The

Ashcraft Pioneers

Of Arkansas

ashcraft329@yahoo.com

The Arkansas Ashcrafts, along with several other families, migrated from the York/Chester County area of South Carolina to southern Arkansas between 1853 and 1860. News had traveled back to the Carolinas from Arkansas about the rich, virgin soil and the low-priced land in the area being offered for sale by the federal government. Being farmers, the Ashcrafts were attracted to the undulating, fertile earth of the present-day Cleveland County area. Between 1857 and 1861, eight descendants of Immigrant Thomas Ashcroft patented almost 1500 acres near Mt. Elba on the southeastern banks of Big Creek as it flows into the Saline River.

02

Apr 1859

Uriah Ashcraft 41 acres

Section 4

Township 11S, Range 9W

01

Jun 1859

Jonathan Alexander Ashcraft 80 acres

Section 21 Township 10S, Range 9W

02

Jul 1860

William Leroy Ashcraft

200 acres

Section 33

Township 10S, Range 9W

01

Oct 1860

James Leonard Ashcraft

200 acres Section 31-32

Township 10S, Range 9W

01

Apr 1861

William Leroy Ashcraft

40 acres Section 33

Township 10S, Range 9W

01

Apr 1861

Thomas Kelsey Ashcraft

120 acres Section 23

Township 10S, Range 9W

Brother-in-law to the above and first husband of Rebecca Ashcraft, Jackson Chambers, patented the following land parcels:

01

Jun 1859

Andrew Jackson Chambers

80 acres

Section 21 Township 10S, Range 9W

01

Oct 1860

Andrew Jackson Chambers

80 acres

Section 21 Township 10S, Range 9W

From South Carolina to Arkansas

1852

– 1860

John

Ashcraft and his second wife, Rebecca, moved their family from North Carolina

to the Fishing Creek area of South Carolina in 1799, following the birth of

their oldest son Joel. The boundary line between York and Chester judicial

districts divided the land on which they established their home.

John had two ‘plantations’ as referred to in his will – one in

the Chester district which he and Rebecca called home and one to the north in

the York district.

At

times, supplies were depleted, wild game became scarce and fishing was

unproductive. Under these circumstances the wagons remained stationary while

the hunters ventured further from the road to find game. And, occasionally, a

family would have to stop long enough to bury their dead or wait for a baby to

be born.

Nearing

their destination, the travelers crossed the Mississippi River at Memphis.

From there, they continued to Little Rock, traveling what was part of a

network of wagon roads that spread through Arkansas, once referred to as

“The Southwest Trail”. Crossing the White and Arkansas Rivers, the first

of the Ashcraft pioneers arrived in present-day Cleveland County, Arkansas

during the early months of 1853.

Sharon

Spielman Ashcraft

Wife

of 3rd Great-Grandson of Joel and Patsey Ashcraft

February

2007

Notes:

Most of the counties in South Carolina became judicial districts in

1800; in 1868 all of the existing districts once again became known as

counties.

In

the 1850s, the Wylies, McCulloughs, Byrds, and McElhenneys were close

neighbors of the Ashcrafts in the Chester district of South Carolina.

Joel

and Patsey’s daughter, Ruth, married William B. Isom sometime between 1850

and 1860 and left South Carolina by 1880. Martha, another daughter, is

believed to have married a David Mann and may have gone to Cleveland County,

Arkansas via Mississippi in the latter part of the 1860s.

The

time frame of the departures from South Carolina is based primarily on the

years and places of births recorded in census records. Historical articles

combined with imagination laid the groundwork for the reasons the Ashcrafts

left South Carolina. A

biographical sketch of Wm. L. Ashcraft gives the year 1853 as the time the

first Ashcrafts arrived in Arkansas.

Ashcraft

Land Patents

Cleveland

County, Arkansas

1857-1861

The following is the chronological order in which Jesse, the younger son of John and Rebecca Ashcraft, two of his sons, five of his nephews, and Jackson Chambers who married Jesse’s niece, Rebecca, patented land in Cleveland County, Arkansas:

1859

– 01 June Jesse

Ashcraft, son of John and Rebecca Ashcraft

Jonathan

Alexander Ashcraft, son of Joel and Patsey (Ferguson) Ashcraft

Andrew

Jackson Chambers, son-in-law of Joel and Patsey (Ferguson) Ashcraft

1860

– 02 April Uriah

Ashcraft, son of Joel and Patsey (Ferguson) Ashcraft

1860

– 02 July William

Leroy Ashcraft, son of Joel and Patsey (Ferguson) Ashcraft

Jesse

Ashcraft, son of John and Rebecca Ashcraft

James

Leon Ashcraft, son of Jesse and Sarah (McClellan) Ashcraft

Thomas

A. Ashcraft, son of Jesse and Sarah (McClellan) Ashcraft

1860

– 01 October

Thomas A. Ashcraft, son of

Jesse and Sarah (McClellan) Ashcraft

James

Leonard Ashcraft, son of Joel and Patsey (Ferguson) Ashcraft

Andrew

Jackson Chambers, son-in-law of Joel and Patsey (Ferguson) Ashcraft

1861

– 01 April William

Leroy Ashcraft, son of Joel and Patsey (Ferguson) Ashcraft

Thomas

Kelsey Ashcraft, son of Joel and Patsey (Ferguson) Ashcraft

Jesse

Ashcraft

Younger

brother of Joel Ashcraft

These are the land patents of Jesse Ashcraft and two of

his sons:

1859

– 01 June Jesse

Ashcraft

80 acres Section 18

Township 10S Range

9W

1860

– 02 July Jesse

Ashcraft

222 acres Section 18

Township 10S Range

9W

James Leon Ashcraft

120 acres

Section 18 Township 10S

Range 9W

Thomas

A. Ashcraft

160 acres Section 19

Township 10S Range

9W

1860

– 01 October

Thomas A. Ashcraft

160 acres Section

19 Township

10S Range 9W

FREEDMAN'S

BUREAU RECORDS (FIELD OFFICE RECORDS, MONTICELLO, ARKANSAS)

HURRICANE TOWNSHIP

|

|||||

|

SOLDIER'S NAME |

REGIMENT |

STATUS |

FAMILY MEMBER |

RELATION |

CHILDREN |

|

|

|||||

|

Ashcraft, James |

1st AR. |

Ser. |

Sarah Jane |

Wife |

3 |

|

Ashcraft, Jonathan |

3rd AR. |

Ser. |

Sarah |

Wife |

3 |

|

Ashcraft, Thomas |

3rd AR. |

Ser. |

Mary |

Wife |

2 |

|

Ashcraft, Thomas |

Crawfords |

Ser. |

Margaret |

Wife |

2 |

1. James is James Leon, son of

Jesse. James’ wife is Sarah Jane Byrd. James Leon died of disease in 1863 at a

prison camp near Little Rock, Arkansas.

2. Jonathan is Jonathan Alexander, son of Jesse’s brother,

Joel. Jonathan’s wife is Sarah Dorcus Isom. Jonathan was captured at Longview,

Arkansas in 1864, refused to take the Oath of Allegiance to the United States

government, and was imprisoned until a prisoner exchange occurred in 1865 just

prior to the official end of the war.

3. The 1st Thomas

Ashcraft is Thomas Kelsey, brother of Jonathan and son of Joel. His wife is Mary

C. Ferguson. Thomas enlisted with the Confederacy as 5th sergeant but

was reduced to ranks several months later. He took the Oath of Allegiance to the

United States government in 1864 and returned home to Bradley (now Cleveland)

County.

4. The 2nd Thomas Ashcraft is Thomas A., son of Jesse and brother of James Leon. His wife is Margaret A. Patrick. Thomas enlisted in the Confederate Army in 1862, was reported Absent Without Leave in August of 1863, and took the Union’s Oath of Allegiance in September of that year.

The

Demise of My Great-Great-Grandfather

Morten Ashcraft

Artist unknown.

The drawing above shows a keelboat much like the one John “Morten” Ashcraft was on when he drowned in the swollen Saline River sometime between 1852 and 1860. His body was found three weeks later in a floating drift of river debris. The reason he was aboard the keelboat is not known, but as hard as people had to work in that era, it was probably not for pleasure

Keelboats were used on area rivers and large streams to transport items for sale or trade. Originally, the keelboats were designed to travel downstream only. They were dismantled after reaching their destination, the wood was sold, and the boats’ handlers walked back home. Neither practical nor economically feasible, dismantling soon gave way to the use of long poles to the river bottom and towlines from the shore to navigate the boats back upstream. Hides, flour, meal, salt, cotton and barrel staves were taken south; cane syrup, sugar, coffee, and lead were brought back upstream.

(Note: Nancy, born 1848, and Rebecca, born 1852, may have been half sisters; no mother is shown on the 1850 census.)

- Norman V. Ashcraft, December 2006

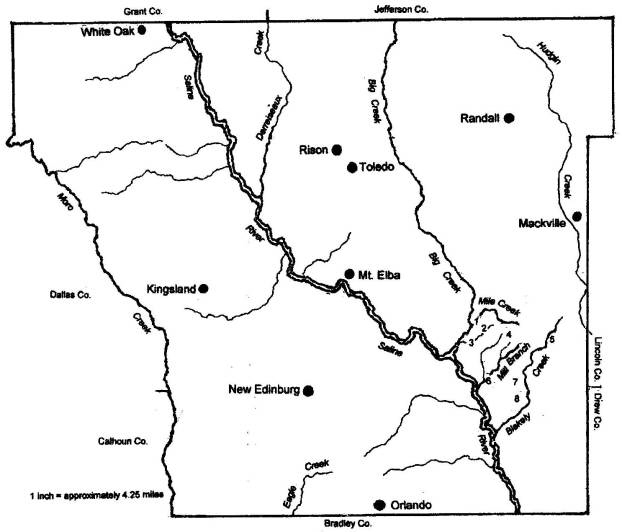

Map of Present-Day

The

area where the descendants

The towns shown on the map above have been indicated in order to

determine the location of the land the Ashcraft pioneers settled. Most of the

towns were non-existent in the mid-1850s. Two exceptions are Mount Elba and New

Edinburg; they were known as settlements as early as 1834 and 1835 respectively.

The lands the Ashcrafts patented are indicated numerically on the map

east of the Saline River to the southeast of Mount Elba. The numbers show the

location where each individual lived. They are as follows:

1.

Jesse Ashcraft

2. James Leon Ashcraft 3.

Thomas A. Ashcraft

4. Jonathan Ashcraft

5. Thomas K. Ashcraft

6. Jms. Leonard Ashcraft

7. William L. Ashcraft

8. Uriah Ashcraft