archives, P.O. Box 37066, Washington, D.C. 20013.

Every time there was a census or a head count the Native Americans learned that its nation and people lost something — land, wealth, or freedom. As a result many of them refused to report for enumerations. Thus some of your Indian ancestors may not appear on records until when the very last tribal roll was taken.

Those whose family legends pertain to Native American ancestors prior to the 1830s face sophisticated and difficult research. Sometimes these lineages can be proven. Often they can not, but the research will make a genealogist out of you, and you will learn a great deal of American history and Native American culture along the way.

This page is maintained for the USGenWeb Archive Project by Linda Simpson

©1998-2009 for the USGenWeb Project